Abstract

Objective

Timely access to care and continuity with a specific provider are important determinants of patient satisfaction when booking appointments in primary care settings. Advanced access booking systems restrict the majority of providers’ appointment spots for same-day appointments and keep the number of prebooked appointments to a minimum. In the teaching clinic environment, continuity with the same provider can be a challenge. This study examines trade-offs that patients may consider during appointment bookings for six different clinical scenarios across a number of key access and continuity attributes using a discrete choice experiment (DCE) method.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Two urban family medicine teaching clinics in Canada.

Participants

Convenience sample of 430 patients of family medicine clinics aged 18 and older.

Intervention

Discrete choice conjoint experiment survey.

Primary outcome measures

Patient preferences on six attributes: appointment booking method, appointment wait time, time spent in the waiting room, appointment time convenience, familiarity with healthcare provider and position of healthcare provider. Data were analysed by hierarchical Bayes analysis to determine estimates of part-worth utilities for each respondent.

Results

Patients rated appointment wait time as the most highly valued attribute, followed by position of provider, then familiarity with the provider. Patients showed a significant preference (p<0.02) for their own physician for booking of routine annual check-ups and other logical preferences across attributes overall and by clinical scenario.

Conclusions

Patients preferred timely access to their primary care team over other attributes in the majority of health state scenarios tested, especially urgent issues, however they were willing to wait for a check-up. These results support the notion that advanced access booking systems which leave the majority of appointment spots for same day access and still leave a few for continuity (check-up) bookings, align well with trends in patient preferences.

Keywords: patient preference, family practice, choice behavior, appointments and schedules, surveys and questionnaires

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study designed a discrete choice experiment with input from stakeholders about attributes that were important in their context.

The study was conducted in two clinics that are part of an academic family medicine department and results may not be applicable in other jurisdictions.

The study participants were a convenience sample of patients who may have been frequent visitors to the practice and their views may not represent all patients.

Background

Improving the patient experience in outpatient primary care settings is an important priority for health policy advisors and healthcare providers.1–4 When patients contact primary care clinics for appointments, how many days or weeks must they wait for their appointments? Will they see providers they know best when they are finally seen? How long must they wait in reception areas and will the appointments be offered at times that are convenient for them? Most importantly, which attributes of that scheduling/consultation process are priorities for patients and which are they willing to trade-off in order to have a satisfactory experience in booking and attending that appointment?

This study was designed to gain deeper understanding of the relative value that patients place on various attributes connected to each attempt to access their primary care providers. We used the discrete choice experiment (DCE) method that has been used extensively in healthcare research.5–12 In this method, respondents are presented with a questionnaire with varying combinations of different attributes of a decision, for example, treatment or procedure, and for each combination, asked to choose which of the options they prefer. Patients’ preferences as expressed by part-worth utilities (PWUs) are estimated for each decision attribute. The importance of each attribute is estimated and the PWUs used in simulations to better understand patients’ preferences for and trade-offs among complete configurations of the treatment.

Speed of access and continuity with the same clinician are commonly studied attributes in various clinical scenarios and while both are often identified as key priorities for patients they are also attributes that are often in conflict with each other in real world clinical practice. The interplay between access and continuity may be complicated even more in primary care settings that have interprofessional teams or in academic clinics where patients may be expected to see different types of clinicians (eg, nurse vs doctor vs resident physicians). Patients often must decide whether to take the appointment offered today if it means having to see a provider other than their family physician. Will that decision change based on the health reason that prompts the appointment request?

By gaining a better understanding of patient preferences in various health states, clinical teams will be better positioned to design health systems in ways that are truly patient-centred. Advanced access scheduling systems are an example of a redesign strategy used in many primary care settings to reduce wait times and improve access to clinicians by limiting the proportion of prebooked appointments and opening up time for same or next-day appointments.10 Advanced access booking has been adopted by many primary care clinics around the world and its value has been evaluated and generally found to be positive.11–15

This study uses DCE in an interprofessional academic setting to evaluate patients’ preferences for six attributes of access to their family practice clinic including health provider (family physician, resident physician or allied health professionals), familiarity with the provider, method of booking (telephone vs online) and wait times across different clinical scenarios.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey with family practice patients, using a DCE method that we developed through literature review and focus groups with stakeholders.

Questionnaire development

The core of the questionnaire was composed of a DCE. DCEs are used regularly and increasingly to study the preferences of patients and physicians for health services and products as well as preferences of consumers in general. Health applications include in-hospital patient care,16 colorectal cancer17 and usage of pharmaceuticals.18 International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidelines19 were followed for the design, execution, analysis and interpretations of the DCE.

An initial set of continuity and access attributes was derived from the literature. To refine the attributes for relevance to the study setting, a focus group discussion was held at each participating clinic. Each group included a nurse, receptionist, a resident and a staff physician who had been involved with implementing advanced access booking. We described the purpose of the discussion as assisting with the creation of the survey instrument for a survey of patients of these clinics, and that participation was voluntary. We provided scenarios to practice team members in the focus group, to stimulate discussion about attributes. The scenarios reflected access attributes from the literature and that the research team felt were relevant to primary care: speed of appointment, appointment with regular clinician who knows the patient, type of provider (physician, nurse, resident). These attributes were validated by the focus group as very important to include. Participants also suggested an attribute relating to number of phone calls needed to reach the practice for an appointment which was felt to be a lower priority and not included in the DCE. We next described four scenarios that might affect patients’ access preferences (new minor symptom, new urgent symptom, anxiety issues, routine check-up) and asked for input on these and for additional scenarios that would be relevant in the context of a family practice teaching centre. The additional level of online booking was added to the appointment booking method attribute, and for type of provider, the levels of family doctor, training doctor (resident) and nurse/nurse practitioner were recommended. The wording of attribute levels was also refined through discussions and expert judgement of the research team (including two physicians involved in implementing open access) (table 1).

Table 1.

Attributes and levels that comprised the discrete choice experiment

| Attribute | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| I can book an appointment | On the internet, right now | Over the phone, and wait less than 1 min | Over the phone, and wait 1 to 10 min until it is answered |

| I get to see a healthcare provider | On the same day | In 1–14 days | In more than 14 days |

| I will spend ___ minutes in the waiting room | Less than 15 | Between 15 and 30 | More than 30 |

| The appointment time is | Exactly the time of day I want | Not exactly the time of day I want, but okay | Not a good time at all |

| I will see a healthcare provider who knows me | Well | Not very well | Not at all |

| The healthcare provider is a | Family doctor | Training doctor (resident) | Nurse/nurse practitioner |

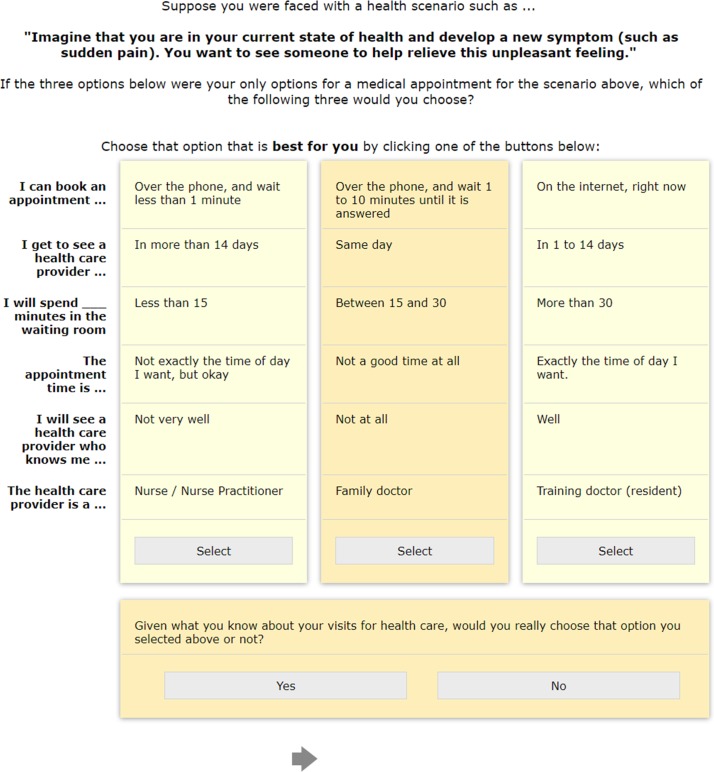

The fractional factorial random experiment was designed using Sawtooth Software SSI Web V.7.0.26, as was the whole questionnaire. Each respondent saw a series of 10 randomly designed choice sets, each of which provided three alternative configurations of a possible scenario of waiting times and appointment encounters. Two fixed tasks were added to test internal reliability. A representative choice task is provided in figure 1. The questionnaire began with questions about frequency of visits to the clinic usual provider seen and self-reported health status, and ended with demographic questions after the choice sets. The questionnaire was pilot tested for clarity and time-to-complete with four staff members of the research team not familiar with the project. Minor wording changes were made. The DCE was introduced and explained to respondents prior to the first choice question.

Figure 1.

Example of a choice task given to participants in the questionnaire.

We hypothesised that patients’ preferences for appointment arrangements would be related to the nature and urgency of health states for those appointments.20 Based on literature review and our focus groups, we defined six states that may motivate requests for consultations with primary healthcare providers. For example, we hypothesised that patients would be relatively less motivated to press for quick appointments if they were seeking routine check-ups and more highly motivated if they experienced sudden pain or if a child were sick.

A random 1/6 of the sample was presented with each of these health states and asked to answer all of the DCE choice questions as if they were in that state.

The six health scenarios varied in the DCE were:

Imagine that you are in your current state of health and develop a new symptom (such as a cold). You are pretty sure you know what it is, and you want some medication for it.

Imagine that you are in your current state of health and develop a new symptom (such as unexpected blood in stools). You are not sure what the symptom means, and you want to consult someone to find out.

Imagine that you are in your current state of health and develop a new symptom (such as sudden pain). You want to see someone to help relieve this unpleasant feeling.

Imagine that you are in your current state of health and are experiencing recurring increased anxiety due to work or family related issues. You want to see someone to talk about these changes and how your health may be affected.

Imagine that you are in your current state of health. You are due for a routine check-up or follow-up (such as appointments for a chronic condition or a physical exam).

Imagine that your child or another family member is sick. You would like to book an appointment for them to see a healthcare provider.

For a DCE study, a sample size of 300–500 subjects is generally considered adequate and Johnson’s often-used rule-of-thumb calculates a sample of 100 for a DCE having our design specifications.21

Survey participants

A convenience sample of patients was recruited in 2012 from two interprofessional family practice teaching clinics with which the researchers are affiliated, in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. One clinic serves approximately 17 000 patients and the other 12 000. The clinics are staffed by family physicians (n=30), family medicine residents (n=70), nurse practitioners (n=10), mental health therapists (n=6), pharmacists (n=3), occupational therapists (n=2) and dieticians (n=2).

Patients aged 18 years or older and able to read English well enough to complete the questionnaire were eligible. English proficiency was not formally assessed prior to initiation of the survey.

The questionnaire was created electronically (web-based) and self-administered via computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). Recruitment was done by a research assistant who approached patients in the waiting room (clinic A, n=53) while waiting to see their healthcare providers, and through emails to patients who had email addresses on file (clinic B, n=377). The research assistant initiated the CAPI questionnaire on her laptop for patients recruited in the waiting room of clinic A and was available for questions.

Statistical methods

The experiment was created within Sawtooth Software SSI Web as a randomised fractional factorial design. The choice data were analysed using hierarchical Bayes estimation (HB) within Sawtooth Software CBC/HB for the sample overall.

Aggregate-level multinomial logit (MNL) analysis was executed to provide initial-level analysis of the choice data as was a basic count-analysis. HB of preference coefficients was chosen over MNL since HB largely overcomes the independence of irrelevant alternatives issue of MNL22 and provides preference coefficients for each individual respondent. Huber and Train23 found that PWU estimates produced by HB and mixed logit were not significantly different. HB uses the Metropolis Hastings Algorithm, a type of Markov chain Monte Carlo iterative procedure that analyses individual choices at the lower model level using MNL and then analyses the aggregated data at the upper level using multivariate normal methods. The initial burn-in phase was run with 20 000 iterations with 20 000 additional iterations used for estimating the PWUs.

Internal reliability for the DCE was examined by analysing the consistency of the fixed choice tasks that were not included in the main analysis. Statistical significance testing used a 5% level of risk. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and independent sample t-tests conducted in R were used to explore whether significant differences existed in preference coefficients among subgroups formed by the randomised health scenarios and other covariates. The size of the differences between is described using Cohen’s guide to effect24 sizes as represented by eta-squared (or partial eta-squared, but equal here).

Simulations were conducted in Sawtooth Software SMRT using the randomised first choice simulation method. That method was chosen because it attempts to mimic the noise inherent in human decisions by automatically adding appropriate error to the levels of the attributes included in the simulation scenarios, plus an overall error term. We chose the simulation profiles to contain the three most important attributes to ensure a good split in shares-of-preferences and to provide a range of shares across the six scenarios.

Patient and public involvement

This study developed a survey instrument to elicit patient preferences based on previous literature of similar patient surveys, however patients were not involved in creating the version used in this study. Patients were the participants in this study.

Results

The email request to complete the survey was sent to 1285 patients in the two clinics and 378 (29.4%) completed the survey. Recruitment in the waiting room of one of the clinics took place approximately one half-day per week from February to July 2012, resulting in 53 additional completed surveys, for a total of 430 fully complete and usable responses. Most respondents were 40–59 years of age (39%) or 60 and older (32%). The majority of respondents were female (69%). Nearly half (45%) reported having been to the clinic three or more times in the 6 months prior to the survey (table 2). The average age of patients is 48.2 years and 52.5% are female in clinic A, and average age is 45.4 years and 56.3% are female at clinic B.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the respondents who were recruited from a clinic waiting room (n=53) or by email invitation from the clinic (n=377)

| Clinic waiting room (n=53) (A) |

Email invitation (n=377) (B) |

Population of City of Hamilton (2016)29 | |

| Age category (%)* | |||

| 34 and younger | 34.0 | 17.5 | 58.4 |

| 35–49 | 28.3 | 25.2 | 18.9 |

| 50– 60 | 22.6 | 35.0 | 27.1 |

| 65and older | 9.4 | 21.5 | 17.3 |

| Missing | 5.7 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Female (%) | 64.2 | 70.0 | 51.1 |

| Ethnicity—identified as White* (%) | 73.6 | 89.4 | Not available |

| Number of people living in household (%) | 98.3 | ||

| One | 30.2 | 18.0 | 28.2 |

| Two | 26.4 | 39.8 | 32.2 |

| Three | 17.0 | 15.1 | 15.9 |

| Four | 13.2 | 18.8 | 14.6 |

| Five or more | 13.2 | 8.0 | 9.1 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Been a patient of clinic* (%) | |||

| 2 years or longer | 67.9 | 89.7 | Not applicable |

| Less than 2 years | 32.1 | 9.8 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.5 | |

| Perception of health scale rating (mean, SD) | |||

| 0=very poor, 10=excellent | 8.3 (2.2) | 8.1 (2.0) | Not applicable |

*P<0.05 for difference between groups.

The PWUs and 95% CIs from the HB analysis interacting the health states with the individual attribute levels are shown in supplementary table 1. ANOVA and MANOVA tests (p≤0.05) indicated that PWUs for wait time before appointment and familiarity with healthcare provider varied significantly among the health state scenarios and within attributes while not showing significant differences for the other four attributes. The two fixed tasks were not significantly different (χ2=2.86, p>0.20), supporting the internal reliability of the design and data.

bmjopen-2018-023578supp001.pdf (42.1KB, pdf)

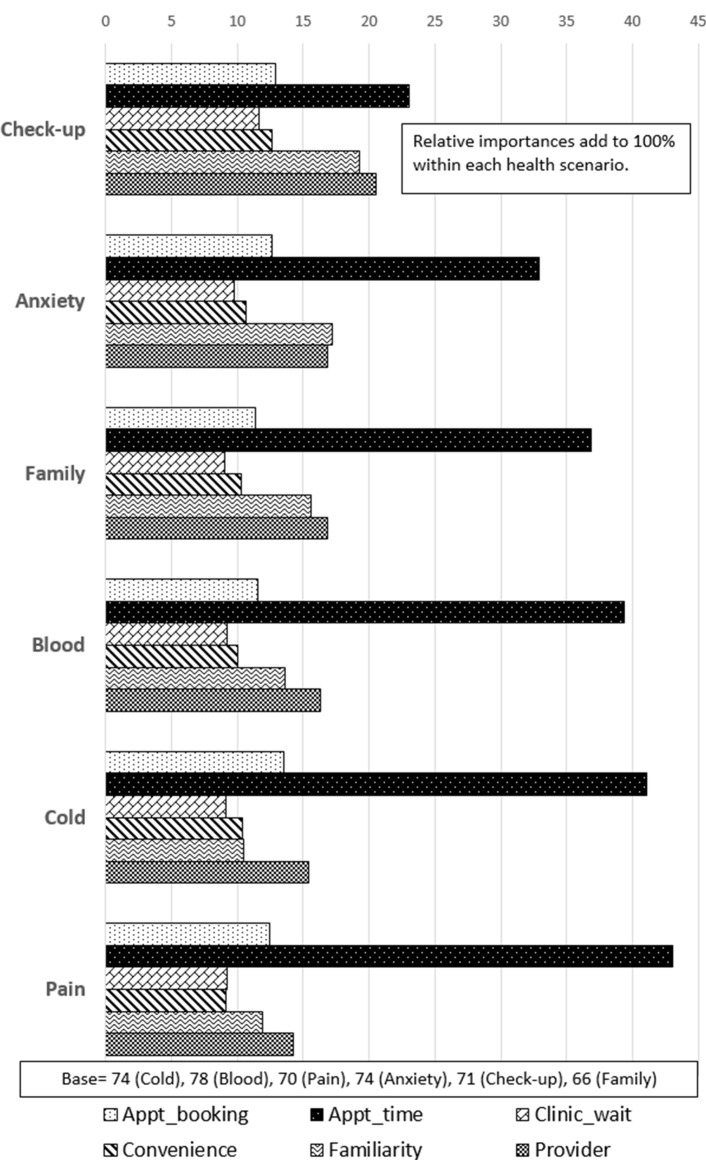

The relative importance of the six attributes for each of the randomised health scenarios is presented in figure 2 and the effect sizes are shown in supplementary table 2. There was significant variation over all six attributes and across the six health scenarios (MANOVA, Wilk’s lambda=0.694, p<0.0001) indicating a range of different responses under the various health conditions. The relative importance of time-to-appointment, waiting room time, familiarity with provider and provider level varied significantly over the six health scenarios. Using Cohen’s guide to effect sizes as represented by eta-squared (or partial eta-squared, but equal here), the effect size of health scenario can be considered large for time-to-appointment, between medium and large for familiarity with provider, between small and medium for waiting room time, appointment convenience and provider level and small for method of booking appointment. The relative importance of time-to-appointment was statistically significantly less (p<0.05) for those responding to the routine check-up scenario than all others. The relative importance of familiarity with provider was statistically significantly greater (p<0.05) for those responding to the routine check-up scenario than for those responding to new cold and new sudden pain and was numerically greater than all others.

Figure 2.

Relative importance of attributes by health scenario.

bmjopen-2018-023578supp002.jpg (533.7KB, jpg)

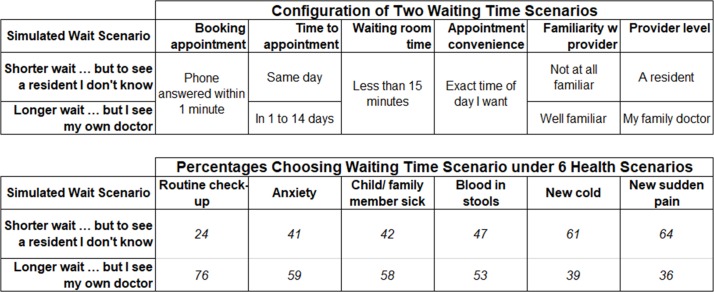

Simulations using the PWUs are presented for each randomised health scenario in the lower frame of figure 3. The numbers in each column show the percentages of patients who would likely choose each of the two simulated access/continuity scenarios when faced with the indicated health scenario. As hypothesised, most patients (76%) would like to have the continuity of seeing their family doctor for a routine check-up and would not mind waiting 1–14 days to see that doctor. On the other hand, 64% of those who responded under the new sudden pain health state wanted an appointment that same day and were willing to see a resident with whom they were not at all familiar. Close to being as insistent for quick service were those who were in the new cold health state, where 61% wanted the same day appointment and only 39% preferred waiting longer to see their own doctor. Those presented with the anxiety, child/family member sick, blood-in-stools health states would rather see their own doctor, but likely would not be quite as demanding for the same day appointment.

Figure 3.

Simulated shares-of-preference for two wait scenarios.

Figure 3 shows one of several simulations conducted to investigate the sensitivity of patients’ preferences for different continuity and access scenarios that might actually be confronted by patients. In both profiles, the appointment was made by a phone call that was answered within 1 min, the waiting room times was less than 15 min and the appointment was at the exact time of day that the patient wanted. In one profile (row 1), the patient’s appointment was scheduled for the same day and the patient would see a resident who was not known to the patient. In the second profile (row 2), the patient would have to wait one to 14 days for the appointment but would see the family doctor with whom the patient was very familiar.

Discussion

In this DCE study of 430 patients, comparing multiple attributes of accessing the primary care clinic, we found that patient choices for appointment bookings in a primary care teaching clinic were primarily influenced by speed of obtaining the appointment (access), followed by the professional position of the healthcare provider (family doctor, resident or nurse/nurse practitioner) and then the patient’s familiarity with the provider (continuity). These results help to demonstrate that an advanced access booking model does in fact target what many patients value most across a number of health states (ie, timely access to their primary care team).

This study was conducted in a jurisdiction where health policy-makers are currently strongly encouraging most, if not all, primary healthcare providers to adopt an advanced access model of appointment bookings.25 Our results lend support to the notion that improved and timely access to primary care seems to be the leading priority for patients as well. In many scenarios tested, patients were willing to trade-off continuity with their usual provider for a shorter wait in the clinic in order to have the offer of a same day appointment. This is the exact reality that teaching clinics and many group practices face, where clinicians are often out of the office either on other rotations in the case of resident physicians, or doing other clinical work in a hospital or long-term care home in the case of staff clinicians. Each patient’s usual provider will not always be available when needed, so other choices must to be offered. In multidisciplinary teaching clinics, those choices are often a provider who the patient has never met, or a resident or nurse who the patient does not know well. On the other hand, there was variability in importance by the health state presented. The relative importance of familiarity with the provider was greater in the context of a routine check-up compared with a new cold and new sudden pain. This finding makes sense since most people are not in a rush to have the routine annual check-up but do like to see their regular health provider for continuity.

These trade-offs between continuity and quick access are made quite routinely when discussing access to primary care. It seems that patients who are accustomed to receiving their care in a teaching clinic setting are willing to make trade-offs between continuity and access attributes for most health states, but prefer to see their usual physician for their annual physical examinations—perhaps reassuring patients that familiar and often more experienced providers are indeed overseeing their care and aware of their ongoing health needs.

The results from this study did seem to differ somewhat from a previous DCEs examining access to primary care. Rubin et al examined patient preferences for booking routine appointments and described trade-offs between rapid appointment access, choice of provider and choice of time.6 They found that for many of their patients sampled, speed of access was not as highly valued as continuity with the same provider or a convenient appointment time. The difference between Rubin’s result and ours, could be due in part to our patient’s having a long-standing relationship with our teaching clinic philosophy and design, where patients agree up front that they will be seen by resident physicians who are only in our clinic for 2 years. For most of the patients in our study, the expectation of continuity with the same provider is often not present from the start, and what matters most is being seen when they need to be seen.

Where is a growing body of literature supporting the importance of increasing both continuity and faster access in practising patient-centred primary care.20 26–28 To suggest that any one or two attributes could be most highly valued by all patients in all health states is a drastic oversimplification of what drives patients to seek care. A major advantage of the study design used in this experiment is the ability to run custom simulations in the DCE, which allowed us to look more closely at real life scenarios and gain deeper understanding of how patients make their choices when accessing primary care services. Our results make clear that while quick access is important for most people, it is not the only priority in certain health states. Primary care systems need to be adaptable enough to offer patients choices to account for variabilities in patient preferences across diverse health states.

This study had some limitations. It was conducted in two clinics that are part of an academic family medicine department and results may not be entirely generalisable to other settings and practice models. We studied a convenience sample of patients who may have been more frequent visitors to the practice and their views may not represent all patients.

Our results and conclusions are based on the attributes and levels included in the DCE we designed. While we followed a robust process to determine which attributes are important and relevant in our context using focus groups of key informants with expert knowledge of the clinical setting as well as previous literature in similar settings, we cannot be sure we captured all important attributes. The appointment booking method is a compound attribute of method and time to book the appointment. We had no desire to separately estimate the booking method (internet or phone) from the booking wait time (‘right now’, ‘less than 1 min’ and ‘1 to 10 min’). Separating the appointment booking method from the time-to-book would have created a situation where prohibitions would have been needed to avoid unrealistic combinations of method and time, thereby reducing the statistical quality of the design. While some may desire to estimate each univariate attribute separately, this compound attribute best supported this research.

As primary care environments experiment with options such as online appointment bookings to further improve convenience for patients, the relative worth placed on this attribute was of particular interest. When looking at the method of appointment booking (online vs phone), there was a preference for phone booking over online booking. This may seem surprising given societies’ general embrace of technology, but this is perhaps a reflection of people’s tendencies to favour things with which they have had experience. Simply put, since patients have never had the option of online booking, they are less likely to appreciate the potential value, although further study will be required to understand this attribute more completely as time evolves.

In conclusion, patients preferred timely access to care over all other attributes for the majority of health scenarios tested in this study. In other words, patients seeking care for sudden pain, new cold-like illness or other episodic ailments are willing to trade-off continuity for the offer of a timely appointment. The exception to this rule is the scenario of a patient booking for a routine check-up where they prefer to see the provider with which they are most familiar. These results support the notion that advanced access booking models which hold most, but not all appointment spots for same day access match up well with patient preferences over a vast array of clinical scenarios.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DO, MH, KD, HQ, GA and DG contributed to conception and design of the study. DO, MH, KD, HQ contributed to data collection. KD analysed the data. DO, MH, KD wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. DO, MH, KD, HQ, GA and DG interpreted results, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a pilot research grant from the Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences/Hamilton Health Sciences research ethics board approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Please contact corresponding author for data access requests.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, et al. A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: Description of the research domain. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1573–88. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00222-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vick S, Scott A. Agency in health care. Examining patients' preferences for attributes of the doctor-patient relationship. J Health Econ 1998;17:587–605. 10.1016/S0167-6296(97)00035-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bower P, Roland M, Campbell J, et al. Setting standards based on patients' views on access and continuity: secondary analysis of data from the general practice assessment survey. BMJ 2003;326:258 10.1136/bmj.326.7383.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fung CH, Elliott MN, Hays RD, et al. Patients' preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. Health Serv Res 2005;40:957–77. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00395.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ 2000;320:1530–3. 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubin G, Bate A, George A, et al. Preferences for access to the GP: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:743–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Longo MF, Cohen DR, Hood K, et al. Involving patients in primary care consultations: assessing preferences using discrete choice experiments. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:35–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gerard K, Salisbury C, Street D, et al. Is fast access to general practice all that should matter? A discrete choice experiment of patients' preferences. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13 Suppl 2:3–10. 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morgan A, Shackley P, Pickin M, et al. Quantifying patient preferences for out-of-hours primary care. J Health Serv Res Policy 2000;5:214–8. 10.1177/135581960000500405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott A. Identifying and analysing dominant preferences in discrete choice experiments: An application in health care. J Econ Psychol 2002;23:383–98. 10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00082-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scott A, Watson MS, Ross S. Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by general practitioners: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:803–14. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00079-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Turner D, Tarrant C, Windridge K, et al. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:132–7. 10.1258/135581907781543021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cameron S, Sadler L, Lawson B. Adoption of open-access scheduling in an academic family practice. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:906–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA 2003;289:1035–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belardi FG, Weir S, Craig FW. A controlled trial of an advanced access appointment system in a residency family medicine center. Fam Med 2004;36:341–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunningham CE, Chen Y, Deal K, et al. The interim service preferences of parents waiting for children’s mental health treatment: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:865–77. 10.1007/s10802-013-9728-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deal K, Marshall D, Dabrowski D, et al. Assessing the value of symptom relief for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment: willingness to pay using a discrete choice experiment. Value Health 2013;16:588–98. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moayyedi P. Helping patients to help themselves: the future for management of ulcerative colitis? Gut 2002;51:309–10. 10.1136/gut.51.3.309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:445–51. 10.1370/afm.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orme B, Charzan K. Becoming an expert in conjoint analysis. Orem, UT: Sawtooth Software, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allenby GM, Rossi PE. There is no aggregation bias: why macro logit models work. J Bus Econ Stat 1991;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huber J, Train K. On the similarity of classical and bayesian estimates of individual mean Partworths. Mark Lett 2001;12:259–69. 10.1023/A:1011120928698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25. McMurchy D. Advancing Practice Improvement in Primary Care: Summary of Proceedings Toronto. 2014. http://ocfp.on.ca/docs/default-source/2015-documents/advancing-practice-improvement-in-primary-care_summary-of-proceedings.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (Accessed 17 Jan 2019).

- 26. Starfield B, Horder J. Interpersonal continuity: old and new perspectives. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:527–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheraghi-Sohi S, Hole AR, Mead N, et al. What patients want from primary care consultations: a discrete choice experiment to identify patients' priorities. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:107–15. 10.1370/afm.816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barua B, Esmail N. Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada 2017 Report | Fraser Institute . 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/waiting-your-turn-wait-times-for-health-care-in-canada-2017 (2018 Mar 13).

- 29. Statistics Canada. Hamilton, C[Census subdivision], Ontario and Hamilton, CDR [Census division], Ontario (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Resleased Novemb. 29, 2017: Statistics Canada Catalogue, 2017. no. 98-316-X2016001 https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (2019 Jan 17). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023578supp001.pdf (42.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023578supp002.jpg (533.7KB, jpg)