Abstract

The laryngohyoid complex, composed of the hyoid bone and laryngeal cartilages, can be of interest in the autopsy setting, particularly when injuries are observed. Analysis of trauma to this structure can assist in establishing cause and manner of death. In many situations, the forensic anthropologist, with their expertise in analyzing bone and cartilage trauma, can assist in analyzing trauma to this complex. Although researchers have tried to study the relationships between causes of trauma to the osseocartilaginous structure and the observed injury pattern, they have not been successful in identifying unique signatures associated with different causes of trauma. This is because different causes can result in the same or similar injury patterns. In addition, variation due to growth and development or due to remote injury may change the structure's biomechanical response. The goal of this paper is to address issues that a forensic pathologist may encounter when assessing potential trauma to the osseocartilaginous structures of the laryngohyoid complex; in particular, it focuses on anatomical variants and trauma resulting from various causes.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Forensic anthropology, Neck trauma, Laryngohyoid complex, Strangulation, Hanging

Introduction

Neck trauma observed during an autopsy typically requires closer examination of the laryngohyoid complex. Such trauma can be the result of a variety of actions including violence, therapeutic interventions, accidents, or postmortem processing. These cases include all types of manners where trauma is caused by direct pressure to the neck (e.g., hanging, strangulation, sharp/blunt/ballistic impact to the neck) or indirect pressure from causes like blunt force trauma (e.g., falls, assault, explosion), or sharp force trauma or ballistic trauma to the head, which can cause hyperextension of the neck with subsequent injury to the laryngohyoid complex (1). Although the laryngohyoid complex is well studied in terms of types and locations of injuries, there is a lack of information regarding the forces needed to cause injury to these structures. There are several reasons for this paucity including variations in morphology, biomechanics, and external forces applied. Fractures of the complex may not directly relate to the cause of death; however, it should be considered carefully when other mechanisms are also involved (1). Understanding the anatomy and variations present in the human laryngohyoid complex is valuable when assessing cause and manner of death. As such, this section provides a brief description of anatomy, anatomical variants, and various types of mechanisms leading to trauma that can assist a forensic pathologist in assessing cause and manner of death from the osseocartilaginous structures of the laryngohyoid complex.

Discussion

Anatomy and Development

The laryngohyoid complex is comprised of two structures: the hyoid bone and the cartilaginous larynx (i.e., “voice box”). The hyoid bone makes up the superior boundary of the complex and is located near the base of the mandible, anterior to the cervical spine. The cricoid cartilage of the larynx forms the inferior boundary of the complex. The hyoid bone and larynx are bound together by three ligaments: the thyrohyoid membrane and two lateral thyrohyoid ligaments (2).

Hyoid

The hyoid is a U-shaped bone located at the base of the mandible. It is suspended by the styloid processes of the temporal bone through the stylohyoid ligament (2). The hyoid functions as an attachment site for lingual, pharyngeal, and anterior neck muscles (3). It is composed of five segments: one quadrilateral-shaped central body; two long, tapered greater horns (cornu major); and, two short, tapered lesser horns (cornu minor) (2, 4). The greater horns articulate with the superolateral surfaces of the body and form a synchondrosis (Image 1). This synchondrosis may be mistaken for a fracture in radiographs (5) (Image 2). The lesser horns are small bones or cartilages that articulate on the superior aspect of the synchondrosis on each side of the body (3). There are two groups of muscles that insert into the hyoid: the suprahyoid and infrahyoid (6). The suprahyoid muscles include the mylohyoid, geniohyoid, stylohyoid, and digastric muscles. The infrahyoid muscles include the sternohyoid, omohyoid, sternothyroid, and thyrohyoid muscles.

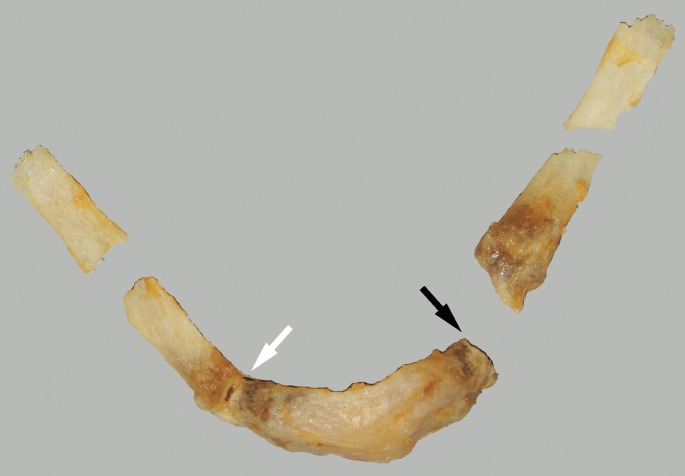

Image 1.

Superior view of a fused hyoid bone. The white arrows indicate the fused synchondrosis connecting the body and the greater horns. The bone has been chemically processed to remove all soft tissue.

Image 2.

A fractured hyoid from a case of a suicidal hanging. The greater horns are fractured. The white arrow indicates a partially fused synchondrosis. The black arrow indicates an unfused synchondrosis. The bone has been chemically processed. Without removal of all soft tissue, the unfused synchondrosis could be mistaken for a fracture.

Embryologically, the hyoid develops from the second and third branchial arches (3). By the end of the embryonic period, all segments of the hyoid are present in their cartilaginous form. The body and greater horns can begin ossifying as early as 30 weeks gestation; however, the lesser horns do not ossify until puberty (7). Although the tendency is for the segments to fuse with increasing age, the fusion rates and patterns are highly variable (8–10). Sexual dimorphism has been noted in the shape and size of the bone, with females having smaller hyoid bones with wider angles (11–13). The degree of fusion in addition to the overall shape has been suggested to be a factor in fracture risk. In a study of 20 hyoid bones, primarily from females, Pollanen and Chiasson found that longer and more steeply sloped hyoid bones were more susceptible to fracture (14). This is in agreement with Mukhopadhyay, who did a prospective study of 100 cases of hanging and found that longer and wider hyoid bones were more susceptible to fracture (15).

Larynx

The larynx is located anterior to the third through sixth cervical vertebrae. It is composed of cartilages, ligamentous membranes, and muscles that are situated below the hyoid bone and above the trachea (3). Together, these structures work to facilitate breathing and sound production. The intrinsic muscles of the larynx include the cricothyroid, posterior cricoarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, thyroarytenoid, transverse arytenoid, oblique artenoid, and vocalis muscles (6). In addition to the muscles, there are nine cartilages (paired and unpaired) that form the larynx.

Viewed anteriorly, the thyroid cartilage is the largest laryngeal cartilage (Image 3). It has two laminae (dextra/sinistra) that are fused at the laryngeal prominence (“Adam's apple”), two superior horns (cornu superior) that extend from the superolateral margins of each laminae, and two inferior horns (cornu inferior) that extend from the inferolateral margins of each laminae. Inferior to the thyroid cartilage is the cricoid cartilage, a signet ring-shaped structure (Images 3 and 4). The two cartilages are connected via the cricothyroid membrane. The wider portion of the cricoid—the lamina—is located posteriorly while the narrow portion, the arch, is located anteriorly.

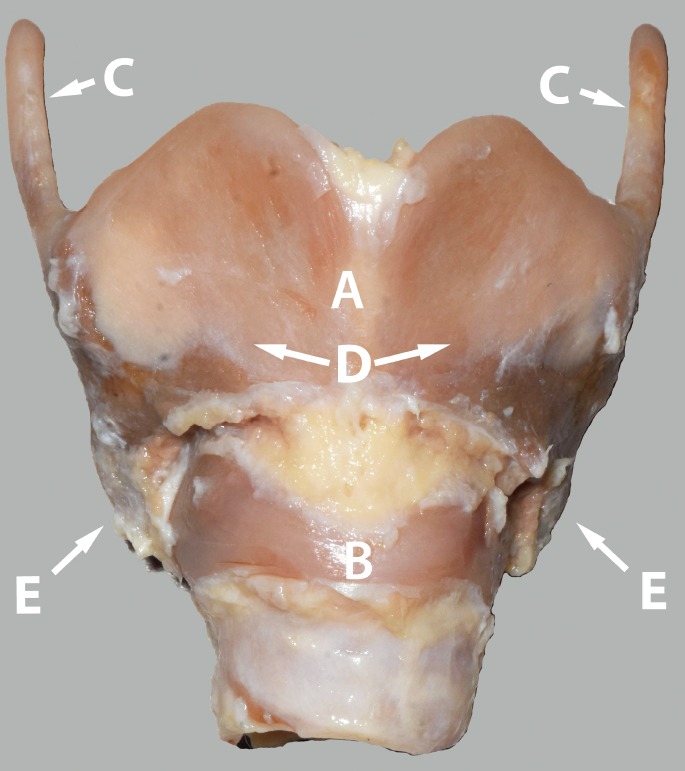

Image 3.

Anterior view of the articulated thyroid and cricoid cartilage. The perichondrium has been removed. A = thyroid cartilage, B = cricoid cartilage, C = superior horns of the thyroid cartilage, D = laminae of the thyroid cartilage, and E = inferior horns of the thyroid cartilage.

Image 4.

A lateral view of the thyroid-cricoid cartilage complex. Note that the structures are closely connected. The perichondrium has been removed.

The seven remaining laryngeal cartilages are best viewed from the posterior. The arytenoid cartilages are paired pyramid-shaped structures situated on the posterosuperior laminae of the cricoid cartilage. The paired corniculate cartilages are two small conical structures located at the apex of the arytenoid cartilages. The cuneiform cartilages are small, paired elongated structures that connect the arytenoid cartilage to the epiglottis. Finally, the epiglottis is a leaf-shaped cartilage that is connected to the thyroid cartilage by the thyroepiglottic ligament and to the hyoid by the hyoepiglottic ligament. In terms of trauma analysis, the arytenoid cartilages, cuneiform cartilages, and epiglottis are less important, likely due to their lack of susceptibility to fracture (4).

Embryologically, the laryngeal structures form from the 4th and 6th pharyngeal arches. This chondrification begins at the eighth embryonic week and by the end of the second trimester, they have acquired their neonatal form (3). Age-related ossification of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages has been well studied; however, the variation in ossification rates precludes this method as a good means of estimating age (16). A study done by Bockholdt et al. using 120 thyroid cartilages showed that high rates of fracture are observed in cases where ossification is incomplete while completely ossified cartilages had no macroscopic injuries (17). The same study demonstrated that in an isolated thyroid cartilage, the mean weight that a superior horn can sustain before fracturing is 3 kg (force = 28.5 N). In a study of 28 cases where the decedent was under the age of 18 years, Verma found seven cases of fractures, five cases of thyroid horn fractures, and two cases of hyoid bone fracture (18). Injuries in both bone and cartilage were not found in any of the cases.

Anatomical Anomalies

Anomalous laryngohyoid structures can result in erroneous diagnosis of trauma, whether acute or remote. The practitioner should be aware of what anomalies exist and how they may potentially affect normal functioning as well as trauma analysis.

Hyoid Anomalies

Anomalies of the hyoid bone involving differential development of the greater and lesser horns can result in the asymmetrical development of greater horns (8, 19) or agenesis of the lesser horn (8, 19,20). Atypical morphology can even include differences in shape of the hyoid bone. Klovning and Yursik reported on a nearly circumferential hyoid bone from a 28-year-old male who was difficult to intubate (21). Osseous extensions, possibly resulting from Eagle Syndrome (ossification of the stylohyoid ligament) or from unknown etiology, have also been reported (19, 20). Practitioners should be aware of such anomalies as they can affect not only medical intervention, but also medicolegal death investigations.

Laryngeal Anomalies

The presence of triticeal cartilages has been noted in studies addressing variations in the larynx. These cartilages are located within the thyrohyoid ligament, which connects the distal end of the greater horn of the hyoid and the superior thyroid horns. Di Nunno et al. noted that 30% of examined cases had the presence of unilateral or bilateral triticeal cartilages and Naimo et al. found it in 23% of examined cases (8, 22). When palpated, these cartilaginous bodies can appear to be a fractured superior thyroid horns (Image 5). Careful dissection is needed to investigate this finding. Sometimes abnormal congenital defects can result where the greater hyoid horn and superior thyroid horn become disconnected. An ossified hyothryoideal bridge may then be found later on in life (4). Congenital malformations can also affect the larynx. The presence of a laryngeal cleft, an opening along the posterior region of the larynx extending anywhere from the pharynx to the trachea, have been reported in individuals; however, the presence of the cleft anteriorly, suggests a history of neck trauma (19). Differential development of the superior thyroid horns that result in unilateral or bilateral agenesis have also been observed (19, 22,23)

Image 5.

A unilateral triticeal cartilage (black arrow). These can also occur bilaterally.

Trauma

Neck injuries observed in autopsy cases are typically the result of blunt force injuries due to sharp force trauma (24), athletic activities (25, 26), hanging (27, 28), falls from variable heights (29), vomiting (30), and strangulation (13). It is the purview of the forensic pathologist to determine the cause of death. The problem with this determination is that these closely tethered structures are subject to similar patterns of injury when different mechanisms are used. To further complicate matters, the incidence of hard tissue injury associated with a mechanism has been variably reported, therefore, making it difficult for the practitioner to interpret certain injuries. In a study of 1930 cases autopsied including all manners of death, Dunsby and Davison found fractures in the larynx or hyoid in only 78 cases (1). Pinto and Oleske found that out of 114 cases including all manners of death, only 50% had fractures in the larynx or hyoid (31). However, their sample was biased toward cases where a suspicion of fracture resulted in additional processing and examination. DiMaio looked at all cases of homicide due to asphyxia over a three-year period (32). He found that out of 133 cases, 48 cases were ligature deaths with 12% having laryngeal trauma and 41 cases were manual strangulation cases with over 66% of the cases having laryngeal trauma.

The main indicator of trauma in the larynx is the presence of hemorrhage. Macroscopic inspection of the neck structures allows identification of overt hemorrhage; however, several researchers have demonstrated utility in microscopic investigations as well (33–35). Rajs and Thiblin examined histological sections from 29 adult autopsy cases with nonartifactual superior thyroid horn fractures and 19 autopsy cases with artifactual fractures and found that the presence of occult hemorrhage can be used to identify nonartifactual fractures (34). Pollanen and McAuliff examined sagittal sections from 12 thyroid cartilages subjected to strangulation and found multifocal acute hemorrhages at the base of the superior horn, suggesting that the blood vessels can be disrupted during elastic deformation (33). Laryngeal microfractures have also been associated with intracartilaginous laryngeal hemorrhage, subepithelial laryngeal hemorrhage, and intralaryngeal muscular hemorrhage (36). Although a useful indicator, hemorrhage is not always present, particularly in cases involving children and adolescence, due to cartilage avascularity (37). Furthermore, some researchers have suggested that hemorrhage could be due to processing defects (37, 38). In addition, forensic pathologists may encounter cases where soft tissue is unavailable and the only structures remaining for assessment are the osseocartilaginous structures of the larygohyoid complex. Understanding the variety of causes that can result in fractures of these structures can help the forensic pathologist whittle down the list of possible candidate causes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary Table of Injured Structures Reported in the Literature Based on Cause of Death

| Cause | Hyoid Bone | Thyroid Cartilage | Cricoid Cartilage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging | Observed | Observed | *Observed |

| Strangulation | Observed | Observed | Observed |

| Falls | Observed | Observed | Not observed |

| Athletic activities | Observed | Not observed | Not observed |

| Self-vomiting | Observed | Not observed | Not observed |

| Therapeutic intervention | Observed | Observed | Not observed |

Observed in only one out of 2700 cases in the literature.

Hanging

Hanging is a condition where hyoid bone and/or laryngeal cartilage fractures have been observed. In a study of 189 cases of hanging, greater horn fractures of the hyoid bone were found in 2.7% and thyroid cartilage and superior thyroid horn fractures were found in 5.3% of cases (27). A literature review by Khokhlov of hangings demonstrated that the superior thyroid horns are the most commonly injured structure, with fractures usually located in the base or shaft of the horn (28). These fractures of the superior horn have a unilateral higher occurrence. Laminae were not typically injured in cases of hanging. The review also reported that cricoid fractures are unusual for hanging. In a retrospective study of 557 cases of suicidal hangings, Nikolić et al. found that the osseocartilaginous structures of the layrngohyoid complex were injured in approximately half the cases (39). Out of the injured cases, 45% had thyroid-only injuries, 26% had hyoid-only injuries, and 27% had both structures injured. These injuries were primarily seen in individual older than 30 years of age.

Strangulation

The majority of strangulation cases are homicidal in manner and they typically present with injuries to the largyngohyoid complex (Image 6). In an experimental study simulating manual strangulation, Lebreton-Chakour et al. found that a majority of the fractures were observed in the hyoid bone, at the synchondrosis or on the greater horns (13). In a small percentage of specimens, they observed a fracture through the body. They found that the grip strength of a healthy man or woman is sufficient to generate a fracture by direct contact. However, the reader should take note that this study was done with the hyoid bone embedded in resin; therefore, these results reflect the amount of force needed to fracture the hyoid bone only. When surrounded by muscle and other soft tissue, a greater force may be needed. Godin et al. did a retrospective study of 287 cases of suicidal hangings, homicidal hangings, and homicidal strangulations and compared their results to 21 published studies totaling 2700 suicidal hanging cases (40). They found that cricoid fractures were only observed in homicide strangulations (5-20%) and are therefore a potential indicator of homicide. Only one case out of the 2700 suicidal cases in the literature had a report of a cricoid fracture. Injuries due to homicides also tend to be more extensive, with the presence of more fractures and hemorrhage (41). The problem that a forensic pathologist may encounter is differentiating whether the osseocartilaginous injuries of the larygohyoid complex are consistent with hanging or with strangulation. Without other supporting evidence from surrounding soft tissue, this differentiation may not be possible. Caution is needed when relying solely on interpreting trauma to this structure when trying to establish a cause of death.

Image 6.

Fractured thyroid and cricoid cartilages from a homicide case involving asphyxia with neck compression. The black arrows indicate the fractured left superior thyroid horn and left anterior arch of the cricoid cartilage.

Falls

Fractures due to falls can complicate matters when assessing cause and manner of death because such injuries may raise suspicion of nonaccidental inflicted trauma. Furthermore, in cases of falls, fractures occur at a lower frequency than in cases of hanging or strangulation and therefore, are not necessarily associated with this mechanism. Laryngohyoid fractures due to falls can result from low heights (i.e., less than 3 m) (1, 29, 42, 43), as well as from high heights greater than 3 m (1, 44). These fractures can be unilateral or bilateral and involve the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage; however, the incidence of both structures being involved is low.

Athletic Activities

Fractures due to athletic activities are rare. Cutuk et al. report on two football players who sustained hyoid bone fractures resulting from direct impact to the anterior neck (25). Others have also reported similar injuries in lacrosse players, also due to direct impact (26, 45).

Miscellaneous

Hyoid bone fracture has been reported to possibly be associated with self-induced vomiting (30) and therapeutic intervention (19, 46). Hashimoto et al. state that fractures of the inferior thyroid horns are seen more commonly in resuscitation attempts (46).

Conclusion

Interpreting injuries to the osseocartilaginous structures of the laryngohyoid complex can be complicated. Anatomical variants not typically observed in the general population may result in an erroneous assessment of trauma. In addition, different causes of trauma may result in the same or similar pattern of injury, primarily because the basic mechanism is the same. The forensic pathologist must be aware of these confounding issues and should use all the information available from the surrounding soft tissue as well as the circumstances of the case when assessing the cause and manner of death.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The author has indicated that she does not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1).Dunsby A.M., Davison A.M. Causes of laryngeal cartilage and hyoid bone fractures found at postmortem. Med Sci Law. 2011. Apr; 51(2): 109–13. PMID: 21793475. 10.1258/msl.2010.010209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Gray H. Gray's anatomy: the classic collector's edition. New York: Bounty Books; 1977. 1248 p. [Google Scholar]

- 3).Scheurer L., Black S. Developmental juvenile osteology. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2000. 587 p. [Google Scholar]

- 4).Soerdjbalie-Maikoe V., van Rijn R.R. Embryology, normal anatomy, and imaging techniques of the hyoid and larynx with respect to forensic purposes: a review article. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2008; 4(2): 132–9. PMID: 19291485. 10.1007/s12024-008-9032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).MacDonald-Jankowski D.S. The synchondrosis between the greater horn and the body of the hyoid bone: a radiological assessment. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1990. Nov; 19(4): 171–2. PMID: 2097227. 10.1259/dmfr.194.2097227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Moore K.L., Dalley A.F. Clinically oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. 1164 p. [Google Scholar]

- 7).Reed M.H. Ossification of the hyoid bone during childhood. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1993. Aug; 44(4): 273–6. PMID: 8348355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Di Nunno N., Lombardo S., Costantinides F., di Nunno C. Anomalies and alterations of the hyoid-larynx complex in forensic radiographic studies. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004. Mar; 25(1): 14–9. PMID: 15075682. 10.1097/01.paf.0000113931.49721.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).D'Souza D.H., Harish S.S., Kiran J. Fusion in the hyoid bone: usefulness and implications. Med Sci Law. 2010. Oct; 50(4): 197–9. PMID: 21539286. 10.1258/msl.2010.010400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Fisher E., Austin D., Werner H.M. et al. Hyoid bone fusion and bone density across the lifespan: prediction of age and sex. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2016. Jun; 12(2): 146–57. PMID: 27114259. PMCID: PMC4859847. 10.1007/s12024-016-9769-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Pollanen M.S., Ubelaker D.H. Forensic significance of the polymorphism of hyoid bone shape. J Forensic Sci. 1997. Sep; 42(5): 890–2. PMID: 9304837. 10.1520/jfs14225j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Pollard J., Piercecchi-Marti M.D., Thollon L. et al. Mechanisms of hyoid bone fracture after modelling: evaluation of anthropological criteria defining two relevant models. Forensic Sci Int. 2011. Oct 10; 212(1-3): 274.e1–5. PMID: 21764532. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Lebreton-Chakour C., Godio-Raboutet Y., Torrents R. et al. Manual strangulation: experimental approach to the genesis of hyoid bone fractures. Forensic Sci Int. 2013. May 10; 228(1-3): 47–51. PMID: 23597739. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Pollanen M.S., Chiasson D.A. Fracture of the hyoid bone in strangulation: comparison of fractured and unfractured hyoids from victims of strangulation. J Forensic Sci. 1996. Jan; 41(1): 110–3. PMID: 8934706. 10.1520/jfs13904j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Mukhopadhyay P.P. Predictors of hyoid fractures in hanging: discriminant function analysis of morphometric variables. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2010. May; 12(3): 113–6. PMID: 20206574. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Garvin H.M. Ossification of laryngeal structures as indicators of age. J Forensic Sci. 2008. Sep; 53(5): 1023–7. PMID: 18624888. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Bockholdt B., Hempelmann M., Maxeiner H. Experimental investigations of fractures of the upper thyroid horns. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2003. Mar; 5 Suppl 1: S252–5. PMID: 12935603. 10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Verma S.K. Pediatric and adolescent strangulation deaths. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007. Feb; 14(2): 61–4. PMID: 17650549. 10.1016/j.jcfm.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Advenier A.S., De La Grandmaison G.L., Cavard S. et al. Laryngeal anomalies: pitfalls in adult forensic autopsies. Med Sci Law. 2014. Jan; 54(1): 1–7. PMID: 23804583. 10.1177/0025802413485731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Gok E., Kafa İM, Fedakar R. Unusual variation of the hyoid bone: bilateral absence of lesser cornua and abnormal bone attachment to the corpus. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012. Aug; 34(6): 567–9. PMID: 22116407. 10.1007/s00276-011-0908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Klovning J.J., Yursik B.K. A nearly circumferential hyoid bone. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007. May-Jun; 28(3): 194–5. PMID: 17499139. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Naimo P., O'Donnell C., Bassed R., Briggs C. The use of computed tomography in determining developmental changes, anomalies, and trauma of the thyroid cartilage. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2013. Sep; 9(3): 377–85. PMID: 23794193. 10.1007/s12024-013-9457-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Hejna P., Janík M., Urbanová P. Agenesis of the superior cornua of the thyroid cartilage: a rare variant of medicolegal importance. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015. Mar; 36(1): 10–2. PMID: 25376709. 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Özbilen Acar G., Tekin M., Çam O.H., Kaytanci E. Larynx, hypopharynx and mandible injury due to external penetrating neck injury. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013. May; 19(3): 271–3. PMID: 23720118. 10.5505/tjtes.2013.58259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Cutuk A., Bissel B., Schmidt P., Miller B. Isolated hyoid bone fractures in collegiate football players: a case series and review of the literature. Sports Health. 2012. Jan; 4(1): 51–6. PMID: 23016069. PMCID: PMC3435900. 10.1177/1941738111419963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).French C., Kelley R. Laryngeal fractures in lacrosse due to high speed ball impact. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013. Jul; 139(7): 735–8. PMID: 23868431. 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Jayaprakash S., Sreekumari K. Pattern of injuries to neck structures in hanging-an autopsy study. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012. Dec; 33(4): 395–9. PMID: 22922547. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3182662761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Khokhlov V.D. Trauma to the hyoid bone and laryngeal cartilages in hanging: review of forensic research series since 1856. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2015. Jan; 17(1): 17–23. PMID: 25456050. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Jehng Y.M., Lee F.T.T., Pai Y.C., Choi W.M. Hyoid bone fracture caused by blunt neck trauma. J Acute Med. 2012. Sep; 2(3): 83–4. 10.1016/j.jacme.2012.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30).White J.K., Carver J. Self-induced vomiting as a probable mechanism of an isolated hyoid bone fracture. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012. Jun; 33(2): 170–2. PMID: 20585227. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181eafe25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Pinto D.C., Oleske D. A quantitative assessment of peri-mortem blunt force trauma of the neck [Internet]. Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, 68th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2016. Feb 22-27; Las Vegas, NV. p. 857. [cited 2016 JJun 30]. Available from: http://www.aafs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016Proceedings.pdf.

- 32).DiMaio V.J. Homicidal asphyxia. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000. Mar; 21(1): 1–4. PMID: 10739219. 10.1097/00000433-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Pollanen M.S., McAuliffe D.N. Intra-cartilaginous laryngeal haemorrhages and strangulation. Forensic Sci Int. 1998. Apr 22; 93(1): 13–20. PMID: 9618907. 10.1016/s0379-0738(98)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Rajs J., Thiblin I. Histologic appearance of fractured thyroid cartilage and surrounding tissues. Forensic Sci Int. 2000. Dec 11; 114(3): 155–66. PMID: 11027868. 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Davison A.M., Williams E.J. Microscopic evidence of previous trauma to the hyoid bone in a homicide involving pressure to the neck. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2012. Sep; 8(3): 307–11. PMID: 22350822. 10.1007/s12024-012-9316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Pollanen M.S. A triad of laryngeal hemorrhages in strangulation: a report of eight cases. J Forensic Sci. 2000. May; 45(3): 614–8. PMID: 10855967. 10.1520/jfs14737j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Khokhlov V.D. [Forensic medical assessment of hemorrhages in hyaline cartilages of the larynx]. Sud Med Ekspert. 2003. Nov-Dec; 46(6): 9–13. Russian. PMID: 14689776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Fieguth A., Albrecht U.V., Bertolini J., Kleemann W.J. Intracartilaginous haemorrhagic lesions in strangulation? Int J Legal Med. 2003. Feb; 117(1): 10–3. PMID: 12592589. 10.1007/s00414-002-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Nikolić S., Zivković V., Babić D. et al. Hyoid-laryngeal fractures in hanging: where was the knot in the noose? Med Sci Law. 2011. Jan; 51(1): 21–5. PMID: 21595417. 10.1258/msl.2010.010016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Godin A., Kremer C., Sauvageau A. Fracture of the cricoid as a potential pointer to homicide. A 6-year retrospective study of neck structures fractures in hanging victims. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012. Mar; 33(1): 4–7. PMID: 22442828. 10.1097/paf.0b013e3181d3dc24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Maxeiner H., Bockholdt B. Homicidal and suicidal ligature strangulation–a comparison of the post-mortem findings. Forensic Sci Int. 2003. Oct 14; 137(1): 60–6. PMID: 14550616. 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Bux R., Padosch S.A., Ramsthaler F., Schmidt P.H. Laryngohyoid fractures after agonal falls: not always a certain sign of strangulation. Forensic Sci Int. 2006. Jan 27; 156(2-3): 219–22. PMID: 16024196. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Charlier P1, Coffy M., Grassin Delyle S. et al. Laryngohyoid and cervical vertebra lesions after a fall from a low height. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011. Sep; 32(3): 287–90. PMID: 21725226. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e318221ba8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).de la Grandmaison G.L., Krimi S., Durigon M. Frequency of laryngeal and hyoid bone trauma in nonhomicidal cases who died after a fall from a height. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2006. Mar; 27(1): 85–6. PMID: 16501357. 10.1097/01.paf.0000201104.10652.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Trinidade A., Shakeel M., Stickle B., Ah-See K.W. Laryngeal fracture caused by a lacrosse ball. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015. Nov; 25(11): 843–4. PMID: 26577976. http://dx.doi.org/11.2015/JCPSP.843844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Hashimoto Y., Moriya F., Furumiya J. Forensic aspects of complications resulting from cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2007. Mar; 9(2): 94–9. PMID: 17276125. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]