Abstract

Background

Women are at greater risk of developing pulmonary arterial hypertension, with estrogen and its downstream metabolites playing a potential role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1‐α (HIF1α) is a pro‐proliferative mediator and may be involved in the development of human pulmonary arterial hypertension. The estrogen metabolite 2‐methoxyestradiol (2ME2) has antiproliferative properties and is also an inhibitor of HIF1α. Here, we examine sex differences in HIF1α signaling in the rat and human pulmonary circulation and determine if 2ME2 can inhibit HIF1α in vivo and in vitro.

Methods and Results

HIF1α signaling was assessed in male and female distal human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs), and the effects of 2ME2 were also studied in female hPASMCs. The in vivo effects of 2ME2 in the chronic hypoxic rat (male and female) model of pulmonary hypertension were also determined. Basal HIF1α protein expression was higher in female hPASMCs compared with male. Both factor‐inhibiting HIF and prolyl hydroxylase‐2 (hydroxylates HIF leading to proteosomal degradation) protein levels were significantly lower in female hPASMCs when compared with males. In vivo, 2ME2 ablated hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension in male and female rats while decreasing protein expression of HIF1α. 2ME2 reduced proliferation in hPASMCs and reduced basal protein expression of HIF1α. Furthermore, 2ME2 caused apoptosis and significant disruption to the microtubule network.

Conclusions

Higher basal HIF1α in female hPASMCs may increase susceptibility to developing pulmonary arterial hypertension. These data also demonstrate that the antiproliferative and therapeutic effects of 2ME2 in pulmonary hypertension may involve inhibition of HIF1α and/or microtubular disruption in PASMCs.

Keywords: 2‐methoxyestradiol, HIF1α, pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular changes, sex hormones, smooth muscle cell

Subject Categories: Vascular Disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

We have shown that hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1‐α (HIF1α) protein expression is increased in female pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) compared with male PASMCs and that the regulatory mechanisms that govern HIF1α expression and activity are lower in female PASMCs.

This study has also shown that 2‐methoxyestradiol is an effective inhibitor of HIF1α, both in vivo and in vitro.

We have also demonstrated that 2‐methoxyestradiol can affect PASMC microtubule structure, which may further contribute to its antiproliferative properties.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Increased HIF1α expression and activity is associated with many hyperproliferative disease states, including pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Women are at greater risk of developing pulmonary arterial hypertension; therefore, increased basal expression of HIF1α may predispose female PASMCs to a state of increased proliferative capacity and contribute to pulmonary artery wall remodeling.

Furthermore, inhibition of HIF1α and disruption of microtubule structure with 2‐methoxyestradiol may be an effective treatment to reduce or prevent pulmonary artery remodeling.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease characterized by pulmonary arterial tone dysfunction and hyperproliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). Women have a greater risk of developing PAH, with registries reporting the female‐to‐male ratio as high as 4:1.1, 2 The role of estrogen (E2) and estrogen metabolism in the development of PAH has been studied extensively. Indeed, estrogen and its downstream metabolite 16α–hydroxyestrone have been demonstrated to be involved in pro‐proliferative responses in PASMCs and may be involved in the development of the human disease.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Studies have also suggested a potential protective role for estrogen metabolites such as 2‐hydroxyestradiol, 4‐hydroxyestradiol, and 2‐methoxyestradiol (2ME2). These can inhibit smooth muscle cellular proliferation and/or reverse experimental pulmonary hypertension (PH).5, 9, 10 2ME2 is perhaps the best studied of these metabolites and has been shown to reverse PH in the bleomycin and monocrotaline rat models.9, 11, 12 However, the mechanism as to how 2ME2 mediates this protective effect in the pulmonary system is unknown. 2ME2 has also been postulated to be beneficial in other hyperproliferative disease states such as cancer. Here, 2ME2 may arrest abnormal cellular growth and migration by disruption of the cytoskeletal network through depolymerization and disorganization of α‐tubulin.13, 14 This, in turn, has been shown to have a detrimental effect on hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1‐α (HIF1α) stability and function.13 HIF1α is a crucial mediator of many cellular functions. Under normoxic conditions, HIF1α is hydroxylated through the prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs). Hydroxylated HIF1α is then recognized by the Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein, which tags the hydroxylated HIF1α for proteosomal degradation through the E3 ubiquitin‐ligase system.15 However, under conditions of reduced‐oxygen tension, the PHDs become inhibited and HIF1α stabilizes within the cell where it can then translocate to the nucleus and interact with its binding partners HIF1β and the hypoxic response element to regulate transcription of many genes.15, 16 HIF1α is further regulated by the asparaginal hydroxylase factor inhibiting HIF (FIH), which hydroxylates HIF1α and blocks association of HIF1α with its transcriptional coactivators.17 HIF1α has also been implicated in the development of PAH, with increased protein expression observed in distal pulmonary arteries of idiopathic PAH patients.18 Furthermore, increased activity of HIF1α is associated with an increase in mitogenic and angiogenic genes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2) and vascular endothelial cell growth factor A.18, 19, 20 To date, there have been limited studies assessing sex differences in HIF1α signaling in the pulmonary circulation. Our hypothesis was that there are sex differences in HIF1α signaling in human PASMCs (hPASMCs) and that HIF1α signaling plays a role in the in vivo effects of 2ME2 in the rat hypoxic model of pulmonary hypertension. We also assessed the molecular mechanisms behind the effects of 2ME2 in both human and rat PASMCs.

Methods

Data within this paper can be found on the University of Glasgow approved data repository (http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/datamanagement/lookingafteryourdata/preservation/repositories).

An expanded methods section is available in Data S1.

Animal Studies

All experimental procedures conform to the UK Animal Procedures Act (1986) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health No. 85‐23, revised in 1996, as well as local institutional guidelines. We chose to study the hypoxic rat model instead of the sugen/hypoxic rat, as we have previously shown that sugen decreases HIF1α expression in hPASMCs.21 Briefly, male and female Sprague Dawley rats were placed in hypobaric conditions (550 mbar) for 2 weeks. Rats were then removed and dosed with a subcutaneous slow‐release pellet containing either 2ME2 (1.26 mg pellet/21 days; 60 μg/kg per day) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK/Innovative Research of America; Sarasota, FL) or vehicle carrier (Innovative Research of America) for a further 2 weeks in hypoxic conditions. Normoxic animals were weight matched and dosed in an identical fashion. We chose to administer 2ME2 by slow‐release pellet in an attempt to overcome the low bioavailability and short plasma half‐life of 2ME2.22

Hemodynamic Measurements

Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) measurements and associated parameters were recorded using a Miller SPR‐869 catheter and analyzed using the corresponding software (LabChart Pro version 8, ADInstruments; Dunedin, New Zealand) as described previously and in Data S1.3

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

To assess right ventricular hypertrophy, the right ventricular free wall was removed and weighed. This was then expressed as a ratio to the left ventricular wall plus septum weight.

Culture and Isolation of PASMCs

Unless otherwise stated, female and male hPASMCs were isolated from pulmonary arteries of non‐PAH patients undergoing a pneumonectomy procedure (0.3–1 mm diameter) from distal portions of macroscopically normal lung tissue as described previously (http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/datamanagement/lookingafteryourdata/preservation/repositories) and in Table S1. All studies on human tissue were approved by an institutional review committee, and studies conformed to local and national guidelines. Specific details on isolation of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) can also be found in Data S1.

Cellular Proliferation Experiments

Cellular proliferation was assessed manually using a hemocytometer or using the cell counting kit 8 (CCK8) assay (Dojindo; Kumamoto, Japan). See Data S1 for more details.

Caspase Activity

Caspase‐3/7 activity was measured using the Cell Event assay (ThermoFisher; Runcorn, UK) and used according to manufacturer's instructions. See Data S1 for more details.

Immunoblotting

Protein expression was assessed by immunoblotting in whole lung tissue and hPASMCs. Details of antibodies used are shown in Table S2.

Florescent Imaging

Cellular localiztion of α‐tubulin in hPASMCs and rat PASMCs was assessed by immunofluorescence. See Data S1 for more details.

TaqMan Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

mRNA transcripts from hPASMCs and rat whole lung tissue were assessed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Specific dual‐labeled TaqMan primer‐probe sets were purchased from ThermoFisher (Table S3).

Histopathology

Saggital sections of lung (5 μm) were stained with elastin–picrosirius red. The number of remodeled vessels (as indicated by a double elastic lamina) per section were assessed in a blinded fashion. More details can be found in Data S1.

Statistical Analysis

All graphs and statistical analyses were produced and performed using Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc; La Jolla, CA). All data are shown as mean±SEM and a P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ratio data were log‐transformed to ensure that they were normally distributed before employing parametric statistical analysis. For the comparison between vehicle and drug‐treated cells, a paired t‐test was employed, as cells from each patient were separated into 2 and cultured, so that cells from the same patient line were tested in the presence of vehicle and 2ME2. For comparison of 2 independent groups, a 2‐tailed Student's unpaired t‐test was used. For comparison of >2 groups, a 1‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test was used. Statistical analysis used for each data set is indicated in the figure legend of each figure. Data are also displayed as fold change for interpretation purposes.

Results

Sex Differences in HIF1α Signaling

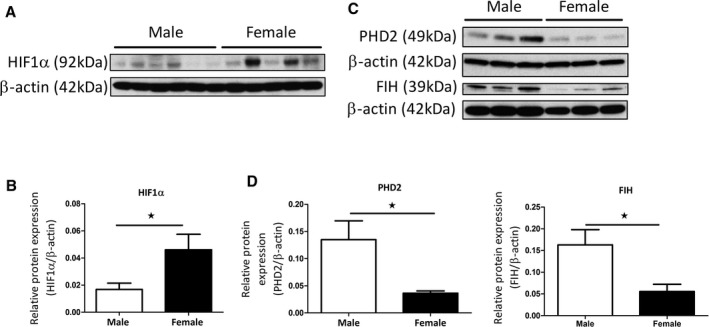

Basal protein expression of HIF1α was variable but significantly higher in female hPASMCs compared with males (Figure 1A and 1B). There was increased basal PHD2 and FIH protein levels in male hPASMCs compared with female hPASMCs (Figure 1C and D). mRNA transcript analysis revealed that there were no differences in HIF1α, PHD1, PHD2, PHD3, or Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor levels between male and female hPASMCs (Figure S1A through S1E). FIH mRNA levels were significantly lower in female hPASMCs (Figure S1F). Treatment with E2 (100 nmol/L; 72 hours) caused a significant decrease in FIH mRNA levels in both male and female hPASMCs compared with vehicle controls (Figure S1G and S1H).

Figure 1.

HIF1α signaling in male and female hPASMCs. Representative western blot of HIF1α protein expression in male and female hPASMCs (A) and densitometric analysis (B). Representative western blots of PHD2 and FIH protein expression in male and female PASMCs (C) with densitometric analysis (D). Data are shown as mean±SEM. n=3 to 6; *P<0.05 as determined by a Student's unpaired t‐test. Membranes were cut at an appropriate point and probed for separate antibodies. Membranes were then stripped and re‐probed with β‐actin. FIH indicates factor‐inhibiting hypoxia‐inducible factor; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; PHD2, prolyl hydroxylase‐2.

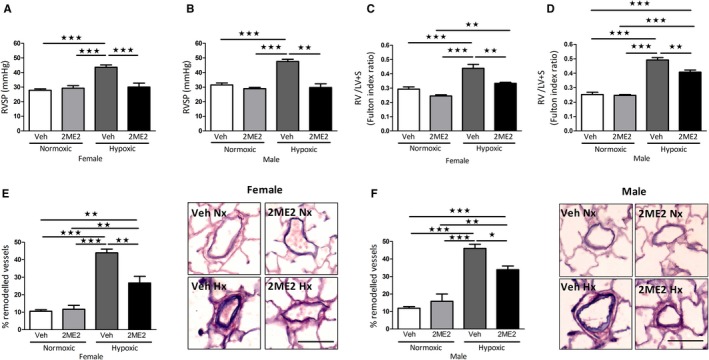

Effect of 2ME2 on Hemodynamic Measurements in the Chronic Hypoxic Model of PH

Chronic hypoxia caused a significant increase in RVSP, right ventricular hypertrophy, and pulmonary artery remodeling in both female and male rats (Figure 2). 2ME2 reduced RVSP in female and male rats (Figure 2A and 2B), right ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 2C and 2D) and in the percentage of remodeled vessels observed (Figure 2E and 2F).

Figure 2.

Effect of 2ME2 on development of pulmonary hypertension in the chronic‐hypoxic rat model. Effects of 2ME2 on RVSP in female (A) and male rats (B). Effects of 2ME2 on right ventricular hypertrophy in female (C) and male rats (D) and pulmonary artery remodeling with representative photomicrographs of lung sections stained with elastin‐picrosirius red in female (E) and male rats (F). Data are shown as mean±SEM. All groups n=5; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 determined by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Scale bar indicates 70 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; Hx, hypoxic; Nx, normoxic; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; Veh, vehicle.

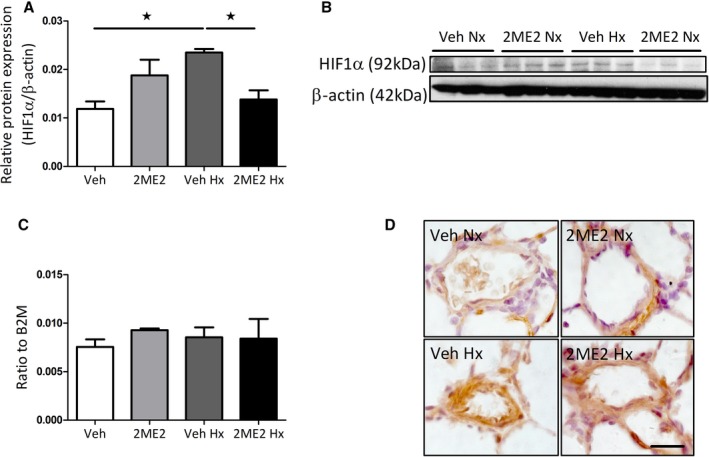

In Vivo Effects of 2ME2 on HIF1α Expression in the Chronic Hypoxic Model

Chronic hypoxia caused an increase in HIF1α protein expression in female rat whole lung tissue, which was subsequently reduced by 2ME2 (Figure 3A and 3B). No changes in HIF1α mRNA levels were observed in whole lung tissue (Figure 3C). 2ME2 also reduced regional expression of HIF1α in the smooth muscle of distal pulmonary arteries in normoxia and hypoxia (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Effects of 2ME2 on HIF1α expression in female hypoxic rat lung. Effects of 2ME2 on whole lung protein expression of HIF1α (A) with representative immunoblot (B) and whole lung HIF1α mRNA transcript expression (C) (n=4). Representative micrographs of HIF1α expression in distal pulmonary arteries in normoxic vehicle, normoxic 2ME2 treated, hypoxic vehicle and hypoxic 2ME2 treated rats (D). Data are shown as mean±SEM. *P<0.05 determined by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; HIF1α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1‐α; Hx, hypoxic; Nx, normoxic; Veh, vehicle. Scale bar indicates 20 μm.

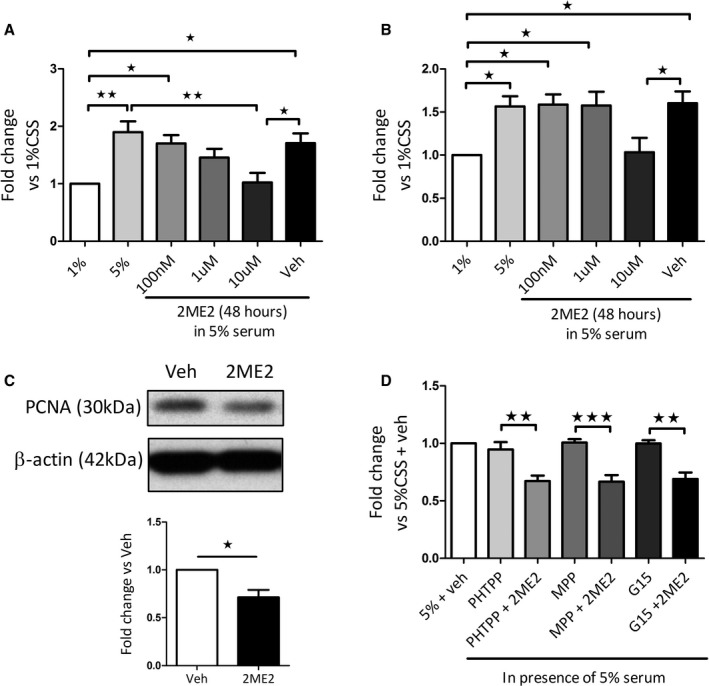

Effects of 2ME2 on Cellular Proliferation in PASMCs

We investigated the role of 2ME2 (100 nmol/L–10 μmol/L) in the proliferative response of female hPASMCs. 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) caused a significant decrease in cellular number in hPASMCs compared with vehicle control (Figure 4A [cell counts] and B [CCK8 assay]). A significant reduction in proliferating cell nuclear antigen protein (PCNA) levels after 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) was also observed in female hPASMCs (Figure 4C). This reduction in proliferation by 2ME2 in hPASMCs was not abrogated by the estrogen receptor (ER)α antagonist MPP, the ERβ antagonist PHTPP or the G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1 antagonist G15 (all 100 nmol/L) (Figure 4D). 2ME2 also caused a significant reduction in the proliferative responses in isolated rat PASMCs after 48 hours (Figure S2).

Figure 4.

Effect of 2ME2 on the cellular proliferation of female hPASMCs. Effect of 2ME2 (100 nm–10 μmol/L) on fetal bovine serum–induced proliferation in female hPASMCs assessed by manual cell counts (A), cell counting kit 8 assay (B) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen protein expression after 48 hours (C) (n=4–5). Effect of preincubation with of the ERα antagonist MPP (100 nmol/L), ERβ antagonist PHTPP (100 nmol/L) and G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1 antagonist G15 (100 nmol/L)±2ME2 (10 μmol/L) in non‐PAH female hPASMCs (D) (n=4). Data are shown as mean±SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 as indicated. Statistical analysis: (A through D) determined by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test; panel C determined by paired t‐test. 1%, 1% serum; 5%, 5% serum. Membranes were cut at an appropriate point and probed for separate antibodies. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with β‐actin. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; ERα, estrogen receptor‐alpha; ERβ, estrogen receptor‐beta; hPASMCs, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

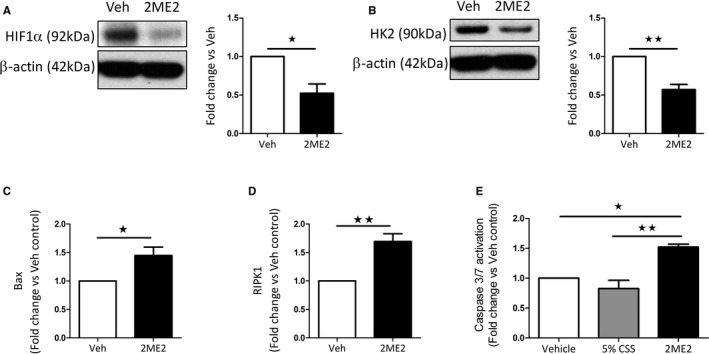

Effect of 2ME2 on HIF1α Protein Expression in hPASMCs

2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) caused a significant reduction in HIF1α protein levels and downstream HK2 expression in hPASMCs (Figure 5A and 5B, respectively).

Figure 5.

Effects of 2ME2 on female hPASMCs. HIF1α (A) and hexokinase 2 (HK2) (B) protein expression in 2ME2 (10 μmol/L; 48 hours) treated female hPASMCs. Bax (C) and RIPK1 (D) mRNA transcript expression in 2ME2 (10 μmol/L; 48 hours) treated female hPASMCs. (n=4–5). CellEvent Caspase 3⁄7 Green activity in female hPASMCs after 6‐hour stimulation with 2ME2 (E) (10 μmol/L; n=3). Data are shown as mean±SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; as indicated. Statistical analysis: (A through D) determined by paired t test; Panel E determined by 1‐way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's test. Membranes were cut at an appropriate point and probed for separate antibodies. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with β‐actin. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; Bax, Bcl‐associated X; CSS, charcoal‐stripped serum; HIF1α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1‐α; hPASMCs, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; RIPK1, receptor‐interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 1; Veh, vehicle.

Effects of 2ME2 on Expression of Proapoptotic and Antiproliferative Mediators

A significant increase in the proapoptotic Bcl‐associated X mRNA transcript was observed in hPASMCs after treatment with 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) (Figure 5C). 2ME2 also caused an increase in the necroptotic mediator receptor‐interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) in hPASMCs (Figure 5D). Furthermore, 2ME2 increased activated caspase 3/7 (Figure 5E). 2ME2 had no effect on caspase 9 or p53 mRNA transcript levels in hPASMCs or on bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II expression levels (Figure S3).

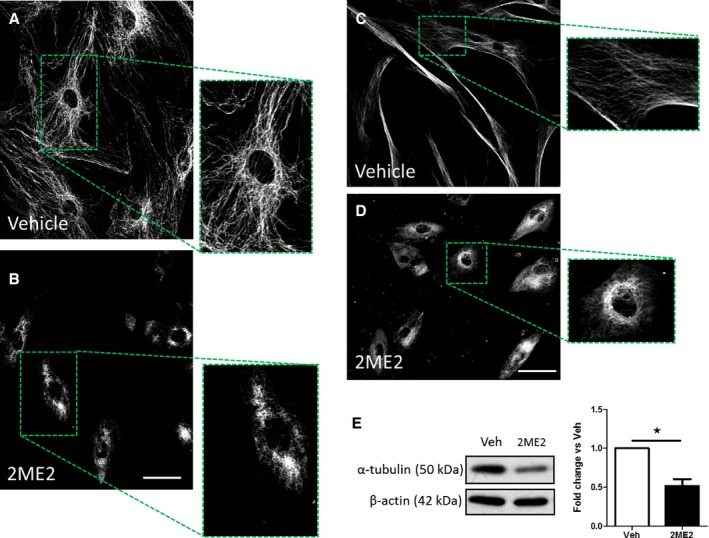

Effects of Microtubule Disrupters and 2ME2 on Cellular Morphology and Cytoskeletal Network in PASMCs

2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) caused significant changes in cellular morphology in hPASMCs with a decrease in cellular perimeter observed (Figure S4). 2ME2 also caused disruption of the cytoskeletal α‐tubulin network in both hPASMCs and rat PASMCs (Figure 6A through D) and resulted in a significant reduction in α‐tubulin protein levels in female hPASMCs (Figure 6E). 2ME2's effects on cellular morphology and tubulin structure were compared with Taxol and colchicine. Colchicine caused similar morphological changes in cellular structure (Figure S5). However, colchicine appeared to be more potent than 2ME2 in disrupting the microtubule structure in female hPASMCs (Figure S6).

Figure 6.

Assessment of α‐tubulin organization and expression after treatment with 2ME2. α‐tubulin cellular localization in female rat PASMCs (A) and after 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 24 hours) (B); α‐tubulin cellular localization in female hPASMCs (C) and after 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 24 hours) (D). Effect of 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 24 hours) on protein expression levels of α‐tubulin protein expression in female hPASMCs (E). Data are shown as mean±SEM. *P<0.05. Statistical analysis: Panel E determined by paired t‐test. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMCs, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

Here, for the first time, we have demonstrated differences in HIF1α signaling between male and female hPASMCs. We have also demonstrated the ability of 2ME2 to reverse hypoxia‐induced PH in men and women and identified mechanisms by which 2ME2 may be protective in experimental PH. In the chronic hypoxic rat, we confirmed that 2ME2 caused a significant reduction in pulmonary artery remodeling, associated RVSP and right ventricular hypertrophy in both male and female rats. The most profound effect of 2ME2 was on the increased RVSP in hypoxia, which was completely reversed. This is not attributable to 2ME2‐induced vasodilation, as it has been shown previously that 2ME2 is not vasoreactive in this regard. These data are consistent with the effects of 2ME2 in monocrotaline‐ and bleomycin‐induced PH models.9, 11, 12 2ME2 has been reported to be an HIF1α inhibitor,23 so we examined the role of HIF1α in the in vivo effects of 2ME2. Following 2ME2 administration in vivo, we observed a significant reduction in HIF1α protein levels in the whole lung, suggesting that 2ME2 can reduce HIF1α expression. Indeed, 2ME2 has been shown to cause a reduction in the HIF1α/oxidative stress pathway in the chronic hypoxic rat model.24 Similarly, we demonstrated that 2ME2 can inhibit HIF1α in hPASMCs.

We demonstrated that female hPASMCs have higher basal levels of HIF1α protein than male hPASMCs, which may be a result of increased PHD2 expression within these cells. In addition, ERβ can stabilize HIF1α in prostate cancer cell lines.25 Either of these mechanisms may lead to increased HIF1α in female hPASMCs. Notably, however, female hPASMCs have significantly lower levels of the oxygen‐dependent asparaginyl hydroxylase, FIH, a crucial inhibitor of the transactivational capacity of HIF1α.26 To determine whether estrogen had any influence on FIH, we treated both male and female hPASMCs with estrogen and demonstrated that FIH mRNA levels decreased significantly. We chose to study the effects of estrogen, as it is the predominant female hormone that is known to act via estrogen receptors, whereas 2ME2 has little to no affinity for any of the estrogen receptors. Decreased FIH levels in females may increase the capacity of HIF1α to activate target genes in these cells. Furthermore, estrogen is likely to play a role in this activity through an as of yet unidentified pathway. We have shown previously that female hPASMCs are more proliferative than male hPASMCs when treated with promitogenic compounds such as serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine).5 Overall, increased basal levels of HIF1α and/or reduced inhibition of HIF1α may render female hPASMCs more susceptible to “second‐hit” pro‐proliferative mediators such as serotonin. Importantly, most of the cells used within this study were of postmenopausal age, as it was not possible to obtain PASMCs from younger donors; therefore, age and menopausal status cannot be ruled out as a potential factor in determining HIF1α expression and activity.

As female hPASMCs have inherently higher levels of HIF1α and women are 4 times more likely to develop PAH, we chose to focus solely on female hPASMCs to determine what effect the molecular mechanisms of 2ME2 treatment may have on these cells. 2ME2 caused a significant reduction in proliferation in hPASMCs and female rat PASMCs. Indeed, this concentration range is consistent with previous findings in other cells types, and hPASMCs that have shown a significant reduction in cellular number after 2ME2 treatment.11, 27 This antiproliferative effect was observed in the presence of estrogen receptor antagonists and suggests that 2ME2 is not acting through classical estrogen receptors to have its antiproliferative effect in hPASMCs. This is consistent with previous reports that 2ME2 has little or no affinity for estrogen receptors but does bind to tubulin.28 Despite the fact that the receptors that mediate the biological effect of 2ME2 remain ill defined, it is reported to have numerous cardiovascular protective effects including inhibition of endothelin‐1, production of prostacyclin, nitric oxide production, and antioxidant effects.29 In addition, it has been proposed previously that 2ME2 may mediate some, but not all, of the antiproliferative effects of estrogen, effects that are independent of estrogen receptors.29 The antiproliferative effects of estrogen are known to be mediated by both estrogen receptor–dependent and independent mechanisms. Indeed, we have shown previously that proliferation of hPASMCs can be mediated by the ERα receptor associated with mitogen‐activated protein kinase and Akt signaling.30 2ME2 induced a significant decrease in basal levels of HIF1α protein in non‐PAH hPASMCs. A reduction in HIF1α levels may well lead to the less proliferative phenotype observed after treatment with 2ME2. Interestingly, 2ME2 caused a significant decrease in the downstream protein HK2 hPASMCs. HK2 is one of many well‐defined HIF1α target genes and a crucial component of the glycolytic pathway. Metabolic switching to a more glycolytic phenotype in both experimental PH and PAH has been stated previously18, 31, 32; therefore, assessing HK2 expression in our model was an important indicator of both the metabolic state and HIF1α activity within hPASMCs after 2ME2 treatment. Our data also suggest that 2ME2 may induce proapoptotic pathways as well as antiproliferative pathways in hPASMCs. 2ME2 induced an increase in the mitophagy‐related Bcl‐associated X mRNA and the necroptotic related RIPK1 mRNA where RIPK1 allows the cell to undergo cell death in the absence of caspase activity.33 Increases in Bcl‐associated X expression with 2ME2 has been detailed previously in an epithelial cancer cell line.34 Increased activity of caspase 3/7 provides further evidence for an apoptotic phenotype. These factors may well be central to the reduced cellular number observed in female hPASMCs in the presence of 2ME2. The apoptotic phenotype in PASMCs caused by 2ME2 may not be surprising on the basis of previous observations in other cell types.27, 35, 36 We also observed a disruption of microtubules in both human and rat PASMCs; microtubule disruption has long been postulated to be a potential treatment in hyperproliferative cells.37 There is also evidence that microtubule disruption causes apoptotic cell death as a result of dysfunctional protein trafficking,38, 39 which may play a role in the effects of 2ME2 in hPASMCs. Furthermore, microtubule disruption has been demonstrated to inhibit HIF1α in many cell types.13, 23, 40, 41 Previous experiments have shown that 2ME2 can inhibit microtubule polymerization through 2ME2 binding to tubulin at or near the colchicine‐binding site.42 This microtubule disruption may also contribute to the reduced perimeter and increased cellular size observed within the hPASMCs treated with 2ME2 as both α‐ and β‐tubulin monomers are important for regulating cellular shape, motility, and division.43 Interestingly, we also observed a reduction in α‐tubulin protein levels in hPASMCs in the presence of 2ME2. It is unknown whether this is a negative feedback response in reaction to altered α‐tubulin structure and dynamics. Previous studies in renal cells have noted a similar effect in response to the microtubule disruptors vincristine and dolastatin.44 This study also showed that hPASMC microtubules were stabilized with taxol and disrupted with colchicine. Interestingly, a recent study has also demonstrated that colchicine was effective in reversing experimental PH by improving right ventricular function and pulmonary hemodynamics.45 Taken together, this further suggests that microtubule disruption may be a potential therapeutic avenue in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

Conclusions

Estrogen is considered an important factor in female PAH patients, both before and after menopause, and men with PAH. Indeed, it has been shown recently that plasma estrogen levels are elevated in postmenopausal female PAH patients as well as men with idiopathic PAH.46, 47 In addition, the levels of estrogen were associated with disease severity.

Higher levels of HIF1α in female hPASMCs may make them more susceptible to promitogenic agents and subsequent pulmonary vascular remodeling. 2ME2 has multiple mechanisms of action that are cell and tissue specific. Here, we show that the antiproliferative effects of 2ME2 are not mediated through any of the estrogen receptors. In female hPASMCs, in vitro, 2ME2 lowers HIF1α protein expression and has both antiproliferative and proapoptotic properties. Furthermore, 2ME2 also causes significant microtubule dysruption which is likely to be the mechanism behind reduced HIF1α levels and the anti‐proliferative effect of 2ME2 in these cells. In vivo, 2ME2 reversed hypoxia‐induced PH and reduced lung HIF1α expression. These data suggest that disrupting microtubules and thereby inhibiting HIF1α may be a plausible translational target for PAH. Figure S7 summarizes our findings, suggesting a possible mechanism of action for 2ME2.

Sources of Funding

This article was funded by the British Heart Foundation grants PG/15/63/31659 and RG/16/2/32153.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1. Expanded Materials and Methods.

Table S1. Patient Details of Non‐PAH Male and Female hPASMCs Used Within This Study

Table S2. Antibodies and Dilutions Used for Western Blotting (WB) or Immunofluorescence (IF)

Table S3. Probe Sets Used Within This Study and Taqman Assay ID Details

Figure S1. HIF1α signaling in female hPASMCs. mRNA transcript expression levels of HIF1α (A) prolyl hydroxylase 1 (PHD1; B), prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2; C), prolyl hydroxylase 3 (PHD3, D), Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL; E) and factor‐inhibiting HIF (FIH, F). Effect of 72 hours treatment with 100 nmol/L E2 on FIH mRNA expression in male (G) and female (H) hPASMCs. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ★P<0.05; ★★P<0.01 determined by unpaired or paired t‐test. hPASMC indicates human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

Figure S2. Effect of 2ME2 on the cellular proliferation of rat PASMCs. Effect of 2ME2 (100 nm–10 μmol/L) on fetal bovine serum–induced proliferation in isolated rat female PASMCs assessed by manual cell counts (A) and CCK8 assay (B) after 48 hours (n=5 and 4, respectively). Data are shown as mean±SEM. ★P<0.05; ★★P<0.01; ★★★P<0.001 determined by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells;Veh, vehicle.

Figure S3. Effects of 2ME2 on proapoptotic genes in female hPASMCs. Effect of 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) on mRNA transcript expression levels of caspase 9 (A) and p53 (B) in female hPASMCs. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II mRNA (C) and protein expression (D) in female PASMCs. Data is shown as mean±SEM. Statistical analysis determined by paired t‐test. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMCs, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S4. Morphological changes in female hPASMCs associated with 48 hours 2ME2 treatment. Bright field images after 1% CSS (A), 5% CSS (B), 100 nmol/L 2ME2 (C), 1 μmol/L 2ME2 (D), 10 μmol/L 2ME2 (E) and vehicle (F). Cellular perimeter measurements in female hPASMCs in presence of 10 μmol/L 2ME2 (G) (n=3). Scale bar indicates 70 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; CSS, charcoal‐stripped serum; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

Figure S5. Comparison of morphological changes in female hPASMCs after stimulation with various microtubule mediators. Bright field images after 24 hours treatment with Taxol (10 μmol/L), colchicine (10 μmol/L), and 2ME2 (10 μmol/L) (n=3). Scale bar indicates 70 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S6. Effects of microtubule mediators on α‐tubulin organization in female hPASMCs. High‐resolution confocal microscopy images of α‐tubulin after treatment with Taxol (10 μmol/L), colchicine (10 μmol/L) and 2ME2 (10 μmol/L) (n=3) with increased digital magnification (inset). Arrows indicate condensing/disruption to the microtubule network. Scale bar indicates 10 and 5 μm (inset). 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S7. Schematic representation of 2ME2 mechanisms of action in female hPASMCs. 2ME2 causes α‐tubulin dysregulation, which in turn can cause reduced HIF1α and HK2 protein expression. Disruption of α‐tubulin may also lead to increases in apoptotic genes Bax and RIPK1 and activation of caspase 3/7. Green arrow, upregulation. Red arrow, down regulation. Blue arrow, causes/leads to. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; HK2, hexokinase 2; Bax, Bcl‐associated X; RIPK1, receptor‐interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Nicholas Morrell (Cambridge, UK) for supplying the human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, and Lynn Loughlin for her technical assistance. The authors also thank Glasgow Caledonian University for the use of the LSM‐800 confocal microscope, and Dr Patricia Martin for her assistance, as well as Dr John McClure (University of Glasgow) for his assistance with statistical analysis. Author contributions: involvement in the conception, hypotheses delineation, and design of the study: C.K.D., M.R.M; acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information: C.K.D., M.R.M., M.N; writing of the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission: C.K.D., M.R.M.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011628 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011628.)

References

- 1. Ling Y, Johnson MK, Kiely DG, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, Gibbs JS, Howard LS, Pepke‐Zaba J, Sheares KK, Corris PA, Fisher AJ, Lordan JL, Gaine S, Coghlan JG, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA, Peacock AJ. Changing demographics, epidemiology, and survival of incident pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the pulmonary hypertension registry of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farber HW, Miller DP, Poms AD, Badesch DB, Frost AE, Muros‐Le Rouzic E, Romero AJ, Benton WW, Elliott CG, McGoon MD, Benza RL. Five‐year outcomes of patients enrolled in the reveal registry. Chest. 2015;148:1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. White K, Johansen AK, Nilsen M, Ciuclan L, Wallace E, Paton L, Campbell A, Morecroft I, Loughlin L, McClure JD, Thomas M, Mair KM, MacLean MR. Activity of the estrogen‐metabolizing enzyme cytochrome p450 1b1 influences the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2012;126:1087–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hood KY, Montezano AC, Harvey AP, Nilsen M, MacLean MR, Touyz RM. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase‐mediated redox signaling and vascular remodeling by 16α‐hydroxyestrone in human pulmonary artery cells: implications in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mair KM, Yang XD, Long L, White K, Wallace E, Ewart MA, Docherty CK, Morrell NW, MacLean MR. Sex affects bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Austin ED, Lahm T, West J, Tofovic SP, Johansen AK, MacLean MR, Alzoubi A, Oka M. Gender, sex hormones and pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:294–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ventetuolo CE, Ouyang P, Bluemke DA, Tandri H, Barr RG, Bagiella E, Cappola AR, Bristow MR, Johnson C, Kronmal RA, Kizer JR, Lima JA, Kawut SM. Sex hormones are associated with right ventricular structure and function: the MESA‐right ventricle study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ventetuolo CE, Mitra N, Wan F, Manichaikul A, Barr RG, Johnson C, Bluemke DA, Lima JA, Tandri H, Ouyang P, Kawut SM. Oestradiol metabolism and androgen receptor genotypes are associated with right ventricular function. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tofovic SP, Salah EM, Mady HH, Jackson EK, Melhem MF. Estradiol metabolites attenuate monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tofovic SP, Zhang X, Zhu H, Jackson EK, Rafikova O, Petrusevska G. 2‐ethoxyestradiol is antimitogenic and attenuates monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;48:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tofovic SP, Zhang X, Jackson EK, Zhu H, Petrusevska G. 2‐methoxyestradiol attenuates bleomycin‐induced pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in estrogen‐deficient rats. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51:190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tofovic SP, Jones T, Petrusevska G. Dose‐dependent therapeutic effects of 2‐methoxyestradiol on monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodelling. Prilozi. 2010;31:279–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, LaVallee TM, Pribluda VS, Swartz GM, Johnson MS, Willard MT, Zhong H, Simons JW, Giannakakou P. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamath K, Okouneva T, Larson G, Panda D, Wilson L, Jordan MA. 2‐Methoxyestradiol suppresses microtubule dynamics and arrests mitosis without depolymerizing microtubules. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2225–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greer SN, Metcalf JL, Wang Y, Ohh M. The updated biology of hypoxia‐inducible factor. EMBO J. 2012;31:2448–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia‐inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:967–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang N, Fu Z, Linke S, Chicher J, Gorman JJ, Visk D, Haddad GG, Poellinger L, Peet DJ, Powell F, Johnson RS. The asparaginyl hydroxylase FIH (factor inhibiting HIF) is an essential regulator of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2010;11:364–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marsboom G, Toth PT, Ryan JJ, Hong Z, Wu X, Fang YH, Thenappan T, Piao L, Zhang HJ, Pogoriler J, Chen Y, Morrow E, Weir EK, Rehman J, Archer SL. Dynamin‐related protein 1‐mediated mitochondrial mitotic fission permits hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and offers a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;110:1484–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riddle SR, Ahmad A, Ahmad S, Deeb SS, Malkki M, Schneider BK, Allen CB, White CW. Hypoxia induces hexokinase II gene expression in human lung cell line A549. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L407–L416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veith C, Schermuly RT, Brandes RP, Weissmann N. Molecular mechanisms of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐induced pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell alterations in pulmonary hypertension. J Physiol. 2016;594:1167–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dean A, Gregorc T, Docherty CK, Harvey KY, Nilsen M, Morrell NW, MacLean MR. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in Sugen 5416‐induced experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. James J, Murry DJ, Treston AM, Storniolo AM, Sledge GW, Sidor C, Miller KD. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of 2‐methoxyestradiol alone or in combination with docetaxel in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia Y, Choi HK, Lee K. Recent advances in hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐1 inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;49:24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang L, Zheng Q, Yuan Y, Li Y, Gong X. Effects of 17β‐estradiol and 2‐methoxyestradiol on the oxidative stress‐hypoxia inducible factor‐1 pathway in hypoxic pulmonary hypertensive rats. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13:2537–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dey P, Velazquez‐Villegas LA, Faria M, Turner A, Jonsson P, Webb P, Williams C, Gustafsson JA, Strom AM. Estrogen receptor beta2 induces hypoxia signature of gene expression by stabilizing HIF‐1alpha in prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sim J, Cowburn AS, Palazon A, Madhu B, Tyrakis PA, Macías D, Bargiela DM, Pietsch S, Gralla M, Evans CE, Kittipassorn T, Chey YCJ, Branco CM, Rundqvist H, Peet DJ, Johnson RS. The factor inhibiting HIF asparaginyl hydroxylase regulates oxidative metabolism and accelerates metabolic adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2018;27:898–913.e897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukui M, Zhu BT. Mechanism of 2‐methoxyestradiol‐induced apoptosis and growth arrest in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dubey RK, Tofovic SP, Jackson EK. Cardiovascular pharmacology of estradiol metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dubey RK, Jackson EK. Potential vascular actions of 2‐methoxyestradiol. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wright AF, Ewart MA, Mair K, Nilsen M, Dempsie Y, Loughlin L, Maclean MR. Oestrogen receptor alpha in pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;106:206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rafikov R, Sun X, Rafikova O, Louise Meadows M, Desai AA, Khalpey Z, Yuan JXJ, Fineman JR, Black SM. Complex I dysfunction underlies the glycolytic switch in pulmonary hypertensive smooth muscle cells. Redox Biol. 2015;6:278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li M, Riddle S, Zhang H, D'Alessandro A, Flockton A, Serkova NJ, Hansen KC, Moldvan R, McKeon BA, Frid M, Kumar S, Li H, Liu H, Cánovas A, Medrano JF, Thomas MG, Iloska D, Plecita‐Hlavata L, Ježek P, Pullamsetti S, Fini MA, El Kasmi KC, Zhang Q, Stenmark KR. Metabolic reprogramming regulates the proliferative and inflammatory phenotype of adventitial fibroblasts in pulmonary hypertension through the transcriptional co‐repressor C‐terminal binding protein‐1. Circulation. 2016;134:1105–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Angara S, Bhandari V. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in lung diseases: emphasis on mitophagy. Front Physiol. 2013;4:384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kambhampati S, Banerjee S, Dhar K, Mehta S, Haque I, Dhar G, Majumder M, Ray G, Vanveldhuizen PJ, Banerjee SK. 2‐methoxyestradiol inhibits Barrett's esophageal adenocarcinoma growth and differentiation through differential regulation of β‐catenin‐E‐cadherin‐axis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:523–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aquino‐Galvez A, Gonzalez‐avila G, Delgado‐Tello J, Castillejos‐Lopez M, Mendoza‐Milla C, Zuniga J, Checa M, Maldonado‐Martinez HA, Trinidad‐Lopez A, Cisneros J, Torres‐Espindola L, Hernandez‐Jimenez C, Sommer B, Cabello‐Gutierrez C, Gutierrez‐Gonzalez LH. Effects of 2‐methoxyestradiol on apoptosis and HIF‐1α and HIF‐2α expression in lung cancer cells under normoxia and hypoxia. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:577–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fong YC, Yang WH, Hsu SF, Hsu HC, Tseng KF, Hsu CJ, Lee CY, Scully SP. 2‐methoxyestradiol induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human chondrosarcoma cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1106–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule‐binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Esteve MA, Carre M, Braguer D. Microtubules in apoptosis induction: are they necessary? Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:713–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Parker AL, Kavallaris M, McCarroll JA. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carbonaro M, Escuin D, O'Brate A, Thadani‐Mulero M, Giannakakou P. Microtubules regulate hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α protein trafficking and activity: implications for taxane therapy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11859–11869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karna P, Rida PCG, Turaga RC, Gao J, Gupta M, Fritz A, Werner E, Yates C, Zhou J, Aneja R. A novel microtubule‐modulating agent EM011 inhibits angiogenesis by repressing the HIF‐1α axis and disrupting cell polarity and migration. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1769–1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cushman M, He HM, Katzenellenbogen JA, Lin CM, Hamel E. Synthesis, antitubulin and antimitotic activity, and cytotoxicity of analogs of 2‐methoxyestradiol, an endogenous mammalian metabolite of estradiol that inhibits tubulin polymerization by binding to the colchicine binding site. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2041–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Magiera MM, Janke C. Post‐translational modifications of tubulin. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R351–R354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huff LM, Sackett DL, Poruchynsky MS, Fojo T. Microtubule‐disrupting chemotherapeutics result in enhanced proteasome‐mediated degradation and disappearance of tubulin in neural cells. Can Res. 2010;70:5870–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prins KW, Tian L, Wu D, Thenappan T, Metzger JM, Archer SL. Colchicine depolymerizes microtubules, increases junctophilin‐2, and improves right ventricular function in experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006195 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ventetuolo CE, Baird GL, Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Fritz JS, Hill NS, Klinger JR, Lima JA, Ouyang P, Palevsky HI, Palmisciano AJ, Krishnan I, Pinder D, Preston IR, Roberts KE, Kawut SM. Higher estradiol and lower dehydroepiandrosterone‐sulfate levels are associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension in men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baird GL, Archer‐Chicko C, Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Foderaro AE, Fritz JS, Hill NS, Kawut SM, Klinger JR, Lima JAC, Mullin CJ, Ouyang P. Lower DHEA‐S levels predict disease and worse outcomes in post‐menopausal women with idiopathic, connective tissue disease‐ and congenital heart disease‐associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1800467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Expanded Materials and Methods.

Table S1. Patient Details of Non‐PAH Male and Female hPASMCs Used Within This Study

Table S2. Antibodies and Dilutions Used for Western Blotting (WB) or Immunofluorescence (IF)

Table S3. Probe Sets Used Within This Study and Taqman Assay ID Details

Figure S1. HIF1α signaling in female hPASMCs. mRNA transcript expression levels of HIF1α (A) prolyl hydroxylase 1 (PHD1; B), prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2; C), prolyl hydroxylase 3 (PHD3, D), Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL; E) and factor‐inhibiting HIF (FIH, F). Effect of 72 hours treatment with 100 nmol/L E2 on FIH mRNA expression in male (G) and female (H) hPASMCs. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ★P<0.05; ★★P<0.01 determined by unpaired or paired t‐test. hPASMC indicates human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

Figure S2. Effect of 2ME2 on the cellular proliferation of rat PASMCs. Effect of 2ME2 (100 nm–10 μmol/L) on fetal bovine serum–induced proliferation in isolated rat female PASMCs assessed by manual cell counts (A) and CCK8 assay (B) after 48 hours (n=5 and 4, respectively). Data are shown as mean±SEM. ★P<0.05; ★★P<0.01; ★★★P<0.001 determined by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells;Veh, vehicle.

Figure S3. Effects of 2ME2 on proapoptotic genes in female hPASMCs. Effect of 2ME2 (10 μmol/L, 48 hours) on mRNA transcript expression levels of caspase 9 (A) and p53 (B) in female hPASMCs. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II mRNA (C) and protein expression (D) in female PASMCs. Data is shown as mean±SEM. Statistical analysis determined by paired t‐test. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMCs, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S4. Morphological changes in female hPASMCs associated with 48 hours 2ME2 treatment. Bright field images after 1% CSS (A), 5% CSS (B), 100 nmol/L 2ME2 (C), 1 μmol/L 2ME2 (D), 10 μmol/L 2ME2 (E) and vehicle (F). Cellular perimeter measurements in female hPASMCs in presence of 10 μmol/L 2ME2 (G) (n=3). Scale bar indicates 70 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; CSS, charcoal‐stripped serum; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; Veh, vehicle.

Figure S5. Comparison of morphological changes in female hPASMCs after stimulation with various microtubule mediators. Bright field images after 24 hours treatment with Taxol (10 μmol/L), colchicine (10 μmol/L), and 2ME2 (10 μmol/L) (n=3). Scale bar indicates 70 μm. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S6. Effects of microtubule mediators on α‐tubulin organization in female hPASMCs. High‐resolution confocal microscopy images of α‐tubulin after treatment with Taxol (10 μmol/L), colchicine (10 μmol/L) and 2ME2 (10 μmol/L) (n=3) with increased digital magnification (inset). Arrows indicate condensing/disruption to the microtubule network. Scale bar indicates 10 and 5 μm (inset). 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; hPASMC, human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure S7. Schematic representation of 2ME2 mechanisms of action in female hPASMCs. 2ME2 causes α‐tubulin dysregulation, which in turn can cause reduced HIF1α and HK2 protein expression. Disruption of α‐tubulin may also lead to increases in apoptotic genes Bax and RIPK1 and activation of caspase 3/7. Green arrow, upregulation. Red arrow, down regulation. Blue arrow, causes/leads to. 2ME2 indicates 2‐methoxyestradiol; HK2, hexokinase 2; Bax, Bcl‐associated X; RIPK1, receptor‐interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 1.