Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence and factors associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among older adults in an urban area of South India.

Setting

The study was conducted in the capital city of Thiruvananthapuram in the South Indian state of Kerala.

Participants

The study participants were community-dwelling individuals aged 60 years and above.

Primary outcome measure

MCI was the primary outcome measure and was defined using the criteria by European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium. Cognitive assessment was done using the Malayalam version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination tool. Data were also collected on sociodemographic variables, self-reported comorbidities like hypertension and diabetes, lifestyle factors, depression, anxiety and activities of daily living.

Results

The prevalence of MCI was found to be 26.06% (95% CI of 22.12 to 30.43). History of imbalance on walking (adjusted OR 2.75; 95 % CI of 1.46 to 5.17), presence of depression (adjusted OR 2.17, 95 % CI of 1.21 to 3.89), anxiety (adjusted OR 2.22; 95 % CI of 1.21 to 4.05) and alcohol use (adjusted OR 1.99; 95 % CI of 1.02 to 3.86) were positively associated with MCI while leisure activities at home (adjusted OR 0.33; 95 % CI of 0.11 to 0.95) were negatively associated.

Conclusion

The prevalence of MCI is high in Kerala. It is important that the health system and the government take up urgent measures to tackle this emerging public health issue.

Keywords: elderly, mild cognitive impairment, dementia

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is the first study of its kind in Kerala and has estimated the burden of mild cognitive impairment in an urban setting using locally validated tool.

The study has used adequate sample size.

Depression and anxiety were assessed using Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale which is a screening tool and does not provide confirmatory diagnosis of these disorders.

The diagnosis of dementia was not confirmed by neurologist in the present study.

Introduction

Advancing age is associated with changes in cognitive ability.1 Dementia, which is the pathological extremity of cognitive impairment, is a major cause of morbidity and dependency among older adults. WHO in 2012 has identified dementia as a public health priority and has developed the global action plan on the public health response to dementia (2017–2025) to reduce its impact on individuals and communities.2 3 Globally, there were 35.6 million people living with dementia in 2012. Developing countries account for nearly 60% of this burden, with India and China together contributing to more than one-fourth of the global burden.4 5 India is predicted to have a 300% increase in the prevalence of dementia from 2001 to 2040.5 Kerala, which is the fastest ageing state in India will have significant contribution to this increase.6 It is projected that by midcentury, 35% of Kerala’s population will be older than 60 years.7 This will lead to an unprecedented increase in cognitive disorders, with overwhelming impact on caregivers, health sector, society and the government.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a diagnostic entity used to describe cognitive impairment in non-demented people. The concept of MCI was introduced by Petersen in 1997.8 It refers to a transitional stage in the cognitive continuum from normal ageing to pathological ageing, where people experience cognitive decline greater than that is expected for the age, yet do not meet the criteria for the diagnosis of dementia.8–11 People with MCI are at 10 times higher risk of developing dementia than cognitively healthy older adults.10 12 In addition to increased risk of dementia, these people have more than twice the risk of all-cause mortality compared with those with normal cognition.13

The prevalence of MCI reported from different regions of the world varies widely between 3% and 42%.14 Previously published studies from India estimate prevalence between 15% and 33%.15–17 This wide variation in estimates could be due to differences in MCI definitions, the age structure of population or assessment tools used.14

Various sociodemographic, physical and psychological factors have been found to be associated with MCI. Advancing age,18 male gender,16 low socioeconomic status, low levels of education and manual labour have been identified as risk factors in different settings.19 Patients with diabetes mellitus20 and hypertension21 are at increased risk of developing MCI. Neuropsychiatric disorders like anxiety and depression also predispose older adults to develop MCI later in life.22 Increasing years of schooling18 and socialisation23 have been reported as protective against MCI.

There is increasing evidence on the burden and risk factors for cognitive impairment in the recent years, but most of these have been published from Western countries. The 10/66 dementia studies among few others focus on cognitive disorders in low/middle-income countries (LMICs), but they either report prevalence of specific subtypes of MCI or give general estimates for the LMICs rather than country-specific estimates.16 24 The literature on the burden assessment or characterisation of MCI in Kerala is very limited. Even though a few studies have assessed the dementia prevalence in Kerala, there has been none on MCI.25 26 The existing evidences of MCI prevalence in India are based on North Indian populations, which are very different from Kerala in terms of ageing trends and sociodemographic profile.15

In the context of rapid ageing in Kerala, it is important to bridge this research gap. This study was undertaken to assess the prevalence of MCI and to study the factors associated with MCI in older individuals in an urban area of Kerala, India. The results obtained from the study can provide valuable inputs for planning healthcare services of older individuals in similar settings.

Methodology

This was a community-based, cross-sectional study undertaken in the population under Medical College Health Unit, Pangappara, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, in South India, between October 2012 and January 2014. The health unit caters to an urban area with a population of 113 000. The area under the centre is divided into 10 subcentres (peripheral most health service units under the Department of Health). The study population included community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and above in this area. Individuals with severe visual and hearing impairment and those not willing to consent were excluded from the study. Based on an expected prevalence of 33%,17 alpha error of 5%, relative precision of estimate as 20% and design effect of 2, the sample size was calculated as 426. Relative precision was taken as 20% of prevalence (=6.6), since the power of the study was fixed at 80%. The number of clusters was arbitrarily fixed as 20. A cluster was defined as a group of 21 older adults. These clusters were chosen from the 10 subcentre areas by probability proportionate to the population size of the subcentres, that is, subcentres with larger population had more clusters sampled from them. Twenty-one participants from each cluster were chosen by proximity method. Twenty clusters each with 21 participants yielded a sample size of 420. An additional of one sample each was taken from the first six clusters to meet the estimated sample size of 426. Ethics clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

Study variables

Sociodemographic variables

Age, sex, education (years of schooling), socioeconomic status based on ration cards (classified as above poverty line and below poverty line), occupation (currently employed, pensioner or unemployed), marital status, type of family (nuclear or joint) and living arrangement.

Lifestyle factors

Regular physical activity (for 30 min a day for at least 5 days a week), alcohol use (ever users or never users), tobacco use (smoked and non-smoked tobacco-ever users or never users), current engagement in leisure activities at home (reading books, reading newspapers, participation in games, watching TV, gardening, listening to music or any other activities during leisure)

Comorbidities

History of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, hearing and visual problems, imbalance on walking and serious head injury (requiring admission and treatment) were collected from the participant or the relative. Depression was defined as a score of 7 or more in depression subscale of Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) and anxiety as a score of 9 or more in the anxiety subscale of HADS.27

MCI

MCI in the study was assessed using the definition of European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium in June 2005.28 Participants who met all the five criteria of this definition were defined as MCI cases.The assessment method used for each criterion is given in table 1. Based on the cognitive features, MCI was categorised into single-domain amnestic (only memory domain affected), multiple-domain amnestic (multiple domains affected, including memory), single-domain non-amnestic (single domain other than memory affected) and multiple-domain non-amnestic (multiple domains affected, not including memory). Dementia was assessed using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria.29

Table 1.

Definition of MCI by EADC in 2005 and the instruments and cut-offs used for its assessment in the study

| MCI definition criteria | Instrument used | Assessment cut-off adopted in the study |

| 1. Cognitive complaints coming from the patients or their families 2. Reporting of a relative decline in cognitive functioning during the past year by the patient or informant |

History from the patient or bystander | |

| 3. Cognitive disorders as evidenced by clinical evaluation | Malayalam version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (m-ACE).47 | Score below the cut-off in at least one of the seven cognitive domains assessed. [One SD below the mean score (of that educational category) was taken as the cut-off for each domain] |

| 4. Absence of major repercussions on daily life | Everyday Ability Scale for India (EASI) | 95th percentile of EASI scores of subjects with no subjective or objective cognitive decline in the study sample was taken as cut-off. This was 2; a score up to 2 was taken as normal activities of daily living. |

| 5. Absence of dementia | DSM IV criteria | Patients not satisfying this criteria |

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; EADC, European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Patient and public involvement

Participants were not directly involved in the development of the study. However, the authors received input from Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA workers) regarding participant priorities and preferences on outcome measurement. ASHA workers are community health workers who are local residents and are the key communication mechanism between population and healthcare services. Their opinions in health-related matters reflect the needs and preferences of the community they serve.

Data collection

Data were collected by trained interviewer by visiting the participants in their home. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants (or relatives) before collecting data. All interviews were conducted by a physician researcher who was trained in administering the neuropsychiatric inventory, at the Department of Neurology in Government Medical College Trivandrum.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS V.20.0.30 Quantitative variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean and SD and categorical variables as frquency and percentage. Bivariate statistical inference was done using independent t-test (quantitative) and χ2 (categorical variables). Binary logistic regression was used to find out the factors associated with MCI. Purposeful selection of variables was conducted to create final regression model.31

Results

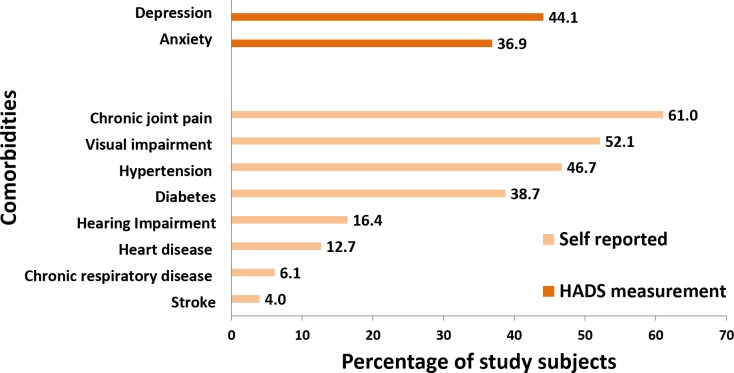

Four hundred and forty-four eligible participants were approached for the interview, out of which 426 participated. The non-response rate was 4%. The baseline characteristics of the 426 subjects included in analysis are given in table 2. The mean age of the study participants was 69.9 (SD 7.9) years. Women formed majority of study participants (62%). As evident from figure 1, the most common self-reported comorbidity was chronic joint pain (61%), followed by visual impairment (52.1%). Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were reported by 46.7% and 38.7% of the subjects, respectively. The proportion of study participants with depression and anxiety as assessed by HADS was 44.1% and 36.9%, respectively.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n=426)

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (percentage) |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||

| Age in years | 60–69 | 229 (53.8) |

| 70 and above | 197 (46.2) | |

| Gender | Males | 160 (38) |

| Females | 266 (62) | |

| Years of education | ≤ 8 | 248 (58.2) |

| Mean (SD)=6.78 (4) | >8 | 178 (41.8) |

| Marital status | Currently married | 275 (64.6) |

| Widowed/separated/ unmarried |

151 (35.4) | |

| Occupation | Pensioner | 127 (29.8) |

| Currently employed | 43 (10.1) | |

| Unemployed | 136 (31.9) | |

| Home maker | 120 (28.2) | |

| Socioeconomic status | APL | 303 (71.1) |

| BPL | 123 (28.9) | |

| Living arrangement | With spouse | 237 (55.6) |

| Relative other than spouse | 164 (38.5) | |

| Alone | 25 (5.9) | |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Alcohol user (Men n=160) | Ever users | 81 (50.6) |

| Never users | 79 (49.4) | |

| Alcohol use (Women n=266) | Ever users | 0 (0) |

| Never users | 266 (100) | |

| Tobacco use (Men n=160) | Ever users | 86 (53.8) |

| Never users | 74 (46.2) | |

| Tobacco use (Women n=266) | Ever users | 48 (18) |

| Never users | 218 (82) | |

| Had regular physical activity | Yes | 120 (28.2) |

APL, above poverty line; BPL, below poverty line.

Figure 1.

Proportion of study subjects with comorbidities (n=426). HADS, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale.

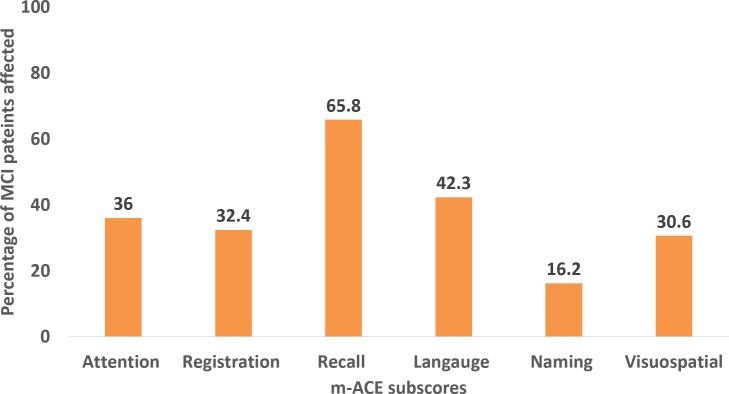

Six patterns of cognitive status (A, B, C, D, E and F) were observed among the study participants (table 3). These patterns ranged in a cognitive spectrum from normal cognition to dementia as depicted in figure 2. Pattern A was normal cognition, while patterns D and F corresponded to MCI and dementia, respectively. The prevalence of MCI was obtained as 26.06% (95 % CI 22.12 to 30.43). Dementia was identified in 24 out of the 426 participants (5.63%).

Table 3.

Patterns of cognitive status observed based on the cognitive assessment tools used in the study

| Criteria assessed | Subjective evidence of cognitive decline | Objective evidence of cognitive decline | Abnormal activities of daily living | Satisfies diagnostic criteria for dementia |

| Method of assessment | Positive history of cognitive decline from the patient or the bystander | An abnormal score in any of the domains of cognition in Malayalam version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination | An Everyday Abilities Scale for India score of more than 2 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria |

| Patterns of cognition | ||||

| A-Normal | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| B | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| C | Absent | Present | Absent | Absent |

| D-Mild cognitive impairment | Present | Present | Absent | Absent |

| E | Present | Present | Present | Absent |

| F- Dementia | Present | Present | Present | Present |

Figure 2.

Spectrum of cognitive pattern of the study participants (n=426).

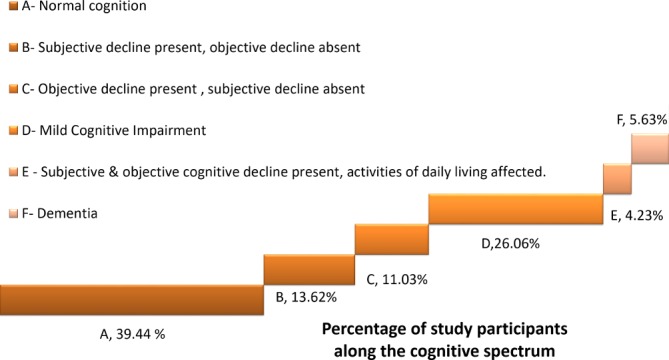

As shown in figure 3, 56.8% of the patients with MCI were in the age group 60 to 69 years, and 60.4% of them were women. Memory was affected in 65.8%of the MCI cases (amnestic MCI). The most common subtype of MCI was multiple-domain amnestic (55.9% of the MCI cases) (figure 3). Figure 4 shows the proportion of MCI cases with abnormal scores in various subscores of Malayalam version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (m-ACE). Recall and language were the subscores affected in maximum number of participants.

Figure 3.

Distribution of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases (n=111) by age, gender and type of MCI.

Figure 4.

Proportion of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases showing decline in various sub scores of Malayalam version of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (m-ACE) (n=111).

Patients with MCI (pattern D, n=111) were compared with those with normal cognition (pattern A, n=168) to evaluate the factors associated with MCI (table 4). All variables having p value of less than 0.2 in bivariate inference testing were entered as independent variables in the logistic regression model. The variables which showed positive association with MCI, adjusting for covariates, were imbalance on walking (adjusted OR 2.75; 95% CI 1.46 to 5.17), depression (adjusted OR 2.17; 95% CI 1.21 to 3.89), anxiety (adjusted OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.21 to 4.05), current or previous use of alcohol (adjusted OR 1.99; 95% CI 1.02 to 3.86). Leisure activities at home (adjusted OR 0.33; 95% CI 0.11 to 0.95) showed negative association with MCI.

Table 4.

Factors associated with MCI: result of bivariate and logistic regression analyses

| Determinants of MCI | MCI (pattern D, n=111) | Normal cognition (pattern A, n=168) | χ2 test | |

| Factors | P value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 60–69 | 63 (56.8) | 102 (60.7) | 0.658 | 0.85 (0.52 to 1.38) |

| ≥ 70 | 48 (43.2) | 66 (39.3) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44 (39.6) | 63 (37.5) | 0.719 | 1.09 (0.67 to 1.79) |

| Female | 67 (60.4) | 105 (62.5) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| APL | 72 (64.9) | 123 (73.2) | 0.137 | 0.68 (0.40 to 1.13) |

| BPL | 39 (35.1) | 45 (26.8) | ||

| No. of years of education | ||||

| ≤8 years | 68 (61.3) | 89 (53) | 0.172 | 1.40 (0.86 to 2.29) |

| >8 years | 43 (38.7) | 79 (47) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently married | 72 (64.9) | 115 (68.5) | 0.533 | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.41) |

| Widowed/unmarried/separated | 39 (35.1) | 53 (31.5) | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Currently employed/pensioner | 43 (38.7) | 72 (42.9) | 0.494 | 0.84 (0.52 to 1.38) |

| Unemployed | 68 (61.3) | 96 (57.1) | ||

| Presence of diabetes mellitus | 41 (36.9) | 58 (34.5) | 0.68 | 1.11 (0.67 to 1.83) |

| Presence of hypertension | 54 (48.6) | 72 (42.9) | 0.341 | 1.26 (0.78 to 2.04) |

| Presence of ischaemic heart disease | 12 (10.8) | 20 (11.9) | 0.779 | 0.90 (0.42 to 1.92) |

| Presence of imbalance on walking | 40 (36) | 26 (15.5) | <0.001 | 3.08 (1.74 to 5.44) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Ever users | 26 (23.4) | 26 (15.5) | 0.095 | 1.67 (0.91 to 3.06) |

| Never users (ref) | 85 (76.6) | 142 (84.5) | ||

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Ever users | 39 (35.1) | 45 (26.8) | 0.137 | 1.48 (0.88 to 2.49) |

| Never users(ref)) | 72 (64.9) | 123 (73.2) | ||

| Has adequate physical activity | 27 (24.3) | 59 (35.1) | 0.056 | 0.59 (0.35 to 1.02) |

| Has at least one leisure activity at home | 84 (75.7) | 141 (83.9) | 0.088 | 0.59 (0.33 to 1.08) |

| Presence of depression | 67 (60.4) | 54 (32.1) | <0.001 | 3.22 (1.95 to 5.30) |

| Presence of anxiety | 60 (54.1) | 40 (23.8) | <0.001 | 3.77 (2.25 to 6.30) |

| Logistic regression | |||

| Determinants of MCI | p value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI of adjusted OR |

| Presence of imbalance on walking | 0.002 | 2.75 | 1.46 to 5.17 |

| Alcohol use (ever users vs never users) | 0.043 | 1.99 | 1.02 to 3.86 |

| Has at least one leisure activity at home | 0.041 | 0.33 | 0.11 to 0.95 |

| Presence of depression | 0.009 | 2.17 | 1.21 to 3.89 |

| Presence of anxiety | 0.01 | 2.22 | 1.21 to 4.05 |

*Final model with all significant variables.

APL,above poverty line; BPL, below poverty line; MCI, mild cognitive impairment

Discussion

The prevalence of MCI in urban Kerala was 26.06%. While this is comparable to the rates in some developed regions of the world, it is higher than the prevalence reported from other parts of India.32–34 Studies conducted among North Indian and East Indian older individuals using Kolkata cognitive screening battery have reported prevalence of 19.26% and 14.9%, respectively.15 35 This difference in prevalence could probably be due to the difference in study population and the definitions used. The study in Kolkata enrolled subjects aged 50 years and above who were free of depression. In fact, even in the current study, the proportion of MCI cases among non-depressed subjects was 18.5%. The lack of a standardised tool or instrument for diagnosing MCI makes the comparisons across various settings difficult.

As evident from figure 2, only less than 40% of the participants had normal level of cognition. Six out of ten older adults had some form of cognitive impairment. Around 10% of the study participants had cognitive impairment affecting activities of daily living. All these findings point to the fact that there is a substantial and largely unidentified need for care of older adults with cognitive impairment in urban Kerala. The government of Kerala has launched an initiative called Vayomithram, through which mobile clinics offer home-based healthcare, palliative and counselling services to older adults.36 Community-based care of patients with severe cognitive impairment can be integrated into these services.

In addition to the normal cognition, MCI (group D) and dementia (group F), three additional cognitive patterns were observed in the study. Subjects categorised as groups B and C have a level of cognition between normal cognition and MCI, while group E lies between MCI and dementia. This observation is a pointer to the concept of transitional stage between normal and pathological ageing which needs to be further explored.

Two-thirds of the MCI cases were amnestic. Studies in Beijing and the Einstein Ageing study have also reported similar findings.37 38 Multiple domain amnestic MCI was identified as the the most common subtype in the present study. Knowing this pattern helps to better target prevention and early detection strategies.

MCI patients had a higher proportion of diabetes mellitus and hypertension compared with those with normal cognition, but these were not statistically significant. The positive factors associated with MCI were history of imbalance on walking, presence of depression, anxiety and current or previous use of alcohol. Various studies have shown objective gait assessment as an effective screening method for early detection of MCI.39 40 The current study has shown that even history of imbalance reported by the patient can be used for early detection of cognitive impaiment. Studies from across the world have shown that depression and anxiety are risk factors for MCI.22 38 41 The present study gives evidence to support these findings. In fact, depression and anxiety assessed using a single scale (HADS) could be used as screening tool to identify older adults at risk of MCI. However as with Alzheimer’s disease, depression and anxiety might be the manifestations of shared brain pathology of MCI patients.

Leisure activity at home was found to be protective against MCI, compared with not having any activities during leisure. This is similar to findings from the Mayo Clinic Study of Ageing in Minnesota, that reading books and engaging in craft work are protective against MCI.42 Even though leisure activities at home were protective, the present study could not elicit a protective association of MCI with social activities outside home.

The results of various studies evaluating the association of alcohol with cognitive impairment have been inconclusive, equivocal and contradicting. This study has observed alcohol use being positively associated with MCI. Certain studies have observed a U-shaped curve where non-users and frequent or heavy users of alcohol had twofold risk of developing MCI compared with infrequent or moderate users.43 44 The variability of findings might be due to interaction with age, gender, other lifestyle factors or difference in drinking patterns. Our study did not analyse the duration, pattern or type of alcohol use. Alcoholism is a public health problem in Kerala, where 45% of adult men and 14% of older men are alcohol users.45 In a population with such a high prevalence of alcohol use, this association should be considered significant in the epidemiology of dementia and needs to be evaluated further in future studies.

Conclusion

The burden of MCI in Kerala is high and will contribute to the increasing burden of dementia. The study indicates that gait imbalance, depression and anxiety are positively associated with MCI. These factors could be targeted in future studies to develop prevention and screening strategies for detection of early stages of cognitive decline in older individuals. The study also throws light on the transitional stages of cognitive decline between normal and dementia. Further studies need to be undertaken to characterise these entities.

Limitation

Depression and anxiety were assessed using HADS which is a screening tool and does not provide confirmatory diagnosis of these disorders. However, psychiatrist diagnosis is not cost-effective for community-based studies in LMIC. Use of valid screening tools which can be administered by peripheral healthcare workers are justifiable to increase the detection rates in the community. The diagnosis of dementia was not confirmed by a neurologist in the present study, but the estimates were comparable to other studies in the same setting.46 Third, the study did not assess the duration and quantity of alcohol use. Future analytical studies should be designed to better evaluate the association of these factors with MCI and its progression to dementia. Although controlled for some known confounders, there may be additional confounders that are unaccounted for in our analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support given by the field staff and ASHA workers of urban health training center Pangappara, Government Medical College Thiruvananthapuram, in the conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: DM and TI conceived the research idea. SV and AU contributed to refinement of idea. DM conducted the analysis and prepared the first draft. TI, SV, AU and MM contributed to the subsequent drafts. All the authors agreed to the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Christensen H. What cognitive changes can be expected with normal ageing? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35:768–75. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organistaion and Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: A public health priority. Geneva, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organisation. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rao GN, Bharath S. Cost of dementia care in India: delusion or reality? Indian J Public Health 2013;57:71–7. 10.4103/0019-557X.114986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ministry of Home Affairs GoI. SRS Statistical Report 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Commission P. Kerala Development Report. New Delhi: Academic Foundation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Aging, memory, and mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9 Suppl 1:65–9. 10.1017/S1041610297004717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1985–92. 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183–94. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. The Lancet 2006;367:1262–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rubin EH, Storandt M, Miller JP, et al. A prospective study of cognitive function and onset of dementia in cognitively healthy elders. Arch Neurol 1998;55:395–401. 10.1001/archneur.55.3.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katz MJ, Wang C, Hall C, et al. Mortality associated with amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment in a community based population: Results from the Einstein Aging Study (EAS). Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2010;6:S454–S455. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.05.1515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ward A, Arrighi HM, Michels S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: disparity of incidence and prevalence estimates. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:14–21. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Das SK, Bose P, Biswas A, et al. An epidemiologic study of mild cognitive impairment in Kolkata, India. Neurology 2007;68:2019–26. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264424.76759.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sosa AL, Albanese E, Stephan BC, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and impact of mild cognitive impairment in Latin America, China, and India: a 10/66 population-based study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001170 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swarnalatha N. Cognitive status among rural elderly women. Journal of the Indian Academy of Geriatrics 2007;3:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Afgin AE, Massarwa M, Schechtman E, et al. High prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in arabic villages in northern Israel: impact of gender and education. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;29:431–9. 10.3233/JAD-2011-111667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marengoni A, Fratiglioni L, Bandinelli S, et al. Socioeconomic status during lifetime and cognitive impairment no-dementia in late life: the population-based aging in the Chianti Area (InCHIANTI) Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;24:559–68. 10.3233/JAD-2011-101863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Patel B, et al. Relation of diabetes to mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2007;64:570–5. 10.1001/archneur.64.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reitz C, Tang MX, Manly J, et al. Hypertension and the risk of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1734–40. 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geda YE, Roberts RO, Mielke MM, et al. Baseline neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:572–81. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13060821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson ND, Murphy KJ, Troyer AK. Living with mild cognitive impairment: A guide to maximizing brain health and reducing risk of dementia: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Lara E, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and physical activity in the general population: Findings from six low- and middle-income countries. Exp Gerontol 2017;100:100–5. 10.1016/j.exger.2017.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaji S, Bose S, Verghese A. Prevalence of dementia in an urban population in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:136–40. 10.1192/bjp.186.2.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shaji S, Promodu K, Abraham T, et al. An epidemiological study of dementia in a rural community in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry 1996;168:745–9. 10.1192/bjp.168.6.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Portet F, Ousset PJ, Visser PJ, et al. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in medical practice: a critical review of the concept and new diagnostic procedure. Report of the MCI Working Group of the European Consortium on Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:714–8. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.085332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30. SPSS Inc. IBM SPSS statistics base 20. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, et al. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008;3:17 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hänninen T, Hallikainen M, Tuomainen S, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study in elderly subjects. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;106:148–54. 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.01225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: data from the Indianapolis Study of Health and Aging. Neurology 2001;57:1655–62. 10.1212/WNL.57.9.1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol 2008;63:494–506. 10.1002/ana.21326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh VB. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in elderly population of North India. https://www.alz.co.uk/sites/default/files/conf2013/oc004.pdf (accessed 02 Nov 2018).

- 36. Kerala Go. Palliative Care 2017. https://kerala.gov.in/palliative-care (accessed 9 Feb 2018).

- 37. Li X, Ma C, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence of and potential risk factors for mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling residents of Beijing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:2111–9. 10.1111/jgs.12552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nair V, Ayers E, Noone M, et al. Depressive symptoms and mild cognitive impairment: results from the Kerala-Einstein study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:197–9. 10.1111/jgs.12628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perrochon A, Kemoun G. The Walking Trail-Making Test is an early detection tool for mild cognitive impairment. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9:111 10.2147/CIA.S53645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Montero-Odasso M, Casas A, Hansen KT, et al. Quantitative gait analysis under dual-task in older people with mild cognitive impairment: a reliability study. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2009;6:35 10.1186/1743-0003-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steenland K, Karnes C, Seals R, et al. Late-life depression as a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease in 30 US Alzheimer’s disease centers. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;31:265–75. 10.3233/JAD-2012-111922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2508–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa022252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xu G, Liu X, Yin Q, et al. Alcohol consumption and transition of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;63:43–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ngandu T. Lifestyle-related risk factors in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study: Inst för neurobiologi. vårdvetenskap och samhälle/Dept of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sciences IIfP. India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: International Institute for Population Sciences, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mathuranath PS, Cherian PJ, Mathew R, et al. Dementia in Kerala, South India: prevalence and influence of age, education and gender. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:290–7. 10.1002/gps.2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mathuranath PS, Cherian JP, Mathew R, et al. Mini mental state examination and the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination: effect of education and norms for a multicultural population. Neurol India 2007;55:106 10.4103/0028-3886.32779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.