Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between contraceptive effectiveness of Natural Cycles and users’ previous choice of contraceptive, and to evaluate the impact of shifting from other methods to Natural Cycles on the risk of unintended pregnancy.

Setting

Natural Cycles mobile application.

Participants

16 331 Natural Cycles users in Sweden for the prevention of pregnancy.

Outcome measures

Risk of unintended pregnancy.

Study design

Real world evidence was collected from Natural Cycles users regarding contraceptive use prior to using Natural Cycles and sexual activity while using Natural Cycles. We calculated the typical use 1-year Pearl Index (PI) and 13-cycle failure rate of Natural Cycles for each cohort. The PI was compared with the population PI of their stated previous methods.

Results

For women who had used condoms before, the PI of Natural Cycles was the lowest at 3.5±0.5. For women who had used the pill before, the PI of Natural Cycles was the highest at 8.1±0.6. The frequency of unprotected sex on fertile days partially explained some of the observed variation in PI between cohorts. 89% of users switched to Natural Cycles from methods with higher or similar reported PIs.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of Natural Cycles is influenced by previous contraceptive choice and this should be considered when evaluating the suitability of the method for the individual. We estimate that Natural Cycles usage can reduce the overall likelihood of having an unintended pregnancy by shifting usage from less effective methods.

Keywords: contraception, fertility app, family planning, fertility awareness, information technology, telemedicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study investigates the real-world effectiveness of a fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception in a very large sample of women.

The results have implications for correct usage of the product and for further research.

We do not know the effectiveness of the previously used methods for this cohort and use the US population effectiveness figures reported by Trussell (2011).

In establishing pregnancy status, 207 users (1.3% of sample) who dropped out of the study were lost to follow-up and only some were assumed to be pregnant; however, a post hoc sensitivity analysis demonstrated that even if all these users were assumed to be pregnant, the effectiveness outcomes were not significantly altered.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a surge in the use of fertility awareness-based applications for contraception and family planning. Several studies of varying size, design and quality have investigated the effectiveness of the more popular applications for contraception.1–6 The popularity of these applications has highlighted a significant unmet need for effective non-hormonal alternatives to traditional contraceptive options. Indeed, in a 2017 market research survey via email of 500 UK women between the ages 18 and 45 years, it was found that 49% used a hormonal contraceptive pill out of which 78% stated that they would be interested in an effective non-hormonal alternative (market research survey conducted with 500 women via email in September 2017 by Kantar TNS for Natural Cycles). The development of applications for contraception and family planning is one of the very few genuine innovations within the field of contraception for several decades.

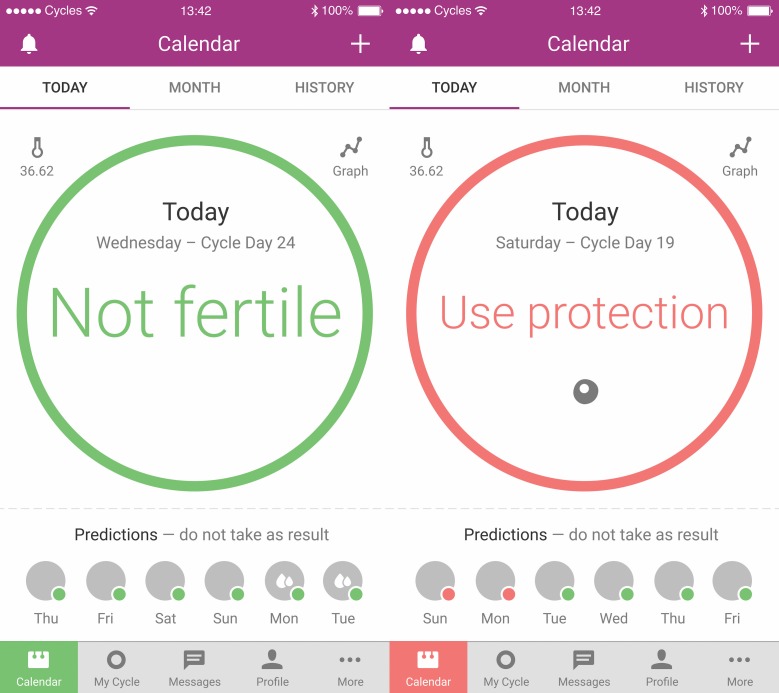

Although there are many applications available for fertility tracking and family planning, Natural Cycles is currently the only mobile application to be certified for use as a medical device (Class IIb) for contraception in Europe. The application is easy to use as a method for preventing pregnancy. A woman measures her temperature on waking with a basal thermometer and enters this into the application. She can also enter the luteinising hormone (LH) test results if available, but this is not essential. The sophisticated algorithm then gives the user either a green day, which means she is not fertile and is able to have unprotected intercourse, or a red day, which means she is possibly fertile and should either abstain from sex or use protection in order to avoid a pregnancy (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visualisation of the fertility data. ‘Today’ fertility view shows either a green or a red day depending on whether the women is not fertile (cannot get pregnant) or must use protection or abstain (in order to prevent a pregnancy). The predictions for upcoming days are the estimates of fertility for planning purposes only. Decisions on the use of protection should be made on the day and not ahead of time.

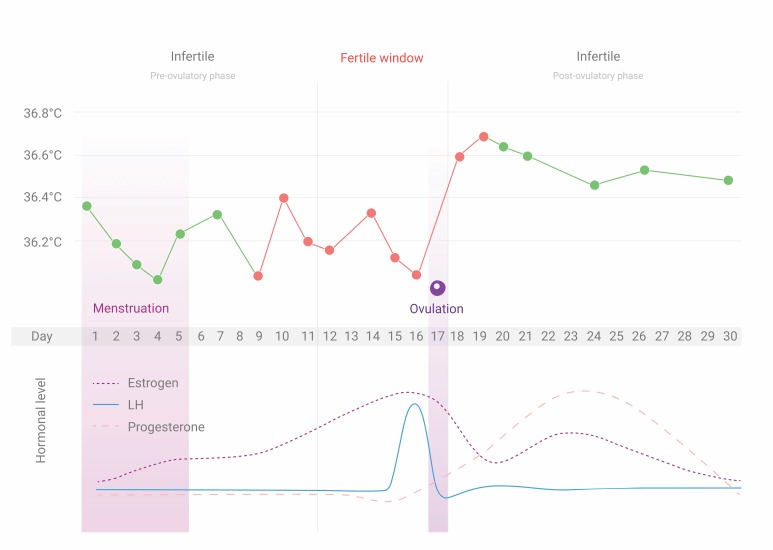

The mechanism of action of the Natural Cycles a pplication has been developed from the traditional basal body temperature method, which is an established fertility awareness-based method of contraception that is up to 99% effective when used correctly and consistently.7 In contrast to the traditional basal body temperature (BBT) method, the a pplication is easy to use, does not require dedicated training and uses a highly sophisticated algorithm for accurate detection and prediction of ovulation.4–6 Ovulation is accurately detected by the a pplication by identification of the physiological increase in BBT that occurs secondary to an ovulation-associated rise in progesterone levels (figure 2). The Natural Cycles application learns the user’s individual pattern of ovulation and uses this information to predict the ovulation day. The application then assigns the fertile window by including the day of ovulation (the oocyte is estimated to survive up to 24 h after ovulation) and the five preceding days because sperm can survive up to 5 days within the female genital tract. In order to account for natural variation in the ovulation day, the application extends the red days by a safety margin either side of the fertile window that is dependent on the user’s individual pattern of ovulation. The number of assigned red days is greatest for users who have less regular cycles and in the first 3 months of using the application, before the aplication gets to know the individual’s cycle. After 3 months of use, women with fairly regular cycles can expect to have approximately 60% green days, where barrier protection is not required to prevent pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Illustration of BBT and hormonal variations throughout an ovulatory cycle. Fertile and non-fertile days as determined by Natural Cycles are marked in red and green, respectively. LH, luteinising hormone.

The real-world effectiveness of the Natural Cycles application has been investigated in a large prospective end-user study including 22 785 women, who logged a total of 18 548 woman-years of data.6 Women who used the Natural Cycles method of contraception were typically around the age of 30, with a regular lifestyle and were able to measure their basal body temperature at least five times per week. The Natural Cycles method of contraception had a 1-year typical use Pearl Index (PI) of 6.8±0.4. The PI was 1.0±0.5 with correct and consistent use (‘Perfect Use’). The 13-cycle typical use failure rate was 8.3% (95% CI 7.8 to 8.9). The effectiveness of Natural Cycles is strongly influenced by user behaviour, particularly the ability of the user to measure basal body temperature on a regular basis, and the ability to either abstain from sex or use condoms on red days. We hypothesised that such behaviours are influenced by previous contraceptive use and that previous contraceptive use could be associated with the real-world effectiveness of Natural Cycles. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the association between previous contraceptive choice and the effectiveness of Natural Cycles. As a secondary aim, we sought to investigate the population-level impact of Natural Cycles on the rates of unintended pregnancies by comparing the cohort-wise effectiveness of Natural Cycles with previous contraceptive choice.

Methods

Study design

This prospective observational study included all women who had registered as paying annual subscribers to Natural Cycles between 1st September 2016 and 30th October 2017 with the intent of preventing a pregnancy. All users in the study consented at registration to the use of their anonymised data for the purposes of research and could withdraw their consent at any time.

We did not include any data from menstrual cycles that started after 28th February 2017. The women were using Natural Cycles as their primary method of contraception, resident in Sweden (determined from the postal address for annual subscribers), aged 18–45 and required to have entered at least 20 days of data (any combination of temperature, LH test, pregnancy test, sexual activity or personal notes) into the application. This last criterion was intended to exclude users who were pregnant at the time of registration and also those who did not have any serious intent of using the application. The users were followed until they had reported a positive pregnancy test, answered a follow-up email or reported menstruation in the application with a final cut-off date of 30th April 2018. The pregnancy status of users who were lost to follow-up was estimated from their temperature measurements and from the point in the cycle at which they dropped out. For a complete explanation of how pregnancy status was assessed, see Berglund-Scherwitzl et al.6

Data collection and analysis

At the time of registration, users were asked the following compulsory questions in order to tune the Natural Cycles algorithm to their needs:

Q1. Have you recently (within last 60 days) used any form of hormonal contraception?

During usage of the application, they were sent an optional in-app question at a random time—but no sooner than 30 days—after registering:

Q2. If ‘No’ to Q1: What form of contraception did you use before starting with Natural Cycles?

Q3. If ‘Yes’ to Q1: What type of hormonal birth control did you use?

Users who did not recently use hormonal contraception may nonetheless have used it as their previous method, hence one of the possible answers to Q2 is ‘Hormonal more than 60 days ago’. The typical use PI of Natural Cycles cohorts were calculated according to previous contraceptives, using the method described in Berglund-Scherwitzl et al.6 The cohort-wise PIs of the previous methods of contraception are not known. In order to investigate the impact of Natural Cycles on the rates of unintended pregnancies, we compared cohort-specific PI against established population-level typical use effectiveness rates.8 We also calculated 13-cycle typical use failure rates using Kaplan-Meier life table analysis. CIs on the 13-cycle failure rates were calculated using the method of Kalbfleisch and Prentice.9

Patient involvement

Although patients were not directly involved in the design of this observational study, the subject of individual suitability for use of the Natural Cycles method for contraception is an area of significant interest from prospective users and medical professionals. This study was designed to provide an evidence-based decision aid for women considering using Natural Cycles for contraception.

Results

The study included 16 331 women resident in Sweden who met the inclusion criteria, contributing an average of 8.0 months of data for a total of 10 748 woman-years of exposure. Fourteen thousand eight hundred and eighty-nine women contributed at least 3 months, 11 515 at least 6 months, 5683 at least 9 months and 2206 at least 12 months. They were aged 18–45 (median=29, mean=30.0±5.0) at sign-up (see supplementary table S1 in supplementary file for further details on age). Six hundred and fifty-eight pregnancies were recorded.

bmjopen-2018-026474supp001.pdf (28.4KB, pdf)

Number of respondents

All women (100%) answered Q1; 6950 women (41%) answered ‘Yes’ and 9381 (59%) ‘No’. Out of the women who answered No to Q1, 6147 (66%) answered Q2 and out of the women who answered Yes to Q1, 5218 (75%) answered Q3. Table 1 lists the number of users in each cohort defined by the answers to Q2 and Q3.

Table 1.

Cohort sizes defined by answers to Q2 and Q3

| Q2 answer | No of users | Percentage of all Q2 respondents |

| Condom | 2411 | 39.2 |

| Hormonal contraceptive* | 1499 | 24.4 |

| Withdrawal | 885 | 14.4 |

| None | 535 | 8.7 |

| Copper IUD | 479 | 7.8 |

| Fertility awareness | 235 | 3.8 |

| Diaphragm | 61 | 1.0 |

| Spermicide | 42 | 0.7 |

| Q3 answer | No of users | Percentage of all Q3 respondents |

| Contraceptive pill** | 4023 | 77.1 |

| Hormonal IUD** | 503 | 9.6 |

| Hormonal ring** | 390 | 7.5 |

| Implant** | 302 | 5.8 |

*Not recently used (>60 days before starting Natural Cycles).

** Recently used (≤60 days before Natural Cycles).

IUD, intrauterine device.

Typical use effectiveness

A 1-year typical use PI of 6.1±0.2 and 13-cycle failure rate of 6.3%±0.6% were computed for the whole sample of 16 331 women. The PI is lower than the previously reported 1-year typical use PI of Natural Cycles of 6.8±0.4.6 Women who had not recently used any hormonal method (n=9381) had a PI of 5.1±0.3 and a 13-cycle failure rate of 5.2%±0.7%. Women who had recently used any hormonal method (n=6950) had a PI of 7.5±0.4 and a 13-cycle failure rate of 8.1%±1.0%. Table 2 lists the typical use PIs and 13-cycle failure rate for each cohort. Cohorts with fewer than 10 pregnancies have been excluded. The best-performing Natural Cycles users were those who used condoms (n=2411, PI 3.5±0.5, 13-cycle failure rate 3.6%±1.0%) prior to starting on Natural Cycles. The worst-performing were those from contraceptive pills (n=4023, PI 8.1±0.6, 13-cycle failure rate 8.7%±1.3%).

Table 2.

Typical-use 1-year PI of Natural Cycles for cohorts of users by method of contraception used prior to Natural Cycles versus expected PI according to population figures

| Contraceptive | 12-Month typical use PI by last method of contraception | 13-Cycle life table pregnancy probability by last method of contraception | Typical use PI for previous contraceptive2 | Difference in PI |

| Male condom | 3.5±0.5 | 3.6±1.0 | 18 | ↓ 14.5 |

| Withdrawal | 6.0±1.0 | 5.4±1.9 | 22 | ↓ 16.0 |

| Copper IUD | 5.4±1.3 | 6.4±3.6 | 0.8 | ↑ 4.6 |

| Fertility awareness* | 7.2±2.1 | 7.4±4.6 | 24 | ↓ 16.8 |

| None | 6.5±1.3 | 7.0±3.1 | 85 | ↓ 78.5 |

| All non-hormonal | 4.8±0.4 | 4.8±0.9 | – | – |

| Previous hormonal method (>60 days prior to Natural Cycles) | 5.6±0.7 | 5.8±1.7 | – | – |

| Contraceptive pill | 8.1±0.6 | 8.7±1.3 | 9 | ↓ 0.9 |

| Hormonal IUD | 5.3±1.3 | 5.4±2.9 | 0.2 | ↑ 5.1 |

| Hormonal ring | 6.2±1.5 | 7.1±4.2 | 9 | ↓ 2.8 |

| All hormonal (<60 days prior to Natural Cycles) | 7.6±0.5 | 8.2±1.2 | – | – |

*Risk varies with specific fertility awareness method. Natural Cycles was not part of this figure.

IUD, intrauterine device.

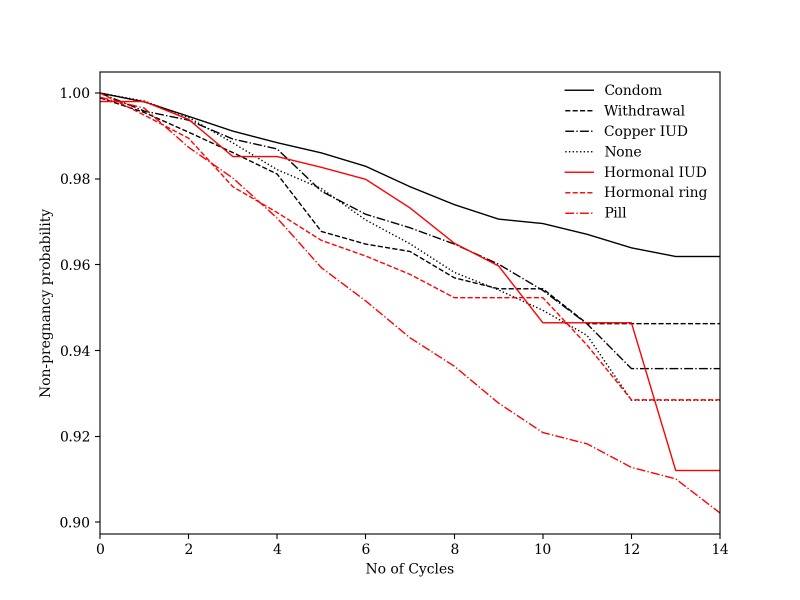

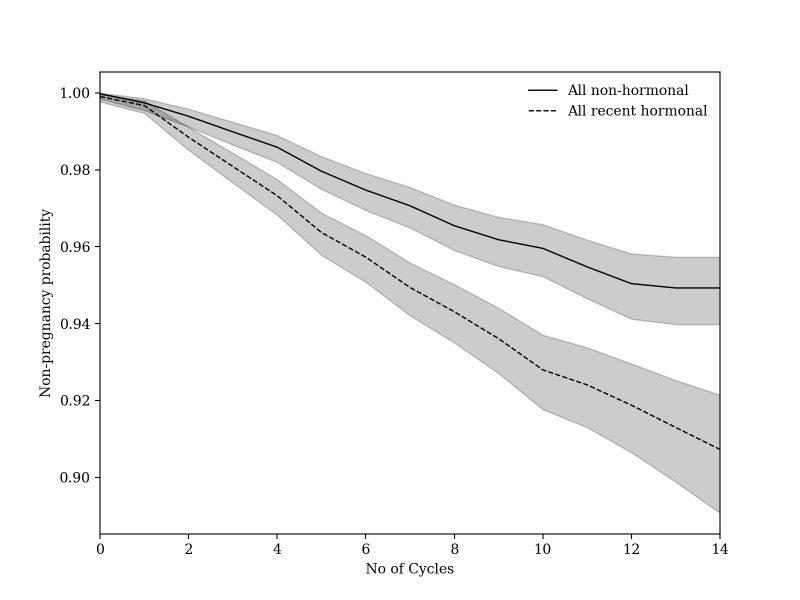

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves (without CIs for the sake of clarity) for all cohorts with at least 15 pregnancies. The condom (black solid line) and pill (red dash-dotted line) cohorts have the highest and lowest failure rates, respectively. Figure 4 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves with CIs for women who recently used any hormonal method (dashed line) and women who used any non-hormonal method (solid line). Women in the latter group are significantly less likely to become pregnant on Natural Cycles.

Figure 3.

Cohort-wise typical use Kaplan-Meier curves of non-pregnancy probability.

Figure 4.

Typical use Kaplan-Meier curves of non-pregnancy probability with CIs for women who recently used any hormonal method (dashed line) versus women who used any non-hormonal method (solid line). IUD, intrauterine device.

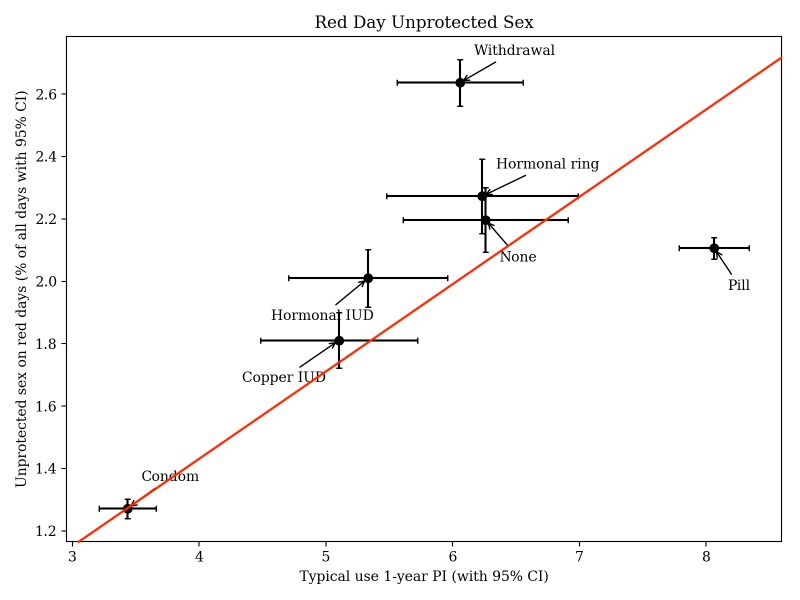

Sexual activity

Differences in cohort-wise effectiveness can be partially explained by looking at users’ self-reported sexual activity. From each user’s data entries, we computed the frequency of unprotected sex on red (possibly fertile) days as a percentage of all days using Natural Cycles. We refer to this is as the risk factor; it is plotted against PI in figure 5 for all cohorts with at least 15 pregnancies. Error bars denote the 95% CIs on risk factor and PI. There is a trend of increasing PI with increasing risk factor (shown in red). Natural Cycles users who previously used condoms as their primary method of contraception have a much lower risk factor and a much lower PI. Those who used withdrawal have an average PI but the highest risk factor; however, it is likely that they are reporting sex with withdrawal as unprotected. Those who used contraceptive pills have a relatively high risk factor and the highest PI.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of frequency of reported red-day unprotected sex (as a % of all days using Natural Cycles) versus typical use PI for cohorts of users by previous choice of contraceptive. Approximate linear trend is shown in red.

Impact of Natural Cycles on likelihood of unintended pregnancy

The last column in table 2 lists the typical use PI for each contraceptive method from many different studies on the US population.8 Out of those users who answered the optional questions (Q2 or Q3), 11% previously used long-acting contraceptive methods, that is, implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs), with much lower PIs than Natural Cycles. The remaining 89% had previously used short-acting methods (or no method) with comparable or higher PI. By ‘comparable’ we mean that the difference is less than 50% of the larger of the two figures: for example in the case of the hormonal ring the difference (9.0–6.2) is less than 50% of 9.0.

Discussion

We investigated the real-world effectiveness of the Natural Cycles application-based method of contraception and found that the PI is lowest for women who had previously used condoms (PI 3.5±0.5) as their primary method of contraception. The PI was highest for those whose previous method was any type of contraceptive pill (PI 8.1±0.6). Those who had recently used any form of hormonal contraception had a higher PI on Natural Cycles (7.6±0.5) than those who had switched to Natural Cycles from a non-hormonal method (PI 4.8±0.4).

The effectiveness of Natural Cycles as a method of contraception may be influenced by a combination of both user-related and method-related factors. User-related factors include level of compliance, particularly with the requirement to use barrier protection or abstain from sex on red (possibly fertile) days, as well as user demographics and cycle characteristics. Method-related factors include the number of falsely attributed green days, which is dependent on accurate detection and prediction of individualised ovulation day, and correct identification of the fertile window. In this study, we did not observe any significant differences in method-related factors between cohorts that could explain the differences in effectiveness. We found significantly better compliance with instructions to use barrier protection on red days in those women who had previously used condoms as their primary method of contraception. This user group reported unprotected sex on fertile days much less frequently than other users, which goes some way to explaining the low PI. We hypothesise that this cohort of women and their partners are more accepting of using condoms on red days than those who previously used hormonal methods. They are likely to have greater familiarity with using condoms and a partner who is accepting of this need. The PI was also low for users who had previously used withdrawal despite these women reporting the highest frequency of unprotected sex on red days. The reason for this observation is not known; however, we speculate that this group may report withdrawal as unprotected and may be skilled at using the withdrawal method due to previous experiences. We observed a PI of 8.1±0.6 for women who had discontinued the pill prior to switching to Natural Cycles. This was higher than the observed PI in the cohort of women who had used other forms of contraception. Women who had discontinued the pill recorded a higher frequency of unprotected sex on red days, suggesting that they are less used to using protection. There were no significant differences in age between cohorts, indicating that age is not a confounding variable. Further research is required to investigate behavioural and demographic differences between cohorts.

It is clear that the cohort-wise effectiveness of Natural Cycles may vary according to user-related factors. By developing our understanding of these factors for each particular cohort of Natural Cycles user, there is the potential to optimise the effectiveness of the method through individualised and focused product-related education. While this can be achieved to a limited extent through development of the instructions for use and personalised messaging through the application, there is an opportunity for respected medical societies to support the correct and appropriate use of the application by providing more detailed guidance on how Natural Cycles should be used and by whom. As the number of users of Natural Cycles grows, healthcare professionals will encounter women using the product with increasing frequency. It is important that in this situation there is an adequate knowledge of the benefits and limitations of the device for different cohorts of women in order that these can be discussed in a clinic.

On a population level, the results of this study suggest that use of the Natural Cycles method for contraception may reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy in cohorts of women who previously used as their primary method the condom, withdrawal or an alternative fertility awareness-based method. Cohorts of women who choose to switch to Natural Cycles from oral contraceptive pills or the hormonal ring may also have a reduced rate of unintended pregnancy, although it is important to note that these users are likely to have been dissatisfied with their previous method. Conversely, women switching to Natural Cycles from IUDs may experience a greatly increased risk of unintended pregnancy. Such findings suggest that further research should be conducted to quantify the population level effects of the Natural Cycles application and the potential positive impact of reduced unintended pregnancy rates on abortion levels.

A limitation of this study is our lack of knowledge about the effectiveness of previous methods of contraception for Natural Cycles users. Due to this limitation, we are unable to quantify the precise improvements in the rates of unintended pregnancy. We are also unable to fully explore the impact of Natural Cycles on user-related factors such as sexual activity levels and motivation to avoid an unintended pregnancy, which could have influenced the typical use effectiveness of the different methods. Future studies will aim to explore the impact of behavioural traits on the measures of effectiveness in Natural Cycles users.

We conclude that use of the Natural Cycles application as a method of contraception is most effective in those who previously relied on condoms and offers an alternative option with similar levels of effectiveness for prevention of pregnancy in those women are dissatisfied with oral contraceptive pills. The redistribution of users towards Natural Cycles from various contraceptives appears to achieve a potential improvement on the overall rate of unintended pregnancy. These preliminary findings motivate further research to explore the behavioural traits of different cohorts and to investigate the impact on abortion rates.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JB contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation. SR and OL contributed to the study design, data interpretation and manuscript preparation. EB-S and RS contributed to the study design, data acquisition and final approval. KG-D and JT contributed to the study design, data interpretation and final approval.

Funding: The study was funded by Natural Cycles Nordic AB. JT acknowledges the support from an infrastructure grant for population research from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, P2C HD047879.

Competing interests: EB-S and RS are the scientists behind the application Natural Cycles and the founders of the company with stock ownership. JB, OL and SR are employed by Natural Cycles Nordic AB. KG-D serves on the medical advisory board of Natural Cycles and has received honorarium for participating in advisory boards and/or giving presentations for matters related to contraception and fertility regulation for Ferring, Exelgyn and Mithra. JT declares explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

Ethics approval: The study protocol wasreviewed and approved by the regional ethic s committee (EPN,Stockholm, diary number 2017/563-31).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional unpublished data from this study.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Freundl G, Frank-Herrmann P, Godehardt E, et al. Retrospective clinical trial of contraceptive effectiveness of the electronic fertility indicator Ladycomp/Babycomp. Adv Contracept 1998;14:97–108. 10.1023/A:1006534632583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simmons RG, Shattuck DC, Jennings VH. Assessing the efficacy of an app-based method of family planning: The dot study protocol. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6:e5 10.2196/resprot.6886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koch MC, Lermann J, van de Roemer N, et al. Improving usability and pregnancy rates of a fertility monitor by an additional mobile application: results of a retrospective efficacy study of Daysy and DaysyView app. Reprod Health 2018;15:37–47. 10.1186/s12978-018-0479-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4. Berglund Scherwitzl E, Lindén Hirschberg A, Scherwitzl R. Identification and prediction of the fertile window using NaturalCycles. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2015;20:403–8. 10.3109/13625187.2014.988210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berglund Scherwitzl E, Gemzell Danielsson K, Sellberg JA, et al. Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2016;21:234–41. 10.3109/13625187.2016.1154143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berglund Scherwitzl E, Lundberg O, Kopp Kallner H, et al. Perfect-use and typical-use Pearl Index of a contraceptive mobile app. Contraception 2017;96:420–5. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO. Fact sheet on family planning / contraception. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/.

- 8. Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404. 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data. New York: Wiley, 2011. https://books.google.se/books?id=BR4Kq-a1MIMC. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026474supp001.pdf (28.4KB, pdf)