Abstract

Objective

Given a man’s current prostate- specific antigen (PSA) level, age and family history of prostate cancer, what are the benefits (decreased risk of higher Gleason score [GS] cancer at diagnosis) and harms (increased risk of false-positive biopsy recommendation) of waiting 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5–8 years until the next PSA test?

Design

Prospective cohort.

Setting

All PSA tested men in Stockholm, Sweden, between 2003 and 2015.

Participants

Men aged 50–74 years with at least two PSA tests between 2003 and 2015 (n=174 636).

Main outcome measures

Log-binomial regression to calculate the risk ratio (RR) of GS ≥7 and GS 6 versus benign outcome at prostate biopsy and 12-year cumulative probability of experiencing a false-positive biopsy by testing interval, age, PSA level and first-degree family history.

Results

Men with PSA ≤1 ng/mL had low risk of GS ≥7 prostate cancer irrespective of testing interval; <3% had a PSA >3 at the next testing occasion, and of the 663 men biopsied after the next PSA test only 32 (5%) had GS ≥7 cancer. Men with PSA >1 ng/mL had increased risk of being diagnosed with GS ≥7 prostate cancer when screened with longer than annual intervals (RRs ranged from 1.4 to 3.2 depending on PSA level and testing interval). The results were consistent across age groups and family history status. This benefit needs to be balanced against the increased risk for false-positive biopsy recommendation with shorter testing intervals (twofold for annual vs biennial and threefold for annual vs triennial).

Conclusions

Men aged 50–74 years with PSA ≤1 ng/mL can wait 3–4 years before having a new PSA test. For men with PSA >1 ng/mL, we observed an increased risk of being diagnosed with GS ≥7 prostate cancer with longer than annual testing intervals. This benefit needs to be balanced against the markedly increased risks for false-positive biopsy recommendations with shorter testing intervals recommendations.

Keywords: prostate disease, epidemiology, adult urology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large population-based study with prospectively collected high-quality data from the Stockholm prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and Biopsy Register in Sweden, reflecting contemporary urology and pathology practice.

Limited evidence in other studies on the association of PSA testing intervals and the risk of being diagnosed with Gleason score ≥7 prostate cancer.

With the observational study design follows the potential for confounders.

Introduction

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is widely used to screen for prostate cancer and there is strong evidence that PSA testing reduces prostate cancer mortality.1–3 However, PSA has a high false-positive rate translating into unnecessary prostate biopsies and overdiagnosis of low-risk cancers, resulting in potential overtreatment.4–6 A key component to better balancing the harms and benefit of PSA testing is to find suitable testing intervals.

Prostate cancer screening trials have used 2- or 4-year screening intervals. But since none of these trials randomised patients to different intervals as a primary objective, there is no direct evidence supporting a specific screening interval. The limited available evidence is based on retrospective analyses of data from the screening trials or on modelling.7 8 van Leeuwen et al 7 used data from the Gothenburg and Rotterdam sites of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) to estimate a 43% reduction in the diagnosis of advanced prostate cancer for screening every 2 years (Gothenburg) compared with every 4 years (Rotterdam). The diagnosis of low-risk prostate cancer was, however, 46% higher in Gothenburg than in Rotterdam, indicating increased overdiagnosis. Modelling studies have projected that screening men every 2 years preserves the majority (about 80%) of prostate cancer deaths prevented compared with annual screening while reducing both the number of tests and the chance of a false-positive test by 50% and overdiagnosis by 30%.8

Recommendations on screening interval from various organisations differ. For men who want to participate in prostate cancer screening after shared decision-making, the American Cancer Society recommends biennial screening for men aged 50 years and over with a PSA level of <2.5 ng/mL and annual testing for men with PSA level 2.5 ng/mL or higher,9 the American Urological Association (AUA) recommends biennial testing for men aged 55–69 years,10 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)11 recommends 2- to 4-year intervals for men aged 45–74 years with PSA <1 ng/mL and 1–2 years for men with PSA ≥1 ng/mL. Both the AUA and NCCN also state in their guidelines that the ideal screening interval, in fact, is unknown. After recommending against PSA testing altogether since 2012,12 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in a recent draft statement now recommends offering PSA testing to men aged 55–69 years13 after individualised decision-making. USPSTF gives no explicit recommendation on screening intervals and states that more research on the effect of different screening intervals on benefits and harms of PSA screening is needed.

For breast cancer screening, the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium has a series of well-conducted observational studies evaluated the harms and benefit of different mammography screening intervals.14–16 We here provide similar analyses for prostate cancer screening. Specifically, we aimed to address the following question: given a man’s current PSA level, age and family history of prostate cancer, what are the benefits (decreased risk of higher Gleason score [GS] cancer at diagnosis) and harms (increased risk of false-positive biopsy recommendation) of waiting 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5–8 years until having the next PSA test?

Methods

Data sources

We compiled the Stockholm PSA and Prostate Biopsy Registry through linkages of population based and virtually complete health registries.17 With data from the three clinical chemistry laboratories performing all PSA analyses in Stockholm, Sweden, we identified all men who underwent at least one PSA test in Stockholm since 2003. From the three pathology departments in Stockholm, data were collected on histological examinations of prostate tissue samples from the same geographical area and period. Family relations were obtained from the Swedish Multi-generation Register. Clinical data—including tumour stage, GS and mode of detection (PSA detected or symptomatic detection)—were obtained by linking to the Regional Prostate Cancer Register and the Swedish National Cancer Register. On 23 November 2015, the Stockholm PSA and Biopsy Registry comprised data from close to 448 000 men and 1.8 million PSA tests. The local ethics review board approved the study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, recruitment or conduction of the study.

Definitions, design and study population

We included men aged 50–74 years with and without prostate cancer and with at least two PSA tests between 1 January 2003 and 23 November 2015 (both tests taken prior to diagnosis for men with prostate cancer) (online supplementary appendix figure 1 in the Supplement).

bmjopen-2018-027958supp001.pdf (482.4KB, pdf)

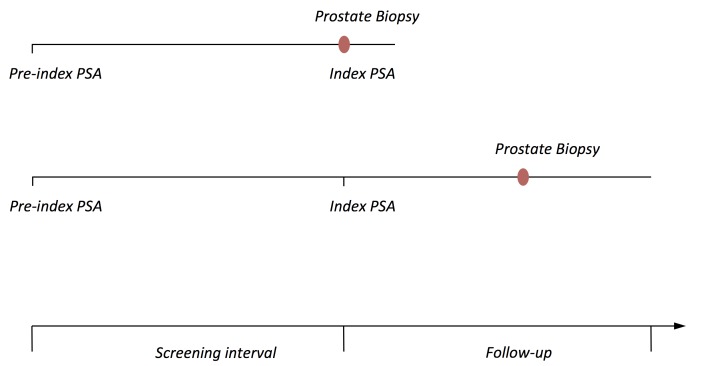

For each man, the intervals between his PSA tests were classified as annual (9–18 months apart), biennial (19–30 months apart), 3 yearly (31–42 months apart), 4 yearly (43–54 months apart) or 5–8 yearly (55–96 months apart) (figure 1). We denote the second PSA test in an interval the index PSA and the first PSA test the pre-index PSA. An elevated PSA is often validated a few weeks later, since the PSA concentration temporarily can be increased by, for example, infections. We therefore considered PSA tests performed within 90 days from each other as part of the same workup procedure and only the chronologically second of these tests entered the analysis. Analyses were restricted to pre-index PSA tests <10 ng/mL and to first biopsies performed within 120 days before referral date of biopsy and within 180 days before the date of cancer diagnosis. Prostate cancers diagnosed symptomatically within 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5–8 years of the index PSA of men tested annually, biennially, 3 yearly, 4 yearly or 5–8 yearly, respectively, were included in the analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Longer testing interval may impact the outcome of a prostate biopsy following the index PSA test due to longer time for a potential tumour to grow from the pre-index PSA to the index PSA, or due to a symptomatically driven biopsy diagnosed during the longer interval between the index PSA and the next PSA test. This study takes both of these aspects of longer testing intervals into consideration by analysing1 prostate cancers diagnosed at a prostate biopsy following a testing PSA; and2 prostate cancers diagnosed symptomatically within the follow-up time of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5–8 years of the index PSA of men who were tested annually, biennially, 3 yearly, 4 yearly or 5–8 yearly, respectively. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

For the analysis of the probability of false-positive biopsy recommendations, we included all men with PSA tests between 1 January 2003 and 23 November 2015 without a history of prostate cancer and without a prostate cancer diagnosis within 180 days after the last recorded PSA test.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarise the population by testing interval and to estimate the proportion of biopsied men with a false-positive biopsy recommendation and with Gleason-specific cancer diagnosis stratified by testing interval, age group, pre-index PSA, index PSA and family history.

We used log-binomial regression to calculate the risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CI for outcomes at first biopsy: (1) false-positive biopsy (benign finding), (2) GS 6 or (3) GS ≥7. Independent variables included testing intervals (1, 2, 3, 4 or 5–8 years), age, pre-index PSA levels (categorised as <1, 1–3, 3–5 and 5–10), number of previous PSA tests and family history of prostate cancer. We adjusted for educational level in the regression model.

We then calculated the cumulative probability for cancer-free men aged 50 or 60 years of having a false-positive biopsy recommendation during 12 years of testing, following previously developed method for calculating cumulative probability of false-positive screening test.15 16 Briefly, we estimated the probability of a false-positive biopsy recommendation at a man’s first PSA test using logistic regression including age, PSA level and family history as covariates in the model. Then, we fit a logistic regression model for false-positive results at each subsequent PSA test conditional on the number of previous PSA tests, testing interval, PSA, age and family history. We combined estimates of the false-positive risk at each subsequent testing round according to age, PSA level and family history to obtain cumulative false-positive probabilities after 12 years of repeated PSA testing. We report fitted values from this model by PSA level at age 50 and 60, testing interval and family history.

To address the effect of potential GS inflation, we performed sensitivity analyses where the time period was restricted to 1 January 2008 to November 2015.

All analyses were performed using R V.3.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All p values and CIs are two-sided 95%.

Results

A total of 174 636 men matched our entry criteria (table 1; online supplementary appendix figure 1). Most men were screened annually (44%) or biennially (23%) (table 1). Older men were screened more frequently than younger men; 56% of men aged 70–74 years were PSA tested annually, whereas 36% of men aged 50–54 years were tested annually. Men with higher pre-index PSA level also had shorter testing intervals in general. Nonetheless, 40% of the men with pre-index PSA <1 were tested annually. There was no difference in testing frequency between men with or without first-degree relatives with prostate cancer.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics by PSA testing intervals for men with and without cancer 2003–2015

| Characteristics | Screening interval | |||||

| 1 year (n=77 472) |

2 years (n=41 035) |

3 years (n=22 269) |

4 years (n=13 016) |

5–8 years (n=20 844) |

All intervals (n=174 636) |

|

| Screening interval, median months | 12.4 | 23.7 | 35.5 | 47.8 | 69.8 | 20.6 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 50–54 | 9009 (36) | 6375 (26) | 3654 (15) | 2121 (9) | 3563 (14) | 24 722 |

| 55–59 | 12 500 (38) | 8187 (25) | 4714 (14) | 2830 (9) | 4675 (14) | 32 906 |

| 60–64 | 16 414 (42) | 9337 (24) | 5213 (13) | 3026 (8) | 4732 (12) | 38 722 |

| 65–69 | 18 078 (46) | 8741 (22) | 4859 (12) | 2999 (8) | 4972 (13) | 39 649 |

| 70–74 | 21 471 (56) | 8395 (22) | 3829 (10) | 2040 (5) | 2902 (8) | 38 637 |

| Pre-index level | ||||||

| 0–1 | 31 159 (40) | 18 916 (24) | 11 027 (14) | 6473 (8) | 11 259 (14) | 78 834 |

| 1–3 | 30 270 (45) | 16 309 (24) | 8564 (13) | 5044 (7) | 7542 (11) | 67 729 |

| 3–5 | 9905 (55) | 3907 (22) | 1822 (10) | 1026 (6) | 1371 (8) | 18 031 |

| 5–10 | 6138 (61) | 1903 (19) | 856 (9) | 473 (5) | 672 (7) | 10 042 |

| Index PSA level | ||||||

| 0–1 | 30 597 (42) | 17 691 (24) | 10 020 (14) | 5703 (8) | 9148 (13) | 73 159 |

| 1–3 | 29 863 (44) | 16 387 (24) | 8830 (13) | 5158 (8) | 8257 (12) | 68 495 |

| 3–5 | 9430 (51) | 4059 (22) | 2001 (11) | 1278 (7) | 1890 (10) | 18 658 |

| 5–10 | 6026 (54) | 2274 (20) | 1122 (10) | 679 (6) | 1127 (10) | 11 228 |

| 10+ | 1556 (50) | 624 (20) | 296 (10) | 198 (6) | 422 (14) | 3096 |

| First-degree family history of prostate cancer | ||||||

| No | 66 743 (44) | 35 878 (24) | 19 514 (13)13 | 11 466 (8) | 18 401 (12) | 152 002 |

| Yes | 10 729 (47) | 5157 (23) | 2755 (12) | 1550 (7) | 2443 (11) | 22 634 |

| Education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 14 855 (45) | 7850 (24) | 4269 (13) | 2379 (7) | 3796 (11) | 33 149 |

| High school | 31 798 (44) | 17 067 (24) | 9267 (13) | 5298 (7) | 8607 (12) | 72 037 |

| University | 30 139 (44) | 15 800 (23) | 8576 (13) | 5241 (8) | 8330 (12) | 68 086 |

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages by row.

PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Of the study population, 11 462 were biopsied; 7798 (68%) had a negative biopsy, 2036 (18%) had cancer with GS 6 and 1628 (14%) cancer with GS ≥7 (table 2). Only 385 (10%) of the cancers were symptomatically detected. Overall, 12% of men biopsied after annual testing interval were diagnosed with GS ≥7, and 19% after a 4-yearly testing interval (unadjusted for pre-index PSA, age and family history). The proportion of GS ≥7 cancers increased with age. For example, 9% of biopsied men aged 50–54 years were diagnosed with GS ≥7 cancer compared with 21% among men aged 70–74 years. The proportion of GS ≥7 cancers was higher among men with higher pre-index PSA level and, more markedly, index PSA. First-degree family history did not increase the proportion of biopsied men with GS ≥7 compared with GS 6 cancer; however, it did increase the proportion of biopsied men with any cancer (GS ≥6) compared with benign biopsy findings from 29% to 41%.

Table 2.

Men with biopsy: distribution of biopsy outcomes by pre-index PSA level, index PSA level, testing intervals, age and family history of PC

| Characteristics | N (n=11 462) |

Gleason ≤6 (n=2036) |

Gleason 3+4 (n=992) |

Gleason 4+3 (n=358) |

Gleason 8+ (n=278) |

≥T3* (n=105) |

Gleason 7+† (n=1628) |

Benign (n=7798) |

| Pre-index PSA level (ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 663 | 52 (8) | 19 (3) | 8 (1) | 5 (1) | 1 (0) | 32 (5) | 579 (87) |

| 1–3 | 5207 | 898 (17) | 404 (8) | 125 (2) | 122 (2) | 33 (1) | 651 (13) | 3658 (70) |

| 3–5 | 3944 | 760 (19) | 397 (10) | 149 (4) | 94 (2) | 36 (1) | 640 (16) | 2544 (65) |

| 5–10 | 1648 | 326 (20) | 172 (10) | 76 (5) | 57 (3) | 35 (2) | 305 (19) | 1017 (62) |

| Index PSA level (ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 184 | 16 (9) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | NA (NA) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 162 (88) |

| 1–3 | 1952 | 348 (18) | 124 (6) | 35 (2) | 19 (1) | 4 (0) | 178 (9) | 1426 (73) |

| 3–5 | 4691 | 899 (19) | 393 (8) | 116 (2) | 71 (2) | 22 (0) | 580 (12) | 3212 (68) |

| 5–10 | 3951 | 702 (18) | 404 (10) | 162 (4) | 127 (3) | 48 (1) | 693 (18) | 2556 (65) |

| 10+ | 684 | 71 (10) | 66 (10) | 44 (6) | 61 (9) | 29 (4) | 171 (25) | 442 (65) |

| Testing intervals (years) | ||||||||

| 1 | 4999 | 910 (18) | 382 (8) | 142 (3) | 82 (2) | 39 (1) | 606 (12) | 3483 (70) |

| 2 | 2533 | 433 (17) | 223 (9) | 77 (3) | 66 (3) | 20 (1) | 366 (14) | 1734 (68) |

| 3 | 1324 | 242 (18) | 106 (8) | 37 (3) | 41 (3) | 14 (1) | 184 (14) | 898 (68) |

| 4 | 930 | 145 (16) | 98 (11) | 39 (4) | 24 (3) | 8 (1) | 161 (17) | 624 (67) |

| 5+ | 1676 | 306 (18) | 183 (11) | 63 (4) | 65 (4) | 24 (1) | 311 (19) | 1059 (63) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 50–55 | 886 | 154 (17) | 61 (7) | 10 (1) | 12 (1) | 1 (0) | 83 (9) | 649 (73) |

| 55–60 | 2032 | 346 (17) | 114 (6) | 36 (2) | 21 (1) | 9 (0) | 171 (8) | 1515 (75) |

| 60–65 | 3332 | 580 (17) | 280 (8) | 105 (3) | 72 (2) | 25 (1) | 457 (14) | 2295 (69) |

| 65–70 | 3928 | 734 (19) | 405 (10) | 133 (3) | 115 (3) | 43 (1) | 653 (17) | 2541 (65) |

| 70–74 | 1284 | 222 (17) | 132 (10) | 74 (6) | 58 (5) | 27 (2) | 264 (21) | 798 (62) |

| Family history of PC | ||||||||

| Yes | 1958 | 476 (24) | 202 (10) | 78 (4) | 62 (3) | 19 (1) | 342 (17) | 1140 (58) |

| No | 9504 | 1560 (16) | 790 (8) | 280 (3) | 216 (2) | 86 (1) | 1286 (14) | 6658 (70) |

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages by row.

*Men with a diagnosed T3 or T4 stage of prostate cancer according to the TNM staging system.

†Gleason 7+ is the combined number of men with Gleason 3+4, Gleason 4+3 and Gleason 8+.

PC, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TNM, tumour, node, metastases.

Biopsy outcome by testing interval

From the log-binomial regression analysis, the effects of different testing intervals on biopsy outcome did not change with age and family history. For simplicity, we therefore show RRs excluding age and family history in table 3; results including these variables are shown in online supplementary appendix table 1. There was no evidence of increased risk of GS ≥7 cancer for men with pre-index PSA ≤1 ng/mL and testing intervals up to 4 years compared with annual testing, but we did observe a significantly increased risk for men with testing intervals of 5–8 years compared with annual testing (table 3 and online supplementary appendix table 1). It should, however, be noted that men with pre-index PSA ≤1 had very low risk to be diagnosed with GS ≥7 cancer at their next PSA test irrespective of testing interval: of the 79 934 men with pre-index PSA ≤1, only 2136 (3%) had a PSA >3 at the next testing occasion, and of the 679 men biopsied after the next PSA test only 32 had GS ≥7 cancer (20 of which were GS 3+4). For men with pre-index PSA level 1–3 ng/mL, longer than annual testing intervals resulted in significantly increased RRs for being diagnosed with GS ≥7 cancer (RRs ranging from 1.3 for biennial testing to 2.5 for testing intervals 5–8 years). For men with a PSA level of 3–5 ng/mL, three out of four RRs were significantly different from 1 ranging from 1.4 for biennial testing to 1.6 for 5-year to 8-year testing intervals. For men with PSA level of 5–10 ng/mL, three out of four RRs were significantly different from 1 ranging from 1.4 for biennial to 2.0 for 5-year to 8-year testing intervals.

Table 3.

Risk ratios for different biopsy outcomes compared with a benign biopsy by pre-index PSA value and PSA testing intervals using 1-year testing interval as baseline

| Outcome | Pre-index PSA value |

Screening interval | |||

| 2 versus 1 year | 3 versus 1 year | 4 versus 1 year | 5–8 versus 1 year | ||

| Gleason score 6 | 0–1 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.6) | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.5) | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.9) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.5) |

| 1–3 | 1.2 (1 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1 to 1.5) | 1 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) | |

| 3–5 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.2 (1 to 1.5) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | |

| 5–10 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1 (0.7 to 1.5) | 1 (0.7 to 1.6) | 1 (0.7 to 1.6) | |

| Gleason score ≥7 | 0–1 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.9) | 0.7 (0.2 to 3.3) | 0.9 (0.2 to 4.1) | 2.8 (1.3 to 6.3) |

| 1–3 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.7) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 2.5 (2 to 3.1) | |

| 3–5 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.7) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 2.5 (2 to 3.1) | |

| 5–10 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) | |

95% CIs in parenthesis.

PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Men with longer testing intervals were not at increased risk of being diagnosed with GS 6 cancer (see table 3), even with testing intervals in the 5-year to 8-year range. RRs were generally in the range 0.7–1.8 for all combinations of pre-index PSA category and testing interval. The only significant out of the 16 comparisons was for 5-year to 8-year intervals for men with pre-index PSA level of 1–3 ng/mL. One significant result in 16 comparisons is on par with what is expected by chance.

Sensitivity analyses where the study period was restricted to 2008–2015 did not materially affect these results (data not shown).

Cumulative probability of false-positive biopsy recommendations

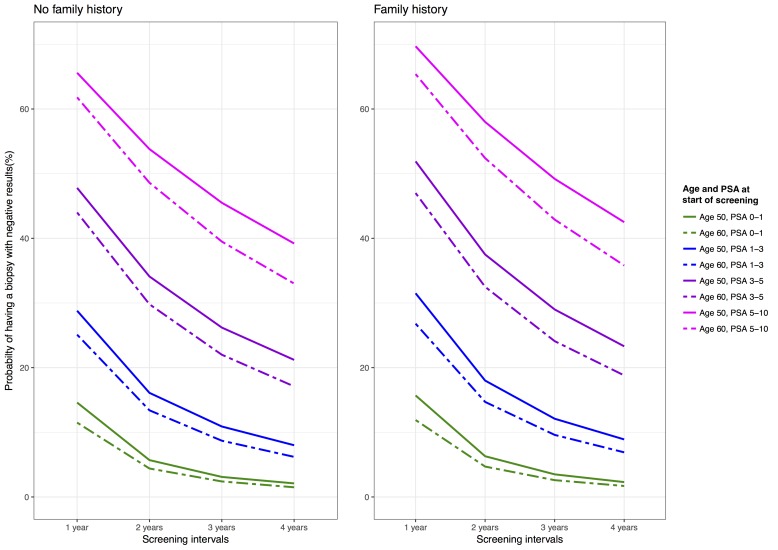

The cumulative probability of at least one false-positive biopsy recommendation for a 50-year-old man with an initial PSA ≤1 ng/mL who undergoes PSA testing for 12 years was estimated to be 15% with annual, 6% with biennial, 3% with 3-yearly testing and 2% with 4-yearly testing (figure 2 and online supplementary appendix table 2). Estimates were slightly higher for men with a positive first-degree family history of prostate cancer compared with men with negative family history. Estimates were somewhat lower for 60-year-old men testing for 12 years. Pre-index PSA level had a great impact on the probability of experiencing a false-positive biopsy: for example, it was estimated to be about 62% for 60-year-old men without family history of prostate cancer and with pre-index PSA level of 5–10 ng/mL testing annually for 12 years, whereas it was about 12% for 60-year-old men with PSA ≤1 ng/mL. The highest cumulative probability for having at least one false-positive biopsy during 12 years of testing was for young men with high PSA levels for benign reasons (70%). This group of men is, however, small: for example, the number of men aged 50–54 years with PSA levels of 5–10 ng/mL and no subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis was 465 (0.2% of the men in the study population).

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of having a biopsy with negative results for different testing intervals after 12 years of testing by age at start of testing, pre-index PSA at start of testing and first-degree family history status. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

In summary, the cumulative probability of receiving at least 1 false-positive biopsy recommendation after 12 years of testing (1) decreased as testing interval increased, (2) increased with pre-index PSA and (3) was only marginally affected by age and first-degree family history of prostate cancer (figure 2 and online supplementary appendix table 2).

Restricting study period to 2008–2015 had only marginal effects on these results (data not shown).

Discussion

Screening intervals play an important role in efficiently using PSA to screen for prostate cancer while reducing overtesting and, consequently, the number of unnecessary biopsies and overdiagnosis. We found that men with pre-index PSA ≤1 ng/mL (45% of men aged 50–74 years) have very low risk to be diagnosed with GS ≥7 cancer at their next PSA test irrespective of testing interval, supporting previous long-term forecasts of risk based on PSA.18 19 Screening this group of men every second, third or forth year instead of annually markedly reduced the risk of false-positive biopsy recommendations over 12 years of testing from almost 15% to 6%, 3% and 2%, respectively. As many as 40% of men with PSA ≤1 in our dataset were tested annually (despite no recommendation for prostate cancer testing in Sweden) and would benefit from less intensive testing.

Men with pre-index PSA >1 ng/mL are more likely to be diagnosed with GS ≥7 disease if they undergo PSA testing with longer than 1-year intervals. This benefit is counterbalanced by a higher risk of cumulative false-positive results, which roughly doubles with annual testing compared with biennial and triples compared with triennial testing. It should also be noted that although the risk of GS ≥7 diagnosis increases with longer testing intervals for men with pre-index PSA >1 ng/mL, the absolute increase in risk for men with pre-index PSA level in the range 1–3 ng/mL is still small (only 651 of 67 729 men with pre-index PSA level 1–3 ng/mL were diagnosed with GS ≥7 at the next PSA test).

Longer testing intervals do not seem to increase the risk of being diagnosed with GS 6 cancer. This result suggests that the risk of being diagnosed with GS 6 prostate cancer is proportional to the risk of being biopsied. Since longer testing intervals decrease the risk of being biopsied, finding a balance between testing intervals and a man’s PSA level is key for reducing overdiagnosis of low GS prostate cancer.

We found that age, family history of prostate cancer and educational level did not affect the association between different testing intervals and risk of being diagnosed with GS ≥7 or GS 6 cancer, or the cumulative 12-year probability of a false-positive biopsy. In other words, the benefit and harm of shorter or longer testing intervals seem to be similar for younger and older men and for men with and without first-degree relatives with prostate cancers. To investigate the potential effect of inflated GSs over time, we performed sensitivity analyses where data were restricted to the study time 2008–2015, after the International Society of Urology Pathology standardisation in 2005. The results for 2008–2015 were very similar to the results for 2003–2015, and we, therefore, chose to present results for the entire study period to maximise statistical power.

Our results are consistent with data from the Gothenburg and Rotterdam sites in the ERSPC as well as modelling studies on the effect of testing intervals on the diagnosis of prostate cancer,7 8 20 where testing intervals of 4 years or longer for men with raised PSA level increased the number of GS ≥7 cancers.

Strengths of our study include the large and high-quality data source, reflecting contemporary urology and pathology practice. Our study also includes a number of limitations. With the observational study design follows the potential for confounders. For example, general health, morbidity and lifestyle may affect the PSA testing frequency. We therefore adjusted for PSA level, educational level and family history in our analysis. We performed a large number of analyses and some of the comparisons may be significant by chance. It is therefore important to consider the magnitude of differences and CI widths. The study participants are primarily of European descent and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution for other ethnicities. Finally, due to limited follow-up, we have not studied prostate cancer mortality as an endpoint. Thus, we do not know if the observed increase in GS ≥7 tumors with longer testing intervals translates into differences in prostate cancer mortality.

When considering recommendations regarding testing intervals, the potential benefit of diagnosing cancers at an earlier stage must be weighed against the increased risk of harms associated with more frequent testing, such as false-positive biopsy recommendations and overdiagnosis of low-risk cancer. Risk prediction models (eg, S3M, 4K, PHI and RC321–24) and pre-biopsy MRI25 have shown to reduce the harms of prostate cancer testing and should together with tailored testing intervals be part of a systematised and individualised pipeline for prostate cancer diagnostics to reduce unintended consequences of testing and lower prostate cancer mortality.

In conclusion, men aged 50–74 years with PSA ≤1 ng/mL can wait 3–4 years before having a new PSA test, which reduces the risk of false-positive biopsy recommendation with a factor of 3–4. For men with PSA >1 ng/mL, we observed an increased risk of being diagnosed with GS ≥7 prostate cancer with longer than annual testing intervals. This benefit needs to be balanced against the markedly increased risks for false-positive biopsy recommendations with shorter testing intervals recommendations. The results were consistent across the entire studied age range and family history status and add to the limited evidence about the potential benefits and harms of screening that policymakers can use to set guidelines about screening intervals and men can use when deciding on whether to undergo screening for prostate cancer or not.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Data access: TP and ME had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: TP and ME. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: TP, ME, AK, TN and HG. Statistical analysis: TP, AK, MC and ME. Drafting of the manuscript: TP and ME. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: TP, ME, AK, TN and HG. Obtained funding: HG, MC and ME. Study supervision: MC and ME.

Funding: Funding was provided by the Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden), the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet), Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), Swedish e-Science Research Center (SeRC) and the Nordic Information for Action eScience Center (NIASC).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: HG has five prostate cancer diagnostic-related patents pending, has patent applications licensed to Thermo Fisher Scientific and might receive royalties from sales related to these patents. ME is named on four of these five patent applications. Karolinska Institutet collaborates with Thermo Fisher Scientific in developing the technology for the Stockholm3 prostate cancer diagnostic prediction model. Other authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the research ethics board at the Regional Ethics Testing Board, Stockholm; EPN DnR 2012/438-31/3.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data are only available for researchers within Karolinska Institutet.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014;384:2027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stattin P, Carlsson S, Holmström B, et al. Prostate cancer mortality in areas with high and low prostate cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju007 10.1093/jnci/dju007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, Mariotto A, et al. Quantifying the role of PSA screening in the US prostate cancer mortality decline. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:175–81. 10.1007/s10552-007-9083-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eggener SE, Badani K, Barocas DA, et al. Gleason 6 prostate cancer: translating biology into population health. J Urol 2015;194:626–34. 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmed HU, Arya M, Freeman A, et al. Do low-grade and low-volume prostate cancers bear the hallmarks of malignancy? Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e509–e517. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70388-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2014;65:1046–55. 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Leeuwen PJ, Roobol MJ, Kranse R, et al. Towards an optimal interval for prostate cancer screening. Eur Urol 2012;61:171–6. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gulati R, Gore JL, Etzioni R. Comparative effectiveness of alternative prostate-specific antigen--based prostate cancer screening strategies: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:145–53. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brooks DD, Wolf A, Smith RA, et al. Prostate cancer screening 2010: updated recommendations from the American Cancer Society. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102:423–9. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30578-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2013;190:419–26. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Network NCC. Prostate Cancer (Version 1.2016). p. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/prostate/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:120–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ. The US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 Draft Recommendation Statement on Screening for Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2017;317:1949 10.1001/jama.2017.4413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Hubbard RA, et al. Outcomes of screening mammography by frequency, breast density, and postmenopausal hormone therapy. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:807–16. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hubbard RA, Kerlikowske K, Flowers CI, et al. Cumulative probability of false-positive recall or biopsy recommendation after 10 years of screening mammography: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:481–92. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hubbard RA, Miglioretti DL, Smith RA. Modelling the cumulative risk of a false-positive screening test. Stat Methods Med Res 2010;19:429–49. 10.1177/0962280209359842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nordström T, Aly M, Clements MS, et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is prevalent and increasing in Stockholm County, Sweden, Despite no recommendations for PSA screening: results from a population-based study, 2003-2011. Eur Urol 2013;63:419–25. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Björk T, et al. Prostate specific antigen concentration at age 60 and death or metastasis from prostate cancer: case-control study. BMJ 2010;341:c4521 10.1136/bmj.c4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ulmert D, Cronin AM, Björk T, et al. Prostate-specific antigen at or before age 50 as a predictor of advanced prostate cancer diagnosed up to 25 years later: a case-control study. BMC Med 2008;6:6 10.1186/1741-7015-6-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saarimäki L, Hugosson J, Tammela TL, et al. Impact of Prostatic-specific Antigen Threshold and Screening Interval in Prostate Cancer Screening Outcomes: Comparing the Swedish and Finnish European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer Centres. Eur Urol Focus 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.07.007 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.euf.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grönberg H, Adolfsson J, Aly M, et al. Prostate cancer screening in men aged 50-69 years (STHLM3): a prospective population-based diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1667–76. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00361-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vickers A, Cronin A, Roobol M, et al. Reducing unnecessary biopsy during prostate cancer screening using a four-kallikrein panel: an independent replication. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2493–8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tosoian JJ, Druskin SC, Andreas D, et al. Prostate Health Index density improves detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. BJU Int 2017;120:793–8. 10.1111/bju.13762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cavadas V, Osório L, Sabell F, et al. Prostate cancer prevention trial and European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer risk calculators: a performance comparison in a contemporary screened cohort. Eur Urol 2010;58:551–8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Valerio M, Donaldson I, Emberton M, et al. Detection of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Ultrasound Fusion Targeted Biopsy: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol 2015;68:8–19. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027958supp001.pdf (482.4KB, pdf)