Abstract

Objectives

To identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative studies on the experience of living with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related fatigue.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis encompassing a systematic literature search in February 2017, for studies published in the past 15 years, in PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, SveMed, PsychINFO and Web of Science. To be included, the studies had to report the experience of living with fatigue among adults with RA. The analysis and synthesis followed Malterud’s systematic text condensation.

Results

Eight qualitative articles were included, based on 212 people with RA (69% women) and aged between 20 and 83 years old. The synthesis resulted in the overall theme ‘A vicious circle of an unpredictable symptom’. In addition, the synthesis derived four subthemes: ‘being alone with fatigue’; ‘time as a challenge’; ‘language as a tool for increased understanding’ and ‘strategies to manage fatigue’. Fatigue affects all areas of everyday life for people with RA. They strive to plan and prioritise, pace, relax and rest. Furthermore, they try to make use of a variety of words and metaphors to explain to other people that they experience that RA-related fatigue is different from normal tiredness. Despite this, people with RA-related fatigue experience feeling alone with their symptom and they develop their own strategies to manage fatigue in their everyday life.

Conclusions

The unpredictability of RA-related fatigue is dominant, pervasive and is experienced as a vicious circle, which can be described in relation to its physical, cognitive, emotional and social impact. It is important for health professionals to acknowledge and address the impact of fatigue on the patients’ everyday lives. Support from health professionals to manage fatigue and develop strategies to increase physical activity and maintain work is important for people with RA-related fatigue.

Keywords: long-term condition, tiredness, outcome, symptom, interview, impact

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The metasynthesis approach led to new overall understandings, compared with the fragmented findings of individual studies.

The literature search was supervised by a research librarian and encompassed six databases.

Only peer-reviewed articles were included in the synthesis.

The inclusion of eight qualitative studies provided a useful basis for the synthesis.

The findings are useful in relation to people with other types of inflammatory arthritis and long-term conditions where fatigue is a significant symptom.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune inflammatory, fluctuating long-term condition, characterised by pain, fatigue, swollen and stiff joints and potential joint destruction, which can lead to disability. Fatigue in people with RA is highly prevalent, reported by 42%–80% of the patients, and perceived as a dominating problem with a greater impact on everyday life, than pain.1–3

During the past 10–15 years, there has been an increasing research focus on RA-related fatigue, and two different theoretical models have been developed to aid conceptual understanding2 4 where fatigue is understood as a complex and multifactorial subjective experience with disease related, personal, cognitive, psychological and contextual dimensions. Several qualitative studies have revealed that people with RA experience fatigue as an overwhelming symptom influencing their everyday lives and that they struggle alone with their fatigue.3 5–7 However, there is a need for an overall comprehensive understanding and acknowledgement of the experience of RA-related fatigue. With a synthesis of current qualitative research, it is possible to consolidate and add weight to the existing findings from individual qualitative studies,8 9 that normally have little impact on evidence-based practice.8 10 Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative studies on the experience of living with fatigue in patients with RA in order to achieve a higher level and richer understanding of the experience of RA-related fatigue.

Methods

This study used a hermeneutical approach seeking to achieve an increased understanding of the phenomena of living with fatigue.11 We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis based on Sandelowski and Barroso’ approach.12 In accordance with Sandelowski and Barosso,12 the qualitative metasynthesis consists of three phases: (1) a systematic literature search; (2) appraisal of included articles and (3) analysis, synthesis and integration of findings.

Systematic literature search

Two of the authors completed a systematic literature search in February 2017 in six databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, SveMed, PsycINFO and Web of Science. The literature search was performed as block searches.13 The other authors and a research librarian supervised the search. Keywords as well as subject headings were used to strengthen the literature search.14 In each database, thesaurus, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and entry words were identified as equivalent keywords for ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ and ‘fatigue’. The equivalent keywords in each block were combined with OR, before the blocks were combined with AND (online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2018-024338supp001.pdf (177.2KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed studies using a qualitative design, reporting experiences of living with fatigue in patients diagnosed with RA and age >18 years as an outcome. Studies published between 1 January 2002 and 23 February 2017 were included. Only full-text articles in Danish, English, Swedish and Norwegian languages were included. As the experience of fatigue is different depending on peoples’ cultural, psychosocial and economic context,15 16 we excluded studies from non-western countries to ensure homogeneity. We considered western countries to encompass Europe, Canada, USA, Australia and New Zealand. We excluded studies reporting fatigue in people with different diagnoses, if findings regarding people with RA were not reported separately and excluded review articles. The retrieved titles were managed in the electronic reference-program Endnote X7 (endnote.com), where duplicates were removed.

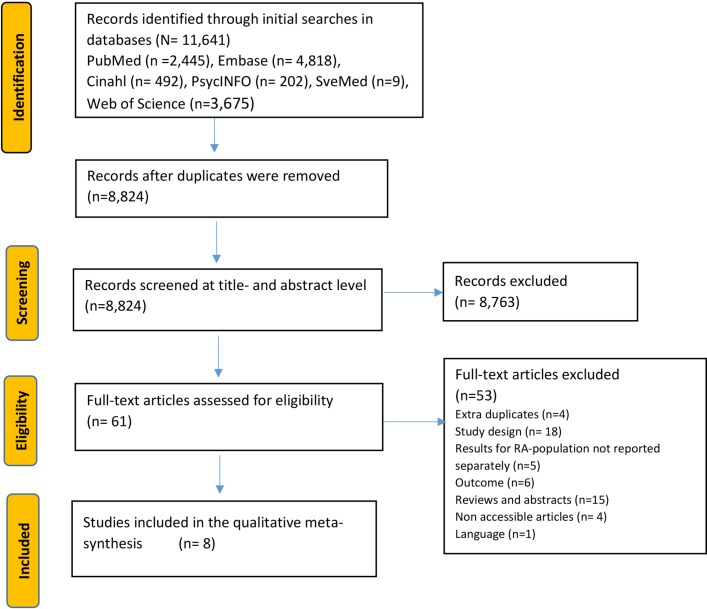

The web-based reference program Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, Covidence.org) was used in the screening process. The next step was full-text screening of 61 articles. Potential conflicts were resolved and agreement obtained through discussions among AH, AL, BAE and JP. The overall literature search and selection process are described in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Description of the literature search.

Appraisal of the included articles

Eight articles were included in accordance with the described inclusion and exclusion criteria (table 1). The combined sample size was 212 people with RA; 69% were women, aged between 20 and 83 years. The checklist from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)17 for assessment of quality in qualitative studies was used. Sampling strategies, data management, discussion, implications and techniques for maximising rigour and credibility were essential issues. The critique of individual studies was further informed by the following selected elements from Sandelowski and Barroso’ reading guide12: judgement about whether plausible findings were appropriately supported by data; if appropriate analysis and interpretation of data were evident; if findings related to the overall aim of the individual study; variation of findings; coherence between and precise reporting of ideas and concepts and finally whether the results offered information or insight in RA-related fatigue.12

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies

| References | Aim | Analysis | Participants | Data collection | Classification of typology |

| Hewlett et al (2005)5 UK | To explore the concept of fatigue as experienced by patients with RA | Thematic analysis grounded in data | 15 patients 3 men/12 women. Age 31–80 years | Semistructured in-depth individual interviews | Conceptual/thematic description |

| Repping-Wuts et al (2008)6 Netherlands | To explore the experience of fatigue in Dutch patients with RA, including the concept, causes and consequences of fatigue, patients’ self-management strategies and bottlenecks in professional care. | Thematic content analysis | 29 patients 12 men/17 women. Age 36–80 years | Questionnaires and individual semistructured interviews | Thematic survey |

| Crowley et al (2009)22 Ireland | To identify barriers to exercise in RA | Grounded theory | 12 patients 12 women Age 43–80 years | Focus groups | Thematic survey |

| Nicklin et al (2010)21 UK | To develop draft PROMs to measure RA fatigue and its impact through collaboration with patients to identify language and experiences, create draft PROM items and test for comprehension. Decisions supported throughout by a patient research partner. | The study consists of three substudies: (1) inductive thematic content analysis, (2) identifying and developing data to use in the third study, and (3) cognitive method of survey methodology | (1) 15 patients, 3 men/12 women. Age 31–80 years (2) 17 patients, 6 men/11 women Age>18 years and (3) 15 patients>18 years | (1) Analysis of transcriptions from a former study of semistructured qualitative interviews, (2) three focus group interviews and (3) cognitive interviews | Conceptual/thematic description |

| Nikolaus et al (2010)7 Netherlands | To gain further insight into the experience of fatigue in RA. | Framework approach combining inductive and deductive elements | 31 patients, 8 men/23 women. Age 32–83 years | Electronic questionnaire and semistructured in-depth individual interviews | Thematic survey |

| Dures et al (2012)23 UK | To explore the patient perspective of a cognitive– behavioural programme for patients with RA and the impact of behavioural changes | Hybrid thematic content analysis | 38 patients, 8 men/30 women. Age 35–77 years | Study nested in a RCT. Focus groups and one individual interview | Thematic survey |

| Feldthusen et al (2012)3 Sweden | To describe how persons with RA of working age experience and handle their fatigue in everyday life | Qualitative content analysis | 25 patients, 6 men/19 women. Age 20–60 years | Individual questionnaires and focus groups | Conceptual/thematic description |

| Thomsen et al (2015)20 Denmark | To examine how patients with RA describe their daily sedentary behaviour | Qualitative content analysis | 15 patients, 5 men/10 women. Age 23–73 years | Semistructured in-depth individual interviews | Conceptual/thematic description |

PROM, patient-reported outcome measures; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

A comparative appraisal12 across the included studies, allowed us to derive metastudy inferences. The eight studies were listed to allow an initial identification of patterns in methods and participants across the included studies (table 1). An audit trail12 (in Danish) documented the procedures and decisions.

Analysis, synthesis and integration of findings

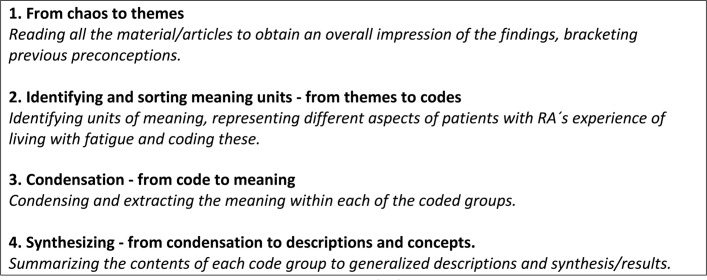

After appraisal of the included studies, we used Malteruds’ systematic text condensation for an interpretive synthesis of the findings18 19 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The stages in Malterud’s text condensation.18 19

Inductive and deductive analysis methods were used alternately. To ensure rigour, a constant movement between fragments and the original text was applied.18 The analysis started with three of the included articles.3 5 6 The rest of the included articles were analysed one by one and, constantly compared with the findings from the other articles.

The initial analysis of the findings resulted in 241 codes. The text bites from the 241 codes were organised into five initial themes. New understandings developed, based on subgroups within each of the initial themes. Eventually, four themes emerged and the findings were described in relation to these four final themes (an example is shown in online supplementary file 2). Text condensation and contextualisation were discussed among the authors to extract the meaning of the emerging themes.

bmjopen-2018-024338supp002.pdf (525.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Due to the nature of this study, no patients were involved in its planning or conduct. The study deals with the patient perspective and a significant and challenging symptom for most patients with RA. The results will be discussed with patient research partners and they will be involved when developing and testing interventions in the future to address fatigue.

Findings

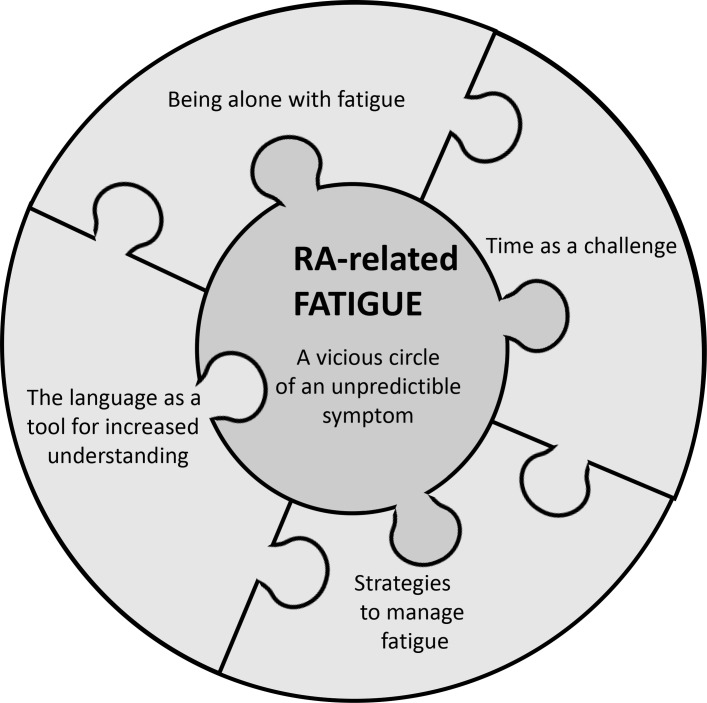

Based on the systematic interpretive analysis, we identified an overall theme ‘A vicious circle of an unpredictable symptom’ and four subthemes, interlinked to each other and to the overall theme: ‘being alone with fatigue’; ‘time as a challenge’; ‘language as a tool for increased understanding’ and ‘strategies to manage fatigue’ (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The interrelated findings of the experience of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related fatigue.

A vicious circle of an unpredictable symptom

Fatigue is one of the most important symptoms for people with RA as it is difficult to control and has considerable consequences for all aspects of their everyday lives.3 5–7 20 They consider their fatigue both to be more intense and different from the fatigue they knew before they were diagnosed and different from the fatigue that people without RA might experience.3 5 21 RA-related fatigue is unpredictable and does not occur regularly within or across days. It varies in severity, duration, frequency and intensity, and varies from short episodes daily, weekly or less often, to fatigue that is more permanent, and can become an overwhelming and total feeling with no specific cause or reason. As such, it is perceived as inexplicable.3 5 6 21 Fatigue can have a cumulative physical, cognitive, emotional and social impact, which forms the basis for a vicious circle, where fatigue wears people down and generates more fatigue.

Physical impact

In the overall theme, physical impact included the experience of fatigue as the main barrier for physical activity and exercise.22 Physical activity becomes extremely exhausting and is associated with irritability and anger.3 5 20 People with RA-related fatigue experience reduced sleep quality, with episodes of being awake at night and feeling unrefreshed after sleep, and a body that feels heavy or as though they are ill.3 5–7 20 21

Cognitive impact

The cognitive impact includes the effect of fatigue on concentration, memory, the ability to learn, solve problems, assimilate information, participate in conversations and engage with others.3 6 21 Fatigue has a negative influence on motivation and enthusiasm.5 6 21 The cognitive problems create a feeling of being limited and always one step behind.6 20 21 People with RA-related fatigue also experience positive effects of their fatigue. This encompasses learning to be more conscious about choices in life, learning to let things pass and recognising the advantages of resting.23

Emotional impact

The emotional impact of fatigue is related to experiences of frustration, hopelessness, fear, reduced motivation, lack of patience and loss of control in relation to other people.3 5 6 21 In addition, fatigue is experienced as exhausting, with a negative impact on people’s ability to take initiatives and to get things done.3 22 A reduced energy to participate in social activities leads to negative feelings such as anger.3 6 7 Younger women with many social roles report being overly sensitive and feeling misunderstood.7 Others report feeling useless.5 7 It is hard to fulfil social expectations which leads to a feeling of being viewed as lazy, boring and self-absorbed.5 They can feel too tired to entertain others or fall asleep, which can induce feelings of guilt and embarrassment.21

Social impact

Social impact of fatigue covers the feeling of being restricted in the ability to fulfil normal social roles in the family, in social life, at work and in recreational activities, and consequently social relations are strained.3 5–7 20–23 People with RA-related fatigue experience the fatigue as a great barrier to being with other people, and they reduce social activities to a minimum.3 5 6 21 Planning and prioritising are important in relation to the experience of fatigue and tasks are divided over a day or over several days in order to be able to manage bad days and save energy for later events and tasks.3 20 The unpredictability makes it hard to plan and the postponement or cancellation of social agreements may be necessary.3 6 20 Work and functional roles are often given higher priority than recreational activities and physical activity and consequently people reduce and limit the time they spend on ‘non-essential’ tasks.3 21 22

Being alone with fatigue

The described emotional and social consequences of fatigue can result in a particular type of loneliness, which people with RA do not share with others. Days with high levels of fatigue lead to isolation at home either because it is difficult to go out or people deliberately choose to be by themselves and stay home.20 They find it hard to reciprocate help and describe this as exhausting, which limits their relationships with other people.3 5 6 21 In particular, people describe how a sense of being dependent on others is detrimental. Fatigue leads to a feeling of imbalance in everyday life, which is dominated by the experience of negative emotions such as hopelessness and loneliness.3 20 People describe not having enough energy to take care of their families, and how this may lead to a feeling of being hard to live with. To manage work, everyday tasks and social activities are a lonely fight and are intensified as people strive not to show fatigue at work or in public.3 It is essential for them not to be perceived as grumpy or whining, but to manage fatigue on their own.3 Their experience of fatigue as a particular symptom is not necessarily articulated in the dialogue with their rheumatologist or nurse specialist.3 6 They believe that support from health professionals is rare and that health professionals tend to focus on physical problems and disease activity rather than fatigue.5 Overall, this leads to the feeling that there is nothing to be done about their fatigue and that the experience of fatigue, its management and acceptance of fatigue is their own problem.3 5 6 20 23

Time as a challenge

Poor sleep and the unpredictable nature of fatigue require breaks and rests during the day. For some people, this means setting time aside, while for others this is perceived as impossible.3 5–7 20 21 Some everyday tasks become slow and troublesome due to joint pain and physical limitations. Tasks take longer than pre-RA and are more strenuous to perform, which can increase fatigue and require more breaks and the need for additional rest.5 6 There is a need to sit down to perform some tasks and a need to be alone, which also takes time and increases the imbalance in everyday life in relation to family life, household and garden related tasks, work, recreational activities and social roles.3 5–7 20 21 As it takes time to adjust plans, the chance to be spontaneous is also reduced.3

The language as a tool for increased understanding

People with RA-related fatigue perceive that other people, who are familiar with ‘normal’ tiredness, are only able to understand fatigue on an intellectual level. Consequently, they do not recognise and understand the far-reaching consequences of this invisible symptom.3 5 21 People experiencing RA-related fatigue are conscious of the words they use with their family and with health professionals to express the meaning of fatigue and increase the understanding of their fatigue.3 5 21 To be ‘tired’ is not considered an appropriate word and they use words such as ‘fatigued’, ‘exhausted’ and ‘lack of energy’.5 21 They use metaphors such as ‘heaviness’ or ‘weight’ or ‘like an infection’ and use different adjectives, that is, ‘frustrating’ and ‘extreme’ to describe their fatigue and facilitate an understanding regarding the nature of their fatigue.6 20 21 People with RA-related fatigue communicate their fatigue differently depending on the context and they expect a reaction from those they talk to.3 They distinguish linguistically among the severity of fatigue, the effect and the management of fatigue.21 When they talk to other people with RA about fatigue, they use words that most people with RA are familiar with.

Strategies to manage fatigue

People with RA-related fatigue report that conscious strategies are needed to break the vicious circle.3 7 They try to pace, relax and rest during the day to save energy for later events and tasks, and be able to manage bad days.5–7 20 21 People with RA-related fatigue constantly prioritise and plan activities according to their capacity to manage fatigue at home and at work.3 5–7 20 21 Other strategies used include breaking down tasks over one or several days or consciously deciding to carry on regardless of the consequences, having a positive attitude or trying to accept the fatigue.3 5 20 Some devote a day per week to manage bad days.3 20 Some can distract themselves from their fatigue by concentrating on something else, engage in social activities, have fun, accept help from others or avoid energy-consuming activities.3 People with RA-related fatigue find it is necessary to take good care of themselves and their body to feel good and try to restore the imbalance in life and ease fatigue.3 People with RA who have participated in group-based cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) to support self-management of fatigue experienced an increased self-efficacy, problem solving, less fear of fatigue and increased acceptance and ability to assert their own needs.23

Discussion

This metasynthesis is the first to summarise and synthesise the qualitative research on the experience of people with RA living with fatigue. We identified that RA-related fatigue is a vicious circle of an unpredictable symptom, which can be described by its physical, cognitive, emotional, social and behavioural impact. These findings are not new, but they are consolidated and strengthened by being consistent across a range of studies. In addition, the four subthemes: ‘being alone with fatigue’; ‘time as a challenge; ‘the language as a tool to an increased understanding’ and ‘strategies to manage fatigue’ based on eight qualitative articles are comprehensive and provide a novel depth of detail into fatigue from a patient perspective. The uncontrollable and unexplained nature of fatigue makes it the most challenging symptom for many people with RA. The findings emphasise that RA-related fatigue is multidimensional and it is pervasive and affects all areas of the people’s everyday lives.

An international cooperation of researchers and patient representatives involved in outcome measures in Rheumatology has acknowledged fatigue as an important symptom of RA, which should be measured in all clinical studies, where possible.24 25 Fatigue can be measured by generic instruments or instruments that reflect the multidimensionality of RA-related fatigue in clinical studies.26 The British Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multidimensional Questionnaire (BRAF-MDQ) is designed to capture the multidimensional nature of RA-related fatigue.27 In addition to the BRAF-MDQ, there are three BRAF numerical rating scales that measure fatigue coping, severity and effect. The BRAFs encompass the physical, cognitive, emotional, social and behavioural aspects of fatigue, the level, the number of days, duration, impact and coping with fatigue. Our study highlighted the importance of wording in relation to fatigue and the BRAFs are based on interviews with people with RA.21 However, the BRAFs do not encompass the challenges with loneliness and time, which we identified as important aspects of living with fatigue. The metaphors provide insight into the negative feelings and the lack of freedom that people experience.20 23 These aspects should be included in the dialogue between health professionals and the patients.

The unpredictability of fatigue creates a changed self-perception and sense of self-worth, which amplifies the physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural impact of the symptom. Professor Charmaz argues that chronic illness can be considered as a fundamental type of suffering which can undermine the person’s ‘self’.28 The unpredictability creates uncertainty and fear which can lead to more restrictions and limitations in life than necessary.28 This is consistent with the findings regarding fatigue in our study. Health professionals can support people with RA-related fatigue in addressing and acknowledging these emotions and issues in the dialogue with people with RA.

We found that people with RA-related fatigue may experience loneliness because they consider that they must opt out of social activities to take care of themselves. They do not feel that other people acknowledge their invisible fatigue and social relations are strained. This is consistent with a study on the experience of living with RA.29 RA puts social roles under pressure in general, both in the family, among friends and in the wider social network.29 Work life is important for people with RA as it affects their identity, social relationships and the sense of normality in everyday life.29 Women with RA give the highest priority to their professional identity compared with a disease and motherhood identity.30 In this metasynthesis, we also found that people with RA prioritise work life and functional roles, and it is their leisure time and family time where RA-related fatigue bears the greatest impact. However, despite often prioritising work, the cognitive and physical impact of fatigue can make it difficult for people with RA-related fatigue to fulfil their role at work.31 Thus, these issues need to be included in the dialogue between patients and health professionals.

Fatigue was considered to be the main barrier to physical activity.22 Physical activity has been found to be associated with physical fatigue in people with RA.32 At the same time, people with RA describe physical activity as one of the strategies they use to manage their fatigue.33 Physical activity can induce a natural sense of fatigue and exhaustion, which are considered positive as opposed to the RA-related fatigue, which is considered unpredictable, unearned and unexplained.33 A recent Cochrane review34 and a meta-analysis on exercise training and fatigue35 identified physical activity as a potentially effective non-pharmacological strategy to help reduce the level of fatigue. Even a reduction in sedentary time seems to reduce the level of fatigue significantly.36 Another efficient strategy is the application of CBT to help people reduce their RA-related fatigue.23 34 37

Our study highlights that patients with RA-related fatigue report that health professionals do not address fatigue sufficiently. Other studies have indicated that health professionals do not possess the necessary competencies to guide the patients to manage their fatigue.38 Thus, further education and training of health professionals to acknowledge and validate fatigue, and in the use of different cognitive–behavioural techniques are needed.23 However, we still need more evidence regarding effective interventions to help reduce RA-related fatigue.

The overall findings from our study fit the models mentioned in the Introduction.2 4 However, the findings regarding loneliness, time, language and strategies to manage fatigue are less recognised and should inform future interventions. A recent study indicates that we may not require disease-specific approaches as the severity of fatigue can largely be explained by transdiagnostic factors.39 Thus, we may develop interventions to help reduce fatigue for people with different chronic diseases targeting individual needs.39 Furthermore, the specific cognitive processes should be mapped and targeted.40

Strengths and weaknesses of the study and in relation to other studies

The huge impact of RA-related fatigue on all aspects of peoples’ lives, the importance of the language, the temporal aspect and how people feel alone with their fatigue presents a comprehensive, detailed picture of the experience of living with RA-related fatigue. Our synthesis strengthens and consolidates the findings from the individual qualitative studies, broadening and deepening our understanding.

The literature search was supervised by a research librarian to enhance the quality, and we consider it to be thorough. To optimise the quality of the included studies, we chose not to include grey literature and abstracts which might not have been peer reviewed.

Additional studies from other areas of the world might have altered the results, but we found it important to limit the study to western countries, as the experience of fatigue might be dependent on, or influenced by, the cultural context. Furthermore, restricting searches to the past 15 years can be considered a limitation as there may be additional studies a few years older. Still, the experience of living with fatigue is affected by the cultural and historical context. Thus, the 15-year limitation seems relevant.

The findings from this study are likely to be relevant and useful for people with other types of inflammatory arthritis and long-term conditions where fatigue is a significant symptom.

Conclusion

The unpredictability of RA-related fatigue is dominant, pervasive and is experienced as a vicious circle, which can be described by its physical, cognitive, emotional and social impact on peoples’ lives. It is important for health professionals to acknowledge the impact of fatigue on the patients’ everyday lives, pay attention to the wording they use to describe their fatigue and to include the experience of living with fatigue in the dialogue with patients. Support from health professionals to manage fatigue and to develop new strategies to increase physical activity and maintain work is important for people with RA-related fatigue.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KL, ED, BAE and JP: idea generation; AH, AGL, BAE and JP: literature search and initial analysis; all authors: final analysis and drafting of the manuscript and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We do not have any additional data to share.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Repping-Wuts H, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: what is known and what is needed. Rheumatology 2009;48:207–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hewlett S, Chalder T, Choy E, et al. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: time for a conceptual model. Rheumatology 2011;50:1004–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feldthusen C, Björk M, Forsblad-d’Elia H, et al. University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care (GPCC). Perception, consequences, communication, and strategies for handling fatigue in persons with rheumatoid arthritis of working age--a focus group study. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:557–66. 10.1007/s10067-012-2133-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matcham F, Ali S, Hotopf M, et al. Psychological correlates of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2015;39:16–29. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hewlett S, Cockshott Z, Byron M, et al. Patients' perceptions of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: overwhelming, uncontrollable, ignored. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:697–702. 10.1002/art.21450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Repping-Wuts H, Uitterhoeve R, van Riel P, et al. Fatigue as experienced by patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:995–1002. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, et al. New insights into the experience of fatigue among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:895–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.118067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bondas T, Hall EO. Challenges in approaching metasynthesis research. Qual Health Res 2007;17:113–21. 10.1177/1049732306295879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paterson BL. Meta-study of qualitative health research: a practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. London: SAGE, 2001:162. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen HP, Draborg E, Kristensen FB. Exploring qualitative research synthesis: the role of patients' perspectives in health policy design and decision making. Patient 2011;4:143–52. 10.2165/11539880-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dahlager LoF H. Hermeneutisk analyse - forståelse og forforståelse (Hermeneutic analysis - understanding and preunderstanding) Vallgårda SoK L, Forskningsmetoder i folkesundhedsvidenskab. København: Munksgaard, 2007:157–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer, 2007:284. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buus N, Tingleff E, Rossen CB, et al. Litteratursøgning i praksis: begreber-strategier‐modeller. (Literature search in practice: concepts-strategies-models). Tidsskrift for Sygeplejersker 2008:10. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eriksen MB, Christensen JB, Frandsen TF. Embase er et centralt værktøj til medicinsk litteratursøgning (Embase is a central tool for medical literature search). Ugeskrift for Læger 2016;17:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Putrik P, Ramiro S, Hifinger M, et al. In wealthier countries, patients perceive worse impact of the disease although they have lower objectively assessed disease activity: results from the cross-sectional COMORA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:715–20. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hifinger M, Putrik P, Ramiro S, et al. In rheumatoid arthritis, country of residence has an important influence on fatigue: results from the multinational COMORA study. Rheumatology 2016;55:735–44. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP-UK). http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (cited Feb 2017).

- 18. Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health 2012;40:795–805. 10.1177/1403494812465030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag (Qualitative research methods for medicine and health) 4. utgave ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomsen T, Beyer N, Aadahl M, et al. Sedentary behaviour in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2015;10:28578 10.3402/qhw.v10.28578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J, et al. Collaboration with patients in the design of patient-reported outcome measures: capturing the experience of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1552–8. 10.1002/acr.20264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crowley L, Kennedy N. Barriers to exercise in rheumatoid arthritis - a focus group study. Physiotherapy 2009;30:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dures E, Kitchen K, Almeida C, et al. "They didn’t tell us, they made us work it out ourselves": patient perspectives of a cognitive-behavioral program for rheumatoid arthritis fatigue. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:494–501. 10.1002/acr.21562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirwan JR, Hewlett S. Patient perspective: reasons and methods for measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1171–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, et al. Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1174–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan JR. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of scales in use. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:429–39. 10.1002/art.22611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J, et al. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study to evaluate the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional questionnaire, visual analog scales, and numerical rating scales. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1559–68. 10.1002/acr.20282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 1983;5:168–95. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kristiansen TM, Primdahl J, Antoft R, et al. Everyday life with rheumatoid arthritis and implications for patient education and clinical practice: a focus group study. Musculoskeletal Care 2012;10:29–38. 10.1002/msc.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feddersen H, Mechlenborg Kristiansen T, Tanggaard Andersen P, et al. Juggling identities of rheumatoid arthritis, motherhood and paid work - a grounded theory study. Disabil Rehabil 2018:1–9. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1433723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Connolly D, Fitzpatrick C, O’Toole L, et al. Impact of fatigue in rheumatic diseases in the work environment: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:13807–22. 10.3390/ijerph121113807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Løppenthin K, Esbensen BA, Østergaard M, et al. Physical activity and the association with fatigue and sleep in Danish patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:1655–64. 10.1007/s00296-015-3274-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loeppenthin K, Esbensen B, Ostergaard M, et al. Physical activity maintenance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:289–99. 10.1177/0269215513501526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:Cd008322 10.1002/14651858.CD008322.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rongen-van Dartel SA, Repping-Wuts H, Flendrie M, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1054–62. 10.1002/acr.22561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomsen T, Aadahl M, Beyer N, et al. The efficacy of motivational counselling and SMS reminders on daily sitting time in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1603–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hewlett S, Ambler N, Almeida C, et al. Self-management of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial of group cognitive-behavioural therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1060–7. 10.1136/ard.2010.144691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Repping-Wuts H, Hewlett S, van Riel P, et al. Fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: British and Dutch nurses' knowledge, attitudes and management. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:901–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Menting J, Tack CJ, Bleijenberg G, et al. Is fatigue a disease-specific or generic symptom in chronic medical conditions? Health Psychol 2018;37:530–43. 10.1037/hea0000598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hughes AM, Gordon R, Chalder T, et al. Maximizing potential impact of experimental research into cognitive processes in health psychology: A systematic approach to material development. Br J Health Psychol 2016;21:764–80. 10.1111/bjhp.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024338supp001.pdf (177.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024338supp002.pdf (525.9KB, pdf)