Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the effects of observation-based supervision (BOOST therapists = 26, families = 105), versus supervision as usual (SAU therapists = 21, families = 59) on a) youth externalizing behavior problems and b) the moderating effects of changes in family functioning on youth externalizing behaviors for adolescents receiving Functional Family Therapy (FFT). Exploratory analyses examined the impact of supervision conditions on youth internalizing problems.

Method:

In 8 community agencies, experienced FFT therapists (M = 1.4 years) received either BOOST or SAU supervision in a quasi-experimental design. Male (59%) or female (41%) adolescents were referred for the treatment of behavior problems (e.g., delinquency, substance use). Clients were Hispanic (62%), African American (19%), Non-Hispanic White (12%) or Other (7%) ethnic/racial origins. Therapists (female, 77%) were Hispanic 45%, African American (19%), White Non-Hispanic (30%) or other (4%) ethnic/racial backgrounds. Analyses controlled for the presence or absence of clinically elevated symptoms on outcome variables. Clinical outcomes were measured at baseline, 5-months, and 12-months after treatment initiation.

Results:

Clients with externalizing behavior above clinical thresholds had significantly greater reductions in problem behaviors in the BOOST versus the SAU conditions. Clients below thresholds did not respond differentially to conditions. Supervisors in BOOST had more experience with the FFT model; as such, the observed results may be a result of supervisor experience.

Conclusion:

The BOOST supervision was associated with improved outcomes on problem behaviors that were above clinical thresholds. The findings demonstrate the importance of addressing client case mix in implementation studies in natural environments.

Keywords: Family therapy, case mix, supervision, externalizing, implementation

Functional Family Therapy (FFT; Alexander & Parsons, 1982; Alexander, Waldron, Robbins, & Neeb, 2013) is an evidence-based treatment for adolescent delinquency and substance use (Robbins, Alexander, Turner, & Hollimon, 2016). FFT has been widely disseminated into community settings producing significant improvements for youth with behavior problems (Baglivio, Jackowski, Greenwald, & Wolff, 2014; Barton, Alexander, Waldron, Turner, & Warburton, 1985 [Study 1, 2]; Celinska, Furrer, & Cheng, 2013; Hansson, Johansson, Drott-Englén, & Bendery, 2004). Studies have also shown that FFT is effective in improving a) youth internalizing symptoms (Celinska et al., 2013; Hansson et al., 2004) and b) parent internalizing symptoms/distress (Hansson et al., 2004). Recent studies have yielded mixed findings with respect to adolescent gender, with one study showing that girls may have responded more favorably to FFT (Baglivio et al., 2014) and another showing that no differences in outcomes based on youth gender (Celinska & Cheng, 2017).

The transportation of evidence-based treatments (EBTs), such as FFT, into practice settings has yielded mixed results, with some estimates suggesting that the outcomes observed in controlled efficacy trials diminished by as much as 50% (Henggeler, Pickrel, & Brondino, 1999). The successful implementation of EBTs and the subsequent achievement of positive outcomes in effectiveness trials are intrinsically linked. Hence, the need to identify the parameters for successful implementation is widely recognized (Bertram, Blasé, & Fixsen, 2015; Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003; Kazdin, 2008).

A major determinant of successfully transporting EBTs into community settings is the integrity of implementation (Fixsen et al., 2005; Glasgow et al., 2003). One of the single most significant challenges associated with implementation integrity is sustaining treatment fidelity through therapists’ “competent adherence” to the treatment model (Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2005; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Liao, Letourneau, & Edwards, 2002; Mihalic & Irwin, 2003). Given adequate therapist training, ongoing supervision is the key element for sustaining model fidelity in community agencies (Fixsen et al., 2005; Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Chapman, 2009).

Based on the accumulated evidence supporting FFT, interest in disseminating the FFT treatment model has skyrocketed. Currently, the dissemination organization, FFT LLC (www.fftllc.com), has trained more than 400 local, state, national and international organizations. Annually, over 2500 FFT therapists served nearly 60,000 families around the globe. To address the key issue of enhancing treatment competence, FFT LLC developed and implemented a web-based application to monitor highly structured FFT therapist progress notes, as well as supervisor and client ratings of therapist competence. The process helps to maximize sustainability for community programs by limiting costs. The impact of this supervision process on therapist competence and treatment outcomes is unknown.

By contrast, Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez and Pirritano (2004) found that supervision involving active feedback and/or coaching based on supervisor review of therapy sessions to observe therapist behaviors directly results in improved model fidelity. Such observation-based supervision has been the hallmark in the development of family therapy models and in fidelity monitoring processes in efficacy trials evaluating family therapy (Crits-Christoph et al., 1998; Forgatch et al., 2005). By eliminating this practice, it is possible that FFT dissemination efforts may have unwittingly omitted an important component needed for effective transfer of treatment.

Supervision in Family Therapy

Early meta-analyses found two factors predicting better client outcomes in child and adolescent psychotherapy (Weisz, Donenberg, Han, & Kauneckis, 1995). The first was the use of formally developed treatment manuals specifying which therapist behaviors were to be implemented. A second was the presence of ongoing monitoring of therapists using session tapes. Within the rich family therapy tradition of training and supervision (see Liddle, 1991; Storm, McDowell, & Long, 2003), the use of cutting-edge teaching strategies and methods (e.g., live supervision, videotapes) has long been a standard. Supervision has typically included (a) direct review of cases using recordings, (b) on-site, live supervision with the therapists/trainees’ actual cases, and (c) externships where therapists receive intensive training with cases under the direct supervision of a clinical team. Across training programs, the central focus is to ensure that therapists are not only capable of effectively implementing EBTs, but that they are also able to maintain fidelity over time. With respect to the latter, ongoing supervision is a key aspect of training and is considered to be a critical ingredient of successful transportation to community agencies. In fact, research indicates that when supervision is withdrawn, therapist adherence and clinical outcomes deteriorate over time (Henggeler et al., 1999).

The successful dissemination of family therapy to community agencies includes intensive training, individual and group supervision led by an expert in the model, and monitoring procedures (e.g., Schoenwald et al., 2009). In most respects, the supervision in dissemination parallels the process of supervision that is standard in treatment development studies and efficacy trials evaluating family therapy and addictions treatments (Crits-Cristoph et al., 1998; Forgatch et al., 2005; Liddle, Dakof, Turner, Henderson, & Greenbaum, 2008; Santisteban et al. 2003). However, one difference between supervision in the dissemination of FFT and in clinical efficacy studies is the use of observational procedures as a mechanism for maintaining therapist fidelity. By eliminating this practice, community dissemination projects may unwittingly be omitting one of the most important components needed for effective transfer of treatment.

The goal of observation-based supervision is to ensure supervisors provide feedback to therapists based on the supervisors’ direct judgments about therapist in-session behaviors and family needs, rather than therapist self-report of session activities and interactions alone, which can be limited by memory distortion, selective reporting, omissions in the delivery of key elements of the intervention not detected by therapists, and other factors that render therapists less-than-optimal reporters of their own behavior and session events (Bergin & Garfield, 1994; Bickman, 2008). By listening to actual therapist utterances, the supervisor is able to tailor feedback to the characteristics each therapist, as well as to the unique characteristics of each family.

As evident from this description, supervision is an essential element of family therapy. To date, however, studies examining the impact of supervision on therapist fidelity and clinical outcomes have been rare. During this early period of research on dissemination, it is vital to identify the specific procedures that are most likely to maximize effective translation of efficacious treatments into community settings. Because the development of family therapy practices and efficacy trials have relied heavily on observation-based supervision to achieve positive youth outcomes, a key first step is to examine the extent to which supervision relying on observation of therapist behaviors during sessions, as opposed to relying solely on therapist self-report, influences therapist competence. Given that supervision is the primary mechanism utilized to maintain fidelity, it is possible that an observation-based supervision approach will improve outcomes as well, as proposed in the current study.

Finally, researchers have summarized evidence indicating that less than 50% of therapists in community practice settings deliver evidence-based practices with fidelity after they complete training (Wiltsey-Stirman et al., 2015, Miller et al., 2004). Therapists in these settings report that they make modifications either to the content or to the delivery methods of the standard practice for which they received training. Wiltsey-Stirman et al. (2015) classify these modifications as fidelity consistent or inconsistent adaptations. A fidelity consistent adaptation may include the tailoring of interventions to the client, the addition of modules to address unique problems of the client, or extending the duration of treatment. Model inconsistent adaptations may include the deletion of key components of the intervention, shortening the duration of treatment, or incorporating elements from alternative clinical models that have not been tested in combination with the evidence-based model. From an FFT perspective, the tailoring of interventions to specific risk factors is an inherent aspect of the clinical model, and supervision is essential for ensuring that therapists implement the model with high fidelity. Thus, the focus of this study was to examine if outcomes are enhanced by adding observation-based strategies, delivered by expert supervisors, to the standard, to the supervision process of therapists in real world settings.

Current Study

The purpose of the proposed study was to examine the effects of observation-based supervision (BOOST) versus the standard supervision as usual (SAU) approach currently used by FFT LLC on therapist competence and adolescent/family outcomes in a community-based sample of adolescents receiving FFT. The study was implemented with 12 FFT teams of experienced FFT therapists affiliated with the California Institute of Behavioral Health Services, the coordinating center for stakeholders implementing FFT in community agencies in California. The aims of the study were to determine if the BOOST condition, compared to SAU, was associated with greater improvements in (a) adolescent externalizing behavior problems and (b) the moderating role of family functioning on youth externalizing behaviors. With respect to the first aim, adolescents were classified as above clinical threshold or below clinical threshold on externalizing disorders to examine if observation-based strategies are most effective for clients that are most likely to draw therapists off model. Exploratory analyses examined the differential effectiveness of BOOST vs. SAU on youth internalizing behaviors. Based on research showing the relevance of adolescent gender in FFT (Baglivio et al., 2014; Celinska & Cheng, 2017), youth gender was included as a key variable in all analyses.

Method

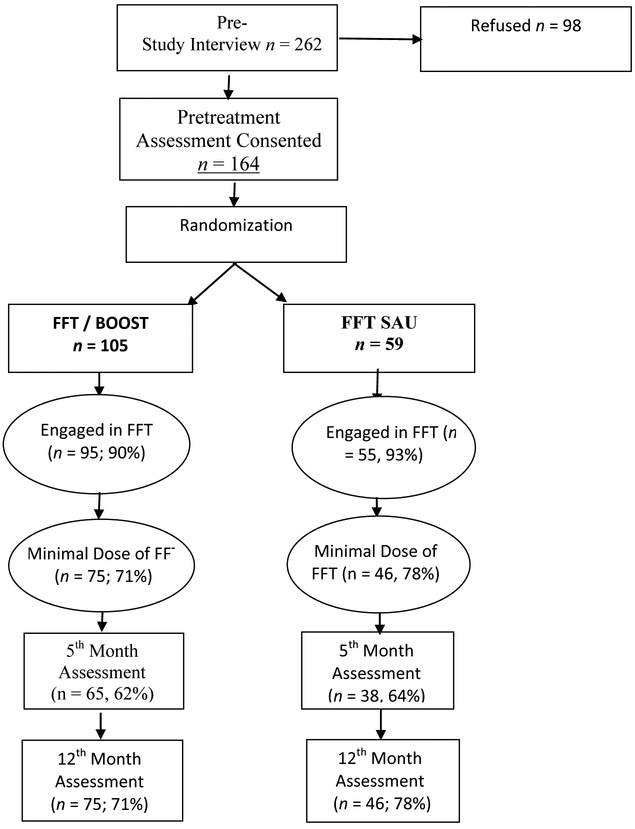

All study procedures were completed following the procedures approved by the IRB where both principal investigators are affiliated. Local IRB approvals were obtained from county mental health and juvenile justice departments, and participating sites. Figure 1 presents the case flow through the experiment.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Through the Study

Enrollment and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Enrollment Procedures.

Research assistants completed screening, consent, and enrollment procedures in coordination with site intake staff. Adolescent and family members provided informed assent/consent prior to participating in any study-related activities. Adolescents met the following inclusion criteria: (1) had at least one parent or parent figure (i.e., step-parent or surrogate) willing to participate; (2) were 10 to 18 years of age (inclusive); (3) living at home with the participating parent; and (4) had sufficient residential stability to permit probable contact at follow-up (e.g., not homeless at intake). Exclusion criterion was: (1) evidence of psychotic or organic state of sufficient severity to interfere with understanding of study instruments and procedures, (2) evidence of psychotic or organic state of sufficient severity to interfere with understanding of study instruments and procedures and (3) a sibling participating in the study.

Therapist participants were recruited from participating sites. Therapists were eligible to participate if they had completed a requisite course of clinical training and supervision in FFT, had an active FFT caseload, and were participating in weekly group and individual supervision. All therapists had extensive training in FFT, including review of the clinical training manual and directed readings and workshops that included lecture and slide presentations, interactive discussion, review of recorded therapy sessions, and role-play rehearsal. Prior to enrollment, therapists typically had 1–2 years of FFT experience, although two clinicians were still in their first year of training.

Participant Characteristics

Adolescent / Family Participants.

The sample included 164 youth (60% male, 40% female) and their families. The youths ranged in age from 10.9 to 18.0 years (M = 14.95, S. D. = 1.65). Youth/families self-identified as Hispanic (61.6%), White, non-Hispanic (12.2%), African American (18.9%), Native American (3.7%), Asian (1.2%) and other (2.4%).

Therapist Participants

The sample included 47 therapists from 12 community agencies. The therapist sample was predominately female (77%), and 21 self-reported as Hispanic, 14 as White, non-Hispanic, 9 African American, and 2 other. There were no differences in age, years of experience, or educational status in therapists between BOOST and SAU sites. The majority of therapists were experienced with the FFT model, with most having worked with more than 50 cases. Also, analyses of pre-study FFT experience and fidelity showed high comparability between therapists from the two conditions prior to seeing study cases.

Supervisors

SAU supervision was completed by a member of the site team who met FFT LLC’s supervisor criteria. This included at least one year of experience conducting FFT with high fidelity, completion of a clinical externship in FFT, attendance at four days of supervisor training, bi-monthly calls for at least one year with an FFT LLC consultant, and ongoing monthly calls after the first supervisory year. The typical SAU supervisor had provided guidance for the treatment of more than 150 families. The present study included 6 supervisors (5 female; 1 male) from 5 SAU teams. SAU supervisors were non-Hispanic, White (n = 2), Asian (n = 2), Hispanic, White (n = 1), or African American (n = 1). All supervisors had a Master’s degree and between 1 and 5 years’ experience.

BOOST supervision was completed by 5 investigators and staff (4 female, 1 male) affiliated with the primary research facility. The BOOST supervisors were non-Hispanic White (n = 4) or Hispanic, White. Three of the BOOST supervisors had Ph.D.’s and two were Master’s-level. The Ph.D. level supervisors conducted the supervision for the majority of BOOST cases. The years of experience for BOOST supervisors ranged from new supervisors (Master’s-level) to 22 years. The Ph.D. level supervisors averaged more than 20 years of experience with the FFT model.

FFT Treatment: Received by Youth in Both BOOST and SAU

Adolescents and family members in both conditions received FFT (Alexander & Parsons, 1982; Alexander et al., 2013). FFT is applied in five distinct phases: Engagement, Motivation, Relational Assessment, Behavior Change, and Generalization. Each phase has associated specific goals, techniques, and important therapist relationship and structuring skills. In the first two phases, the focus is on establishing credibility to engage family members into treatment, and then to address within family negativity, blame and hopeless to motivate family members into a process of change. The third phase involves the assessment family interactions and functional aspects of behaviors, attributions, and feelings of family members and extra-familial significant others. This assessment sets the stage for designing and implementing the behavior change phase. The behavior change phase involves training and applying maintenance technology (e.g., parent-child communication training, behavioral contracting). Skills training interventions such as problem-solving and other behavioral intervention strategies are included using a menu-driven process from the behavior therapy literature (e.g., listening skills, anger management, parent-directed behavioral consequences, improved parental supervision).

A unique feature of FFT is the specific focus on skills in the context of assessed relational functions of behavior (e.g., separation, contact) within each dyad of the family system. The focus of change is on replacing maladaptive behaviors used to maintain relationship functions. Readiness for therapy termination is based on the family demonstrating the generalization of new skills and behaviors in the home and environment outside the therapy session, the maintenance of treatment gains, and the ability to function independently from the therapist. All FFT therapy sessions were audio recorded for therapist supervision and evaluation of treatment adherence.

Supervision Conditions

Supervision as Usual (SAU).

SAU represented the standard supervision approach currently implemented by FFT LLC. As noted above, all supervision in SAU was conducted by an on-site supervisor who had extensive experience as an FFT therapist and site lead. SAU consisted of a 1-hour weekly group supervision session with the clinical team (typically 3–6 therapists). In addition, the on-site supervisor conducted individual supervision sessions with each member of the clinical team. As such, each therapist received two hours of supervision per week. Group supervision sessions involved the following: a) review of cases, b) guided discussions of key concepts and implementation issues in which the supervisor provided support to therapists, identified adherence components, taught and modeled intervention strategies, and assistance in developing treatment plans, c) role play/rehearsal of therapeutic interventions and strategies. Individual supervision covers the same areas but was tailored to the unique strengths, weaknesses, and personal characteristics of the therapist.

All SAU supervision sessions were guided by information that therapists entered into a web-based Clinical Service System (CSS; www.fftllc.com). This web-based system includes information about demographics, referral problems, and risk and protective factors as well measures for tracking all clinical contacts with family members. Detailed progress notes are completed for each session to identify the goals, interventions used, and family responses. Progress notes are specific to each phase of the FFT model (e.g., Motivation, Behavior Change, Generalization). SAU supervisors use these notes to review cases and plan next steps with therapists. The CSS system also includes detailed reports that are useful to track case progress (e.g., time from referral to first session, length of service) and outcomes (e.g., dropout, completed, youth remained in home, arrests).

BOOST.

The BOOST (Building Outcomes with Observation-Based Supervision of Therapy) supervision model was developed and refined in the course of implementing numerous NIH-funded clinical trials. The fundamental distinction between BOOST and SAU is the use of direct observation, via audio recordings of therapy sessions, to guide supervision. In addition, the BOOST therapist received supervision on every session; whereas, in SAU only a portion of all sessions are discussed in supervision sessions. BOOST incorporated: 1) audio recording of all therapy sessions; 2) therapist and supervisor review of the recorded therapy sessions prior to and/or during supervision; 3) weekly supervision meetings.

As noted above, BOOST supervision was provided by experts from the research team. Each week therapists submitted recordings of therapy sessions for every BOOST case that was seen in treatment via a secure internet site. The BOOST supervisor reviewed these sessions, developed notes, sent the notes to therapists, and then met by telephone with the therapist and their on-site supervisor to review sessions. Only BOOST therapists attended BOOST supervision sessions.

The goal of BOOST was to ensure supervisors provide feedback to therapists based on the supervisors’ direct observations of recordings of therapist and family behaviors rather than relying solely on therapist self-report of session activities and interactions. Since the BOOST supervisor reviewed each therapist’s recordings, it was expected that they would be more likely to identify which sessions should be the focus of greater supervision time and attention, making the supervision session more useful and constructive for the therapist. By listening to actual therapist utterances, the supervisor was able to provide feedback to the therapist at a much more refined level, likely increasing therapist clinical skills much more quickly than would be possible with only general information about the therapists’ in-session behaviors. In addition, the BOOST supervisor is able to tailor the feedback in a manner that is more sensitive to the unique characteristics of each family.

BOOST retained the same basic structure as SAU. To maximize the feasibility of implementation in real world settings, the time therapists spend in supervision in BOOST was the same as in SAU. BOOST consisted of up to an hour of individual supervision weekly. The on-site supervisor was included in the supervision meetings with other therapists to minimize disruption of normal staff relationships during the BOOST intervention. Supervision of clients who were unilingual Spanish-speaking was carried out by a Spanish-speaking supervisor or with the assistance of interpreters. It should be noted that BOOST supervisors spent considerably more time preparing for supervision sessions than SAU supervisors because all session recordings were reviewed for study cases. For example, the preparation time for a typical group supervision session in SAU was approximately one hour (for all cases on the team). In contrast, each session in BOOST took approximately 1.25 hours to review and prepare detailed feedback.

Measures

Assessments were conducted at baseline and at 5- and 12-months after treatment initiation. The 5-month assessment was selected to estimate potential end of treatment effects based on the average length of service of FFT in California. Assessments were administered via computer, using an audio-enhanced computer-assisted self-administered interviews (ACASI) format that was offered in English and Spanish. Adolescents and parents were remunerated with a gift card for their time in completing study assessments ($15 at baseline, $20 at 5-months, and $40 at 12-months). The following assessments were used in the current study.

A general demographic questionnaire was used to capture information from youth and parents about age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, parent marital status, and information about the adolescent’s current living status (e.g., family composition/type, family household income, who lives in the home, and family roles).

Externalizing and Internalizing problems were assessed using the CBCL and the YSR (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL/YSR is a 113-item scale that provides a standardized format to elicit reports of youths’ externalizing and internalizing problems. For adolescent externalizing behaviors, the current analyses uses a composite score calculated from the Rule Breaking and Aggression subscales. The internal consistency for the externalizing composite was alpha = .784 and .788 for parent and youth report, respectively. Composite scores were created and analyzed separately for youth and parents. The current analyses used the broad internalizing scale to capture adolescent internalizing behaviors. The internal consistency for the internalizing composite was alpha = .843 and .833 for parent and youth report, respectively. Scores for youth and parents were analyzed separately. In addition, information about adolescents’ prior criminal activities was obtained with the Legal Problems Questionnaire, based on the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992). Questions asked about the frequency of each of 39 criminal behaviors in his or her lifetime and in the previous 3 months. Scores for Felony and non-Felony offenses were used in an exploratory analysis.

Family functioning was assessed using the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986). Analyses used a composite score created from the cohesion, conflict, and organization subscales. The internal consistency for the family composite was alpha = .825 and .815 for parent and youth report, respectively. Separate analyses were conducted for youth and parents.

Results

Overview of the statistical analysis

The presence of missing data was assessed for possible attrition bias. No significant differences between conditions were observed on any variable at baseline. For key dependent variables, missing data were replaced to form 10 complete data sets through multiple imputation procedures (Graham, 2012). A set of baseline conditioning variables was used to improve the estimates. The conditioning variables from baseline assessments were adolescent gender, age, externalizing and internalizing scores from the YSR and CBCL, adolescent FES composite, and indicators for Hispanic or African American race/ethnic origin.

The first step in the analytic plan was to examine baseline data to identify variability in reports of adolescent externalizing and internalizing behaviors (i.e., case mix). Based on the results of the first step, we then examined differences between supervision conditions (BOOST vs. SAU) on adolescent externalizing problems. Given the representation of a relatively large proportion of adolescent girls (40%), we included adolescent gender as a key variable. The third step involved examining the extent to which changes in family functioning accounted for improvements in adolescent externalizing behaviors. Finally, in the fourth step, we conducted an exploratory analysis to examine the differential impact of supervision condition on youth felony and non-felony offending. The tests of significance in youth externalizing (step 1) and internalizing (step 4) behaviors were designed to capture clinically meaningful levels of problems. In doing so, however, the focus was on examining youth above or below the clinical threshold for these scales. For ease of interpretation, we provide estimates of effect sizes to display the strength of effects in changes from baseline to the end of treatment, and overall change from baseline to the end of the follow-up period.

Assessing the Presence of Complex Case Mix at Baseline

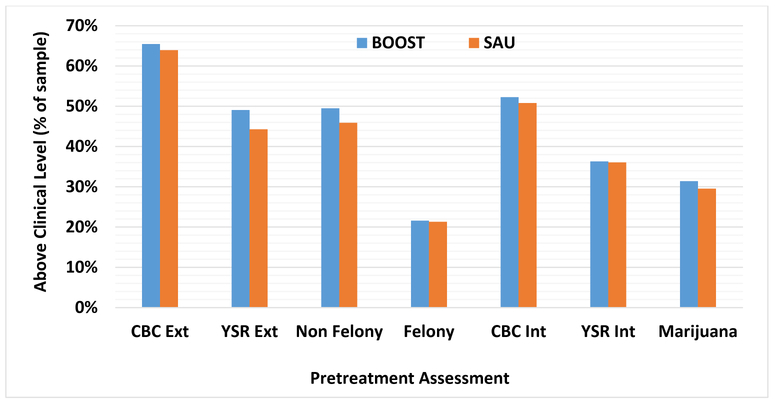

In contrast to efficacy trials where a stringent set of inclusion/exclusion criteria is used to define the sample, the current study adopted a strategy that was intended to capture the range of cases typically seen in community settings. This strategy potentially increases the relevance of results to community practitioners, but it creates analytical challenges because cases are referred to treatment for a variety of issues. Thus, the challenge in interpreting analyses that include the full sample is that potential effects for a particular problem are diluted because all youth are included in the analysis, irrespective of whether or not they presented with a specific problem at baseline. For example, as shown in Figure 2, there was significant variability in youth and parents reports at baseline. Some cases presented with a mix of problems, some with only an externalizing problems, and some with only an internalizing problem.

Figure 2.

Percent of clients in the SAU and BOOST conditions above clinical thesholds for indicators.

Note: Ext = Externalizing, Int= Internalizing; CBC = Child Behavior Checklist’ YSR = Youth Self-report, Mar = any marijuana; Felony = any felony.

In the present paper, we restricted the primary focus to adolescent externalizing problems because it was the most consistent problem observed in this sample. Also, although the rate of youth criminal offending was relatively low, we included reports of criminal behavior to provide a more thorough presentation of externalizing problems. Finally, we included an exploratory analysis to examine adolescent internalizing disorders. Due to the lower rate of internalizing observed in this sample, we restricted this to an exploratory comparison.

For all analyses, we conducted an initial inferential test of statistical significance on each dependent variable to evaluate whether differences might be attributable to random sampling variation. Next, we used descriptive statistics to evaluate the impact of treatments on subsets of clients presenting with different combinations of risk dimensions. For example, we assessed whether the clients had scores above clinical thresholds on measures with established clinical norms. In addition, we included effect size estimates rather than relying solely on tests of statistical significance. Judgments based upon statistical tests are dependent upon the sample size used in comparisons. We reasoned that the utility of the findings would depend upon the relative size of an effect that practitioners might expect to occur in community settings regardless of the sample size. We calculated estimates using the baseline standard deviation to scale the effect size to the naturally occurring differences among clients as they entered treatment.

Basic Design

The current research represents a Stage III effectiveness trial to examine the effects of observation-based supervision (BOOST) versus SAU in the implementation of FFT with a community-based sample of adolescents referred to community mental health clinics. The research design is a 2 (Supervision Condition: BOOST or SAU) x 3 (Time: baseline, 5 months, 12 months) factorial design. Three additional independent variables are hierarchically nested (multilevel) factors within Supervision Condition: (a) Families are nested within each therapist, and Therapists are nested within each of 12 Therapist Teams in 8 community agencies. FFT therapist teams (k =12) were randomly assigned either to BOOST or SAU. The Team, Therapist, and Family variables are random effects factors; Time is a fixed effect, repeated measures factor. The analysis addressed multilevel nesting effects and used covariates shown to be effective in controlling for nesting of families within therapists and therapists within teams.

Adolescent Problem Behaviors

Externalizing behavior: youth self-report.

We examined changes in the adolescents’ (YSR) externalizing behavior by conducting a 2 (Condition: SAU, BOOST) x 2 (Gender: Female, Male) x 3 (Time; Baseline, 5 months, 12 months) factorial repeated measures analysis of variance with the YSR Externalizing composite as the dependent variable. We performed the analyses separately for clients whose baseline self-reported externalizing behavior was above or below the clinical threshold. The analyses used all 10 imputed data sets but statistical values were adjusted to correspond to the original sample size (SAU female n = 27; male n = 31; BOOST female n = 40; male n = 65).

The results indicated that none of the effects were statistically significant [F’s < 1.68, p > .19, η2 < 0.020] for clients who were below the clinical threshold at baseline. The results for clients above threshold revealed statistically significant main effects for Condition [F(1,77) = 6.00, p < .017, η2 = 0.073] and Time [F(1,153) = 18.36, p < .001, η2 = 0.193]. The Condition x Gender x Time interaction [F(1,153) = 3.24, p < .042, η2 = 0.041] was also statistically significant but the other effects were not statistically significant [F’s < 1.65, p > .195, η2 < 0.021]. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the clients above and below threshold at each assessment by condition. We also computed the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for change from baseline to the 5th month and the 12th months among clients above and below threshold in each supervision condition. For clients that presented above clinical thresholds at intake, the effect size estimates of change from baseline to 12-months were very large for clients in both conditions; however, the changes were larger in the BOOST condition (d = 1.376) than the SAU condition (d = 0.767). In contrast, the changes in clients initially below thresholds were quite small in both conditions. The change analysis from baseline to 12 months suggests that the differential effects of BOOST occurred primarily for males (BOOST d = 0.92, SAU d = 0.12) but not for females (BOOST d = 0.66, SAU d = 0.79).

Table 1.

Effects of supervision condition on youth self-reported externalizing (YSR) for clients above and below clinical thresholds at baseline assessments.

| Condition × YSR Externalizing Clinical Threshold |

Assessment Point | Effect Size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline M (SD) |

5 Months M (SD) |

12 Months M (SD) |

t0 to t5 | to t12 | |

| SAU-Below (SB) | 7.72 (4.24) | 6.95 (6.05) | 7.87 (6.67) | 0.18 | −0.04 |

| BOOST Below (BB) | 7.29 (4.07) | 6.68 (4.46) | 8.24 (6.60) | 0.15 | −0.23 |

| SAU Above (SA) | 24.16 (5.05) | 22.11 (9.20) | 20.28 (9.50) | 0.41 | 0.77 |

| BOOST Above (BA) | 23.02 (5.64) | 17.86 (8.17) | 15.26 (8.04) | 0.91 | 1.38 |

| d = (SB- BB) | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.20 |

| d = (SA – BA) | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.53 | −0.51 | −0.61 |

Note: Cell entries are the means (M) or standard deviations (SD) for the externalizing measure. The effect size estimates are based upon Cohen’s d criteria and compare change from baseline (t0) to the fifth (t5) or the 12th (t12) month. The bottom rows reports the effect size differences between the SAU and BOOST conditions at each assessment point for clients that are either above (A) or below (B) the clinical threshold. The baseline sample sizes were SB = 33; BB = 54; SA = 26; BA = 51.

Externalizing behavior: parent report.

We repeated the analysis using the parent report of the youth’s externalizing behavior (CBCL) as the dependent variable (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of supervision condition on parent report of youth externalizing (CBCL) for clients above and below clinical thresholds at baseline assessments.

| Condition × CBCL Externalizing Clinical Threshold |

Assessment Point | Effect Size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline M (SD) |

5 Months M (SD) |

12 Months M (SD) |

t0 to t5 | to t12 | |

| SAU-Below (SB) | 7.13 (3.88) | 6.23 (7.27) | 5.60 (6.36) | 0.20 | 0.34 |

| BOOST Below (BB) | 8.94 (4.62) | 8.19 (7.26) | 7.80 (8.42) | 0.17 | 0.26 |

| SAU Above (SA) | 27.09 (8.26) | 18.36 (11.44) | 22.34 (14.86) | 0.99 | 0.54 |

| BOOST Above (BA) | 27.80 (9.07) | 19.71 (10.62) | 21.37 (14.02) | 0.92 | 0.73 |

| d = (SB- BB) | −0.41 | −0.44 | −0.49 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| d = (SA – BA) | −0.08 | −0.15 | 0.11 | 0.07 | −0.19 |

Note: Cell entries are the means (M) or standard deviations (SD) for the externalizing measure. The effect size estimates are based upon Cohen’s d criteria and compare change from baseline (t0) to the fifth (t5) or the 12th (t12) month. The denominator was the baseline composite for clients below (SD = 4.46) or above (SD = 8.79) clinical thresholds. The bottom rows reports the effect size differences between the SAU and BOOST conditions at each assessment point for clients that are either above (A) or below (B) the clinical threshold. The baseline sample sizes were SB = 21; BB = 37; SA = 38; BA = 68.

The results for clients below clinical thresholds on the CBCL indicated that none of the effects were statistically significant [F’s <1.38, p > .25, η2 < 0.024]. The results for clients above the clinical thresholds revealed a statistically significant main effect for Gender [F(1,105) = 7.11, p < .009, η2 = 0.063], Time [F(2,210) = 33.43, p < .001, η2 = 0.241], Condition x Gender [F(1,105) = 4.60, p < .03, η2 = 0.042], Time x Gender, F(2,210) = 4.10, p < .018, η2 = 0.037] and Time x Condition x Gender F(2,210) = 4.66, p < .010, η2 = 0.042]. The effect size results for the change from baseline to the 5th month indicates a strong effect size in both conditions but with the greatest change occurring for males in the SAU condition (d = 1.62). However, at the 12th month, the SAU females appear to experience relapse (d = −0.12) while the males continue to demonstrate a large effect size change.

Effects of Condition and YSR Externalizing on changes in adolescent FES scores.

We conducted a preliminary analysis to determine whether the clients above or below the YSR externalizing thresholds differed in their family relationships at baseline. This comparison indicated that clients above the clinical threshold had significantly [F(1,163) = 40.55, p < .001, η2 = 0.199] worse family relationships (M = 5.20, S.D. = 2.00) than clients below the threshold (M = 6.91, S.D. = 1.38). Since we anticipated that the supervision conditions would have different effects depending upon the client’s externalizing behavior, we conducted separate analyses for clients above and below the clinical thresholds.

We conducted a 2 (Condition: BOOST, SAU) x 2 (Gender: Female, Male) x 3 (Time: baseline, 5-month, 12-month) factorial repeated measures analysis of variance using data from all 10 imputed sets for clients above or below the YSR clinical threshold. All of the effective sample sizes were adjusted to be equivalent to the baseline sample sizes (BOOST female n = 40, male n = 65; SAU female n = 27; male n = 31).

The results of the ANOVA for clients below the clinical threshold indicated that none of the effects was statistically significant [F’s < 2.22, p > .11, η2 < .03] and the change effect sizes reflected minimal positive changes in the family environment (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of supervision condition on adolescent reported family environment moderated by clients above or below YSR externalizing clinical thresholds at baseline assessments.

| Condition × YSR Externalizing Clinical Threshold |

Assessment Point | Effect Size d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5th Month | 12th Month | t0 to t5 | to t12 | |

| M SD | M SD | M SD | |||

| SAU Below (SB) | 6.70 (1.35) | 7.03 (1.45) | 6.31 (2.32) | −0.25 | 0.29 |

| BOOST Below (BB) | 7.04 (1.38) | 6.97 (1.66) | 7.08 (1.67) | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| SAU Above (SA) | 4.68 (2.18) | 4.90 (1.84) | 5.43 (2.53) | −0.10 | −0.34 |

| BOOST Above (BA) |

5.46 (1.87) | 6.32 (1.92) | 6.38 (1.82) | −0.46 | −0.50 |

Note: Cell entries are the means (M) or standard deviations (SD) for the adolescent family environment measure. The effect size estimates used Cohen’s d criteria and compared change from baseline (t0) to the fifth (t5) or the 12th (t12) month. Clients that are either above (A) or below (B) the YSR clinical threshold. The baseline sample sizes were SB = 33; BB = 54; SA = 26; BA = 51.

The results for clients above the clinical threshold revealed statistically significant main effects for Condition [F(1, 77) = 9.78, p < .001, η2 = 0.113], Time [F(2, 154) = 6.48, p < .001, η2 = 0.078], and the Condition x Gender interaction [F(1, 77) = 6.75, p < .001, η2 = 0.081]. None of the other effects were significant. An examination of the change effect sizes in Table 3 indicates that the BOOST condition clients reported a moderate to large improvement in family relations from baseline to the 5th (d = −.46) and the 12th month (d = −.50). The SAU clients reported changes reflecting a very small effect (d = −.10) from baseline to the 5th month and a moderate effect (d = −.34) from baseline to the 12th month.

The significant Condition x Gender interaction among the higher externalizing clients in family relations may be due to the poor responsiveness of females in the SAU condition. For example, their change from baseline to the 12th month [d = (4.17 – 4.20)/2.18 = −0.08] represented minimal improvement. However, females in the BOOST condition demonstrated a moderate-large effect size change from baseline to the 12th month [d = (5.93 – 6.92)/2.18 = −0.56]. Males in the SAU [d = (5.07 – 6.37)/2.18 = −0.59] and the BOOST [d = (5.21 −6.10)/2.18 = −0.41] condition both demonstrated moderate-large effects from baseline to the 12th month.

Adolescent Self-Reported Felony and Non-Felony Offenses

To examine the effects of supervision condition on youth offenses, we conducted a binary logistic regression with the 12-month indices as dependent variables and the baseline dichotomous index and Condition code as independent variables (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Percent and effect sizes reporting any Felony or Non Felony offenses by Condition and Assessments.

| Crime Status × Condition |

Assessment Point | Effect Sizes dϕ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5th month | 12th month | t0 -> t5 | to -> t12 | |

| SAU Felony | 20.7% | 16.7% | 8.7% | 0.10 | 0.35 |

| BOOST Felony | 21.7% | 13.3% | 4.8% | 0.22 | 0.53 |

| Total Felony | 21.5% | 14.6% | 5.9% | 0.18 | 0.474 |

| SAU Non-Felony | 44.8% | 22.2% | 30.4% | 0.485 | 0.298 |

| BOOST Non-Felony | 50.0% | 36.7% | 29.0% | 0.270 | 0.433 |

| Total Non-Felony | 48.1% | 31.3% | 29.4% | 0.347 | 0.387 |

Note: Cell entries are the percent of clients reporting any Felony or Non-Felony offenses during the 3-month period preceding the assessment date. Effect size comparisons from baseline to 5 months (t0 -> t5) or 12-month assessments (to -> t12) were based upon Cohen’s arcsin criteria. The baseline sample sizes were SAU= 59 and BOOST = 105.

The results of the regression analysis for the change from baseline were statistically significant both for the felony [B = −3.72, S.E. = 1.17, Wald(1) = 10.13, p < .001, Exp(B) = .024] and the non-felony offenses [B = −1.43, S.E. = 0.54, Wald(1) = 7.11, p < .008, Exp(B)= 0.24]. The Condition effect was not statistically significant [Wald < 0.55, p > .46] for either index. The data are based upon complete observations at each assessment (and do not include imputed scores). The effect sizes for the reduction in felony (dϕ = 0.474) and non-felony (dϕ = 0.387) offending from baseline to the 12th month assessment in the BOOST condition can be considered a medium or moderate effect size. A small effect from baseline to the 12th month assessment was also observed for felony (dϕ = 0.346) and non-felony (dϕ = 0.298) offenses in SAU.

Exploratory Analysis: Adolescent Internalizing Behaviors

To examine the impact of supervision condition on youth internalizing behavior problems, we categorized internalizing symptoms as being above or below clinically significant thresholds at all assessment points for both adolescent (YSR) and parent (CBCL) reports (see Table 5) and examined change in these indices from baseline to the 5th and the 12th month assessment points. It should be noted that we used percentage above clinical threshold as the primary dependent variable to maintain consistency with how internalizing was identified in the baseline analysis. As a sample of youth referred for behavior problems, this threshold represented a point at which youth might be referred for treatment.

Table 5.

Effects of Supervision Condition and time on the parent (CBCL) and adolescent (YSR) self-reported, clinically elevated internalizing symptoms.

| Internalizing Measure × Condition |

Assessment Point | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 months | 12 months | dϕ (t0-t5) | dϕ (t0-t12) | |

| CBCL BOOST | 54% | 29% | 28% | 0.506 | 0.532 |

| CBCL SAU | 58% | 33% | 29% | 0.502 | 0.593 |

| YSR BOOST | 29% | 24% | 20% | 0.126 | 0.215 |

| YSR SAU | 38% | 33% | 25% | 0.093 | 0.277 |

Note: Cell entries are the percent of parent (CBCL) and adolescent (YSR) clients reporting internalizing scores above clinical thresholds for the 3-month period preceding the assessment date. Effect size comparisons from baseline to 5 months (t0 -> t5) or 12 month assessments (to -> t12) are based upon Cohen’s arcsin criteria.

The change from baseline to the 5th and 12th months represented a large effect size for the parent CBCL ratings in the BOOST [dϕ (t0-t5) = 0.506; dϕ (t0-t12) = 0.532] and the SAU [dϕ (t0-t5) = 0.502; dϕ (t0-t12) = 0.593) conditions. However, the change in clinically elevated scores for the adolescent (YSR) internalizing scale represented a small effect size for the BOOST [dϕ (t0-t5) = 0.126; dϕ (t0-t12) = 0.215] and the SAU = [dϕ (t0-t5) = 0.093; dϕ (t0-t12) = 0.277] conditions).

Discussion

Similar to the community-based studies reviewed by Robbins et al. (2016), the results supported the positive impact of FFT in community settings, with both conditions showing significant improvements over time on the majority of variables. For example, both BOOST and SAU appeared to be consistently effective in improving, externalizing behaviors, youth offending, and internalizing behaviors. However, in this community-based sample of experienced FFT therapists, the findings provide modest support for the hypothesis that observation-based supervision methods could enhance youth and family outcomes. Specifically, intensifying supervision might help to bridge the gap in outcomes that have been observed between controlled efficacy trials and community-based implementation (e.g., Fixsen et al., 2005, Henggeler et al., 1999).

Although it is not clear if the current results were due to including observation-based methods in the supervision process or to the differential expertise of the supervisors, the results suggest that clinical outcomes can be enhanced by adding observation to the supervision process. However, to identify improvements in youth externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, it was necessary to adopt an analytic strategy that accounted for variation in clinical presentations (or “case mix”) at the point of referral. In contrast to controlled efficacy trials that limit heterogeneity, the focus of community-based effectiveness trials is to augment external validity by including a range of participants. This creates challenges for analyses because participants enter treatment for different reasons, and – as such – there is substantially more variability in the range of key dependent variables. In this study, we identified the most common presenting problem (youth externalizing behaviors) and examined the differential impact of supervision strategies on this variable for youth that presented above or below the clinical threshold for this problem.

Observation-based supervision conducted by very experienced supervisors enhanced clinical outcomes, but only for the above-clinical threshold group. Review of effect sizes by condition showed that BOOST was associated with larger effect sizes for both parent and youth reports of externalizing behaviors and criminal (felony and non-felony) offenses. With respect to gender, the positive effects of BOOST on externalizing were consistently observed across both male and female adolescents. There was more variation in externalizing outcomes in SAU, with female adolescents reporting positive outcomes in externalizing behaviors and males reporting only minimal change. In contrast, parents in SAU reported large improvements for males in SAU, and virtually no change for females. Prior research has yielded inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between gender and outcomes in FFT (Baglivio et al., 2013; Celinska & Cheng, 2017). Additional research with larger samples is necessary to examine if there are differential effects on outcomes by youth gender.

The findings demonstrated the positive impact of FFT on family functioning. Parents and youth in both conditions reported improvements in family functioning, and there was some evidence to suggest that observation-based methods implemented by highly experienced supervisors might enhance the effects of FFT on family functioning. Again, this pattern was only observed for the families with youth above the clinical threshold for externalizing behavior. Future research examining mediation, moderation, and mechanism of action must systematically account for variation in case mix to provide a more complex understanding of the change process, particularly among community-based samples that typically show much more variation in initial presentation.

Clinical Implications

One possible explanation for the current pattern of findings is that supervision in BOOST may have been more specific and individualized than supervision in SAU. That is, the observations of recordings made it possible to develop and provide recommendations that were tailored to interactions that were occurring in the session, both between family members as well as with the therapist. This more detailed feedback may have led to a long-term protective effect on sustaining the gains made during treatment over time. In contrast, therapists in SAU might have been provided with more general feedback and recommendations. Both therapists may have been successful in implementing the recommendations, but the more detailed approach in BOOST may have enhanced the effects by providing therapists with more specific and tailored feedback based on their actual in-session statements.

From this perspective, the results suggest that supervision is not a “one size fits all” process. That is, the more intensive supervision strategies might be reserved for the more difficult cases. Supervisors should attend to baseline information to identify cases that might benefit most from an intensified supervision process and devote resources to develop/tailor plans to meet higher risk cases. From a resource allocation perspective, supervisors can use baseline information to drive their planning and implementation process. Less risky cases appear to benefit as much by the standard supervision process (guided discussing using a web-based system) as they do from the more intensive BOOST procedure. As such, it does not make sense to implement a more intensive procedure for these cases. In contrast, higher risk cases might benefit more from a more intensive process. Given the realities of limited time available for support/supervision in real world settings, these results provide guidance about how limited resources might be allocated to achieve maximum effects.

It should be noted, however, that the modest impact of such a labor-intensive supervision method has an alternative explanation. That is, the simpler, cost-effective supervision structure used by FFT LLC is adequate to ensure treatment gains across the spectrum of referred youth and families and the labor-intensive, higher cost procedures may not add a lot with respect to outcomes. Future research economic analyses are needed to determine if the more intensive and costly procedures yield outcomes that are worth the extra effort involved in delivering these supervision strategies.

Limitations and Challenges

There are several potential limitations to the design of the current study. First, the sites (and therapist teams) included are not representative of the universe of agencies providing services to youth and families. All of the sites were part of the CIBHS system with extensive experience conducting FFT. Second, supervisors in the two conditions had different levels of family therapy experience. BOOST was implemented by highly trained and experienced clinical supervisors with more than a decade of experience supervising therapists in FFT and other EBTs. SAU was implemented by on-site clinical supervisors with approximately 2 to 3 years of experience with FFT. Thus, although the design ensured BOOST was carried out with high quality, it is not possible to determine if it was the utilization of observation-based methods or if it was different levels of supervisor experience that accounted for any changes observed between the supervision conditions. Third, the study did not include a detailed analysis of costs, cost savings, or cost-benefits. Thus, it is not clear if the outcomes of this study off-set the costs associated with the additional efforts required to implement the BOOST supervision protocol. Fourth, the number of participating Therapist Teams is small (n = 12), which made it challenging to detect potential site differences is limited. Fifth, the study design focused on identifying the differential effectiveness of supervision conditions on adolescent and family outcomes. Although the results of this study are contextualized within a broader conceptual framework (Fixsen et al., 2005) that includes organizational variables, training, and other factors that are critical for successful dissemination, within the constraints of the current research it is not possible to examine the effects of these variables on outcomes. Finally, the assessment completion rates observed in this project were markedly lower than rates we have observed in our prior efficacy and effectiveness studies. In part, this was due to the fact that RAs were spread over a large geographical area, which made it difficult to supervise/oversee their activities. RAs were also part time, contract employees and there was considerable variability in their involvement over time.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDA Grant R01 DA029406 to Holly Waldron and Michael Robbins, Co-Principal Investigators.

Footnotes

The authors are indebted to CIBMHS, Aleah Montano, Lisa Weaver, Pam Hawkins and the therapists who provided services, recorded sessions, and participated in the supervision process.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, & Parsons BV (1982). Functional family therapy: principles and procedures. Carmel, CA: Brooks & Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, Waldron HB, Robbins MS, & Neeb AA (2013). Functional Family Therapy for Adolescent Behavior Problems. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Jackowski K, Greenwald MA, & Wolff KT (2014). Comparison of multisystemic therapy and functional family therapy effectiveness: A multiyear statewide propensity score matching analysis of juvenile offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(9), 1033–1056. doi: 10.1177/0093854814543272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton C, Alexander JF, Waldron H, Turner CW, & Warburton J (1985). Generalizing Treatment Effects of Functional Family Therapy: Three Replications. American Journal of Family Therapy, 13, 16–26. doi: 10.1080/01926188508251260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin AE, & Garfield SL (Eds.). (1994). Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (4th ed.). Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram RM, Blasé KA, & Fixsen DL (2015). Improving programs and outcomes: Implementation frameworks and organization change. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 477–487. doi: 10.1177/1049731514537687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L (2008). A measurement feedback system (MFS) is necessary to improve mental health outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(10), 1114–1119. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825.af8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celinska K, & Cheng C (2017). Gender differences in the processes and outcomes of Functional Family Therapy. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 6(1), 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- Celinska K, Furrer S, & Cheng C (2013). An Outcome-based Evaluation of Functional Family Therapy for Youth with Behavioral Problems. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 2(2). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Chittams J, Barber JP, Beck AT, Frank A, . . . Woody G (1998). Training in cognitive, supportive-expressive, and drug counseling therapies for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66(3), 484–492. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blasé KA, Friedman RM, & Wallace F (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature [FMHI Publication No. 231]. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, & DeGarmo DS (2005). Evaluating Fidelity: Predictive Validity for a Measure of Competent Adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 3–13. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80049-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, & Marcus AC (2003). Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2012). Missing Data: Analysis and Design. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K, Johansson, Drott-Englén G, & Benderix Y (2004). Functional family therapy in child psychiatric practice. Nordisk Psykologi, 56(4), 304–320. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, & Brondino MJ (1999). Multisystemic treatment of substance abusing and dependent delinquents: Outcomes, treatment fidelity and transportability. Mental Health Service Research, 1, 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Liao JG, Letourneau EJ, & Edwards DL (2002). Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: The link between supervisory practices and therapist fidelity in MST programs. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(2), 155–167. doi: 10.1207/153744202753604449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base; and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63, 146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA (1991). Training and supervision in family therapy: A comprehensive and critical analysis In Gurman AS & Kniskern DP (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy, Vol. 2, pp. 638–697). Philadelphia, PA, US: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, & Greenbaum PE (2008). Treating adolescent drug abuse: A randomized trial comparing Multidimensional Family Therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Addiction, 103(10), 1660–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, . . . Argeriou M (1992). The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9(3), 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SF, & Irwin K (2003). Blueprints for Violence Prevention: From Research to Real-World Settings--Factors Influencing the Successful Replication of Model Programs. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 1(4), 307–329. doi: 10.1177/1541204003255841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, & Pirritano M (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, & Moos BS (1986). Family Environment Scale manual. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Alexander JF, Turner CW, & Hollimon A (2016). Evolution of Functional Family Therapy as an Evidence-Based Practice for Adolescents with Disruptive Behavior Problems. Family Process, 55(3), 543–557. doi: 10.1111/famp.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban D, Coatsworth JD, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Schwartz SJ, LaPerriere A, & Szapocznik J (2003). The efficacy of Brief Strategic Family Thearpy in modifying Hispanic adolescent behavior problems and substance use. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, & Chapman JE (2009). Clinical supervision in treatment transport: Effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm CL, McDowell T, & Long JK (2013). The metamorphosis of training and supervision In Sexton TL, Weeks GR, & Robbins MS (Eds), Handbook of Family Therapy, Volume 2, pp. 431–448. New York: Brunner-Routledge, [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Konenberg GR, Han SS, & Kauneckis D (1995). Child and adolescent psychotherapy outcomes in experiments versus clinics: Why the disparity? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(1), 83–106. doi: 10.1007/BF01447046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey-Stirman S, Gutner CA, Crits-Christoph P, Edmunds J, Arthur C Evans AC, & Beidas RS (2015) Relationships between clinician-level attributes and fidelity-consistent and fidelity-inconsistent modifications to an evidence-based psychotherapy. Implementation Science (2015) 10:115 DOI 10.1186/s13012-015-0308-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]