Abstract

The bioavailability and bioaccumulation of sedimentary hydrophobic organic compounds (HOCs) is of concern at contaminated sites. Passive samplers have emerged as a promising tool to measure the bioavailability of sedimentary HOCs and possibly to estimate their bioaccumulation. We thus analyzed HOCs including organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/furans (PCDD/Fs) in sediment, porewater and riverwater using low density polyethylene (LDPE) passive samplers, and in 11 different finfish species and blue crab from the lower Passaic River. Additionally, perfluorinated alkyl acids (PFAAs) were measured in grab water samples, sediment and fish. Best predictors of bioaccumulation in biota were either porewater concentrations (for PCBs and OCPs), or sediment organic carbon (PBDEs and PFAAs), including black carbon (OCPs, PCBs and some PCDD/F congeners) normalized concentrations. Measured lipid-based concentrations of the majority of HOCs exceeded the chemicals’ activites in porewater by at least 2-fold, suggesting dietary uptake. Trophic magnification factors were > 1 for moderately hydrophobic analytes (log KOW = 6.5 – 8.2) with low metabolic transformation rates (< 0.01 day−1), including longer alkyl chain PFAAs. For analytes with lower (4.5 – 6.5) and higher (>8.2) KOWs, metabolic transformation was more important in reducing trophic magnification.

Keywords: HOCs, bioaccumulation, porewater, PFASs, sediment

INTRODUCTION

Rivers in highly urbanized/industrialized areas are impacted by various classes of chemicals, often resulting in adverse ecological effects, such as habitat destruction, and various physiological and reproductive disorders in the river fauna. Once in the ecosystem, pollutants can accumulate in biota from the surrounding water, sediments and/or porewater depending on the physicochemical properties of the pollutants, feeding habits, trophic position and metabolic rates. The significance of bioaccumulation in fish and the accompanied ecological and human health risks have been previously highlighted in studies performed by the U.S. EPA (US EPA 1992a; US EPA 1992b). Typically, organic chemicals are prioritized with respect to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential and toxicity (PBT chemicals) (Gobas et al. 2009). Recently, the use of chemical properties to predict the bioaccumulation potential of a chemical has been questioned (Borgå et al. 2012).

In our recent work (Khairy et al. 2014), we assessed the biomagnification of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin/dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) in fish and crabs collected from the Passaic River estuary. In general, the dominant exposure pathways for legacy hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs) in biota were porewater and sediments rather than the riverwater. Here, we aimed to expand on these results by investigating a wider range of contaminants with more diverse structures and properties. Targeted compounds include organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and perfluorinated alkyl acids (PFAAs), including perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA). As PFAAs and some OCPs display much greater aqueous solubility than the legacy HOCs, it is unclear whether sediment-bound contamination remains a primary exposure pathway to biota in the river. These compounds also cover a wide range of resistance to metabolism (US EPA 2016a), which should, in conjunction with varying degrees of lipophilicity, affect their uptake and magnification in the food web.

While recent work established the presence of PBDEs at relatively high concentrations in all the environmental compartments of the lower Passaic River, and deduced diffusive fluxes of PBDEs from sediment to overlying water (Khairy and Lohmann 2017), little is known regarding their uptake sources and their bioaccumulation potential.

Unlike legacy HOCs, PFAAs are ionic, amphiphilic compounds (Key et al. 1997), and thus have different physicochemical properties. They have been globally detected in all environmental compartments (Labadie and Chevreuil 2011; Loi et al. 2011; Fang et al. 2014). PFAAs are persistent and tend to bioaccumulate (PFAAs with longer fluorinated carbon chain) (Conder et al. 2008), undergo long range transport (LRT) and cause adverse ecological and health effects (Lau et al. 2007). Anionic PFAAs are proteinophilic and generally found at highest concentrations in blood and liver (Becker et al. 2010) in contrast to the lipophilic legacy pollutants.

Studying the bioaccumulation potential of HOCs requires the ability to measure the freely dissolved fraction in sediments (porewater) and/or the water column, where bioavailability is expected to increase with an increase in the dissolved concentrations (You et al. 2006). Passive samplers, such as low density polyethylene (LDPE) sheets, have emerged as an inexpensive and effective technique for measuring the freely dissolved concentrations of HOCs. Traditionally, geochemical approaches have been used to predict porewater concentrations (sediment concentrations and organic carbon content), due to the difficulties associated with the measurement of the dissolved fraction in sediment’s porewater directly. However, since the development of passive sampling devices, estimation of porewater concentrations have become feasible ( Fernandez et al. 2009; Ghosh et al. 2014; Khairy and Lohmann 2017).

The original equilibrium partitioning theory (Di Toro et al. 1991) linked porewater concentrations of HOCs to their accumulation in the lipid of organisms. As LDPE samplers similarly accumulate HOCs from porewater, recent studies indicated that LDPE concentrations of HOCs (at equilibrium) can be used to predict their bioaccumulation (Friedman et al. 2009). In fact, recent work by Jahnke et al. (2014) suggested that passive sampling can be used to estimate the bioaccumulation potential of HOCs, and indicated that the majority of studies resulted in tissue concentrations below the equilibrium concentration with porewater (Jahnke et al. 2014). Being able to rely on passive samplers to predict (maximum) bioaccumulation in aqueous foodwebs would certainly be very useful for the assessment of contaminated sites.

In the current study, we investigated the bioaccumulation of OCPs and PBDEs in 11 fish species and Callinectes sapidus (blue crab), collected from the fresh-brackish portion of the Passaic River estuary. PFAAs data for only 8 fish species were included in the current study. To that end, we calculated the bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) for OCPs, PBDEs and PFAAs, compared the accumulated amounts of HOCs in LDPE and in the biota and investigated the best predictors for HOCs and PFAAs in biota using sediment geochemistry and LDPE (active water samples for PFAAs). Since sampling of biotic and abiotic compartments were done at the same time intervals and all the samples were analyzed in the same lab, we present here a uniquely consistent set of BAFs. Our objectives were to (i) assess the sources of contaminants accumulated by the biota (sediments, porewater, diet, or overlying water), (ii) assess the suitability of using LDPE to predict the bioaccumulation of HOCs in biota and (iii) derive bioaccumulation factors and assess the trophic magnification (or dilution) of target analytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples collection, extraction, analysis for OCPs and PBDEs

Detailed description of the sampling of biota and sediments, preparation and deployment of the LDPE in the river water (for OCPs and PBDEs), the stable isotope analysis in the biota tissues, the determination of porewater concentrations using LDPE tumbling experiment and the uncertainty analysis can be found in in Figures S1-S3, Table S1,text in the Supplementary information (SI) and in Khairy et al. ( 2014, 2015) and Khairy and Lohmann (2017). More information about the extraction of all matrices, instrumental analysis, quality assurance and the determination of porewater concentrations is available in the SI (Tables S2-S6) and is briefly summarized below.

Finfish specimens (n = 350 representing 10 species) including benthic feeders (Callinectes sapidus, Anguilla rostrata, Fundulus heteroclitus, Hybognathus regius, Morone americana), bentho-pelagic taxa (Fundulus diaphanus, Lepomis spp., Esox americanus, and juvenile Morone saxatilis), and pelagic species (Menidia menidia and Dorosoma cepedianum) and 7 Callinectes sapidus (blue crab) specimens were collected during August-November, 2011 at three locations in the Passaic River estuary (Figure S1). For marine transients, fish collections were restricted to the extent practical to young-of-year that had a recent history of exposure to contaminants in the system. See Table (S1) for more details on the biota samples.

Sediment samples were collected from 18 different locations (Figure S2) along the lower Passaic River during September to November, 2011, from the mudflats at low tide. Detailed description of the sampling methodology and sampling locations can be found in Khairy et al. (2015). Total organic carbon (TOC) and black carbon (BC) content in the sediments were determined as detailed in Gustafsson et al. (1997).

LDPE passive samplers were fastened to an anchored rope and suspended in the water column ~ 1–2 m below the surface at six different locations along the lower Passaic River (Figure S1) to sample the freely dissolved OCPs and PBDEs.

Freely dissolved porewater concentrations were determined by shaking (equilibrating) LDPE passive sampling sheets (25 μm thick) with sediment-water (containing sodium azide as a biocide) slurry for 9 weeks according to the method detailed in Lohmann et al. (2005).

Biota and sediment samples were extracted and subjected to cleanup according to the methods detailed elsewhere (Khairy et al. 2014, 2015). LDPE (both deployed in the river water and porewater) were cold extracted twice (24 hours each) in dichloromethane followed by hexane, concentrated and were not subjected to any further cleanup steps.

Collection of water samples, extraction and analysis of all the samples for PFAAs

We used the same sediment and biota samples that were collected for OCPs and PBDEs. Water samples (~ 20 cm below the surface) were collected in pre-cleaned (inner walls were cleaned with basic methanol followed by methanol and left overnight to dry) one-liter polypropylene bottles with polypropylene lids at 8 different locations along the lower segment of the Passaic River (Figure S3). Samples were kept in an ice bath until preserved in a freezer for analysis. Water samples (400 mL each) were analyzed for PFAAs (PFHxA - PFDoDA, PFBS, PFHxS and PFOS) in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Laboratory in Maryland (USA) according to the method detailed in Young et al. (2013). Sediments and fish samples were analyzed at University of Rhode Island (URI), USA. Extraction and cleanup was done according to the U.S. EPA method for the analysis of PFAAs (EPA 2011) (see SI, Tables S2 and S3 for more information). PFAAs were measured in 8 fish species [Morone saxatilis (29 – 33 cm), Anguilla rostrate (110 cm), Morone Americana (8 −16 cm), Fundulus diaphanous, Hybognathus regius, Menidia menidia, Dorosoma cepedianum, and Fundulus heteroclitus], but not in the blue crabs due to a lack of extra tissue after PBDE and OCP analysis.

Quality assurance

Procedural blanks, field blanks (LDPE), matrix spikes, and duplicate samples (20% of the total samples) were included with each sample batch and were carried throughout the entire analytical procedure in a manner identical to the samples. BDE-47 was detected in the blanks (10–20 % of the least detected concentration in the different matrices). Similarly, detected PFAAs in the blank samples were 12–25 % of the sample concentrations and accordingly, correction of samples for the blank detects was performed.

Recoveries of the surrogate standards in the biota, LDPE and sediment samples generally ranged from 65 – 102% and 72–104 % for OCPs and PBDEs respectively. Matrix spikes recoveries (Table S4) ranged from 94 – 104 % for OCPs and PBDEs with RSD % < 10 %. Reproducibility of the results ranged from 7.0 – 17 % and 5.0 – 18.5 % for OCPs and PBDEs respectively.

Recoveries of PFAAs in the matrix spikes (Table S5) were 87–133% for the majority of the target PFAAs and < 55 % for C13 - C18- perfluorocarboxylic acid and C10-perfluorosulfonate. Accordingly, these PFAAs were excluded from the discussion. Recoveries of the surrogate standards ranged from 57 – 120 % (Table S5). Limit of detection (LOD) corresponded to a signal-to-noise ratio of 3 (Table S6). Variability between duplicates was <20%.

Physicochemical properties

Octanol-water partitioning coefficient (Kow) values of OCPs were obtained from Schenker et al. (2005). Kow values for PBDEs were obtained from Yue and Li (2013). Polyethylene-water partitioning coefficients (KPE-W) for OCPs and PBDEs were obtained from Lohmann (2012). Lipid-water partitioning coefficients (Klip-w) were estimated from KOW according to the method of Endo et al. (2011). Organic carbon-water partitioning coefficient (KOC) were calculated as shown in Xia (1998).

For PFAAs, KOC were obtained from obtained from Higgins and Luthy (2007). Missing values were obtained by correlating the available values against those obtained from Labadie and Chevreuil (2011). Protein-water partitioning coefficients (KPW) were obtained from Kelly et al. (2009). Missing values were obtained from correlating the available values against KOCs (n = 8; R2 = 0.98); KOW values were obtained from Wang et al. (2011). KPW rather than Klip-w were used with PFAAs as these compounds bind to proteins rather than to general lipids. All the physicochemical properties used in the current study are given in Table S7.

Estimated compound specific metabolic biotransformation rates (Kmtrs) normalized to 10 g tissue weight were obtained from the BCFBAF function in EPI Suite 4.11 (US EPA 2016b).

Calculation of BAFs, TMFs and predicting biota concentrations

Bioaccumulation factors (BAFs, L/kg lipid or ww) were calculated as the ratio of lipid normalized tissue concentrations of PBDEs and OCPs (Clip, ng/kg lipid) to the freely dissolved river water concentrations from PE-samplers (Cw, ng/L), or fresh weight concentrations of PFAAs (; ng/kg ww) to grab water sample concentrations (Cw, ng/L) as follows (equation 1) (Schwarzenbach et al. 2005):

| (1) |

TMF values were calculated as follows (equation 2):

| (2) |

where b is the slope of the linear relationship between the natural log of lipid-normalized tissue concentrations and the trophic position of each species. TMFs >1 indicates that contaminants are biomagnifying whereas values < 1 indicate that contaminants are not taken up by the organism or that they are metabolized (trophic dilution).

Lipid-based concentrations (ng/g) of HOCs were estimated from each sediment’s sorbent phase [organic carbon (OC) and black carbon (BC)], porewater LDPE, and riverwater LDPE and compared to those measured in tissues (Clip) as follows: (equation 3–5):

| (3) |

Where, Csed is the sediment concentration (ng/g) and fOC is the fraction of OC in sediments. Similarely, lipid concentrations based on OC + BC (Clip,OC+BC) were estimated using a Freundlich coefficient of n = 0.7:

| (4) |

where fBC is the fraction of BC in the sediment and KBC is the black carbon-water partitioning coefficient. We used site specific KBC values in the current study.

Lipid concentrations from PE-derived porewater [Clip(PW)] and riverwater [Clip,(W)] were estimated as follows:

| (5) |

For PFAAs, protein-based concentrations were predicted only from sediment’s OC and from river water using equations 3 and 5. In both equations, Klip-w was replaced with KPW. Concentrations of PFAAs in the samples were normalized to a generic total protein content (25 %) assigned for fish tissues as shown in Kelly et al. (2009) and references therein.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical tests (ANOVA, t-test and correlations) were performed with SigmaPlot (version 11, Germany); regression analysis with IBM SPSS V25.

RESULTS

Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainties associated with the estimated porewater and river water concentrations (equation S4) from LDPE ranged from 41 – 65 % and 40 – 64 % respectively. Uncertainties associated with predicted tissue concentrations from sediment’s OC were the lowest (22 – 58 %) followed by predicted concentrations from porewater (41 – 65 %), river water (40 – 80 %) and sediment’s OC + BC (28 – 88 %).

Concentration of organic pollutants

OCPs:

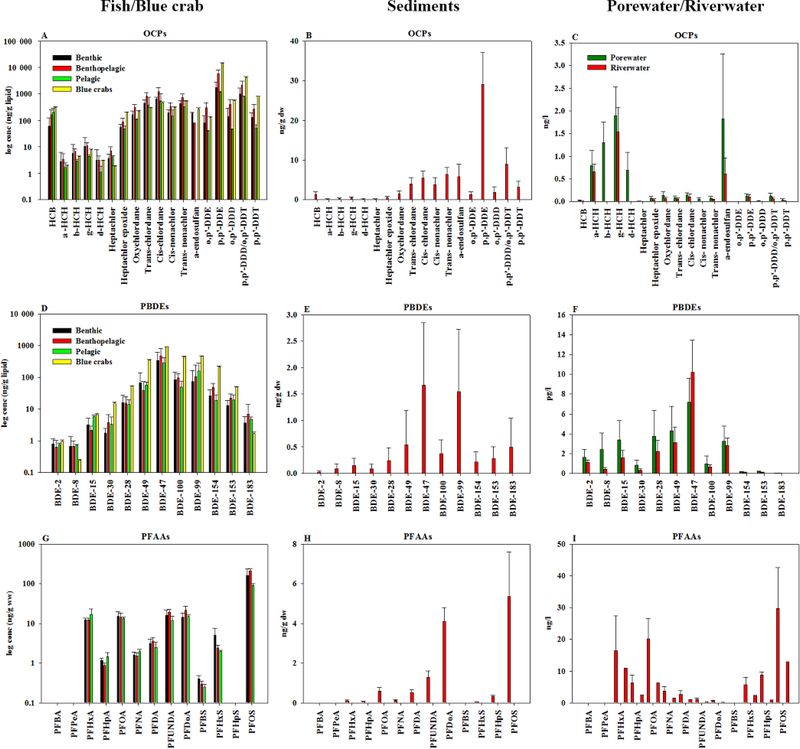

OCP concentrations in the biota samples are given in Figure 1A-C and Table S8. In all species, the following descending order was observed: DDTs (900 – 21,000 ng/g lipid) > chlordanes (840 – 4,700 μg/g lipid) > hexachlorobenzene (HCB) (11 – 330 ng/g lipid) > α-endosulfan (<LOD – 290 ng/g lipid) > HCHs (8.0 – 83 ng/g lipid). Concentrations of HCB, α-endosulfan and DDTs were 2.0 – 10 times higher in the blue crab samples (Figure 1A) than the other biota as was previously observed for PAHs, PCBs and PCDD/Fs (Khairy et al. 2014). Average concentrations of HCB in the benthopelagic (including the top predator) and pelagic species (164 and 200 ng/g lipid respectively) were 3.0 fold higher than in the benthic species (70 ng/g lipid). Similarly, average concentration of DDTs in the benthopelagic species (9,000 ng/g lipid) was 3.0–4.0 fold higher than in benthic (3,000 ng/g lipid) and pelagic species (2,000 ng/g lipid; Figure 1A).

Figure 1:

Concentrations of OCPs, PBDEs and PFAAs in fish/blue crabs (A, D, G), sediments (B, E, H) and porewater/riverwater (C, F, I) of the lower Passaic River.

DDTs (24–52 ng/g dw) were the dominant pesticide in the sediment samples (Table S9), followed by chlordanes (12–35 ng/g dw) and α-endosulfan (1.0 – 11 ng/g dw). In the porewater (Table S10) and surface water samples (Table S11) HCHs (2.6 – 9.0 and 1.4 – 3.1 ng/L respectively) dominated followed by α-endosulfan (0.20 – 5.7 and <LOD – 0.90 ng/L) and chlordanes (0.30 – 1.1 and 0.16 – 0.48 ng/L).

PBDEs:

Σ12PBDEs concentrations ranged from 120 ng/g lipid (Fundulus heteroclitus) to 2,500 ng/g lipid (Callinectes sapidus) in the biota (Table S12), 1.0–11 ng/g dw in sediments (Table S13), 19 – 40 pg/L in porewater (Table S14) and 12 −31 pg/L in surface water (Table S15). All the biotic, sediment, porewater and surface water samples were dominated by BDE-47 and BDE-99 (Figure 1D-F). Other congeners that were detected included BDE-183 in sediments, and BDE-100 and BDE-49 in the biota, sediments and porewater (estimated by LDPE).

PFAAs:

Concentrations of PFAAs ranged from 130 ng/g ww (Fundulus heteroclitus) to 350 ng/g ww (Anguilla rostrata) (Table S16). All the samples were dominated by PFOS (52 – 76 % of the total PFAA, Figure 1G) followed by PFDoA, PFUnDA, PFOA (4.0 – 10 % each) and PFHxA. PFBA, PFPeA and PFHpS were below LOD in all the samples. In all samples, concentrations of perfluorinated sulfonic acids (PFSAs) were significantly (t- test, p < 0.05) higher than perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs).

PFAAs in the sediment (Figure 1H) samples ranged from 8.0 ng/g dw (km 3.7) to 15 ng/g dw (km 24) (Table S17). PFOS was the dominant compound (42 % of total concentrations). The longer chain PFCAs (PFDoA: 35 %; PFUnDA:11 %), PFOA (5.0 %) and PFDA (4.0 %) were easily detected in sediment, probably related to their greater affinity for particles and hence accumulation in sediments (sorption to OC) due to increasing hydrophobicity with increasing number of CF2 groups (Ahrens et al. 2010). PFBA, PFPeA and PFBS were below LOD in all the samples, whereas PFHpA and PFHpS were below LOD in the majority of the samples.

Concentrations of PFAAs in the surface water ranged from 44 ng/L (km 3.7) to 120 ng/L (km 22.4) (Table S17). Similar to results for sediments and biota, PFOS dominated in surface water samples, followed by PFOA and PFHxA (Figure 1I).

Tissue concentrations versus abiotic compartments

LDPE concentrations of HOCs [in riverwater (CPE(RW)) and porewater (CPE(PW))] at equilibrium (ng/kg PE), OC-normalized sediment concentrations (Csed(OC); ng/kg OC), BC-normalized sediment concentrations (Csed(BC); ng/kg BC) and OC+BC-normalized sediment concentrations (Csed(OC+BC)) were compared with lipid-normalized concentrations (Clip) of the target analytes in the food web of the lower Passaic River (Figure S4). For PFAAs, the comparison was only made with Csed(OC). Significant linear relationships were observed between log measured Clip and log CPE(RW) (Figure S4A), log CPE(PW) (Figure S4B) and log sediment (Figure S4C-E) concentrations (including PFAAs). Coefficient of determinations (R2) ranged from 0.79 to 0.82 and slopes of the best fits were insignificantly different from 1 (slopes = 1.2–1.3, p < 0.001).

Clip for all HOCs were predicted from equations 3–5 using the OC (Clip(OC)) and the OC + BC models (Clip(OC+BC)), porewater (Clip(PW)) and riverwater (Clip(RW)) LDPE (Figure 2) and compared to measured concentrations. Similarly, protein-based tissue concentrations of PFAAs were predicted from Clip(OC) and Clip(RW) based on measured riverwater concentrations. To facilitate the comparison between HOCs and PFAAs, measured (in biota) and predicted protein-based concentrations of PFAAs from sediment and riverwater were normalized to the lipid content. This step was done by converting the predicted protein-based concentrations (from abiotic compartments) to equivalent wet weight concentrations and then normalizing to the measured lipid content in tissues. In addition to the regression lines, a factor difference of ± 10 (represented by the dashed red lines) was used to evaluate the predictive ability of the abiotic compartments. This factor was previously used to evaluate the ability of using passive samplers as a surrogate for bioaccumulation of HOCs (Joyce et al. 2016). When points occur within the dashed lines, it indicated similarities in the affinities of geochemical natural sorbents (OC and BC), lipid and LDPE to the organic pollutants. Mono-through tri-chlorinated dioxins and furans and HCHs were excluded from the comparison because of their high biotransformation potential and/or uncertainties in the physicochemical properties.

Figure 2:

Measured versus model-predicted lipid-based concentrations of OCPs, PCBs, PCDD/Fs, PFAAs and PBDEs in fish/blue crabs based on partitioning from (A) sediment OC, (B) sediment OC + BC, (C) porewater, and (D) riverwater in the lower Passaic River. Points represent the average values for all fish/blue crabs; error bars represent the standard deviation; dashed red lines represent the 95 % prediction intervals.

Highly significant linear relationships (all regression parameters are shown in Figure 2) were observed between log measured Clip and predicted log Clip(OC) (Figure 2A), Clip(OC+BC) (Figure 2B) and Clip(PW) for HOCs only (Figure 2C) and Clip(RW) (Figure 2D) for all species. In general, PCDD/Fs were less well predicted than other classes of pollutants.

Jahnke et al. (Jahnke et al. 2014) used passive samplers to derive the chemical activity of several PCBs and HCB in sediment and biota and to investigate the possibility of using passive samplers as a metric for the thermodynamical potential for the bioaccumulation of HOCs. According to their results and other cited studies, measured Clip/predicted Clip from porewater were either below or near their equilibrium benchmark values (0.5 – 2.0). In the current study, 2,3,7,78-TCDD, 2,3,7,8-TCDF, PCB 52, 101, 105, 118, 128, 138, 153, 180 and 187, BDE-28, 49, 47, 100, 154, HCB, chlordanes and DDTs in the majority of the fish and blue crab samples showed values greater than the equilibrium benchmark based on porewater (> 2).

Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of HOCs and PFAAs

Calculated BAFs for OCPs, PBDEs (both in L/kg lipids) and PFAAs (in L/kg PW) are given in Tables (S18 – S20). Average BAFs ranged from 4.1 × 103 (α-HCH) – 7.7 × 107 (o,p’-DDE), 7.1 × 105 (BDE-2) – 5.3 × 108 (BDE-154) and 4.8 × 102 (PFBS) – 1.1 × 105 (PFDoA) for OCPs, PBDEs and PFAAs respectively. Calculated BAFs for PBDEs were the highest (Table S18) followed by OCPs (Table S19) and PFAAs (Table S20). Additionally, PBDE BAFs were higher than those previously calculated for PAHs in the same samples (Khairy et al. 2014) but lower than BAFs previously calculated for PCDD/Fs (4.0 × 103 – 6.0 × 108) (Khairy et al. 2014) and PCBs (2.0 × 103 – 2.0 × 109) (Khairy et al. 2014). Reported BAF values for OCPs and PBDEs in the current study were higher than values previously reported for freshwater fish from China (2.0 × 103 – 8.0 × 105 and 2.0 × 102 – 3.2 × 106 for OCPs and PBDEs respectively) (Wu et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012) and for Lake Trout in Lake Michigan (Streets et al. 2006). Calculated BAFs for PFAAs were within the range of values calculated for PFAAs in literature (1.2 × 101 - 1.0 × 105) (Kwadijk et al. 2010; Labadie and Chevreuil 2011).

Trophic levels of the fish species were calculated here based on the levels of nitrogen isotopes in the tissues (Khairy et al. 2014). Blue crabs were excluded because of their relatively high detected concentrations of OCPs and PBDEs despite of their low trophic position, which is probably due to accidental sediment ingestion. Calculated TMFs were significantly greater than 1 (p < 0.05) for o,p’-DDD (4.1), HCB (3.9), o,p’-DDE (3.6). p,p’-DDE (3.1), p,p’-DDT (2.1), heptachlor (2.0), oxychlordane (1.8), BDE-47 (3.1), BDE-154 (2.5), Σ12PBDEs (2.4), and BDE-100 (2.1) (Table S21).

DISCUSSION

Comparing tissue concentrations to sediment, riverwater and porewater concentrations

In this study, significant linear relationships were observed between log CPE(PW), CPE(RW), Csed(OC) and Csed(OC+BC) and log Clip in biota. Similar relationships were previously observed for PCBs (Friedman et al. 2009; Joyce et al. 2015; Joyce et al. 2016) and PBDEs (Joyce et al. 2015) when tissue concentrations were compared to LDPE concentrations adjusted for equilibrium. Coefficients of determination (R2) reported in the current study (for all classes of HOCs + PFAAs in sediments) were within the range previously observed for PCBs (0.59–0.94) (Friedman et al. 2009; Joyce et al. 2015; Joyce et al. 2016) and DDTs (0.72) but higher than for PBDEs (0.59) (Joyce et al. 2015).

In contrast, slopes of the regression lines in the current study (1.2 – 1.3, p < 0.001) were higher than those observed in the previous studies for PCBs, PBDEs and DDTs (0.74 – 1.0) (Friedman et al. 2009; Joyce et al. 2015; Joyce et al. 2016). The slopes we observed indicated that accumulated amounts of HOCs in tissues exceeded those predicted from LDPE or sediment geochemistry. This implies that biotransformation of most HOCs did not play a significant role in the fish samples collected from the lower Passaic River. These results suggest that the linear relationships with abiotic compartments could be used to predict the bioaccumulation potential in the fish. Best predictions of Clip for HOCs and PFAAs were obtained from either Csed(OC+BC) and/or CPE(PW) (Figure 2), as demonstrated by higher R2, lower SE and slopes closer to 1.

All the OCPs, PFAAs and the majority of PBDE, PCDD/F and PCB congeners occurred within a factor of 10 of measurements, although lipid-based concentrations were overestimated for many congeners. Importantly, PFAAs were not separated from the other HOCs and the regression parameters with and without PFAAS did not differ (Figure 2). This possibly implies a similar affinity of HOCs and PFAAs to OC. Moreover, tissue concentrations of PFOA through PFDoA, PFOS and PBDEs were well predicted from Csed(OC)within a factor difference ranging from 1.0 to 2.8 (Figure 2A).

Lipid-normalized concentrations of OCPs and PCBs were similarly better predicted using the CPE(PW) and Csed(OC+BC) models (Figure 2B, C) within a factor difference of 1.0 – 4.0. Higher factor differences (measured /predicted > 2.0) was observed for some PCB congeners (PCB 28, 52, 101, 153, 138, 180, which are known to be strong bioaccumulative) and OCPs such as chlordanes and DDTs. presumably due to their uptake from food and their biomagnification potential (see below). As for OCs, regression parameters for the measured versus predicted tissue concentrations from riverwater were similar with and without adding PFAAs (Figure 2D), which again indicates a similar lipid-water partitioning behavior for HOCs and the more polar PFAAs. However, many PFAAs were underestimated by riverwater, with factor differences (measured/predicted) > 10. Only the more soluble PFHxA and PFHpA were better predicted from riverwater (factor difference: 1.5 – 2.5) than sedimentary OC, Csed(OC). Unfortunately, concentrations of PFAAs were not measured in porewater and the predictive ability of CPE(PW) and Csed(OC+BC) cannot be examined. However, based on regression output of Csed(OC) and CPE(RW), we assume that the uptake of PFAAs probably occurred from porewater and diet similar to HOCs.

When comparing measured to predicted concentrations of the legacy pollutants, we did not account for the biotransformation rates in the biota. We assumed biotransformation was negligible for several reasons: First, significant linear relationships were observed between calculated log bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) and log KOWs (Figure 3) indicating either equilibrium or steady state for the HOCs. Second, as shown in Figure 3, log BAFs for all the analytes (except BDE-99) were above the 1:1 line. In other words, calculated log BAFs were higher than their corresponding log KOWs, which is an indicative of low/non-biotransformation except for BDE-99. Third, lipid-based concentrations of HOCs were higher than sediment concentrations (normalized to OC, BC and OC + BC) and LDPE concentrations (ng/kg PE) (Figure S4). Finally, Wirgin et al. (2011) indicated that fish in the Hudson River, which is located in the same region of the Passaic River, have developed a mechanism to resist biotransformation due to evolutionary changes from the exposure to legacy pollutants.

Figure 3:

Linear regression relationships between log KOW and log BAFs calculated for OCPs and PBDEs based on riverwater (A), porewater (B), for PFAAs based on riverwater (C), and log BAFs against number of fluorinated carbons for PFAAs (D). TSCA: toxic substance control act.

Comparison of porewater and foodweb chemical activities

In contrast to other studies [25 and references therein], measured Clip of the majority of the HOCs in the current study were higher than the porewater’s equilibrium benchmark set by Jahnke et al (2014). The benchmark value was derived as a factor of 2 of the chemicals’ activites in porewater as estimated by passive samplers in sediment and biota directly. Possible reasons for these divergent results in our study include (i) the structure of the foodwebs, (ii) the relative importance of pelagic vs trophic coupling, and (iii) relying on a different approach of comparing chemical activities in biota relative to abiotic compartments.

We rule out metabolism having a significant influence on these persistent chemicals as we mentioned in the previous section. Similarly, trophic levels in the Swedish lake’s food-chain were even greater (assumed to reach a TL of up to 4.4), than in the Passaic River, where the top predator was at a TL of 4.0 (Khairy et al. 2014).

We argue that the exceedance of porewater chemical benchmark observed in biota of the Passaic River is due to the strong benthic coupling, as we described previously (Khairy et al. 2014; Khairy and Lohmann 2017). In other words, the fish in the Swedish lake were likely strongly affected by water column concentrations (not measured), which we assume were much below porewater concentrations. In the Passaic River, differences between porewater and water column were only 0.6 – 11. Lastly, we inferred chemical activities in biota by lipid-normalizing HOC concentrations, while we used passive samplers in porewater and water column. This introduces more uncertainty, but the good agreement observed by numerous studies between lipid-normalized and passive sampler-derived HOC concentrations implies this is of minor importance (Friedman et al. 2009; Friedman and Lohmann 2014; Joyce et al. 2016). Overall, our results suggest that predicting the ecological risk to aquatic biota using measurements of porewater concentrations is not sufficient unless adjusted by the calculated BAFs in benthically-coupled system.

Bioaccumulation of the organic pollutants

Significant log BAFs – log KOW (R2 = 0.80 – 0.91; p < 0.001) and log BAFs – log Klip-w (R2 = 0.87 – 0.94; p < 0.001) linear relationships were observed for PBDEs and OCPs in the biota using both riverwater (BAFRW; Figures 3A, S5A) and porewater (BAFPW; Figures 3B, S5B) for calculating BAFs, indicating that the observed partitioning between lipids (in biota) and water can be approximated from the octanol – water equilibrium partitioning. In our previous work, we indicated and quantified diffusive fluxes of PBDEs from the porewater to the overlying riverwater, which could explain the tight coupling of HOC concentrations and profiles in porewater and riverwater (Figure 1). Lower log BAFsRW were generally observed for BDE-99 than for the tri- through hepta-brominated congeners (Figure 3A) possibly due to its biotransformation (metabolism) in fish species (Hu et al. 2010). Similar findings were previously observed in aquatic species collected from China (Wu et al. 2008) and in Lake Michigan’s trout (Streets et al. 2006). BDE-183 also showed lower BAF values compared to penta- and hexa-congeners, probably due to the limited uptake induced by its large molecular size. However, calculated log BAFsRW and BAFsPW for the majority of the fish samples were higher than their corresponding log KOWs (Figure 3) and log Klip-w (Figure S5) indicating a possible dietary uptake. We argue that the exceedance of KOW-predicted BAFsRW and BAFsPW is the result of the influence of the porewater on riverwater (via diffusive fluxes).

Calculated BAFs for PFAA increased significantly with increasing log KOW (Figure 3C) and alkyl chain length (Figure 4D; R2 = 0.60 – 0.65; SE = 0.42 – 0.45; p < 0.01). Log BAF of the longer chain PFUNDA, PFDoDA and PFOS (average: 4.1, 4.4 and 3.7 respectively) were generally higher than the shorter chain PFAAs. Additionally, values for PFOS were higher than all the PFAAs other than the above-mentioned long chain ones indicating a possible higher bioaccumulation potential for PFOS. Based on the TSCA bioaccumulation criteria (Hong et al. 2015), only the longer chain PFAAs and PFOS appear to be bioaccumulative to very bioaccumulative in the fish species. (3 ≤ log BAF< 5), which agrees well with other studies (Hong et al. 2015).

Figure 4:

3D plot showing the probability of having a trophic magnification factor (TMF) value > 1 based on the values of both metabolism (log kmtr) and octanol-water partitioning (log KOW). Blue color represents the greatest probability (100 %) and the dark orange color represent the least probability.

Biomagnification of pollutants in the food web

All the HOCs (DDTs, HCB, oxychlordane, BDE-47, 100, 154, some PCB and PCDD/F congeners) that showed significant trophic magnification potential (TMF > 1, p < 0.05) were the analytes that exceeded the equilibrium porewater benchmark value set by Jahnke et al. (2014) indicating the importance of the dietary intake and strong benthic coupling in the Passaic River. All the other investigated OCPs and PBDEs showed either insignificant trophic dilution (γ- and δ-HCH) or trophic magnification. For PFAAs (Table S22), significant trophic magnification was only observed for PFUnDA (1.9), PFOS (1.8), PFDA (1.6) and PFDoA (1.5), as was observed in previous studies (Fang et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2014). However, calculated TMFs for PFAAs were generally lower than values calculated for OCPs and PBDEs.

For PFCAs, TMF values were relatively stable for C5 - C8 perfluorinated acids, then increased for C8 - C10, but decreased again for PFDoA, which is probably due its molecular size, limiting its uptake. For PFSAs, PFOS showed the highest TMF value among all the PFAAs, which agrees well with previous findings in other food webs worldwide (Conder et al. 2008).

Role of metabolic transformation

To investigate the relationships between hydrophobicity, metabolic transformation (kmtr) and TMFs, a conditional probability table was computed using TMFs and presented graphically in Figure (4) based on cumulative frequencies. The figure indicated that the maximum probability of obtaining a TMF > 1 were observed for HOCs having log KOW > 7.5 and characterized by low metabolic transformation rates (kmtr ≤ 0.01 day−1). Starting from log KOW > 6.5, high probability rates of TMFs > 1 were observed. This range included dioxins, PCBs, PBDEs, OCPs and the longer alkyl chain PFAAs (> C8). Exceptions were observed at lower log KOWs (4.5 – 6.5) for some OCPs and higher molecular weight PAHs, but still at low metabolic transformation rates (log kmtr ≤ 1.25 equivalent to kmtr ≤ 0.06 day−1) indicating that at these lower KOW ranges, there is an increase in the importance of kmtr in controlling trophic magnification. Additionally, calculated TMFs for PCB 189, 195, 206 and 209 (1.4 – 1.97) were higher than TMF values calculated for OCDD, OCDF and BDE-183 (0.70 – 1.72) although all have log KOW values > 8.0 (8.02 – 8.79). This can be explained knowing that the latter group has higher biotransformation rates (log kmtrs: −1.96 to −1.46) than the former group (logkmtrs: −3.04 to −3.30). From all the investigated HOCs with TMFs > 1 (n = 59), only four had log kmtr > −1.5 (Kmtr > 0.032 day−1). All these findings suggest that kmtr values are probably more important than hydrophobicity in explaining the biomagnification of HOCs. The uncertainty related to the estimated kmtr values could be substantial, however.

CONCLUSIONS

Although banned decades ago, the contamination by legacy pollutants is widespread in the aquatic environment of the lower Passaic River. Our results indicate that CPE(PW) and CPE(RW) of HOCs and - for some HOCs and PFAAs - Csed(OC) can be used to estimate Clip in biota. In contrast to previous results, though, measured Clip in the current study were above the porewater equilibrium benchmark concentration (0.5–2). Our results imply that in systems with strong benthic coupling, bioaccumulation needs to be considered to predict HOC and PFAA concentrations in top predators. Measured tissue concentrations of PFOA, PFNA, PFUnDA, PFDoA and PFOS were 1.4 – 2.7 times higher than predicted tissue concentrations from sediment OC. This agrees well with their bioaccumulative nature as suggested by TSCA bioaccumulation criteria (Hong et al. 2015) and suggests dietary uptake. Both hydrophobicity and metabolic transformations are needed to assess the biomagnification potential for both the lipophilic contaminants and PFAAs. Future work should confirm how useful chemical acitivities in sediment are for being able to predict the chemicals’ body burden in a given foodweb. This will always depend on the specifics of the ecosystem under consideration, including variations in the environmental conditions, foodweb characteristics and the physicochemical properties of sediments in the area under investigation. Yet our study indicated that porewater concentrations from passive sampling for HOCs and/or sediment geochemistry for PDBEs and PFAAs were good predictors of lipid-normalized concentrations. There are additional factors, though, that will influence this predictive ability between sites and methods: first, variabilities arising from using different passive samplers and/or using unstandardized methods for the same passive sampler (Jonker et al. 2018); second, uncertainties associated with the use of partitioning coefficients in particular for compounds such as PFAAs that bind to proteins; and finally, expected differences from estimating porewater concentrations using in situ vs ex situ samplers. Accordingly, these factors should be addressed in future research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the Hudson River Foundation for funding this project (Hudson River Award # HRF 2011-5), partial support by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants P42ES027706 and SERDP grant ER 2538, and thank M. Weinstein and K. Barrett (Manhattan College) for sampling support.

Footnotes

Data availability statement:

Data pertaining to this manuscript are available in the Supplemental Data.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Data on sampling, chemical analysis, physicochemical properties, spatial distribution, BAFs and TMFs are available on the Wiley Online Library at DOI: 10.1002/etc.xxxx.

REFERENCES

- Becker AM, Gerstmann S, Frank H. 2010. Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Two Fish Species Collected from the Roter Main River, Bayreuth, Germany. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 84(1):132–135. doi: 10.1007/s00128-009-9896-0. [accessed 2016 Jun 14]. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00128-009-9896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgå K, Kidd KA, Muir DCG, Berglund O, Conder JM, Gobas FAPC, Kucklick J, Malm O, Powell DE. 2012. Trophic magnification factors: considerations of ecology, ecosystems, and study design. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 8(1):64–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Chaoyang, Li Loretta Y. 2013. Filling the gap: Estimating physicochemical properties of the full array of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Environ Pollut. 180:312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conder JM, Hoke RA, de Wolf W, Russell MH, Buck RC 2008. Are PFCAs Bioaccumulative? A Critical Review and Comparison with Regulatory Criteria and Persistent Lipophilic Compounds. Environ Sci Technol. 42(4):995–1003. doi: 10.1021/es070895g. [accessed 2016 Jun 14]. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es070895g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S, Escher B, Goss K 2011. Capacities of membrane lipids to accumulate neutral organic chemicals. Environ Sci Technol. 45(14):5912–5921. [accessed 2016 May 3]. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es200855w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA US. 2011. Draft Procedure for Analysis of Perfluorinated Carboxylic Acids and Sulfonic Acids in Sewage Sludge and Biosolids by HPLC/MS/MS.

- Fang S, Chen X, Zhao S, Zhang Y, Jiang W, Yang L, Zhu L 2014. Trophic magnification and isomer fractionation of perfluoroalkyl substances in the food web of Taihu Lake, China. Environ Sci Technol. 48(4):2173–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez LA, MacFarlane JK, Tcaciuc AP, Gschwend PM 2009. Measurement of Freely Dissolved PAH Concentrations in Sediment Beds Using Passive Sampling with Low-Density Polyethylene Strips. Environ Sci Technol. 43(5):1430–1436. doi: 10.1021/es802288w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman CL, Lohmann R 2014. Comparing sediment equilibrium partitioning and passive sampling techniques to estimate benthic biota PCDD/F concentrations in Newark Bay, New Jersey (U.S.A.). Environ Pollut. 186:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.12.002. [accessed 2016 May 31]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749113006246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh U, Kane Driscoll S, Burgess RM, Jonker MTO, Reible D, Gobas F, Choi Y, Apitz SE, Maruya KA, Gala WR, et al. 2014. Passive sampling methods for contaminated sediments: Practical guidance for selection, calibration, and implementation. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 10(2):210–223. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobas FAPC, de Wolf W, Burkhard LP, Verbruggen E, Plotzke K 2009. Revisiting bioaccumulation criteria for POPs and PBT assessments. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 5(4):624–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwend PM, MacFarlane JK, Reible DD, Lu X, Hawthorne SB, Nakles DV, Thompson T 2011. Comparison of polymeric samplers for accurately assessing PCBs in pore waters. Environ Toxicol Chem. 30(6):1288–1296. doi: 10.1002/etc.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson Ö, Haghseta F, Chan C, MacFarlane J, Gschwend PM 1997. Quantification of the Dilute Sedimentary Soot Phase: Implications for PAH Speciation and Bioavailability. Environ Sci Technol. 31(1):203–209. doi: 10.1021/es960317s. [accessed 2016 Mar 4]. 10.1021/es960317s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CP, Luthy RG 2007. Modeling Sorption of Anionic Surfactants onto Sediment Materials: An a priori Approach for Perfluoroalkyl Surfactants and Linear Alkylbenzene Sulfonates. Environ Sci Technol. 41(9):3254–3261. doi: 10.1021/es062449j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Khim JS, Wang T, Naile JE, Park J, Kwon B-O, Song SJ, Ryu J, Codling G, Jones PD, et al. 2015. Bioaccumulation characteristics of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in coastal organisms from the west coast of South Korea. Chemosphere. 129:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Dai J, Xu Z, Luo X, Cao H, Wang J, Mai B, Xu M 2010. Bioaccumulation behavior of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in the freshwater food chain of Baiyangdian Lake, North China. Environ Int. 36(4):309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke A, MacLeod M, Wickström H, Mayer P 2014. Equilibrium Sampling to Determine the Thermodynamic Potential for Bioaccumulation of Persistent Organic Pollutants from Sediment. Environ Sci Technol. 48(19):11352–11359. doi: 10.1021/es503336w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Ikonomou MG, Blair JD, Surridge B, Hoover D, Grace R, Gobas FAPC. 2009. Perfluoroalkyl contaminants in an Arctic marine food web: trophic magnification and wildlife exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 43(11):4037–4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key BD, Howell RD, Criddle CS 1997. Fluorinated Organics in the Biosphere. Environ Sci Technol. 31(9):2445–2454. doi: 10.1021/es961007c. [accessed 2016 Jun 13]. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es961007c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy MA, Barrett K, Lohmann R 2015. The changing sources of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and furans in sediments from the lower Passaic River and Newark Bay, New Jersey, USA. Environ Toxicol Chem. 35(3):in review. doi: 10.1002/etc.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy MA, Lohmann R 2017. Using Polyethylene Passive Samplers to Study the Partitioning and Fluxes of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in an Urban River. Environ Sci Technol. 51(16). doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy MA, Weinstein MP, Lohmann R 2014. Trophodynamic behavior of hydrophobic organic contaminants in the aquatic food web of a tidal river. Environ Sci Technol. 48(21). doi: 10.1021/es502886n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwadijk CJAF, Korytár P, Koelmans AA 2010. Distribution of Perfluorinated Compounds in Aquatic Systems in The Netherlands. Environ Sci Technol. 44(10):3746–3751. doi: 10.1021/es100485e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labadie P, Chevreuil M 2011. Partitioning behaviour of perfluorinated alkyl contaminants between water, sediment and fish in the Orge River (nearby Paris, France). Environ Pollut. 159(2):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, Lai D, Pfahles-Hutchens A, Seed J 2007. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicol Sci. 99(2):366–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann R 2012. Critical Review of Low-Density Polyethylene’s Partitioning and Diffusion Coefficients for Trace Organic Contaminants and Implications for Its Use As a Passive Sampler. Environ Sci Technol. 46:606–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann R, MacFarlane JK, Gschwend PM 2005. Importance of Black Carbon to Sorption of Native PAHs, PCBs, and PCDDs in Boston and New York Harbor Sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 39(1):141–148. doi: 10.1021/es049424+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi EIH, Yeung LWY, Taniyasu S, Lam PKS, Kannan K, Yamashita N 2011. Trophic magnification of poly-and perfluorinated compounds in a subtropical food web. Environ Sci Technol. 45(13):5506–5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker U, MacLeod M, Scheringer M, Hungerbühler K 2005. Improving Data Quality for Environmental Fate Models: A Least-Squares Adjustment Procedure for Harmonizing Physicochemical Properties of Organic Compounds. Environ Sci Technol. 39(21):8434–8441. doi: 10.1021/es0502526. [accessed 2016 May 5]. 10.1021/es0502526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach RP, Gschwend PM, Imboden DM 2005. Environmental Organic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons; [accessed 2016 May 30]. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=77ShpUHTZCYC&pgis=1. [Google Scholar]

- Shoeib M, Vlahos P, Harner T, Peters A, Graustein M, Narayan J 2010. Survey of polyfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) in the atmosphere over the northeast Atlantic Ocean. Atmos Environ. 44(24):2887–2893. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.04.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streets SS, Henderson SA, Stoner AD, Carlson DL, Simcik MF, Swackhamer DL 2006. Partitioning and Bioaccumulation of PBDEs and PCBs in Lake Michigan †. Environ Sci Technol. 40(23):7263–7269. doi: 10.1021/es061337p. [accessed 2016 Jun 13]. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es061337p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Toro DM, Zarba CS, Hansen DJ, Berry WJ, Swartz RC, Cowan CE, Pavlou SP, Allen HE, Thomas NA, Paquin PR 1991. Technical basis for establishing sediment quality criteria for nonionic organic chemicals using equilibrium partitioning. Environ Toxicol Chem. 10(12):1541–1583. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620101203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US EPA 1992a. National study of chemical residues in fish: volume I. doi:EPA 823-R-92–008a. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA 1992b. National study of chemical residues in fish: volume II. doi:EPA 823-R-92–008b. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA 2016a. Drinking water health advisory for PFOA and PFOS. :103. doi:EPA 822-R-16–005. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA 2016b. Estimation Programs Interface Suite™ for Microsoft® Windows, v 4.11.

- Wang D-Q, Yu Y-X, Zhang X-Y, Zhang S-H, Pang Y-P, Zhang X-L, Yu Z-Q, Wu M-H, Fu J-M 2012. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and organochlorine pesticides in fish from Taihu Lake: Their levels, sources, and biomagnification. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 82:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, MacLeod M, Cousins IT, Scheringer M, Hungerbühler K 2011. Using COSMOtherm to predict physicochemical properties of poly- and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs). Environ Chem. 8(4):389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Wirgin I, Roy NK, Loftus M, Chambers RC, Franks DG, Hahn ME 2011. Mechanistic Basis of Resistance to PCBs in Atlantic Tomcod from the Hudson River. Science (80- ). 331(6022):1322 LP–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J-P, Luo X-J, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Chen S-J, Mai B-X, Yang Z-Y 2008. Bioaccumulation of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in wild aquatic species from an electronic waste (e-waste) recycling site in South China. Environ Int. 34(8):1109–13. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.04.001. [accessed 2016 Jun 2]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412008000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia GS 1998. Sorption behavior of nonpolar organic chemicals on natural sorbents (PhD dissertation). John Hopkins University, Baltimore MD: John Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Guo C-S, Zhang Y, Meng W 2014. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of perfluorinated compounds in a eutrophic freshwater food web. Environ Pollut. 184:254–61. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.09.011. [accessed 2016 Apr 25]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S026974911300482X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Landrum PF, Lydy MJ 2006. Comparison of Chemical Approaches for Assessing Bioavailability of Sediment-Associated Contaminants. Environ Sci Technol. 40(20):6348–6353. doi: 10.1021/es060830y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WM, South P, Begley TH, Noonan GO 2013. Determination of Perfluorochemicals in Fish and Shellfish Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 61(46):11166–11172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.