Abstract

Wars and armed conflicts by their very nature are cruel and ruthless. In the 17th century, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as the father of public international law, wrote in The Rights of War and Peace Book 3, Chapter 1:VI that “wars, for the attainment of their objects, it cannot be denied, must employ force and terror as their most proper agents.” A forensic pathologist can play a crucial role in armed conflicts because of the unique training that he or she receives, including examination of human remains to determine both the cause and manner of death, and discussing the mechanism of death. Although the obvious role, then, would be to perform exhumation autopsies in mass killings or genocides, being a physician, a forensic pathologist is also uniquely qualified to evaluate and document physical torture, use of excessive force, and use of chemical weapons, as well as violation of medical neutrality in armed conflicts based on prevailing laws and conventions.

Most of the investigations this author has conducted, including investigation of Rwanda and Bosnia genocides, violation of medical neutrality and use of excessive force in Bahrain and the Occupied West Bank and Gaza, searching for mass graves in post-Saddam Iraq, documenting mass graves in Bamiyan as well as Dash-t-Layli in Afghanistan after the defeat of the Taliban, and conducting local area capacity assessment in Libya after the fall of Colonel Gadhafi were all sponsored and logistically supported by nongovernmental organizations such as Physicians for Human Rights (USA).

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Forensic pathologist, Armed conflict, Violation of medical neutrality, Use of excessive force, Torture

Introduction

Violation of human rights in armed conflicts is pervasive throughout the world exacting a serious toll on physical and mental health as well as social well-being. This linkage between health and human rights has long been recognized. In 1986, the World Health Organization developed the most widely used modern definition of health: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely absence of disease or infirmity” (1). This was emphasized in the Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978), which described health as a “Social goal whose realization requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector” (2). Jonathan M. Mann et al. building on these earlier efforts promoted the idea that violations or lack of fulfillment of any and all human rights have negative effects on physical, mental, and social well-being, both in peacetime and particularly so in times of conflict and extreme political repression (3). They also expressed the notion that health and human rights act in synergy.

Discussion

Medical Neutrality and Use of Excessive Force

In armed conflicts, violation of medical neutrality and use of excessive force almost always go hand-in-hand. Investigating such violations in a hostile, wartorn environment may pose peril to a forensic pathologist, especially when the war-torn country cannot or is unwilling to guarantee security. Another peril is the carnage on the ground that may influence the investigator to take sides in the conflict. When a forensic pathologist falls into this trap, he or she ceases to be a neutral investigator and assumes the role of an advocate. During the 2014 invasion of Gaza, a group of physicians serving in Gaza published an editorial letter in the prestigious medical journal, The Lancet, describing “the massacre in Gaza,” which they claimed spared no one, including the disabled and sick in hospitals, children playing on the beach or on the roof top, along with wanton destruction of hospitals, clinics, ambulances, mosques, schools, and thousands of private homes (4). Whilst these observations may have been accurate, this group of physicians serving in war-torn Gaza were not investigators—they were humanitarians advocating cessation of hostility.

Medical Neutrality

The term “medical neutrality” refers to doctors' ethical duty as set forth by the World Medical Association (WMA) to prevent and limit suffering of patients in their care and a duty to practice medicine in a neutral way without fear or favor to those in need regardless of nationality, ethnicity, political affiliation, or other social division.

The killing and incarceration of health workers during conflicts is not new. Public health facilities are commonly selected as military targets, sometimes on the pretext that they shelter subversive elements. In Kosovo, health professionals were specifically targeted; in East Timor, the head of Caritas (which runs a critical health clinic) was killed, patients and doctors were intimidated, and health facilities were militarized. In occupied West Bank and Gaza during the Aqsa Intifada (Second Intifada) in 2000 and 2001, and again in the occupied West Bank in 2002 when the Israeli Defensive Forces (IDF) assaulted the refugee camp in Jenin, there were many documented instances of flagrant violation of medical neutrality by the IDF, who targeted ambulances claiming that they harbored “terrorists” or carried ammunition.

Some of the most egregious acts of violent aggressions against unarmed civilians and medical facilities have been carried out in the ongoing conflict in Syria. Since the conflict began in 2011, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have documented the killings of 679 medical personnel. Although almost all parties to the Syrian conflict are violating human rights and humanitarian law, the scope and scale of the government's assault on medical personnel and facilities are among the worst since the adoption of the modern Geneva Conventions (5).

In summary, medical neutrality comes down to the right of medical personnel, medical facilities, and the sick and wounded to stay untouched by the surrounding conflict. These rights, in turn, impose upon physicians the duty to stay neutral in a conflict. Physicians in the Bahraini conflict failed to maintain their neutrality and as a consequence, suffered incarceration.

Use of Excessive Force

The Geneva Conventions have been in existence for more than 65 years and are binding on everyone (6). Their most important feature is a set of rules for protecting civilians in the course of armed conflicts. They do not address the legitimacy of conflicts; rather, they say that even when the use of force is justified, there are limitations to its use. Indeed, that is their entire purpose, to place limitations on the use of military force. In any conflict, among other requirements, military authorities must avoid indiscriminate harm to civilians, excessive or disproportionate use of force in civilian areas, and must not interfere with medical services to the sick and wounded. The Geneva Conventions also distinguish between accidental or unavoidable civilian deaths, which are not prohibited, and civilian deaths and injuries that are a product of violations. Again, a forensic pathologist is uniquely qualified to render an opinion as to whether deaths of civilians, based on circumstances, scene findings, and autopsy findings were intentional or accidental and whether excessive force was employed.

Investigation of Assault on Medical Neutrality and Use of Excessive Force in Bahrain and Israel

Pearl Uprising of 2011 in Bahrain

Background

Bahrain is a constitutional monarchy with close ties to the United States. It is governed by a bicameral National Assembly (al-Jamiyh al-Watani) consisting of the Shura Council (Majlis Al- Shura) with 40 seats and the Council of Representatives (Majlis Al-Nuwab) with 40 seats. The 40 members of the Shura are appointed by the King. The Council of Representatives are elected by absolute majority vote in single-member constituencies to serve four-year terms. The referendum on National Action Charter was supported by an overwhelming majority in the February 14-15, 2001 election.

The political unrest in Bahrain is not a new phenomenon. The “1990s Uprising in Bahrain” was a rebellion in Bahrain between 1994 and 2000 in which leftists, liberals, and Shi'a Islamists joined forces. The event resulted in approximately 40 deaths and ended after Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa became the Emir of Bahrain in 1999 and promised change. A referendum in mid-February 2001 massively supported the National Action Charter as noted above.

The current political unrest, triggered by the events in Tunisia and Egypt, began on February 14, 2011. The protesters once again demonstrated and demanded social, economic, and political rights. Most of the protestors were Shi'a who felt politically disenfranchised by the ruling minority Sunni government. They selected February 14 as a day of protest to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the National Action Charter. Thousands of protestors converged on the Pearl Roundabout. On February 18, 2011, five people were killed when police raided the Pearl Roundabout protests early in the morning. As the unrest continued, troops from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates entered Bahrain on March 14, 2011 with the stated purpose of protecting essential facilities including oil and gas installations and financial institutions. The maneuver was carried out under the aegis of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Subsequently, soldiers and riot police expelled hundreds of protesters from the Pearl Roundabout, the landmark square in the capital city of Manama, using tear gas and armored vehicles.

Healthcare in Bahrain

Bahrain boasts a modern, technologically advanced, and comprehensive healthcare system with a large number of qualified Bahraini doctors, many of whom have studied abroad and returned home to practice. Full medical healthcare is available through both private and public systems. Public medical services are often free or subsidized. There is high demand for specialized medical services here and the latest medical and surgical procedures, such as transplants, are available. The Ministry of Health supervises all healthcare and pharmaceutical activities, and licenses all healthcare professionals. Existing healthcare facilities include ten full service private hospitals, staffed by Bahrainis and expatriate professionals; nine government hospitals including the flagship hospital, the Salmaniya Medical Complex (SMC) which houses two medical faculties; and 22 government health centers.

Various health care indices rank Bahrain high, for instance the infant mortality rate (IMR). The IMR indicates the number of deaths of babies less than one year of age per 1000 live births. The infant mortality rate correlates very strongly with, and is among the best predictors of, a country's level of health or development, and is a component of the physical quality of life index. The reported IMR for Bahrain is 7.3/1000 live births (2008) compared to 6.7/1000 live births for the United States (2006) (7). Finally, 100% of the population has access to health services and over 97.5% of infants are immunized.

Salmaniya Medical Complex, the hospital that was militarized and the focus of violation of medical neutrality, is an advanced secondary and tertiary health care system, geared to meet the needs of the citizens and residents of Bahrain in the most effective and efficient manner possible and at the highest level of quality within its available resources. Additionally, SMC functions as a teaching and research center for health professionals and houses two medical schools including the College of Health Science and the Arabian Gulf University. Salmaniya Medical Complex lies in the heart of the busy metropolitan city of Manama, within two to three kilometers of the Pearl Roundabout, the site of demonstrations and crackdown by security forces.

Methodology

Over a period of seven days, a team comprised of the author and an experienced investigator from Physicians for Human Rights (USA) conducted 47 interviews with patients, physicians, nurses, medical technicians, and other eyewitnesses to human rights violations, and when made available, reviewed medical records. The qualitative domains of the interview instrument were developed by adapting health and rights instruments used in similar settings where violations of medical neutrality have occurred. Interviews were conducted in English and Arabic and to protect the informants, identifying information was removed from the interview record. Data gathered were analyzed using qualitative methods and augmented with a literature and lay media review. The actual medical interviews, review of medical charts, as well as examination and documentation of injuries were conducted by the author, whereas the scene investigations, where necessary, were conducted and documented by the investigator.

The weakness of this study was the short time frame in Bahrain during which the study was conducted thereby precluding full analysis of the impact on the health system. Additionally, restricted access to health facilities and medical personnel also hampered a comprehensive account of all human rights violations. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study produced sufficient firm data to clearly document violation of medical neutrality as well as use of excessive force against a mostly unarmed civilian population.

Findings

Findings included indiscriminate use of CS gas (ortho-chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile) in dense populated areas, use of lethal force against mostly unarmed civilians, as well as arbitrary arrest and incarceration of health professionals.

During the initial stages of civil disobedience, police, security forces, and the army in Bahrain (henceforth “Bahraini Security Forces”) used water cannons and nonlethal lachrymatory agents to control riots. Tear gas is a nonspecific term for any chemical that is used to cause temporary incapacitation through irritation of the eyes and or respiratory system. It is usually fired in canisters that heat up spewing out a gas cloud at a steady rate. The chemical effect has a rapid onset and very short half-life, no more than 15 minutes. In Bahrain, CS gas was deployed in almost all cases and many protestors suffered acute respiratory distress. CS gas was also used in close, dense residential areas in many Shi'a villages and, according to eyewitnesses interviewed and medical charts reviewed, the elderly as well as the young suffered acute and sometimes severe respiratory distress syndrome.

A registered nurse (name withheld) assigned to the Outpatient Department at SMC where she helped with triage observed many patients who had been exposed to CS gas. Many of these patients exhibited acute respiratory distress with shortness of breath, sensation of choking, disorientation, hysterical behavior, as well as sensation of burning. She also observed many patients with first-degree burns of the face, especially the zygomatic areas where she applied diluted Amoxel (liquid antacid) and prescribed Volatern (Diclofenac – a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent) for pain management. Many of these patients also exhibited signs of conjunctivitis. In addition, she observed two patients with convulsions, one of whom was in the postictal stage, nonresponsive, and frothing at the mouth. Both these patients received atropine and responded well. Atropine blocks the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors and, hence, serves well as a treatment for poisoning by organophosphate insecticides and nerve gases, such as Tabun (GA), Sarin (GB), Soman (GD), and VX. It remains unknown what chemical agents Bahraini Security Forces deployed for crowd control against their unarmed civilian population. In this context, deployment of CS gas and other chemical agents are prohibited under the Geneva Convention. As the protests escalated, Bahraini Security Forces began deploying lethal force including high velocity weapons, shotguns, and other firearms. A 19-year-old Bahraini protestor from Karzakan was in the frontline at Pearl Roundabout, facing the police from a distance of 20 meters. The riot police started to deploy tear gas, rubber bullets, and then live ammunition (shotguns). Several protestors were wounded. Those that failed to escape were physically assaulted, with the police using batons and butts of guns. Our witness sustained a shotgun injury with pellet wounds of the left medial arm and left posterior leg (Image 1).

Image 1.

Distant range entry shotgun wound of left posterior leg with large entry defect.

Ghada, a resident of the village of Karzakan along the Western coast of Bahrain island and fourth year nursing student, was on nursing duty at SMC where she witnessed two patients with gunshot wounds of the head, four other patients on ventilators due to firearm injuries, and two patients with eye injury due to shotgun blast (Image 2).

Image 2.

Gunshot wound of head in the emergency department (Salmaniya Medical Complex).

It is a generally accepted principle that when the use of lethal force cannot be avoided, the force should be proportionate. The use of firearms is considered an extreme measure or as a last resort, and under the Geneva Convention may be deployed when there is imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. Based on many eyewitness accounts and extensive interviews, the Bahraini Security Forces throughout this crisis faced no imminent threat to their lives primarily because the protestors had no access to any lethal weapons.

This investigation documented many incidences of arbitrary arrests and incarceration of health professionals. Armed security forces abducted Dr. Ali El-Ekri from the operating room while he was performing surgery at SMC on March 17, 2001. The whereabouts of Dr. Ekri remains unknown. In another incidence, police and masked men in civilian clothes stormed the home of Dr. Abdul Khaliq al-Oraibi on April 1, 2001. The security forces dragged him out of bed, handcuffed, and blindfolded him. Our investigation also uncovered other violations of medical neutrality including physical abuse of six Shi'a physicians at SMC, government security forces stealing ambulances and posing as medics to arrest injured protestors, the militarization of hospitals and clinics that obstruct medical care, and promoting fear of arrest thereby preventing patients from seeking urgent medical treatment.

Israel's Operation Defensive Shield 2002

Background

Israel operates under a parliamentary system as a democratic republic with universal suffrage. It, too, has close ties with the United States. A member of Knesset parliament (Knesset) supported by a parliamentary majority becomes the prime minister—usually this is the chair of the largest party. The prime minister is the head of government and head of the cabinet. Israel is governed by a 120-member parliament.

Israel's Operation Defensive Shield began on March 19, 2002 with assault first on the city of Ramallah, followed by Tulkarem and Qalqilya on April 1, Bethlehem on April 2, and finally Jenin and Nablus on April 3. During the assault on Jenin, the Jenin refugee camp bore most of the brunt with many homes destroyed and scores of Palestinians killed and injured. According to Israeli sources, the camp was a military target mainly because it housed some 200 hard-core militants including those from Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. There were also allegations that attributed 23 suicide bombings and six attempted bombings to Palestinians from the camp during the Second Intifada (8).

Jenin is an ancient city, situated at the foot of the rugged northernmost hills and along the southern edge of the Jezreel Valley in the Occupied West Bank. It houses the regional administrative complex for the Jenin Governorate and is a major commercial and healthcare center for the surrounding towns. The estimated population of Jenin in 2002 was 35 000. The Jenin Governmental Hospital is the only governmental hospital in Jenin. With a capacity of 123 beds, the hospital, then, served a large part of the northern West Bank, particularly the Tubas and Jenin areas. It included a pediatric and neonatal wing, a maternity ward, departments of internal medicine and surgery, a regional dialysis center, and an intensive care unit.

The Jenin refugee camp is one of 18 refugee camps in the West Bank. The original camp was built in 1948 at the time of partition and subsequently rebuilt in 1953 by United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) on 0.423 square kilometers leased from the government of Jordan (9). The inhabitants of the camp are the original refugees who were displaced or who fled in 1948 from Carmel Mountains, including the now Israeli city of Haifa at the time of partition, and who were never allowed to return. Like all other Palestinian refugee camps in West Bank and throughout Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, this camp was designated as a temporary settlement, but over the years has become a permanent residence for displaced Palestinians from the Haifa region along with their progeny as well as those internally displaced from Gaza and Tulkarem. In April 2002, the camp was home to 13 055 UNRWA registered Palestinian refugees.

Early reports published by Human Rights Watch as well as major Western news media and based on local eyewitness accounts suggested widespread destruction of the camp with high mortality (10). Prompted by these reports, the United Nations (UN) Security Council on April 19, 2002 adopted resolution 1405, a unanimous resolution that was supported by the Bush Administration. Resolution 1405 expressed concern of the dire humanitarian situation of the Palestinian civilian population in the Jenin refugee camp and called upon Israel to lift restrictions imposed on the operations of humanitarian organizations including the International Committee on Red Cross and UNRWA for Palestine in the Near East (11). It also required the Secretary General to develop accurate information regarding the events in the Jenin refugee camp.

As part of this investigation as set forth in UN Security Council Resolution 1405, and in support of UN High Commission for Human Rights, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR-USA) established an assessment team with a mandate to provide more accurate preliminary data to support a formal investigation by the UN. The team was composed of the author; William Haglund, PhD, Director of PHR-USA's International Forensic Program; and Col. Brenda Hollis (United States Air Force - retired), an attorney and senior investigative and legal consultant to the Institute for International Criminal Investigations.

Methodology

Over a period of five days, the team inspected and documented the destruction of many homes and interviewed local residents of the camp, many of whom were injured and being treated in Jenin General Hospital. The team also toured the hospital; interviewed physicians, interns, and nurses; visited patients in the intensive care unit; reviewed 102 medical records including radiographs; and performed two forensic autopsies. Interviews and examination of the injured in the hospital; review of radiographs and medical records; and interviews of physicians, nurses, and interns were conducted by the forensic pathologists in addition to the performance of two autopsies. The rest of the team members inspected and documented the destruction of the camp by IDF.

As in the case of Bahrain, the qualitative domains of the interview instrument were developed by adapting health and rights instruments in similar settings where violations of medical neutrality and use of excessive force against mostly unarmed civilians have occurred. Once again, for protection of key informants, all identifying information was removed from the interview record. Interviews were conducted in English and Arabic. Interview data were analyzed using qualitative methods and were augmented with literature and lay media review. The team also faced hardship imposed by the Israeli government. The author, who was first to arrive on April 21, 2002 at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, was denied entry and confined to a holding cell for deportation to the US. Eventually, through legal intervention, he was allowed entry into Israel. There were other obstacles and perils. The major thoroughfare connecting Jerusalem to Jenin is Route 60, or what is dubbed as the “Way of Patriarchs,” was blocked by IDF. Route 60 is a south-north intercity road that stretches from Beersheba through Jerusalem, across the Occupied West Bank, passing through Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin, and ending in Nazareth. After consultation with local residents in East Jerusalem, the team learned that the Israeli government had placed a total blockade on Jenin from all southerly routes and that the only way to enter Jenin was by scaling a six-foot barbed wire fence erected by Israel along the 1949 Armistice Line. The team was guided and assisted by local residents in Jerusalem to travel by a taxi driven by a trusted Israeli Arab and to jump the fence at the eastern outskirts of Israeli Arab town of Umm al Fahm, which was apparently poorly patrolled.

On Monday, April 22, 2002, in the early morning hours, the team successfully jumped the fence then walked across a meadow for approximately 1 km and took shelter behind a hill from where a Palestinian taxi from the Occupied West Bank picked them up. The distance to Jenin was merely 18.5 km through the town of Anin and then along Route 596 to Jenin.

The weakness of this study was the short time frame in Jenin during which the study was conducted, thereby precluding full analysis of the extensive physical damage done to the Jenin refugee camp and assault on the health system by IDF. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study produced sufficient firm data to clearly document violation of medical neutrality as well as use of excessive force against a mostly unarmed civilian population.

Findings

The team had two objectives. The first objective was to evaluate the possible use of excessive force by examining the wounded patients in the hospital, establishing their injury patterns, and determining whether medical care was provided in a timely fashion. The second objective was to evaluate breach of medical neutrality.

Nearly 95% of injuries during the IDF incursions into Jenin and the Jenin refugee camp were treated or examined at the Jenin Governmental Hospital. The hospital treated a total of 102 patients between April 3 and 22, 2002. Although there were widespread allegations made by Palestinian Authority that over 500 Palestinians were killed, the PHR-USA team, as of April 23, documented 45 fatalities, although this number was expected to rise as more bodies were being recovered from the rubble of collapsed homes and buildings (Image 3).

Image 3.

Jenin refugee camp – extensive destruction of camp.

Overall, based on hospital records reviewed and patients interviewed, over 33% of the patients admitted were women, children under 15 years, and men over 50 years with life threatening trauma. Children under 15 years and women and men over the age of 50 accounted for nearly 38% of all reported fatalities. One out of three reported fatalities were due to gunshot wounds, with vast majority sustaining fatal wounds of the head, or head and upper torso, by high velocity weapons (Image 4). The author was also able to verify by interviewing the injured, reviewing the medical records, interviewing other eye witnesses, as well as performing actual scene visits of the partially demolished homes, that several of those injured were either shot by IDF snipers or by IDF soldiers from helicopter gunships.

Image 4.

Child with high velocity gunshot wound of arm (post amputation) at hospital.

Additionally, shrapnel injuries and blast injuries accounted for nearly 32% of all admissions. Thirteen patients who were admitted to the hospital with extensive blunt force trauma provided sworn testimony that they were subjected to advanced interrogation techniques by IDF soldiers.

Eleven percent of the total reported fatalities were due to crush injuries in addition to a 55-year-old male crushed by a tank in the township of Jenin. Eyewitness testimony provided evidence that the decedent was in clear view of the tank when he was run over.

The author also performed two postmortem examinations that included an unidentified male with approximate age between 18 and 23 years and an older person whose government issued identification card indicated he was 56 years of age. Their bodies were recovered under the rubble of demolished buildings. Both had died of crush injuries. Age estimation was provided by Dr. Haglund, a forensic anthropologist.

Finally, some patients were unable to receive timely access to medical care, regardless of the severity of their injury, simply because of the tight closure of the camp by IDF. In some instances, the injured reported that they were unable to access medical assistance as much as seven days after sustaining severe debilitating firearm injury. Survey of the patients still housed at Jenin Governmental Hospital reported delays ranging from three to seven days.

There was significant evidence to support the allegation that the IDF flagrantly violated medical neutrality. Multiple interviews of patients and hospital staff alleged that IDF fired randomly at the hospital from a building commandeered across the street causing serious damage to the hospital facade and medical staff rooms, as well as causing panic. Firearm damage caused to the hospital by this random shooting was verified by actual site visit. This author documented damage to the glass windows and bullet holes in the interior walls and doors. On inspection of the damage and scene reconstruction, it was very obvious that the shots were fired from the commandeered building across the street as alleged by the eyewitnesses.

The team also confirmed that one of the two ambulances (Image 5) and one patient transport vehicle were crushed by IDF, who also downed power lines and smashed the hospital sewer lines at the onset of the Jenin refugee camp incursion thereby paralyzing the hospital during the initial stage.

Image 5.

Ambulance rendered inoperable by an Israeli Defensive Forces tank.

Aftermath

On Monday April 22, 2002, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan announced the names of his team that would set out as fast as possible to “develop accurate information regarding recent events in the Jenin refugee camp” in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1405 adopted three days earlier (11). The team consisted of former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari; Cornelio Sommaruga, former president of the International Committee of the Red Cross; and Sadako Ogata, the former UN high commissioner for refugees who was Japan's special envoy on Afghan reconstruction. The team, however, was never deployed because of objections raised by Foreign Minister Shimon Perez that it lacked neutrality as well as military expertise to conduct such an investigation (12).

Mass Graves and Genocide

Mass Graves

Scientific investigation of mass graves, especially in the setting of crimes against humanity as well as genocide, requires application of principles in forensic science with a multidisciplinary strategy supported by appropriate protocols and operating procedures. Although the crime of genocide is a type of crime against humanity, it differs in that in genocide there is a specific intent to exterminate a protected group (in whole or in part) while crimes against humanity require the civilian population to be targeted as part of a widespread or systemic attack, such as in the current Syrian crisis.

Many of the sites of mass graves are in war-torn countries with poor medical support, frequently lacking running water and electricity, and subject to security risks. Sound and adequate assessment requires not only inclusion of both historic as well as political and legal context, but also contexts in which the bodies were disposed in a mass grave; evidence in the grave; osteology; anthropomorphic assessment including estimates of age, stature, gender, and race where appropriate; dental and DNA evidence supporting a scientific identification where possible; assessment and documentation of trauma; inclusion of any postmortem scientific lab evaluation such as firearm and tool-mark examination; and certification of both cause and manner of death. It is generally acknowledged that bodies in mass graves even where the precise cause of death cannot be established result from crimes against humanity and as such are all homicide.

Genocide

Genocide is a value-laden word and does not include killings in the setting of a war or border skirmishes. It was Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-born adviser to the United States War Ministry during World War II, who coined the word “genocide,” constructed from the Greek “genos” (race or tribe) and the Latin suffix “cide” (to kill). According to Lemkin, genocide signifies “the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group” and implies the existence of a coordinated plan, aimed at extermination, to be put into effect against individuals chosen as victims exclusively because they are members of the target group (13). The extreme violence, mass killings, and atrocities committed against the Tutsi minorities clearly represent genocide in the fullest sense, although not to the scale of holocaust in World War II.

The concept of genocide first appeared in the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg) Judgment of September 30 and October 1, 1946, and later the prohibition of genocide was recognized by the General Assembly of the UN as a principle of international law. The crime of genocide is now considered part of international customary law and a norm of jus cogens. The twentieth century witnessed many atrocities that could be classified as genocide, although all of these were not systematically investigated using scientific tools. These include Bosnia-Herzegovina between 1992-1995 with estimated deaths of 200 000 Bosnians by Serbian forces, the Rwanda genocide of 1994 with an estimated 800 000 Tutsi killed by Hutu militiamen, killings by Pol Pot in Cambodia from 1975-1979 with an estimated 2 000 000 deaths, and the Holocaust by Nazi Germany from 1938-1945 with an estimated 6 000 000 deaths. Additionally, there are allegations and historic data to support that as many as 1 500 000 Armenians were killed by the Ottoman army from 1915-1918.

Background of Rwanda Genocide

The ethnic violence in Rwanda is primarily rooted in two groups, the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi. Tutsi had dominated the political landscape during the colonial period. Historically, the Hutus were cultivators and Tutsis were herdsmen, although there are claims that Hutu and Twa, the third ethnic group in Rwanda, were original inhabitants in Rwanda, and that Tutsi had migrated from the Nile region and horn of Africa. Germany was the first European country to colonize the area that is now Rwanda from 1885 to 1919, which was later turned over to Belgium by the League of Nations as a spoil of war after World War I and by the UN in 1945. Belgium continued to administer Rwanda until its independence in 1961. During the colonial days, Tutsis were favored and thus became the ruling class and ruled through monarchy. Independence changed the landscape when Hutu, who were the majority, became the ruling class.

Genocide in Rwanda began on April 6, 1994 when an airplane carrying President Juvénal Habyarimana along with the Burundian Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down in the capital city of Kigale in Rwanda. Habyarimana was a Hutu and was the President of the Republic of Rwanda from 1973 until his assassination. During his 20-year leadership, he favored his own ethnic group, the Hutus, against the Tutsi. His assassination ignited ethnic tensions in the region and helped spark the Rwandan Genocide.

From April to July 1994, members of the Hutu ethnic majority murdered, by some estimates, as many as 800 000 people, mostly of the Tutsi minority. The killing spree, which began in the capital of Kigali, and spread throughout the country with staggering speed and brutality, as ordinary citizens were incited by local officials and the Hutu Power government to take up arms against their neighbors. The killings finally ended when Tutsi-led Rwandese Patriotic Front gained control of the country through a military offensive in early July 1994.

Pre-exhumation assessment of the genocide by our forensic team identified hundreds of potential sites and graves to investigate in Rwanda. Our attention was directed to a mass grave near the Roman Catholic church and Home St. Jean in the parish of Kibuye, above Lake Kivu in the northwest of the country. The killings here were instigated by the parish's former prefect, Clément Kayishema. From April 8-17, 1994, Hutu officials throughout the parish of Kibuye directed Tutsi civilians to aggregate in Roman Catholic churches, which they dubbed as “safe havens.” On April 17 and 18, 1994, the complex was surrounded by Hutu extremists and interhamwe, a paramilitary organization which enjoyed backing of the Hutuled government in Rwanda leading up to and during the genocide, and the Tutsi who had gathered in this “safe haven” were brutally attacked. In the mayhem that followed, the Tutsi were clubbed and chopped to death. By all accords, unlike the Srebrenica killings of 7000 Bosnians in July 1995 by Serbian forces, this was dubbed as “low tech” genocide.

The killings in the parish of Kibuye were investigated in connection with the indictment of the parish's former prefect, Clément Kayishema, a trained medical doctor whom the Trial Chamber II of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda established by the UN Security Council eventually sentenced to life in prison for the crime of genocide on May 21, 1999. This author testified in the criminal trial of Clément Kayishema in Arusha, Tanzania in March-April 1998.

Methodology

The forensic team adopted a multidiscipline protocol based on past experiences in Central and South America and Asia, and enlisted archeologists to assist in locating and excavating the actual site. The planning, site preparation, area location, site location, site confirmation, site excavation, and recovery of remains from the mass grave, as well as procuring graveside evidence, was assigned to anthropologists. It was anticipated that comingling of bodies would pose a special challenge and, hence, the process of actual recovery was carefully and methodically carried out. Written protocols were established to standardize the forensic evaluation, which entailed radiographic documentation of injury pattern and presence of foreign bodies such as bullets in the remains; anthropomorphic assessment including sex, age, and stature assessment as well as reconstruction of osseous trauma when warranted by the anthropologists; postmortem examination by forensic pathologists, which would include documentation of injury by photographs and diagrams as well as collection and preservation of evidence by forensic pathologists.

The protocols also allowed the forensic pathologists to predict whether the “injury” present on the bones was due to grave artifact generated at the time of initial burial or secondary to the excavation process, although there are times when it is impossible to tell. Presence of antemortem trauma needed to be evaluated and a predictive value applied (i.e., whether the fracture played a role in the actual causation of death). A person does not die because of fracture alone, but because such an injury is associated with internal trauma, hemorrhagic shock, or medical complications resulting from fracture. In the case of firearm injuries, the forensic pathologist would attempt to establish whether the injury observed on a bone is an entry or an exit wound, whether the firearm was low-velocity or high-velocity, how many times a person was shot, the sequence of shots fired if possible, the range of fire, and whether a gunshot wound was the cause of death, and if so, how rapidly the death ensued. In decomposed or partially skeletonized bodies, range determination may be impossible. Furthermore, location of a firearm injury or blunt force trauma may allow the pathologist to predict how such an injury may have occurred, whether it was a consequence of combat, homicidal killing, an execution, or a stray shot. The issue of targeted versus ricochet shot became a point of dispute in the investigation of the death of an 8-year-old Mayan child, Santiago Pop “Tut”, shot in the head by Guatemala Special Forces on October 5, 1995. An autopsy performed in Guatemala by the author proved that it was a targeted shot of the head. Finally, at times, there are cut marks on the bones or stabbing injuries. Assessment must be made to establish whether the cut or stab injury present could be due to “torture,” represented the underlying cause of death, or due to secondary postmortem dismembering of the body.

Additionally, there were surface bodies located along the slopes between the shores of Lake Kivu and the promontory. Processing consisted of denuding the immediate vicinity of vegetation, searching for additional skeletal material, delineating individual bones, and noting their relative scatter and associates. This task was assigned to the anthropologists. In the majority of instances, assemblage of bones rested in relative anatomical order with minimum scattering. Many of the remains were, however, incomplete, which probably was due to five taphonomic influences including 1) consumption and scattering by scavenging animals, 2) scattering and burial through agricultural activity, 3) disturbance by local foot traffic, 4) down-slope movement assisted by gravity and rain water, and 5) incomplete collection and burial by local residents. A total of 39 skeletal assemblages representing individuals and 14 collections of bones not attributed to any specific individuals were collected. The assessment of trauma was performed by forensic pathologists.

There were 17 forensic examiners including forensic pathologists, forensic anthropologists, radiologists, and archeologists who volunteered to do the work on the site, the largest exhumation of its kind since World War II. They came from the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, and South America. The team also included support personnel who set up a large bladder to store fresh water, hooked up diesel operated generators to provide electricity, set up an X-ray machine and a dark room to process X-ray films, as well as portable showers and toilets, and perform duties of evidence custodian. The church, with its surrounding area, was converted to examination areas and an inflatable tent was set up for the autopsies (Figure 1). Twenty-four hour security for the church, grave, and areas of examination was provided by a contingent of UN troops. Finally, a generous perimeter of concertina wire was established to close off the area and a log was maintained to record visitors to the site. The team adopted a three-phase approach to exhume the mass grave and perform the forensic examination.

Figure 1.

Church complex and site of mass grave.

Image courtesy of Dr. William Haglund.

Phase 1: This phase began on December 17, 1995 and lasted two weeks, during which a team of archaeologists documented the site of the mass grave, created a small-scale topographic map of the site area, and photographically documented evidence in the buildings adjacent to the mass grave including the church. The grave, which was subsequently opened, measured 15.25 m by 13.7 m with a surface area exceeding 210 m2.

Phase 2: This phase also lasted two weeks during which 39 discrete surface skeletal assemblages were recovered around the church complex, as well as 14 collections of bones not attributed to any specific individual were collected by forensic anthropologists (Image 6). Their composition ranged from complete individuals to isolated bones. Many of the bones were dispersed. Dispersion was attributed to one or more of the five taphonomic influences listed previously.

Image 6.

Scatter of surface bodies near the church complex.

Phase 3: This phase overlapped with Phase 2 and continued until February 22, 1996. During this phase, excavation of graves, recovery of bodies, and examination of the bodies by forensic pathologists took place.

Findings

There were 39 surface bodies recovered and 454 bodies exhumed from the mass grave (Grave KB-G1). All the bodies were radiographed and photographed and those from the mass grave autopsied.

All the exhumed bodies depicted advanced states of postmortem decomposition with putrefactive changes as well as areas of mummification and adipocere formation. Of these, 30% were male (n = 135), 45% female (n = 205), and 25% with undefined gender (n = 114). Over 38% (n = 174) were children under the age of 16 years (Tables 1 and 2). The two predominate patterns of injuries included blunt force trauma and sharp force injuries; 63% (n = 288) of the victims were clubbed to death and 9.9% (n= 45) sustained sharp force trauma (Table 3).

Table 1:

Age and Sex Distribution for Surface Bodies on the Slopes of Lake Kivu

| Age Range (years) | Sex |

Total | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Unknown | |||

| 0–10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 30.7% |

| 11–15 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| 16–25 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 61.7% |

| 26–35 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | |

| 36–45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 45+ | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| >18 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | 12 | 6 | 21 | 39 | 100% |

| Percentage | 30.7% | 15.3% | 54% | ||

Table 2:

Age and Sex Distribution for Grave KB-G1

| Age Range (years) | Sex |

Total | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Unknown | |||

| 0–10 | 11 | 20 | 84 | 115 | 38.3% |

| 11–15 | 18 | 19 | 22 | 59 | |

| 16–25 | 29 | 56 | 6 | 91 | 61.7% |

| 26–35 | 31 | 34 | 0 | 65 | |

| 36–45 | 19 | 28 | 0 | 47 | |

| 45+ | 27 | 46 | 0 | 73 | |

| >18 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Total | 135 | 205 | 114 | 454 | 100% |

| Percentage | 29.7% | 45.1% | 25.2% | ||

Table 3:

Type of Trauma Attributed to Cause of Death for Grave KB-G1

| Type of Trauma | Number of Victims | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blunt Force Trauma | 288 | 63.4% | |

| Sharp Force Trauma | 45 | 9.9% | |

| Sharp/Blunt Force Trauma | 9 | ||

| Miscellaneous | Penetrating Trauma | 2 | |

| Shrapnel Wound | 1 | ||

| Gunshot Wound | 1 | ||

| Undetermined | Insufficient Remains | 43 | 24% |

| No Trauma Observed | 66 | ||

| Total | 454 |

Blunt force trauma, mostly of the head, was the most significant cause of death of individuals examined including those bodies recovered from the surface and from the mass grave. The patterns of injuries were typical of one or more severe blows, sometimes with multiple points of impact, and were inconsistent with accidental injuries. Many such skulls presented depressed skull fractures across suture lines often with fragmentation.

Sharp force trauma was all caused by machetes. A machete is a large broad knife that is commonly used in many parts of the world, especially in rural agricultural areas as a tool for harvesting. It has also been used as a weapon of convenience during altercations. In the Caribbean and Africa, machetes, known as “Panga”, are either straight bladed or curved. They are generally wide and weighted to ensure enough chopping power. Machetes cause nonmissile, penetrating lesions with impact velocity of less than 100 m/s, causing injury by laceration and maceration (14).

Many of the victims were struck on the head with deep cutting wounds, often with associated linear radiating skull fractures extending from the edges of the wound. Some cutting wounds were altered or obscured by subsequent blunt force trauma or postmortem damage, however, in many cases, the straight, linear, nonbeveled appearance of these injuries was obvious on examination. Whilst such injuries were easily identified when inflicted on head or chest wall, deep cutting or slashing wounds of the neck or abdomen would have produced fatal injuries undetected by skeletal remains. Combined sharp force and blunt force trauma were observed in only 20% of the cases (n = 9).

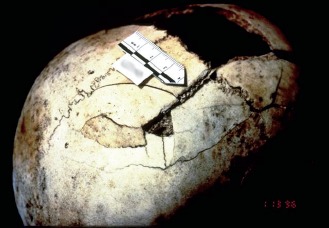

The pattern of injury allowed prediction of whether the sharp force trauma was due to a straight blade Panga or a curved (sickle-shaped) Panga Image 7. Image 8 depicts a patterned machete wound with a curved blade in this male with an estimated age of 20 to 26 years. There is a linear, full-thickness, incised wound measuring 5 cm primarily of the right parietal bone extending to the coronal suture. There is a triangular defect along the posterior region caused by the curved machete tip along with surrounding radiating comminuted fractures. The decedent also presented with a collapsed frontal bone due to blunt force trauma.

Image 7.

Panga with curved blade.

Image 8.

Panga head wound.

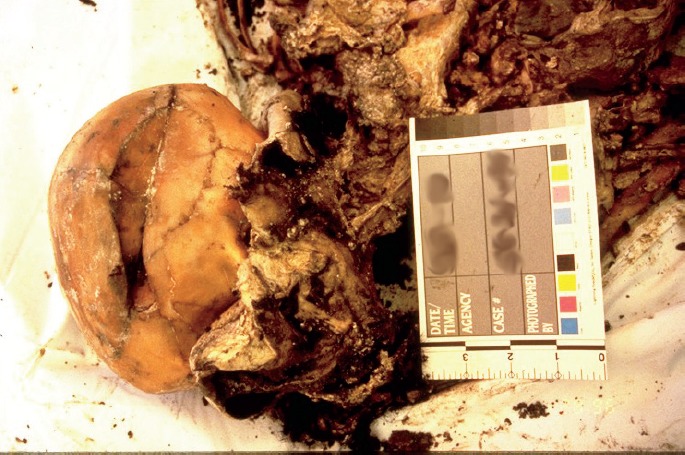

In Image 9, this female child with estimated age of 8 to 13 years sustained one massive blow to the left side of the cranium by a straight-blade Panga causing a linear, 12 cm long, full-thickness calvarial incised wound extending from the frontal scalp to the occipital region with prominent surrounding depressed fractures measuring 13 × 2 cm. Additionally, there were associated radiating fractures across the parietal bone and arrested by the sagittal suture with diastatic fractures of both squamosal and sagittal sutures.

Image 9.

Sharp force trauma of head with straight-bladed Panga.

Finally, there are relatively few bodies that showed defensive wounds of the hands or arms, although identification of merely soft tissue defensive wounds was impossible because of the state of postmortem decomposition. Lack of sharp force or blunt osseous trauma of hands and arms is indicative of a noncombat situation. Additionally, there were several cases with cutting wounds of the posterior distal aspect of the tibiae and/or fibulae, including one case with complete amputation of both bones distally. Such injuries would have necessarily severed the associated Achilles tendons, hobbling the victim.

Evidence gathered during the recovery of bodies in the mass grave as well as that which was collected during autopsies including clothing and DNA samples were released to investigators for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. With no available medical records of the victims, and lacking survivors for DNA collection, identification of the remains was not even contemplated.

Investigation of Torture in Syrian Detention Centers

An enforced disappearance is an arrest, detention, or abduction, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by the concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared. The practice of forcibly disappearing persons is prohibited under customary international humanitarian law, binding all parties to the conflict in Syria. Enforced disappearances have been carried out since the beginning of the uprising in Syria. Most such disappearances in Syria are perpetrated by intelligence and security officers and by the Syrian army. Most of those detained are young, in their 20s and 30s, but children, women, and even elderly are also under detention.

As early as in 2012, Human Rights Watch identified and mapped 27 of these detention centers around the country (15). The Syrian Network for Human Rights, a local monitoring group, has made claims that Syrian government forces have detained at least 215 000 Syrians since the beginning of the uprising in March 2011 (16).

Although most of the casualties in what is now known as the Syrian Civil War are due to indiscriminate bombing, chemical weapon attack, as in Ghouta near Damascus in August 2013, extensive use of cluster munitions, high explosive barrel bombs released on civilian targets from aerial attacks, as well as use of more advanced weaponry including thermobaric weapons, reports of torture and death in Syrian detention camps began to surface.

Torture is an act that is deliberately inflicted on a person resulting in conscious pain and or suffering. Whilst pain results from a nociceptive stimulus, suffering can occur due to psychologic torture in the absence of actual physical injury and may result from fear, extreme anxiety, threats of violent acts or sexual assaults, being forced to watch the rape of another detainee, being subjected to sights and sounds of torture being inflicted on others, including of friends and family members, and being exposed to killings of torture victims. Prohibition of torture is absolute and is enshrined in Article 5 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (17).

In January 2014, a defector, code-named “Caesar,” who had worked as a forensic photographer for the Syrian Military Police, and who had personally photographed bodies of dead detainees, provided international lawyers and Syrian activists 50 000 images that he smuggled out. In 2015, Human Rights Watch requested PHR-USA to assist in the evaluation of 72 digital color photographs of 19 Syrian detainees.

Methodology

The overall method of analysis of the digital photographs consisted of peer review of each photograph on a high definition screen with a group of fellow forensic pathologists at the Tarrant County Medical Examiner's Office in Fort Worth, Texas. The objective of this peer review was to identify injury on the exposed body surface, and attempt to predict the mechanism of injury and what role it played in the death of the detainee.

Although the authenticity of a subset of photographs was confirmed by the US Federal Bureau of Investigations Digital Evidence Laboratory, Caesar's photographs were most probably taken as a part of death certification process and not produced in the manner of evidentiary photographs as would be taken by crime scene investigators. Hence, they lacked scale, context in which they were taken, close-up photos of injuries, and documentation of the backs of the bodies. Injuries that may have been present on the back could not be evaluated. This was the first weakness of this study conducted by this author.

Another weakness of this study was the absence of autopsy findings. Hence, it is not possible to rule out deaths due to plastic bag suffocation, suffocation due to overcrowding, or cardiorespiratory failure due to prolonged application of “Shabeh.” Shabeh is a well-known method of torture employed by Syrians and consists of hanging the victim from ceiling by the wrists so that his toes barely touch the ground or the victim is completely suspended (Image 10). The purpose, of course, is to inflict violent blunt force injuries in a restrained detainee. Prolonged suspension, however, may result in dire respiratory complications including death, especially in a detainee weakened by starvation, sleep deprivation, and physical beating.

Image 10.

Torture victim from a Syrian detention camp with extreme stasis of lower extremities with marked cutaneous hyperemia and edema as well as multiple contusions due to blunt force trauma. It is very likely he was a victim of Shabeh torture.

It is quite possible that many of the detainees had preexisting medical conditions. Failure to render medical care for preexisting conditions such as diabetes mellitus, bronchial asthma, seizure disorder, and others may have been the underlying cause in some of these victims.

Finally, fatal blunt force trauma to the head or torso may not always produce visible cutaneous injuries. Without autopsy, the precise cause of death in such cases cannot be established. Despite these shortcomings, this study documented 18 males and one female with estimated ages ranging from peri-adolescence to the 50s, although most of the victims were in the age group between the 20s and 40s. In five cases, the cause of death remains undetermined because of lack of sufficient photographic evidence. In the remaining 14 cases, four deaths were attributed to starvation, six deaths to violent blunt force trauma, three deaths to suffocation due to prolonged suspension (Shabeh), and one death due to penetrating gunshot wound of head.

Finally, there was clear evidence that the detainees were subjected to torture, including three victims who were subjected to Shabeh, three to “Dulab,” and two to “Falaqa.” In the setting of Dulab posture, the victim is forced to bend at the waist and stick his head, neck, legs and sometimes arms into the inside of a car tire. Sustained application of Dulab may cause suffocation or positional asphyxia due to compression of anterior neck structure with marked facial plethora and cutaneous petechiae. In Falaqa, the detainee is struck violently many times with sticks, pipes or batons on the soles of the feet. This causes serious injuries including bone fractures and nerve damage leaving the victim unable to walk subsequently and sometimes impeded for life.

Conclusion

The evolution and acceptance of what constitutes a violation of human rights and International Humanitarian Law has been slow and painful. This evolution began in 1945 at the Tribunal of Nuremberg, which judged the accused war criminals of Nazi Germany. The international community then pledged that “never again” would it allow monstrous crimes against humanity or genocide to take place. Yet, 70 years later, we continue to witness horrendous crimes against humanity, genocides, ethnic cleansing, and terrorism. Every continent has witnessed the unfolding horrors and humanitarian crisis including the many nations in the Middle East and North Africa, especially Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Palestine; over a dozen countries in Africa including Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Mozambique, and Somalia; Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Chechnya, Colombia, and Sri Lanka to name but a few. There is no doubt that some of the most serious threats to international peace and security are armed conflicts that arise, not among nations, but among warring factions within a state as in Syria, Libya, and Afghanistan. Uppsala Conflict Data Program reported 102 330 global conflicted related fatalities in 2016 including 87 098 state-based, 9034 nonstate based, and 6278 one-sided violence which includes acts of terror (18). Many of these conflicts spill over borders, endangering the security of other states and resulting in complex humanitarian emergencies. The need for forensic pathologists to help investigate such crimes against humanity in the setting of armed conflicts is crucial.

A forensic pathologist is uniquely trained to investigate many of these crimes against humanity including mass killings in the setting of a genocide, torture and death in detention, use of excessive force by combatants, and violation of medical neutrality. Being a physician, a forensic pathologist is trained to evaluate medical records, interview patients, review radiographs and computed tomography scans, and review laboratory data to document disease and trauma. Additionally, a forensic pathologist is trained and experienced to perform postmortem examinations and render opinions regarding both cause and manner of death, both in natural as well as in traumatic deaths and deaths due to poisons and chemicals. Finally, unlike other physicians, a forensic pathologist interacts with law at many levels and is well suited to be a member in a multidisciplinary team that is charged with investigating crimes against humanity in the setting of armed conflicts.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1.Constitution of the World Health Organization. In: Basic documents, 36th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. Geneva: World Health Organization: 1978. 3 p.

- 3.Mann J.M. Gruskin S. Grodin M.A. Annas G.J.. Health and human rights: a reader. New York: Routledge; c1999. Chapter 1, Human rights and public health; p. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manduca P. Chalmers I. Summerfield D. et al. An open letter for the people in Gaza. Lancet. 2014. Aug 2; 384(9941): 397–8. PMID: 25064592. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heisler M. Baker E. McKay D.. Attacks on health care in Syria–normalizing violations of medical neutrality? N Engl J Med. 2015. Dec 24; 373(26): 2489–91. PMID: 26580838. PMCID: PMC4778548. 10.1056/NEJMp1513512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ICRC Treaties, states parties and commentaries [Internet]. Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross; c2017. Geneva conventions of 1949 and additional protocols, and their commentaries; [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/vwTreaties1949.xsp?redirect=0. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kingdom of Bahrain Ministry of Health [Internet]. Manama: Kingdom of Bahrain; c2017. MOH statistics; [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: http://hajj.moh.gov.bh/EN/aboutMOH/Information/Statistics.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs [Internet]. Jerusalem: State of Israel; c2013. Suicide Bombers from Jenin; 2002 Apr 24 [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFA-Archive/2002/Pages/Suicide%20Bombers%20from%20Jenin.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNRWA [Internet]. Genevea: United Nations Rekief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East; c2017. Jenin Refugee Camp; [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/west-bank/jenin-camp. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pounder D.. Jenin 'massacre evidence growing.' BBC News [Internet]. 2002. Apr 18 [cited 2017 Jun 21]; World: Middle East. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.Uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/1937048.stm.

- 11.United Nations DAG Repository [Internet]. New York: United Nations; c2017. Security Council resolution 1405 (2002) on initiative for fact-finding team for Jenin refugee camp; 2002 Apr 19 [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: http://repository.un.org/handle/11176/28064. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamir S, Aluf B, Ha' Agencies. Ben-Eliezer, Peres to Annan: Israel unhappy with Jenin delegation. Haaretz [Internet]. 2002. Apr 22 [cited 2017 Jun 21]; News. Available from: http://www.haaretz.com/news/ben-eliezer-peres-to-annan-israel-unhappy-with-jenin-delegation-1.47169.

- 13.Lemkin R.. Axis rule in occupied Europe: laws of occupation – analysis of government – proposals for redress. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; 1944. Chapter IX, Genocide; p. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Castillo-Calcáneo J.D. Bravo-Angel U. Mendez-Olan R. et al. Traumatic brain injury with a machete penetrating the dura and brain: Case report from southeast Mexico. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016; 23: 169–72. PMID: 27156252. PMCID: PMC5022070. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Human Rights Watch [Internet]. New York: Human Rights Watch; c2017. If the dead could speak: mass deaths and torture in Syria's detention facilities; 2015 Dec 16 [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/12/16/if-dead-could-speak/mass-deaths-and-torture-syrias-detention-facilities. [Google Scholar]

- 16.VOA [Internet]. Washington: Voice of America; c2017. Rights group: 215,000 detained in Syria since uprising; 2014 Dec 17 [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.voanews.com/a/rights-group-detentions-syria/2563705.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Universal declaration of human rights [Internet]. Geneva: United Nations; 1948. 8 p. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uppsala Universitet Department of Peace and Conflict Research [Internet]. Uppsala (Sweden): Uppsala Universitet; c2014. Uppsala conflict data program; [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: http://ucdp.uu.se/. [Google Scholar]