Abstract

Objectives

Escherichia coli sequence types (STs) 69, 73, 95, 127, and 131 are major STs frequently causing extraintestinal infections. The prevalence of specific clones and their virulence and resistance profiles has not been described from Iran. The aim of this study was to characterize antimicrobial-susceptibility profiles and virulence traits of five major clones of E. coli recovered from human extraintestinal infections in Semnan, Iran. We compared these traits between major ST clones and also between O25b and O16 subgroups of the ST131 clone.

Methods

We characterized the five major ST clones among 335 collected E. coli isolates obtained from extraintestinal infections, and phylogenetic groups, antimicrobial susceptibility, and virulence/resistance-gene profiles of these major STs were studied.

Results

The highest rates of the multidrug-resistance phenotype were detected among ST131 (85.7%) and ST69 (41.7%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance was detected significantly among the latter clone. Of the 151 isolates belonging to major ST clones, blaOXA-48 was detected among all except the ST127 clone, while blaNDM genes were harbored by 14 (9.2%) isolates, which all belonged to the ST131 clone. Aggregate virulence scores (median) of ST131 isolates (11) were slightly higher than ST69 (8.50) strains, but were lower than ST73 (16), ST95 (16), and ST127 (12.50) isolates. Principal-coordinate analysis revealed distinct virulence profiles with the ST131 clone. ST73, ST95 and ST131 were enriched with “urovirulence” traits, including phylogroup B2 and group B2-associated accessory traits (chuA, iutA, yfcV, papGII, usp, kpsMTII and malX) and the derived variables extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli and uropathogenic E. coli. In contrast, ST69 was depleted of these traits, but enriched with phylogroups D and E.

Conclusion

Our data emphasize that isolates of the ST131 clone have the ability to make a balance between resistance and virulence traits to establish a wider clone in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli.

Keywords: ST131, carbapenem, PCoA, phylogroup, ExPEC, UPEC

Introduction

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) isolates cause various infections with considerable morbidity and mortality. This fraction of E. coli isolates is the most common cause of urinary tract infections, both in the community and health-care centers.1–3 The majority of these infections are caused by strains possessing the ability for colonization and survival in a specific niche and expressing an arsenal of virulence determinants.4,5 Treatment options are limited, due to the rise in prevalence of antibiotic-resistant strains.

Molecular epidemiology techniques, eg, multilocus sequence typing, are widely used to study ExPEC lineages, and sequence types (STs) 69, 73, 95, and 131 have been reported as pandemic clones among ExPEC isolates recovered from human infections.6–9 In a UK study, consistent prevalence of these four STs among ExPEC isolates from urinary and bloodstream infections has been shown. Collectively, they comprised 45% of the ExPEC strains from community and hospital urine samples recovered in 2007–2009 and 2007–2008 in North West England and the East Midlands, respectively, as well as 58% of those from bacteremia in northern England in 2010–2012.10 In contrast, there is no published report about the prevalence or phenotypic and genetic traits of these major STs among E. coli clinical isolates from Iran.

Identification of and distinguishing the major STs by rapid diagnostic tests could thus be helpful to select appropriate therapy before conventional susceptibility-test data become available. Despite the multilocus sequence-typing technique, which is a time-consuming and expensive method, simpler molecular strategies like the multiplex PCR designed and validated by Doumith et al might make testing more accessible to diagnostic laboratories.10 In this study, we used multiplex PCR to study the prevalence of the five major STs – ST69, ST73, ST95, ST127, and ST131 – among a collection of clinical E. coli isolates recovered from patients admitted to Kosar University Hospital in Semnan, Iran during a 1-year surveillance study. We also determined virulence/resistance-gene profiles and antibiotic-susceptibility patterns of these major pandemic clones, focusing especially on ST131 subclones.

Methods

Strains

The study was conducted at Kosar University Hospital which serves patients in Semnan (Iran) and provides medical and surgical care in all medical specialties. A total of 335 E. coli isolates were obtained from different wards of the hospital from March 2015 to March 2016. Isolates were recovered from different extraintestinal clinical specimens, including, urine, blood, wound, and respiratory samples. Medical records were reviewed to obtain demographic and clinical data. Samples were cultured on MacConkey agar and after an overnight 37°C incubation period, and single colonies with morphological Gram-negative characteristics were subjected to standard laboratory procedures guidelines. E. coli isolates were identified as lactose-fermenting, citrate- and urease-negative and indole-positive. A total of 335 nonduplicate clinical isolates of E. coli from 335 patients admitted to the hospital were taken for this study. Isolates were taken as part of routine hospital procedure; therefore patient consent was not required. This study was approved by Semnan University of Medical Sciences with the ethics codes IR.SEMUMS.REC.1395.19 and IR.SEMUMS.REC.1395.18.

Phylogrouping and sequence-typing PCR

DNA templates were extracted for PCR by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide.11 Major E. coli phylogroups (A, B1, B2, C, D, E, and F) were determined by multiplex PCR.12 The major ExPEC STs (ST131, ST95, ST73, ST69, and ST127) were identified as described previously.10 Moreover, E. coli isolates belonging to phylogroups B2, D, and F were subjected to a second gyrB–mdh multiplex PCR to screen for the detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in mdh and gyrB associated with the ST131 clone. The H30 and H30-Rx subclones of ST131 isolates were detected, and the two most common O types, O25b and O16, were screened by PCR among study ST131 isolates.13

Antimicrobial-susceptibility testing

Antibiotic-susceptibility profiles were obtained for all E. coli isolates using the standard disk-diffusion method on Mueller– Hinton agar. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) recommendations for antimicrobial-susceptibility testing were followed.14 Isolates with intermediate susceptibility patterns were categorized as resistant. Carbapenem-resistant isolates were those isolates with an inhibition zone of <23 mm to any of imipenem, meropenem, or ertapenem.14 The resistance score was the number of antibiotics to which an isolate was resistant.15 Multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates were those resistant to at least one representative of three or more antimicrobial classes.15 Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing isolates were detected by phenotypic combined-disk testing according to the recommendations of the CLSI.14

Detection of resistance genes

Isolates harboring resistance determinants, including carbapenemases (blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaIMP-, blaVIM-, and blaKPC),13 ESBLs (blaTEM-, blaSHV-, and blaCTX-M groups 1, 2, 8, 9, and 25), and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac6Ib-cr) were detected by multiplex PCR according to previously published methods.13 Moreover, isolates were screened for the presence of 16S rRNA methylase genes (armA, rmtB, and rmtC) and aminoglycoside-resistance determinants, including aac6-Ib/aac3-IIa genes.16 As positive controls, previously characterized isolates carrying resistance genes were used in this study.

Virulence-factor determination

The presence of 28 putative virulence genes was assessed by multiplex PCR.15 Isolates carrying two or more of the five markers, including afaDrBC, papAH, and/or papC, sfa, kpsM II, or iutA were presumed ExPEC, and isolates that tested positive for three or more of the four genes chuA, fyuA, vat, and yfcV were considered uropathogenic E. coli UPEC, as described previously.17 The number of unique virulence factors (VFs) detected for each isolate, counting the PAI marker as one, was considered the aggregate VF score.17

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test and the Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare proportions and scores, respectively. Principal-coordinate analysis, a multidimensional scaling method analogous to principal-component analysis, was used to collapse the molecular data set for simplified between-group comparisons.18 Groups were compared on each of the first three coordinates, which captured most of the variance within the data set, using a two-tailed t-test.

Results

Detection of major STs

With multiplex PCR, five major STs were detected among 151 (45%) of collected E. coli isolates. These isolates are detailed in Table 1. Compared with the other four STs, ST131 isolates were significantly associated with older patients (mean and median 69.17 and 74.1 vs 60.4 and 64.5, P<0.05). The five major STs were distributed similarly by specimen types and sex.

Table 1.

Distribution of major sequence types (STs) among clinical isolates

| Sex | n (%) | Age (mean, median), years | Sample, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Respiratory | Wound | ||||

|

ST69 (24) ST73 (13) |

Female | 14 (58.3) | 59.2, 64.5 | 18 (75) | 4 (16.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| Male | 10 (41.7) | |||||

| Female | 11 (84.6) | 62.3, 65 | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 0 | |

| Male | 2 (15.4) | |||||

| ST95 (15) | Female | 11 (73.3) | 57.3, 63 | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Male | 4 (26.7) | |||||

| ST127 (22) | Female | 11 (50) | 62.5, 68.5 | 19 (86.4) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) |

| Male | 11 (50) | |||||

| ST131 (77) | Female | 44 (57.1) | 69.1, 74.5 | 65 (84.4) | 8 (10.4) | 4 (5.2) |

| Male | 33 (42.8) | |||||

Relationships among phylogroups and major STs

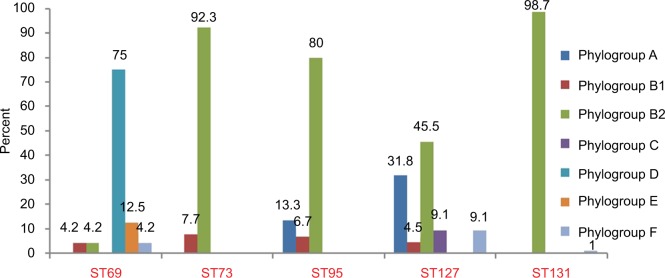

The phylogroups of the studied isolates are detailed in Figure 1. ST73 and ST95 were detected in phylogroups B1/B2 and A/B1/B2, while ST69 and ST127 were detected among all phylogroups, except A/C and D/E.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of five major sequence types (STs) among seven phylogroups.

Relationship between antimicrobial resistance and STs

Antimicrobial-resistance rates obtained for five major STs are represented in Table 2. Overall, 14 (9.2%) of 151 isolates (including seven ST95, five ST127, and one for each of ST69 and ST73) remained susceptible to all antimicrobials tested. Except for imipenem and meropenem, ST131 isolates showed higher rates of resistance compared to the other four major STs, exhibiting high prevalence (>85%) of resistance to aztreonam, fluoroquinolones, and cefotaxime, as well as MDR phenotype.

Table 2.

Overall prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among five major sequence types (STs)

| ST69 | ST73 | ST95 | ST127 | ST131 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Insusceptible isolates, n (%) | ||||

| Imipenem | 0 | 2 (15.4) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (2.6) |

| Meropenem | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Ertapenem | 0 | 3 (23.1) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (4.5) | 10 (13) |

| Ceftazidime | 8 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (18.2) | 59 (76.6) |

| P-valuea | 0.008 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | |

| Cefepime | 2 (8.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 4 (18.2) | 45 (58.4) |

| P-value | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cefotaxime | 9 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (46.7) | 10 (45.5) | 71 (92.2) |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | ||

| Aztreonam | 9 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 6 (27.3) | 68 (88.3) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Amoxicillin–clavulanate | 12 (50) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (26.7) | 11 (50) | 46 (59.7) |

| P-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | |||

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 1 (4.2) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (20) | 2 (9.1) | 13 (16.9) |

| Ampicillin–sulbactam | 2 (8.3) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (20) | 5 (22.7) | 34 (44.2) |

| P-value | 0.004 | 0.002 | |||

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | 22 (91.7) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (33.3) | 8 (36.4) | 53 (68.8) |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.008 | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | 5 (20.8) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (22.7) | 69 (89.6) |

| P-value | 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Levofloxacin | 2 (8.3) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (20) | 4 (18.2) | 68 (88.3) |

| P-value | 0.0001 | 0.007 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Amikacin | 2 (8.3) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 8 (10.4) |

| Gentamicin | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (9.1) | 34 (44.2) |

| P-value | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | ||

| Tobramycin | 3 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 3 (13.6) | 36 (46.8) |

| P-value | 0.006 | 0.0001 | |||

| MDR | 10 (41.7) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (22.7) | 66 (85.7) |

| P-value | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| Resistance score (mean, median) | 3.17, 2.50 | 3.54, 4 | 3, 1 | 2.77, 2 | 7, 7 |

| ESBL phenotype | 9 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (46.7) | 10 (45.5) | 71 (92.2) |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | ||

Notes:

Comparison between each ST with all other STs combined. Bold values indicate significant associations. P-values in rows shown for differences that were statistically significant (P<0.05). Underlining indicates a negative association.

Abbreviations: MDR, multidrug resistance; ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase.

Among the non-ST131 isolates, ST69 was characterized by a prevalence of 50% resistance to amoxicillin–clavulanate as well as a high rate (41.7%) of MDR phenotypes and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole resistance (91.7%), which were the highest rates among the four major STs. The highest aggregate resistance score was detected in the ST131 clone (median 7), and decreased progressively through ST73, ST69, ST127, and ST95 (medians, 4, 2.50, 2, and 1, respectively).

Relationship between resistance genes and STs

The frequency of resistance determinants among the five major STs is shown in Table 3. Of the 88 ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, 60 (68.2%) harbored aac6Ib-cr (P=0.004). While the prevalence of aac6Ib/aac3IIa genes among ST127 isolates was higher than other STs, the differences were borderline (P=0.06 for both genes) and not significant. Furthermore, resistance to gentamicin and tobramycin was significantly associated with the prevalence of aac3IIa, aac6Ib, aac6Ib-cr, and armA (P<0.05 for all). While the carbapenemase genes blaOXA-48 and blaNDM were found mostly among ST131 isolates (P<0.05), higher ertapenem resistance in this clone compared to other STs did not reach statistical significance. The prevalence rates of armA, qnrB, qnrS, blaTEM, CTX-M-G2, and CTX-M-G9 were higher among 74 non-ST131 isolates, reaching statistical significance for the latter resistance-gene cluster (P=0.002).

Table 3.

Prevalence of resistance determinants among different sequence types (STs)

| ST69 | ST73 | ST95 | ST127 | ST131 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance genes | Positive isolates, n (%) | ||||

| blaOXA-48 | 3 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 25 (32.5) |

| P-valuea | 0.008 | 0.001 | |||

| blaNDM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (18.2) |

| P-value | 0.001 | ||||

| blaTEM | 20 (83.3) | 6 (46.2) | 8 (53.3) | 16 (72.7) | 51 (66.2) |

| blaSHV | 8 (33.3) | 5 (38.5) | 7 (46.7) | 7 (33.3) | 35 (46.1) |

| qnrB | 7 (29.2) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (20) | 2 (9.1) | 15 (19.5) |

| qnrS | 11 (45.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (13.6) | 9 (11.7) |

| P-value | 0.0001 | ||||

| aac6Ib-cr | 9 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (53.3) | 16 (72.7) | 50 (64.9) |

| P-value | 0.04 | ||||

| aac6Ib | 8 (33.3) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (20) | 16 (72.7) | 48 (62.3) |

| P-value | 0.045 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| aac3IIa | 9 (37.5) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (40) | 16 (72.7) | 47 (61) |

| P-value | 0.03 | ||||

| armA | 5 (20.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (9.1) | 5 (6.5) |

| P-value | 0.05 | ||||

| CTX-M-G1 | 19 (79.2) | 6 (46.2) | 12 (80) | 17 (77.3) | 64 (83.1) |

| P-value | 0.008 | ||||

| CTX-M-G2 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| CTX-M-G8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (13.6) | 6 (7.8) |

| CTX-M-G9 | 14 (58.3) | 6 (46.3) | 9 (60) | 11 (50) | 22 (28.6) |

| P-value | 0.002 | ||||

| CTX-M-G25 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 24 (31.2) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | ||

Notes:

P-values shown for differences that were statistically significant (P<0.05). Bold values indicate significant associations (P≤0.05); underlining indicates negative associations.

Relationships among STs and virulence factors

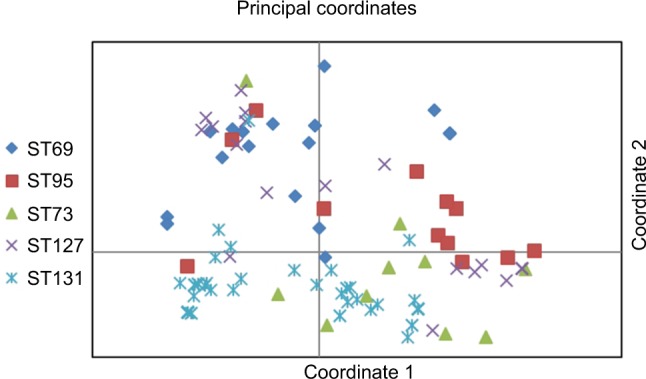

Based on the first two coordinates of a principal-coordinate analysis based on 28 studied virulence determinants, the virulence profiles of ST131 strains were highly distinctive, which significantly differentiated these isolates from other major ST isolates, whether these were considered collectively (P<0.001, one coordinate only) or by individual subset (P<0.001 for two or three coordinates per comparison). When the coordinate 1–coordinate 2 plane was plotted, variance of 45.5% was captured and the ST131 isolates clustered tightly in the lower half, which separated them from the other isolates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Principal coordinate–analysis plot for 151 Escherichia coli isolates belonging to five major sequence types (STs).

Notes: Principal-coordinate analysis based on 28 virulence genes. Coordinate 1 and 2 captured 25.5% and 20% of variance in the data set, respectively (total 45%).

With univariate analysis, aggregate virulence-profile differences were explored for individual virulence genes. Nine virulence genes were significantly more prevalent among ST131 isolates, while eleven virulence genes were detected significantly among the non-ST131 isolates (Table 4). ST131 isolates showed lower aggregate virulence scores (median) than ST73, ST95 (significantly), and ST127 (insignificantly), and were only slightly higher than among ST69 isolates (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence of 28 virulence genes among different sequence types (STs)

| ST69 | ST73 | ST95 | ST127 | ST131 | ST131 vs other STs (%) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive isolates, n (%) | |||||||

| Adhesions | |||||||

| afaDraBC | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 3 (13.6) | 12 (15.6) | 5.4 vs 15.6 | |

| papA | 10 (41.7) | 4 (30.8) | 11 (73.3) | 11 (50) | 29 (37.7) | 37.7 vs 48.6 | |

| papC | 16 (66.7) | 7 (53.8) | 13 (86.7) | 16 (72.7) | 33 (42.9) | 42.9 vs 70.3 | 0.001 |

| papEF | 12 (50) | 5 (58.5) | 11 (73.3) | 15 (68.2) | 29 (37.7) | 37.7 vs 58.1 | 0.01 |

| F10papA | 5 (20.8) | 7 (53.8) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (14.3) | 74 (96.1) | 96.1 vs 21.9 | 0.0001 |

| papG II | 10 (41.7) | 4 (30.8) | 10 (66.7) | 2 (9.1) | 31 (40.3) | 40.3 vs 35.1 | |

| papG III | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 11 (50) | 0 | 0 vs 17.6 | 0.0001 |

| sfafocDE | 1 (4.2) | 12 (92.3) | 3 (20) | 10 (45.5) | 0 | 0 vs 35.1 | 0.0001 |

| yfcV | 1 (4.2) | 12 (92.3) | 13 (86.7) | 13 (59.1) | 76 (98.7) | 98.7 vs 52.7 | 0.0001 |

| Toxins | |||||||

| hlyF | 4 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.3) | 1.3 vs 19.2 | 0.0001 |

| hlyA | 7 (29.2) | 10 (76.9) | 4 (26.7) | 11 (50) | 21 (27.3) | 27.3 vs 43.2 | 0.04 |

| vat | 0 | 12 (92.3) | 12 (80) | 11 (50) | 0 | 0 vs 47.3 | 0.0001 |

| cnf1 | 0 | 11 (84.6) | 1 (6.7) | 11 (50) | 20 (26) | 26 vs 31.1 | |

| sat | 6 (25) | 6 (46.2) | 3 (20) | 5 (22.7) | 72 (93.5) | 93.5 vs 27 | 0.0001 |

| cdtB | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 vs 2.7 | |

| Capsules | |||||||

| kpsMT II | 10 (41.7) | 12 (92.3) | 11 (73.2) | 13 (59.1) | 38 (49.4) | 49.4 vs 62.2 | |

| kpsMT K5 | 10 (41.7) | 11 (84.6) | 1 (6.7) | 11 (50) | 38 (49.4) | 49.4 vs 44.6 | |

| neuC | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 8 (53.3) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 vs 13.5 | 0.0001 |

| Siderophores | |||||||

| iutA | 10 (41.7) | 7 (53.8) | 12 (80) | 13 (59.1) | 71 (92.2) | 92.2 vs 56.8 | 0.0001 |

| iroN | 9 (37.5) | 13 (100) | 9 (60) | 10 (45.5) | 2 (2.6) | 2.6 vs 55.4 | 0.0001 |

| chuA | 23 (95.8) | 12 (92.3) | 12 (80) | 13 (59.1) | 76 (98.7) | 98.7 vs 81.1 | 0.0001 |

| fyuA | 21 (87.5) | 11 (84.6) | 13 (86.7) | 18 (81.8) | 76 (98.7) | 98.7 vs 85.1 | 0.0001 |

| Miscellaneous | |||||||

| ibeA | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 vs 1.4 | |

| usp | 0 | 12 (92.3) | 11 (73.3) | 11 (50) | 76 (98.7) | 98.7 vs 45.9 | 0.0001 |

| PAI | 0 | 12 (92.3) | 13 (86.7) | 13 (59.1) | 73 (94.8) | 94.8 vs 51.4 | 0.0001 |

| traT | 23 (95.8) | 5 (38.5) | 12 (80) | 18 (81.8) | 72 (93.5) | 93.5 vs 78.4 | 0.0009 |

| Protections | |||||||

| ompT | 4 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.3) | 1.3 vs 19.2 | 0.0001 |

| iss | 4 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1.3 vs 21.9 | 0.0001 |

| ExPEC | 13 (54.2) | 12 (92.3) | 15 (100) | 20 (90.9) | 70 (90.9) | 90.9 vs 81.1 | |

| UPEC | 1 (4.2) | 12 (92.3) | 13 (86.7) | 14 (63.6) | 76 (98.7) | 98.7 vs 54.1 | 0.0001 |

| VF score (mean, median, range) | 7.79, 8.50, 3–13 | 14.92, 16, 6–19 | 14, 16, 3–18 | 11.32, 12.50, 2–20 | 11.96, 11, 4–17 | 11 vs 11.50 | |

Notes:

Significant differences between ST131 and all other STs combined. Bold values indicate significant associations (P≤0.05); underlining indicates negative associations.

Abbreviations: ExPEC, extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli; UPEC, uropathogenic E. coli; VF, virulence factor.

The 28 virulence determinants tested were detected at least once, with the lowest rate of 0.7% (ibeA) to the highest rate of 92% (fyuA). Nearly 56% of the isolates were positive for the group II capsule-synthesis gene, with k5 accounting for 79.8% of the kpsM II-positive isolates. Overall, the five major STs were considerably different in VF content, from ST69 with the lowest VF score (mean 7.79, median 8.50), to ST73 with the highest VF score (mean 14.92, median 16). Despite the higher carriage rates of different pap genes among four major STs, ST131 isolates showed lower prevalence of these adhesion genes (mainly papC and papEF). A negative association was detected between the carriage of sfafocDE and iroN genes with ST131 isolates, while the sat gene was mostly harbored by this clone. Among the different STs, PAI, cnf1, and usp had negative associations with the ST69 clone (Table 4). Furthermore, the lowest rates of ExPEC and UPEC fractions among study isolates were found in this clone.

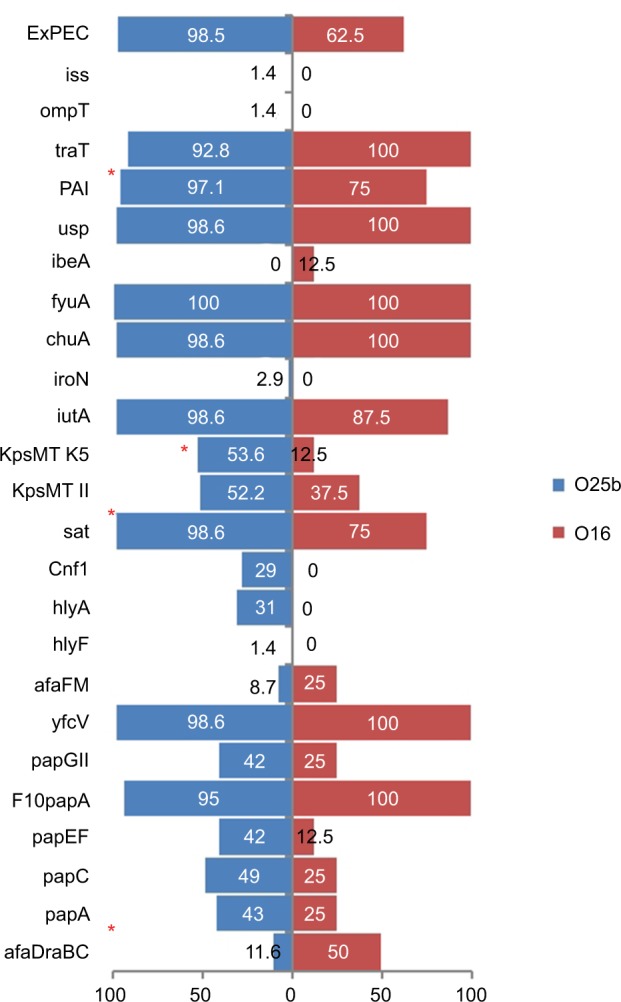

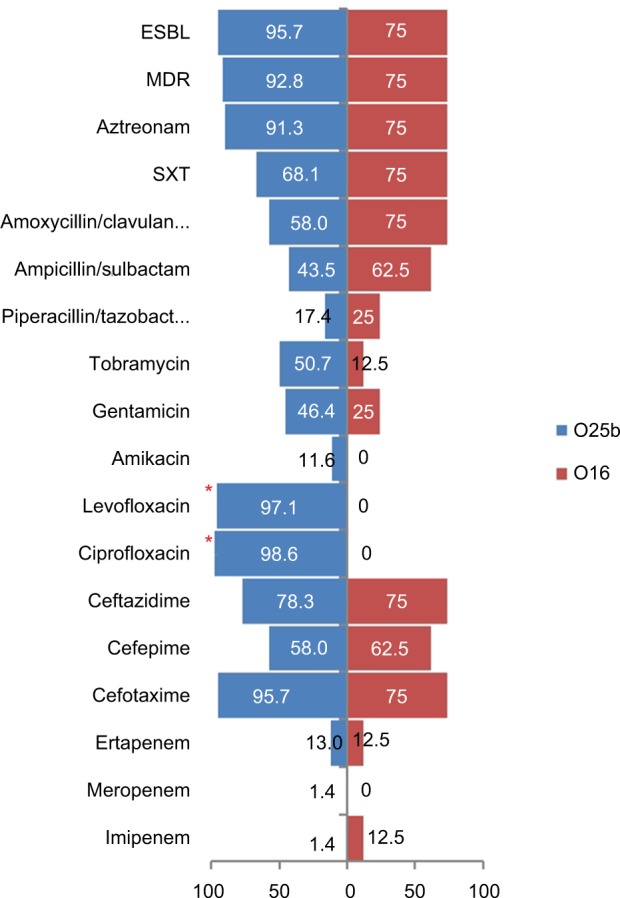

Eight of the 77 ST131 isolates belonged to the O16 subgroup and H30-negative and fluoroquinolone-susceptible, while the remaining 69 isolates were O25b- and H30-positive and fluoroquinolone-resistant, with a higher prevalence of ExPEC fraction compared to O16 (68 [98.5%] vs 5 [62.5%], P=0.003). The prevalence of four virulence genes – afaDrBC (eight [11.6%] vs four [50%], P<0.01), sat (68 [98.6%] vs six [75%], P=0.02), k5 (37 [53.6%] vs one [12.5%], P<0.05), and PAI (67 [97%] vs six [75%], P<0.05) – were significantly different between the O25b and O16 subgroups (Figure 3). Resistance rates of the O16 subgroup against imipenem, cefepime, amoxicillin–clavulanate, piperacillin–tazobactam, ampicillin–sulbactam, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole were higher than O25b, but were not statistically significant (Figure 4). The H30Rx subclone was detected in 31 (45.6%) of the 68 H30-positive isolates.

Figure 3.

Virulence genotypes of 77 ST131 Escherichia coli isolates based on O25b and O16 subgroups.

Note: *P≤0.05 between two subgroups.

Abbreviation: ExPEC, extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli.

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial-resistance rate (%) of 77 ST131 Escherichia coli isolates based on the O25b and O16 subgroups.

Note: *Significant difference (P<0.05).

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended spectrum β-lactamase; MDR, multidrug resistance; SXT, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.

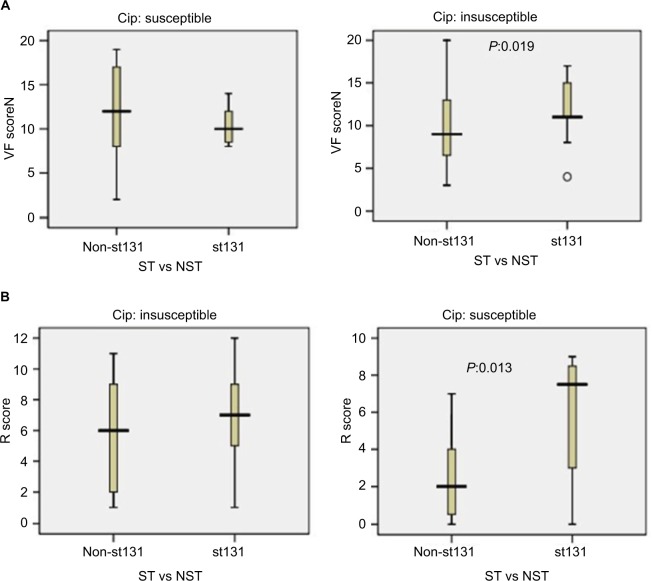

Relationship between ciprofloxacin resistance and virulence/resistance scores

Based on ciprofloxacin susceptibility, virulence and aggregate resistance scores were compared between ST131 and the other four major ST isolates. Among ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates, VF scores were high between ST131 and non-ST131 isolates (median ST131 vs non-ST131 10 vs 12, P=0.32). In contrast, among ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, the ST131 clone showed much higher VF scores (median 11) than non-ST131 isolates (median 9, P=0.019; Figure 5A). For aggregate resistance scores, a significant difference was detected between two groups of ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates (median ST131 vs non-ST131 7.50 vs 2, P=0.013); however, the difference did not reach statistical significance for ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates (median ST131 vs non-ST131 7 vs 6, P=0.064; Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Virulence and resistance among ST131 and non-ST131 Escherichia coli isolates within two ciprofloxacin-resistance groups.

Notes: Box-and-whisker plots show group medians (heavy horizontal bar) and maximum/minimum values (light horizontal bars). P-values determined by Mann–Whitney U test (two-tailed) shown for ST131 vs non-ST131 comparisons when P<0.05. (A) Virulence scores (number of distinct virulence genes) among ST131 vs non-ST131 isolates within each resistance group; (B) resistance (R) scores among ST131 isolates vs non-ST131 isolates within each resistance group.

Abbreviations: VF, virulence factor; ST, sequence type; NST, non-ST.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed 335 clinical E. coli isolates from extraintestinal specimens collected from patients admitted to Kosar University Hospital in Semnan, Iran during March 2015 to April 2016 for five major STs, phylogroup, and virulence/resistance genes, and compared these results with resistance phenotype, specimen type, and host age. To our knowledge, this is the first study to screen for major STs of E. coli within a set of systematically collected E. coli clinical isolates from Iran.

The antibiotic-resistant phenotypes seen here mirror more general patterns, with multiresistance, particularly to cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and gentamicin, mainly detected among the ST131 clone. In contrast, ST69 isolates were mostly resistant to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and showed the highest rate of MDR phenotypes among 74 non-ST131 isolates. Similarly, the majority of ST73, ST95, and ST127 isolates were susceptible or resistant to no more than two classes of antibiotics.

One of the major ST clones reported among UPEC isolates is ST73.19 Our data emphasize the increased virulence of this clone to humans. In fact, the highest virulence scores in our data were detected among ST73 (median 16), together with ST95. With one exception, ST73 isolates showed higher rates of VFs (mean, median, and range) compared to ST69 strains. The traT gene was mostly detected among ST69 isolates. This finding has been reported in previous surveys.20 The traT protein is responsible for development of a resistance phenotype against serum bactericidal activity, and may confer additional advantage to ST69 isolates. Despite the lowest rates of ExPEC and UPEC among studied ST69 isolates compared to other STs, the success of this clone can also be due to the presence of a higher rate of an MDR phenotype, especially to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, selected by the high prescription of this drug, freely available in Iranian pharmacies.

In comparison with ST69, the presence of PAI, usp, iroN, kpsmTII, k5, cnf1, vat, hlyA, yfcV, and sfa were significantly associated with ST73 (P<0.05 for all). In a large study of E. coli from food, animals, and humans conducted by Manges et al, ST73 exclusively was detected among isolates from humans, showing food sources are unlikely. As such, it seems that ST73 isolates are human pathogens, and their unnoticed circulation in gut microbiota increases the chance of different extraintestinal infections in those with predisposing conditions.21

The ST95 clone has been shown to be associated with avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC),22 and isolates of this clone are recovered mainly from food.23 Some of the reference strains, including UPEC strains UTI189 and NU14, and the neonatal meningitis strain RS218 are ST95,23 and in a recent study svg-gene carriage was used as a detection marker for identification of the ST95 clone among a group of APEC and ExPEC isolates.24 Our data showed the highest rate of ExPEC-positive isolates among this clone, and ST95 isolates were associated with the carriage of five genes (iutA, ompT, iss, hlyF, and iroN) which have been shown to correspond to APEC pathotypes.25 Similarly, ST95 showed the lowest resistance score and MDR phenotype, together with ST127, which emphasizes the inverse relationship between the prevalence of virulence genes and resistant phenotypes.

In our study, the broad range of VF genes screened revealed VF patterns were significantly associated with different STs. ST127, which has been reported to be the cause of pyelonephritis,26 showed lower rates of UPEC than ST73, ST95, and ST131 clones. However, ST127 isolates were associated with higher rates of some adhesions and toxins, especially papACEFGII, sfa, vat and cnf1, compared to other STs. Infections caused by isolates with such virulence potential may result in extensive exposure to antibiotics and increase the chances of acquisition of antibiotic-resistance determinants,19 as the highest rates of aac6Ib, aac6Ib-cr, and aac3IIa carriage, which mediate the low-level-resistance phenotype to aminoglycosides/fluoroquinolones were detected among this clonal lineage.

The basis for the O25b-ST131 serogroup’s impressive epidemiological success, which contrasts with the limited success of the O16 subclone, needs to be studied further. We found that among ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, despite the similar rates of MDR phenotype and ExPEC fraction between ST131 (all H30 subclones) and non-ST131 isolates, the ST131 clone showed more extensive virulence profiles. In contrast, among ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates, ST131 strains (all non-H30 and O16) had a major advantage over other STs for extent of resistance and comparably extensive virulence profiles and ExPEC fraction. As such, among ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, H30 and H30Rx subclones have multiple factors favoring their superiority over other ST clones. Among ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates, competition with other phylogroup B2 isolates may have limited O16-ST131 epidemiological success, and lower virulence determinants (although the difference was not significant in our study) are a determinant of this limitation.

Compared to the other four major STs, the study ST131 isolates showed distinctive virulence profiles that lacked some adhesions like fimbriae, but indicated significant reliance on nonfimbrial adhesions (afaDrBC). With some minor differences, study ST131 isolates were seen to harbor a collection of VFs similar to those reported from Spain,27 the UK,28 and US.18 It has been shown that the O25b subgroup has high virulence potential, which is corroborated here, but the number of O16 serogroups in our study isolates may have limited the ability to differentiate significantly between the O25b and O16 serogroups on the basis of virulence and multidrug resistance. Despite the lower number of O16-ST131 isolates, higher rates of resistance were detected against trimethoprim–sulfa-methoxazole, piperacillin–tazobactam, ampicillin–sulbactam, amoxicillin–clavulanate, and cefepime compared to the O25b serogroup. Therefore, it seems that ST131 clonal subsets exhibit distinctive associations with drug resistance, virulence contents, and host subsets, corroborating the importance of considering these subsets individually, rather than lumping them together as a single ST131 clone.15

Conclusion

We have described the virulence/antimicrobial resistance and phylogenetic diversity of ExPEC isolates, with particular reference to five major ST clones. ST127 has high adhesion potential, harbors plasmid-mediated aac genes, and warrants closer attention. The highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and virulence scores are linked to ST131, including its H30-predominant subgroup, and ST73. Coexpression of drug resistance and virulence among the ST131 clonal group along with widespread dissemination among locales underline its epidemiological superiority over other clones.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper would like to express their deepest gratitude to Professor James R Johnson, for his really valuable guidance in the principal-coordinate analysis of results. This work was supported fully by Semnan University of Medical Sciences (grants 1039 and 1040). This is a report of a database from research projects entitled “Detection of plasmid mediated quinolone resistance genes and CTX-M beta-lactamases among extra intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates recovered from hospitalized patients” and “Detection of aminoglycoside resistance genes among extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli isolates recovered from hospitalized patients”, registered at Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

Footnotes

Author contributions

ZH developed the concept and designed the experiments. ND and MA isolated bacteria and performed the laboratory measurements. MM collected and analyzed the epidemiological and clinical data and also the principal coordinate–analysis graph. OP wrote the paper. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Johnson JR, Russo TA. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: “the other bad E coli”. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;139(3):155–162. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.121550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo TA, Johnson JR. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(5):1753–1754. doi: 10.1086/315418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foxman B, Brown P. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: transmission and risk factors, incidence, and costs. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17(2):227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(2):273–2815. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coque TM, Novais Â, Carattoli A, et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):195–200. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams-Sapper S, Diep BA, Perdreau-Remington F, Riley LW. Clonal composition and community clustering of drug-susceptible and -resistant Escherichia coli isolates from bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(1):490–497. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01025-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee R, Johnston B, Lohse C, et al. The clonal distribution and diversity of extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates vary according to patient characteristics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57(12):5912–5917. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaureguy F, Landraud L, Passet V, et al. Phylogenetic and genomic diversity of human bacteremic Escherichia coli strains. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):560. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tartof SY, Solberg OD, Manges AR, Riley LW. Analysis of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(12):5860–5864. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.5860-5864.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doumith M, Day M, Ciesielczuk H, et al. rapid identification of major Escherichia coli sequence types causing urinary tract and bloodstream infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(1):160–166. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02562-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghotaslou R, Aghazadeh M, Ahangarzadeh Rezaee M, Moshafi MH, Forootanfar H, Hojabri Z. The prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes among coagulase negative staphylococci in Iranian pediatric patients. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:569–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E, Gordon DM. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5(1):58–65. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hojabri Z, Mirmohammadkhani M, Kamali F, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 and its H30/H30-Rx subclones recovered from extra-intestinal infections: first report of OXA-48 producing ST131 clone from Iran. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(10):1859–1866. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twentieth Informational Supplement M100-S23. USA: CLSI; 2013. Wayne, PA 19087. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JR, Porter S, Thuras P, Castanheira M. The pandemic H 30 sub-clone of sequence type 131 (ST131) as the leading cause of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli infections in the United States (2011–2012) Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(2):ofx089. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haldorsen BC, Simonsen GS, Sundsfjord A, Samuelsen O, Norwegian Study Group on Aminoglycoside Resistance Increased prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in Norway is associated with the acquisition of AAC(3)-II and AAC(6′)-Ib. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(1):66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nüesch-Inderbinen MT, Baschera M, Zurfluh K, et al. Clonal diversity, virulence potential and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli causing community acquired urinary tract infection in Switzerland. Front Microbiol. 2017;1(8):2334. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson JR, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Castanheira M. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(3):286–294. doi: 10.1086/653932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibreel TM, Dodgson AR, Cheesbrough J, et al. Population structure, virulence potential and antibiotic susceptibility of uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Northwest England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(2):346–356. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Souza da-Silva AP, de Sousa VS, Martins N, et al. Escherichia coli sequence type 73 as a cause of community acquired urinary tract infection in men and women in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manges AR, Harel J, Masson L, et al. Multilocus sequence typing and virulence gene profiles associated with Escherichia coli from human and animal sources. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12(4):302–310. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mora A, López C, Dabhi G, et al. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli O1:K1:H7/NM from human and avian origin: detection of clonal groups B2 ST95 and D ST59 with different host distribution. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9(1):132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent C, Boerlin P, Daignault D, et al. Food reservoir for Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(1):88–95. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.091118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson TJ, Wannemuehler Y, Johnson SJ, et al. Comparison of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains from human and avian sources reveals a mixed subset representing potential zoonotic pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(22):7043–7050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01395-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson TJ, Wannemuehler Y, Doetkott C, et al. Identification of minimal predictors of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli virulence for use as a rapid diagnostic tool. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(12):3987–3996. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00816-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brzuszkiewicz E, Brüggemann H, Liesegang H, et al. How to become a uropathogen: Comparative genomic analysis of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(34):12879–12884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coelho A, Mora A, Mamani R, et al. Spread of Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131 producing CTX-M-15 and SHV-12 with high virulence gene content in Barcelona (Spain) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(3):517–526. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croxall G, Hale J, Weston V, et al. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from a regional cohort of elderly patients highlights the prevalence of ST131 strains with increased antimicrobial resistance in both community and hospital care settings. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(11):2501–2508. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]