Abstract

Objectives

Reducing costs related to functional disabilities and long-term care (LTC) is necessary in ageing societies. We evaluated the differences in the cumulative cost of public LTC insurance (LTCI) services by social participation.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Our baseline survey was conducted in March 2006 among people aged 65 or older who were not eligible for public LTCI benefits and were selected using a complete enumeration in Tokoname City, Japan. We followed up with their LTC services costs over a period of 11 years. Social participation was assessed by the frequency of participation in clubs for hobbies, sports or volunteering. We adopted a classical linear regression analysis and an inverse probability weighting (IPW), with multiple imputation of missing values.

Participants

Functionally independent 5377 older adults.

Primary outcome measures

The cumulative cost of public LTCI services for 11 years.

Results

Even when adjusting for the confounding variables, social participation at the baseline was negatively associated with the cumulative cost of LTCI services. The IPW model showed that in respondents who participated in hobby activities once a week or more, the cumulative cost of LTCI services for 11 years was lower, approximately US$3500 per person, in comparison to non-participants. Similarly, that in respondents who participated in sports group or clubs was lower, approximately US$6000 than non-participants.

Conclusions

Older adults’ participation in community organisations may help reduce future LTC costs. Promoting participation opportunities in the community could ensure the financial stability of LTCI services.

Keywords: long-term care, cumulative cost, social participation, older adults, cost containment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first to demonstrate that social participations among older adults might help lower subsequent long-term care insurance (LTCI) costs.

Our findings are based on an 11-year prospective observational study using public LTCI receipt data in Japan.

Selection bias might have occurred because of the 53% response rate to the baseline survey.

The measurements of social participation rely on self-reported questionnaire.

Introduction

Across the globe, costs related to functional disabilities and long-term care (LTC) are rapidly increasing in societies with ageing populations. Expenses are greater among those with more severe impairments.1 In Japan, in one of the countries experiencing the highest rate of ageing, the proportion of older people is currently 27.3% and is predicted to reach around 40% by 2065.2 Under these circumstances, the costs for LTC insurance (LTCI) are expected to rise from US$100 billion in 2016 to US$210 billion by 2025.

Lowering these costs requires building a sustainable and healthy ageing society which means developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age. The Japanese government implemented a public nursing care insurance law that includes an LTC prevention policy.3 For this policy, a population approach as primary prevention was proposed rather than a high-risk one which was grounded in risk screening based on intervention targeting. Promoting social participation is considered an effective intervention regarding the population approach, which focuses on the entire group of older adults in a community.

Although social participation is an ambiguous concept, Bukov distinguished three types of participation: collective, productive and political.4 In this paper, we focused on involvement in collective activities in formal and informal societal groups at local community. Social participation helps maintain social networks, support and roles, raises self-esteem and self-efficacy and facilitates access to various kinds of information. Several international systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported on the physical, psychological and social benefits of social participation among older people.5–10 For instance, meta-analysis across 148 articles mentioned active engagement in social activities could reduce risk for mortality. In particular, previous observational studies in Japan also found that collective social participation activities such as volunteering, sports clubs and hobbies among older adults lowered the risk of developing depressive symptoms,11–13 the incidence of functional disabilities,14–16 cognitive decline or dementia,17 18 falls19 and immature death.20–23

We hypothesise that if social participation extends healthy life expectancy and reduces the time spent in intensive nursing care, then the cumulative cost of LTCI services might be lower among the participants; however, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that social participation lessens it. In addition, Japanese LTCI services are provided mainly when people aged 65 and over come to require care or support, based on investigation for certification and doctor’s written opinion. The cost of LTCI services is one of the most important issues for the public sector as an insurer. The evidence for contributing to cost-saving has been useful for recent intervention financing schemes that provide economic incentives to service providers, for instance, social impact bonds. In this paper, using data from a follow-up study that took place over a period of 11 years and tracked older Japanese adults, we assessed the differences of the duration period of requiring care level and of the cumulative cost of LTCI services by frequency of social participation in baseline survey.

Methods

Study design

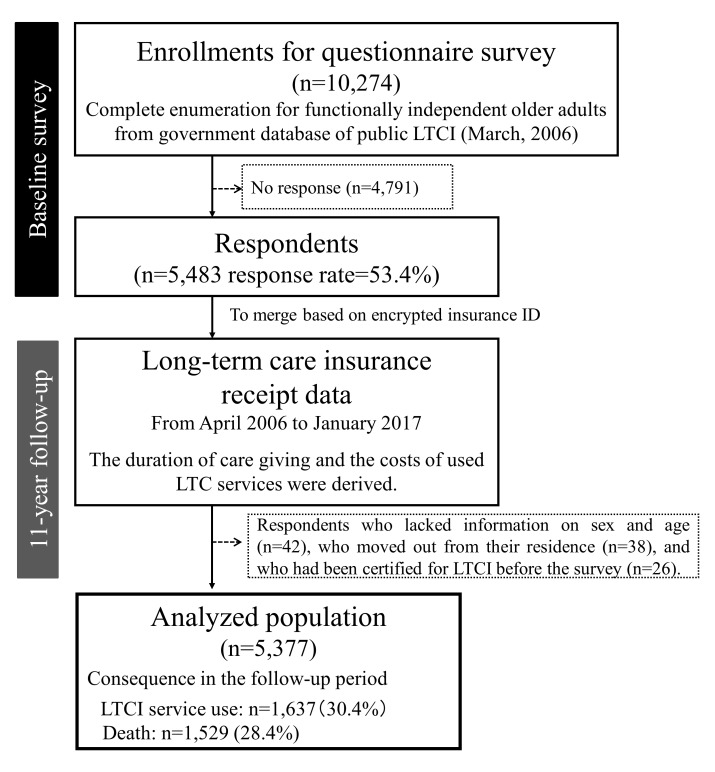

The Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study conducted a self-administered questionnaire in March 2006 as a baseline; 5483 respondents who were 65 years or older, physically and cognitively independent and not eligible for public LTCI benefits were selected using a complete enumeration; they live in the city of Tokoname in Aichi Prefecture (response rate=53.4%: 5483/10 274). In addition, our subjects were more healthy or active older adults at baseline, because Japanese LTCI certifies the people included mild care needs, not only severe care level. Afterwards, we obtained receipt data on LTCI benefits over a period of 11 years after the baseline survey from government database of public LTCI. After eliminating respondents who lacked information on sex and age (n=42), who had moved out of their residence (n=38) and who had been certified for LTCI before the baseline survey (n=26), 5377 respondents were linked to the LTCI receipt data set (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of respondent selection. LTCI, long-term care insurance.

Measurements

Outcome variables: the costs of LTCI services

Primary outcome variable is the cumulative cost of LTCI services at follow-up period. We obtained the LTC costs of insured services across 44 points every 3 months (April, July, October, January) over a period of 11 years. We summed them up after tripling these monthly costs in order to calculate an approximate value of the overall cost for the follow-up period. We used the currency exchange rate of JP¥100 to US$1. As closely related variable, we calculated the number of months which was eligible for LTCI benefit across the whole population, from care level 5 which signifies the highest level of requirement for LTC to any care or support level.

In addition, Japanese LTCI operates based on social insurance principles. Only services are provided, not cash allowances, and recipients can choose their services and providers.24 The receipt data includes information about using insured services such as home visits, day, short stay, residential or in-facility services. The data do not include costs, which are not covered by insurance (such as food, housing and diaper expenses). In general, 10% of these costs are copayments (the municipality, which acts as an insurer, pays 90%), although there is a upper limit to the amount of monthly insurance benefits, which differs depending on the needed level of care. People with certifications for LTC and who need (levels 1 to 5) or require support (levels 1 or 2) can use LTCI services. Those higher levels of care can use more LTCI services through insurance coverage. The cumulative cost of such care in the following cases is zero: deceased individuals who did not have functional disabilities, respondents who did not have proper certification and non-service users.

Explanatory variables: social participation

As mentioned above, social participation is an ambiguous concept. The indicator of social participation was taken from the Japanese General Social Survey,25 and categorised organisations into following eight types as collective social participation activities: hobby activities group, sports group or club, volunteer group, neighbourhood association, senior citizen club/firefighting team, religious group, political organisation or group, industrial or trade association and citizen or consumer group. We focused on the three groups/organisations previously identified as being associated with lower risks for functional disabilities: hobby activities group,17 23 sports group or club15 23 and volunteer group.26 27 According to principal components analysis, these community activities were categorised to horizontal organisations.28 29 Respondents were asked how often they took part in these activities. We categorised them to the four frequencies, respectively: never, a few times a year, once or twice a month and once a week or more.

Covariates

Demographic variables included sex, age, educational attainment, equivalent income (US$), marital status and living situation at the baseline survey. It is well known that these are basic variables as social determinants of health. Age was a continuous variable (73.4±6.2). Years of education was categorised as <6, 6–9, 10–12 and 13+. We equalised household income by the square root of the numbers and classified it as <20.0, 20.0–39.9 and 40.0+ thousand USD. Marital status consisted of married, widowed, divorced and never married. Living situation was categorised as living alone, with one’s spouse only, with a child or with others such as grandchildren, siblings and relatives.

In order to account for the health status at the baseline, the presence of disease or impairment and self-rated health were considered. The presence of disease or impairment was based on self-reported medical condition (no illness, having illness but need no treatment, having illness but discontinued treatment and receiving some treatment). We dichotomised it, that is, no illness or not. We assessed self-rated health using four categories: excellent, good, fair and poor.

Statistical analysis

After calculating the descriptive statistics, we conducted four regression analyses. First, we adopted a classical linear regression (ordinary linear squares [OLS]) model, controlling covariates at baseline survey. We handled the missing value in each control variable as a dummy variable. Second, as one of robustness check, we predicted the marginal effects, adopting a generalised linear model (GLM)30 with Gamma distribution, as well as the log link and robust variance estimator, because our dependent variable (the cumulative cost of LTCI services) is not normally distributed. Next, we performed a multiple imputation technique by chained equations under the missing at random assumption, which means there might be systematic differences between the missing and observed values. We created 20 imputed data sets. Using each data set, we first estimated the OLS model with the robust variance estimator. Finally, in order to estimate the potential outcomes after conditioning on the covariates, we adopted the inverse probability weighting (IPW) model31 32 using the imputed data sets. We calculated the generalised propensity scores using multinomial regression analysis, employing all previously listed covariates. For reference, we only examined the same model among the deceased, who passed away during the follow-up period. The LTCI costs for the deceased indicates the ‘lifetime cost’ of LTCI because they did not use LTCI services at the baseline. We performed analyses using STATA V.15.1 (STATA Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Patient and public involvement

No patient or the public was involved in the development of research question and design of this study. The results of this research will be disseminated to stakeholders such as local and central health government after being published in a scientific journal.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the respondents; the mean age at the baseline was 73.4; 52.0% of the respondents were men. Out of this amount, 30.4% had used LTCI services at least once, and 28.4% passed away during the follow-up period. The average of the cumulative cost of LTCI services during the follow-up period was US$13.7 thousand. The distribution of that was skewed right. There were significant differences in the average duration for the level of care required for social participation across the whole population during the follow-up period (table 2). Non-participants in groups for hobbies, sports and volunteering had a longer duration of certification for LTC at all care levels. For example, among participants who took part in the group for hobbies, the average duration for non-participants was 14.1 (SD=25.8) months, whereas that of those who participated ‘once a week or more’ was 10.6 (SD=21.6) months.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

| Total | Cumulative cost of LTCI services in11 years (US$1000)* | ||

| % | Mean±SD | P value | |

| Sex† | |||

| Male | 52.0 | 7.7±24.8 | |

| Female | 48.0 | 18.7±44.8 | <0.001 |

| Age† | |||

| (Mean±SD) | (73.4±6.2) | ||

| 65–74 | 61.3 | 6.3±25.2 | |

| 75–84 | 33.3 | 23.0±47.2 | |

| 85+ | 5.4 | 39.1±56.4 | <0.001 |

| Disease and/or impairment†* | |||

| None | 27.2 | 10.9±35.5 | |

| Presence * | 64.6 | 14.3±37.8 | |

| Missing | 8.3 | 17.7±39.7 | 0.001 |

| Years of education† | |||

| <6 | 2.7 | 30.7±57.6 | |

| 6–9 | 41.9 | 12.4±34.9 | |

| 10–12 | 24.8 | 13.1±37.2 | |

| 13+ | 32.2 | 11.1±33.3 | |

| Missing | 10.7 | 23.2±48.8 | <0.001 |

| Equivalent income (US$1000)† | |||

| <20.0 | 36.0 | 12.2±36.5 | |

| 20.0–39.9 | 27.3 | 9.5±30.5 | |

| 40.0+ | 6.8 | 12.0±35.5 | |

| Missing | 29.9 | 19.6±43.6 | <0.001 |

| Marital status† | |||

| Married | 69.2 | 9.2±29.7 | |

| Widowed | 21.4 | 24.8±50.2 | |

| Divorced | 1.7 | 11.0±27.9 | |

| Never married | 2.0 | 27.4±60.1 | |

| Missing | 5.7 | 22.7±45.9 | <0.001 |

| Living situation† | |||

| Living alone | 10.7 | 23.8±50.9 | |

| With spouse only | 36.5 | 9.6±30.1 | |

| With child | 22.7 | 12.9±35.9 | |

| With others | 25.6 | 14.6±39.7 | |

| Missing | 4.6 | 21.3±41.6 | <0.001 |

| Self-rated health† | |||

| Excellent | 6.0 | 7.9±30.5 | |

| good | 61.7 | 11.5±34.5 | |

| Fair | 22.5 | 18.2±43.0 | |

| Poor | 5.1 | 21.7±45.6 | |

| Missing | 4.7 | 18.9±39.9 | <0.001 |

| Total | 100.0 | 13.7±37.4 | |

*A breakdown of proportion was as follows: one=32.1%, two=15.2%, three=4.2%, four and over=1.9%, unknown=11.2%. These variables are based on baseline questionnaire survey.

†These variables are based on baseline questionnaire survey.

LTCI, long-term care insurance.

Table 2.

Average duration of care giving at follow-up period by social participation*

| n | ALL* | Care Lv1+ | Care Lv2+ | Care Lv3+ | Care Lv4+ | Care Lv5 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Hobby activities group | |||||||

| Never | 2833 | 14.1 (25.8) | 9.8 (21.4) | 7.1 (17.6) | 4.0 (12.5) | 2.2 (8.5) | 0.8 (4.6) |

| A few times a year | 259 | 9.0 (19.4) | 5.6 (15.7) | 3.5 (9.9) | 1.8 (6.4) | 1.2 (5.3) | 0.6 (4.1) |

| Once or twice a month | 524 | 10.7 (21.8) | 6.1 (16.6) | 4.6 (14.4) | 2.7 (10.2) | 1.6 (7.5) | 0.6 (3.7) |

| Once a week + | 972 | 10.6 (21.8) | 6.2 (16.6) | 4.1 (13.2) | 2.2 (9.3) | 1.0 (6.0) | 0.4 (3.0) |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.019 | p=0.026 | ||

| Sports group or club | |||||||

| Never | 3716 | 13.7 (25.1) | 9.3 (20.7) | 6.6 (17.0) | 3.8 (12.1) | 2.1 (8.4) | 0.8 (4.6) |

| A few times a year | 91 | 7.5 (19.6) | 5.6 (18.4) | 4.8 (16.5) | 2.8 (12.0) | 1.2 (5.5) | 0.8 (5.0) |

| Once or twice a month | 125 | 6.0 (17.3) | 3.3 (13.4) | 2.7 (12.5) | 1.4 (6.9) | 0.5 (2.6) | 0.2 (1.4) |

| Once a week + | 572 | 7.2 (18.1) | 3.8 (12.8) | 2.4 (9.8) | 1.0 (5.4) | 0.5 (3.4) | 0.1 (1.0) |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.005 | ||

| Volunteer group | |||||||

| Never | 3899 | 12.9 (24.4) | 8.6 (20.0) | 6.1 (16.4) | 3.5 (11.6) | 1.9 (7.9) | 0.7 (4.3) |

| A few times a year | 194 | 7.1 (17.3) | 3.9 (12.8) | 2.9 (11.1) | 1.6 (8.3) | 1.1 (7.7) | 0.7 (5.6) |

| Once or twice a month | 193 | 9.9 (21.6) | 6.1 (17.0) | 4.3 (13.3) | 2.0 (8.9) | 1.1 (7.2) | 0.4 (2.7) |

| Once a week + | 122 | 6.4 (17.5) | 3.9 (12.4) | 3.1 (10.9) | 1.6 (6.9) | 0.8 (3.2) | 0.2 (1.5) |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.019 | p=0.165 | ||

*This is including certification for long-term care level from support level one to care level 5.

Unit: month.

The classical regression model showed that in comparison to non-participants, respondents who participated in the group for hobbies once a week produced a cost containment in US$3.6 (95% CI 6.0 to 1.3) thousand, which was lower per person for LTCI cumulative costs over the 11-year period (table 3). Likewise, participating in a sports club was also significantly associated with lower LTCI costs: the category of those who took part ‘once a week or more’ was US$4.9 (95% CI 6.9 to 2.8) thousand less per person. However, in the volunteer group, only less frequent participation was associated with lower costs; for individuals in the category of ‘a few times a year’, this figure was US$4.1 (95% CI 7.1 to 1.0) thousand less per person. When we changed the estimation method to GLM, and when we adopted OLS after multiple imputation, the major results and trends were similar to the above, although some point estimations in GLM were higher in the categories that had a small sample size (please see online supplementary table S1).

Table 3.

Differences of cumulative cost in LTCI services in an 11-year follow-up period by social participation

| n | Mean | OLS ‡§ | IPW with MI ¶†† | Mortality | |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | ||||

| Hobby activities group | |||||

| Never | 2833 | 14.6 | ref. | ref. | 30.8 |

| A few times a year | 259 | 6.6 | −3.2† (−6.7 to 0.2) | −3.5 (−8.1 to 1.2) | 28.0 |

| Once or twice a month | 524 | 10.2 | −2.8† (−5.8 to 0.7) | −2.2 (−5.6 to 1.2) | 21.7 |

| Once a week + | 972 | 9.4 | −3.6** (−6.0 to −1.3) | −3.5* (−6.2 to −0.8) | 19.5 |

| Sports group or club | |||||

| Never | 3716 | 13.9 | ref. | ref. | 29.1 |

| A few times a year | 91 | 9.3 | 2.5 (−4.9 to 9.9) | 1.8 (−5.8 to 9.4) | 18.7 |

| Once or twice a month | 125 | 4.8 | −3.3 (−7.6 to 9.4) | −4.2 (−10.7 to 2.3) | 16.1 |

| Once a week + | 572 | 5.2 | −4.9*** (−6.9 to −2.8) | −6.1*** (−9.3 to −2.8) | 18.6 |

| Volunteer group | |||||

| Never | 3899 | 12.7 | ref. | ref. | 28.4 |

| A few times a year | 194 | 4.8 | −4.1** (−7.1 to −1.0) | −3.9 (−9.1 to 1.3) | 20.7 |

| Once or twice a month | 193 | 10.0 | 1.9 (−2.9 to 6.7) | 1.5 (−3.8 to 6.7) | 12.7 |

| Once a week + | 122 | 5.9 | −0.7 (−4.5 to 3.1) | −1.4 (−7.9 to 5.1) | 11.5 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<.001, †p<0.10. Unit: US$1000.

‡Missing values in control variables were included as a dummy variable.

§The result was controlled by sex, age, disease and/or impairment, years of education, equivalent income, marital status, living situation, self-rated health at baseline.

¶Multiple imputation by chained equations was performed using sex, age, disease and/or impairment, years of education, equivalent income, marital status, living situation, self-rated health at baseline (m=20).

††The generalised propensity scores were calculated using multinominal regression analysis using all previously listed potential confounders: sex, age, disease and/or impairment, years of education, equivalent income, marital status, living situation, self-rated health.

IPW, inverse probability weighting; MI, multiple imputation; OLS, ordinal least squares.

bmjopen-2018-024439supp001.pdf (160.1KB, pdf)

The estimations of IPW showed similar outcomes. In comparison to non-participants, going to a group for hobbies once a week or more resulted in a cost that was reduced by approximately US$3.5 (95% CI 6.2 to 0.8) thousand; for sports clubs, this lowered figure was approximately US$6.1 (95% CI 9.3 to 2.8) thousand. The significant relationship with less frequent participation in the volunteer group disappeared, but the direction of the association and point estimations did not largely change (the C statistics in these models are shown in online supplementary table S2).

In addition, in comparison to non-participants, for deceased individuals during the follow-up period, joining a group for hobbies (once a week+) or sports (once a week+) led to a reduced cost of approximately US$3.9 to US$5.7 thousand and US$9.4 to US$11.4 thousand, respectively (please see online supplementary table S3). These outcomes are preliminary because there were very few analysed subjects (especially the sports and volunteer groups).

Discussions

According to the 11-year prospective cohort study of healthy Japanese older adults, compared with non-participants, respondents who took part in hobby groups or sports activities once a week incurred lower costs for LTCI services (approximately US$3.5 and US$6.1 thousand, respectively, per person), even after demographic variables and health status at baseline were controlled.

These findings are consistent with those of previous research in which several longitudinal studies have shown that older adults who participate in social activities have lower risks of disability,33 functional declines34 35 and mobility declines.36 37 Moreover, it has been suggested that participation in hobby groups, sports clubs and volunteer groups might contribute to reducing the incidence of physical disability risks.15 17 23 26 27 In an intervention study examining the effect of community salons in Japan, it was reported that the incidence of physical disability risks among participants fell by 51% over 5 years38 and that cognitive disability risks declined by around 30% over 7 years.39 Several trajectory analyses have shown that attending leisure activities is related to ‘functional maintenance,’40 while a low frequency of going outside the home was related to being ‘persistently disabled.’41

This study adds evidence to the current literature suggesting that social participation may be effective not only for preventing functional deterioration but also in terms of reducing LTC costs. Our findings also illustrate that the more the respondents took part in each type of community activity, the less time they spent in intensive nursing care. Although the mechanisms behind the relationship between collective social participation and LTCI costs are not fully understood, participating in community activities might contribute to the promotion of physical activities, the maintenance of social role and social networks and the acquisition of important health-related information. Therefore, differences in LTCI costs may have arisen due to extensions to healthy life expectancy or reductions in the periods of functional disability, rather than restrictions on the use of the required services. Lifetime LTCI costs, which were estimated among deceased individuals, showed similar trends. This suggests that postponing the onset of functional disabilities or death did not cause the differences in costs.

On the other hand, for volunteer activities, less frequent (rather than very frequent) participation resulted in lower LTCI costs. In Japan, it has often been mentioned that a portion of those participating in volunteer activities shoulder excessive burdens in terms of supporting those activities, and official Japanese statistics have revealed that half of older adults preferred volunteer activities that do not constrain their time.42 Our results also suggest that being forced to take part in volunteer activities, which is counter to the intended meaning of volunteering, might not necessarily protect the participant’s health, even though participating in and of itself has preventive effects.

It is clear that this study has public health implications. For example, one systematic review mentioned that most local and national public health interventions are aimed at cost saving,43 and our results suggest that promoting participation in community activities might have a non-ignorable cost-containment effect. More specifically, 21.8% and 12.7% of the respondents, or about 2240 and 1300 people, in this municipality may have been participating in hobby or sports groups at least once a week. If those numbers were 10% higher (approximately 220 and 130 people), it may have been possible to reduce the cumulative cost of LTCI services by approximately US$780 to US$800 and US$630 to US$790 thousand, respectively, over an 11-year period. It is important to note that each activities discussed in this paper are not special programmes, and that all of them are already common in Japan. Hence, the additional expenditures to be borne by the public sector would be comparatively minor. It is also suggested that an accumulation of cost impact analyses might be meaningful in terms of public health and community work research. Furthermore, our findings might even be an underestimation because less frequent categories for each type of social participation tend to result in higher mortality rates.

Our study has several limitations and strengths. First, due to restricted data accessibility, we could not analyse medical care costs, which is significant because a previous study mentioned that medical care and LTC expenditures have a weak, but negative, relationship.44 However, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate that social participations among older adults might help lower subsequent LTCI costs. Second, we assessed social participation variables and covariates only at the baseline. More specifically, our study only analysed healthy older adults, excluding those with physically and cognitively disabilities. We also controlled for multiple health dimensions and other covariates by adopting several statistical techniques. However, since the baseline survey was based on a self-reported questionnaire, we cannot deny the possibility of reverse causation. Third, generalisability might be limited by the fact that our study was conducted in one municipality, even though the proportions of older adults and certified LTC levels between the subject area and the national average are roughly the same. Furthermore, selection bias might have occurred because the response rate in our baseline survey was not high (53.4%). However, there are important conclusions that can be drawn from an analysis of merged individual data from this questionnaire regarding social life and public receipt data as they pertain to LTC services. Fourth, there might be measurement bias regarding the actual social participation levels because the data were derived solely from responses to the self-reported questionnaire. Although our indicators have often been used in previous surveys, it is possible that the self-reported activities do not reflect actual participation levels. To assess the frequency and role of these groups, future research should examine interactions among participating members using more objective indicators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank public and private sector staff in this community and other JAGES group members for their helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of this study. Data collection was primarily conducted by MS, YO and KK. Analyses were performed by MS and supported by JA, NK, JS and HK. MS prepared the initial manuscript and JA, NK, JS, HK, AA and KK significantly contributed to revising it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (16K13443, 18H00953, 18H04071), the Research and Development Grants for Longevity Science from AMED (Japan Agency for Medical Research and development, JP18dk0110027, JP18ls0110002, JP18le0110009). The baseline survey data from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES), were conducted by the Center for Well-being and Society, Nihon Fukushi University as one of their research projects. This study was supported in part by MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities, 2009-2013 and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (23243070, 18390200).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Any credits, analyses, interpretations, conclusions, and views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are not open for public due to ethical concerns. Data are from the JAGES study whose authors may be contacted at data management committee: dataadmin@jages.net. The data set has ethical or legal restrictions because it includes human participants.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Boscardin WJ, et al. Functional impairment: An unmeasured marker of medicare costs for postacute care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1996–2002. 10.1111/jgs.14955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Population Projections for Japan: 2016-2065 (With long-range Population Projections: 2066-2115). 2017. http://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/j/zenkoku2017/pp29_ReportALL.pdf

- 3. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Long-Term Care, Health and Welfare Services for the Elderly. 2017. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/index.html

- 4. Bukov A, Maas I, Lampert T. Social participation in very old age: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. Berlin Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:P510–P517. 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, et al. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:445–69. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7 e1000316 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sander R, Cattan M. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Nurs Older People 2005;17:40 10.7748/nop.17.1.40.s11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, et al. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:647 10.1186/1471-2458-11-647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Douglas H, Georgiou A, Westbrook J. Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: an overview of concepts and their associations with health. Aust Health Rev 2017;41:455–62. 10.1071/AH16038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Webber M, Fendt-Newlin M. A review of social participation interventions for people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:369–80. 10.1007/s00127-017-1372-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takagi D, Kondo K, Kawachi I, et al. Social participation and mental health: moderating effects of gender, social role and rurality. BMC Public Health 2013;13:701 10.1186/1471-2458-13-701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsuji T, Sasaki Y, Matsuyama Y, et al. Reducing depressive symptoms after the Great East Japan Earthquake in older survivors through group exercise participation and regular walking: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013706 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shiba K, Kondo N, Kondo K, et al. Retirement and mental health: dose social participation mitigate the association? A fixed-effects longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health 2017;17:526 10.1186/s12889-017-4427-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirai H, Kondo K, Ojima T, et al. Examination of risk factors for onset of certification of long-term care insurance in community-dwelling older people: AGES project 3-year follow-up study. Jpn J Public Health (in Japanese with English abstract). 2009;56:501-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanamori S, Kai Y, Kondo K, et al. Participation in sports organizations and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the AGES Cohort Study. PLoS One 2012;7:e51061 10.1371/journal.pone.0051061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanamori S, Kai Y, Aida J, et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e99638 10.1371/journal.pone.0099638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takeda T, Kondo K, Hirai H, et al. Psychosocial risk factors involved in progressive dementia-associated senility among the elderly residing at home AGES Project–Three year cohort longitudinal study. Jpn J Public Health (in Japanese with English abstract) 2010;57:1054–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saito T, Murata C, Saito M, et al. Influence of social relationship domains and their combinations on incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018;72:7–12. 10.1136/jech-2017-209811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayashi T, Kondo K, Suzuki K, et al. Factors associated with falls in community-dwelling older people with focus on participation in sport organizations: the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study Project. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:1–10. 537614 10.1155/2014/537614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noda H, Iso H, Toyoshima H, et al. Walking and sports participation and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1761–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saito M, Kondo N, Kondo K, et al. Gender differences on the impacts of social exclusion on mortality among older Japanese: AGES cohort study. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:940–5. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishikawa Y, Kondo N, Kondo K, et al. Social participation and mortality: does social position in civic groups matter? BMC Public Health 2016;16:394 10.1186/s12889-016-3082-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ashida T, Kondo N, Kondo K. Social participation and the onset of functional disability by socioeconomic status and activity type: The JAGES cohort study. Prev Med 2016;89:121–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 2011;378:1183–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61176-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osaka university commerce JGSS Research Center. Summary of Surveys. http://jgss.daishodai.ac.jp/english/surveys/sur_top.html.

- 26. Lum TY, Lightfoot E. The effects of volunteering on the physical and mental health of older people. Res Aging 2005;27:31–55. 10.1177/0164027504271349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Musick MA, Wilson J. Volunteering and depression: the role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:259–69. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00025-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aida J, Hanibuchi T, Nakade M, et al. The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:512–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yazawa A, Inoue Y, Fujiwara T, et al. Association between social participation and hypertension among older people in Japan: the JAGES Study. Hypertens Res 2016;39:818–24. 10.1038/hr.2016.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models, second ed: CRC Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoshino T, Okada K. Estimation of causal effect using propensity score methods in clinical medicine, epidemiology, pharmacoepidemiology and public health; a review. J Natl Inst Public Health 2006;55:230–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, et al. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:1149–56. 10.1093/aje/kwj149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social engagement and disability in a community population of older adults: the New Haven EPESE. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:633–42. 10.1093/aje/kwg028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. James BD, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, et al. Relation of late-life social activity with incident disability among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:467–73. 10.1093/gerona/glq231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and limitations in late life. J Health Soc Behav 2011;52:430–43. 10.1177/0022146511411922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Avlund K, Vass M, Hendriksen C. Onset of mobility disability among community-dwelling old men and women. The role of tiredness in daily activities. Age Ageing 2003;32:579–84. 10.1093/ageing/afg101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, et al. Association between late-life social activity and motor decline in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1139–46. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hikichi H, Kondo N, Kondo K, et al. Effect of a community intervention programme promoting social interactions on functional disability prevention for older adults: propensity score matching and instrumental variable analyses, JAGES Taketoyo study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:905–10. 10.1136/jech-2014-205345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hikichi H, Kondo K, Takeda T, et al. Social interaction and cognitive decline: Results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimers Dement 2017;3:23–32. 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu HW, Chiang TL, Chen DR, et al. Trajectories of leisure activity and disability in older adults over 11 years in Taiwan. J Appl Gerontol 2018;37:733464816650800 10.1177/0733464816650800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saito J, Kondo N, Saito M, et al. Exploring 2.5-Year Trajectories of Functional Decline in Older Adults by Applying a Growth Mixture Model and Frequency of Outings as a Predictor: A 2010-2013 JAGES Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol 2019;29:65–72. 10.2188/jea.JE20170230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cabinet Office. Results of survey on attitude toward the senior citizens' economic life (in Japanese). 2011. http://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/ishiki/h23/sougou/zentai/index.html.

- 43. Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, et al. Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71:827–34. 10.1136/jech-2016-208141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suzuki W, Iwamoto Y, Yuda M, et al. The distribution patterns of medical care and long-term care expenditures. Jpn J Health Econ Policy (in Japanese with English abstract) 2012;24:86–107. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024439supp001.pdf (160.1KB, pdf)