Abstract

Objective

To assess whether decentralising colposcopy services to a primary care facility in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa raises access to colposcopy.

Design

Before–after study comparing 2 years before and 2 years after decentralisation, using clinical records and laboratory data on cervical cytology and histology.

Primary outcome

The proportion of all women attending Hillbrow Community Health Centre (HCHC) with an abnormal Papanikolaou (Pap) smear who had a colposcopy post-decentralisation.

Setting

Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) has provided colposcopy services for several decades. HCHC, located about 3 km away, began colposcopy services in 2014.

Participants

Women, aged above 18 years, who had a colposcopy for diagnosis and treatment of precancerous cervical lesions following a Pap smear, from 2012 to 2016 at CMJAH or HCHC.

Results

Pre-decentralisation at CMJAH, 910 women had colposcopy (2012–2014). Post-decentralisation (2014–2016), 721 had colposcopy at CMJAH and 399 at HCHC, the decentralised facility. The number who had a Pap smear at HCHC and then a colposcopy rose threefold post-decentralisation (114 vs 350). Post-decentralisation, 43 women at HCHC were referred to CMJAH for colposcopy, compared with 114 pre-decentralisation. Post-decentralisation, 47.3% of women at CMJAH waited >6 months for colposcopy, while 35.5% did at HCHC (p<0.001). Across all three groups, 26.9%–30.3% of women had cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III lesions or carcinoma on colposcopy. The proportion of invalid specimens was similar at CMJAH and HCHC (1.8%–2.8%). Of 401 women who had an abnormal Pap smear at HCHC post-decentralisation, 267 had colposcopy (66.6%).

Conclusion

Decentralisation can decrease the time to colposcopy and reduce the workload of tertiary hospitals. Overall, more women accessed services. Colposcopy coverage at HCHC is higher than other sites, but could be further improved. Decentralisation did not appear to undermine the quality of services and this model could be extended to similar settings in South Africa and elsewhere.

Keywords: South Africa, colposcopy, cervical cancer, primary health care, decentralisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study included a relatively large number of women from high-volume facilities in all study groups, allowing us to detect differences between the time periods.

As the study assessed only one primary care centre in the first 2 years after decentralisation, we were unable ascertain the intervention’s long-term sustainability, or to assess the impact of a broader decentralisation strategy, such as a hub and spoke approach encompassing several primary care centres.

A hub and spoke approach has been successfully applied to other similar health services that require an integrated, tiered healthcare and laboratory system (such as Tuberculosis (TB) care and colorectal cancer screening), supporting the generalisability of the study findings to similar settings and assertions about the validity of the results reported.

The limited number of variables collected meant that the study could not investigate several important questions in detail, such as reasons for delays in colposcopy, the quality of decentralised services or comparisons of changes in access among women at the primary care site over time.

Data were collected for the purposes of patient care, and not specifically for research, potentially reducing data quality.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a largely preventable disease and WHO has recently launched an initiative aimed at eliminating the condition.1 At present, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women aged 15–44 years in the world.2 In South Africa, it is the most common cancer in that age group, and mortality rates are high.3 4 About 3% of women in South Africa harbour cervical human papilloma virus (HPV)-16/18, which is responsible for the majority of cases of cervical cancer in the country.4 Rates of cervical cancer in South Africa can partly be attributed to the high level of HIV.5 Women with HIV infection have a sevenfold higher rate of persistence of high-risk HPV compared with HIV uninfected women,6 heightening their risk for incident and progressive precancerous lesions. While antiretroviral therapy reduces the risk of cervical cancer and its precursors, the risk remains much higher than for HIV-negative women.7

In South Africa, the policy for cervical cancer screening was introduced in 2001 and updated in 2017.8 The policy recommends that low-risk women have three Papanikolaou (Pap) smears in a lifetime at the ages of 30, 40 and 50 years, while women with HIV infection are to be screened every 3 years, regardless of age. About 60% of women aged 30–49 years have had cervical cancer screening.9 Screening is predominately based on cytology using Pap smears, although there are plans to introduce liquid-based cytology which offers the potential to do HPV screening. Women with atypical findings on cytology are referred for colposcopy to establish a definitive diagnosis. During colposcopy, the view of the cervix is magnified and, where required, a biopsy is taken or a large loop excision of the transformation zone (Lletz) is conducted.10

The gap between screening for cervical cancer and treatment of high-risk lesions is believed to be very high in South Africa.11 Although there are few published data to support this assertion, the fact that the number of cervical cancer cases remains high despite the large number of cervical cancer screening procedures suggest this is the case. A range of health systems and patient factors influence access to colposcopy. System barriers include a limited number of colposcopy services, which are mostly centralised within tertiary-level facilities, with long waiting times for patients and few opportunities for non-specialist health workers to develop requisite skills.12 There are limited numbers of specialist gynaecologists within the public sector, and the high demands on these doctors for emergency and curative obstetric and gynaecology services may reduce their time available for diagnostic or preventive interventions, such as colposcopy. Another key factor is the complexity of providing Pap and other results to patients and then scheduling colposcopy appointments across the disjointed systems that often exist between a tertiary hospital and primary care centres.13–15 Patient-related factors linked with low uptake of colposcopy include low education levels, being single, fear of HIV testing and disclosure, a low CD4 count in HIV-infected women and transport costs for the additional visits.14 16 17 Patient demand for colposcopy is also undermined by a general fear of cancer, and lack of awareness or knowledge about cervical cancer.13 18 Poor patient–provider interactions restrict access, while a long-standing relationship with a primary clinician can optimise uptake.18

In South Africa, colposcopy procedures are generally done at tertiary-level facility, by specialist gynaecology oncologists and trainee gynaecologists under supervision. While there may be benefits to decentralising colposcopy services to lower levels of care, these need to be balanced by the advantages of centralisation of cancer services, such as concentrating clinical expertise, with a higher quality of care, and the rationalisation of expensive specialist equipment. Thus, in this before and after study, we aimed to determine if access to colposcopy increased following the decentralisation of colposcopy services from a tertiary-level hospital to a primary care facility in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. We compare the total number of colposcopies done and the coverage of colposcopy services in the primary-level facility after decentralisation. We also compare the two sites, specifically, the patient profile and cervical cancer risks, colposcopy procedures, quality of the services and histology outcomes.

Methods

Study participants and setting

Women, aged 18 years and older, who accessed colposcopy services at either Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) or Hillbrow Community Health Centre (HCHC) between October 2012 and September 2016 were included in the study. Both facilities are in subdistrict F of the Johannesburg Health District (JHD).

The colposcopy clinic at CMJAH is part of the Gynaecology-Oncology Department at CMJAH, which has two colposcopy machines. Women attending a facility in JHD who have an abnormal Pap smear are referred to the facility, where they are provided with an appointment date for colposcopy.

HCHC is situated in the densely populated inner-city area of Hillbrow, about 3 km from CMJAH.19 HCHC provides primary-level care, including a 24-hour casualty and a midwife obstetrics unit. The facility is run predominantly by nursing staff, with support from non-specialist medical doctors.

Implementation of decentralised services

In 2013, a review of patient files at HCHC found that a large proportion of women attending the HIV clinic had high-risk lesions on Pap smear.20 Moreover, there were reports from patients and health workers at HCHC of prolonged waiting times for colposcopy services at CMJAH. The Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute thus set about establishing decentralised colposcopy services at HCHC. A private sector company donated a colposcopy machine. Two district medical officers were trained by specialist gynaecology oncologists at CMJAH to provide the service. CMJAH staff provided ongoing support and established referral processes between the two facilities. Monthly meetings were held between staff at the two facilities, where concerns and difficult cases could be discussed.

The services, which began in October 2014, were provided twice a week by the medical officers, with assistance from the nurse who takes Pap smears at the facility. Patients attending HCHC and some referred from surrounding clinics were given an appointment for colposcopy if they had an abnormal Pap smear result, defined as: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), atypical squamous cell and HSIL cannot be excluded or squamous cell carcinoma.21 A few patients with Pap smear results other than those defined as abnormal smears were also referred for colposcopy. Patients with complex lesions, such as abnormal cervical anatomy or a high suspicion of cancer on Pap smear, were referred to CMJAH, as were those with a failed colposcopy. Colposcopy procedures included colposcopic assessment only, or colposcopic assessment together with either a Lletz or biopsy. Histology specimens were processed at the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS).

Data sources and collection

For the purpose of this evaluation, women who accessed colposcopy services at CMJAH and HCHC were divided into three groups: (1) pre-decentralisation at CMJAH between October 2012 and September 2014, (2) post-decentralisation at CMJAH between October 2014 and September 2016 and (3) post-decentralisation at HCHC between October 2014 and September 2016.

At CMJAH, we extracted data from paper-based records at the colposcopy clinic, including on patients’ age, HIV status, antiretroviral treatment, date of Pap smear, Pap smear result, date of colposcopy, colposcopy procedure performed and histology results. Data were entered into a REDCap electronic database (REDcap V.4.14.5, Vanderbilt University).22 At HCHC, demographic and clinical data on women who accessed colposcopy services were entered into an MS Excel spreadsheet after each patient visit. Data were obtained from the NHLS on Pap smear cytology for women attending HCHC who had a Pap smear and for the whole of JHD.

Study variables and statistical analysis

Access to colposcopy was measured by the total number of colposcopies done across the two facilities and the colposcopy coverage at HCHC, the primary study outcome. Coverage was estimated by calculating the proportion of all women at HCHC with an abnormal Pap smear who had a colposcopy. Time to colposcopy was calculated as the number of months from date of Pap smear to colposcopy and was categorised as optimal (under 3 months), acceptable (3–6 months) and delayed (>6 months). We also examined changes in referral patterns of women who had an abnormal Pap smear at HCHC.

Patient characteristics were compared between the three groups, as well as level of integration of HIV services (provision of HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment).

We also compared the types of colposcopy procedures performed in the different periods and histology findings. Histology results were classified as normal (includes benign endocervical polyp, atrophic ectocervical mucosa, koilocytotosis and metaplasia), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) I, CIN II, CIN III, carcinoma, other (includes infections such as cervicitis, inflammation and dysplasia) and invalid specimens (includes absent results). Quality of services was evaluated using proxy markers, specifically the proportion of invalid specimens and number of unsuccessful colposcopy procedures. Differences between the three study groups were assessed using a chi-square test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. All data were analysed using STATA V.13.0.

Patient and public involvement

The study utilised data that had already been collected as part of routine patient care, and thus patients were not directly involved in the study. We did, however, attempt to contact patients who had abnormal lesions on histology and had not attended follow-up visits.

Results

Access to colposcopy and timeliness of services

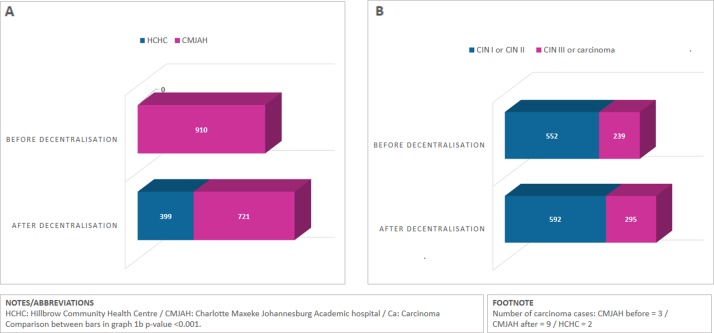

In total, 910 women accessed colposcopy at CMJAH between October 2012 and September 2014. In the subsequent 2 years, 1120 women had a colposcopy: 399 at HCHC (35.6%) and 721 at CMJAH (64.4%; table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and colposcopy outcomes at a community clinic (Hillbrow CHC), and a tertiary-level facility (CMJAH) before and after decentralisation

| Variables | Before versus after decentralisation at CMJAH | HCHC versus CMJAH after decentralisation | |||

| (A) Pre-decentralisation (2012–2014) n=910 |

(B) Post-decentralisation (2014–2016) n=721 |

P value (A vs B) |

(C) Hillbrow CHC (2014–2016) n=399 | P value (B vs C) |

|

| Characteristics | |||||

| Age groups in years | |||||

| <20 | 7 (0.8) | 6 (0.8) | |||

| 20–34 | 351 (39.8) | 209 (30.2) | 150 (37.6) | ||

| 35–44 | 342 (38.8) | 266 (38.4) | 156 (39.1) | ||

| 45–59 | 161 (18.3) | 187 (27.0) | 79 (19.8) | ||

| >60 | 20 (2.3) | 25 (3.6) | 0.001 | 7 (1.8) | 0.003 |

| HIV status known | 650 (71.4) | 429 (59.5) | <0.001 | 399 (100) | <0.001 |

| HIV status* | |||||

| Negative | 105 (16.2) | 59 (13.8) | 62 (15.5) | ||

| Positive | 545 (83.9) | 370 (86.3) | 0.28 | 337 (84.5) | 0.47 |

| On ART† | 428/544 (78.7) | 324/370 (87.6) | <0.001 | 336/337 (99.7) | <0.001 |

| Cervical cancer screening | |||||

| Facility where Pap smear done | |||||

| CMJAH | 115 (12.8) | 124 (17.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| HCHC | 114 (12.7) | 43 (6.1) | 307 (76.9) | ||

| Other clinic or hospital | 671 (74.6) | 540 (76.4) | <0.001 | 92 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Pap smear results | |||||

| NILM | 6 (0.7) | 8 (1.1) | 17 (4.3) | ||

| LSIL | 141 (15.5) | 125 (17.4) | 79 (20.0) | ||

| ASCUS | 19 (2.1) | 34 (4.7) | 4 (1.0) | ||

| HSIL | 678 (74.7) | 478 (66.4) | 263 (66.4) | ||

| ASC-H | 63 (6.9) | 65 (9.0) | 27 (6.8) | ||

| Carcinoma | 1 (0.1) | 10 (1.4) | <0.001 | 6 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Pap smear risk categories | |||||

| NILM, LSIL or ACSUS | 166 (18.3) | 167 (23.2) | 100 (25.3) | ||

| HSIL, ASC-H or carcinoma | 742 (81.7) | 553 (76.8) | 0.015 | 296 (74.8) | 0.44 |

| Cervical cancer diagnosis | |||||

| Procedure during colposcopy | |||||

| Visual inspection only | 37 (4.1) | 37 (5.2) | 63 (15.9) | ||

| Lletz | 337 (37.2) | 258 (35.9) | 231 (58.2) | ||

| Biopsy | 526 (58.0) | 420 (58.4) | 90 (22.7) | ||

| Other | 7 (0.8) | 4 (0.6) | 0.69 | 13 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Histology result‡ | |||||

| Normal | 27 (3.1) | 30 (4.4) | 45 (13.8) | ||

| CIN I | 254 (29.3) | 200 (29.3) | 84 (25.7) | ||

| CIN II | 298 (34.3) | 209 (30.7) | 99 (30.3) | ||

| CIN III | 236 (27.2) | 198 (29.0) | 86 (26.3) | ||

| Carcinoma | 3 (0.4) | 9 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Other§ | 34 (3.9) | 19 (2.8) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Invalid specimen | 16 (1.8) | 17 (2.5) | 0.10 | 9 (2.8) | <0.001 |

χ2 test for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

*Of those with a known HIV status.

†Of those HIV positive.

‡Of those with a histology specimen taken at biopsy, Lletz or other procedure.

§Other includes infections such as cervicitis, inflammation and dysplasia.

ASC-H, atypical squamous cell and HSIL cannot be excluded; ASCUS, Atypical squamous cell of uncertain significance; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CMJAH, Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital; HCHC, Hillbrow Community Health Centre; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; NILM, Negative for intraepithelial lesion and malignancy; Pap, Papanikolaou.

Figure 1.

(A) Total number of colposcopies done before and after decentralisation. (B) Number of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions detected before and after decentralisation. CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Of all Pap smears done in the JHD in the 2 years after decentralisation (114 983), 1.9% were done at HCHC (2227; table 2). Overall, 18.0% of Pap smears done at HCHC had abnormal cytology and required colposcopy (n=401), compared with only 8.2% of other women in JHD as a whole (n=1826; p<0.001). The estimated colposcopy coverage among women who had an abnormal Pap smear at HCHC was 66.6% (267/401; 95% CI 61.7% to 71.2%). The number of women who had a Pap smear at HCHC and then a colposcopy at either facility was threefold higher post-decentralisation than pre-decentralisation (from 113 to 350) (table 1).

Table 2.

Cytology results in the City of Johannesburg in 2014–2016

| Variable n (%) | Johannesburg health district* (n=114 983) | Hillbrow Community Health Centre (n=2227) | P value |

| Pap smear results | |||

| NILM | 74 969 (65.2) | 852 (38.3) | |

| LSIL | 23 212 (20.2) | 790 (35.5) | |

| ASCUS | 7391 (6.4) | 184 (8.3) | |

| HSIL | 7808 (6.8) | 364 (16.3) | |

| ASC-H | 1221 (1.1) | 28 (1.3) | |

| Carcinoma | 382 (0.3) | 9 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Number requiring colposcopy | |||

| No (NILM, LSIL or ASCUS) | 105 572 (91.8) | 9411 (82.0) | |

| Yes (HSIL, ASC-H or carcinoma) | 1826 (8.2) | 401 (18.0) | <0.001 |

Data from the National Health Laboratory Service. Excludes invalid or missing specimens, and other Pap smear results (n=2446).

*District total excludes HCHC.

ASC-H, atypical squamous cell and HSIL cannot be excluded; ASCUS, Atypical squamous cell of uncertain significance; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; NILM, Negative for intraepithelial lesion and malignancy; Pap, Papanikolaou.

Almost half of the women at CMJAH had a delay in receiving colposcopy (>6 months between Pap smear and colposcopy) post-decentralisation, compared with about a third pre-decentralisation (47.3% vs 36.2%, p<0.001; figure 1A). At HCHC, 21.7% of women had a colposcopy within 3 months of a Pap smear being taken (vs 11.8% at CMJAH pre- and 15.4% post-decentralisation, p<0.001).

The absolute number of women at CMJAH who had had a Pap smear at HCHC decreased from 113 to 43 in the second period. One-quarter of women who had a colposcopy at HCHC had had their Pap smear at another facility.

Characteristics of women in the three groups and HIV service integration

The proportion of women older than 45 years pre-decentralisation at CMJAH was 20.6%, post-decentralisation at CMJAH 30.6% and at HCHC 21.9% (p<0.001). At CMJAH, more women had a known HIV status pre-decentralisation than post-decentralisation (71.4% vs 59.5%, p<0.001). All women at HCHC had a documented HIV status. Around 85% of women with a known HIV status were HIV positive in all three groups. The proportion of positive women receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) rose in the second period at CMJAH from 78.7% to 87.6% (p<0.001), and almost all positive women were on ART at HCHC (99.7%; p<0.001) (table 1).

Description of colposcopy procedures, histology findings and colposcopy quality

At CMJAH, in both periods, ~60% of women had a biopsy at colposcopy (58.2%), while the same proportion had a Lletz at HCHC (58.2%). Three women who had a colposcopy at HCHC were referred to CMJAH due to an unsuccessful procedure.

Women at HCHC were 3.5-fold more likely to have a normal result on histology than women at CMJAH (95% CI:2.1–5.7). Post-decentralisation, 29.0% of women at CMJAH and 26.3% at HCHC had CIN III lesions (p=0.37; figure 1B). Post-decentralisation, 11 women had a diagnosis of carcinoma on histology (1.1%), compared with 3 before decentralisation (0.4%; p=0.06). The proportion of invalid specimens was similar across the three groups, ranging from 1.8% to 2.8% (table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we determined whether decentralisation to primary care level improved access to colposcopy services by reviewing the number of women attending the service before and after decentralisation, and the coverage of colposcopy among women at HCHC. We found that the cumulative number of colposcopies across the two facilities rose following decentralisation, and after only 2 years, HCHC was responsible for a third of all colposcopies in the subdistrict, even though it performs a negligible number of Pap smears relative to other sites. Overall, following decentralisation, threefold more women who had a Pap smear at HCHC had a colposcopy, and equally, at CMJAH, the proportion of women referred from HCHC reduced almost threefold. The marked increase in number of women from HCHC who had a colposcopy indicates that prior to decentralisation there may have been a large unmet need for the service, which was now being addressed, at least in part. The coverage reached 66.6%, considerably higher than figures in other settings.

Decentralisation of colposcopy services to primary-level care has several potential benefits. First, with adequate training, tasks that had been performed by highly specialised staff can be shifted to lower health worker cadres, allowing specialists to focus on more complex cases.23 Additionally, decentralisation may alleviate patient barriers to access, by bringing services closer to them—in settings they are familiar with—and reducing their transport and other costs.13 23 Decentralisation has long been central to the provision of HIV services in this setting through, for example, task shifting, providing antiretroviral treatment in primary care services and the dispensing of drugs from local pharmacies, rather than clinics.24

Decentralisation of colposcopy can take several forms, including telecolposcopy from distant sites, outreach portable colposcopy, shifting of services to nurse practitioners or medical officers and decentralisation to lower-level facilities, as in this study.25 In other settings, shifting services to lower care levels was found to be cost-effective, acceptable to patients and to increase rates of attendance for colposcopy.16 25 26 In the Western Cape, South Africa, for example, colposcopy services were decentralised to a district hospital and provided by a gynaecologist.23 This raised uptake of the service and reduced time to procedure. In high-income countries, services have been successfully decentralised to community health centres and portable outreach programmes in Alaska, the USA, and parts of Canada and Australia, targeting immigrant, Inuit and other vulnerable women.16 17 26–28 The National Health Service in UK has gone a step further and colposcopy is often performed by nurse practitioners once they have completed certification procedures.29

Women attending HCHC colposcopy were at lower risk than those at CMJAH, as shown by their lower grades of abnormalities on Pap smear and histology. Women at HCHC were also younger than those at CMJAH, important as risk for cervical cancer is higher in rises considerably with age (the mean age at diagnosis of cervical cancer is 52.3 in South Africa).30 These findings may suggest that, as the programme had envisaged, higher-risk patients are being referred to CMJAH. Overall, services at HCHC appear to be performing well, with all women tested for HIV and almost all those positive were receiving ART. In addition, colposcopy services were now integrated into their care, which was previously off-site, complex to access and marked by lengthy delays. HIV-positive women made up the large majority of patients in all groups, reflecting the higher levels of risk for cervical cancer in this population. Clearly, it remains a priority to integrate screening for cervical cancer within all clinics providing antiretroviral treatment. Equally, ART and services such as screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections could be integrated within colposcopy clinics, reducing the opportunity costs associated with multiple visits to the clinic and lowering the risk of loss to follow-up.

The similar number of invalid histology samples and the isolated cases of failed colposcopy suggests that the quality of colposcopy services at HCHC may have been comparable to CMJAH. Unlike at CMJAH, however, Lletz was the most common procedure at HCHC, in keeping with evidence that Lletz is better suited to lower-level facilities and staff.10 With decentralisation, it is critical to ensure that staff are adequately trained and service quality is closely monitored. The hesitancy to decentralise colposcopy to date, may reflect underlying concerns that cases of cancer may go undetected by lower-level staff. In some settings, lower-level health workers undergo a process of certification and have to perform a certain number of colposcopies per year to remain registered.29 While this approach may hold advantages, onerous processes around certification and recertification may lead to staff discontinuing colposcopy.31

The decline in number of colposcopies at CMJAH is concerning, and may reflect factors other than a reduction in demand that accompanies decentralisation. Fewer women at the site had a known HIV status and waiting times for colposcopy lengthened. Thus, though decentralisation can reduce the patient burden at referral centres, this does not necessarily translate into improved services at that site. Other factors may play a larger influence, for example, coinciding with the period after decentralisation, CMJAH lost a number of senior specialists.

Delays in colposcopy vary considerably between settings, from an average of 39 days from referral to colposcopy in one study in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa,12 to around 5–6 months in both our study and another in the Western Cape.23 It is concerning that time from Pap smear to colposcopy is >6 months for half the women at CMJAH, and a third at HCHC. Reducing these delays is clearly a priority at both sites. We were unable, however, to discern reasons for these delays, which could be caused by delays in providing the results of Pap smears to patients, patient delays in making or attending appointments, or shortages of specialist staff. We could also not investigate which group of patients required referral to higher levels of care, and future studies might attempt to define criteria for referral. Moreover, given the relatively short period of the review, we are unable to assess sustainability of the services in the long-run, a pressing question. Lastly, the study evaluated the use of colposcopy following cytological screening with Pap smears and these findings may not be generalisable to screening with HPV testing.29 HPV testing has a considerably higher sensitivity for detecting precursor lesions of cervical cancer compared with cytology, and thus may alter the number of patients requiring colposcopy and types of lesions identified.32 33

Conclusion

In conclusion, decentralisation of colposcopy services can improve access to colposcopy, resulting in faster diagnoses of precancerous lesions of the cervix, more lesions being treated with Lletz and a reduction in the burden of patients in tertiary hospitals. Most importantly, increasing the number of colposcopies and treatments of precancerous lesions could reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. This is particularly important among HIV-positive women who now live longer with ART, and the treatment of their co-morbidities is rapidly gaining in importance. Though coverage of colposcopy reached two-thirds at HCHC, it is important to identify interventions to further raise coverage levels. Decentralisation is unlikely to affect the quality of services if medical officers are appropriately trained, supervised and supported by clear referral guidelines. The approach presented here could be extended to other similar primary-level or secondary-level facilities in South Africa, and perhaps encompass the use of portable colposcopes or telecolposcopy, under close supervision. If done correctly and at scale, decentralisation of colposcopy services, could shore up cervical cancer prevention and finally decrease the public health burden and mortality due to the cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following persons who contributed to this study:

H. Manyonga, Z. Dumakude, A. Moholola, N. Wattrus, L. Mbuyisa, I. Sishi, N. Twala, S. Sidabuka, E. Briedenhann, L. Mavuya, K. Moshaba, S. Mzobe, S. Carmona (NHLS), L. Chauke (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, CMJAH).

Footnotes

Contributors: Category 1. Conception and design of study: GM, XN, SS, NM and MC. Acquisition of data: GM, XN and NM. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: GM, XN, SS, EK, MC, HR and TS. Category 2. Drafting the manuscript: GM, XN, NM, SS, EK and MC. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: MC, HR and TS. Category 3. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published: GM, XN, NM, SS, TS, HR, EK and MC.

Funding: This study has been made possible through funding from USAID-PEPFAR, grant number: AID-A-12-67400021. We would also like to acknowledge the following organisations for donating a colposcopy machine to Hillbrow CHC: Vodacom, Altech and Altron.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand (Certificate number: M151184). Permission for use of the CMJAH data was granted by the hospital’s Chief Executive Officer, and the head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at CMJAH. The NHLS Academic Affairs and Research Office gave permission for use of their data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional unpublished data from the study.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. WHO. Cervical cancer: an ncd we can overcome: call to action. 2018. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/DG_Call-to-Action.pdf

- 2. Bruni L, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Albero G, et al. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). human papillomavirus and related diseases in the world. Summary report 27 July 2017. http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf.

- 3. Batra P, Kuhn L, Denny L. Utilisation and outcomes of cervical cancer prevention services among HIV-infected women in Cape Town. S Afr Med J 2010;100:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. South Africa human papillomavirus and related cancers, fact sheet 2017. 2017. http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/ZAF_FS.pdf

- 5. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adler D, Wallace M, Bennie T, et al. High risk human papillomavirus persistence among HIV-infected young women in South Africa. Int J Infect Dis 2015;33:219–21. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guiguet M, Boué F, Cadranel J, et al. Effect of immunodeficiency, HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy on the risk of individual malignancies (FHDH-ANRS CO4): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1152–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Department of Health South Africa. Cervical cancer prevention and control policy. 2017.

- 9. Day C, Gray A, Ndlovu N. South African health review 2018. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO. WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94830/9789241548694_eng.pdf;jsessionid=F65ED4960A15E4D16BB15F6E57F71518?sequence=1; [PubMed]

- 11. Denny L, Kuhn L. Cervical cancer prevention and early detection from a South African perspective. Chapter 18: South African Health Review Published by Health Systems Trust, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katz IT, Butler LM, Crankshaw TL, et al. Cervical abnormalities in South African women living with hiv with high screening and referral rates. J Glob Oncol 2016;2:375–80. 10.1200/JGO.2015.002469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dawood S. Barriers and facilitators to colposcopy attendance. Following an abnormal pap smear: patient and provider perspectives. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Momberg M, Botha MH, Van der Merwe FH, et al. Women’s experiences with cervical cancer screening in a colposcopy referral clinic in Cape Town, South Africa: a qualitative analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013914 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoque M, Hoque E, Kader SB. Evaluation of cervical cancer screening program at a rural community of South Africa. East Afr J Public Health 2008;5:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin B, Smith W, Orr P, et al. Investigation and management of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Canadian Inuit: enhancing access to care. Arctic Med Res 1995;54(Suppl 1):117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Payne S, Jarrett N, Jeffs D. The impact of travel on cancer patients' experiences of treatment: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care 2000;9:197–203. 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baranoski AS, Stier EA. Factors associated with time to colposcopy after abnormal Pap testing in HIV-infected women. J Womens Health 2012;21:418–24. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rees H, Delany-Moretlwe S, Scorgie F, et al. At the heart of the problem: health in Johannesburg’s inner-city. BMC Public Health 2017;17(Suppl 3):554 10.1186/s12889-017-4344-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stadler J, Chikandiwe A, Mayaud P, et al. Biographies of HIV and Cervical Cancer: Understanding Treatment-Seeking Amongst HIV Positive Women in Inner City Johannesburg: IAS conference, Durba, South Africa, Oral presentation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Botha MH. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening in South Africa. Southern African Journal of Gynaecological Oncology 2017;9:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blanckenberg ND, Oettle CA, Conradie HH, et al. Impact of introduction of a colposcopy service in a rural South African sub-district on uptake of colposcopy. S Afr J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;19:81 10.7196/sajog.388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task- shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health 2010;8:8:8 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bishai DM, Ferris DG, Litaker MS. What is the least costly strategy to evaluate cervical abnormalities in rural women? Comparing telemedicine, local practitioners, and expert physicians. Med Decis Making 2003;23:463–70. 10.1177/0272989X03260136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogilvie GS, Shaw EA, Lusk SP, et al. Access to colposcopy services for high-risk Canadian women: can we do better? Can J Public Health 2004;95:346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gifford MS, Stone IK. Quality, access, and clinical issues in a nurse practitioner colposcopy outreach program. Nurse Pract 1993;18:25–36. 10.1097/00006205-199310000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hartz LE. Quality of care by nurse practitioners delivering colposcopy services. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 1995;7:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Public Health England, National Health Service. NHS cervical screening programme colposcopy and programme management. Third edition: NHSCSP Publication number 20, 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/515817/NHSCSP_colposcopy_management.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olorunfemi G, Ndlovu N, Masukume G, et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of cervical cancer in South Africa (1994-2012). Int J Cancer 2018;143:2238–49. 10.1002/ijc.31610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sonnex C. Providing a genitourinary medicine colposcopy service. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:8–10. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dijkstra MG, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, et al. Cervical cancer screening: on the way to a shift from cytology to full molecular screening. Ann Oncol 2014;25:927–35. 10.1093/annonc/mdt538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the performance of liquid-based cytology: insights from the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer 2014;134:1835–43. 10.1002/ijc.28514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.