Abstract

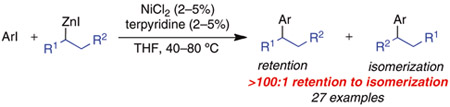

A general Ni-catalyzed process for the cross-coupling of secondary alkylzinc halides and aryl/heteroaryl iodides has been developed. This is the first process to overcome the isomerization and β-hydride elimination problems that are associated with the use of secondary nucleophiles, and that have limited the analogous Pd-catalyzed systems. The impact of salt additives was also investigated. It was found that the presence of LiBF4 dramatically improves both isomeric retention and yield for challenging substrates.

Transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of C(sp2) organometallic nucleophiles with C(sp2) electrophiles have been thoroughly studied and developed over the past few decades.1a More recently, the use of C(sp3) nucleophiles and C(sp3) electrophiles has been demonstrated in Pd-, Cu-, Ni-, Fe-, Co-, and Ag-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.1 However, a general procedure that enables the cross-coupling of secondary nucleophiles and aryl halides has not yet been demonstrated.2,3 The recent Pd-catalyzed methods developed by Molander/Dreher3c and Buchwald3d constitute the only comprehensive efforts toward establishing a general protocol for such cross-coupling reactions. Unfortunately the Pd-catalyzed systems often suffer from isomerization of secondary alkyl nucleophiles on account of facile β-hydride elimination and slow reductive elimination.1a Isomerization is less problematic when using electronically or sterically activated arenes since these substrates experience accelerated reductive elimination relative to β-hydride elimination.4 Such substitution effects have been shown for both Pd- and Ni-catalyzed systems.3j However, the utility of the process is reduced if the scope of electrophiles is limited to such activated substrates. The use of symmetric, cyclic (e.g., cyclohexyl or cyclopentyl) nucleophiles precludes isomerization, but an ideal process should accommodate a large range of nucleophiles. Based upon the success of Ni catalysis in cross-coupling reactions involving an alkyl component,1b we postulated that a new Ni-catalyzed process could surmount the problems inherent to the analogous Pd-catalyzed systems. Herein, we report a general Ni-catalyzed process that enables the cross-coupling of unactivated, acyclic secondary alkylzinc halides with aryl and heteroaryl iodides without competitive isomerization of the nucleophile. This process is the first to overcome the problem of β-hydride elimination observed in Pd-catalyzed systems, thus enabling the direct and rapid preparation of arenes bearing secondary alkyl substituents.

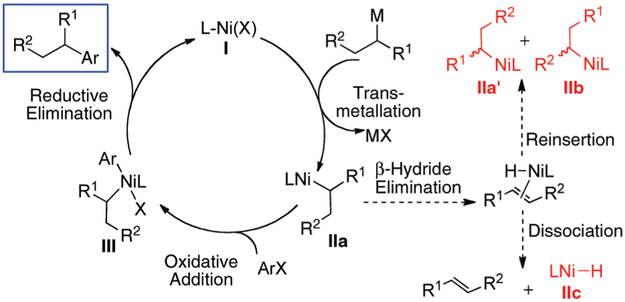

Figure 1 shows a plausible catalytic cycle for the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of a secondary nucleophile and an aryl halide.5 After transmetallation, the secondary alkyl ligand of complex IIa may undergo isomerization (IIb) and racemization (IIa′) (if optically active) through a β-hydride elimination/reinsertion sequence. Dissociation of the olefin after β-hydride elimination would result in the formation of a nickel hydride complex (IIc), which may lead to catalyst deactivation or aryl halide reduction. According to this model, the elementary steps of the catalytic cycle must out-compete β-hydride elimination to create an efficient catalytic process.6

Figure 1.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of secondary alkyl nucleophiles and aryl halides.

From an initial screen of different ligand classes (see the Supporting Information), bidentate and tridentate nitrogen-based ligands appeared most promising in effecting the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of iodobenzene and s-BuZnI. Indeed, the Cardenas group has shown the ability of bidentate nitrogen ligands to support the oxidative addition of aryl halides to nickel,3j and the Fu group has repeatedly shown the ability of tridentate nitrogen-based ligands to support Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions involving alkyl nucleophiles and electrophiles.7 The ability of the tridentate terpyridine scaffold to support the oxidative addition of aryl halides to nickel, however, has not been explored.

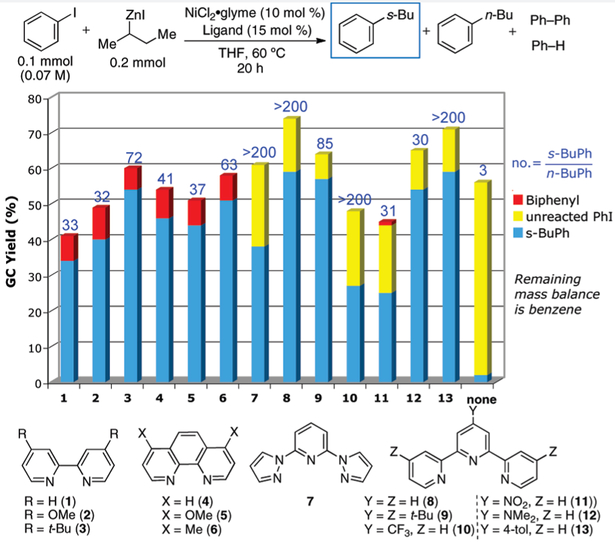

Using 10 mol % NiCl2 · glyme and 15 mol % ligand, we investigated the use of bidentate and tridentate nitrogen-based ligands more extensively (Figure 2). The ratios of s-BuPh to n-BuPh products were generally high with unhindered bipyridine, phenanthroline, and terpyridine ligands, but were greatest with terpyridine derivatives (i.e. > 200:1). Additionally, the formation of homocoupling product8 was completely suppressed when terpyridine ligands were employed. Electronic perturbations, introduced by modifying terpyridine (8), did not improve the efficiency of the catalytic process. Additionaly, the inclusion of ortho-substituents on the ligands destroyed the activity of the catalyst (see the Supporting Information). Thus, 8 was employed in ensuing optimization studies. Upon increasing the reaction concentration from 0.07 to 0.60 M, the yield improved to 93% (Table 1) as the competitive reduction of iodobenzene was suppressed. At such a concentration, we were additionally able to lower the nickel and ligand loadings to 2 mol %, reduce the alkylzinc iodide to 1.5 equiv, and replace NiCl2 · glyme with NiCl2,9 while obtaining > 500:1 selectivity for the desired branched product over the isomerization product. The addition of cosolvents such as DME, DMF, DMA, and NMP resulted in significantly decreased yields and increased formation of isomerized, linear product.

Figure 2.

Ligand screen for the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of iodobenzene and s-BuZnI.

Table 1.

Optimization of Conditions for the Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction of Iodobenzene and s-BuZnla

| entry | L | variation from conditions of Figure 2 | yield (%) | s-Bu/n-Bu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 0.15 M in THF | 93 | 200/1 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.15 M in THF | 53 | 70/1 |

| 3 | 6 | 0.15 M in THF | 80 | 60/1 |

| 4 | 8 | 0.45 M in THF | 91 | 200/1 |

| 5 | 8 | 0.45 M in THF, 2% NiCl2·glyme, 2% L | 96 | 300/1 |

| 6 | 8 | 0.45 M in THF, 2% NiCl2, 2% L | 98 | >500/1 |

| 7 | 8 | 0.60 M in THF, 2% NiCl2, 2% L, 1.5 equiv of RZnI | 93 | >500/1 |

Yields and selectivities determined by GC with dodecane as an internal standard.

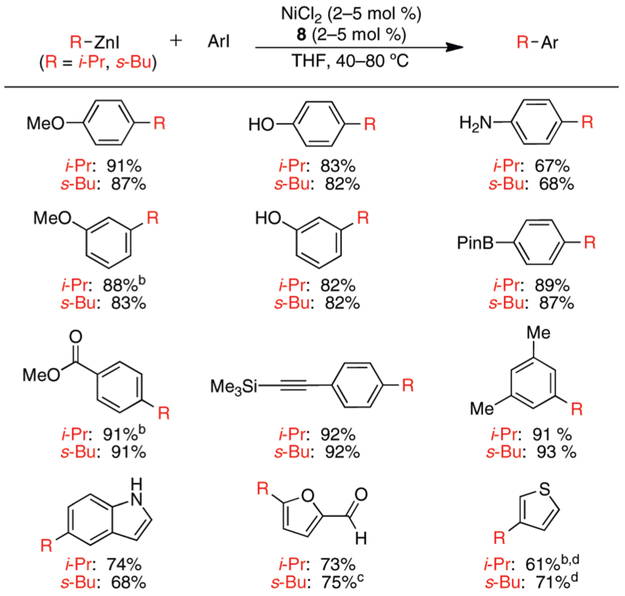

Using the conditions described above, we explored the generality of this process with respect to the aryl iodide employed. Additionally, we subjected each aryl iodide to reactions with i-PrZnI and s-BuZnI to gather insight into the general sensitivity of the method to α-branching on the nucleophile. We observed no dependence on the electronic properties of the aryl iodide or on the use of an α-branched nucleophile (Scheme 1). The ratio of branched (retention) product to linear (isomerization) product was greater than 100:1 in each of these reactions.10,11 In a few instances, exogenous LiBF4 was employed to eliminate the formation of small amounts of linear byproduct (discussed below). Thus, β-hydride elimination can be successfully avoided by using these general conditions. To demonstrate the scope and utility of this method, we concentrated on functionalized substrates that have been traditionally difficult to employ in cross-coupling reactions. In most cases, excellent yields of the desired product were isolated. Aldehydes, esters, arylboronic esters, phenols, anilines, alkynes, and heterocycles were all successfully tolerated in these reactions. Thus, this process is remarkably general with respect to the functional groups of the aryl iodide component. The use of ortho-substituted aryl iodides generally led to low conversion and significant aryl iodide reduction. However, the analogous Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling process is particularly facile when an ortho-substituent is present on the aryl halide to accelerate reductive elimination.3d Thus, our Ni-catalyzed system appears to be highly complementary to the Pd-catalyzed process.

Scheme 1.

Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of i-PrZnI and s-BuZnI with Aryl and Heteroaryl Iodides

a ArI (1 mmol), RZnI (1.5–2.5 mmol); average isolated yield of 2 runs; all products are formed with > 100:1 branched to linear ratio. b With LiBF4 (1 equiv) as additive. c 70:1 s-Bu to n-Bu; see ref 11. dVolatile products: GC yields are 80% (i-Pr) and 82% (s-Bu).

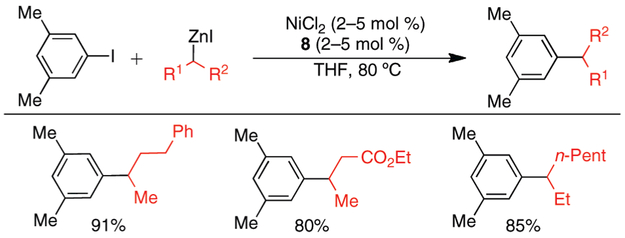

To verify that secondary alkylzinc nucleophiles can be employed in this Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction in a general fashion with isomeric retention, we performed cross-coupling reactions with acyclic alkylzinc nucleophiles other than i-PrZnI and s-BuZnI (Scheme 2). Notably, we successfully employed a secondary alkylzinc reagent bearing an ester, as well as a secondary alkylzinc reagent with α-branching on both alkyl substituents. These reactions occurred in good to excellent yields without detectable isomerization of the nucleophile.

Scheme 2.

Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of 1-Iodo-3,5-Dimethylbenzene with Different Secondary Alkylzinc Iodidesa

a ArI (1 mmol), RZnI (1.3–1.5 mmol); average isolated yield of 2 runs.

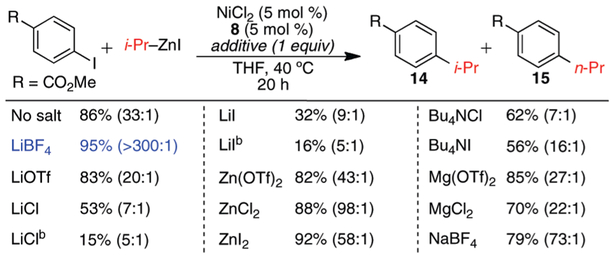

During our initial investigation into the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl iodides and secondary alkylzinc nucleophiles, we observed that both yield and selectivity were greatly influenced by the presence oflithium chloride in the reaction mixture. When alkylzinc reagents were prepared with LiCl according to the procedure of Knochel,12 yields of cross-coupling products were low and ca. 5–10% linear product was observed. This observation, as well as the reported ability of exogenous salts to facilitate Negishi reactions13 and certain Ni-catalyzed cross-couplings,14 inspired us to investigate the effect of salt additives on this process. While the majority of substrates included in Scheme 1 underwent cross-coupling with > 100:1 branched to linear product ratio, four of the substrates did show more significant formation of linear alkyl products when the conditions derived in Table 1 were employed. The greatest extent of isomerization was observed in the cross-coupling of methyl 4-iodo-benzoate and s-BuZnI, where the s-Bu (14) and n-Bu (15) products were formed in a ratio of 33:1, respectively. Thus, we employed this substrate in our model study on the effect of different salt additives on yield and selectivity. The results of this study are shown in Scheme 3. In all instances, complete conversion of PhI was observed. The presence of LiCl and LiI showed a dramatic inhibitory effect on the cross-coupling reaction, which became more pronounced as the salt concentration was increased. This coincided with a shift in the reaction selectivity toward the linear product (15) and the homocoupling product. While increasing the concentration of halide salts had an adverse effect in most cases, the use of exogenous zinc halides had a marginally beneficial effect on both yield and selectivity. By far, the greatest positive effect was observed when LiBF4 was employed as an additive. With LiBF4, the reaction yield increased to 95% and the formation of linear product was completely suppressed. In addition to suppressing the isomerization of the secondary nucleophile, the addition of LiBF4 also helped to diminish arene formation from aryl iodide reduction. Thus, if necessary, LiBF4 can be employed as an additive in instances where isomerization or reduction byproduct is undesirably high. Since the addition of lithium halide salts has been shown to facilitate Pd-catalyzed Negishi cross-coupling reactions,13 it is surprising that the addition of lithium halide salts is so deleterious to the outcome of the Ni-catalyzed process. These salt effects are particularly important to consider when preparing alkylzinc reagents via methods involving the concurrent formation of salt byproduct.

Scheme 3.

Effect of Exogenous Salts on Yield and Isomerization (14:15)a

a Yields and selectivities determined by GC with dodecane as an internal standard. b 3 equiv added.

Because we are interested in developing methods of high operational simplicity as well as generality, we performed each of these reactions on the benchtop, using readily available disposable vials with screw-top septa. The reaction vials were evacuated and backfilled with argon prior to the addition of the alkylzinc reagent, sealed with electrical tape, and allowed to stir in the absence of additional argon pressure. When the optimized conditions described in Table 1 were applied to the cross-coupling reaction of iodobenzene and s-BuZnI without any precaution to exclude air or moisture, the observed yield only fell to 86%. Thus, while we recommend that these reactions be performed under an inert atmosphere of nitrogen or argon if possible, the described system appears not to be especially sensitive to air and moisture.

In summary, we have developed the first general procedure for the cross-coupling of secondary nucleophiles and aryl/heteroaryl iodides. This process solves the problem of isomerization inherent to analogous Pd-catalyzed reactions. Accordingly, the use of nickel catalysis should be preferred in most cases where potential isomerization of the nucleophile is a concern. We are currently pursuing kinetic studies on this transformation, through which we hope to elucidate the mechanism involved and the role of salt additives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

We thank The City College of New York (CCNY) and PSC–CUNY for financial support. We gratefully acknowledge the National Science Foundation for an instrumentation grant (CHE-0840498). Acknowledgment is additionally made to the donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (50307-DNI1) for partial support of this research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and spectral data for all products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions; de Meijere A, Diederich F, Eds., Wiley-VCH: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]; (b) (c) Rudolph A; Lautens M Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 2656 and references cited therein. Vechorkin O; Hu X Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 2937 and references cited therein.. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Original pioneering study:; Tamao K; Kiso Y; Sumitani K; Kumada M J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 9268. [Google Scholar]

- (3).For recent examples of secondary nucleophiles in Pd catalysis, see:; (a) Campos KR; Klapars A; Walsman JH; Dormer PG; Chen C J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Luo X; Zhang H; Duan H; Liu Q; Zhu L; Zhang T; Lei A Org. Lett 2007, 9, 4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dreher SD; Dormer PG; Sandrock DL; Molander GA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Han C; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Thaler T; Haag B; Gavryushin A; Schober K; Hartman E; Gschwing RM; Zipse H; Mayer P; Knochel P Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nakao Y; Takeda M; Matsumoto T; Hiyama T Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 45, 4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Sandrock DL; Jean-Gerard L; Chen C-Y; Dreher SD; Molander GA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 17108 For recent examples of secondary nucleophiles in Ni catalysis, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Melzig L; Gavryushin A; Knochel Org. Lett 2007, 9, 5529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Smith SW; Fu GC Angew.Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 9334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Phapale VB; Guisan-Ceinos M; Bunuel E; Cardenas DJ Chem.—Eur. J 2009, 15, 12681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).The presence of an ortho-substituent or an electron-withdrawing group on the electrophilic component of Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions has been shown to accelerate reductive elimination. See:; (a) Crabtree RH The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Torraca KE; Huang X; Parrish CA; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 10770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Culkin DA; Hartwig JF Organometallics 2004, 23, 3398. [Google Scholar]

- (5).While a Ni(0)–Ni(II) catalytic cycle cannot be conclusively ruled out, structural and computational studies support a Ni(I)–Ni(III) catalytic cycle for such Ni-catalyzed reactions when bi- and tridentate nitrogen are employed as the supporting ligand. See ref 3h.; (a) Anderson TJ; Jones GD; Vicic DA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 8100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones GD; Martin JL; McFarland C; Allen OR; Hall RE; Haley AD; Brandon RJ; Konovalova T; Desrochers PJ; Pulay P; Vicic DA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 13175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Phapale VB; Cardenas DJ Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Zhou J; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 14726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arp FO; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 10482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fischer C; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Son S; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Smith SW; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lundin PM; Esquivias J; Fu GC Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tsou TT; Kochi JK J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 7547. [Google Scholar]

- (9).NiCl2 ($0.43/g from Strem) is considerably less expensive than NiCl2·glyme ($13.12/g from Strem) and Pd(OAc)2 ($27.12/g from Strem).

- (10).The > 100:1 ratio of retention to isomerization is conservative. GC analyses show that the majority of these reactions favor retention by a ratio of > 500:1.

- (11).The use of exogenous LiBF4 improved isomeric retention in the cross-coupling of iodofuraldehyde and s-BuZnI, but greatly reduced the yield.

- (12).(a) Krasovskiy A; Malakhov V; Gavryushin A; Knochel P Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 6040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Knochel P; Singer RD Chem. Rev 1993, 93, 2117 For salt-free conditions, see: Huo S Org. Lett 2003, 5, 423. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Achonduh GT; Hadei N; Valente C; Avola S; O’Brien CJ; Organ MG Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Spielvogel DJ; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderson TJ; Vicic DA Organometallics 2004, 23, 623. [Google Scholar]; (c) Colon I; Kelsey DR J. Org. Chem 1986, 51, 2627. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.