Abstract

On June 17, 2016, the Canadian government legalized medical assistance in dying (MAID) across the country by giving Royal Assent to Bill C-14. This Act made amendments to the Criminal Code and other Acts relating to MAID, allowing physicians and nurse practitioners to offer clinician-administered and self-administered MAID in conjunction with pharmacists being able to dispense the necessary medications. The eligibility criteria for MAID indicates that the individual 1) must be a recipient of publicly funded health services in Canada, 2) be at least 18 years of age, 3) be capable of health-related decision-making, and 4) has a grievous and irremediable medical condition.

Because this is a new practice in Canadian health care, there are no published Canadian statistics on MAID cases to date, and this paper constitutes the first analysis of MAID cases in both the province of Ontario and Canada. Internationally, there are only a few jurisdictions with similar legislation already in place (US, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Columbia, Japan, and the United Kingdom). The published statistics on MAID cases from these jurisdictions were reviewed and used to establish the current global practices and demographics of MAID and will provide useful comparisons for Canada.

This analysis will 1) outline the Canadian legislative approach to MAID, 2) provide an understanding of which patient populations in Ontario are using MAID and under what circumstances, and 3) determine if patterns exist between the internationally published MAID patient demographics and the Canadian MAID data.

Selected patient demographics of the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario were reviewed and analyzed using anonymized data obtained from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario so that an insight into the provision of MAID in Ontario could be obtained. Demographic factors such as age, sex, the primary medical diagnosis that prompted the request for MAID, the patient rationale for making a MAID request, the place where MAID was administered, the nature of MAID drug regimen used, and the status/specialty of medical personnel who administered the MAID drug regimen were analyzed.

The analysis revealed that the majority of the first 100 MAID recipients were older adults (only 5.2% of patients were aged 35-54 years, with no younger adults between ages 18-34 years) who were afflicted with cancer (64%) and had opted for clinician-administered MAID (99%) that had been delivered in either a hospital (38.8%) or private residence (44.9%).

Although the cohort was small, these Ontario MAID demographics reflect similar observations as those published internationally, but further analysis of both larger and annual case uptake in both Ontario and Canada will be conducted as the number of cases increases.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Medical assistance in dying, Medical aid in dying, Bill C-14, Euthansia, Suicide, Voluntary suicide, Legal methods of suicide

Introduction

Medical assistance in dying (MAID) is becoming more accessible for those who seek legal medical intervention to end their lives. Although ethically and legally controversial, it provides more end-of-life options using either clinician-administered or self-administered MAID. This paper will examine the newly introduced Canadian approach to MAID and the patient demographics of the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario since the Royal Assent and amendments of Bill C-14, while offering insight into MAID practices on a global scale.

Canadian Legislation

Bill C-14

Bill C-14 is the federal legislation that received Royal Assent on June 17, 2016, which ultimately legalized MAID across Canada and now provides more choices to Canadians in end-of-life decision-making. This act made amendments to the Criminal Code, which is the federal statute that contains the majority of criminal offences created by Canadian Parliament, and amendments were also made to other acts relating to MAID (1). This allows Canadian physicians and nurse practitioners (who are defined as clinicians in this area of practice) to offer clinician-administered and self-administered MAID in conjunction with pharmacists being able to dispense the necessary medications (1). The eligibility criteria for MAID indicates that the individual 1) must be a recipient of publicly funded health services in Canada, 2) be at least 18 years of age, 3) be capable of health-related decision-making, and 4) has a grievous and irremediable medical condition (1, 2). A grievous and irremediable medical condition is defined as a serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability, including decreased capability that is advanced and irreversible, intolerable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved, and natural death has become reasonably foreseeable (1, 2).

The individual must first make a voluntary request for MAID that is without external pressure and give consent to receive MAID after being informed of all the possible methods of relief from suffering, such as palliative care (1, 2). When there is objection by a clinician to provide MAID, the clinician must communicate this personal objection to the patient and make an effective referral to a clinician willing to assist the patient in a timely manner (2, 3). The process requires a written request that is signed and dated by the person or proxy and a copy of the physician's medical opinion stating that the individual has a grievous and irremediable medical condition (1, 2). Two independent witnesses must also sign and date the form. These independent witnesses must be at least 18 years of age, understand the request, must not be beneficiaries, must not own or operate the health care facility at which the patient is attending, and must not provide direct health care or personal care to the patient (1–3). In addition, the requesting patient must be informed of withdrawal opportunities at any time, and there must be an independent clinician to provide a second opinion in writing to confirm that this individual has met all criteria (1, 2). A ten-day period of reflection is allotted between the final written request and the delivery of MAID, but if it is foreseeable that the individual's ability to consent may become compromised, a shorter period can be granted if the attending and consulting clinicians are in agreement (1–3). The clinician must then inform the pharmacist dispensing the medications that the prescription is for MAID (1, 2). At the time of MAID administration, the individual must be capable of giving additional consent and must have a final opportunity to withdraw (1, 2). The Chief Coroner is then notified of the MAID death and will complete the Medical Certificate of Death (2, 3).

The Office of Chief Coroner then completes a standardized form, which was specifically developed and is used for the collection of data on MAID deaths in the province of Ontario (Appendix A). The manner of death is classified as suicide since the administered medications would have caused the death and the individual knew the consequences of his or her choice and intended to die (4). Currently, the cause of death for MAID cases is ascribed to the combination of drug toxicity and the underlying condition, illness, and/or disability that precipitated the request for MAID, and is documented in the contributing factor section (4). With upcoming changes in the legislation, we may see the underlying disease, illness, and/or disability that led to the MAID request documented as the sole cause of death (4).

Telemedicine is the act of providing health care services at a distance via online communication and information technology. It may be used in the MAID process at the clinician's discretion, so long as patient assessment meets all criteria provided by the federal legislation, and is clinically sound (3). The proposal for advanced directives, which are provisions specifying future health care decisions if the individual is no longer able to make decisions and MAID requests made by substitute decision-makers were not included in the federal legislation. Therefore, the request must be made by a patient capable of giving informed consent to MAID (3). Based on the legislation, an individual with a mental illness as the primary diagnosis which prompted the request for MAID has been interpreted as ineligible because of unmet criteria (3). “Mature minors” are also currently ineligible for MAID, as the criteria states only adults 18 years and older are eligible (1). The Minister of Justice and the Minister of Health have initiated the process of independent reviews for issues relating to advanced directives, mental illness, and mature minors, and reports will be made by no later than December 2018 (1).

The provincial government of Ontario has also released the recent Medical Assistance in Dying Statute Law Amendment Act (Bill 84) to address issues from gaps in the federal legislation (5). It includes ensuring MAID patients are not denied any benefits, and it maintains the anonymity of MAID providers from Freedom of Information requests. However, it does not necessarily protect clinicians who object to provide MAID from being required to participate in the MAID process. The government also agreed to begin a care coordination service for patients without a physician or with a physician who objects to provide MAID. It is a self-referral system that offers access to MAID-related services and advice. Rules under the Coroners Act were also changed so that the coroner's involvement in MAID death investigation is no longer automatic (4, 5).

Quebec

In the province of Quebec, there are some differences in MAID legislation, which is referred to as “medical aid in dying” in this province. The corresponding legislation includes Bill 52, an act respecting end-of-life care, which was introduced in the Quebec National Assembly on June 12, 2013, and received Royal Assent on June 5, 2014 (6). However, it was not until December 10, 2015 that the majority of the act's provisions came into effect (7). Quebec legislation allows for voluntary euthanasia, also known as physician-assisted dying under the federal legislation, meaning that self-administered MAID is not permitted (6). The eligibility criteria for MAID is similar to the Criminal Code in that it restricts MAID to an individual insured under the Health Insurance Act, who is at least 18 years of age, is capable of giving informed consent, is in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability, and experiences physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved in a tolerable manner, according to the patient (1, 6, 8). A slight difference between the Criminal Code and Quebec law is that the Criminal Code states the individual must have a grievous and irremediable medical condition, a serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability, and includes that natural death has become reasonably foreseeable (1, 8). Quebec's legislation states the individual must be at the end of life and suffering from a serious and incurable illness but it does not include death being reasonably foreseeable (6, 8).

Other Jurisdictions with Formal Legislation

On a global scale, there are currently three countries in addition to Canada that have formal legislation on MAID across the whole country: the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg (4). The United States also has formal legislation on MAID, however only in specific states (4). Before examining the MAID patient demographics in Ontario, we will first explore existing patient demographics in these countries.

United States

There are five US states that have legalized MAID through Death with Dignity laws: Oregon (Death with Dignity Act, 1997), Washington (Death with Dignity Act, 2009), Vermont (An Act Relating to Patient Choice and Control at End of Life, 2013), California (End of Life Option Act, 2015), and Colorado (Proposition 106, End of Life Options Act, 2016) (4, 9–13). The laws across these states are similar to one another in that MAID must be self-administered and it is limited to terminally ill patients with a six-month prognosis (4, 9–13). The state of Montana also has legalized self-administered MAID by court decision (Death with Dignity Act, 2009) (4, 14). Out of the five US states, only Oregon and Washington have published reports with MAID statistics, which will be examined further.

Based on the state of Oregon's Death with Dignity Act 2015 data summary, 218 patients received prescriptions for self-administered MAID but only 125 patients ingested the medication (15). There were a total of 1545 written prescriptions since the law was passed in 1997, but only 991 patients died from ingesting the medication (15). However, during the years of 2014 and 2015, the number of written prescriptions increased by an average of 24.4% (15). In 2015, the majority of patients were 65 years or older (78%) and white (93.1%), 43.1% were well educated (had a baccalaureate or higher degree), and 39.7% were married (15). Based on these data, 42.4% were male and 57.6% were female but this ratio was not always the case. There were only five documented years with a greater number of female recipients (15–31). In total, there have been 509 males and 482 female MAID recipients since the law was passed and the amount of females increased 10.6% between 2014 and 2015 (15, 16). In 72% of patients, cancer was the primary diagnosis that led to MAID deaths, as well as cardiovascular disease (6.8%), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (6.1%), and chronic lower respiratory disease (4.5%), in that order of prevalence. Cancer and ALS as the primary diagnoses for MAID deaths have slightly decreased over the years, with more cases of cardiovascular disease being primarily observed since 2012 (15–31). Compared to an average of earlier years (2.0%), the number of cardiovascular disease-related MAID cases increased to the aforementioned 6.8% in 2015 (15–31). In 2015, most patients died at home (90.1%), 92.2% had hospice care, and 99.2% possessed some kind of health insurance (15). The frequently cited end-of-life concerns were decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable, loss of autonomy, and loss of dignity (15). A total of 106 physicians wrote prescriptions in 2015 and the overall MAID deaths represented a rate of 38.6 per 10 000 deaths in 2015 (15). The medications used were secobarbital (86.4% of cases), phenobarbital/chloral hydrate/morphine sulfate mix (12.1%), phenobarbital (0.8%), and a minority of others (0.8%). Although the Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2016 data summary was recently released, it was excluded to maintain consistency with available 2015 reports from the state of Washington and other countries.

According to the Executive Summary of the 2015 Death with Dignity Act Report of the Washington State Department of Health, 213 patients received prescriptions for self-administered MAID but only 202 were known to have died, with only 166 confirmed deaths from ingestion of the medications (32). Since 2009, there has been a total of 938 prescriptions written, with 917 deaths from MAID (32). In 2015, 72% of individuals had cancer as the primary diagnosis that led to the MAID request, 8% had a neurodegenerative disease inclusive of ALS, 6% had a respiratory disease, and 9% had cardiovascular disease (32). The trends show a decreasing number of MAID deaths associated with cancer and ALS in contrast with an increasing number of deaths as a result of cardiovascular disease, similar to Oregon (32–38). Almost all individuals (95%) had some form of medical insurance, 86% died at home, and 81% were enrolled in hospice care in 2015 (32). The demographics suggest that 53% of MAID recipients were male and 47% were female and a larger proportion of males was noted in all but two years since the law was passed in 2009 (32–38). The age range was 20-97 years, with the majority being between 65 and 74 years (31%), which has been the case each year since 2009 (32). The majority of patients were white (98%), 47% had a baccalaureate or higher degree, and 47% were married (32). Similar to Oregon, loss of autonomy, decreased ability to engage in activities making life enjoyable, and loss of dignity were the three most frequently cited reasons for requesting MAID (32). A total of 142 physicians wrote prescriptions in 2015, which consisted of secobarbital (52%), phenobarbital (46%), pentobarbital (1%), and a minority of others (1%).

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act (2002) legalized MAID for patients being treated by doctors in the country; however, physician-assisted dying was legally and professionally tolerated since the 1980s (4, 39). The Netherlands permits clinician-administered and self-administered MAID including advanced directives for patients 16 years and older as well as access for minors 12 years of age and older with parental consent (40–42). Mental illness as a sole purpose for the request of MAID is also possible in the Netherlands as long as it complies with the Dutch criteria that the request is made voluntarily after great consideration, the patient's suffering was lasting and unbearable, there is no other reasonable alternative to the patient's situation, and at least one other independent physician is consulted in the process (39–42). The numbers of reported MAID cases have increased from 1882 cases in 2002 to 5516 cases in 2015 (39, 43). Of the 5516 cases reported in 2015, 5277 were clinician-administered, 208 were self-administered, and 31 were a combination of both (43). Cancer was the leading health condition in those who chose MAID (72.5%), and cardiovascular disease (4.2%), pulmonary disorders (3.8%), multiple geriatric syndromes (3.3%), mental disorders (1.0%), dementia (2.0%), neurological disorders (5.6%), and other conditions were also listed (43). In 2015, approximately 80% of patients died in their respective homes, 8.4% died in a nursing home or care home, 6.4% died in a hospice setting, and even fewer in a hospital setting (3.5%) (42, 43). According to the 2010 statistics, 41.1% of individuals who received MAID were between the ages of 65 and 80 years of age, 34.3% were between 17 and 65 years of age, and 24.6% 80 years and older (44).

Belgium

Clinician-administered MAID was legalized in Belgium through the Belgian Act on Euthanasia (2002) for patients in medically futile conditions with constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering from a serious or incurable disorder caused by an illness or accident that cannot be alleviated (45). Advanced directives and requests from mental illness are permitted under this Act, which was also accompanied by a 2014 amendment, extending MAID to minors (4, 45–47). Minors must be terminally ill, suffer from intolerable and inescapable physical pain, possess capacity of discernment, have been verified by a psychologist, and have consent of the parents (4, 46–47). In Belgium, MAID deaths are reported as deaths from natural causes for the purpose of contracts, specifically insurance contracts (45). In 2015, there were 2022 cases of MAID in Belgium, and since 2002 there have been 12 726 cases (48). Out of the 2022 cases in 2015, 51.9% were male, and 48.1% were female (48). The majority of MAID cases (84.1%) were aged 60 years or older and similar numbers were seen in the percentage of patients who died at home (44.6%) and in the hospital (41.5%). However, MAID deaths in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities continue to increase (4, 48). Cancer was also the primary medical condition that led to MAID deaths (67.8%).

Luxembourg

Luxembourg legalized clinician-administered and self-administered MAID through the enactment of the Law on Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide (2009) and the Law Relating to Palliative Care, Advanced Instructions, and End-of-Life Accompaniment (2009) with the addition of specific grounds for the exclusion of criminal proceedings (4). Advanced directives and mental illness as a sole purpose for the request of MAID are permitted (49). From 2009 to 2014, there were only 34 MAID cases, 33 of which were clinician-administered and one self-administered (50). Interestingly enough, there were only seven cases in 2014, which consisted of two males and five females (50). All were over the age of 60 and the majority (approximately 71%) died in a hospital setting (50). Cancer was listed as the primary medical condition leading to MAID deaths for 86% of individuals (50).

Other Jurisdictions with Legislation

Switzerland

In addition to these countries with formal legislation on MAID, there are also jurisdictions with different regulations. Switzerland, for example, is the only jurisdiction with statutory exception for self-administered MAID (4). Since the 1940s, Article 115 of the Swiss Criminal Code (1942) allowed any individual to assist in the suicide of another in the absence of selfish motives (4, 49, 51). Self-administered MAID in Switzerland is legal for residents, nonresidents, and minors with sound judgment, irrespective of the condition of the individual who wishes to die (4, 51). Exit and Dignitas are Switzerland's two main “right-to-die” organizations that cater to these individuals seeking assisted suicide (4, 51). According to Swiss statistics, there were 742 assisted suicide cases in 2014, and the numbers have increased annually since 2008 (52). More females have used assisted suicide since 2001, and 94% of individuals were 55 years or older between 2010 and 2014 (52). Between the same years of 2010 to 2014, 42% of cases had cancer, 14% had neurodegenerative conditions, 11% had cardiovascular disease, and 3% had depression (52).

Columbia, Japan, and the United Kingdom

Columbia became the first jurisdiction with case-mandated legal status to allow MAID on constitutional grounds in 1997, which implied that physicians could not be prosecuted for performing euthanasia if the patient 1) had a terminal illness, 2) had requested and consented to death, and 3) no medical treatments existed (4). New regulations were implemented in 2015 requiring the formation of medical committees to evaluate euthanasia requests and advise patients and family members (4).

Japan's euthanasia policy was decided in two local court cases, despite the absence of official laws on euthanasia (4). The findings in those court cases were not upheld at the national level but there is a tentative legal framework for implementing euthanasia (4).

The United Kingdom is also a jurisdiction with prosecutorial guidelines in which the Policy for Prosecutors in Respect of Cases of Encouraging or Assisting Suicide was introduced in 2010 (4). This document provides guidance to prosecutors regarding public interest considerations in cases of assisted suicide (4). Additionally, the Northern Territory of Australia legalized MAID in July 1996, but the legislation was overturned nine months later (49).

Overall, the available reports from countries with formal MAID legislation indicate some common patient demographics for those who chose MAID and includes individuals over the age of 60 and those with cancer. The ratio of males to females varied but remained relatively equal in number. A large proportion of individuals received MAID in the comfort of their own homes and the majority opted for clinician-administered MAID in countries where both options for MAID are available.

After careful consideration of these findings, selected patient demographics and characteristics of the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario between June 2016 and November 2016 were analyzed for comparison with existing data from other jurisdictions. To understand which populations in Ontario are using MAID and under what circumstances, the categories of variables chosen for analysis will be discussed in detail. Because MAID has not yet been practiced for a full year in Canada, there was not enough existing data to provide a comparison with the annual MAID statistics from other countries, but identified trends from the published global statistics will be discussed.

Methods

Population

Case data from the first 100 recipients of MAID in Ontario were collected and analyzed from June 17, 2016 onwards with the final case having occurred in November 2016. The population consisted of all patients in Ontario who died by MAID and fulfilled the eligibility criteria of being at least 18 years of age, had a Canadian government-funded health service, were capable of health-related decision-making, and had a grievous and irremediable medical condition. Because the nature of this study is a demographical analysis, data from the patients was not stratified based on age and sex. The first 100 cases were used as the data set for easy statistical management. This sample will be compared annually with larger sample sizes to better establish MAID trends in Ontario. Additionally, future comparisons can be made with other Canadian provinces once comparable data become available.

Variables Studied

The variables chosen for analysis from the MAID database were grouped into five categories. These consisted of:

Category 1: A broad description of the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario that occurred between June and November 2016. This included both clinician-administered and self-administered MAID cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Category 1, Description of the First 100 Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Cases in Ontario from June 2016 to November 2016

| MAID Cases | N |

|---|---|

| Number of MAID cases | 100 |

| Clinician-administered | 99 |

| Self-administered | 1 |

Category 2: This consisted of the patient characteristics variables of MAID cases in Ontario such as age at death, sex, province of residence, palliative care status, and the setting of MAID administration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Category 2, Patient Characteristics of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Cases in Ontario

| Patient Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at Death* | |

| 18-34 | 0 (0%) |

| 35-44 | 2 (2.1%) |

| 45-54 | 3 (3.1%) |

| 55-64 | 17 (17.5%) |

| 65-74 | 31 (31.9%) |

| 75-84 | 28 (28.9%) |

| 85+ | 16 (16.5%) |

| Mean age | 73.3 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44 (44.0%) |

| Female | 56 (56.0%) |

| Province of Residence | |

| Ontario | 100 (100%) |

| Palliative Care | |

| Receiving palliative care at time of request† | 85 (85.9%) |

| Not receiving palliative care at time of request† | 14 (14.1%) |

| Previously received palliative care‡ | 32 (36.0%) |

| Did not previously receive palliative care† | 57 (64.0%) |

| Palliative care was offered§ | 96 (98.0%) |

| Palliative care not offered§ | 2 (2.0%) |

| MAID Setting¶ | |

| Hospital | 38 (39.6%) |

| Hospital Ward | 22 (22.9%) |

| Critical Care Unit | 6 (6.3%) |

| Long-Term Care Home | 7 (7.3%) |

| Private Residence | 44 (45.8%) |

Age at death calculated with N=97.

Palliative care at time of request calculated with N=99.

Previously received palliative care calculated with N=89.

Palliative care offered calculated with N=98.

MAID setting calculated with N=96. Some participants selected more than one MAID setting thus resulting in a total greater than 100%.

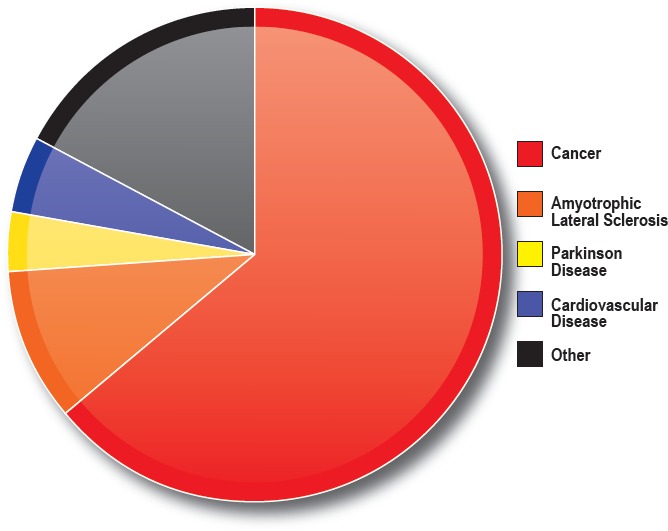

Category 3: This category looked at the nature of the primary medical diagnoses and patient suffering that led to the request for MAID. Primary medical diagnoses such as cancer, ALS, Parkinson disease, cardiovascular disease, respiratory conditions. and all others were included. Whether or not the patient had physical and/or psychological suffering was also included in this section (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Table 3.

Category 3: Primary Medical Diagnosis and Patient Suffering Associated With the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Request

| Medical Diagnoses | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 64 (64.0%) |

| Lung | 10 (10.0%) |

| Breast | 7 (7.0%) |

| Colorectal | 7 (7.0%) |

| Pancreatic | 6 (6.0%) |

| Prostate | 6 (6.0%) |

| Brain | 6 (6.0%) |

| Ovarian | 5 (5.0%) |

| Upper gastrointestinal (GI)* | 4 (4.0%) |

| Other† | 13 (13.0%) |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 10 (10.0%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 (5.0%) |

| Parkinson disease | 4 (4.0%) |

| Other‡ | 17 (17.0%) |

| Physical Suffering§ | N (%) |

| Yes | 98 (99.0%) |

| No | 1 (1.0%) |

| Psychological Suffering¶ | N (%) |

| Yes | 72 (73.5%) |

| No | 26 (26.5%) |

Upper gastrointestinal cancers included cancer of the esophagus, stomach, and gastroesophageal junction.

Other cancers had ≤3 cases. These included various cancers of the bladder, tonsils, kidney, liver, bile duct, skin, larynx, endometrium, plasma cells, and glandular structures in epithelial tissue.

Other medical diagnoses had ≤3 cases.

Physical suffering calculated with N=99.

Psychological suffering calculated with N=98.

Figure 1.

Category 3: Primary medical diagnoses that led to the medical assistance in dying (MAID) request.

Category 4: This category of variables included information about the clinicians involved in the administration of MAID and investigated the nature of the attending clinician at the time of death (physician or nurse practitioner), the physician's field of specialization, whether or not the attending clinician and patient had an existing professional relationship, the assistant's profession, and use of the clinician referral service (Table 4).

Table 4.

Category 4: Information on the Attending Clinician

| Attending Clinician at Time of Death | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Physician | 84 (84.0%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 0 (0.0%) |

| Did not respond | 16 (16.0%) |

| Specialities* | |

| Family medicine | 33 (30.0%) |

| Palliative care | 30 (27.3%) |

| Anesthesiology | 14 (12.7%) |

| Internal medicine | 6 (5.5%) |

| Emergency medicine | 3 (2.7%) |

| Intensive care/critical care | 3 (2.7%) |

| Neurology | 2 (1.8%) |

| Other† | 5 (4.5%) |

| None | 1 (0.9%) |

| Did not respond | 13 (11.8%) |

| Attending Clinician and Patient had Existing Relationship‡ | |

| Yes | 32 (32.3%) |

| No | 67 (67.7%) |

| Assistant's Profession§ | |

| MD | 34 (32.1%) |

| RN | 10 (9.4%) |

| Other¶ | 1 (0.94%) |

| Did not respond | 61 (61%) |

| Referral Request From the Clinician Referral Service | |

| Yes | 17 (17%) |

| No | 22 (22%) |

| Unknown | 7 (7%) |

| Did not respond | 54 (54%) |

| Other Consulted Health Provider's Specialty | |

| Palliative care | 6 (6.1%) |

| Psychiatry | 6 (6.1%) |

| Other** | 9 (9.1%) |

| Did not respond | 78 (78.8%) |

| Other Consulted Health Providers Second Specialty†† | |

| Family medicine | 1 (1.0%) |

| Palliative care | 1 (1.0%) |

| Neurology | 1 (1.0%) |

| Psychiatry | 2 (2.0%) |

| Oncology | 2 (2.0%) |

| Did not respond | 92 (92.9%) |

More than one profession was listed in some cases thus resulting in a total greater than 100%.

Other specialties include hospitalist, FRCP, FRCPC, general surgery, and oncology.

Attending clinician and patient had existing relationship calculated with N=99.

More than one assistant was listed in some cases thus resulting in a total greater than 100 percent.

Other assistant's profession included a physician assistant student that was present with the MD.

Other specialties had ≤2. One indicated general practitioner as a specialty, which was excluded. Calculated with N=99.

Two cases indicated duplicates of the first specialty listed, and were therefore omitted. One of these indicated two specialties. Calculated with N=99.

Category 5: This category focused on the MAID process itself, including details such as the number of previously denied MAID requests, proxy or third party involvement, the ten-day reflection period, pharmacist notification of the purpose of the prescription for MAID, the types of medications used for the administration of MAID, and any problems encountered while accessing MAID (Table 5). The numbers and percentages of each variable were calculated using the responses obtained from the submitted individual MAID reports as completed by clinicians (Appendix A).

Table 5.

Category 5: Details on the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Process

| Details | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Denied MAID Requests* | 3 (3.4%) |

| Proxy or Third Party Involvement† | 12 (12.0%) |

| Ten-Day Reflection Period Followed‡ | |

| Yes | 79 (79.8%) |

| No | 20 (20.2%) |

| Pharmacist Notified of Purpose of Prescription | |

| Yes | 61 (61.0%) |

| No | 4 (4.0%) |

| Did not respond | 35 (35.0%) |

| Medications Used | |

| Propofol | (99.0%) |

| Midazolam | (93.0%) |

| Rocuronium | (88.0%) |

| Lidocaine | (80.0%) |

| Bupivicaine | (23.0%) |

| Potassium§ | (4.0%) |

| Other | (23.0%) |

| Problems Accessing MAID¶ | |

| Yes | 16 (16.3%) |

| No | 82 (83.7%) |

| Recorded Cause of Death** | |

| Combined/mixed/drug toxicity with or without medical diagnoses listed | 91 (97.8%) |

| Intoxication with listed medications and medical diagnoses | 2 (2.2%) |

Denied MAID requests calculated with N=87. This excludes those who did not respond, unknowns, and one unclear response.

Used “Other person if unable-18 years or older” column to calculate proxy involvement.

Ten-day reflection period calculated with N=99.

Two cases indicated “off” for potassium but listed PM under the time potassium was administered. It was unclear if potassium was administered. The two cases were not included in calculation.

Problems accessing MAID calculated with N=98.

Recorded cause of death calculated with N=93.

Procedure

Approval for this study was obtained from the Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa. Anonymized patient demographic data for the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario was obtained in electronic form from the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. The data provided had been anonymized through removal of all identifying patient demographics. As only anonymized data was to be analyzed, it was not necessary to seek and obtain approval from the university's Research and Ethics Board.

Results

Category 1: Description of the MAID Cases

MAID cases in Canada are classified as either clinician-administered or self-administered. In the Ontario cohort studied, the majority of cases had been clinician-administered MAID. There were 99 clinician-administered MAID cases and only one self-administered MAID case between June 2016 and November 2016. The majority of Ontarians who had requested MAID had opted for clinician-administered MAID. Although this cohort is only a sample of all eligible patients who had requested MAID in Ontario thus far, the numbers are consistent with the patterns seen in the Netherlands and Luxembourg, which are the only two other countries that offer both clinician-administered and self-administered MAID. In those two countries, a significantly larger proportion of patients are receiving clinician-administered MAID over self-administered MAID. It is interesting to note that offering only self-administered MAID in the United States revealed a fair number of eligible individuals who had been prescribed the medications but did not actually ingest them, especially in Oregon. Since 1997, 554 patients in the state of Oregon had been prescribed MAID medications but did not ingest them for reasons unknown.

Category 2: Patient Characteristics

The majority of MAID recipients were older adults. At the time of death, 17.5% of patients were between the ages of 55 and 64; 31.9% between 65 and 74; 28.9% between 75 and 84; and 16.5% 85 and over. Only 5.2% of patients were between the ages of 35 and 54 at the time of death, and no MAID recipients were young adults aged 18 to 34. It must be recalled that the majority of MAID recipients in Oregon, Washington, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg were aged 60 and older, which is similar to the Ontario statistics for this sample population.

There were slight differences between male and female MAID recipients in that 56% were female and 44% were male. The ratio of female to male MAID recipients in Ontario was nearly identical to that of Oregon, and the state of Washington and Belgium showed a similar trend, however with slightly more males than females.

All of the patients resided in Ontario, which corresponded with the provincial residence requirement outlined in the MAID eligibility criteria.

Only 36% of patients had previously received palliative care prior to the MAID request. Ninety-eight percent of patients were offered palliative care as part of the MAID process and the majority of patients had been receiving palliative care at the time of the MAID request (85.9%).

As for the setting in which MAID was administered, most patients opted for a private residence (44.9%), hospital (38.8%), or hospital ward (22.5%). Fewer patients received MAID in a long-term care home (7.1%) or critical care unit (6.1%). In Oregon, Washington, and the Netherlands, the majority of patients died in a private residence (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summarized Patient Demographics in Jurisdictions With Formal Legislation on Medical Assistance in Dying

| Jurisdiction | Clinician-Administered or Self-Administered | Age | Sex | Primary Medical Diagnosis | Setting | Hospice Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oregon (2015) | 125 self-administered | 78% 65+ |

42.4% male, 57.6% female |

72% cancer, 6.8% cardiovascular disease, 6.1% amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), 4.5% chronic lower respiratory disease *cancer and ALS have decreased, seeing more cardiovascular disease |

90.1% at home | 92.2% yes |

| Washington (2015) | 166 confirmed self-administered | 31% 65-74 |

53% male, 47% female |

72% cancer, 8% neurodegenerative disease, 6% respiratory disease, 9% cardiovascular disease *cancer and ALS have decreased, seeing more cardiovascular disease |

86% at home | 81% yes |

| Netherlands (2015) |

5277 clinician-administered. 208 self-administered. 31 combination |

41.1% 65-80. 34.3% 17-65. 24.6% 80+ (2010) |

72.5% cancer, 4.2% cardiovascular disease, 3.8% pulmonary disorders, 3.3% multiple geriatric syndromes, 1% mental disorders 2% dementia, 5.6% neurological disorders |

80% at home, 8.4% nursing or care home, 6.4% hospice, 3.5% hospital |

||

| Belgium (2015) | 2022 clinician-administered | 84.1% 60+ |

51.9% male, 48.1% female |

67.8% cancer |

44.6% at home, 41.5% hospital. *Nursing homes and long-term care facilities are increasing |

|

| Luxembourg (2014) |

33 clinician-administered, 1 self-administered |

100% 60+ |

2 male, 5 female |

86% cancer | 71% in a hospital | |

| Ontario: First 100 Cases (2016) |

99 clinician-administered, 1 self-administered |

77.3% 65+ |

44% male, 56% female |

64% cancer. 10% ALS, 5% cardiovascular disease, 4% Parkinson disease |

39.6% hospital, 22.9% hospital ward, 6.3% critical care unit, 7.3% long-term care home, 45.8% at home |

85.9% had palliative care at time of request, 36% previously received palliative care |

Although this Ontario sample population showed a high number of individuals who died at home, there were also many who died in a hospital setting, just as was the case in Belgium. This differs greatly from the United States, where there were no MAID recipients in both Oregon and Washington who died in a hospital setting in 2015 (15, 32). This could possibly be related to the fact that only self-administered MAID is regulated in the US and hospital stays can be very expensive.

Category 3: Primary Medical Diagnosis and Patient Suffering

The most common primary medical diagnosis that led to death by MAID was cancer (64%). The types of cancer varied but the most prevalent were lung (10%), breast (7%), and colorectal (7%). Pancreatic, prostate, and brain cancer each comprised 6% of the patients' primary medical diagnoses with ovarian cancer (5%) and upper gastrointestinal tract cancer (4%) being next in line. A total of 13% of patients had other types of cancer as their primary medical diagnosis with each type contributing only three or less cases. The other less prevalent types of cancer originated in the skin, bladder, tonsil, kidney, liver, uterus, larynx, and other sites.

Besides cancer, other primary medical diagnoses included ALS (10% of cases), Parkinson disease (4%), and cardiovascular disease (5%). The other, less prevalent medical diagnoses constituted three or less cases and represented 17% of the total sample population and included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Huntington disease, muscle wasting, myositis and paralysis, cirrhosis of the liver, renal failure, neurosyphilis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid and osteoarthritis, myelodysplastic syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, and systemic lupus erthyematosus.

Almost all individuals (99%) had cited physical suffering as part of patient rationale for requesting MAID. The common forms of physical suffering experienced were pain; fatigue and muscle weakness; weight loss and anorexia; nausea, vomiting, and incontinence; difficulties with hearing, vision, and speech; loss of muscular control and paralysis; metastases, edema and gangrene; and others.

A large proportion of patients (73.5%) had indicated psychological suffering, which included anxiety and fear; with loss of independence and dignity; poor quality of life and lack of enjoyment; stress and hopelessness; a family member/friend who had died of the same illness; not wanting to be a burden on the family; and a lack of friends as their reasons. Physical and psychological relief efforts were attempted to help comfort the patients and ease the pain through the delivery of pain medication, palliative and end-of-life care, community and family support, counseling, spiritual support, and personal care.

In the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, the states of Oregon and Washington, and also Switzerland, cancer was the primary medical diagnosis that had led to MAID deaths and this is also the case in Ontario. However, Oregon and Washington indicated a slight decrease in the number of MAID deaths related to cancer and ALS with an increase in cardiovascular disease-related deaths. Although the percentage of medical diagnoses leading to MAID deaths in Ontario is low for cardiovascular disease, we may begin to notice an increase in number as MAID reports continue to come in.

Category 4: Clinician Attendance

Analysis of the type of clinician in attendance at the time of death indicated that the overwhelming majority (84%) were physicians. No nurse practitioners were indicated as being the attending clinician, but data for this section of the MAID report were not available for 16 cases. The most frequent specialties of the attending physicians were family medicine (30%), palliative care (27.3%), and anesthesiology (12.7%), but a notable portion of data (11.8%) was unavailable for this section of the MAID report. Patients who had an established, preexisting professional relationship with the attending clinician (67.7%) were more than twice than those who did not (32.3%).

For the medical assistants in attendance at the time of MAID administration, 61% of this data was not available, 32.1% were physicians, 9.4% were registered nurses, and one assistant was listed as a physician assistant student.

In the MAID process, there is an independent second clinician who confirms in writing that the patient meets the eligibility criteria for MAID. Information on the utilization of the Clinician Referral Service indicated that 17% of clinicians utilized the service and 22% did not, but 61% of the data was not available. Regarding the other consulted health provider's specialties, 78.8% of data was not available for the first specialty and 92.9% was not available for the second specialty. In those MAID reports where the section had been completed, 6.1% of the consulted clinicians had palliative care and psychiatric specialties respectively. Other specialties such as neurology, respiratory, nephrology, oncology, family medicine, clinical ethics, and social work were represented in 9.1% of the sample population. The clinicians with a second specialty were listed as being psychiatry and oncology (2.0% respectively), family medicine, palliative care, and neurology (1.0% respectively).

The data pertaining to information recorded on the attending clinician in the submitted MAID reports indicated that this data was frequently not available as a result of not having been completed. One potential reason for this could be that the clinicians wanted to maintain the utmost anonymity because, despite being legal, MAID practice in Canada is a new and controversial concept and there may be fears of how their involvement in the provision of MAID will be perceived by colleagues and possibly the public, should their identity become known. Due to other countries having limited published information on clinicians involved in the MAID process and with the statistics for Ontario in this initial cohort being fairly incomplete, no valid trends or comparisons can be made. Nonetheless, the Ontario MAID report includes more information on the clinicians who administer MAID than can be obtained from the published reports on MAID from other countries. Accumulation of this data could provide valuable information for the MAID process in the future if this section is completed accordingly by clinicians.

Category 5: The MAID Process

Within the first 100 MAID cases, only 3% of patients reported previous denial of their request for MAID with subsequent approval. The reasons cited for their initial denial of MAID were that their requests had been made before MAID was legalized (which would have been appropriate at that time) and that their death was not deemed to be imminent at the time of request. One case was not included in this calculation because the stated reason was unclear.

Twelve percent of cases involved the utilization of a proxy or third party to make the written request for MAID in the presence of two independent witnesses, if the patient was unable to sign and date the request. The reasons cited for the utilization of a proxy was a lack of voluntary movement, absence of muscular strength, and an inability to write. The ten-day reflection period between the date of the signed MAID request and the day on which MAID was administered was utilized by 79.8% of patients. In 20.2% of cases, this time frame was shortened due to a subsequent loss of capacity to provide patient consent or that death had become imminent. Specific reasons provided for the shortened time frame were loss of capacity, rapid functional decline, severe pain, persistent requests, inconvenient timing of the death in relation to other familial life events, increased oral secretions, drowsiness, and the inability to eat or drink.

The pharmacist was informed about the purpose of the MAID prescription in only 61% of cases when that prescription was being procured by the clinician. Four percent of clinicians did not inform the pharmacist of the intended use of the prescription and no data was available for 35% of the cases. The MAID regulations require clinicians to notify the pharmacist of the purpose of the MAID medications before they are dispensed; however, some physicians listed that they did not abide by these regulations (2).

The medications used for the administration of MAID were propofol (99%), midazolam (93%), rocuronium (88%), lidocaine (80%), bupivacaine (23%), potassium (4%), and others (23%). In two cases, it was unclear if potassium had been administered as part of the drug regimen (conflicting information provided on the completed form) and these cases were therefore not included in calculation. The medications chosen for the administration of MAID in Ontario did differ from the use of secobarbital, phenobarbital, chloral hydrate, morphine sulfate, and other mixtures of medications in the United States (15, 32), thiopental and morphine use in Luxembourg (50), and thiobarbital use in Belgium (48).

Many patients (83.7%) did not experience any issues in accessing MAID but 16.3% did. The specific problems encountered included MAID not being provided in a nursing home, which necessitated a transfer to a different setting for drug administration, delayed access of MAID as a consequence of only one MAID case being allowed per week, medical questioning that resulted in a delay in administration, clinicians not acting upon an initial request for MAID, and delay and complications in securing medications for home use. As for the cause of death recorded by the coroner, in 97.8% of cases it was recorded as the respective combined/mixed/drug toxicity, with or without the primary medical diagnosis which had precipitated the request for MAID. There were two cases (2.2%) in which the cause of death was documented as “intoxication” from the administered medications with listing of the medical diagnosis.

The majority of family members indicated remarks supportive of the patient's MAID decision and most were positive about the MAID experience. However, there were two concerns listed by family members. One concern was that, although they were comfortable with the MAID process, there were issues with the primary medical diagnosis and classification of the manner of death as suicide. The other concern was about the patient's loss of cognition arising from an increase in medication. Some other unique issues and concerns about the MAID process were also listed and included the need for more detail in the medical records, difficulties encountered in using the telemedicine option for a second assessor of the patient, not having a defined prognosis, poor documentation, the rules on the period of reflection not being followed, issues around the management of MAID cases when the clinician is on holiday, and inappropriate signatures. One report also indicated that the clinician was not provided with the document to record the provision of MAID.

Discussion

Although the MAID data form is currently being revised, a few suggestions can be made to improve documentation of patient characteristics. One recommendation is to incorporate race/ethnicity, marital status, highest education level achieved, and regional area of residence in Ontario into the MAID data report. This would increase the amount and quality of information that can be derived from MAID deaths in Ontario and will provide valuable statistics for the public, legislators, researchers, and clinicians in the future.

The removal of the ward and critical care unit options for the MAID administration setting on the data forms or the reclassification of ward and critical care unit options listed under the hospital setting option is another recommendation. This would increase the accuracy of responses in this section as many discrepancies were encountered. Ensuring that the clinicians complete all the required paperwork before and after the actual administration of the MAID regimen is an important recommendation as it was noted that crucial information was unavailable in a significant number of cases.

This research project was limited to the first 100 cases of MAID in Ontario. The cohort of cases was decisively limited to the first 100 individuals who received MAID in Ontario and is not large enough to make annual comparisons with the published rates and patient demographics from other countries in which MAID is available. Medical assistance in dying is in its early stages in Canada and will not likely show valid trends for some time. Further statistical analysis of larger and annual case uptake will be conducted as the numbers of cases increase so that valid international comparisons can be made.

Conclusion

The introduction of clinician-administered and self-administered MAID in Ontario has brought legal and voluntary end-of-life options to individuals wishing to die in the province. Analysis of the first 100 MAID cases in Ontario revealed that the majority of MAID recipients thus far are older adults with cancer who opt for clinician-administered MAID in either a hospital or at home.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Ontario Medical Assistance In Dying (MAID) Death Data Collection Form

| General Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date of Report | mm/dd/yyyy | |

| Coroner | ||

| Patient Name | ||

| CIS Number | ||

| OHIP number | ||

|

Attending (Pronouncing) Clinician at Time of Death Information |

Type:

Clinician name: Specialties: |

|

| Assistant at Time of Medication Provision If Noted |

Name: Profession: |

|

| Type of MAID |

|

|

| Assistant at Time If Self-Administered? |

If yes provide relationship if known: |

|

| Patient Age | ||

| DOB | ||

| Patient Sex |

|

|

| Province of Residence | ||

| Medical Diagnosis Prompting MAID Request | ||

| Did an Authorized Third Party or Proxy Sign on Behalf of the Requestor? |

Additional details provided later in chart |

|

| Referral and Assessment Process | ||

| Were There Any Previous Requests for MAID That Were Denied? |

If yes: what was the reason the request was denied? |

|

| Eligibility Criteria | Assess if these were considered and review of records support the decisions made | |

| Eligible for Public Health Care Funding |

|

|

| At Least 18 Years Old |

|

|

| Capable to Make Decisions Regarding Health |

|

|

| Grievous and Irremediable Medical Condition | ||

| Serious/Incurable Illness-Disease-Disability |

List: |

|

| Advanced State of Irreversible Decline in Capability |

Supportive findings: |

|

| Illness, Disease or Disability or State of Decline Causes Enduring Physical or Psychological Suffering That is Intolerable to the Patient and That Cannot Be Relieved Under Conditions the Patient Considers Acceptable |

Physical Suffering:

List: Types of relief attempted/offered: Why not tolerable: |

|

|

Psychological Suffering:

List: Types of relief attempted/offered: Why not tolerable: | ||

| Natural Death has Become Reasonably Foreseeable |

–Note: likely interpret as natural course of the disease (not the manner)

Provide prognosis(estimated time) if provided: Supportive findings: |

|

| Did the Attending Practitioner Have an Existing Therapeutic Relationship With Patient? |

Type of relationship: |

|

| i. If Yes, For How Long? | ||

| ii. If No, Did the Request Result From a Referral Through the Clinician Referral Service? | ||

| Were There Consultation(s) With Other Health Providers (Other Than the Required 2nd Opinion). If So, What Other Provider(s) (e.g., Psychiatry, Psychology, Palliative Care Specialist)? (247(5.1) |

Name: Specialty: |

|

| Was the Patient Receiving Palliative Care at the Time of the Request? |

|

|

| Had the Patient Previously Received Palliative Care |

|

|

| Date of First Voluntary Request for MAID (Oral) | Date: | |

|

Made freely—no external pressure or coercion

| ||

|

Free and informed

| ||

| Date First Assessment of Eligibility for MAID Completed |

Initial assessment date: MD/NP notes opinion if meets criteria

Supportive Findings: |

|

| Informed Consent Provided by Patient |

Date: Treatment options discussed:

|

|

|

Informed of potential means to relief their suffering:

| ||

|

Palliative Care offered:

| ||

| Written Request by the Patient | Date: | |

|

Signed by person

If no: why not? |

Other person if unable

|

|

|

Date signed was after told of grievous and irremediable illness

|

||

|

Independent witness ONE

|

Independent witness TWO

|

|

|

Patient informed that they may at any time withdraw consent

|

||

| Second Assessment Written |

Second opinion assessment date: (Note that this is also considered the formal approval date) |

|

|

Independent

| ||

| Reflection Period |

10 day period followed

|

|

|

If No: 1st assessor(or provider of MAID) and 2nd assessor both are of the opinion that

List the rationale to support a reduced reflection period: | ||

| Concerns Regarding Reflection Period (From Coroner) | List: | |

| Notify Pharmacist of Purpose of Prescription |

|

|

| MAID Provision | ||

| Withdrawal Opportunity Provided Just Before MAID |

|

|

| Confirmation of Consent Given Just Before MAID (From Verbal Information During Reporting to Coroner or Documented in the Record) |

|

|

| Date and Time of Death | Date: | Time: |

| Medications Provided Directly to Patient by Physician | List: | |

| Medications Prescribed to Patient for Self-Administration | List: | |

| Time/Dose of Medications to the Time of Death |

Physician administered

|

|

| Recorded Cause of Death by the Coroner | ||

| P/T of Occurrence of Death | ||

| Setting (e.g., Private Residence, Hospital, Nursing Home): |

Hospital □ Ward □ Critical Care Unit □ Long Term Care Home □ Private Residence □ |

|

| What Were the Patient's Concerns that Lead to the Request | Physical—List: | |

| Psychological—List: | ||

| Family Perspectives, Concerns or Other | List: | |

| Family Member Aware of the MAID Process |

|

|

| Were There Any Problems Accessing MAID Identified? |

i.e. non-participating institution, clinician access issue

If yes please list: |

|

| Any Unique Issues/Concerns That Arose During the Investigation Not Captured Elsewhere But Significant to the Case | List: | |

CIS - Coroner's Information System

OHIP - Ontario Health Insurance Plan

DOB - Date of birth

P/T - Province/Territory

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1).Parliament of Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: Government of Canada; c2017. Bill C-14: An act to amend the criminal code and to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying), 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2015-2016; 2016. Jun 17 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=8384014. [Google Scholar]

- 2).The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario [Internet]. Toronto: College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; c2017. Medical assistance in dying, policy statement #4-16; 2016. Jun [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.cpso.on.ca/Policies-Publications/Policy/Medical-Assistance-in-Dying. [Google Scholar]

- 3).The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario [Internet]. Toronto: College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; c2017. Medical assistance in dying policy: frequently asked questions; [cited 2017. Apr 23]. 5 p. Available from: http://www.cpso.on.ca/CPSO/media/documents/Policies/Policy-Items/medical-assistance-in-dying-FAQ.pdf?ext=.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4).Huyer D. (Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, Toronto, ON). Conversation with Alexandra E. Rosso (University of Ottawa - School of Health Sciences). 2017. Apr 20.

- 5).Forman R. Official OMA communication: Medical assistance in dying statute law amendment act (Bill 84). Toronto: Ontario Medical Association; 2017. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 1 p. Available from: http://mailchi.mp/email/medical-assistance-in-dying-statute-law-amendment-act-bill-84?e=96ec39f399. [Google Scholar]

- 6).LégisQuébec [Internet]. Québec City: Gouvernement du Québec; c2017. Chapter S-32.0001: Act respecting end-of-life care; 2014. [cited 2016 Dec 1]. Available from: http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/S-32.0001. [Google Scholar]

- 7).Medical assistance in dying: a patient-centered approach; report of the Special Joint Committee on Physician-Assisted Dying [Internet]. Ottawa: Parliament of Canada; 2016. Feb [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 60 p. Available from: http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/hoc/Committee/421/PDAM/Reports/RP8120006/pdamrp01/pdamrp01-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8).Giroux M. How disputes and liability issues are playing out in Quebec. Paper presented at: Ottawa Conference on Medical Assistance in Dying; 2016. Oct 14-15. Ottawa, ON. [Google Scholar]

- 9).The Oregon death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Health Authority; 1997. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/statute.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10).Washington State Legislature [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Legislature; c2017. The Washington death with dignity act; 2009. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=70.245&full=true. [Google Scholar]

- 11).No. 39. An act relating to patient choice and control at end of life [Internet]. Montpelier (VT): General Assembly of the State of Vermont; 2013. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.leg.state.vt.us/docs/2014/Acts/ACT039.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12).California legislative information [Internet]. Sacramento: California State Legislature; c2017. Assembly Bill No. 15 End of life; 2015. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520162AB15. [Google Scholar]

- 13).Colorado end of life options act [Internet]. Denver: Colorado Secretary of State; 2016 [cited 2017. Apr 23]. 11 p. Available from: https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/Initiatives/titleBoard/filings/2015-2016/145Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14).Montana death with dignity act [Internet]. Helena (MT): Supreme Court of the State of Montana; 2009. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 68 p. Available from: http://cases.justia.com/montana/supreme-court/2009-12-31-DA%2009-0051%20Published%20–%20Opinion.pdf?ts=1396129595. [Google Scholar]

- 15).Oregon death with dignity act: 2015 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2016. Feb 4 [cited 2017. Apr 23]. 7 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year18.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16).Oregon death with dignity act: 2014 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2015. Feb 12 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 6 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17).Oregon death with dignity act: 2013 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2014. Jan 28 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 7 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18).Oregon death with dignity act: 2012 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2013. Jan [cited 2017 Apr23].6p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year15.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19).Oregon death with dignity act: 2011 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2012. Mar [cited 2017 Apr23]. 6 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20).Oregon death with dignity act: 2010 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2011. Jan [cited 2017 Apr23]. 3 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21).Oregon death with dignity act: 2009 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2010. Mar [cited 2017 Apr23]. 5p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22).Oregon death with dignity act: 2008 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2009. Mar [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 5 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23).Oregon death with dignity act: 2007 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2008. Mar [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 5 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24).Oregon death with dignity act: 2006 data summary [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2007. Mar [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 5 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year9.pdf.

- 25).Eighth annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2006. Mar 9 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 24 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year8.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26).Seventh annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2005. Mar [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 25 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27).Sixth annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2004. Mar [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 6 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year6.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28).Fifth annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2003. Mar 6 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 21 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29).Fourth annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2002. Feb [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 17 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30).Oregon' death with dignity act: three years of legalized physician-assisted suicide [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2001. Feb 22 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 20 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31).Oregon death with dignity act: the second year's experience [Internet]. Portland (OR): Oregon Public Health Division; 2000. Feb 23 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 21 p. Available from: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32).Washington State Department of Health 2015 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2016. Mar 25 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33).Washington State Department of Health 2014 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2015. Mar 16 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34).Washington State Department of Health 2013 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2014. Feb 28 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109DeathWithDignityAct2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35).Washington State Department of Health 2012 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2013. Feb 28 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36).Washington State Department of Health 2011 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2012. Feb 29 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 12 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/5400/DWDA2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37).Washington State Department of Health 2010 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2011. Feb 9 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 11 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/5400/DWDA2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38).Washington State Department of Health 2009 death with dignity act report Executive Summary [Internet]. Olympia (WA): Washington State Department of Health; 2010. Feb 3 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 10 p. Available from: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/5400/DWDA2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39).Koopman J.J., Putter H. Regional variation in the practice of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands. Neth J Med [Internet]. 2016. Nov [cited 2017 Apr 23]; 74(9): 387–394. PMID: 27905305. Available from: http://www.njmonline.nl/getpdf.php?id=1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Government of the Netherlands [Internet]. Amsterdam: Government of the Netherlands; c2017. Euthanasia, assisted suicide and non-resuscitation on request; [cited 2017. Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.government.nl/topics/euthanasia/contents/euthanasia-assisted-suicide-and-non-resuscitation-on-request. [Google Scholar]

- 41).Termination of life on request and assisted suicide (review procedures) act [Internet]. Amsterdam: Government of the Netherlands; 2002. Apr 1 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 8 p. Available from: http://www.eutanasia.ws/documentos/Leyes/Internacional/Holanda%20Ley%202002.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42).Kimsma G. The perspectives of providers on assisted dying: lessons from the Netherlands for Canada. Paper presented at: Ottawa Conference on Medical Assistance in Dying; 2016. Oct 14-15. Ottawa, ON. [Google Scholar]

- 43).Regionale Toetsingscommissies Euthanasie: Jaarverslag 2015 [Internet]. Brussels: European Institute of Bioethics; 2015. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 79 p. Dutch. Available from: http://www.ieb-eib.org/nl/pdf/20160427-rapport-euthanasie-pays-bas.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44).StatLine [Internet]. Amsterdam: Statistics Netherlands; c2017. Deaths by medical end-of-life decision; age, cause of death; 2012. Jul 11 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLEN&PA=81655ENG&LA=EN. [Google Scholar]

- 45).The Belgian Act on Euthanasia of May, 28th 2002. Ethical Perspect [Internet]. 2002. [cited 2017 Apr 23]; 9(2-3): 182–8. Available from: http://www.ethical-perspectives.be/viewpic.php?TABLE=EP&ID=59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Raus K. The extension of Belgium's euthanasia law to include competent minors. J Bioeth Inq. 2016. Jun; 13(2): 305–15. PMID: 26842904. 10.1007/s11673-016-9705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Boring N. Brussels: Library of Congress, Global Legal Monitor; c2017. Removal of Age Restriction for Euthanasia; 2014. Mar 11 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/belgium-removal-of-age-restriction-for-euthanasia/. [Google Scholar]

- 48).Commission Fédérale de Contrôle et d'Évaluation de l'Euthanasie: Septième rapport aux Chambres législatives. 7 octobre, 2016, 54e Législature, 3e Session, 2014-2015. [Internet]. Brussels: Chambre des Représentants et Sénat de Belgique; 2016. Oct 7 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 133 p. Available from: http://www.lachambre.be/FLWB/PDF/54/2078/54K2078001.pdf.

- 49).Shariff M.J. Assisted death and the slippery slope- finding clarity amid advocacy, convergence, and complexity. Curr Oncol. 2012. Jun; 19(3): 143–54. PMID: 22670093. PMCID: PMC336476. 10.3747/co.19.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Commission Nationale de Contrôle et d'Évaluation de la loi du 16 mars 2009 sur l'euthanasie et l'assistance au suicide: Troisième rapport à l'attention de la Chambre des Députés. 16 mars 2009, 2013-2014. [Internet]. Luxembourg: Santé.lu; 2017 [cited 2017. Apr 23]. 31 p. Available from: http://www.sante.public.lu/fr/publications/r/rapport-loi-euthanasie-2013-2014/rapport-loi-euthanasie-2013-2014.pdf.

- 51).Geiser U. Cabinet rules out new suicide legislation [Internet]. Swiss Broadcasting Corporation; 2011. Jun 29 [cited 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/cabinet-rules-out-new-suicide-legislation/30575282?uriScheme=http%3A%2F%2F.

- 52).Cause of death statistics 2014: assisted suicide and suicide in Switzerland [Internet]. Neuchâtel (Switzerland): Federal Statistical Office; 2015. [cited 2017 Apr 23]. 4 p. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/publikationen.assetdetail.1023134.html. [Google Scholar]