Abstract

Objective

To assess the magnitude of suicide rates in the first week and first month postdischarge following psychiatric hospitalisation.

Design

Meta-analysis of relevant English-language, peer-reviewed papers published in MEDLINE, PsycINFO or Embase between 01 January 1945 and 31 March 2017 and supplemented by hand searching and personal communication. A generalised linear effects model was fitted to the number of suicides, with a Poisson distribution, log link and log of person years as an offset. A random effects model was used to calculate the overall pooled rates and within subgroups in sensitivity analyses.

Outcome measures

Suicides per 100 000 person years in the first week and the first month after discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation.

Results

Thirty-four included papers comprised 29 studies that reported suicides in the first month postdischarge (3551 suicides during 222 546 patient years) and 24 studies that reported suicides in the first week postdischarge (1928 suicides during 60 880 patient years). The pooled estimate of the suicide rate in the first month postdischarge suicide was 2060 per 100 000 person years (95% CI=1300 to 3280, I2=90). The pooled estimate of the suicide rate in the first week postdischarge suicide was 2950 suicides per 100 000 person years (95% CI=1740 to 5000, I2=88). Eight studies that were included after personal communication had lower pooled rates of suicide than studies included after data extraction and there was evidence of publication bias towards papers reporting a higher rate of postdischarge suicide.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the presence of marked heterogeneity between studies and the likelihood of bias towards publication of studies reporting a higher postdischarge suicide rate, the first week and first month postdischarge following psychiatric hospitalisation are periods of extraordinary suicide risk. Short-term follow-up of discharged patients should be augmented with greater focus on safe transition from hospital to community care.

PROSPERO registration number

PROSPERO registration CRD42016038169

Keywords: risk management, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Published and previously unavailable data were synthesised to estimate rates of suicide in the first week and first month postdischarge following psychiatric hospitalisation.

Pooled rates of suicide were about 3000 and 2000 per 100 000 person years, respectively, in the first week and first month postdischarge.

Published studies reported higher suicide rates than data obtained by personal communication.

High between-study heterogeneity and the likelihood of publication bias towards studies with higher suicide rates may impact the generalisability of our estimated rates.

The period immediately following discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation should be regarded as a distinct phase of care associated with an extraordinary suicide risk.

Introduction

A recent meta-analysis of suicide mortality after discharge from psychiatric facilities estimated a rate of 484 per 100 000 person years among 100 studies reporting on suicides after any period of follow-up and 1132 suicides per 100 000 person years among 18 studies reporting on suicides in the first 3 months.1 These alarming figures suggest that the suicide rate among this vulnerable patient group is up to 100 times the global suicide rate and that being a recently discharged patient confers a higher risk of suicide death than any other risk factor.2 However, the earlier meta-analysis did not report estimates over periods shorter than 3 months1 because the methods used excluded the duplicated patient samples with a smaller number of patient years and no steps were taken to obtain further data by personal communication. As a result, the earlier study included only two studies that reported suicide rates in the first month post hospital discharge.1 Although several primary studies have reported on suicide in the immediate postdischarge period,3–5 expected rates of suicide in the first week and month of transition from the hospital to the community remain uncertain. Knowledge of the extent and trajectory of the suicide risk in the weeks following hospital discharge would inform the timing and duration of interventions aimed at reducing these tragic events.

The primary aim of this study was to calculate a pooled estimate and statistical dispersion (range, median and quartile values) of 1-week and 1-month postdischarge suicide rates. The secondary aim was to examine the possible moderators of the suicide rates over these two periods of follow-up according to the characteristics of the primary research.

Methods

The meta-analysis was registered with PROSPERO6 and conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses7 and Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology8 guidelines.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We included longitudinal studies that reported the number of person years and the number of suicides in the first week (1-week) and first month (or 28 days) postdischarge (1-month) from acute adult psychiatric hospitalisation. We defined acute adult psychiatric hospitalisation broadly so as to include hospitalisations of patients admitted with specific psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatric discharges of older people and after psychiatric hospitalisation in military settings. We excluded studies of postdischarge suicide after release from child and adolescent psychiatric wards, long-stay mental health wards, forensic psychiatric facilities and patients who were admitted to non-psychiatric settings (such as emergency departments or the medical or surgical wards of general hospitals). Studies were excluded if the number of suicides and the number of person years were not reported, could not be calculated or could not be obtained by email from the authors.

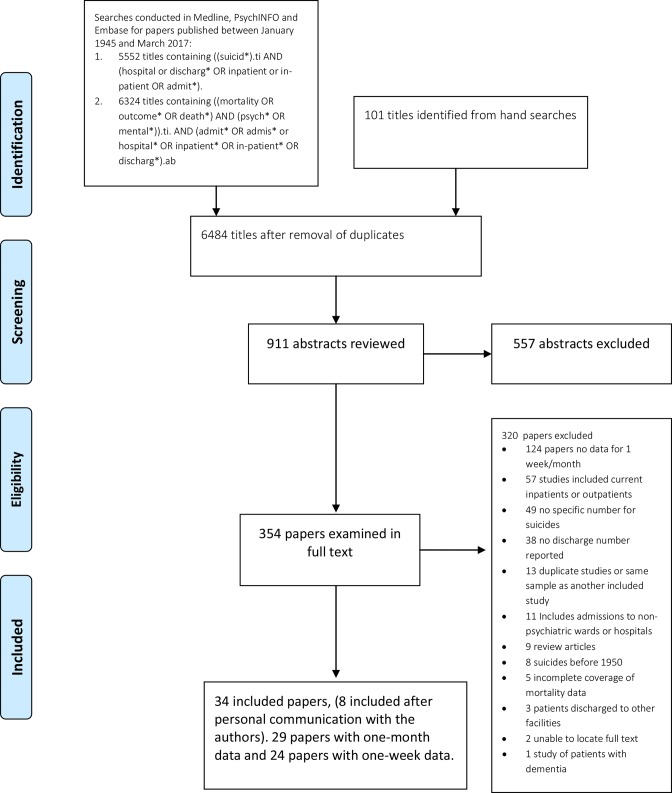

Two authors (DC and ML) independently searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Embase for relevant papers published in English between 01 January 1945 and 31 March 2017 (see figure 1, online supplementary 1). Electronic searches were supplemented by hand searches of the relevant review articles and the full-text papers located in the searches conducted for a related meta-analysis1 were re-examined. Grey literature was not considered. DC and ML independently winnowed titles, abstracts and full-text papers. The authors of studies that met inclusion criteria except for reporting postdischarge suicide rates over periods of longer than a month were contacted by email for data regarding suicides in the 1-week and 1-month periods. Authors of papers that reported postdischarge suicide in 1-month but not reported 1-week and the converse were also contacted. A total of 27 authors were contacted.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

bmjopen-2018-023883supp001.pdf (767.9KB, pdf)

Data extraction

SS and MW independently extracted the data and ML and DC performed a further check of the data. The number of person years was calculated using the number of discharges and the period of follow-up of 28 or 31 days when it was not directly reported in the paper. Where the follow-up was specified to be ‘1-month’, the length of follow-up was assumed to be 365/12=30.4 days. Separate figures were extracted for men and women and for the first and subsequent weeks of follow-up where possible.

A predetermined list of effect size and moderator variables was extracted. The variables collected were (1) number of suicides and number of patient years, (2) period of follow-up (1-month vs 1-week), (3) sex (where specified), (4) diagnostic group (where specified), (5) whether the primary study only included people admitted for suicidal thoughts and behaviours, (6) country in which the study was conducted, (7) whether the data were obtained by personal communication with the authors and (8) study quality items.

We assessed study quality using a 0–4-point scale derived from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies9 and used in a previous meta-analysis of postdischarge suicide rates.1 One point was awarded if the study: (1) identified suicides using coroners’ records or a national mortality database (rather than using hospital records), (2) included all the postdischarge suicides in a defined geographic region (rather than suicides from a particular care setting), (3) included open verdicts in suicide numbers and (4) reported the number of discharges (rather than the number of individuals). Studies with a total quality score of three or four were regarded as being of higher quality.

Data analysis

The effect sizes of interest were the incidence rate (IR), expressed as suicides per 100 000 person years and the incidence rate ratio (IRR) between subgroups. In all analyses, a generalised linear mixed effects model was fitted to a count response (number of suicides), with a Poisson distribution, log link and log of person years as an offset allowing the inclusion of fitted values for zero suicide studies. All models included a random effect (intercept) for study. CIs were based on t-distribution with df equal to the number of studies. All models were fitted with the R package lme4. Standard errors were calculated using the delta method from the R package car. Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted according to the period of follow-up, source of the data (published or obtained by personal communication), country of publication, sex and study quality using a mixed effects model.

Publication bias was examined by (1) comparing extracted data to that obtained by personal communication, (2) examination of funnel plots and (3) Egger’s regression tests based on the fitted values.

Patient and public involvement

The results of this study were discussed with Eastern Suburbs Mental Health Service, Consumer Advisory Group.

Results

Search results and data extraction

Independent searches (DC and ML) both identified 24 of 26 papers reporting on suicides occurring in the first week or first month after discharge. A further eight studies were included after data were provided by personal communication with the authors, such that either 1-week or 1-month data or both periods were available from 34 papers (table 1, online supplementary 21). The earliest study was published in 1983, the median year of publication was 2009 and the most recent was published in 2017. Twenty-nine papers contained data pertaining to the first month postdischarge (online supplementary 3). Twenty-four papers reported on suicides in the first week postdischarge (online supplementary 4).

Table 1.

List of included studies

| Study | Location | Period | Suicide ascertainment | Type of patient | Discharges | Suicides in the first week | Suicides in the first month |

| Castelein et al (2015)31 | Psychiatric hospitals in Groningen, the Netherlands | 2000–2011 | Regional psychiatric case register | Recent onset psychosis | 424 | 1 | – |

| De Leo and Heller (2007)32 | Gold Coast Hospital, Queensland, Australia | 2002–2005 | Not specified | Previous suicide attempters | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| Deisenhammer et al (2016)33 |

Three psychiatric hospitals, Tyrol, Austria | 2004–2011 | Not specified | Unselected adults | 65 652 | 25 | 51 |

| Erlangsen et al (2006)34 | All psychiatric hospitals, Denmark | 1990–2001 | Coronial records | Adults aged>60 years | 72 701 | 77 | – |

| Geddes and Juszczak (1997)5 | All psychiatric hospitals, Scotland, UK | 1968–1993 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 338 013 | – | 367 |

| Goldacre et al (1993)4 | Hospitals within the Oxford Regional Health Authority, UK | 1979–1986 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 26 864 | – | 44 |

| Hayashi et al (2012)35 | Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital, Japan | 2006–2009 | Not specified | Admitted suicidal patients | 3450 | – | 0 |

| Healy et al (2006)36 | Unspecified hospitals, North Wales, UK | 1994–2003 | Coronial records | Psychotic patients | 133 | – | 2 |

| Ho (2003)3 | All psychiatric wards and hospitals in Hong Kong, China | 1997–2000 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 21 921 | – | 124 |

| Isometsa et al (2014)37 | All psychiatric wards and hospitals, Finland | 1987–2004 | Coronial records | Adults with bipolar disorder | 52 747 | 53 | 158 |

| Johansson et al (1996)38 | All psychiatric inpatients in southern Stockholm, Sweden | 1984–1985 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 3862 | 4 | 12 |

| Kessler et al (2015)39 | US Army psychiatric hospitals and wards, USA | 2004–2009 | Coronial records | US army psychiatric patients | 53 769 | 5 | 17 |

| Lee and Lin (2009)40 | All psychiatric wards and hospitals in Taiwan | 2001–2005 | Coronial records | Patients with schizophrenia | 435 | 22 | 39 |

| Links et al (2012)41 | St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada | 2007–2009 | Not specified | Patients with previous suicidal behaviour or ideation | 120 | – | 3 |

| Luxton et al (2013)42 | US Military treatment facilities, USA | 2001–2011 | Coronial records | US service members | 68 947 | – | 35 |

| Madsen and Nordentoft (2013)43 | All psychiatric wards and hospitals in Denmark | 1998–2006 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 287 866 | 175 | 374 |

| Naik et al (1997)44 | Saxondale Hospital, Nottinghamshire, England, UK | 1974–1992 | Local registers and NHS central register | Unselected adults | 86 | – | 0 |

| Nyman and Jonsson (1986)45 |

Unspecified psychiatric hospital, Sweden | 1964–1968 | Coronial records | Patients with schizophrenia | 110 | – | 0 |

| Olfson et al (2016) 46 |

Psychiatric patients from 45 American states | 2001–2008 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 770 643 | 49 | 151 |

| Park et al (2013)47 | Asan Medical Centre, Seoul, South Korea | 1989–2006 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 8403 | 10 | 26 |

| Pedersen et al (2014)48 | All psychiatric hospitals and wards in Denmark | 2005–2010 | Coronial records | Patients with schizophrenia | 7107 | 6 | – |

| Pirkola et al (2007)49 | All psychiatric hospitals and wards in Finland | 1985–2001 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 355 000 | 1164 | 1698 |

| Pokorny (1983)50 | Houston Veterans Administration Medical Centre, Texas, USA | Not specified | Coronial records | Veterans administration patients | 4800 | 10 | 16 |

| Qurashi et al (2006)51 | Unspecified hospital, Manchester, England, UK | Not specified | Not specified | Unselected adults | 69 | 1 | – |

| Riblet et al (2017) 52 |

American Veterans Health Inpatient Mental Health Units | 2002–2015 | Coronial records | Unselected American service-people | 1 126 179 | 141 | – |

| Ruengorn et al (2011)53 | Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand | 2007–2010 | Hospital records | Mood disorder patients admitted for suicide attempt | 235 | 1 | 1 |

| Sani et al (2011)54 | Belvedere Montello Hospital, Rome, Italy | 1964–1998 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 4441 | 2 | – |

| Seemuller et al (2014)55 | Twelve centres across Germany | Not specified | Study follow-up | Patients with major depression | 1014 | 1 | 1 |

| Tejedor et al (1999)56 | Psychiatric Department of Santa Cruz y San Pablo Hospital, Barcelona, Spain | 1983–1997 | Study follow-up | Suicide attempters | 150 | 0 | 1 |

| Tsai et al (2002)57 | Taipei City Psychiatric Centre, Taiwan | 1985–1997 | Coronial records | Patients with mood disorders | 2133 | 0 | 24 |

| Tseng et al (2006)58 | Unspecified psychosomatic ward, Taiwan | 2000–2002 | Study follow-up | Patients with major depression | 67 | 0 | 2 |

| Valenstein et al (2009)59 | All US veteran psychiatric inpatient facilities | 1999–2004 | Coronial data | American veterans with mood disorders | 184 093 | 50 | 127 |

| Winkler et al (2015)60 | All psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric wards, Czech Republic | 2006–2012 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 137 290 | 131 | 258 |

| Yim et al (2004)61 | Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong | 1996–1999 | Coronial records | Unselected adults | 6292 | – | 20 |

NHS, National Health Service.

There were disagreements concerning six of the 68 data points relating to either the number of suicides or the number of patient years. All disagreements were resolved by a second examination of the data by DC and ML.

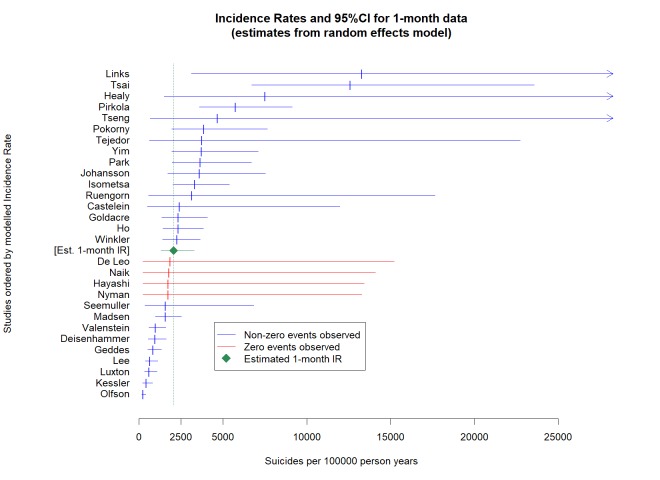

Suicides within a month of discharge

Twenty-nine studies (inclusive of four studies with no suicides) reported 3551 suicides in the first month after discharge during 222 546 person years. The mean number of suicides per study was 122 (SD=443) and the mean number of person years per study was 7674 (SD=22 581). The median sample suicide rate was 2333 per 100 000 person years with a range of 0–30 252 per 100 000 person years. The first and third quartiles were 601 and 4555 per 100 000 person years, respectively (see figure 2. Forest plot of suicide rates in 1 month following discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation.). The pooled rate of 1-month postdischarge suicide was 2060 per 100 000 person years (95% CI=1300 to 3280) with very high between-sample heterogeneity (Q=266.8, p<0.001, I2=90) (table 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of suicide rates in 1 month following discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation.

Table 2.

Suicide rates in the first month postdischarge from psychiatric settings

| N studies | Suicides | Patient years | Pooled estimate | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

| One month | 29 | 3551 | 222 546 | 2060 | 1300 | 3280 |

| Subgroup of studies reporting follow-up at 1 week and 2–4 weeks | ||||||

| One week | 15 | 1928 | 60 854 | 3170 | 1710 | 5890 |

| Two to four weeks | 15 | 1229 | 115 858 | 1060 | 660 | 1070 |

| Subgroup of studies reporting suicides by men and women | ||||||

| Men | 10 | 917 | 83 913 | 1400 | 780 | 2500 |

| Women | 10 | 497 | 82 989 | 720 | 390 | 1320 |

| Subgroup of studies according to data source | ||||||

| Extracted directly | 22 | 2672 | 107 439 | 2880 | 1770 | 4670 |

| Personally communicated | 7 | 879 | 115 107 | 920 | 430 | 1930 |

| Subgroups of studies according to selection for suicidal thoughts or behaviours | ||||||

| Admitted with suicidal thoughts or behaviours | 5 | 5 | 56 | 6210 | 1550 | 24 860 |

| Unselected by suicidally | 24 | 3546 | 222 490 | 1850 | 1170 | 2920 |

| Subgroups of studies according to selection by diagnosis | ||||||

| Patients with a mood disorder | 6 | 312 | 18 201 | 3370 | 1240 | 9180 |

| Patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 3 | 41 | 6270 | 1720 | 330 | 9110 |

| Unselected by diagnosis | 20 | 3198 | 198 075 | 1830 | 1080 | 3110 |

| Subgroups of studies according to study quality | ||||||

| Higher quality* | 8 | 820 | 73 318 | 1360 | 1350 | 1370 |

| Lower quality | 20 | 2731 | 149 227 | 2720 | 2690 | 2740 |

| Subgroup of studies according to geographic region | ||||||

| Asia | 8 | 235 | 13 000 | 3230 | 1470 | 7100 |

| Europe | 10 | 2554 | 75 634 | 2340 | 1170 | 4680 |

| USA | 6 | 346 | 87 376 | 1030 | 450 | 2380 |

| UK, Australia and Canada | 5 | 416 | 46 535 | 2020 | 630 | 6490 |

*One study failed to converge.

Separate data for men and women were available for 10 studies reporting 1-month postdischarge suicides including six studies obtained by personal communication. Men had almost twice the pooled rate of suicide than women (IRR=1.94, 95% CI=1.54 to 2.44; see table 2, online supplementary 5 and 6).

Studies of patients admitted for suicidal thoughts or behaviours had over three times the rate of suicide than studies of psychiatric patients who were not selected in this way (IRR=3.56, 95% CI=1.29 to 7.63), but this result was based on a small number of studies and suicides among patients presenting with suicidal thoughts or behaviours. The analysis of suicide rates according to diagnostic group was also limited by a small number of studies but suggested that groups of patients with a mood disorder might have higher rates of 1-month postdischarge suicide than groups of patients that were not selected by diagnosis (table 2).

The eight studies deemed to be of lower quality had a higher pooled suicide rate compared with the studies deemed to be of higher quality (IRR=1.99, 95% CI=1.98 to 2.01). The eight studies from Asian countries had the highest pooled suicide rate of suicide, followed by the 10 studies from European countries and the five studies from the UK, Canada, and Australia, while the six US studies had the lowest rate (table 2).

Excluding four studies that reported no suicides, 15 studies reported 1-month and 1-week suicides allowing a direct comparison of the suicide rates over the first week postdischarge to the remaining 8–31 days. Among these studies, the 1-week pooled suicide rate was almost three times the rate in the 8–31 days period (IRR=2.99, 95% CI=2.24 to 3.97; see table 2, online supplementary 7 and 8).

Data obtained from direct extraction from published papers had a significantly higher 1-month postdischarge suicide than the data obtained by personal communication (IRR=3.14, 95% CI=1.29 to 7.63). The funnel plot was characterised by eight studies with lower suicide rates than the pooled estimate and five studies with higher suicide rates than the pooled estimate lying outside the funnel (online supplementary 9). An Egger’s test confirmed the likelihood of publication bias towards studies with a higher postdischarge suicide rate (Egger’s bias=4.94, 95% CI=1.38 to 8.50, df=27, p<0.004)

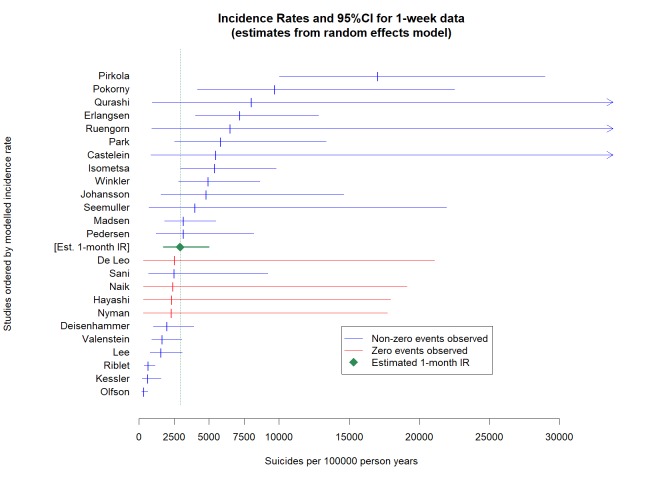

Suicide rates in the first week postdischarge

Twenty-four studies were included in a meta-analysis of 1-week postdischarge suicide rates. These comprised 15 studies reporting suicides at both 1 month and 1 week (as above, table 2), five studies reporting suicides in 1 week but not in 1 month and four studies with no suicides. The 24 studies reported a total of 1928 suicides (mean=80.3 per study, SD=315.5 and median=8) during 60 880 person years (mean=25 360.7 per study, SD=7783 and median=174.5). The median sample suicide rate was 3186 per 100 000 person years (range 0–75 000 per 100 000, first quartile=567 and third quartile=6730).

The pooled 1-month postdischarge suicide rate was 2950 suicides per 100 000 person years (95% CI=1740 to 5000) with very high between-study heterogeneity (Q=186.4, p<0.0001, I2=88). (See table 3, figure 3. Forest plot of suicide rates in 1 week following discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation).

Table 3.

Suicide rates in the week postdischarge from psychiatric settings

| N studies | Suicides | Patient years | Pooled estimate | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

| One week | 24 | 1928 | 60 880 | 2950 | 1740 | 5000 |

| Subgroup of studies according to data source | ||||||

| Extracted directly | 16 | 1429 | 12 605 | 5090 | 2930 | 8840 |

| Personally communicated | 8 | 499 | 48 257 | 1400 | 740 | 2680 |

| Subgroups of studies according to study quality | ||||||

| Higher quality | 5 | 246 | 26 370 | 3950 | 3910 | 3990 |

| Lower quality | 19 | 1682 | 34 492 | 1400 | 1380 | 1410 |

Figure 3.

Forest plot of suicide rates in 1 week following discharge from psychiatric hospitalisation.

Data extracted from published papers had a significantly higher rate of suicide than personally communicated data (IRR=3.63, 95% CI=1.55 to 8.49). The funnel plot was characterised by five studies with lower suicide rates than the pooled estimate and there were four studies with higher suicide rates than the pooled estimate lying outside the funnel (online supplementary 10). An Egger’s test confirmed the likelihood of publication bias towards studies with a higher postdischarge suicide rate (Egger’s bias=4.31, 95% CI=0.85 to 7.78, df=22, p<0.008).

Studies considered to have a lower quality had a higher rate of suicide than those assessed to have a higher quality (IRR=2.83, 95% CI=2.80 to 2.85).

Discussion

This study synthesised over 30 years of research on suicide risk during the period immediately following psychiatric hospitalisation. The study builds on a previous meta-analysis of post psychiatric discharge suicide rates1 by including unpublished data and data that were excluded from an earlier meta-analysis of suicide rates postdischarge1 to estimate suicide rates over the first week and first month postdischarge. One-week postdischarge suicide rates were approximately 3000 suicides per 100 000 person years while 1-month rates were approximately 2000 per 100 000 person years. Rates from the beginning of the second week to the end of the fourth week or 1-month postdischarge were approximately 1000 per 100 000 person years. Rates of 2000–3000 per 100 000 person years are, respectively, about 200–300 times the global suicide rate.10 Our results also compare with a recent meta-analysis that estimated 1132 suicides per 100 000 person years among 18 studies of the first 3 months and 484 per 100 000 person years among 100 studies of any period of follow-up.1 This suggests a sixfold risk of suicide in the first week postdischarge compared with the long-term rates of suicide after psychiatric discharge of about 500 per 100 000 person years. It further suggests that length of time since discharge is at least as important as clinical risk factors for suicide (OR=1.50)11 and high-risk models for suicide (OR=4.84)12 reported in longitudinal studies.13

Our finding of higher rates of suicides by men in the immediate postdischarge period is unsurprising because of the preponderance of men among all suicide deaths,10 but is in contrast with less clear gender effects on inpatient suicide rates.14 15

The main limitation of our study is uncertainty about the extent to which our pooled estimates can be generalised. We observed very high between-study heterogeneity that may be partially explained by publication bias towards studies with high suicide rates and aspects of study quality. However, in all likelihood, there are real differences in postdischarge suicide rates between settings that cannot be examined using the existing literature. Most importantly, this study was not able to ascertain the role of the availability and the quality of postdischarge care in determining postdischarge suicide rates.

Our findings emphasise the importance of postdischarge follow-up. Currently, in the USA, only around half of the commercially insured patients and a third of Medicare patients received a psychiatric follow-up visit within 7 days of hospital discharge for a mental illness.16 In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines suggest that people discharged from mental health settings should be followed-up within 7 days.17 While the introduction of a 7-day follow-up period is one of a suite of measures that do seem to be associated with lower suicide rates in the UK,18 it is sobering to consider that some patients who are scheduled to be followed-up at the 7-day mark will die before they are ever reassessed.

Very high rates of suicide in the immediate postdischarge period should encourage clinicians to think carefully about the patient’s transition from hospital to the community. Qualitative research suggests that the transition from hospital to home is associated with re-emergence of pre-existing social stresses and new stresses associated with hospitalisation.19–21 Clinicians should consider strategies that might improve this transition, including predischarge and postdischarge patient psychoeducation, formal needs-based assessments, use of transitional care teams, improved communication between the inpatient team and greater involvement of the patient’s outpatient team and family.22

The high risk of suicide during the period immediately following hospital discharge provides a clinical rationale for conceptualising the first postdischarge month as a distinct phase of recovery and treatment, especially in the context of pervasive gaps in treatment following psychiatric hospitalisation. Traditional case management approaches to the continuity of care following psychiatric hospitalisation have not consistently yielded promising results. In one review, two of seven studies of telephone follow-up and one of five studies that involved facilitating communication between inpatient and outpatient clinicians resulted in a significant increase in continuity of care.22 Intensive interventions that involve home visits, social support, motivational interviewing and accompanying patients to outpatient appointments have yielded more encouraging results.23 24

Other limitations relate to the representativeness of the included studies. All of the research came from high-income economies of Asia, Australasia, North America and Europe, and our results might not be representative of postdischarge suicide in low-income and middle-income countries. Moreover, there were an insufficient number of studies to determine whether apparent differences in suicide rates between regions were real or simply the result of available studies. Differences between rates of postdischarge suicide between countries are plausible because of differences in national suicide rates,10 progress towards deinstitutionalisation25 and likely national differences in the quality of mental healthcare systems26.

Although it has been argued that one way of combatting postdischarge suicide is to focus on individual patients with clinical characteristics that signify a high suicide risk,27 28 the very high suicide rates calculated in this study and the known limitations of suicide risk assessment29 suggest that a narrow focus on clinical risk assessment might mislead clinicians into thinking that some recently discharged psychiatric inpatients can be regarded as being at low risk postdischarge.30 Our findings support an approach to suicide prevention focused on whole cohorts of discharged patients.13

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following authors who provided further information about their published studies of suicide after psychiatric hospitalisation: Dr Ebehard Deisenhammer, Dr Erkki Isometsa, Dr Ron Kessler, Dr Edith Liemburg, Dr Natalie Riblet and Dr Marcia Valenstein.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design: DC and ML. Data collection: DC, ML, MO, SS and MW. Data analysis: DH-P and ML. Interpretation and critical review: ML, MO and DH-P. Manuscript preparation: DC, DH-P, ML, MO, SS and MW.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MO reports grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the data are reported in supplementary materials.

Author note: ML has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:694–702. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Large MM. The role of prediction in suicide prevention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2018;20:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho TP. The suicide risk of discharged psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:702–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldacre M, Seagroatt V, Hawton K. Suicide after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care. Lancet 1993;342:283–6. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91822-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geddes JR, Juszczak E. Period trends in rate of suicide in first 28 days after discharge from psychiatric hospital in Scotland, 1968-92. BMJ 1995;311:357–60. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. PROSPERO. International prospective register of systematic reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/

- 7. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connnell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp

- 10. World Health Organisation. Age-standardized suicide rates (per 100 000 population). 2015. http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates/en/ (Accessed October 2015).

- 11. Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 2017;143:187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Large M, Kaneson M, Myles N, et al. Meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies of suicide risk assessment among psychiatric patients: heterogeneity in results and lack of improvement over time. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156322 10.1371/journal.pone.0156322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Bridge JA. Focusing suicide prevention on periods of high risk. JAMA 2014;311:1107–8. 10.1001/jama.2014.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Large M, Myles N, Myles H, et al. Suicide risk assessment among psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-risk categories. Psychol Med 2018;48:1119–27. 10.1017/S0033291717002537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:18–29. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. NCQA. Follow-up after hospitalisation for Mental Illness: National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. NICE. Transition between inpatient mental health settings and community or care home settings: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A, et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997-2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet 2012;379:1005–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Owen-Smith A, Bennewith O, Donovan J, et al. "When you’re in the hospital, you’re in a sort of bubble." Understanding the high risk of self-harm and suicide following psychiatric discharge: a qualitative study. Crisis 2014;35:154–60. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Large MM. Commentary: adverse experiences in psychiatric hospitals might be the cause of some postdischarge suicides. Bull Menninger Clin 2016;80:371–5. 10.1521/bumc.2016.80.4.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schechter M, Goldblatt MJ, Ronningstam E, et al. Postdischarge suicide: a psychodynamic understanding of subjective experience and its importance in suicide prevention. Bull Menninger Clin 2016;80:80–96. 10.1521/bumc.2016.80.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Dennis CL, et al. Transitional interventions to reduce early psychiatric readmissions in adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:187–94. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.115030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, et al. Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:451–8. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shaffer SL, Hutchison SL, Ayers AM, et al. Brief critical time intervention to reduce psychiatric rehospitalization. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:1155–61. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor Salisbury T, Killaspy H, King M. An international comparison of the deinstitutionalisation of mental health care: Development and findings of the Mental Health Services Deinstitutionalisation Measure (MENDit). BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:54 10.1186/s12888-016-0762-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spaeth-Rublee B, Pincus HA, Silvestri F, et al. Measuring quality of mental health care: an international comparison. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:10384–9. 10.3390/ijerph111010384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2014;44:432–43. 10.1111/sltb.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet 2016;387:1227–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryan CJ, Large MM. Suicide risk assessment: where are we now? Med J Aust 2013;198:462–3. 10.5694/mja13.10437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nordentoft M, Erlangsen A, Madsen T. Postdischarge suicides: nightmare and disgrace. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:1113–4. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castelein S, Liemburg EJ, de Lange JS, et al. Suicide in recent onset psychosis revisited: significant reduction of suicide rate over the last two decades - a replication study of a dutch incidence cohort. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129263 10.1371/journal.pone.0129263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Leo D, Heller T. Intensive case management in suicide attempters following discharge from psychiatric care. Aust J Prim Health 2007;13:49–58. 10.1071/PY07038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deisenhammer EA, Behrndt EM, Kemmler G, et al. A comparison of suicides in psychiatric in-patients, after discharge and in not recently hospitalized individuals. Compr Psychiatry 2016;69:100–5. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Tu X, et al. Suicide among older psychiatric inpatients: an evidence-based study of a high-risk group. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:734–41. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000225084.16636.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hayashi N, Igarashi M, Imai A, et al. Post-hospitalization course and predictive signs of suicidal behavior of suicidal patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital: a 2-year prospective follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:1 10.1186/1471-244X-12-186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Healy D, Harris M, Tranter R, et al. Lifetime suicide rates in treated schizophrenia: 1875-1924 and 1994-1998 cohorts compared. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:223–8. 10.1192/bjp.188.3.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Isometsä E, Sund R, Pirkola S. Post-discharge suicides of inpatients with bipolar disorder in Finland. Bipolar Disord 2014;16:867–74. 10.1111/bdi.12237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansson LM, Johansson S-E, Sundquist J, et al. Suicide among psychiatric in-patients in Stockholm, Sweden. Archives of Suicide Research 1996;2:171–81. 10.1080/13811119608258999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, et al. Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study To Assess Risk and rEsilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:49–57. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee HC, Lin HC. Are psychiatrist characteristics associated with postdischarge suicide of schizophrenia patients? Schizophr Bull 2009;35:760–5. 10.1093/schbul/sbn007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Links P, Nisenbaum R, Ambreen M, et al. Prospective study of risk factors for increased suicide ideation and behavior following recent discharge. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:88–97. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luxton DD, Trofimovich L, Clark LL. Suicide risk among US Service members after psychiatric hospitalization, 2001-2011. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:626–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Madsen T, Nordentoft M. Changes in inpatient and postdischarge suicide rates in a nationwide cohort of Danish psychiatric inpatients, 1998-2005. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e1190–4. 10.4088/JCP.13m08656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Naik PC, Davies S, Buckley AM, et al. Long-term mortality after first psychiatric admission. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:43–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nyman AK, Jonsson H. Patterns of self-destructive behaviour in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986;73:252–62. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Short-term suicide risk after psychiatric hospital discharge. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:1119–26. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Park S, Choi JW, Kyoung Yi K, et al. Suicide mortality and risk factors in the 12 months after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care in Korea: 1989-2006. Psychiatry Res 2013;208:145–50. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pedersen CG, Jensen SO, Gradus J, et al. Systematic suicide risk assessment for patients with schizophrenia: a national population-based study. Psychiatr Serv 2014;65:226–31. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pirkola S, Sohlman B, Heilä H, et al. Reductions in postdischarge suicide after deinstitutionalization and decentralization: a nationwide register study in Finland. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:221–6. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.2.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qurashi I, Kapur N, Appleby L. A prospective study of noncompliance with medication, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior in recently discharged psychiatric inpatients. Arch Suicide Res 2006;10:61–7. 10.1080/13811110500318455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Riblet N, Shiner B, Watts BV, et al. Death by suicide within 1 week of hospital discharge: a retrospective study of root cause analysis reports. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017;205:436–42. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ruengorn C, Sanichwankul K, Niwatananun W, et al. Incidence and risk factors of suicide reattempts within 1 year after psychiatric hospital discharge in mood disorder patients. Clin Epidemiol 2011;3:305–13. 10.2147/CLEP.S25444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sani G, Tondo L, Koukopoulos A, et al. Suicide in a large population of former psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;65:286–95. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Seemüller F, Meier S, Obermeier M, et al. Three-Year long-term outcome of 458 naturalistically treated inpatients with major depressive episode: severe relapse rates and risk factors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;264:567–75. 10.1007/s00406-014-0495-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tejedor MC, Díaz A, Castillón JJ, et al. Attempted suicide: repetition and survival-findings of a follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;100:205–11. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tsai SY, Kuo CJ, Chen CC, et al. Risk factors for completed suicide in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:469–76. 10.4088/JCP.v63n0602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tseng MC, Cheng IC, Lee YJ, et al. Intermediate-term outcome of psychiatric inpatients with major depression. J Formos Med Assoc 2006;105:645–52. 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ganoczy D, et al. Higher-risk periods for suicide among VA patients receiving depression treatment: prioritizing suicide prevention efforts. J Affect Disord 2009;112:50–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Winkler P, Mladá K, Csémy L, et al. Suicides following inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: a nationwide case control study. J Affect Disord 2015;184:164–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yim PH, Yip PS, Li RH, et al. Suicide after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: a case-control study in Hong Kong. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004;38:65–72. 10.1177/000486740403800103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023883supp001.pdf (767.9KB, pdf)