Abstract

Background:

Alcohol myopia theory postulates that the level of alcohol use in conjunction with personal cues such as alcohol attitudes and personality traits help to understand the types of consequences manifested.

Objectives:

This study examined and identified the personality traits that served as predictors and moderators of the risk connections from drinking attitudes to alcohol use to myopia outcomes.

Methods:

College students (N = 433) completed self-report measures. In a path analysis using structural equation modeling, personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism), drinking attitudes, and personality x drinking attitudes interactions simultaneously served as predictors on the outcomes of alcohol use and myopic relief, self-inflation, and excess.

Results:

Alcohol attitudes and use consistently emerged as unique predictors of all three myopia outcomes. Extraversion and neuroticism were identified as statistical moderators, but results varied depending on the myopia outcome interpreted. Specifically, extraversion moderated the pathways from attitudes to usage and from attitudes to myopic relief. Neuroticism, however, moderated the relations from attitudes to myopic self-inflation and from attitudes to myopic excess.

Conclusions/Importance:

Extraverted and neurotic dispositions could exacerbate or attenuate the risk connections from alcohol attitudes to outcomes. Findings offer implications for alcohol prevention efforts designed to simultaneously target drinking attitudes, personality traits, and alcohol myopia.

Keywords: alcohol, alcohol myopia, personality, attitude to behavior consistency, relief, self-inflation, excess

Introduction

Alcohol use is especially prevalent in young adults, with four out of every five college students consuming this psychoactive substance (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015). Alcohol intake could produce an array of psychological, social, and physical repercussions (Navarro, Doran, & Shakeshaft, 2011). Consumption might yield coveted consequences such as feelings of relaxation (Friedman, McCarthy, Bartholow, & Hicks, 2007) and bolstered perceptions of self-esteem (Sevincer & Oettingen, 2013; Wolfe & Maisto, 2000). Conversely, alcohol use can also furnish undesirable consequences including unprotected sex (Griffin, Umstattd, & Usdan, 2010), aggression (Giancola, 2004), destruction of property (Navarro et al., 2011), sexual assault (Flowe, Stewart, Sleath, & Palmer, 2011), and drunk driving (Fromme, Wetherill, & Neal, 2010). The diversity in the possible types of outcomes experienced after alcohol intake could be understood through the mechanisms posited in alcohol myopia theory (Steele & Josephs, 1990).

Theoretical frameworks focusing on attitude to behavior consistency maintain that attitudes are important predecessors of behavioral outcomes (Ajzen, 1991; Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992). Accordingly, positive attitudes regarding alcohol correspond to greater levels of consumption and consequences (Lac, Crano, Berger, & Alvaro, 2013; Lac & Donaldson, 2018; Napper, Hummer, Lac, & Labrie, 2014). Furthermore, personality traits could serve as dispositional factors that make people vulnerable to problematic drinking outcomes (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Rooke, & Schutte, 2007). The current study sought to examine alcohol attitudes and personality traits as predictors and moderators on the outcomes of alcohol usage and myopia consequences.

Personality Traits and Alcohol Outcomes

A wide body of research supports the practical applications of the five-factor model of personality (Costa & McCrae, 1995; McCrae & Costa, 1987, 1997). This theoretical paradigm to capture and understand personality structure provides a way to measure how people vary in their interpersonal, attitudinal, experiential, and motivational styles (McCrae & John, 1992). The five-factor model embodies the following personality dimensions (Costa & McCrae, 1995; McCrae & Costa, 1987, 1997): extraversion (gregarious, sociable, warm, and assertive); agreeableness (trustworthy, altruistic, kind, and prosocial); conscientiousness (thoughtful, dependable, responsible, and competent); openness (intellectually curious, receptive to novel experiences, imaginative, and adventurous); and neuroticism (emotionally unstable, anxious, uncertain, and impulsive).

Previous research applying the five-factor personality model determined that this paradigm helps to understand person-to-person variations in drinking outcomes (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Malouff et al., 2007). Higher extraversion and higher neuroticism have both been shown to be associated with risky alcohol consumption (Cook, Young, Taylor, & Bedford, 1998; Hakulinen et al., 2015; Hicks, Durbin, Blonigen, Iacono, & McGue, 2012; Hussong, 2003). Furthermore, Cooper, Agocha, and Sheldon (2000) contend that extraversion and neuroticism promote alcohol involvement and risky consequences via motivational pathways. They discovered that extraverts drink to enhance social situations and cultivate positive affective states, whereas neurotics drink to cope with anxieties by avoiding negative affective states. Research also shows that the impulsivity component embedded in neuroticism is responsible for encountering hazards induced by alcohol (Ruiz, Pincus, & Dickinson, 2003). A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies documented that low agreeableness, low conscientiousness, and high neuroticism were predisposing factors to consuming greater amounts of alcohol (Malouff et al., 2007). Other cross-sectional meta-analyses have disclosed that high neuroticism and low conscientiousness were linked with substance use disorders (Kotov et al., 2010) and that low conscientiousness is linked with excessive alcohol consumption (Bogg & Roberts, 2004). A meta-analysis (Hakulinen et al., 2015) synthesizing prospective studies concluded that high extraversion and low conscientiousness elevated the vulnerability to consuming alcohol longitudinally.

Alcohol Myopia

Alcohol is a substance capable of interfering with normal cognitive processes and functioning (Geibprasert, Gallucci, & Krings, 2010). Alcohol myopia theory (Josephs & Steele, 1990; Steele & Josephs, 1990) was postulated to recognize and understand the psychoactive demands of alcohol and proposes that this substance narrows mental resources by modifying the scope and focus of attention via myopic effects (Giancola, Josephs, Parrott, & Duke, 2010). The type of myopia experienced is an individual differences variable responsible for the differential reactions and outcomes (e.g., relaxation, self-esteem boost, erratic behaviors) incurred by different people after drinking (Monti, Rohsenow, & Hutchison, 2000). Steele and Josephs (1990) reviewed the literature and identified three underlying types of alcohol myopia: relief, self-inflation, and excess.

Alcohol furnishes myopic relief by temporarily alleviating negative feelings, anxiety, and stress (Lac & Berger, 2013; Steele & Josephs, 1988). Relief and relaxation after consumption are attributed to the narrowing of attention previously allocated to the processing of undesirable thoughts and mood states (Josephs & Steele, 1990). Stress relief and tension reduction are widely known effects of alcohol ingestion and embody common utilitarian reasons for why people reach for the bottle (Friedman et al., 2007). Alcohol’s effects on neural processes (Polivy, Schueneman, & Carlson, 1976; Wilson & Abrams, 1977) in conjunction with mental activation of beliefs about the relaxation properties of alcohol (Friedman et al., 2007; Schmidt, Eulenbruch, Langer, & Banger, 2013) are responsible for relief experiences.

Myopic self-inflation occurs when perceptions of enhanced self-image leading to ego-inflated tendencies are manifested after alcohol ingestion (Steele & Josephs, 1988). These drinkers achieve a self-confidence boost by temporarily failing to fully process information about personal limitations and flaws (Sevincer & Oettingen, 2013; Wolfe & Maisto, 2000). Alcohol furnishes people with the liquid courage to navigate social environments by approaching strangers and potential romantic partners (Monahan & Lannutti, 2000; Peele & Brodsky, 2000; Smith, Kendrick, & Maben, 1992). People with poor social self-esteem become more flirtatious when drinking compared to when they are sober (Monahan & Lannutti, 2000).

Myopic excess occurs when impulse control becomes disinhibited and consequently manifested in reactive and erratic behaviors (Bushman & Cooper, 1990; Steele & Josephs, 1990). After intoxication, these individuals are provoked easily by discomfort and annoyances, act in ways that are socially unacceptable, and lack insights about the long-term consequences of their actions (Perkins, 2002). Those experiencing myopic excess may be more inclined to drive a vehicle while intoxicated (MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong, 1995), injure oneself (Perkins, 1992), destroy property (Engs & Hanson, 1994), partake in unprotected sexual activity (MacDonald, Fong, Zanna, & Martineau, 2000), commit sexual violence (Abbey, McAuslan, & Ross, 1998), and exhibit other antisocial and aggressive tendencies (Giancola, 2004).

Current Study

The present investigation examined alcohol attitudes and personality traits as predictors and moderators of alcohol outcomes (usage, relief, self-inflation, and excess). Alcohol myopia theory postulates that person-to-person variations in myopic experiences are attributed to the amount of alcohol consumed in conjunction with salient personal and dispositional cues (Lac & Berger, 2013; Lac & Brack, 2018; Steele & Josephs, 1990). Accordingly, personality traits might serve as internal facilitating or inhibiting cues that modify the vulnerability to each type of alcohol myopia (Davis, Hendershot, George, Norris, & Heiman, 2007). Specifically, personality attributes could act as contextual mental guides (Conner & Abraham, 2001) in enhancing or reducing the predictive association from alcohol attitudes to myopic effects. Thus, personality traits could additionally account for variations in susceptibility to each type of myopia over and beyond drinking levels.

The current research extends upon the previous literature in several ways. First, prior investigations have predominantly focused on the main predictive effects of personality traits on alcohol behavioral outcomes (Lac & Donaldson, 2016; Malouff et al., 2007), but has largely neglected to scrutinize the moderating role of personality. Given that prevention efforts are informed by identifying the potential moderators of risk connections (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009), findings are anticipated to offer insights regarding the dispositional traits that modify attitude to behavior consistency in the context of drinking. Second, a comprehensive review of the literature indicates that this is the first investigation to simultaneously test statistical associations of all Big 5 personality traits with all 3 alcohol myopia outcomes. A previous study, for example, only tested relations involving temperament (emotionality, activity level, social interest, and impulsiveness) and a general measure of myopia (Elias, Bell, Eade, & Underwood, 1996). The present research is anticipated to yield insights regarding the constellation of personality traits that differentially predispose people to experience each myopic relief, self-inflation, and excess.

A path model involving mediation and moderation analyses was performed. Personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism), alcohol attitudes, and alcohol attitudes x personality interactions were hypothesized to predict alcohol use. All of these variables were permitted to predict the outcomes of myopic relief, self-inflation, and excess. Essentially, the pathways from alcohol attitudes and personality traits to alcohol myopia were proposed to be mediated by alcohol use. Additionally, age, gender, race, and housing status served as covariates to statistically rule out these demographic variables.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 433 undergraduate students enrolled in a medium-sized university. Participants reported a mean age of 18.95 years (SD = 1.13), with a gender distribution of 57% females and 43% males. The racial composition included 62% White, 17% Latino, 5% Black, and 16% Asian. Most resided on-campus (81%), with the remainder living off-campus with (7%) or without (12%) parents.

Procedures

Students enrolled in introductory psychology courses were invited to take part in the study for extra credit or subject pool credit. The instructor of each course decided upon the point amount granted for participating in the study. Information about the study was announced in classes and posted on the online subject pool. Participants received an email containing a link to the web-based survey after signing up. Two follow-up emails were sent to remind participants to complete the questionnaire. The questions in the study were completed in approximately 10 to 15 minutes. Data were collected during the Spring and Fall semesters in 2014. The research protocols were approved by an IRB.

Measures

Demographics.

Respondents completed questions about age (“What is your age?”), gender (“What is your gender?”), race (“Which best describes your race/ethnicity?”), and housing status (“Currently, where do you live?”).

Personality.

The Big Five personality taxonomy (Costa & McCrae, 1995) was captured using the 44-item version (John, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999). Participants read the stem (“I am someone who:”) and then rated each item. The subscales included extraversion (α = .88; 8 items; e.g., “Is outgoing, sociable”), agreeableness (α = .76; 9 items; e.g., “Is generally trusting”), conscientiousness (α = .90; 9 items; e.g., “Makes plans and follows through with them”), openness (α = .80; 10 items; e.g., “Is curious about many different things”), and neuroticism (α = .80; 8 items; e.g., “Can be moody”). Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses to negatively phrased items were reversed scored. Higher mean composites scores represented greater degree of the personality traits.

Alcohol Attitudes.

Drinking attitudes were assessed with a 7-item scale shown to exhibit desirable internal consistency and construct validities (Lac & Donaldson, 2016). Participants rated the following items: (a) “Drinking alcohol is good”; (b) “Drinking alcohol is positive”; (c) “Drinking alcohol is pleasurable”; (d) “Drinking alcohol is enjoyable”; (e) “Drinking alcohol is fun”; (f) “Drinking alcohol is relaxing”; and (g) “Drinking alcohol is pleasurable.” Response options were anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A mean composite was computed (α = .95), with higher scores representing more positive alcohol attitudes.

Alcohol Usage.

Alcohol intake was captured with three items: (a) “How often are you drinking alcohol”; (b) “How often are you drinking a lot?”; and (c) “How often are you getting drunk?” Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (2-3 times a month) to 7 (daily). A mean composite (α = .95) was computed.

Alcohol Myopia.

The 14-item Alcohol Myopia Scale (Lac & Berger, 2013) captured the three types of myopic effects postulated in alcohol myopia theory. That scale validation study established a three-factor structure (relief, self-inflation, and excess) premised on exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Relief and self-inflation were correlated at .59, relief and excess at .52, and self-inflation and excess at .54 in that research. The study also indicated that each factor was internally consistent and exhibited desirable discriminant, convergent, criterion, and incremental validities.

Instructions for the scale indicated, “People have different experiences when they are under the influence of alcohol. Of all the occasions you drank alcohol in the past 30 days, indicate how often you experienced each of the following effects.” Participants read the stem (“On the occasions I drank alcohol:”) followed by items assessing the subscales of relief (α = .96; 5-items; e.g., “I experienced relief” and “I worried less”), self-inflation (α = .95; 5-items; e.g., “I experienced higher self-esteem” and “I viewed myself more positively”), and excess (α = .93; 4-items; e.g., “I acted in a more extreme way” and “I was more exaggerated in my behaviors”). Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (half of the time) to 7 (always). Mean composites were created, such that higher scores represented greater levels of each myopia type.

Statistical Analyses

A path analysis using structural equation modeling was performed. The model was specified using Mplus software (Muthen & Muthen, 2017) and estimated with maximum likelihood. In this predictive model, personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism), and interactions involving alcohol attitudes and each personality trait were set to explain alcohol use. Furthermore, all the aforementioned variables were specified to explain myopic relief, self-inflation, and excess. This mediational model from alcohol attitudes and personality traits to alcohol use to myopic consequences was additionally evaluated with tests of indirect effects (Muthen & Muthen, 2017).

The highest absolute skewness level of 0.87 indicated that the variables exhibited reasonable boundaries of normality (Howell, 2002; Tabachnick, 2012). The highest inflation variance factor of 2.06 disclosed no multicollinearity problems (Tabachnick, 2012). The overall fit of the model was evaluated using several fit indices. A nonsignificant model chi-square test is desired but tends to be sensitive in erroneously rejecting the model if the sample is not small (Bollen, 1989). The CFI and TLI values of .90 or higher represent adequate fit and.95 or higher represent excellent fit (Byrne, 2012; Ullman & Bentler, 2003). The RMSEA and SRMR are sensitive in detecting model misspecifications, with values above .10 signifying poor fit for the former (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996) and above .08 indicating undesirable fit for the latter (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

The estimation and graphing of interaction terms using quantitative predictors in path analysis adhered to recommended procedures (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991; Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003; Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Sardeshmukh & Vandenberg, 2017). Accordingly, all predictors were standardized (Z-scored), and interaction terms were computed using these standardized variables. Interaction terms attaining significance were graphed at −1 SD (negative alcohol attitudes) and +1 SD (positive alcohol attitudes) for the predictor, and −1 SD (low personality trait) and +1 SD (high personality trait) for the moderator. Next, tests of simple slopes decomposed the interaction terms (Dawson, 2014), to ascertain whether the prediction slope from attitudes to an outcome, for each the low and high levels of a personality trait, significantly differed from a slope of no relation (β = 0.00).

Results

Descriptive Information

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in Table 1. A repeated-measures analysis of variance found a significant omnibus main effect across the mean scores of the three myopia subscales, F(2, 876) = 118.06, p < .001. Follow-up paired t tests indicated that participants were significantly most likely to experience relief, followed by excess, and lastly self-inflation, all ps < .001.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Extraversion | 3.31 | .75 | ||||||||||

| 2 Agreeableness | 3.77 | .54 | .21 | |||||||||

| 3 Conscientiousness | 3.59 | .58 | .19 | .32 | ||||||||

| 4 Openness | 3.58 | .58 | .18 | .14 | -.01 | |||||||

| 5 Neuroticism | 2.87 | .68 | -.34 | -.33 | -.16 | .00 | ||||||

| 6 Alcohol Attitudes | 4.19 | 1.24 | .12 | -.01 | -.08 | .12 | -.09 | |||||

| 7 Alcohol Use | 3.23 | 1.67 | .20 | .07 | -.13 | .02 | -.16 | .66 | ||||

| 8 Myopic Relief | 3.47 | 1.83 | .04 | .05 | -.10 | .15 | .01 | .56 | .51 | |||

| 9 Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.49 | 1.53 | -.04 | .01 | -.09 | .04 | .09 | .47 | .48 | .65 | ||

| 10 Myopic Excess | 2.82 | 1.56 | .08 | -.01 | -.14 | .08 | .00 | .50 | .57 | .67 | .69 |

Correlation coefficients of /.12/ or higher are signnificant, p < .05.

Predicting Alcohol Use

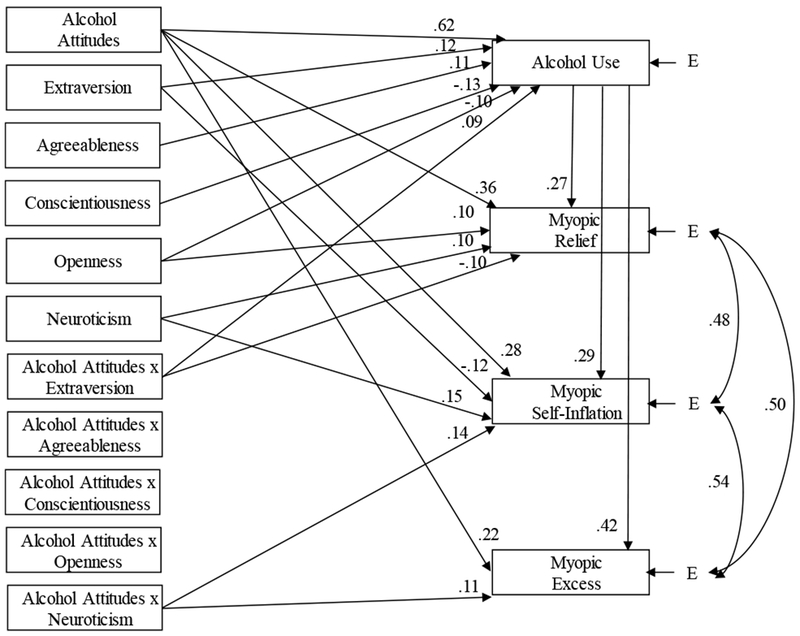

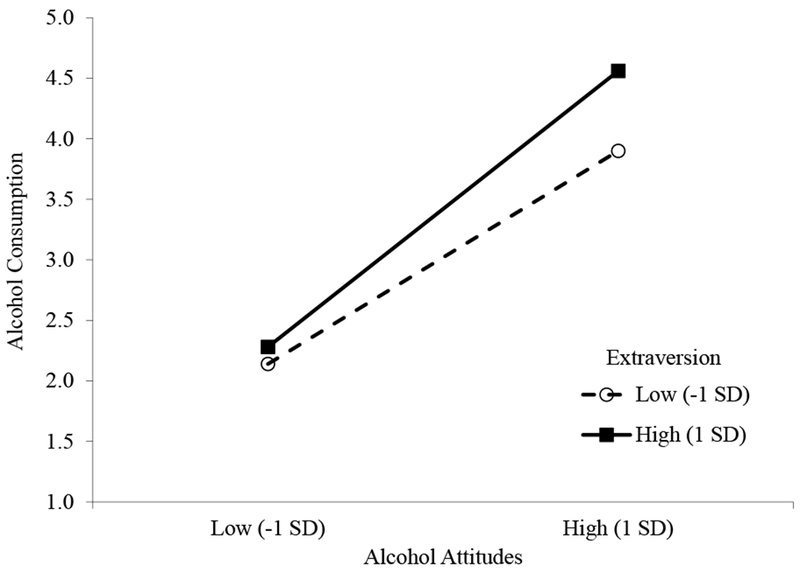

The entire path model produced adequate fit indices χ2 = 167.74, df = 65, p < .05, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI: .05 to .07], SRMR = .040. The results are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. Specifically, positive alcohol attitudes, higher extraversion, higher agreeableness, lower conscientiousness, lower openness, and the attitudes x extraversion interaction uniquely explained higher alcohol use. The significant interaction effect is graphed in Figure 2: The prediction magnitude from alcohol attitudes to usage was stronger in extraverted compared to introverted participants. Specifically, extraverts who possessed favorable alcohol attitudes possessed greater risk for alcohol intake than introverts. Tests of simple slopes supported that the relation magnitude from alcohol attitudes to consumption was significant in participants personified by high (β = .69, p < .001) and low (β = .53, p < .001) extraversion.

Figure 1.

Path analysis of alcohol attitudes and personality traits to alcohol use to myopia outcomes. For diagrammatic clarity, only significant standardized paths are displayed, p < .05. All nonsignificant paths remain estimated in this model to continue to control for all main effects and interactions. Correlations across the five personality traits were estimated as part of this model and presented in Table 2. To rule out the demographic variables (not displayed), age, gender, race (comparison groups: Latino, Black, Asian; reference group: White), and housing status (comparison groups = living off campus without parents and living off campus with parents; reference group: living on campus) were all permitted to serve as covariates on alcohol use and all three myopia composites. Male gender (β = .08, p < .05) was more likely, Latino (β = −.10, p < .05), Black (β = −.09, p < .05), and Asian (β = −.10, p < .05) were less likely than White race, and living off campus with parents (β = −.08, p < .05) compared to on campus were less likely to predict higher alcohol use. Younger age predicted higher self-inflation (β = −.20, p < .05), p < .05. The other paths from demographic covariates were not significant.

Table 2.

Correlations Involving the Personality Traits in the Path Model of Figure 1

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Extraversion | |||||

| 2 Agreeableness | .21* | ||||

| 3 Conscientiousness | .19* | .32* | |||

| 4 Openness | .18* | .14* | -.01 | ||

| 5 Neuroticism | -.34* | -.33* | -.16* | .00 |

Note. Standardized coefficients (β) are presented.

p < .05.

Figure 2.

Alcohol attitudes to alcohol use as moderated by extraversion. Graph has statistically removed all other effects from the path model.

Predicting Alcohol Myopia

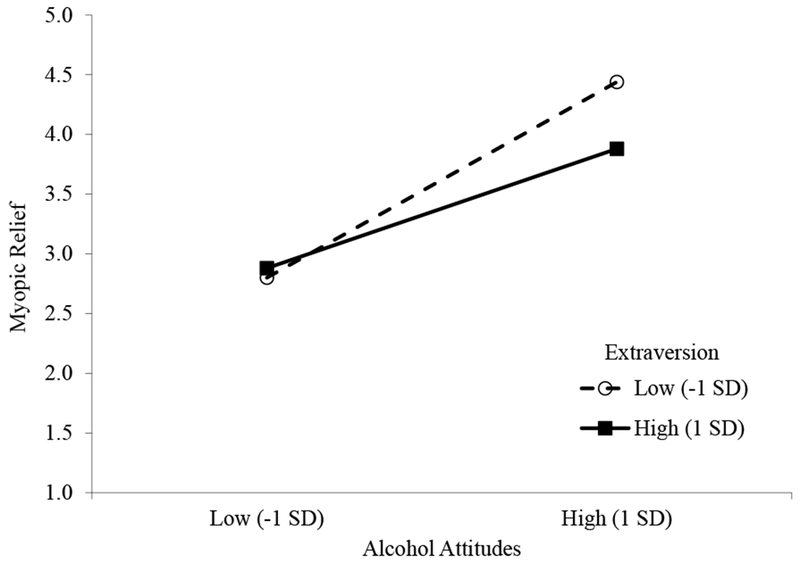

The path model results (Figure 1 and Table 2) involving predictors on the myopic outcomes of relief, self-inflation, and excess are interpreted next. Higher alcohol use, positive alcohol attitudes, higher openness, higher neuroticism, and the attitudes x extraversion interaction each statistically contributed to myopic relief. The significant interaction term is presented in Figure 3: Participants characterized by low, rather than high, extraversion were more inclined to experience myopic relief. Specifically, introverts who held favorable alcohol attitudes were more likely than extroverts who held such a view to experience tension reduction relief after ingesting alcohol. Simple slopes were significant for low (β = .46, p < .001) and high (β = .26, p < .001) extraversion.

Figure 3.

Alcohol attitudes to myopic relief as moderated by extraversion. Graph has statistically removed all other effects from the path model.

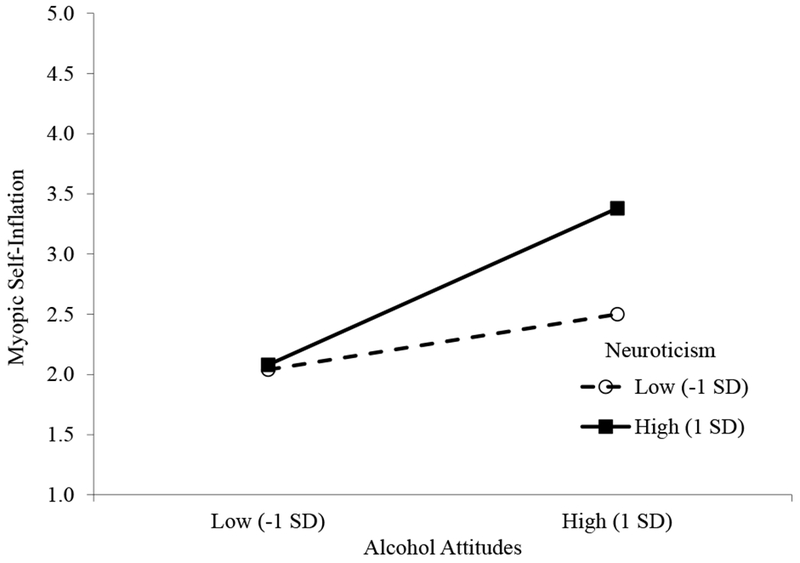

Significant predictors of myopic self-inflation included higher alcohol use, positive alcohol attitudes, lower extraversion, higher neuroticism, and the attitudes x neuroticism interaction (Figure 1). The interaction effect is graphed in Figure 4: The predictive pathway from alcohol attitudes to self-inflation was stronger in high compared to low neurotics. Thus, neurotic individuals espousing positive alcohol attitudes were more likely to exhibit myopic self-inflation. Simple slopes for high neuroticism (β = .43, p < .001) and low neuroticism (β = .15, p < .05) both attained significance.

Figure 4.

Alcohol attitudes to myopic self-inflation as moderated by neuroticism. Graph has statistically removed all other effects from the path model.

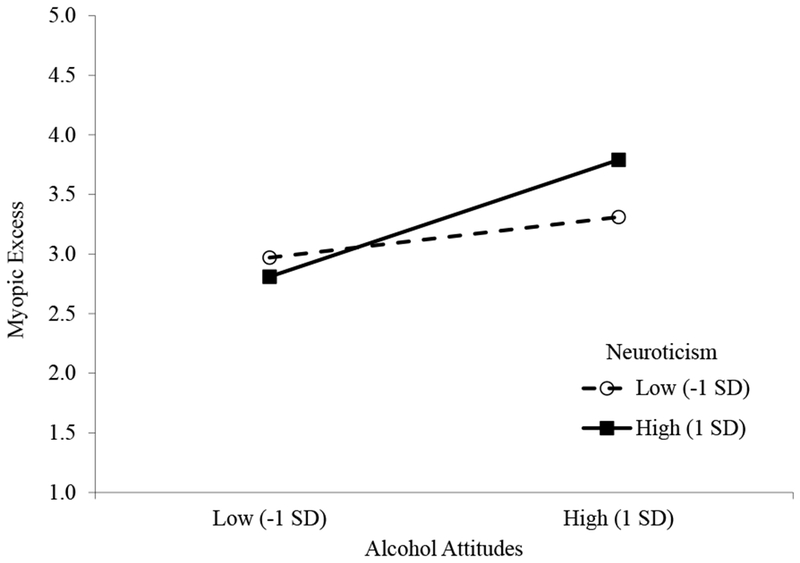

Myopic excess was predicted by higher alcohol use, positive alcohol attitudes, and the attitudes x neuroticism (Figure 1). The interaction effect is depicted in Figure 5: Favorable alcohol attitudes contributed to myopic excess in participants personified by high neuroticism, but this connection was weaker in those with low neuroticism. Highly neurotic individuals possessing high pro-alcohol attitudes were most at risk for succumbing to myopic excess. Tests of simple slopes determined that the connection from alcohol attitudes to excess in highly neurotic individuals was significant (β = .32, p < .001), but this association untenable for those low in neuroticism (β = .10, ns).

Figure 5.

Alcohol attitudes to myopic excess as moderated by neuroticism. Graph has statistically removed all other effects from the path model.

Mediational Tests

The path model in Figure 1 depicts alcohol use as mediating the connections from alcohol attitudes and personality to myopia. Thus, the traversal of pathways through the chain of variables was statistically evaluated using tests of indirect effects. The results in Table 3 determined that all possible tests of indirect effects attained statistical significance, and thereby corroborated all the mediational processes shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Tests of the Mediational Processes in Figure 1

| Predictor | Mediator | Outcome | Z test of Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Attitudes | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 4.24* |

| Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 2.30* |

| Agreeableness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 2.10* |

| Conscientiousness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 2.83* |

| Openness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 2.11* |

| Attitudes x Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Relief | 2.09* |

| Alcohol Attitudes | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 4.56* |

| Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.41* |

| Agreeableness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.10* |

| Conscientiousness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.86* |

| Openness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.23* |

| Attitudes x Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Self-Inflation | 2.09* |

| Alcohol Attitudes | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 6.40* |

| Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 2.64* |

| Agreeableness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 2.27* |

| Conscientiousness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 3.15* |

| Openness | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 2.33* |

| Attitudes x Extraversion | Alcohol Use | Myopic Excess | 2.29* |

Tests of indirect effect based on bootstrapping

p < .05.

Discussion

Alcohol myopia theory (Josephs & Steele, 1990; Steele & Josephs, 1990) postulates that alcohol’s psychoactive demands in interfering with normative cognitive processes in conjunction with personal cues produce differential myopic consequences. Analyses in the current investigation elucidated relations from alcohol attitudes and personality traits to usage and myopic relief, self-inflation, and excess. Findings offer informational resources for prevention programs designed to target alcohol attitudes and alcohol myopia by identifying the personality dispositions that serve as risk and protective factors in college students.

Several personality traits were identified in the current research as dispositional risk factors for alcohol use. Contrary to past research (Hakulinen et al., 2015; Malouff et al., 2007; Turiano, Whiteman, Hampson, Roberts, & Mroczek, 2012), higher agreeableness explained greater susceptibility to alcohol intake. A rationale is that agreeable individuals, by definition, are trustworthy, kind, tend to conform to group norms, and succumb to peer pressure, and therefore may not possess the interpersonal skills to refuse alcohol offers from persuasive others (Theakston, Stewart, Dawson, Knowlden-Loewen, & Lehman, 2004). Furthermore, extraversion served as predictor and moderator, as socially outgoing respondents with pro-alcohol attitudes were prone to greater alcohol intake (Lemos-Giráldez & Fidalgo-Aliste, 1997). This is consistent with research showing that extraverts derive more alcohol-related rewards, such as positive mood, from consumption in social settings compared to their introverted counterparts (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2006). The moderation effect indicates that favorable alcohol attitudes reinforce greater consumption in extraverted individuals who might pursue alcohol as a social lubricant to facilitate interpersonal exchanges.

The path model also determined that higher openness and higher neuroticism each uniquely served as predictors of myopic relief, defined as the temporary disconnection from preexisting stressors. Thus, people who are open to novel experiences and exhibit emotional dysregulation may be more receptive to reaching for alcohol to cope with and relieve tension and stressors. Findings support research on neuroticism and motivations for drinking (Cooper et al., 2000; Stewart & Devine, 2000; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001) by showing that neurotic individuals drink to restrict their focus and help keep their mind off persisting negative thoughts and worries. Research on the association between openness and motivations for drinking is mixed. Stewart and Devine (2000) hypothesized that openness would be associated with enhancement motives (drinking to feel better), but their results did not support this connection. However, a study conducted by Theakston et al. (2004) did reveal a significant relation between openness and enhancement motives, suggesting that those receptive to novel experiences and perspectives are prone to consume alcohol for the purpose of enhancing positive feelings. Openness to experience was the last of the five major personality traits to receive empirical support (DeYoung, 2014), and therefore additional research is needed to understand how this trait interacts with environmental cues to yield myopic effects. Furthermore, extraversion served as a moderator in the current research, as favorable alcohol attitudes were more likely to be translated into temporary relief from troubles and worries in introverts compared to extroverts. The implication is that the coveted relaxation effects of attributed to alcohol (Fromme, Stroot, & Kaplan, 1993) are most likely to be cultivated and attained by introverts who espouse positive alcohol attitudes.

Myopic self-inflation was predicted by low extraversion, high neuroticism, and the interaction of attitudes and neuroticism. People low in extraversion and high in neuroticism were found to experience self-inflated personality changes after consumption, as alcohol is shown to boost self-esteem perceptions (Glindemann, Geller, & Fortney, 1999). Previous research supports that people become more extraverted (sociable and outgoing) and less neurotic (anxious) when intoxicated (Winograd, Littlefield, Martinez, & Sher, 2012). Furthermore, a moderation effect disclosed that self-inflation perceptions tended to be exhibited in neurotic individuals who hold pro-alcohol attitudes. Neurotic individuals are prone to negative and volatile emotions (Larsen & Ketelaar, 1991), so if also espousing favorable alcohol attitudes, they might pursue this substance to regulate and enhance self-esteem (Cooper et al., 2000; Stoner, George, Peters, & Norris, 2007).

Previous research demonstrates a link between neuroticism and alcohol-related problems (Hicks et al., 2012; Ruiz et al., 2003). Consistent with this finding, alcohol attitudes and neuroticism interacted on the outcome of myopic excess. An implication is that neurotics holding positive alcohol attitudes might experience difficulties in the emotional regulation of impulses and urges when drinking, so they might be more susceptible to excessive and erratic acts including bouts of rage, engaging in fights, and damaging property (Giancola et al., 2010; Lac & Berger, 2013).

The findings in this research furnish practical insights for prevention efforts aiming to curtail alcohol use and myopic effects that can put drinkers and others in problematic situations. Programs might consider it practical to design prevention and intervention messages that simultaneously target the alcohol attitudes and personality traits of designated receivers in efforts to curtail specific types of myopic consequences. Tailored messages tend to be more efficacious than generic communications that pursue a one-size fits all approach (Hirsh, Kang, & Bodenhausen, 2012), and have yielded desirable public health outcomes (Enwald & Huotari, 2010; Rimer & Kreuter, 2006). Furthermore, understanding the personal motivations for pursuing alcohol might be an important avenue to encourage lower rates of consumption and reduce myopic consequences (Carey & Correia, 1997; Kuntsche, von Fischer, & Gmel, 2008) in programs. The contextual role of environment ought to be taken into consideration. For example, people’s motives to achieve myopic relief after a long day at work are likely disparate from their motives to foster myopic self-inflation at a social gathering. Future informational prevention and intervention programs should consider correcting preexisting belief motives that correspond to the pursuit of certain types of myopia, in efforts to attenuate drinking levels and myopic problems in various environmental circumstances.

Several limitations warrant consideration and ought to be addressed in future research. The tested pathways from alcohol attitudes (beliefs) to usage (behavior) to myopic effects (consequences) in the path model, although theoretically consistent with the literature, could be more conclusively scrutinized using longitudinal research. Future investigations applying prospective designs might verify the results of the current study and apply cross-lagged panel analysis (Lac, 2016; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002) to unravel the temporal precedence of variables. The sample consisted of college students, a cohort at high-risk for alcohol use and myopic consequences. Future investigations might cross-validate connections documented in the present study with other at-risk populations, for example, a possibility is that more pronounced relations from neuroticism to myopic excess might be ascertained in a clinical sample of alcohol abusers. Respondents were asked to recall drinking episodes and myopic effects using self-report measures. Thus, the extent that methodological discrepancies in measures of myopia for participants in sober compared to intoxicated states is warranted in future experimental research. This type of laboratory study would help to determine how manipulated factors such as level of alcohol use might impact types of myopic effects manifested (Steele & Josephs, 1990).

In conclusion, personality traits were differentially predictive of different myopia consequences. Notably, extraversion and neuroticism most frequently emerged as significant moderators in the regression models, underscoring that each of these two traits interacted with alcohol attitudes to facilitate or mitigate the risk for alcohol intake and myopia. Introverts were better able to experience relief from using alcohol compared to extroverts. Neuroticism exhibited main or moderator effects, or both, in explaining alcohol myopia. The findings in the present study are consistent with genetic research identifying that the same genetic proclivities predispose people to phenotypically exhibiting both a neurotic personality and an alcohol disorder (Grabe et al., 2011). Based on insights from the current investigation, the development of alcohol prevention and programs tailored to the type of myopia encountered is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest. The authors report no conflict of interest. This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Health—National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (L30 AA024314–01, PI: Andrew Lac).

Contributor Information

Andrew Lac, Department of Psychology, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

Candice D. Donaldson, Department of Psychology, Claremont Graduate University

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, & Ross LT (1998). Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17, 167–195. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1998.17.2.167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG, & Reno RR (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, & Roberts BW (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 887–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, & Cooper HM (1990). Effects of alcohol on human aggression: An intergrative research review. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 341–354. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.3.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2012). Structual equation modeling with mplus. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, & Correia CJ (1997). Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 58, 100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, & Abraham C (2001). Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: Toward a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1547–1561. doi: 10.1177/01461672012711014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M, Young A, Taylor D, & Bedford AP (1998). Personality correlates of alcohol consumption. Personality and Individual Differences, 24, 641–647. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00214-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, & Sheldon MS (2000). A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality, 68, 1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1995). Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the revised neo personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64, 21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, & Heiman JR (2007). Alcohol’s effects on sexual decision making: An integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JF (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG (2014). Openness/intellect: A dimension of personality reflecting cognitive exploration. APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Personality processes and individual differences, 4, 369–399. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, & Lambert LS (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JW, Bell RW, Eade R, & Underwood T (1996). ‘Alcohol myopia,’ expectations, social interests, and sorority pledge status. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Engs RC, & Hanson DJ (1994). Boozing and brawling on campus: A national study of violent problems associated with drinking over the past decade. Journal of Criminal Justice, 22, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/0047-2352(94)90111-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enwald HPK, & Huotari MLA (2010). Preventing the obesity epidemic by second generation tailored health communication: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12, 205–223. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, & MacKinnon DP (2009). A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science, 10, 87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowe HD, Stewart J, Sleath ER, & Palmer FT (2011). Public house patrons’ engagement in hypothetical sexual assault: A test of alcohol myopia theory in a field setting. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 547–558. doi: 10.1002/ab.20410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RS, McCarthy DM, Bartholow BD, & Hicks JA (2007). Interactive effects of alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol cues on nonconsumptive behavior. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15, 102–114. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot EA, & Kaplan D (1993). Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 5, 19–26. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Wetherill RR, & Neal DJ (2010). Turning 21 and the associated charge in drinking and driving after drinking among college students. Journal of American College Health, 59, 21–27. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geibprasert S, Gallucci M, & Krings T (2010). Alcohol-induced changes in the brain as assessed by mri and ct. European Radiology, 20, 1492–1501. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1668-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR (2004). Executive functioning and alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 541–555. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, & Duke AA (2010). Alcohol myopia revisited: Clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 265–278. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glindemann KE, Geller ES, & Fortney JN (1999). Self-esteem and alcohol consumption: A study of college drinking behavior in a naturalistic setting. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe HJ, Mahler J, Witt SH, Schulz A, Appel K, Spitzer C, . . . Rietschel M (2011). A risk marker for alcohol dependence on chromosome 2q35 is related to neuroticism in the general population. Molecular Psychiatry, 16, 126–128. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JA, Umstattd MR, & Usdan SL (2010). Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among collegiate women: A review of research on alcohol myopia theory. Journal of American College Health, 58, 523–532. doi: 10.1080/07448481003621718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Batty GD, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, & Jokela M (2015). Personality and alcohol consumption: Pooled analysis of 72,949 adults from eight cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 151, 110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Durbin CE, Blonigen DM, Iacono WG, & McGue M (2012). Relationship between personality change and the onset and course of alcohol dependence in young adulthood. Addiction, 107, 540–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03617.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JB, Kang SK, & Bodenhausen GV (2012). Personalized persuasion tailoring persuasive appeals to recipients’ personality traits. Psychological Science, 23, 578–581. doi: 10.1177/0956797611436349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. doi: 10.1037//1082-989x.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM (2003). Social influences in motivated drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17, 142–150. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP (1990). The ‘big five’ factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires In Pervin LA (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 66–100). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives In Pervin LA & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed.) (pp. 102–138). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Josephs RA, & Steele CM (1990). The two faces of alcohol myopia: Attentional mediation of psychological stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 115–126. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.99.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, & Watson D (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 768–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, & Engels R (2006). Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive behaviors, 31, 1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, von Fischer M, & Gmel G (2008). Personality factors and alcohol use: A mediator analysis of drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A (2016). Longitudinal designs In Levesque RJR (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (2nd ed., pp. 1–6). Switzerland: Springer International [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, & Berger DE (2013). Development and validation of the alcohol myopia scale. Psychological Assessment, 25, 738–747. doi: 10.1037/a0032535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, & Brack N (2018). Alcohol expectancies longitudinally predict drinking and the alcohol myopia effects of relief, self-inflation, and excess. Addictive Behaviors, 77, 172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Crano WD, Berger DE, & Alvaro EM (2013). Attachment theory and theory of planned behavior: An integrative model predicting underage drinking. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1579–1590. doi: 10.1037/a0030728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, & Donaldson CD (2016). Alcohol attitudes, motives, norms, and personality traits longitudinally classify nondrinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers using discriminant function analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, & Donaldson CD (2018). Testing competing models of injunctive and descriptive norms for proximal and distal reference groups on alcohol attitudes and behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, & Ketelaar T (1991). Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 132–140. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos-Giráldez S, & Fidalgo-Aliste AM (1997). Personality dispositions and health-related habits and attitudes: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Personality, 11, 197–209. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099–0984(199709)11:3<197::AID-PER283>3.0.CO;2-H [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, & Sugawara HM (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance srrucrure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, & Martineau AM (2000). Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 605–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Zanna MP, & Fong GT (1995). Decision making in altered states: Effects of alcohol on attitudes toward drinking and driving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, & Schutte NS (2007). Alcohol involvement and the five-factor model of personality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Drug Education, 37, 227–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Costa PT (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Costa PT Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509–516. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & John OP (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan JL, & Lannutti PJ (2000). Alcohol as social lubricant. Human Communication Research, 26, 175–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00755.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, & Hutchison KE (2000). Toward bridging the gap between biological, psychobiological and psychosocial models of alcohol craving. Addiction, 95, S229–S236. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8 ed.). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Hummer JF, Lac A, & Labrie JW (2014). What are other parents saying? Perceived parental communication norms and the relationship between alcohol-specific parental communication and college student drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 31–41. doi: 10.1037/a0034496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). College drinking. Special Populations and Co-occuring Disorders. from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/college-drinking [Google Scholar]

- Navarro HJ, Doran CM, & Shakeshaft AP (2011). Measuring costs of alcohol harm to others: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 114, 87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peele S, & Brodsky A (2000). Exploring psychological benefits associated with moderate alcohol use: A necessary corrective to assessments of drinking outcomes? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 60, 221–247. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW (1992). Gender patterns in consequences of collegiate alcohol abuse: A 10-year study of trends in an undergraduate population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 458–462. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW (2002). Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Schueneman AL, & Carlson K (1976). Alcohol and tension reduction: Cognitive and physiological effects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 595–2000. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.6.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, & Kreuter MW (2006). Advancing tailored health communication: A persuasion and message effects perspective. Journal of Communication, 56, S184–S201. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00289.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MA, Pincus AL, & Dickinson KA (2003). Neo pi-r predictors of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81, 226–236. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8103_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardeshmukh SR, & Vandenberg RJ (2017). Integrating moderation and mediation:A structural equation modeling approach. Organizational Research Methods, 20, 721–745. doi: 10.1177/1094428115621609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AF, Eulenbruch T, Langer C, & Banger M (2013). Interoceptive awareness, tension reduction expectancies and self-reported drinking behavior. Alcohol and alcoholism, 48, 472–477. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevincer AT, & Oettingen G (2013). Alcohol intake leads people to focus on desirability rather than feasibility. Motivation and Emotion, 37, 165–176. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9285-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, & Campbell DT (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA, US: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Kendrick A, & Maben A (1992). Use and effects of food and drinks in relation to daily rhythms of mood and cognitive performance effects of caffeine, lunch and alcohol on human performance, mood and cardiovascular function. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 51, 325–333. doi: 10.1079/PNS19920046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Josephs RA (1988). Drinking your troubles away: Ii. An attention-allocation model of alcohol’s effect on psychological stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 196–205. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Josephs RA (1990). Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist, 45, 921–933. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, & Devine H (2000). Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, & Rhyno E (2001). Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain—drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 271–286. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00044-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner SA, George WH, Peters LM, & Norris J (2007). Liquid courage: Alcohol fosters risky sexual decision-making in individuals with sexual fears. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 227–237. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9137-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston JA, Stewart SH, Dawson MY, Knowlden-Loewen SAB, & Lehman DR (2004). Big-five personality domains predict drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 971–984. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2003.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turiano NA, Whiteman SD, Hampson SE, Roberts BW, & Mroczek DK (2012). Personality and substance use in midlife: Conscientiousness as a moderator and the effects of trait change. Journal of research in personality, 46, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, & Bentler PM (2003). Structural equation modeling In Schinka JA & Velicer WF (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (pp. 607–634). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, & Abrams D (1977). Effects of alcohol on social anxiety and physiological arousal: Cognitive versus pharmacological processes. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1, 195–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01186793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd RP, Littlefield AK, Martinez J, & Sher KJ (2012). The drunken self: The five‐factor model as an organizational framework for characterizing perceptions of one’s own drunkenness. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research, 36, 1787–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe WL, & Maisto SA (2000). The effect of self-discrepancy and discrepancy salience on alcohol consumption. Addictive behaviors, 25, 283–288. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]