Abstract

Objectives

The total medical (economic) costs of haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD), including direct medical costs, out-of-pocket (OOP) costs and productivity losses, have become an important issue. This study aims to compare the direct non-medical costs and indirect medical costs of both modalities in Taiwan.

Design and setting

This multicentre study included cross-sectional interviews of patients over 20 years old and articulate, who had been continuously receiving long-term HD or PD for more than 3 months between April 2015 and March 2016. Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test and 1000 bootstrap procedures with replacement were used for analysis.

Outcome measures

Differences in OOP costs and productivity losses.

Results

There were 308 HD and 246 PD patients available for analysis. HD patients had significantly higher monthly OOP costs than PD patients after bootstrap procedures (NTD 5912 vs NTD 5225, p<0.001; NTD, new Taiwan dollars; 1 US dollar=30 NTD). Compared with PD patients, HD patients had higher monthly productivity losses after bootstrap procedures (NTD 14 150 vs NTD 11 611, p<0.001), resulting from more time spent seeking outpatient care (HD, 70.4 hours vs PD, 4.4 hours, p<0.001) and time spent by family caregivers for outpatient care (HD, 66.1 hours vs PD, 6.1 hours, p<0.001). The total costs per patient–month of HD and PD modalities, including OOP costs and productivity losses, were NTD 20 062 and NTD 16 836, respectively.

Conclusions

The HD modality has higher OOP costs and productivity losses than the PD modality in Taiwan.

Keywords: cost, haemodialysis, out-of-pocket cost, peritoneal dialysis, productivity loss

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This multicentre study included cross-sectional interviews of long-term haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients.

Previous study seldom assessed the information about out-of-pocket (OOP) payments and productivity losses collected from a patient undergoing HD and PD.

The difference in the proportion of age groups in HD and PD patients is the major drawback of this study.

The sample size could not represent the general population of HD and PD patients in Taiwan because the sampled patients were also not randomised.

The 12-month recall period of healthcare utilisation in this study could make sure all OOP information in the previous year captured in the answer but possibly caused a recall bias.

Introduction

Since March 1995, when Taiwan began implementing the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, the per capita healthcare expenditure has increased annually, especially in the care of ‘end-stage renal disease’ (ESRD) patients. Taiwan has the highest incidence and prevalence rates of ESRD in the world.1–3 By 2017, the cost of dialysis (new Taiwan dollars, NTD, 36.9 billion; 1 US dollar=30 NTD in December 2017) accounted for a staggering 5.73% of the total annual NHI expenditure (NTD 644.1 billion).3 Haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) are the two major renal replacement modalities in Taiwan with a similar all-cause mortality rate.4–7 Several studies have provided clear evidence that HD has higher direct medical costs among the two modalities.8–14 NHI administrators implemented several strategies besides applying a blanket budget cap on dialysis expenditure to contain the total costs of dialysis and incentivize the use of PD modality. These efforts included increasing the reimbursements for PD and extending the NHI payment scheme covering the automated PD machine costs. As the proportion of PD usage increases, its prevalence in Taiwan has been gradually increasing, from 6.5% in 2003 to 8.5% in 2007, and up to 9.2% in 2014, similar to the average level within the developed countries.15–18

ESRD prevalence is increasing with the rise in the number of ageing and diabetic nephropathy patients. The total (economic) costs of HD and PD modalities, including direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs and productivity losses, have become an important issue.19 Direct medical costs incurred for medical services, such as dialysis costs, physician and nurses’ services, diagnostic tests and hospitalisation costs, are the most common type cited in the literature. From a payer’s perspective (eg, national insurance organisations), these costs are the most important. However, from a patient’s as well as societal perspectives, out-of-pocket (OOP) costs and productivity losses are nominal and meaningful. OOP costs and productivity losses have not been assessed comprehensively in ESRD patients for two reasons: the methods for collecting these data for the ESRD patients are not well established, and retrospective data collection is difficult. Only two studies have reported that PD had less OOP costs and productivity losses than HD in Brazil and Singapore, but detailed data were not stated.12 20 These studies highlighted a significant economic burden due to dialysis and a higher direct healthcare costs associated with the use of HD modality; however, little information is available about OOP costs, including expenses on caregivers or transportation, as well as productivity losses, including job loss, worker replacement and reduced productivity from patients and family. According to the 2016 Annual Report on Kidney Disease in Taiwan, HD patients had higher NHI expenses (NTD 70 000 per patient–month) than PD patients (NTD 51 000 per patient–month), owing to higher cost of outpatient care (HD, NTD 56 000 per patient–month; PD, NTD 43 000 per patient–month) and inpatient care (HD, NTD 13 400 per patient–month; PD, NTD 8200 per patient–month).15 However, the extent to which OOP costs and productivity losses contribute to the overall economic burden of HD and PD are yet to be explored in Taiwan. We, therefore, conducted this study from a patient’s and societal perspectives, using face-to-face interviews to compare OOP costs and productivity losses between HD and PD patients in Taiwan.

Methods

Study design

Ours was a multicentre study using cross-sectional interviews with patients over 20 years old, carried out at the nephrology outpatient clinics of five hospitals and five dialysis clinics located in northern, central, southern and eastern Taiwan between April 2015 and March 2016. All aspects of the study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were asked for input in the creation of this article.

Sampling

Articulate ESRD patients who were receiving long-term HD or PD continuously for more than 3 months were chosen. Those aged less than 20 years or unable to communicate were excluded. Patients were recruited and enrolled using a 1:1 male-to-female enrolment design. A total of 581 ESRD patients were screened at the contributing sites, of whom 554 were eligible and enrolled. In total, there were 308 HD patients (156 men and 152 women) and 246 PD patients (124 men and 122 women; 117 automated PD and 129 continuous ambulatory PD) available for analysis.

The patient interviews were performed face by face by well-trained nurses from the site or graduate students from the Taipei Medical University during HD therapy or monthly PD clinic visit. All interviewers had attended prior interviewer training. The patients’ baseline characteristics were collected from their medical chart and own response. The patient details collected include sociodemographics, comorbidities, cause of ESRD and dialysis data (tables 1 and 2). We examine the differences in OOP costs and productivity losses between HD and PD patients. OOP costs included all expenses related to ESRD paid by the patients/family and not reimbursed by the NHI, such as expenses for medicines, medical materials and devices, herbal and alternative medicines, nutritional supplements, transportation costs and caregiver costs. By using the ‘human capital approach’,21 productivity losses were valued and measured by multiplying the loss of time in hours or days with average hourly/daily wage rate reported by the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Taiwan (see online supplementary table 1). There were two sources of time loss being evaluated: patients’ and caregivers’ time spent in seeking care and time spent in operating the dialysis apparatus at home.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the interview survey patients

| Variables | HD (n=308) | PD (n=246) | P value |

| Male gender | 156 (50.7) | 124 (50.4) | 0.96 |

| Age (years) | 61.0 (12.7) | 56.2 (13.9) | <0.01 |

| <50 | 68 (22.1) | 71 (28.9) | |

| 50–59 | 79 (25.7) | 67 (27.2) | |

| 60–69 | 76 (24.7) | 70 (28.5) | |

| ≥70 | 85 (27.6) | 38 (15.5) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 130 (42.2) | 74 (30.1) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 204 (66.2) | 193 (78.5) | <0.01 |

| Cancer | 17 (5.5) | 7 (2.9) | 0.13 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.81) | 0.40 |

| Cirrhosis of liver | 5 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) | 0.91 |

| Dementia | 3 (1.0) | 4 (1.6) | 0.50 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (2.6) | 6 (2.4) | 0.91 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 15 (4.9) | 8 (3.25) | 0.34 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 36 (11.7) | 20 (8.1) | 0.17 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 22 (7.1) | 6 (2.4) | 0.01 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 (3.6) | 8 (3.3) | 0.84 |

| Chronic heart failure | 13 (4.2) | 9 (3.7) | 0.74 |

| Cause of end-stage renal disease | |||

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 111 (36.0) | 82 (33.3) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 118 (38.3) | 71 (28.9) | 0.11 |

| Hypertension | 108 (35.1) | 52 (21.1) | 0.02 |

| Hereditary polycystic kidney disease | 10 (3.3) | 6 (2.4) | 0.83 |

| Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.9) | 0.19 |

| Lupus nephritis | 4 (1.3) | 11 (4.5) | <0.01 |

| Others | 51 (16.6) | 43 (17.5) | 0.21 |

| Marital status | 0.18 | ||

| Singled | 45 (14.6) | 52 (21.1) | |

| Married | 210 (68.2) | 159 (64.6) | |

| Divorced | 25 (8.1) | 15 (6.2) | |

| Widowed | 28 (9.1) | 20 (8.1) | |

| Education years | 0.09 | ||

| Below primary school | 26 (8.4) | 15 (6.1) | |

| Primary school | 77 (25.0) | 51 (20.7) | |

| Junior high school | 50 (16.2) | 31 (12.6) | |

| Senior high school | 88 (28.6) | 69 (28.1) | |

| College | 59 (19.2) | 66 (26.8) | |

| Above college | 8 (2.6) | 14 (5.7) | |

| Family income (NTD) | 0.17 | ||

| <30 000 | 93 (30.2) | 80 (32.5) | |

| 30 000–49 999 | 99 (32.1) | 61 (24.8) | |

| 50 000–69 999 | 61 (19.8) | 46 (18.7) | |

| 70 000–99 999 | 31 (10.1) | 25 (10.1) | |

| 100 000–149 999 | 9 (2.9) | 23 (9.4) | |

| 150 000–199 999 | 6 (2.0) | 8 (3.3) | |

| ≥200 000 | 9 (2.9) | 3 (1.2) | |

Data were number (%) or mean (SD).

HD, haemodialysis; NTD, new Taiwan dollars (1 US dollar=30 NTD); PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Table 2.

Dialysis-related baseline data of interview survey patients

| Variables | HD (n=308) | PD (n=246) | P value |

| Duration of dialysis (month) | 63 (26–135) | 37 (16–63) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 141.8 (24.7) | 141.0 (23.2) | 0.58 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 76.1 (12.6) | 82.3 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 77.5 (10.3) | 81.8 (15.1) | <0.01 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Standard Kt/V (HD) or Kt/V (PD) | 2.39 (0.32) | 1.97 (0.31) | <0.001 |

| Urea reduction ratio | 73.9 (6.2) | – | – |

| Weekly creatinine clearance (mL/min) | – | 60.1 (12.5) | – |

| Normalised protein nitrogen appearance | – | 1.0 (0.2) | – |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.5 (1.5) | 10.1 (1.5) | <0.01 |

| Body mass index | 23.7 (4.5) | 23.9 (3.9) | 0.22 |

Data were median (IQR) or mean (SD).

HD, haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

bmjopen-2018-023062supp001.pdf (139.9KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

The analyses began with a baseline comparison of patients receiving either HD or PD therapy. Frequencies for categorical variables and means with SD or medians with IQRs for continuous variables were calculated. Statistical differences between the HD and PD patients were determined with χ2 tests, Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate to analyse the patient interview survey data. Finally, as patient characteristics and costs may differ outside clinical settings and in different conditions, a bootstrap analysis was further performed on OOP costs and productivity losses, by applying 1000 bootstrap procedures of HD and PD patients with replacement, stratified by age groups. The difference between the groups was significant for the two-sided p value <0.05. All the analyses in this study were carried out using the SAS V.9.3 software.

Sensitivity analysis

Moreover, the HD and PD patients are a group of patients with a debilitating illness and may receive lower wage rates than the general population resulting in lower productivity losses. To assess the impact of productivity losses on the sum of OOP costs and productivity losses, we first defined the total costs of OOP costs and productivity losses after bootstrap analysis as Model 1. Then we adjusted the productivity losses for the mean Taiwan unemployment rate (3.82%) during the interview period (between April 2015 and March 2016) and then set the productivity losses with a 20%, 30% or 40% decrement of wages as different scenarios (Model 2–4) to calculate the total amount of these two costs.22

Results

A total of 308 HD patients and 246 PD patients were interviewed in the multicentre cross-sectional study. Patient baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. HD patients were older as more patients were over 70 years old. Diabetes and ischaemic heart disease prevalence were higher and hypertension was lower in HD patients. Hypertension and lupus nephritis had a discernibly different causation of ESRD between the HD and PD patients. Marital status, education and income were not statistically different between the groups. The dialysis-related baseline data are reported in table 2, where the maximum differences were found to be the duration of dialysis, haemoglobin, serum albumin and potassium.

Table 3 shows the results of the per patient–month OOP costs. There were discernible differences between the HD and PD patients in the OOP costs (NTD 5922 vs NTD 5237, p<0.01). The HD patients had significantly lower copayment for outpatient visits, medicine not covered by NHI and medical equipment, but higher copayment for hospitalizations and transportation than the PD patients. Chinese medication, traditional medicine and nutritional supplements showed no discernible differences between groups. Another main source of the differences between the HD and PD patients were the transportation costs, owing to more frequent transportation in the former group. However, the results of the mean OOP costs were not consistent in each age group. PD patients had significantly higher OOP costs than the corresponding HD patients in the age groups of 50–59 years old and over 70 years old.

Table 3.

Per patient–month out-of-pocket costs of the interview survey patients (in NTD)

| Variables | HD (n=308) | PD (n=246) | P value | ||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Before bootstrap procedures | |||||

| Total | 5922 (12 963) | 1794 (488 –4784) | 5237 (7571) | 2492 (1018–5598) | <0.01 |

| Copayment to outpatient care | 103 (377) | 0 (0–120) | 361 (696) | 120 (50–400) | <0.001 |

| Copayment to inpatient care | 2209 (11 093) | 0 (0–0) | 995 (2163) | 0 (0–1240) | <0.001 |

| Medicine not covered by NHI | 591 (1832) | 0 (0–417) | 995 (1911) | 125 (0–1078) | <0.001 |

| Medical equipment | 110 (448) | 0 (0–0) | 439 (726) | 208 (0–675) | <0.001 |

| Chinese medication | 27 (175) | 0 (0–0) | 183 (2153) | 0 (0–0) | 0.53 |

| Traditional medicine | 38 (257) | 0 (0–0) | 51 (550) | 0 (0–0) | 0.35 |

| Nutritional supplements | 241 (749) | 0 (0–0) | 542 (2398) | 0 (0–106) | 0.26 |

| Transportation costs | 1028 (1707) | 293 (0–1495) | 191 (229) | 143 (16–293) | <0.001 |

| Caregiver costs | 1574 (5453) | 0 (0–0) | 1480 (5309) | 0 (0–0) | 0.90 |

| Stratified by age groups | |||||

| Age <50 (years) | 3766 (5785) | 2771 (3150) | 0.32 | ||

| Age 50–59 (years) | 4902 (14 857) | 5824 (7484) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 60–69 (years) | 7337 (14 140) | 4091 (6072) | 0.68 | ||

| Age ≥70 (years) | 7330 (13 980) | 10 922 (12 006) | <0.01 | ||

| After bootstrap procedures | |||||

| Total | 5912 (819) | 5225 (485) | <0.001 | ||

| Stratified by age groups | |||||

| Age <50 (years) | 3787 (686) | 2776 (375) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 50–59 (years) | 4814 (1678) | 5827 (870) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 60–69 (years) | 7270 (1559) | 4111 (701) | <0.001 | ||

| Age ≥70 (years) | 7348 (1521) | 10 932 (1855) | <0.001 | ||

HD, haemodialysis; NHI, National Health Insurance; NTD, new Taiwan dollars (1 US dollar=30 NTD); PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Results of the per patient–month productivity losses are reported in table 4. Compared with the PD patients, the HD patients had higher monthly productivity losses (NTD 14 147 vs NTD 11 604, p<0.01), resulting from more time spent seeking outpatient care (HD, 70.4±6.9 hours vs PD, 4.4±2.5 hours, p<0.001) and time spent by family caregivers for outpatient care (HD, 66.1±51.5 hours vs PD, 6.1±4.1 hours, p<0.001). However, only 10.4% and 31.3% of HD and PD patients, respectively, had family caregivers who accompanied them for outpatient care. The productivity losses resulting from time spent operating the dialysis apparatus (49.9±27.8 hours) were only seen in PD patients but not in HD patients. After the 1000 bootstrap procedures, the results of the mean productivity losses remained unchanged in each age group. HD patients had significantly lower productivity losses in the age group over 70 years old because no productivity losses were included beyond the age of 70 years.

Table 4.

Per patient–month productivity losses of the interview survey patients (in NTD)

| Variables | HD (n=308) | PD (n=246) | P value | ||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Before bootstrap procedures | |||||

| Total | 14 147 (10 746) | 13 936 (6961–20 921) | 11 604 (7949) | 10 576 (5315–16 764) | <0.01 |

| Time spent operating dialysis apparatus | – | – | 8655 (6785) | 7450 (3138–12 700) | |

| Seeking outpatient care from patients | 11 307 (8007) | 12 874 (0–17 567) | 774 (591) | 798 (399 –1008) | <0.001 |

| Seeking outpatient care from caregivers | 1608 (5793) | 0 (0–0) | 400 (759) | 0 (0–833) | <0.001 |

| Seeking inpatient care from patients | 799 (1683) | 0 (0–0) | 1037 (1482) | 0 (0–2918) | 0.01 |

| Seeking inpatient care from caregivers | 433 (1251) | 0 (0–0) | 739 (1290) | 0 (0–733) | <0.001 |

| Stratified by age groups | |||||

| Age <50 (years) | 19 419 (5888) | 13 177 (7000) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 50–59 (years) | 19 276 (10 606) | 14 424 (7579) | <0.01 | ||

| Age 60–69 (years) | 17 253 (7901) | 12 826 (6789) | <0.001 | ||

| Age ≥70 (years) | 2386 (6184) | 1207 (1621) | <0.01 | ||

| After bootstrap procedures | |||||

| Total | 14 150 (626) | 11 611 (510) | <0.001 | ||

| Stratified by age groups | |||||

| Age <50 (years) | 19 381 (715) | 13 289 (840) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 50–59 (years) | 19 272 (1162) | 14 415 (878) | <0.001 | ||

| Age 60–69 (years) | 17 212 (857) | 12 823 (802) | <0.001 | ||

| Age ≥70 (years) | 2403 (645) | 1206 (255) | <0.001 | ||

HD, haemodialysis; NTD, new Taiwan dollars (1 US dollar=30 NTD); PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Table 5 reports the total costs per patient–month, including OOP costs and productivity losses. The productivity losses were further adjusted for mean Taiwan unemployment rate (3.82%) during the interview survey periods. Models 2–4 show the total costs including OOP costs and productivity losses adjusted for unemployment rate with a 20%, 30% or 40% decrement of wages as different scenarios. After considering the productivity losses under various scenarios, the differences in total costs between the HD and PD patients slightly decreased in Models 2–4. After stratified by age groups, the total costs per patient–month of HD patients were higher than those of PD patients except in the age group older than 70 years old.

Table 5.

Total costs of out-of-pocket costs and productivity losses per patient–month of HD and PD patients after bootstrap analysis (in NTD)

| Variables | HD | PD | Difference |

| (1) Out-of-pocket costs | 5912 | 5225 | 687 |

| Stratified by age groups | |||

| Age <50 (years) | 3787 | 2776 | 1011 |

| Age 50–59 (years) | 4814 | 5827 | −1013 |

| Age 60–69 (years) | 7270 | 4111 | 3159 |

| Age ≥70 (years) | 7348 | 10 932 | −3584 |

| (2) Productivity losses | 14 150 | 11 611 | 2540 |

| Stratified by age groups | |||

| Age <50 (years) | 19 381 | 13 289 | 6093 |

| Age 50–59 (years) | 19 272 | 14 415 | 4858 |

| Age 60–69 (years) | 17 213 | 12 823 | 4390 |

| Age ≥70 (years) | 2403 | 1206 | 1197 |

| (3) Total costs | |||

| Model 1=(1) + (2) | 20 062 | 16 836 | 3227 |

| Stratified by age groups | |||

| Age <50 (years) | 23 168 | 16 065 | 7103 |

| Age 50–59 (years) | 24 086 | 20 242 | 3844 |

| Age 60–69 (years) | 24 483 | 16 934 | 7549 |

| Age ≥70 (years) | 9751 | 12 138 | −2387 |

| Model 2=(1)+(2)×20% decrement in wages×(1–0.0382)* | 16 800 | 14 159 | 2641 |

| Model 3=(1)+(2)×30% decrement in wages×(1–0.0382)* | 15 439 | 13 042 | 2397 |

| Model 4=(1)+(2)×40% decrement in wages×(1–0.0382)* | 14 078 | 11 925 | 2153 |

*Adjusted for mean Taiwan unemployment rate (3.82%) between April 2015 and March 2016.

HD, haemodialysis; NHI, National Health Insurance; NTD, new Taiwan dollars (1 US dollar=30 NTD); PD, peritoneal dialysis.

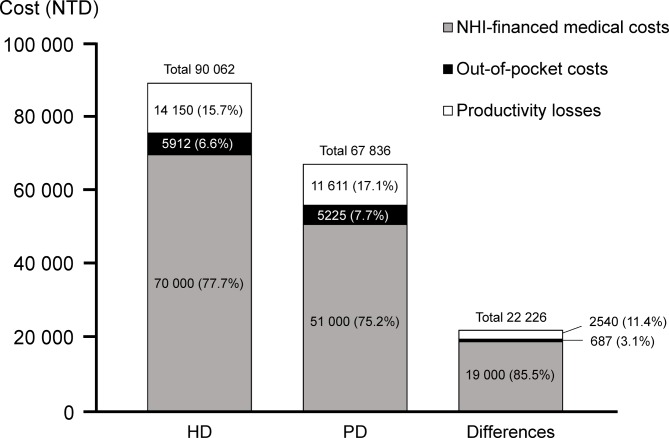

Incorporating the NHI-financed medical costs of HD and PD reported in the 2016 Annual Report on Kidney Disease in Taiwan into the findings in this study,15 figure 1 shows the per patient–month total costs are NTD 90 062 for HD and NTD 67 836 for PD, to which OOP costs contributed 6.6% and 7.7%, and productivity losses 15.7% and 17.1%, respectively. For the NTD 22 227 per patient–month difference in the costs of HD and PD, OOP and productivity losses account for 3.1% and 11.4% of the differences, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of NHI-financed medical cost,15 out-of-pocket costs and productivity losses, in HD and PD modalities, and their differences. HD, haemodialysis; NHI, National Health Insurance; NTD, new Taiwan dollars (1 US dollar=30 NTD); PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Discussion

The main results of this cross-sectional, multicentre interview survey demonstrate that total monthly OOP costs and productivity losses of HD (NTD 19 522) were higher than that of PD (NTD 16 392) after adjusting for unemployment rate. The OOP costs for the HD patients were NTD 687 higher than that for the PD patients, with the greatest difference being found in the costs of copayment to hospitalizations and transportation costs. The main sources of the differences between HD and PD patients for productivity losses were seeking outpatient care and time spent operating the dialysis apparatus. The total economic costs of HD (NTD 90 062), including NHI expenses, OPP costs and productivity losses, were higher than those of PD (NTD 67 836), which were mostly contributed by NHI expenses (NTD 19 000, 85.5%) (figure 1).

These findings are rarely assessed in previous studies but important for the care of ESRD patients because the OOP costs and productivity losses constitute an important, but frequently omitted, part of the overall evaluation of economic burden borne by patients and their families. Previous studies reported that a significantly higher total NHI-financed medical costs were discernible among the HD patients than among the PD patients in several countries, including Taiwan, the USA and the UK.10 15 23 The total costs per patient–month of HD and PD patients, including the OOP costs and productivity losses (table 5, Model 1), were NTD 20 063 and NTD 16 836, respectively, with a difference of NTD 3227 per patient–month. From the payer’s perspective, the NHI-financed medical costs of PD seems to be a better cost-saving modality; similarly, from a patient’s and societal perspective, the total costs per patient–month of HD were higher owing to higher OOP costs except in the age group more than 70 years old (table 5). Aged ESRD patients often have comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus with retinopathy and poor visual acuity. Considering the necessity of caregiver’s support to complete the every day’s procedures, most patients would not choose PD as a favoured choice to prevent the OOP cost of caregiver. Compared with HD patients, PD patients with diabetes mellitus or age more than 65 years old also had an increased death rate. All these factors would discourage patients from choosing PD as their renal replacement modality.5

In this study, productivity losses were estimated according to the human capital approach using the reduced future gross income, including lower paid or unpaid production due to seeking medical care and operating the PD apparatus.21 Productivity losses accounted for 31.7% of the overall costs in the HD patients, which is similar to 31.8% in the PD patients. The mean difference of the productivity losses after bootstrap procedures between HD and PD patients was NTD 2539 (table 4). The results reflected that the productivity losses, resulting from the time spent seeking outpatient care and operating the dialysis apparatus were significantly lower in the PD than in the HD patients. The productivity losses in HD patients decreased gradually in the older age groups and were higher than those of PD patients were in the same age group (table 4). Unlike the HD patients, who needed to visit an HD centre three times a week, the PD patients could work freely, spent less time in operating the dialysis apparatus, and had lower productivity losses. When compared with HD, PD is a self-care and time-saving modality, which explains the lower productivity losses. In patients with chronic kidney disease stage 5 near ESRD, facing with numerous decisions across the trajectory of their illness are needed. Using a shared decision-making approach offers a patient-centred method to nudge patients facing health-related decisions, including the choice of HD, PD, kidney transplantation or hospice care. The OPP costs and productivity losses have a significant impact on the quality of lives and cost of healthcare delivery. Exploring the detailed information will provide evidence-based, high-quality decision aids and be able to meet patients’ informational needs. To extend the generalisability of our findings to other national health systems, our result demonstrates that PD modality may appear to be more suitable for its markedly lower productivity losses for countries with a younger dialysis patient population (less than 70 years old), or with a higher value hourly wage or daily wage. The population characteristics, summarised in table 1, serves as a basis for considering extending the results to other populations/medical systems. If the baseline characteristics (demographics and clinical need) are similar across populations, the generalisability seems more convincing.

The results of this study confirmed HD modality had higher OOP costs and productivity losses than PD modality shown in previous studies.12 20 This study also found that productivity losses contributed 15.2% and 16.5% to the total economic burden of HD and PD, respectively, which were higher than 12.4% and 9.8% found in the Brazilian study.20 This discrepancy may reflect the difference in healthcare system in Taiwan, where medical care is mainly financed by NHI, and Brazil, where patients pay OOP for their medical care.

The results of this study have some limitations. First, the difference in the proportion of age groups in HD and PD patients are the major drawback of this study. From the 2016 Annual Report on Kidney Disease in Taiwan, the mean ages of HD and PD commencement in 2014 were 66.7 and 57.3, respectively, which were older than those of HD and PD patients in this cross-sectional study (61.0 and 56.2, respectively, table 1).15 Due to this difference, it was difficult to obtain sampling of these two groups of patients in the similar age range. Therefore, we analysed the results by stratifying into four age groups to compare the differences. Second, the results of this study should be interpreted cautiously. The sample size could not represent the general population of HD and PD patients in Taiwan because the sampled patients were also not randomised, although they were sampled from different parts of Taiwan. Third, the impaired productivity or reduced effectiveness at work associated with HD or PD were not included in this study, so the productivity losses may thus have led to an underestimation. Fourth, when designing a question asking patients about their healthcare utilisation, the optimum recall period is always an issue to tackle. While a shorter recall period of healthcare utilisation may decrease the likelihood of a recall error, at the same time, it also increases the likelihood of missing information. In this study, we chose 12 months as the recall period to make sure all OOP information in the previous year captured in the answer and this possibly caused a recall bias.

In this study, we present a patient interview survey in Taiwan to analyse the OOP costs and productivity losses for HD and PD patients. From a patient’s and societal perspective, the HD patients have higher OOP costs and productivity losses than the PD patients do in the age group less than 70 years old owing to higher productivity losses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ming-Kuhn Ruaan, Dr Su-Chen Lin, Dr Jui-Yuan Hung and Dr Wen-Sheng Ko for their assistance in collecting clinical data.

Footnotes

Contributors: C-HT and Y-MS: study concept and design. H-HC, M-JW, B-GH, J-CT, C-CK, S-PL and T-HC: acquisition of data. C-CK, C-HT and Y-MS: analysis and interpretation. C-HT and Y-MS: drafted the manuscript. H-HC, M-JW, B-GH, J-CT, S-PL and T-HC: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final paper.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University (105TMU-WFH-05).

Disclaimer: C-HT and Y-MS are fully responsible for the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University approved this study (No. 201503057).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data have been included in the paper.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Yang WC, Hwang SJ. Taiwan Society of Nephrology. Incidence, prevalence and mortality trends of dialysis end-stage renal disease in Taiwan from 1990 to 2001: the impact of national health insurance. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:3977–82. 10.1093/ndt/gfn406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2014 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Available: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=CF2EDC7144006740&topn=D39E2B72B0BDFA15 (accessed 15 June 2017).

- 4. Mehrotra R, Chiu YW, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Similar outcomes with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:110–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang YK, Hsu CC, Hwang SJ, et al. A comparative assessment of survival between propensity score-matched patients with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in Taiwan. Medicine 2012;91:144–51. 10.1097/MD.0b013e318256538e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karopadi AN, Mason G, Rettore E, et al. The role of economies of scale in the cost of dialysis across the world: a macroeconomic perspective. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29:885–92. 10.1093/ndt/gft528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kao TW, Chang YY, Chen PC, et al. Lifetime costs for peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in patients in Taiwan. Perit Dial Int 2013;33:671–8. 10.3747/pdi.2012.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roggeri A, Roggeri DP, Zocchetti C, et al. Healthcare costs of the progression of chronic kidney disease and different dialysis techniques estimated through administrative database analysis. J Nephrol 2017;30:263–9. 10.1007/s40620-016-0291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salonen T, Reina T, Oksa H, et al. Cost analysis of renal replacement therapies in Finland. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42:1228–38. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baboolal K, McEwan P, Sondhi S, et al. The cost of renal dialysis in a UK setting–a multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1982–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfm870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hornberger J, Hirth RA. Financial implications of choice of dialysis type of the revised Medicare payment system: an economic analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;60:280–7. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang F, Lau T, Luo N. Cost-effectiveness of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease in Singapore. Nephrology 2016;21:669–77. 10.1111/nep.12668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang YT, Hwang JS, Hung SY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: A national cohort study with 14 years follow-up and matched for comorbidities and propensity score. Sci Rep 2016;6:30266 10.1038/srep30266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haller M, Gutjahr G, Kramar R, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of renal replacement therapy in Austria. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2988–95. 10.1093/ndt/gfq780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. 2016 Annual Report on Kidney Disease in Taiwan. Taipei, Taiwan: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ms W, Iw W, Shih CP, et al. Establishing a platform for battling end-stage renal disease and continuing quality improvement in dialysis therapy in Taiwan-Taiwan Renal Registry Data System (TWRDS). Acta Nephrologica 2011;25:148–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, et al. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:533–44. 10.1681/ASN.2011060607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li PK, Chow KM, Van de Luijtgaarden MW, et al. Changes in the worldwide epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:90–103. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eisenberg JM. Clinical economics. A guide to the economic analysis of clinical practices. JAMA 1989;262:2879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Abreu MM, Walker DR, Sesso RC, et al. A cost evaluation of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in the treatment of end-stage renal disease in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Perit Dial Int 2013;33:304–15. 10.3747/pdi.2011.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liljas B. How to calculate indirect costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 1998;13:1–7. 10.2165/00019053-199813010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Unemployment rate: National Statistics, R.O.C. (Taiwan), 2016. Available: https://www.stat.gov.tw/point.asp?index=3 (accessed 31 Dec 2016).

- 23. Bruns FJ, Seddon P, Saul M, et al. The cost of caring for end-stage kidney disease patients: an analysis based on hospital financial transaction records. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:884–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023062supp001.pdf (139.9KB, pdf)