Abstract

Background and objective

Pediatrics: Omission of Prescription and Inappropriate prescription (POPI) is the first detection tool for potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) and potentially prescribing omissions (PPOs) in paediatrics. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of PIM and PPO detected by POPI regarding prescriptions in hospital and for outpatients. The second objective is to determine the risk factors related to PIM and PPO.

Design

A retrospective, descriptive study was conducted in the emergency department (ED) and community pharmacy (CP) during 6 months. POPI was used to identify PIM and PPO.

Setting

Robert-Debré Hospital (France) and Albaret community pharmacy (Seine and Marne).

Participants

Patients who were under 18 years old and who had one or more drugs prescribed were included. Exclusion criteria consisted of inaccessible medical records for patients consulted in ED and prescription without drugs for outpatients.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

PIM and PPO rate and risk factors.

Results

At the ED, 18 562 prescriptions of 15 973 patients and 4780 prescriptions of 2225 patients at the CP were analysed. The PIM rate and PPO rate were, respectively, 2.9% and 2.3% at the ED and 12.3% and 6.1% at the CP. Respiratory and digestive diseases had the highest rate of PIM.

Conclusion

This is the first study to assess the prevalence of PIM and PPO detected by POPI in a paediatric population. This study assessed PIMs or PPOs within a hospital and a community pharmacy. POPI could be used to improve drug use and patient care and to limit hospitalisation and adverse drug reaction. A prospective multicentric study should be conducted to evaluate the impact and benefit of implementing POPI in clinical practice.

Keywords: inappropriate prescription, omission, tool, detection

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to observe the prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicine (PIM) and potentially prescribing omission (PPO) in a paediatric population.

It is a retrospective and monocentric study. The prevalence of PIM and PPO may be underestimated (large number of prescriptions and absence of specific pathology). Some criteria could only be analysed in a prospective study. The lack of clinical information is the main limit to detection in a community setting.

Many omissions and inappropriate prescriptions can be easily detected with POPI despite limited clinical information.

Introduction

Inappropriate prescribing is a known preventable cause of adverse drug events (ADEs) and has an important impact on public health and cost of care.1 2 In the literature, ADE is defined by ‘an injury resulting from medical intervention related to a drug’ (dose error, adverse drug reaction (ADR) and misuse of medication such as antibiotics).3–5 In the paediatric population, ADR during hospitalisation was estimated between 0.6% and 33.7% and between 1% and 1.5% for outpatients.6–9 Incidence of ADR leading to admission was evaluated between 1.8% and 17.7%.6 7 10 Many drugs were concerned in commonly used medication.11–13

The WHO estimated that 50% of medications are prescribed and used inappropriately.14 The most recent definition of inappropriate prescription (IP) encompasses potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) and potentially prescribing omissions (PPOs).15 In a report from the French National Authority for Health, PIMs are defined as ‘drugs being used in a situation in which the risks involved in treatment potentially outweigh the benefits, lack of demonstrated indication, high risk of ADE, or an unfavorable cost-effect or risk-benefit ratio exists’. PPO or underuse of appropriate medication is defined as the absence of initiation of an effective treatment in subjects with a condition for which one or several drug classes have demonstrated their efficacy. In an elderly population, which presents with age-related physiological changes and high prevalence of polypharmacy, various measures have been developed to detect PIM such as: Beers’ criteria, the Inappropriate Prescribing in the Elderly Tool, The Medication Appropriate Index and Screening Tool of Older Person’s prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctor to Right Treatment (STOPP/START).16–21

Only the STOPP/START enables us to detect underprescription.15 Using these tools, many studies have been carried out which have detected that IPs range from 35% to 51% in the above population.22–26

Omission of prescriptions in geriatric population detected by the START tool concerned 58%–61% of patients.27 28 Negative outcomes related to an IP such as side effects, hospitalisation, mortality and utilisation of resources were also highlighted.2 21 29 30

Prescribing in a paediatric population is always challenging for physicians. It is often empirical and primarily based on safety and pharmacology information obtained in adults.31 This is a worry in a hospital or general practitioner setting and for the community pharmacists. With many off-label uses, they may be obligated to find alternative information sources and might even dispense infrequently for this vulnerable population.32 ADRs are three time higher in paediatric populations. This frequency is explained by the vulnerability of children, pharmacokinetic changes during childhood and paediatric off-label drug used.4 33 Large differences relating to treatment were seen within and between countries.6 34 Questions about the rationale of prescriptions could be asked.35 Optimising children’s care is based on rational prescribing and aims for a decrease in side effects.34 35 In order to improve the correct drug use and optimise practice, the first tool of detection for PIM and PPO was created by Prot-Labarthe et al in 2013. The tool was named Pediatrics: Omission of Prescriptions and Inappropriate prescriptions (POPI) (table 1).36 37 Presently, the complete tool has yet to be tested in clinical practice, and the prevalence of PIM and PPO is not known.

Table 1.

Pediatrics: Omission of Prescriptions and Inappropriate prescriptions (POPI)

| Diverse illnesses | |

| A: pain and fever | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| AI-1. Prescription of two alternating antipyretics as a first-line treatment. AI-2. Prescription of a medication other than paracetamol as a first-line treatment (except in the case of migraine). AI-3. Rectal administration of paracetamol as a first-line treatment. AI-4. The combined use of two NSAIDs.*† AI-5. Oral solutions of ibuprofen administered in more than three doses per day using a graduated pipette of 10 mg/kg (other than Advil).† AI-6. Opiates to treat migraine attacks.* |

A0-1. Failure to give sugar solution to new-born babies and infants under 4 months old 2 min prior to venipuncture. A0-2. Failure to give an osmotic laxative to patients being treated with morphine for a period of more than 48 hours. |

| B: urinary infections | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| BI-1. Nitrofurantoin used as a prophylactic.* BI-2. Nitrofurantoin used as a curative agent in children under 6 years of age or indeed any other antibiotic if avoidable.* BI-3. Antibiotic prophylaxis following an initial infection without complications (except in the case of uropathy).* BI-4. Antibiotic prophylaxis in the case of asymptomatic bacterial infection (except in the case of uropathy).* |

|

| C: vitamin supplements and antibiotic prophylaxis | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| CI-1. Fluoride supplements prior to 6 months of age. †* |

CO-1. Insufficient intake of vitamin D. Minimum vitamin D intake:

|

| D: mosquitos | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| DI-1. The use of skin repellents in infants less than 6 months old and picardin in children less than 24 months old. DI-2. Citronella (lemon grass) oil (essential oil). DI-3. Anti-insect bracelets to protect against mosquitos and ticks. DI-4. Ultrasonic pest control devices, vitamin B1, homeopathy, electric bug zappers and sticky tapes without insecticide. |

DO-1. DEET ‘30%’ (max) before 12 years old. ‘50%’ (max) after 12 years old. DO-2. IR3535 ‘20%’ (max) before 24 months old. ‘35%’ (max) after 24 months old. DO-3. Mosquito nets and clothes treated with pyrethroids. |

| Digestive Problems | |

| E: nausea, vomitting or gastro-oesophageal reflux | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| EI-1. Metoclopramide.*† EI-2. Domperidone.*† EI-3. Gastric antisecretory drugs to treat gastro-oesophageal reflux, dyspepsia, the crying of new-born babies (in the absence of any other signs or symptoms), as well as faintness in infants.* EI-4. The combined use of proton pump inhibitors and NSAIDs, for a short period of time, in patients without risk factors.* EI-5. Oral administration of an intravenous proton pump inhibitor (notably by nasogastric tube).* EI-6. The use of type H2 antihistamines for long periods of treatment.* † EI-7. Erythromycin as a prokinetic agent.* EI-8. The use of setrons (5-HT3 antagonists) for chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting.* |

EO-1. Oral rehydration solution in the event of vomiting.* |

| F: diarrhoea | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| FI-1. Loperamide before 3 years of age.*† FI-2. Loperamide in the case of invasive diarrhoea.* FI-3. The use of diosmectite (Smecta) in combination with another medication.*† FI-4. The use of Saccharomyces boulardii (Ultralevure) in powder form, or in a capsule that has to be opened prior to ingestion, to treat patients with a central venous catheter or an immunodeficiency.* FI-5. Intestinal antiseptics.*† |

FO-1. Oral rehydration solution in the event of diarrhoea.* |

| ENT, pulmonary Problems | |

| G: cough | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| GI-1. Pholcodine.*† GI-2. Mucolytic drugs, mucokinetic drugs or helicidine before 2 years of age.*† GI-3. Alimemazine (Theralene), oxomemazine (Toplexil), promethazine (Phenergan) and other types.*† GI-4. Terpene-based suppositories.*† |

GO-1. Failure to propose a whooping cough booster vaccine for adults who are likely to become parents in the coming months or years (only applicable if the previous vaccination was more than 10 years ago). This booster vaccination should also be proposed to the family of expectant parents and those in contact with them (parents, grandparents, nannies/child minders). |

| H: bronchiolitis in infants | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| HI-1. Beta2 agonists, corticosteroids to treat an infant’s first case of bronchiolitis.* HI-2. H1-antagonists, cough suppressants, mucolytic drugs or ribavirin to treat bronchiolitis.* HI-3. Antibiotics in the absence of signs indicating a bacterial infection (acute otitis media, fever and so on).* |

HO-1. 0.9% NaCl to relieve nasal congestion (not applicable if nasal congestion is already being treated with 3% NaCl delivered by a nebulizer).* HO-2. Palivizumab in the following cases: (1) Babies born both at less than 35 weeks of gestation and less than 6 months prior to the onset of a seasonal RSV epidemic. (2) Children less than 2 years old who have received treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in the past 6 months. (3) Children less than 2 years old suffering from congenital heart disease with haemodynamic abnormalities. |

| I: ENT infections | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| II-1. An antibiotic other than amoxicillin as a first-line treatment for acute otitis media, strep throat or sinusitis (provided that the patient is not allergic to amoxicillin). An effective dose of amoxicillin for an pneumococcal infection is 80–90 mg/kg/day and an effective dose for a streptococcal infection is 50 mg/kg/day.* II-2. Antibiotic treatment for a sore throat, without a positive rapid diagnostic test result, in children more than 3 years old.* II-3. Antibiotics for nasopharyngitis, congestive otitis, sore throat before 3 years of age or laryngitis; antibiotics as a first-line treatment for acute otitis media showing few symptoms after 2 years of age.* II-4. Antibiotics to treat otitis media with effusion (OME), except in the case of hearing loss or if OME lasts for more than 3 months.* II-5. Corticosteroids to treat acute suppurative otitis media, nasopharyngitis or strep throat.* II-6. Nasal or oral decongestant (oxymetazoline (Aturgyl), pseudoephedrine (Sudafed), naphazoline (Derinox), ephedrine (Rhinamide), tuaminoheptane (Rhinofluimicil) and phenylephrine (Humoxal)).*† II-7. H1-antagonists with sedative or atropine-like effects (pheniramine and chlorpheniramine) or camphor; inhalers, nasal sprays or suppositories containing menthol (or any terpene derivatives) before 30 months of age.*† II-8. Ethanolamine tenoate (Rhinotrophyl) and other nasal antiseptics.*† II-9. Ear drops in the case of acute otitis media.* |

IO-1. Doses in mg for drinkable (solutions of) amoxicillin or josamycin.*† IO-2. Paracetamol combined with antibiotic treatment for ear infections to relieve pain.* |

| J: asthma | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| JI-1. Ketotifen and other H1-antagonists, and sodium cromoglycate.* JI-2. Cough suppressants.* |

JO-1. Asthma inhaler appropriate for the child’s age. JO-2. Preventative treatment (inhaled corticosteroids) in the case of persistent asthma.* |

| Dermatological problems | |

| K: acne vulgaris | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| KI-1. Minocycline.*† KI-2. Isotretinoin in combination with a member of the tetracycline family of antibiotics.*† KI-3. The combined use of an oral and a local antibiotic.* KI-4. Oral or local antibiotics as a monotherapy (not in combination with another drug).* KI-5. Cyproterone+ethinylestradiol (Diane 35) as a contraceptive to allow isotretinoin per os.*† KI-6. Androgenic progestins (levonorgestrel, norgestrel, norethisterone, lynestrenol, dienogest, contraceptive implants or vaginal rings).* |

KO-1. Contraception (provided with a logbook/diary) for menstruating girls taking isotretinoin. KO-2. Topical treatment (benzoyl peroxide, retinoids or both) in combination with antibiotic therapy.* |

| L: scabies | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

|

LO-1. A second dose of ivermectin 2 weeks after the first.* LO-2. Decontamination of household linen and clothes and treatment for other family members. |

|

| M: lice | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| MI-1. The use of aerosols for infants, children with asthma or children showing asthma-like symptoms such as dyspnoea. | |

| N: ringworm | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| NI-1. Treatment other than griseofulvin for Microsporum.* |

NO-1. Topical treatment combined with an orally administered treatment.* NO-2. Griseofulvin taken during a meal containing a moderate amount of fat.*† |

| O: impetigo | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| OI-1. The combination of locally applied and orally administered antibiotics.* OI-2. Fewer than two applications per day for topical antibiotics.* OI-3. Any antibiotic other than mupirocin as a first-line treatment (except in cases of hypersensitivity to mupirocin).* |

|

| P: herpes simplex | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| PI-1. Topical agents containing corticosteroids.* PI-2. Topical agents containing acyclovir before 6 years of age.*† |

PO-1. Paracetamol during an outbreak of herpes.* PO-2. Orally administered acyclovir to treat primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.* |

| Q: atopic dermatitis | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| QI-1. A strong topic steroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05% Dermoval, betamethasone dipropionate Diprosone) applied to the face, armpits or groin and to the backside of babies or young children.* More than one application per day of a topical steroid, except in cases of severe lichenification.* QI-2. Local or systemic antihistamine during treatment of outbreaks.* QI-3. Topically applied 0.03% tacrolimus before 2 years of age.*† Topically applied 0.1% tacrolimus before 16 years of age. QI-4. Oral corticosteroids to treat outbreaks.* |

|

| Neuropsychiatric, epilepsy disorders | |

| R: epilepsy | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| RI-1. Carbamazepine, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, pregabalin, tiagabine or vigabatrin in the case of myoclonic epilepsy.* RI-2. Carbamazepine, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, pregabalin, tiagabine or vigabatrin in the case of epilepsy with absence seizures (especially for childhood absence epilepsy or juvenile absence epilepsy).* RI-3. Levetiracetam, oxcarbamazepine in millilitre or in milligram without systematically writing XX mg per Y mL.*† |

|

| S: depression | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| SI-1. An SSRI antidepressant other than fluoxetine as a first-line treatment (in the case of pharmacotherapy).* SI-2. Tricyclic antidepressants to treat depression.* |

|

| T: nocturnal enuresis | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| TI-1. Desmopressin administered by a nasal spray.*† Desmopressin in the case of daytime symptoms. TI-2. An anticholinergic agent used as a monotherapy in the absence of daytime symptoms.* TI-3. Tricyclic agents in combination with anticholinergic agents.*† TI-4. Tricyclic agents as a first-line treatment.* |

|

| U: anorexia | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| UI-1. Cyproheptadine (Periactin) and clonidine.*† | |

| V: attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity | |

| Inappropriate prescriptions | Omissions |

| VI-1. Pharmacological treatment before age 6 years (before school), except in severe cases.* VI-2. Antipsychotic drugs to treat attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity.* VI-3. Slow release methylphenidate as two doses per day, rather than only one dose.*† |

VO-1. Recording a growth chart (height and weight) if the patient is taking methylphenidate.* |

*Criteria analysed in emergency department.

†Criteria analysed in community pharmacy.

ENT: ear, nose and throat.

Our first aim is to assess the prevalence of PIM and PPO detected using POPI in hospital and outpatient care. This is its first application, focusing on prescriptions extracted from the emergency department (ED) and the community pharmacy (CP). Our second objective is to determine the risk factors related to PIM and PPO.

Methods

Population

A retrospective and descriptive study was conducted in the ED of AP-HP Robert-Debré hospital (Paris)—the largest French paediatric hospital—and the Albaret community pharmacy (Seine and Marne). Inclusion criteria included patients who were under 18 years old and who had one or more drug prescriptions between 1 October 2014 and 31 March 2015. Prescription was defined as one or more lines of drugs prescribed by a physician. Exclusion criteria consisted of inaccessible medical records for ED patients and prescription without drugs for outpatients. POPI contains 101 criteria (76 PIMs, 25 PPOs). A literature review was done to obtain criteria. Criteria were categorised according to physiological systems (gastroenterology, respiratory infections, pain, neurology, dermatology and miscellaneous). Criteria were validated by a two-round Delphi consensus technique.37

Data collection

The prescriptions given on leaving hospital ED were extracted from the Urqual software V5 (McKesson Corp, Paris, France). Urqual is an emergency prescription software that is used in many French hospitals. Patient information including age, sex, weight, medical prescription and current diagnosis was collected. Medical histories and clinical examinations were consulted individually when necessary. Due to the significant amount of data, clinical files of the ED were analysed based on primary diagnosis. Prescriptions for secondary diagnosis were not evaluated. For this study, 82/101 criteria were analysed (table 1). Some criteria could not be used for a hospital setting.

The data extracted from Urqual software give only the first drug per prescription for each diagnosis (impossibility to extract all drugs for all prescriptions). To have every medications concerning the primary diagnosis, the prescription was then manually analysed for each diagnosis to evaluate presence of PIM/PPO. Consequently, the number of medications per prescription was not included. However, all prescriptions have been manually reviewed directly from medical files by two authors. For each targeted disorder, the prescription was analysed to detect PIMs or PPOs.

Data from the CP were obtained from the pharmacy management software OPUS (Computer PG, France). Patient’s age and drugs prescribed were collected. Current diagnosis and sex are not available in the OPUS software, so the number of patients per pathology and the number of prescriptions per pathology were lacking. Only drugs that did not require an assessment of diagnosis (eg, domperidone, metoclopramide…) were included (table 1) (28 criteria/101).

Among the five criteria including analgesics and antipyretics, only three were evaluated due to an overwhelming number of prescriptions and their association with many diseases. Pathologies analysed by POPI were the same in ED and in community. Summary of data and inclusion criteria are detailed in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2017-019186supp001.pdf (178.5KB, pdf)

We consulted the software used by the ED by searching either: (1) per drug and by therapeutic class extension and (2) by main diagnosis for which a POPI item could matched. In each case, data were collected regardless of whether there was a PIM/PPO.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as continuous variables (age, number of prescriptions by patient and number of medications per prescription) and were presented as median and IQR (25th–75th percentiles) or mean (SD), minimum and maximum depending on normal distribution.

Mixed effects logistic regression modelling for repeated measurements was applied to identify factors associated with PIM and PPO (yes/no) in the hospital and community settings. Unit of analysis was ‘the prescription’.

Univariate models were performed using different candidate factors as:

For model performed with hospital data: sex and age (0 days–2 years, 2–6 years, 6–12 years and 12–18 years).

For model performed with community data: age (0 days–2 years, 2–6 years, 6–12 years and 12–18 years) and number of medications (drugs) per prescription.

The model was constructed using the parameters of the univariate analysis, which showed at least a trend towards significance, with a cut-off of p=0.2. ORs with 95% CIs were estimated. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05. SPSS V.22 software and SAS V.9.4 were used for analysis.

Patient and public involvement

No patient and public involvement.

Results

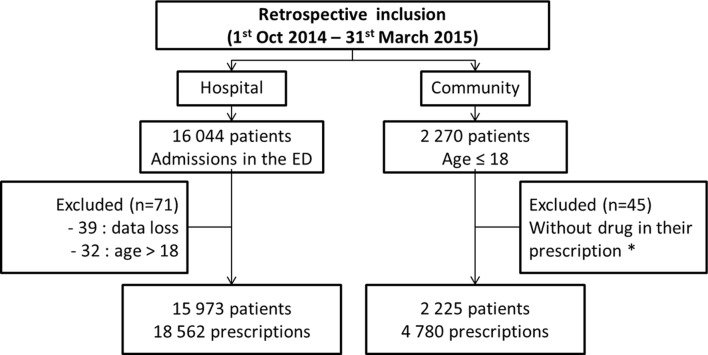

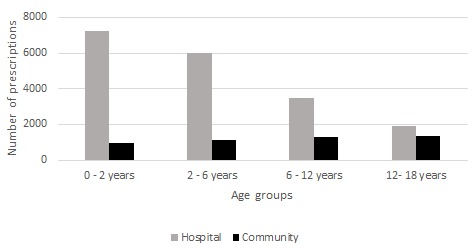

In the ED, 18 562 prescriptions for 15 973 patients were analysed. Around 11 500 prescriptions were reviewed manually concerning 9500 patients. Among the patients, 29% had at least two visits in 6 months. In the CP, 4780 prescriptions for 2225 patients were evaluated (figure 1). In ED and CP, 53% of patients had been issued one prescription, 21% with two and 26% with three or more prescriptions. The population’s characteristics and the frequency of pathologies were presented in table 2. Distribution of number of prescriptions by age category was described in the figure 2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart indicating the course of the study. *Prescriptions with only one medical device, dietary supplement or hygiene product. ED, emergency department.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population

| Population characteristics | Hospital (n=15 973) |

Community (n=2 225) |

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 4.9 (4.5) | 7.9 (5.3) |

| Min - max | 0–18 | 0–18 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 8769 (54.9) | NA |

| Number of prescriptions/patient mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.9) |

| Min - max | 1–12 | 1–16 |

| Number of drugs per prescription mean (SD) | NA | 2.4 (1.6) |

| Min - max | 1–22 | |

| Number of prescriptions by pathology, n (%) | ||

| Digestive disorders | 2728 (14.7) | NA |

| ENT-Pulmonary disorders | 8397 (45.2) | NA |

| Dermatological disorders | 604 (3.3) | NA |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | 242 (1.3) | NA |

| Other illnesses’* | 6591 (35.5) | NA |

*For example, traumatic injury, pain and sickle cell disease.

ENT, ear, nose and throat; NA, not available.

Figure 2.

Distribution of number of prescriptions according to age category in hospital and community settings.

In the hospital, POPI identified 541 PIMs in 2.9% of the prescriptions analysed. They were detected in 3.3% of the patients (n=530). PPOs were detected in 2.3% of prescriptions for 2.7% of patients. In the community, PIMs and PPOs represented 12.3% and 6.1% of all prescriptions, affecting 26.4% and 11.3% patients, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) and potential prescription omissions (PPOs) identified by POPI

| Hospital N (%) |

Community N (%) |

|

| Number of prescriptions (N) | 18 562 | 4780 |

| PIMs identified per prescription | ||

| 1 | 519 (2.8) | 551 (11.5) |

| 2 | 11 (0.1) | 37 (0.8) |

| Prescriptions with at least one PIM | 530 (2.9) | 588 (12.3) |

| PPOs identified per prescription | ||

| 1 | 424 (2.3) | 293 (6.1) |

| Number of patients (N) | 15 793 | 2225 |

| Patients with at least one PIM | 530 (3.3) | 588 (26.4) |

| Patients with at least one PPO | 424 (2.7) | 251 (11.3) |

POPI, Pediatrics: Omission of Prescription and Inappropriate prescription.

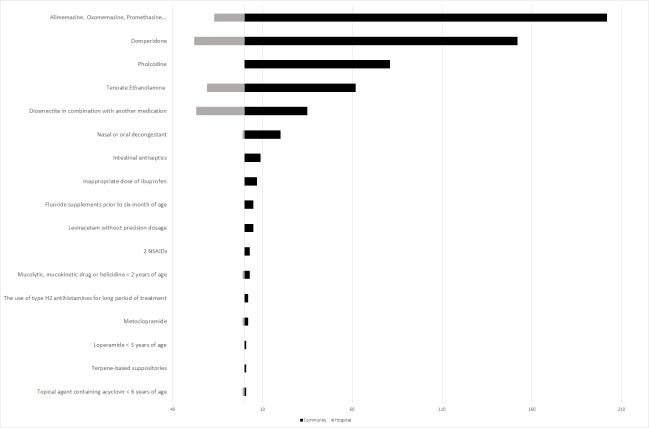

Table 4 presents the prevalence of PIMs (or PPOs) in the ED in patients with the targeted disorders. Patients with the targeted disorders represent the individuals who were at risk of each PIM/PPO. Table 5, however, presents the PIMs (or PPOs) as a proportion of the total number of PIMs (or PPOs) in the CP. Respiratory and digestive diseases had the highest rate of PIM in hospital and CP. For various illnesses, we removed one criterion involving medicines containing codeine because of their new contraindication in children under 12 years old.38 However, the prescription of codeine was observed in 18 cases. According to our comparison of PIMs detectable in both settings, out-of-hospital medication always presents with higher prevalence of PIMs (figure 3).

Table 4.

Prevalence of PIMs and PPOs identified by POPI in hospital

| Criteria | No. of PIMs | No. of patients with the targeted disorders* | % of PIMs in patients with the targeted disorders | |

| PIMs | 541 | 7304 | 7.4% | |

| Various illnesses | 3 | 64 | 4.6% | |

| AI-6 | Opiates to treat migraine attacks | 3 | 64 | 4.6% |

| Digestive disorders | 56 | 1956 | 2.8% | |

| EI-2 | Domperidone | 28 | 1956 | 1.4% |

| FI-3 | The use of diosmectite (Smecta) in combination with another medication. | 27 | 1956 | 1.4% |

| EI-1 | Metoclopramide | 1 | 1956 | <0.1% |

| ENT-Pulmonary disorders | 472 | 5163 | 9.1% | |

| II-4 | Antibiotics to treat acute suppurative otitis media and so on. | 2 | 7 | 28.6% |

| II-2 | Antibiotic treatment for a sore throat, without a positive RDT. | 23 | 160 | 14.4% |

| II-9 | Ear drops in the event of acute otitis media. | 86 | 1083 | 7.9% |

| HI-1 | Beta2 agonist, corticosteroids to treat an infant’s first case of bronchiolitis. | 25 | 386 | 6.4% |

| II-5 | Corticosteroids to treat acute suppurative otitis media and so on. | 190 | 3616 | 5.2% |

| II-1 | An antibiotic other than amoxicillin as a first-line treatment. | 59 | 1259 | 4.7% |

| JI-1 | H1-antagonist to treat asthma. | 9 | 802 | 1.1% |

| II-8 | Tenoate etanolamine (Rhinotrophyl) and other nasal antiseptics. | 21 | 2455 | 0.8% |

| II-3 | Antibiotics for nasopharyngitis. | 26 | 3444 | 0.7% |

| GI-3 | Alimemazine (Theralene), oxomemezine (Toplexil) and so on. | 18 | 2585 | 0.7% |

| JI-2 | Cough suppressants to treat asthma. | 5 | 802 | 0.6% |

| HI-2 | H1-antagonists, cough suppressants and so on to treat bronchiolitis. | 2 | 386 | 0.5% |

| II-7 | H1-antagonists with sedative or atropine-like effects. | 4 | 2585 | 0.2% |

| GI-2 | Mucolytics drugs, mucokinetics drugs or helicidine before 2 years of age. | 1 | 2585 | <0.1% |

| II-6 | Nasal or oral decongestant and so on. | 1 | 2455 | <0.1% |

| Dermatological disorders | 10 | 100 | 10% | |

| OI-1 | A combination of locally applied and orally administered antibiotics. | 9 | 32 | 28.1% |

| PI-2 | Topical agents containing acyclovir administered to a child under 6 years of age. | 1 | 68 | 1.5% |

| No. of PPO | No. of patients with the targeted disorders* | % of PPOs in patients with the targeted disorders | ||

| PPOs | 424 | 4508 | 9.4% | |

| Digestive disorders | 372 | 1956 | 19.0% | |

| EO-1 | Oral rehydration solution in the event of vomiting. | 135 | 313 | 43.1% |

| FO-1 | Oral rehydration solution in the event of diarrhoea. | 237 | 1643 | 14.4% |

| ENT-Pulmonary disorders | 51 | 1469 | 3.5% | |

| HO-1 | 0.9% NaCl to relieve nasal congestion and so on. | 38 | 386 | 9.8% |

| IO-2 | Acetaminophen combined with antibiotic treatment for ear infections and so on. | 13 | 1083 | 1.3% |

| Dermatological disorders | 1 | 3 | 33.3% | |

| NO-2 | Griseofulvin taken during a meal containing a moderate amount of fat. | 1 | 3 | 33.3% |

*The number of patients with the targeted disorder corresponds to patients with clinical situations at risk of PIM or PPO.

%, Percentage calculated by the number of PIMs or PPO detected from the total number of analyzable cases; ENT, ear, nose and throat; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medicines; PPOs, potentially prescribing omissions; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

Table 5.

Most frequently occurring PIMs and PPOs identified by POPI in community setting

| Criteria | Proportion of PIMs per disorder according to total number of PIMs or PPOs, N (%) |

| Total number of PIMs, n=625 | |

| Various illnesses | 15 (2.4) |

| AI-5: oral solutions of ibuprofen administered in more than 3 doses and so on. | 7 (1.1) |

| CI-1: fluoride supplements prescribed to infants under 6 of age. | 5 (0.8) |

| AI-4: the combined use of two NSAIDs | 3 (0.5) |

| Digestive disorders | 201 (32.2) |

| EI-2: domperidone | 152 (24.3) |

| FI-3: the use of diosmectite (Smecta) in combination with another medication. | 35 (5.6) |

| FI-5: intestinal antiseptics. | 9 (1.5) |

| EI-1: metoclopramide | 2 (0.3) |

| EI-6: the use of type H2 antihistamines for long periods of treatment. | 2 (0.3) |

| FI-1: loperamide before 3 years of age. | 1 (0.2) |

| ENT-Pulmonary disorders | 403 (64.4) |

| GI-3: alimemazine (Theralene), oxomemazine (Toplexil) and so on. | 202 (32.2) |

| GI-1: pholcodine | 81 (13.0) |

| II-8: etanolamine tenoate (Rhinotrophyl) and other nasal antiseptics. | 96 (15.3) |

| II-6: nasal or oral decongestant and so on. | 20 (3.2) |

| GI-2: mucolytic drugs, mucokinetic drugs or helicidine prescribed to a child under 2 years of age. | 3 (0.5) |

| GI-4: terpene-based suppositories. | 1 (0.2) |

| Dermatological disorders | 1 (0.2) |

| PI-2: topical agents containing acyclovir prescribed to a child under 6 years of age. | 1 (0.2) |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | 5 (0.8) |

| RI-3: levetiracetam in millilitre or in milligram prescribed without systematically indicating XX mg per Y mL. | 5 (0.8) |

| Proportion of PPOs per disorder according to total number of PIMs or PPOs, N (%) | |

| PPOs, n = 293 | |

| ENT infections | |

| IO-1: dose in milligram for oral (solution of) amoxicillin and so on, N (%) | 293 (100) |

%, percentage of PIMs or PPOs calculated from the total number of PIMs or PPO detected; ENT, ear, nose and throat; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medicines; POPI, Pediatrics: Omission of Prescription and Inappropriate prescription; PPOs, potentially prescribing omissions.

Figure 3.

Comparison of PIMs detected in hospital and in outpatient care. NSAID, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatoy drug; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medicines.

The analysis of criterion regarding the prescription of amoxicillin in milligram (IO-1) was not possible due to the fact that this drug is prescribed in great quantity. Among 100 prescriptions randomly assessed in hospital extractions, 97 prescriptions were inappropriate. Nonetheless, one analysis on acute otitis media alone identified a rate of 99.5% (807/811) of prescriptions issued without specification of the doses in milligram for oral amoxicillin. In community care, this was observed in 97% of prescriptions, in 13.2% of patients (table 5).

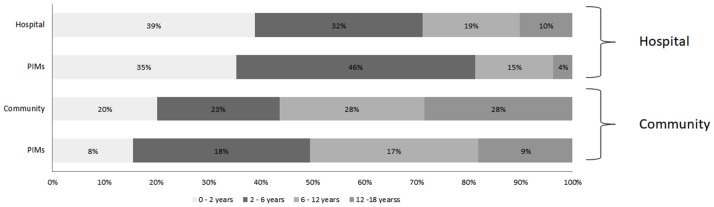

PIMs classed by age are presented in the figure 4. Potential factors associated with PIM or PPO are presented in online supplementary appendix 2a, b. On univariate analysis, only age was associated with risk of PIM or PPO in hospital setting. In a community setting, the number of drugs per prescription and different age categories were found to be significantly associated with a higher risk of PIM or PPO on univariate analysis. With a multivariable logistic regression model, the same results were obtained.

Figure 4.

Total prescription and PIMs in both hospital and outpatient care: percentage distribution by age group. PIMs, potentially inappropriate medicines.

bmjopen-2017-019186supp002.pdf (44.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first study to observe the prevalence of PIMs and PPOs in a paediatric population. In the literature, such tools focused on detecting PIMs/PPOs in a geriatric population.22 23 39 40 The two populations are not comparable. Respiratory and digestive pathologies are typical in children and are not so in geriatric populations, which are more concerned by cardiovascular and nervous central system diseases.22 23 41

Domperidone was frequently prescribed in a community setting, yet this drug is responsible for cardiac adverse effects such as QT prolongation. This side effect is described in the literature in adult populations and paediatric populations. The detection of this prescription will enable us to avoid cardiac risks.42–47

Prevalence of beta2 agonists or corticosteroids in an infant’s first case of bronchiolitis is 6.4% (25/386 cases), lower than that observed in a study of another French area in 2012 (41%).48–50 The use of beta2 agonists in a first case of bronchiolitis has no impact on oxygen saturation, length of hospitalisation or length of illness. They concurrently cause side effects as tachycardia, oxygen saturation and tremors.51 Implementation of guidelines has permitted to decrease beta2 agonist and corticosteroid use in a French hospital without increase morbidity.52

Unnecessary exposure to cough suppressants, pholcodine, nasal or oral decongestants was also observed frequently in this sector.53 In Norway, all drugs containing pholcodine were refused marketing authorisation in March 2007. As of this date, a decrease in sensitisation to suxamethonium used in anaesthesia and a decrease of 30%–40% cases of anaphylaxis was identified.54

Our tool enabled us to detect rare PIMs that carry heavy consequences, such as opioid use for migraines. The use of opioids for this disease induces a transition from episodic to chronic headaches and an increase of sensitivity to pain.55–57

Overuse of medication, in particular opioids, could contribute to the chronicity of headaches in 20%–30% of children and adolescents with chronic daily headaches.57

In the management of diarrhoea caused by gastroenteritis in hospitals, our study found that it was common to omit to prescribe oral rehydration solution (ORS): 14% (237/1643 cases). Even so, this rate is lower than that found in another national study in 2007 (29%).58 However, ORSs prevent hospitalisation in cases of acute gastroenteritis. In the UK, the use of ORSs has enabled a decrease from 300 deaths/year in 1970s to 25 deaths/year in 1980s.59 60 The need for ORS prescriptions was confirmed by the recommendation of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition in 2014.61

As estimated, children aged between 0 years and 12 years have the highest risk of presenting with a PIM, according to a multivariate analysis. No PIMs or PPOs were detected for patients aged less than 28 days. As we know, they are also affected by off-label drug prescriptions, which is consistent with reports from other sources.62 63 As with geriatrics, an increase in the number of medications used can be associated with PIM.23 Prescriptions issued from hospitals elicit fewer PIMs than those issued by the community. The main reason for this is that many drugs are not available in our hospital, such as cough suppressants, Rhinotrophyl (tenoate ethanolamine), domperidone and so on. This shows that many PIMs are preventable in a hospital settings. An efficient method for the prevention of PIM could be to focus on the prescribing habits of physicians and thus have an impact on the selection of drugs, thereby reducing the rate of PIM.

The data were extracted from a CP and the ED of a mother–child hospital during the winter months. The data focus on winter epidemics. An analysis of the year in its entirety would have found other PMIs/PPOs concerning different pathologies or events related to travel. While the Robert-Debré hospital offers subspecialised hospitalisation services (cardiology, nephrology, haematology and so on), the ED drains the more general activity. Likewise, the data coming from the CP provide a representative image of the paediatric prescriptions that could be found in other French pharmacies. Concerning a generalisation of our data to other countries, a study is in progress to specify which POPI items could be applicable internationally.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective and monocentric study; the result in hospital could be underestimated. In addition, several criteria could not be analysed due to the large number of prescriptions (eg, those for fever or pain that are associated with many diseases) or absence of certain pathologies (mosquitos, lice, hyperactivity and so on). All drugs were not evaluated. Antibiotic prophylaxis, vitamin supplements, propositions for vaccination and so on can only be analysed in prospective studies. The lack of clinical information is the main limitation in detection in a community setting. This also constitutes a challenge for pharmaceutical care review in elderly patients.64 However, a certain amount of PIM was identified using POPI. Our study showed that there are many criteria that are easily identifiable and that could be detected without accessing clinical information. Moreover, community pharmacists, in their practice, can extrapolate diagnoses from their experience, from common indications or by interviewing their patients. The study presents a limitation regarding the URQUAL software, from which the number of medications per prescription could not be extracted.

This is the first study that permits an evaluation of the prevalence of PIM and PPO in paediatrics prescription. The detection of PIMs/PPOs would improve patient care and prevent hospitalisation and ADRs. A stepped wedge randomised cluster multicentre study will be conducted to prove if POPI decreases number of PIM and PPO. It is also necessary to evaluate the impact of this tool on reducing adverse drugs events, both in consultation or hospitalisation. The impact of pharmacists in providing appropriate prescriptions should be also evaluated. Subsequently, this tool may be offered to several professional societies such as the French Society for Pediatricians and the French Society of Clinical Pharmacy to make its use more widespread. The tool should be regularly updated to reflect recent events and to specify certain criteria.

To facilitate its use, this tool can be presented as a mobile app, a small handbook or installed into prescription software. In summary, we hope that POPI could be a practical option used to reduce medication errors and to improve the suitability of prescriptions. It provides rapid detection of PIM and PPO and can also open up discussion on the relationship between doctor and pharmacist to remedy the issues at hand.65

Conclusion

Our study was carried out in in two sectors, hospital and community, and provides a global view of PIM and PPO in paediatric patients. POPI has a clinical impact and plays a role in improving prescription quality in various sectors and patient care. POPI should be applied in different services to deepen and reinforce its utilisation. A prospective and multicentre study should be conducted to evaluate its impact and benefit in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Emergency Department of Robert-Debré Hospital and the Albaret Pharmacy community for their data support. We would also like to thank the French Society of Clinical Pharmacy (paediatric group) for their support.

Footnotes

Contributors: SP-L and AB-A conceptualised and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. RB and PKHN carried out analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. XB, TW and OB reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. FA and PA supplied data from hospital and community pharmacy and reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This project was approved by the local research ethics committee (n°2015/218).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We have no additional unpublished data.

References

- 1. Lund BC, Carnahan RM, Egge JA, et al. Inappropriate prescribing predicts adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:957–63. 10.1345/aph.1M657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chrischilles EA, VanGilder R, Wright K, et al. Inappropriate medication use as a risk factor for self-reported adverse drug effects in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1000–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995;274:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 2001;285:2114–20. 10.1001/jama.285.16.2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician’s guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:795–801. 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clavenna A, Bonati M. Differences in antibiotic prescribing in paediatric outpatients. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:590–5. 10.1136/adc.2010.183541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Impicciatore P, Choonara I, Clarkson A, et al. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in paediatric in/out-patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:77–83. 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01407.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. dos Santos DB, Coelho HL. Adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children in Fortaleza, Brazil. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:635–40. 10.1002/pds.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rashed AN, Wong IC, Cranswick N, et al. Risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions in hospitalised children: international multicentre study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:801–10. 10.1007/s00228-011-1183-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thiesen S, Conroy EJ, Bellis JR, et al. Incidence, characteristics and risk factors of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children - a prospective observational cohort study of 6,601 admissions. BMC Med 2013;11:237 10.1186/1741-7015-11-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vries TW, van Hunsel F. Adverse drug reactions of systemic antihistamines in children in the Netherlands. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:968–70. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aljebab F, Choonara I, Conroy S. Systematic review of the toxicity of short-course oral corticosteroids in children. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:365–70. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cliff-Eribo KO, Sammons H, Choonara I. Systematic review of paediatric studies of adverse drug reactions from pharmacovigilance databases. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:1321–8. 10.1080/14740338.2016.1221921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reidenberg MM. Can the selection and use of essential medicines decrease inappropriate drug use? Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85:581–3. 10.1038/clpt.2009.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, et al. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment) an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing 2007;36:632–8. 10.1093/ageing/afm118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. others LS; Consommation médicamenteuse chez le sujet âgé. Consommation, prescription, iatrogénie et observance. 2005. http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/pmsa_synth_biblio_2006_08_28__16_44_51_580.pdf.

- 17. Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, et al. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naugler CT, Brymer C, Stolee P, et al. Development and validation of an improving prescribing in the elderly tool. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2000;7:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:891–6. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laroche M-L, Bouthier F, Merle L, et al. Médicaments potentiellement inappropriés aux personnes âgées : intérêt d’une liste adaptée à la pratique médicale française. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2009;30:592–601. 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, et al. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;46:72–83. 10.5414/CPP46072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers' criteria. Age Ageing 2008;37:673–9. 10.1093/ageing/afn197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gallagher P, Lang PO, Cherubini A, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67:1175–88. 10.1007/s00228-011-1061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dalleur O, Boland B, Losseau C, et al. Reduction of potentially inappropriate medications using the STOPP criteria in frail older inpatients: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging 2014;31:291–8. 10.1007/s40266-014-0157-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan C, O’Mahony D, Kennedy J, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish elderly population in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:936–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03531.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yayla ME, Bilge U, Binen E, et al. The use of START/STOPP criteria for elderly patients in primary care. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:1–4. 10.1155/2013/165873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borges EP, Morgado M, Macedo AF. Prescribing omissions in elderly patients admitted to a stroke unit: descriptive study using START criteria. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:481–9. 10.1007/s11096-012-9635-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, et al. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)--an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing 2007;36:632–8. 10.1093/ageing/afm118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, et al. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:562–70. 10.1016/S1543-5946(10)80005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lau DT, Kasper JD, Potter DE, et al. Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:68–74. 10.1001/archinte.165.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hébert G, Prot-Labarthe S, Tremblay M-E, et al. La pédiatrie. toujours exclue de l’innovation pharmaceutique ? Arch Pédiatrie 2014;21:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Benavides S, Huynh D, Morgan J, et al. Approach to the pediatric prescription in a community pharmacy. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther JPPT Off J PPAG 2011;16:298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mercier J, Morin L, Prot-Labarthe S. Les erreurs de prescription et leurs conséquences, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Risk R, Naismith H, Burnett A, et al. Rational prescribing in paediatrics in a resource-limited setting. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:503–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choonara I. Rational prescribing is important in all settings. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:720 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prot-Labarthe S, Vercheval C, Angoulvant F, et al. «POPI; pédiatrie: omissions et prescriptions inappropriées». Outil d’identification des prescriptions inappropriées chez l’enfant. Archives de Pédiatrie 2011;18:1231–2. 10.1016/j.arcped.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prot-Labarthe S, Weil T, Angoulvant F, et al. POPI (Pediatrics: Omission of Prescriptions and Inappropriate prescriptions): development of a tool to identify inappropriate prescribing. PLoS One 2014;9:e101171 10.1371/journal.pone.0101171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. European Medicines Agency. Codeine not to be used in children below 12 years for cough and cold. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu.

- 39. Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1531–6. 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440350031003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44:213–8. 10.1093/ageing/afu145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Caillère N, Caserio-Schonemann C, Oscour® R. (Organisation de la surveillance coordonnée des urgences) Résultats nationaux 2004/2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rocha CM, Barbosa MM. QT interval prolongation associated with the oral use of domperidone in an infant. Pediatr Cardiol 2005;26:720–3. 10.1007/s00246-004-0922-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rossi M, Giorgi G. Domperidone and long QT syndrome. Curr Drug Saf 2010;5:257–62. 10.2174/157488610791698334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Djeddi D, Kongolo G, Lefaix C, et al. Effect of domperidone on QT interval in neonates. J Pediatr 2008;153:663–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Domperidone: QT prolongation in infants. Prescrire Int 2011;20:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caraballo L, Molina G, Weitz D, et al. Proarrhythmic effects of domperidone in infants: a systematic review]. Farm Hosp Organo Of Expresion Cient Soc Espanola Farm Hosp 2014;38:438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rochoy M, Auffret M, Béné J, et al. [Antiemetics and cardiac effects potentially linked to prolongation of the QT interval: Case/non-case analysis in the national pharmacovigilance database]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2017;65:1–8. 10.1016/j.respe.2016.06.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Branchereau E, Branger B, Launay E, et al. Management of bronchiolitis in general practice and determinants of treatment being discordant with guidelines of the HAS]. Arch Pédiatrie Organe Off Sociéte Fr Pédiatrie 2013;20:1369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bronchiolitis in children | 1-recommendations | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG9/chapter/1-recommendations (accessed 22 Jun 2015).

- 50. Conférence de Consensus sur la prise en charge de la bronchiolite du nourrisson. 2000. http://www.has-sante.fr.

- 51. Gadomski AM, Scribani MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD001266 CD001266. doi 10.1002/14651858.CD001266.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Prescrire La Revue. http://www.prescrire.org/fr/ 2014

- 53. de Pater GH, Florvaag E, Johansson SG, et al. Six years without pholcodine; Norwegians are significantly less IgE-sensitized and clinically more tolerant to neuromuscular blocking agents. Allergy 2017;72:813–9. 10.1111/all.13081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Loder E, Weizenbaum E, Frishberg B, et al. Choosing wisely in headache medicine: the American Headache Society’s list of five things physicians and patients should question. Headache 2013;53:1651–9. 10.1111/head.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Casucci G, Cevoli S. Controversies in migraine treatment: opioids should be avoided. Neurol Sci 2013;34 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S125–8. 10.1007/s10072-013-1395-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine. Pain 2009;142:179–82. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Piazza F, Chiappedi M, Maffioletti E, et al. Medication overuse headache in school-aged children: more common than expected? Headache 2012;52:1506–10. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martinot A, Pruvost I, Aurel M, et al. [Improvement in the management of acute diarrhoea in France?]. Arch Pediatr 2007;14 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Walker-Smith JA. Management of infantile gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child 1990;65:917–8. 10.1136/adc.65.9.917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murphy MS. Guidelines for managing acute gastroenteritis based on a systematic review of published research. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:279–84. 10.1136/adc.79.3.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: update 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;59:132–52. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Joret P, Prot-Labarthe S, Brion F, et al. Caractérisation des indications hors AMM en pédiatrie: analyse descriptive de 327 lignes de prescriptions dans un hôpital pédiatrique. Pharm Hosp Clin 2014;49:e151–2. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shah SS, Hall M, Goodman DM, et al. Off-label drug use in hospitalized children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:282–90. 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ryan C, O’Mahony D, O’Donovan DÓ, et al. A comparison of the application of STOPP/START to patients’ drug lists with and without clinical information. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:230–5. 10.1007/s11096-012-9733-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, et al. Effects of Pharmacists’ Interventions on Appropriateness of Prescribing and Evaluation of the Instruments’ (MAI, STOPP and STARTs’) Ability to Predict Hospitalization–Analyses from a Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e62401 10.1371/journal.pone.0062401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019186supp001.pdf (178.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019186supp002.pdf (44.3KB, pdf)