Abstract

Objective

To examine the evidence for the use of psychological and psychosocial interventions offered to forensic mental health inpatients.

Design

CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect and Web of Science databases were searched for research published in English between 1 January 1990 and 31 May 2018.

Outcome measures

Disturbance, mental well-being, quality of life, recovery, violence/risk, satisfaction, seclusion, symptoms, therapeutic relationship and ward environment. There were no limits on the length of follow-up.

Eligibility criteria

We included randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies of any psychological or psychosocial intervention in an inpatient forensic setting. Pilot or feasibility studies were included if an RCT design was used.

We restricted our search criteria to inpatients in low, medium and high secure units aged over 18. We focused on interventions considered applicable to most patients residing in forensic mental health settings.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers extracted data and assessed risk of bias.

Results

17 232 citations were identified with 195 full manuscripts examined in detail. Nine papers were included in the review. The heterogeneity of the identified studies meant that meta-analysis was inappropriate. The results were presented in table form together with a narrative synthesis. Only 7 out of 91 comparisons revealed statistically significant results with no consistent significant findings. The most frequently reported outcomes were violence/risk and symptoms. 61% of the violence/risk comparisons and 79% of the symptom comparisons reported improvements in the intervention groups compared with the control groups.

Conclusions

Current practice is based on limited evidence with no consistent significant findings. This review suggests psychoeducational and psychosocial interventions did not reduce violence/risk, but there is tentative support they may improve symptoms. More RCTs are required with: larger sample sizes, representative populations, standardised outcomes and control group interventions similar in treatment intensity to the intervention.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017067099.

Keywords: forensic, mental health, psychological, psychosocial, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first published review examining psychological or psychosocial interventions that could be accessed by the majority of forensic mental health inpatients.

Good quality randomised controlled trials are able to be undertaken in forensic settings to examine psychological and psychosocial interventions.

Current practice is based on limited evidence with no consistent findings.

Future large-scale trials are necessary to evaluate these interventions.

Introduction

Forensic mental healthcare is distinct from other psychiatric services.1 Patients in forensic mental health inpatient services are a complex group with a strong likelihood of presenting with multiple problems and a range of offending behaviours. These patients are generally subject to mental health or criminal justice legislation. Forensic mental health services tasked with the rehabilitation of this group of patients have additional roles to those of generic adult mental health services2 with a dual rehabilitative role, providing interventions to restore mental well-being while reducing the risk posed by individuals in preparation for discharge to conditions of lower security.3

The therapies used with forensic mental health patients are generally based on research with non-offending patients in general mental health settings. The majority of these are not empirically tested in forensic populations. Reviewers have questioned the appropriateness of transposing these treatments4 with interventions viewed as effective in non-forensic settings having little or no effect in forensic settings.5 This raises doubts about the efficacy of interventions used in a forensic mental health context.

Previous reviews of interventions in forensic units have focused on specific populations such as patients with personality disorder6 7 or sex offenders.8 9 However, there have been no published reviews examining psychological or psychosocial interventions that could be accessed by the majority of forensic mental health inpatients. Determining whether forensic interventions are effective is imperative to support the principle of evidence-based practice in forensic services. Randomised controlled trials are the preferred option for generating this evidence, and though acknowledging a controlled trial design is hard to achieve in a secure inpatient setting, other specialities have overcome these challenges.10 This review examines psychological and psychosocial interventions offered to forensic mental health inpatients. We focused on those interventions not specific to one offending type and so considered applicable to most patients residing in forensic mental health settings.

Methods

This systematic review followed a prespecified protocol and is reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Intervention and outcomes

We included all studies reporting the results of a psychological or psychosocial intervention. These were defined broadly. Psychological interventions refer to treatments based on a theory of psychological functioning while psychosocial interventions represent less specific interventions designed to improve mental health through general support, advice and encouragement.11 This includes psychoeducational strategies, cognitive–behavioural therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, non-directive counselling, supportive interactions and tangible assistance, through individual or group sessions.12 We were interested in 10 outcomes: disturbance, mental well-being, quality of life, recovery, violence/risk, satisfaction, seclusion, symptoms, therapeutic relationship and ward environment. The outcomes were based on the rated importance of outcome domains for forensic mental health research13 and the suitability of assessing these outcomes in forensic inpatient settings. There were no limits on the length of follow-up.

Study design

We only included randomised controlled trial studies. Pilot or feasibility studies were included if a randomised controlled trial design was used.

Data collection

The title and abstracts of studies identified through the search strategy were screened for eligibility by one reviewer using the inclusion criteria. The second reviewer independently screened a 20% random selection of the studies. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions between the two reviewers. Full-text articles were obtained for all studies meeting the initial eligibility criteria. All full-text articles were then examined independently by both reviewers to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the review. Reference lists of all relevant articles were also searched. A data extraction sheet was developed to enable assessment and synthesis of the included studies.

Registration details

We registered the protocol of our systematic review on 21 May 2017 on the PROSPERO database available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017067099.

Search strategy

The focus of the review was to examine psychological and psychological interventions in forensic mental health settings. CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect and Web of Science databases were searched. We searched for peer-reviewed articles, working papers and policy reports, published in English between 1 January 1990 and 31 May 2018. The following search terms were used:

psychiatr* OR mental*

AND

forensic OR secure OR disordered OR offender*

AND

psycholog* OR psychosocial* OR therap*

AND

quality OR wellbeing OR satisfaction OR recovery OR behavio* OR disturb* OR violen* OR seclusion OR abscond* OR symptom* OR environment OR atmosphere

AND

RCT OR random* OR control* OR placebo OR TAU.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included any psychological or psychosocial intervention given as an individual or group treatment in an inpatient forensic setting. We excluded interventions focusing specifically on a specific cohort (ie, sex offenders) as we were interested in examining approaches appropriate for the vast majority of inpatients in secure units.

We restricted our search criteria to forensic inpatients in low, medium and high secure units aged over 18 years. Our exclusion criteria included community settings where patients received treatment outside of the forensic unit or resided outside of the forensic unit when they were not receiving treatment. However, as detailed in the results section, we decided to include one study where a minority of the participants were residing in the community. We also excluded prison settings that are not deemed places of treatment under the Mental Health Act.

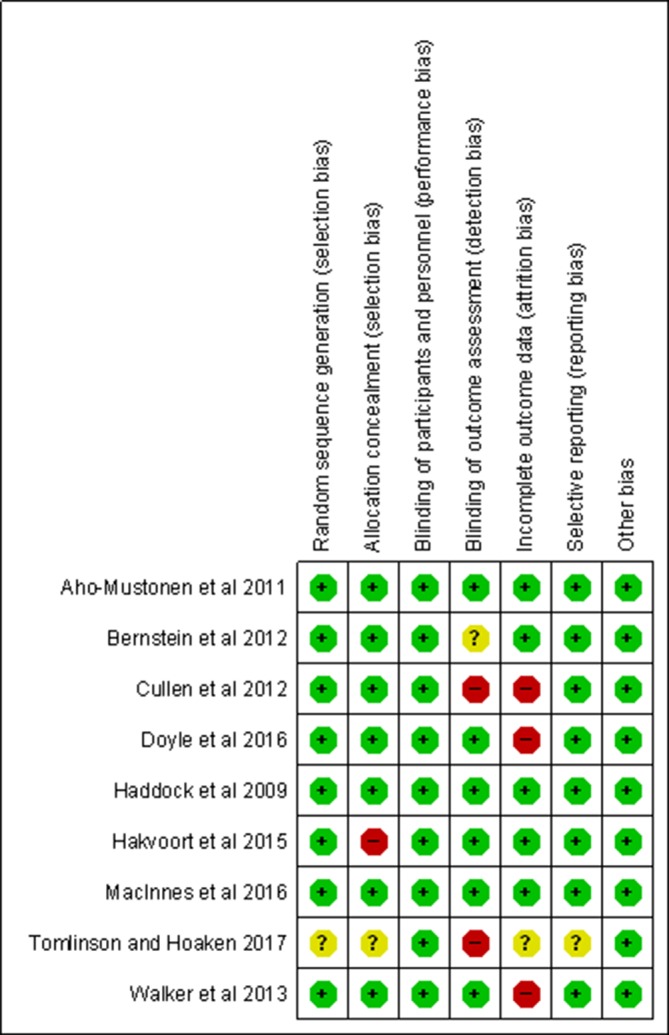

Risk of bias summary

We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool14 to evaluate six domains of bias: selection bias (random sequence of generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) and other bias. The risk of bias for each domain was rated as high (seriously weakens confidence in the results), low (unlikely to seriously alter the results) or unclear. The risk of bias assessment was conducted by the authors separately. There was an average of 1–2 domain ratings per study where there was an initial disagreement. In all cases, the reviewers discussed and agreed the ratings without involving a third party reviewer.

Data synthesis

Meta-analysis was initially planned but was considered inappropriate because of the heterogeneity of the identified studies due to: the different characteristics of the participant inpatient populations, the different types of approach used by the intervention and control groups and the different outcome measures being used. We therefore present the results in table form together with a narrative synthesis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or analysis of this review.

Results

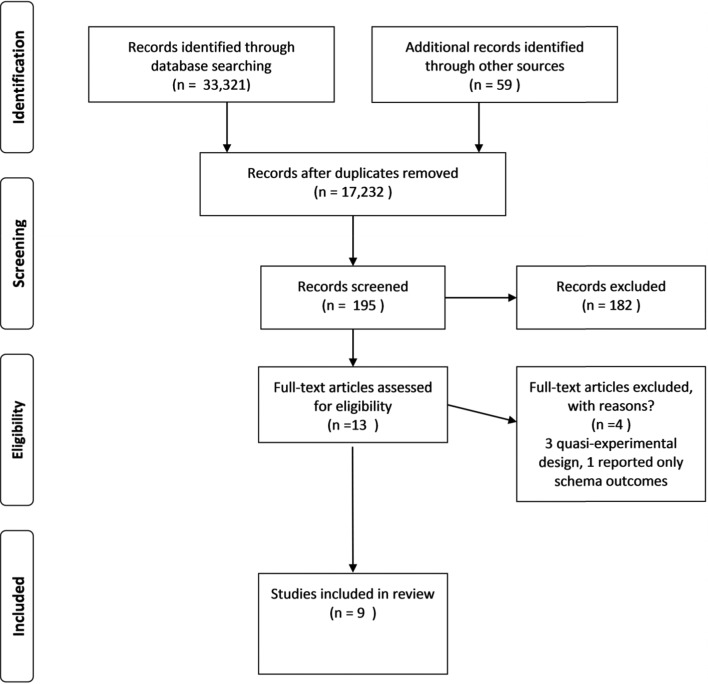

Our search of the five databases yielded 33 321 hits with 17 232 hits recorded once duplicates were removed. A flow chart detailing the screening process is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

The number of hits recorded for each database was:

CINAHL: 103.

MEDLINE: 11 951.

PsychInfo: 850.

ScienceDirect: 2189.

Web of Science: 18 228.

From this number, a total of 195 papers were selected to be examined in more detail for eligibility for inclusion in the review. Of these, 13 full-text papers were considered.15–27 The other 182 studies retrieved did not meet the inclusion criteria due to: the study not being a RCT, the study population not based in forensic inpatient settings, the intervention not psychological or psychosocially focused or a sex-offending intervention. From the 13 papers we considered in full, four were eventually excluded leaving nine papers chosen for inclusion in the review. Three papers were excluded because a quasiexperimental design was used.17 20 24 The fourth study was excluded as schema modes were the only outcomes reported.26

Study setting and characteristics

The trials’ characteristics are shown in table 1. The trials involved 523 participants with a median sample size of 63, ranging from 14 to 112. Five studies included women with a total of 37 participants accounting for 7.1% of the overall sample. All participants were individually randomised except for one study23 where cluster randomisation was used. Eight studies were conducted in the UK, two in the Netherlands, one in Finland and one in Canada. Four studies were conducted in high secure settings and three studies in medium secure settings. The other two studies were conducted in a combination of high, medium and low secure settings including one study where a minority of the participants were living in the community.21 Four of the studies included participants diagnosed with schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder, three studies included participants with a diagnosis of personality disorder and two studies included participants from both diagnostic groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors | Country | Setting | Inclusion criteria | Number | Withdraw/dropout | Intervention | Control | Other |

| Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Finland | High secure |

Schizophrenia and schizoaffective. | 39 total: 35 men, 4 women. |

1 Int. 2 TAU. ITT: unsure. |

Psychoeducation programme eight weekly sessions. Therapists: two psychologists who completed 2-day training programme. Fidelity reported. |

TAU. | |

| Bernstein et al 16 | The Netherlands | High secure | Personality disorder. | 35 All men. |

5 not sure which arm. ITT: yes. |

Three years of schema therapy usually delivered twice a week. Therapists completed 8-day training programme and 2× monthly supervision groups. Fidelity reported. |

TAU. Clinics free to choose. Typically a form of cognitive–behavioural, psychodynamic or humanistic psychotherapy. |

Part of a long-term study of 102 patients. |

| Cullen et al.18

Some outcomes reported in Cullen et al.40 |

UK | Medium secure |

Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder or other psychotic disorder; a history of violence; no prior participation in Reasoning and Rehabilitation (R&R) programme previously. | 84 All men. |

31 Int. 4 TAU. 23 out of 44 (52.3%) did not complete treatment. ITT: yes. |

R&R programme structured, manualised programme. Minimum of 36 2-hour sessions (2 or 3 per week). Therapists -experienced staff who received 3–5 days’ training from programme authors. Fidelity reported |

TAU. | Small sample size and low base rates of violent behaviour reducing likelihood of effect sizes. Randomisation occurred within sites and may have led to contamination across treatment. Possibility of bias as it was not possible to blind researchers to allocation status. 23% of referred patients refused to participate in the study. |

| Doyle et al.19

Some outcomes reported in Tarrier et al.41 |

UK | High secure | Personality disorder | 63 total. All men. |

At 36 months: 19 Int. 14 TAU. At 24 months 14 Int. ITT : yes. |

SFT. Weekly 1-hour sessions for at least 18 months. Therapists were two experienced cognitive therapists who received specialist SFT training with ongoing supervised practice and supervision. Fidelity reported – uncertain therapist competence. |

TAU. >14 reported. Group-based enhanced thinking skills and sex offender treatment were the most frequently provided therapies recorded on the TAU logs. |

Problems recruiting participants and refusing to be interviewed or filling in forms incorrectly (37 out of initial 136 patients considered – 29.4%). High attrition; poor statistical power; insufficient frequency of ST; and the provision of ST by only two therapists. |

| Haddock et al 21 | UK | High, medium and low secure 48 (62.3%). The other patients were living in the community. | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and history of violent behaviour. |

77 total: 66 men (85.7%), 11 women (14.3%). |

9 in total. Unclear regarding which groups. ITT: Yes. |

CBT. 25 sessions. Therapists experienced in CBT for people with psychosis, received training in the protocol and supervision. Fidelity assessed. |

Social activity therapy. 25 sessions. Fidelity assessed. |

108 of whom were identified as meeting initial inclusion criteria. Thirty-one refused to be assessed to determine eligibility (28.7%). |

| Hakvoort et al 22 | The Netherlands | High secure | Personality disorder. Addictions. No previous TBS admission. |

14 total. All men. |

2 ITT: unsure. |

Cognitive–behavioural music therapy and anger management 20×1 hours weekly sessions. Five therapists experienced in CBT music therapy in forensic psychiatry. Trained on a standard protocol. Fidelity assessed. |

TAU. Most also received anger management sessions. 3 hours per week. |

Six out of 21 identified refused to participate (28.6%). |

| MacInnes et al 23 | UK | Medium secure | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar, depression psychosis and personality disorder. | 112 total: 91 men (85%), 16 women (15%). Five data missing. |

Int: 7 (13%) 6 months. 8 (15%) 12 months. TAU: 15 (26%) 6 months. 15 (26%) 12 months. ITT: yes |

Computer-aided solution focused on brief therapy. 6×1 hour monthly session. Staff trained in SFBT techniques. Fidelity assessed. |

TAU. | Significantly more women withdrew from the study. |

| Tomlinson and Hoaken25 | Canada | Medium secure | Pts experiencing emotional dysregulation. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar, depression psychosis and personality disorder. |

18 total: 14 men (78%), 4 women (22%). |

Int: 3 (33%). TAU: 2 (22%). ITT: unsure. |

DBT skills training sessions provided weekly for 1.5 hours for 6 months (24 total sessions). Followed training manual. 1 hour weekly staff consultation groups. Fidelity not reported. |

TAU. | |

| Walker et al 27 | UK | High, medium and low secure. | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar, depression and psychosis. | 81 total: 79 men, 2 women. |

16. Int. 0 TAU. ITT: unsure. |

Psychoeducation programme. Two sessions per week for 11 weeks. Therapists: consultant psychiatrist and clinical nurse specialist. Fidelity not reported. |

TAU. No psychological interventions but able to attend social and occupational activities. |

Recruitment problems 26 out of 107 (24.3%) eligible participants not included. Recorded as not randomised. |

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; Int, Intervention; ITT, intention to treat; SFBT, solution-focused brief therapy; SFT, schema-focused therapy; TAU, treatment as usual.

Types of intervention

Five broad types of intervention were undertaken (cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), psychoeducation, schema-focused therapy (SFT) and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT)).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Three studies used this approach. The aim of cognitive/behavioural treatment programmes in forensic mental health settings is to change the criminogenic thinking of offenders.28

Cullen et al 18 based their intervention on the ‘Reasoning and Rehabilitation’ programme developed in Canada and sought to teach offenders a range of cognitive and behavioural skills.29

Haddock et al 21 used a manualised CBT programme including motivational strategies to aid engagement, strategies to reduce the severity and distress of psychotic symptoms and the severity of anger linked to aggression and violence.

Hakvoort et al 22 focused on cognitive–behavioural music therapy and focused on minimising risk and addressing the treatment needs of forensic psychiatric patients.

Dialectical behaviour therapy

One study by Tomlinson and Hoaken used this approach. DBT30 blends validation and acceptance strategies with change-focused CBT.20 The study focused on DBT skills training to reduce aggression.

Psychoeducation

This was the intervention in two studies. Education is offered to individuals with psychological disorders with interventions varying from the delivery of simple information through leaflets, emails or information websites to active multisession group intervention with therapist guidance and practice exercises.31

Aho-Mustonen et al 15 used a manualised psychoeducational programme.

Walker et al’s intervention27 was based on a training manual developed by the State Hospital, Carstairs, where the study was based.32

Schema-focused therapy

Two studies employed SFT. This integrated therapy was specifically developed for people with personality disorder combining CBT with attachment, gestalt, object relations, constructivist and psychoanalytic approaches.33

Bernstein et al 16 focused on the emotional states (‘schema modes’) most common in forensic patients with personality disorders that were hypothesised to play a role in violence and criminality. The goal of the intervention was to reduce the patient’s reliance on maladaptive coping modes.

Doyle et al’s intervention19 was an adaptation of Young and colleagues’ treatment protocol for patients with personality disorder.33

Solution-focused brief therapy

This was used by one study. MacInnes et al 23 used a computer-assisted approach using SFBT. The therapy promotes movement towards positive change in individuals and is characterised by a focus on the future exploring what will be different when things are better.34

Effect of intervention

The outcomes of the interventions are reported in table 2, while an overview of whether the intervention reported improved or worse outcomes is shown in table 3.

Table 2.

Table of outcomes

| Outcome | Authors | Measure | Intervention | Control | Estimated effect (and p value if recorded) |

| Time point | |||||

| Mean scores (SD) OR Number of events* | |||||

| Disturbance | Cullen et al 18 | Mean no. of leave | Post treat 0.33 (0.82) | Post treat 0.83 (2.25) | Mean diff: −0.5, p=0.02 |

| Violations | 12 months post 0.52 (0.99) | 12 months post 0.60 (1.19) | Mean diff: −0.08, p=0.74 | ||

| MacInnes et al 23 | 6 months post. | 6 months post | |||

| No. of absconsions | 2 | 7 | Diff: −5 | ||

| No. of physical restraints | 22 | 35 | Diff: −13 | ||

| Quality of life | Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Sintonen’s 15D health-related quality of life | Post treat 0.9 (0.08) | Post treat 0.91 (0.06) | Mean diff: −0.,1 p=0.5 |

| 3 months post 0.9 (0.06) | 3 months post 0.94 (0.08) | Mean diff: −0.2, p=0.09 | |||

| MacInnes et al 23 | Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life | Post treat 4.5 (0.4) | Post treat 4.3 (0.1) | Mean diff: 0.2 | |

| 6 months post 4.7 (0.2) | 6 Months post 4.3 (0.3) | Mean diff: 0.4 | |||

| Walker et al 27 | Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 | Post treat 30.7 (19.1) | Post treat 30.6 (16.1) | Mean diff: 0.1, p=0.20 | |

| 6 months post 29 (16.6) | 6 months post | ||||

| Not reported | |||||

| Recovery | Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Scale to assess | Post treat 4.1 (0.9) | Post treat 4.7 (1.0) | Mean diff: −0.6P=0.67 |

| Unawareness of mental disorder | 3 months post 3.8 (1.1) | 3 months post 4.8 (0.8) | Mean diff: 1.0 p=0.09 | ||

| MacInnes et al 23 | Process of recovery questionnaire | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Interpersonal | 66.4 (2.0) | 64.1 (2.0) | Mean diff: 2.3 | ||

| Intrapersonal | 18.9 (0.4) | 19.0 (0.7) | Mean diff: −0.1 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Interpersonal | 65.6 (1.0) | 63.9 (1.1) | Mean diff: 1.7 | ||

| Intrapersonal | 18.9 (0.7) | 19.7 (0.9) | Mean diff: −0.8 | ||

| Walker et al 27 | Schedule for assessment of insight | Post treat | Post treat | Mean diff: 1.5, p=0.13 | |

| 12.2 (5.4) | 10.7 (5.1) | ||||

| 6 months post 13.5 (4.5) | 6 months post | ||||

| Not reported | |||||

| Satisfaction | MacInnes et al 23 | Forensic Satisfaction Scale | Post treat 3.3 (0.2) | Post treat 3.3 (0.3) | Mean diff: 0 |

| 6 months post 3.3. (0.1) | 6 months post 3.3. (0.1) | Mean diff: 0 | |||

| Seclusion | MacInnes et al 23 | No. of seclusions | 6 months post | 6 months post | Diff: −28 |

| 9 | 37 | ||||

| Symptoms | Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Beck Depression Inventory-II | Post treat 8.1 (5.7) | Post treat 11.2 (4.5) | Mean diff: −3.1, p=0.46. |

| 3 months post 6.4 (6.2) | 3 months post 13.1 (7.9) | Mean diff: −6.7, p=0.30. | |||

| Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | Post treat 27.9 (7.5) | Post treat 28.1 (5.4) | Mean diff: −0.2, p=0.57. | |

| 3 months post 26.5 (8.0) | 3 months post 28.5 (4.6) | Mean diff: −2.0, p=0.76. | |||

| Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | Post treat 29.7 (3.6) | Post treat 29.3 (2.9) | Mean diff: 0.4, p=0.03. | |

| 3 months post 29.4 (2.8) | 3 months post 29.5 (4.3) | Mean diff: −0.1, p=0.06. | |||

| Aho-Mustonen et al 15 | Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation-30 | Post treat 100.6 (3.7) | Post treat 101 (4.3) | Mean diff: −0.4, p=0.77. | |

| 3 months post 99.2 (3.8) | 3 months post 100.8 (3.9) | Mean diff: 1.6, p=0.31. | |||

| Doyle et al 19 | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | No raw scores reported | 24 months post* | ||

| 0.29, p=0.74 | |||||

| Haddock et al 21 | Global Assessment of Functioning | Post treat 41.86 (15.63) | Post Treat 33.34 (14.64) | Mean diff: 8.52 | |

| 6 months post 42.94 (19.30) | 6 months post 40.93 (22.06) | Mean diff::2.01 | |||

| Haddock et al 21 | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Positive | 14.79 (5.95) | 11.66 (3.67) | Mean diff: 3.13 | ||

| Negative | 15.75 (5.70) | 13.50 (5.59) | Mean diff: 2.25 | ||

| General | 55.24 (12.47) | 58.68 (16.14) | Mean diff: −3.44 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Positive | 15.03 (6.97) | 12.06 (4.91) | Mean diff: 2.97 | ||

| Negative | 15.88 (5.66) | 14.31 (6.08) | Mean diff: 1.57 | ||

| General | 53.97 (20.27) | 57.73 (16.31) | Mean diff: −3.76 | ||

| Haddock et al 21 | Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Auditory | 9.74 (13.92) | 11.38 (15.13) | Mean diff: −1.64 | ||

| Delusions | 4.90 (6.55) | 11.04 (6.70) | Mean diff: −6.14 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Auditory | 9.36 (12.72) | 10.83 (16.63) | Mean diff: −1.47 | ||

| Delusions | 7.60 (8.25) | 8.38 (8.03) | Mean diff: −0.78 | ||

| Walker et al 27 | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Positive | 12.8 (3.9) | 14.3 (6.2) | Mean diff: −1.5 | ||

| Negative | 15.2 (6.2) | 17.9 (6.9) | Mean diff: −2.7 | ||

| General | 27.2 (7.2) | 30.4 (9.8) | Mean diff: −3.2 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Positive | 12.5 (7.2) | Not reported | |||

| Negative | 14.1 (6.3) | Not reported | |||

| General | 27.8 (10.8) | Not reported | |||

| Walker et al 27 | Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia | Post treat 1.8 (4.4) | Post treat 2 (3.46) | Mean diff: −0.2, p=0.32 | |

| 6 months post 1.8 (3.6) | 6 months post | ||||

| Not reported | |||||

| Therapeutic relationship | MacInnes et al 23 | Helping Alliance Scale | Post treat 6.6 (0.6) | Post treat 6.3 (0.5) | Mean diff: 0.3 |

| 6 months post 7.0 (0.8) | 6 months post 6.7 (0.2) | Mean diff: 0.3 | |||

| Violence/risk | Bernstein et al 16 | Historical, Clinical, Risk Management-20 | No raw scores recorded | Higher scores in control group. No statistically significant p values reported. | |

| Cullen et al 18 | Mean acts of aggression per patient | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Verbal | 3.95 (8.42) | 3.53 (6.44) | Mean diff: 0.42, p=0.01 | ||

| Physical | 0.55 (1.38) | 0.68 (1.33) | Mean diff: −0.13, p=0.11 | ||

| 1 year post | 1 year post | ||||

| Verbal | 7.33 (10.83) | 8.23 (15.71) | Mean diff: −0.9, p=0.02 | ||

| Physical | 0.90 (1.96) | 0.88 (2.00) | Mean diff: 0.02, p=0.65 | ||

| Cullen et al 18 | Novaco Anger Scale | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Cognitive | 28.5 (5.0) | 27.3 (4.9) | Mean diff: 1.2 | ||

| Arousal | 24.9 (5.2) | 25.5 (5.4) | Mean diff: −0.6 | ||

| Behavioural | 23.8 (5.3) | 25.6 (5.7) | Mean diff: −1.8 | ||

| 1 year post | 1 year post | ||||

| Cognitive | 28.6 (5.4) | 27.7 (4.9) | Mean diff: 0.9 | ||

| Arousal | 27.5 (6.3) | 24.7 (5.3) | Mean diff: 0.8 | ||

| Behavioural | 25.1 (5.4) | 24.2 (4.8) | Mean diff: 0.9 | ||

| Doyle et al 19 | Mean acts of physical, verbal or property aggression | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| 2.32 | 1.32 | Mean diff: 1.0 | |||

| Doyle et al 19 | Novaco Anger Scale | 24 months post* | |||

| Cognitive | −0.57, p=0.47 | ||||

| Arousal | No raw scores reported | −0.92, p=0.35 | |||

| Behavioural | 0.44, p=0.65 | ||||

| Total | 0.27, p=0.91 | ||||

| Doyle et al 19 | Historical, Clinical, Risk Management 20 | 24 months post* | |||

| Risk | No raw scores reported | 0.12, p=0.73 | |||

| Clinical | −0.19, p=0.69 | ||||

| Doyle et al 19 | Violence risk | No raw scores reported | 24 months post* | ||

| Scale total | −3.43, p=0.04 | ||||

| Haddock et al 11 | No. of incidents of aggression | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Verbal | 31 | 103 | Diff: −72, p=0.15 | ||

| Physical | 2 | 46 | Diff: −44, p=0.039 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Verbal | 34 | 80 | Diff: −46, p=0.765 | ||

| Physical | 5 | 22 | Diff: −17, p=0.594 | ||

| Haddock et al 21 | Ward Anger Rating Scale B | Post treat 4.03 (4.19) | Post treat 6.36 (6.79) | Mean diff: −2.33 | |

| 6 months post 4.2 (4.65) | 6 months post 6.3 (8.00) | Mean diff: −2.1 | |||

| Haddock et al 21 | Novaco Anger Scale | Post treat 88.13 (16.88) | Post treat 82.36 (20.12) | Mean diff: 5.77 | |

| 6 months post | 6 months post | Mean diff: 1.1 | |||

| 85.51 (17.33) | 84.41 (22.62) | ||||

| Haddock et al 21 | Novaco Provocation Inventory | Post treat 59.75 (18.51) | Post treat 55.63 (17.51) | Mean diff: 4.12 | |

| 6 months post 61.65 (13.15) | 6 months post 58.32 (18.01) | Mean diff: 3.33 | |||

| Haddock et al 21 | Historical, Clinical, Risk Management 20 | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Risk | Not reported | Not reported | |||

| Clinical | Not reported | Not reported | |||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Risk | 4.00 (3.96) | 4.23 (2.83) | Mean diff: −0.23 | ||

| Clinical | 3.57 (2.54) | 4.03 (2.64) | Mean diff: −0.46 | ||

| Hakvoort et al 22 | Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale | 6 months post 2.56 | 6 months post 2.4 | Mean diff: 0.16, p=0.34 | |

| Hakvoort et al 22 | Atascadero Skills Profiles Scale 4 | 6 months post 2.51 | 6 months post 2.01 | Mean diff: 0.5, p=0.86 | |

| MacInnes et al 23 | No. of violent incidents | 6 months post 50 | 6 months post 96 | Mean diff: −46 | |

| Tomlinson and Hoaken25 | Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire -SF | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Overall | 2.05 (0.47) | 2.14 (0.88) | Mean diff: −0.09 | ||

| Physical | 2.13 (0.90) | 2.87 (1.87) | Mean diff: −0.74 | ||

| Verbal | 2.07 (0.43 | 1.67 (0.47) | Mean diff: 0.4 | ||

| Hostility | 2.20 (0.96) | 2.26 (0.95) | Mean diff: −0.06 | ||

| Anger | 1.80 (0.56) | 2.26 (0.89) | Mean diff: −0.46 | ||

| Tomlinson and Hoaken25 | Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scale | Post treat | Post treat | ||

| Overall | 2.23 (0.21) | 2.94 (0.59) | Mean diff: −0.71 | ||

| Premediated aggression | 2.00 (0.27) | 2.75 (0.91) | Mean diff: −0.75 | ||

| Impulsive aggression | 2.40 (0.20) | 3.09 (0.57) | Mean diff: −0.89 | ||

| Walker et al 27 | Behaviour Status Index | Post treat 572 (99.1) | Post treat 535.7 (96.2) | Mean diff: 34.3, p=0.41 | |

| 6 months post 559 (86.3) | 6 months post | ||||

| Not reported | |||||

| Ward environment | MacInnes et al 23 | Essen Climate Evaluation Schema | Post treat | Post treat | |

| Patient cohesion | 8.8 (1.0) | 9.3 (0.7) | Mean diff: −0.5 | ||

| Experienced safety | 15.4 (1.2) | 16.3 (2.4) | Mean diff: −0.9 | ||

| Therapeutic hold | 10.7 (1.5) | 11.6 (1.2) | Mean diff: −0.9 | ||

| 6 months post | 6 months post | ||||

| Pt cohesion | 10.6 (0.2) | 9.3 (0.7) | Mean diff: 1.3 | ||

| Experienced safety | 16.3 (2.3) | 15.4 (2.7) | Mean diff: 0.9 | ||

| Therapeutic hold | 11.7 (1.0) | 12.2 (0.5) | Mean diff: −0.5 |

Notes: Aho-Mustonen et al.15 The p values relate to the differences in mean change scores from baseline at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up on outcome measures between the groups.

*A positive estimate indicates that the mean effect size for that variable is higher in the control group. A negative estimate (−) means that it is lower.

Table 3.

Type of intervention content and number of interventions effective for each outcome (n=9 studies)

| Psychoeducation | CBT | SFT | SFBT | DBT | ||||||

| Better | Worse | Better | Worse | Better | Worse | Better | Worse | Better | Worse | |

| Disturbance | n/a | n/a | 2 (1) | 0 | n/a | n/a | 2 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Quality of life | 0 | 3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Recovery | 2 | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 2 | n/a | n/a |

| Therapeutic relationship | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Satisfaction | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Seclusion | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

| Symptoms | 11 (1) | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ward environment | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 4 (1) | n/a | n/a |

| Violence/risk | 1 | 0 | 13 (2) | 11 (1) | 3 | 5 (1) | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

The values in parentheses record the number of statistically signficant differences.

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; n/a, not applicable as no comparison undertaken; SFBT, solution-focused brief therapy; SFT, schema-focused therapy.

Time points

All studies detailed the baseline assessments with the scores for the intervention and control group comparable at baseline. The studies also reported assessment scores immediately post treatment (except ref 22), at 3-month post-treatment,15 6-month post-treatment21–23 27 and 1-year post-treatment.18 Doyle et al 19 recorded scores at 6, 12 and 24 months and Bernstein et al 16 at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months.

Outcomes

Nine of the 10 outcomes of interest were reported in the studies. Eight studies reported violence/risk outcomes, four reported symptoms outcomes, three reported quality of life outcomes, three studies reported recovery outcome and two studies reported disturbance with one study reporting on therapeutic relationship/engagement, satisfaction, ward environment/atmosphere and seclusion. There were no reported outcomes for well-being.

Two of studies did not report any raw scores. Doyle et al 19 reported the outcomes at the three different follow-up times (6, 12 and 24 months) with these analysed simultaneously in a repeated measures analysis using all available data and recording the estimated treatment effects (group differences) and p values. Bernstein et al 16 used repeated measures analysis of variance to analyse the effect of SFT versus TAU on Historical Clinical Risk Management- 20 (HCR-20) scores over the course of treatment. They did not analyse other outcome variables because of the low statistical power in the sample.

Overall, there were few significant findings with only 7 reported out of 91 statistical comparisons.

Violence/risk

Seventeen violence/risk outcomes were recorded by eight studies.16 18 19 21–23 25 27 Four significant findings were reported, which was more than for any other outcome. Two significant outcomes reported an improvement for the intervention group and two for the control group with significant findings only recorded at one time point. Rates of verbal aggression reported by Cullen et al 18 were higher in the intervention group during the treatment period with an incident rate ratio (IRR) of 0.48 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.85) though higher in the control group in the 12-month post treatment with an IRR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.91). Haddock et al 21 recorded the CBT group had a significantly lower number of incidents of violence or aggression during the treatment period, while Doyle et al 19 reported that the intervention scores were significantly lower in the control group with an effect size of −3.43. No other statistically significant findings were found by these two studies using the seven other violence/risk measures. The majority of the studies examining violence/risk outcomes used a CBT or SFT intervention. The information in table 3 suggests an approximately 61% (25 out of 41) improvements were recorded in the intervention groups using these approaches. Tomlinson and Hoaken25 reported reduced levels of violence self-reported aggressive behaviour using DBT as an intervention but was undertaken with a small sample with several potential risks of bias present. Overall, there does not appear to be any consistency between the significant scores recorded and little difference in the number of improvements reported.

Symptoms

Ten outcomes were recorded by four studies15 19 21 27 with a wide variety of different symptoms measured. Only one significant finding was reported; the intevention group reported higher levels of self-esteem post-treatment.15 This difference was not maintained at the 3 months post treatment assessment. The main interventions reporting symptoms as outcomes used a psychoeducational or CBT approach. In table 3, 79% of the outcomes (19 out of 24) show an improvement for those patients in receipt of an intervention. It gives some support to the view that interventions are able to improve symptoms though how much improvement is achieved or whether certain symptoms are more amenable to certain interventions is unclear.

Quality of life

There was little difference in scores between the intervention and control groups recorded in the five outcomes reported by three studies.15 23 27 The psychoeducational approach was used as an intervention in two studies. All three outcomes reported a slightly lower non-significant quality of life in the intervention. The SFBT study reported improved quality of life scores post-treatment and 6-month post-treatment giving cautious support to the view this approach may be effective.

Recovery

Three studies recorded three recovery outcomes.15 23 27 This outcome was reported for psychoeducational and SFBT interventions with no significant differences noted. The psychoeducational outcomes reported better scores for those in the intervention group tentatively suggesting the psychoeducational approach may help recovery. The SFBT results were more equivocal.

Disturbance

Two studies recorded three different types of disturbance outcome.18 23 A CBT intervention18 reported less leave violations during the treatment period and remained lower (though non-significant) in the year following the end of treatment. The SFBT study23 reported lower levels of absconsions and less physical restraints for the intervention group. These findings give initial indications these approaches may reduce levels of disturbance

Other outcomes

Four further outcomes (satisfaction, seclusion, therapeutic relationship and ward environment/atmosphere) were assessed by one study.23 Better therapeutic relationships were reported for the intervention group at both time points suggesting a potential improvement using this approach. There were also reduced numbers of seclusions for the intervention group during the 6-month follow-up period. No differences were reported in the satisfaction scores between the intervention and control groups, while the ward environment scores suggest a better atmosphere in the control group including one statistically significant result (patient cohesion) post treatment.

Risk of bias of evidence

The majority of domains had a low risk of bias (figure 2). In relation to the potential of performance bias, we determined that participants and staff would be aware of which arm of the trial they have been allocated but any performance bias would be minimal. We, therefore rated these studies as having a low risk. There were difficulties with recruitment and attrition adding to the limitations of the small sample sizes of the studies. Five of the studies reported problems with recruitment with between 23% and 29.4% of patients deemed as eligible refusing to participate. Three studies were rated as high risk of attrition bias due to incomplete outcome data18 19 27 with two studies reporting over 50% of their intervention group not completing the sessions.18 19

Figure 2.

Risk of bias table.

Six studies were able to limit detection bias through ensuring the blinding of the raters of the outcome assessments. One study where blinding was not performed acknowledged the participants may have shown social desirability bias,25 while another used raters who were blind to patients’ treatment condition status double-scored a subset of these assessments with good levels of inter-rater agreement recorded.13

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review found a total of nine published RCTs examining psychological and psychosocial interventions in forensic mental health inpatient settings deliverable to any patient residing in a forensic mental health inpatient setting. The studies were heterogeneous resulting in a narrative review of the main findings. There were few statistically significant findings reported; only 7 out of the 91 comparisons analysed, and none of these significant findings revealed a consistent result. This indicates the current evidence base for supporting any psychological or psychosocial intervention is limited. Table 3 gives some indication of areas where particular interventions may have a positive benefit, though with the lack of significant differences recorded, these findings need to be treated with caution. In general, psychoeducational approaches reported improvements in recovery and symptom outcomes and poorer findings for quality of life outcomes. The CBT interventions noted improved findings for absconding and symptoms outcomes, though the impact on violence/risk was more equivocal. A similar finding is noted in relation to the SFT intervention with an equal amount of better and worse outcomes recorded for measures of violence/risk. The DBT intervention show promising results for reducing violence/risk, while the SFBT approach reported improved quality of life, therapeutic relationships and reduced disturbed behaviour. However, the results of both interventions are based on single small-scale studies indicating more extensive studies are required to produce clearer evidence. This review suggests that psychological and psychosocial interventions do not reduce violence/risk in this group of patients, though there is some tentative support that the interventions may improve mental health symptoms.

A number of other factors may have contributed to these findings: individual study designs were quite different, a variety of different secure settings were included with two studies recruiting from different levels of security21 27 and most studies were recruited from multiple sites. The interventions may have had different impacts due to differences in the therapeutic uses of security and related legal governance systems.2 The study sample sizes were small ranging from 14 to 112 participants. This lack of statistical power limited the ability of the study to detect treatment differences.21 The representativeness of the findings was reduced through most studies only including participants with either a diagnosis of psychosis or personality disorder and by the small number of women participating. The paucity of women participants in forensic research has been viewed as indicative of the realities of research undertaken in this area where basic services to women were often poor or lacking.35 One study noted the significant number of women withdrawing from the study when compared with men and suggested examining reasons for higher dropout rates and whether specific support was required during the intervention.23 The time line of the intervention varied considerably from eight weekly sessions of psychoeducation15 to twice weekly sessions of schema therapy for 3 years.16 The recording of the control group intervention varied greatly and consisted of widely differing approaches. There were also differences between the number of treatment sessions offered to the intervention and control groups. Only one study offered both groups the same number of therapy sessions.21 It is possible that the different treatment intensity may have influenced the outcomes.16 The lack of standardised outcomes was also problematic. Thirty-one outcomes measures were used, with only five measures used more than once, making it difficult to draw conclusions across studies.13

Other reviews of research in forensic mental health settings have reported similar difficulties preventing a homogenous dataset36–39 with few studies with enough similarities to each other to draw firm conclusions regarding the impact of interventions.36 Continuing with small-scale research with mentally disordered offenders (MDOs) is questionable due to these studies being underpowered and unlikely to detect differences.37 Future studies would benefit from larger sample sizes that include representative groups of the forensic inpatient population. It is likely that multisite studies will need to be undertaken with the impact of different environments reviewed as part of the study. To increase the homogeneity of studies, future studies also need similar participants, interventions and outcome measures.36 Using measures that are familiar in practice might be a productive way of developing standardised outcomes.13

Strengths

The majority of studies included in the review had a low risk of bias, indicating it is possible to conduct well-designed RCTs in forensic mental health inpatient settings.10 RCTs remain the gold standard for investigating the effectiveness of treatments and are needed to determine beneficial interventions for this group of patients.16 The randomisation procedures worked well in the majority of the studies. Seven studies reported on the fidelity of the intervention approach with staff trained in the specific procedures. The intervention approaches were competently performed with only one study19 noting that therapists providing the intervention may not have met relevant standards. Most studies were also able to blind researchers to allocation status when assessing outcomes.

Limitations

The review excluded non-English language publications that may have led to some relevant research not being included in the review. Some limitations were noted with recruitment and attrition. Five studies reported that approximately 25% or more of the patients approached declined to participate. It was likely the patients who declined to participate were more unwell and/or antisocial, and these factors might have influenced treatment outcomes.40 Attrition was also a problem, which is not surprising considering the high levels of anti-social behaviour and non-compliance prevalent in this cohort.41 Overall, 25% of participants withdrew or dropped out of the studies. Those limitations that took longer to complete or that required a high level of weekly committment were more likely to record a greater number of dropouts and withdrawals.

Conclusions

This is the first review to specifically examine psychological or psychosocial interventions (A) accessible to the majority of patients in forensic mental health inpatient settings and (B) focusing only on RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions. Nine RCTs were found. The current evidence from these studies suggests current practice is based on limited evidence with no consistent significant findings. These interventions may have the potential to improve some outcomes, particularly symptoms, using CBT or psychoeducational approaches. The individual DBT and SFBT studies also report promising results. However, the limitations in the conduct of the studies mean specific psychological or psychosocial interventions cannot be supported at present. The studies’ low risk of bias assessments supports the view that good quality RCTs are able to be undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions. If more RCTs are undertaken, the evidence base will become clearer. As highlighted in our analysis, the existing evidence base is too diverse for it to be reliable. A key priority for the future is that efforts are placed in devising a standardised framework of reference for study protocols. More specifically, future trials would benefit from: a larger sample size, ensuring participants are representative of the overall forensic inpatient population, using standardised outcomes and clearly detailing control group interventions that are similar in treatment intensity to the intervention. Further work would also be helpful to look at ways of addressing problems concerning rates of recruitment and attrition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support received from Dr Dan Bressington, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Footnotes

Contributors: The review was designed by DM. SM undertook the literature search. The risk of bias assessment, data extraction, analysis of the data and data interpretation were undertaken by SM and DM. DM wrote the first draft of the paper. Both authors reviewed successive drafts and approved the revised manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Adshead G. Care or custody? Ethical dilemmas in forensic psychiatry. J Med Ethics 2000;26:302–4. 10.1136/jme.26.5.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tapp J, Perkins D, Warren F, et al. A critical analysis of clinical evidence from high secure forensic inpatient services. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2013;12:68–82. 10.1080/14999013.2012.760185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buchanan A, Grounds A. Forensic psychiatry and public protection. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:420–3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnao M, Ward T. Sailing uncharted seas without a compass: a review of interventions in forensic mental health. Aggress Violent Behav 2015;22:77–86. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cavezza C, Aurora M, Ogloff JRP. The effects of an adherence therapy approach in a secure forensic hospital: a randomised controlled trial. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2013;24:458–78. 10.1080/14789949.2013.806568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD007667 10.1002/14651858.CD007667.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gibbon S, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Psychological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD007668 10.1002/14651858.CD007668.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dennis JA, Khan O, Ferriter M, et al. Psychological interventions for adults who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD007507 10.1002/14651858.CD007507.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan O, Ferriter M, Huband N, et al. Pharmacological interventions for those who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007989 10.1002/14651858.CD007989.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duggan C, Dennis J. The place of evidence in the treatment of sex offenders. Crim Behav Ment Health 2014;24:153–62. 10.1002/cbm.1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harkness E, Bower P. Cochrane effective practice and organisation of care group. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dennis CL, Dowswell T. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD001134 10.1002/14651858.CD001134.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fitzpatrick R, Chambers J, Burns T, et al. A systematic review of outcome measures used in forensic mental health research with consensus panel opinion. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:18 10.3310/hta14180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aho-Mustonen K, Tiihonen J, Repo-Tiihonen E, et al. Group psychoeducation for long-term offender patients with schizophrenia: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. Crim Behav Ment Health 2011;21:163–76. 10.1002/cbm.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernstein DP, Nijman HLI, Karos K, et al. Schema therapy for forensic patients with personality disorders: design and preliminary findings of a multicenter randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2012;11:312–24. 10.1080/14999013.2012.746757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clarke AY, Cullen AE, Walwyn R, et al. A quasi-experimental pilot study of the Reasoning and Rehabilitation programme with mentally disordered offenders. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2010;21:490–500. 10.1080/14789940903236391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cullen AE, Clarke AY, Kuipers E, et al. A multi-site randomized controlled trial of a cognitive skills programme for male mentally disordered offenders: social-cognitive outcomes. Psychol Med 2012;42:557–69. 10.1017/S0033291711001553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doyle M, Tarrier N, Shaw J, et al. Exploratory trial of schema-focussed therapy in a forensic personality disordered population. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2016;27:232–47. 10.1080/14789949.2015.1107119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evershed S, Tennant A, Boomer D, et al. Practice-based outcomes of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) targeting anger and violence, with male forensic patients: a pragmatic and non-contemporaneous comparison. Crim Behav Ment Health 2003;13:198–213. 10.1002/cbm.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haddock G, Barrowclough C, Shaw JJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy v. social activity therapy for people with psychosis and a history of violence: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:152–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hakvoort L, Bogaerts S, Thaut MH, et al. Influence of Music Therapy on Coping Skills and Anger Management in Forensic Psychiatric Patients: An Exploratory Study. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2015;59:810–36. 10.1177/0306624X13516787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacInnes D, Kinane C, Parrott J, et al. A pilot cluster randomised trial to assess the effect of a structured communication approach on quality of life in secure mental health settings: The Comquol Study. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:335 10.1186/s12888-016-1046-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rees-Jones A, Gudjonsson G, Young S. A multi-site controlled trial of a cognitive skills program for mentally disordered offenders. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:44 10.1186/1471-244X-12-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tomlinson MF, Hoaken PNS. The potential for a skills-based dialectical behavior therapy program to reduce aggression, anger, and hostility in a canadian forensic psychiatric sample: a pilot study. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2017;16:215–26. 10.1080/14999013.2017.1315469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van den Broek E, Keulen-de Vos M, Bernstein DP. Arts therapies and schema focused therapy: a pilot study. Arts Psychother 2011;38:325–32. 10.1016/j.aip.2011.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walker H, Tulloch L, Ramm M, et al. A randomised controlled trial to explore insight into psychosis; effects of a psycho-education programme on insight in a forensic population. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2013;24:756–71. 10.1080/14789949.2013.853821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Joy Tong LS, Farrington DP. How effective is the “Reasoning and Rehabilitation” programme in reducing reoffending? A meta-analysis of evaluations in four countries. Psychology, Crime & Law 2006;12:3–24. 10.1080/10683160512331316253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ross RR, Fabiano EA, Ewles CD. Reasoning and Rehabilitation. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 1988;32:29–35. 10.1177/0306624X8803200104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioural treatment of borderline personality disorder. NewYork: Guilford Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Donker T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, et al. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2009;7:79 10.1186/1741-7015-7-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Connaugton J, Walker H, Cawthorne P, et al. Coping with mental illness: a psycho-education programme for psychosis. Carstairs: The State Hospital, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Young J, Klosko J, Weishaar M. Schema therapy: a practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iveson C. Solution-focused brief therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2002;8:149–56. 10.1192/apt.8.2.149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bartlett A, Jhanji E, White S, et al. Interventions with women offenders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health gain. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2015;26:133–65. 10.1080/14789949.2014.981563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hockenhull JC, Cherry MG, Whittington R, et al. Heterogeneity in interpersonal violence outcome research: an investigation and discussion of clinical and research implications. Aggress Violent Behav 2015;22:18–25. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Duncan EA, Nicol MM, Ager A, et al. A systematic review of structured group interventions with mentally disordered offenders. Crim Behav Ment Health 2006;16:217–41. 10.1002/cbm.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sturgeon M, Tyler N, Gannon TA. A systematic review of group work interventions in UK high secure hospitals. Aggress Violent Behav 2018;38:53–75. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farrington D, Jolliffe D. A feasibility study into using a randomised controlled trial to evaluate treatment pilots at HMP Whitemoor. London: Home Office Online Report 14/02, 2002. www.citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.629.3353&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 7 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cullen AE, Clarke AY, Kuipers E, et al. A multisite randomized trial of a cognitive skills program for male mentally disordered offenders: violence and antisocial behavior outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:1114–20. 10.1037/a0030291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tarrier N, Dolan M, Doyle M, et al. Exploratory randomised control trial of schema modal therapy in the personality disorder service at Ashworth Hospital. London: Ministry of Justice Research Series 5/10, 2010. www.ohrn.nhs.uk/resource/policy/RCTSchema.pdf (accessed 7 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.