Abstract

Objective

Several studies identified neighbourhood context as a predictor of prognosis in ischaemic heart disease (IHD). The present study investigates the relationships of neighborhood-level and individual-level socioeconomic status with the odds of ongoing management of IHD, using baseline survey data from the Korea Health Examinees-Gem study.

Design

In this cross-sectional study, we estimated the association of the odds of self-reported ongoing management with the neighborhood-level income status and percentage of college graduates after controlling for individual-level covariates using two-level multilevel logistic regression models based on the Markov Chain Monte Carlo function.

Setting

A survey conducted at 17 large general hospitals in major Korean cities and metropolitan areas during 2005–2013.

Participants

2932 adult men and women.

Outcome measure

The self-reported status of management after incident angina or myocardial infarction.

Results

At the neighbourhood level, residence in a higher-income neighbourhood was associated with the self-reported ongoing management of IHD, after controlling for individual-level covariates [OR: 1.22, 95% credible interval (CI): 1.01 to 1.61). At the individual level, higher education was associated with the ongoing IHD management (high school graduation, OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.65); college or higher, OR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.12; reference, middle school graduation or below).

Conclusions

Our study suggests that policies or interventions aimed at improving the quality and availability of medical resources in low-income areas may associate with ongoing IHD management. Moreover, patient-centred education is essential for ongoing IHD management, especially when targeted to patients with IHD with a low education level.

Keywords: angina, myocardial infraction, multilevel analysis, MCMC, SES, Korea

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is among the first to examine the association between neighborhood-level and individual-level socioeconomic status (SES) and ongoing management of ischaemic heart disease in Asian countries.

Our study benefitted from the use of population-based samples, which enabled a multilevel analysis based on the neighborhood-level SES.

However, our findings were limited by the cross-sectional study design, use of survey data and risk of selection bias.

Introduction

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD), the current leading cause of death in Western countries, is rapidly becoming the leading cause of death in developing countries.1 To reduce the mortality associated with IHD, researchers and clinicians have stressed the importance of patient management. Based on evidence demonstrating that medication adherence and behavioural lifestyle changes improved prognosis and retarded disease progression, guidelines for secondary IHD prevention suggest that patient management should comprise pharmacological treatments (eg, antiplatelet therapy, beta-blocker therapy) or lifestyle modifications (eg, weight control, smoking cessation, blood pressure management).2 3

Earlier research suggests that the management of post-IHD may differ by socioeconomic status (SES). Notably, the lower rates of mortality among patients with IHD with a high SES4 may be attributable to the availability of better care,5 better adherence to therapy, better self-monitoring6 and more rapid implementation of behavioural lifestyle changes,7 which are facilitated by economic, educational and social resources. Independent of the individual-level SES, neighbourhood contexts also play critical roles in various health outcomes, including IHD-related outcomes.8 9 Several previous studies have shown that residence in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods was associated with a greater risk of IHD10 11 and shorter survival duration.12 13 However, few studies have examined the association between the neighbourhood SES and IHD management.

To our knowledge, no study has addressed this association in South Korea (hereafter Korea) or another Asian country. Although the IHD-related mortality rate in 2011 remained lower in Korea (42 per 100 000 individuals) than in Western countries, the incidence of IHD in Korea has increased by 60% during the past decade14 consequent to increases in body mass index values and an increasingly westernised diet among middle-aged adults.15 Secondary IHD mortality may be significantly reduced by ongoing IHD management involving both proper quality treatment and lifestyle modification, which may be shaped by neighbourhood contexts as well as individual characteristics. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the individual-level and neighborhood-level SES as the main determinants of ongoing IHD management in Korea, using baseline data from a large population-based cohort study with a multilevel framework.

Methods

Data source

We used baseline survey data from the Health Examinees-Gem (HEXA_G) study, which was constructed by dropping inconsistent data collected during pilot HEXA survey periods. The original HEXA, which is part of the Korean Genome Epidemiology Study (KoGES),16 was a large-scale genomic cohort study of 1 69 722 adults aged 40–69 years living in major Korean cities and metropolitan areas. Samples were recruited from 38 health examination centres and training hospitals (mainly general hospitals) during 2004–2013.17 Eligible participants who visited the participating sites for biannual health check-ups, which were covered in full by the National Health Insurance Program were asked to respond voluntarily to an interview-based survey conducted by well-trained interviewers using a structured questionnaire. The survey collected information about sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, medication usage, family history and health/lifestyle behaviours. More detailed information about the HEXA cohort study can be found elsewhere.16 17 The HEXA-G dataset comprised 139 345 participants [men: 46 977 (33.7%); women: 92 368 (66.3%)]. Participants were excluded because of inconsistencies in data quality control, biospecimen collection, a short duration of study participation at 21 centres that participated in a pilot study, or the withdrawal of provision of personal information for studies. The original HEXA and HEXA-G were deidentified for research.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design and conduct of this study. The results will not be disseminated to study participants.

Study outcome

The outcome of the study was the self-reported current management status after incident angina or myocardial infarction. To identify participants with a history of IHD, the survey included the yes/no question of ‘Have you ever been diagnosed with angina or myocardial infarction by a medical doctor in a medical facility?’ The sub-population that responded ‘yes’ then answered a subquestion regarding the current status of disease management for which the following options were available: (a) ‘condition has been good or improved due to management’; (b) ‘currently managed and treated’; (c) ‘was previously managed but is now neglected’ and (d) ‘neither managed nor treated.’ We dichotomised these responses as ‘ongoing management’ by combining (a) with (b) versus ‘failure of ongoing management’ (reference) by combining (c) with (d), respectively.

Neighborhood-level SES variables

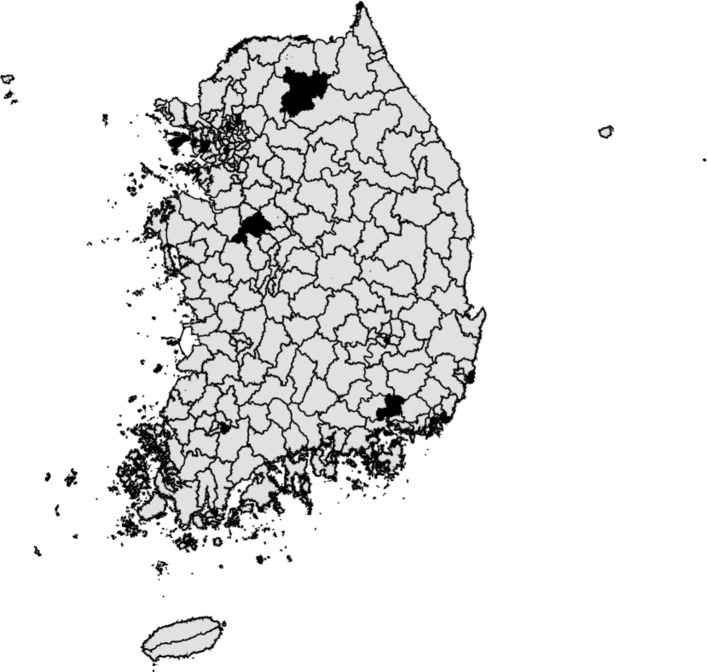

The main neighborhood-level SES variables were (1) the regional median income status and (2) the regional mean percentage of college graduates. Seventeen neighbourhoods were defined as 17 major cities and metropolitan areas (mean population: 201 210, range: 115 000–574 000) associated with 17 large general hospitals (figure 1). The total catchment area of these hospitals covered 6.6% of the total Korean population. We obtained neighborhood-level SES data from a nationally and regionally representative dataset, Korea Community Health Survey (https://chs.cdc.go.kr/chs/index.do), which has been conducted in 253 communities annually since 2008. This survey aims to estimate regional patterns of disease prevalence and morbidity, as well as to understand the personal lifestyle and health behaviour.18 An average of 800–900 adults (age: ≥19 years) who resided in each neighbourhood were selected using the probability proportional to sampling and systematic sampling methods. The sampling strategies are described in more detail elsewhere.18 We calculated exogenous neighborhood-level SES measures using regional mean centering of the percentage of college graduates and median centering of the income status of the survey years. We then linked the regional SES indicators to our main dataset using the neighbourhood identifier and the year variable. A comparison of sociodemographic characteristics between neighbourhoods included and not included in the study revealed that the former was comprised of younger (age: 49.2 vs 52.9 years), more highly educated (college graduates: 43.9% vs 33.0%) and wealthier (the top 25% of household incomes: 30.9% vs 27.8%) population.

Figure 1.

Study areas of 17 major cities and counties in the Korea HEXA-Gem dataset, 2005–2013.

Individual-level SES variables

Educational level was categorised into middle school or lower, high school graduation or college graduation or higher. Income was measured by collapsing the data into four categories: <1, 1–2, 2–4 and ≥4 million Korean won (M KRW).

Covariates

The individual-level covariates included sex, age, marital status occupation and comorbidities. Age was categorised into 40–50, 51–60 or 61+years. Marital status was dichotomised into living with a spouse or not. Occupation was categorised as white collar, blue collar, housewife or other. Comorbidities were defined as the presence of hypertension, diabetes or hyperlipidaemia at the time of the survey.

Statistical analysis

Two-level multilevel logistic regression models were fitted with individuals (level 1) nested within neighbourhoods (level 2) to estimate the contributions of the individual-level and neighborhood-level factors simultaneously. Random intercept models were fitted for the whole study samples to correct for cluster effects of the individual variables within the same neighbourhood according to the neighbourhood identifier in the model. We used the command runmlwin to run MLwiN within Stata V.14).19 This command enables researchers to fit multilevel models more quickly with MLwiN by taking advantage of the multilevel dataset analysis features included in Stata.19 MLwiN was used to fit a binomial logit response model to an estimation using the iterative generalized least squares and second-order penalised quasi-likelihood (PQL2).

Estimates obtained using the above-described methods are known to exhibit a bias for discrete responses20; therefore, we fitted our final model using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) function. Additionally, we adopted the Bayesian estimation function to ensure the accuracy of the estimates and their standard errors, as a small sample size at level 2 can lead to biased estimates.21 22 The MCMC was conducted to burn-in for 500 simulations, which yielded distribution starting values to discard, and subsequently to proceed for 5000 additional simulations to obtain a precise estimate and distribution of interest. Once the convergence diagnostics were confirmed, the ORs and 95% credible intervals (CIs) were presented in a Bayesian framework. We created separate missing dummy categories to retain the missing cases in income (n=295), occupation (n=265) and other covariate data (n=35) in the regression analysis. Due to of little interpretive value, the results for the category were not reported. We did not stratify the analyses by gender because a Chow test [47] failed to detect significant differences in the slopes and intercepts of the gender-stratified regressions [F (1, 2,364)=0.95, p=0.3309].

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of participants with IHD from the HEXA-Gem dataset (n=2932), stratified by self-reported IHD management. Men had higher proportions of self-reported ongoing management than women (85.9% vs 75.5%). Participants of younger groups had higher proportions of failures of ongoing IHD management (40–49: 29.5% vs. 50–59: 21.3% vs. 60–69: 15.2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample from the Korea HEXA-Gem dataset (n=2932), 2005–2013, stratified by self-reported ongoing management of post-ischaemic heart disease

| Individuals | Ongoing management | |||||

| Yes (n=2366, 80.7%) | No (n=566, 19.3%) | |||||

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | Men | 1261 | 85.9 | 207 | 14.1 | * |

| Women | 1105 | 75.5 | 359 | 24.5 | ||

| Age (years) | 40–49 | 248 | 70.5 | 104 | 29.5 | * |

| 50–59 | 904 | 78.7 | 245 | 21.3 | ||

| 60–69 | 1214 | 84.8 | 217 | 15.2 | ||

| Education | ≤Middle school | 987 | 77.8 | 281 | 22.2 | * |

| High school | 868 | 82.0 | 191 | 18.0 | ||

| ≥College | 487 | 84.3 | 91 | 15.7 | ||

| Missing | 24 | 85.7 | 3 | 11.1 | ||

| Income (million Korean won) | <1 | 779 | 83.1 | 159 | 16.9 | * |

| 1–2 | 588 | 80.8 | 140 | 19.2 | ||

| 2–4 | 418 | 78.3 | 116 | 21.7 | ||

| ≥4 | 581 | 79.4 | 151 | 19.3 | ||

| Missing | 204 | 69.2 | 91 | 30.9 | ||

| Occupation | White collar | 618 | 78.8 | 166 | 21.2 | * |

| Blue collar | 359 | 81.8 | 80 | 18.2 | ||

| Housewife | 702 | 76.5 | 216 | 23.5 | ||

| Other | 466 | 88.6 | 60 | 11.4 | ||

| Missing | 221 | 83.4 | 44 | 16.6 | ||

| Marital status | Living with spouse | 2073 | 80.9 | 488 | 19.1 | |

| Living without spouse | 293 | 79 | 78 | 21.0 | ||

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 1104 | 84.5 | 202 | 15.5 | * |

| No hypertension | 1262 | 77.6 | 364 | 22.4 | ||

| Diabetes | 465 | 85.3 | 80 | 14.6 | * | |

| No diabetes | 1901 | 79.6 | 486 | 20.4 | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | 476 | 79.7 | 121 | 20.3 | ||

| No hyperlipidaemia | 1890 | 80.9 | 445 | 19.1 | ||

| Neighbourhoods | Mean | SD |

| Neighborhood-level income status | 0.46 | 0.98 |

| Neighborhood-level % of college graduates or higher | 0.10 | 0.07 |

*Differences between two groups for the all variables were considered significant at a p value <0.05.

Table 2 presents the results of the two-level multilevel logistic regression models for ongoing IHD management. In model 1, the odds of ongoing management were higher for those with IHD who resided in higher-income neighbourhoods, with an OR of 1.39 (95% CI: 1.15 to 1.66). In model 2, a higher individual education level was associated with ongoing IHD management, with ORs of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.06 to 1.66) and 1.52 (95% CI: 1.14 to 2.02) for high school graduation and college graduation or higher, respectively, compared with those with a middle school or lower education. However, no significant associations were observed between an individual’s income group and the likelihood of self-reported ongoing management. In model 3, the neighborhood-level income status remained significantly associated with self-reported ongoing management even after adjusting for individual-level factors (OR: 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.61). In this model, however, the association of residence in a neighbourhood with a high percentage of college graduates with self-reported ongoing IHD management was not statistically significant. Finally, all models exhibited significant between-neighbourhood variance.

Table 2.

Estimations from the two-level multilevel logistic regression models of self-reported ongoing management among ischaemic heart disease survivors in the Korea HEXA-Gem dataset, 2005–2013

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| OR (95% credible interval) | OR (95% credible interval) | OR (95% credible interval) | |

| Fixed parameters | |||

| Sex (ref. female) | |||

| Male | 1.83 (1.38 to 2.39) | 1.81 (1.37 to 2.32) | |

| Age (years; ref. 40– 49) | |||

| 50–59 | 1.57 (1.16 to 2.07) | 1.57 (1.14 to 2.07) | |

| 61–69 | 2.19 (1.60 to 2.94) | 2.19 (1.56 to 2.93) | |

| Education (ref. ≤middle school) | |||

| High school | 1.35 (1.06 to 1.66) | 1.33 (1.08 to 1.65) | |

| ≥College | 1.52 (1.14 to 2.02) | 1.63 (1.22 to 2.12) | |

| Income (ref. <1 million Korean won) | |||

| 1–2 million | 0.89 (0.50 to 1.49) | 0.88 (0.37 to 1.48) | |

| 2–4 million | 1.09 (0.63 to 1.76) | 1.14 (0.66 to 1.87) | |

| ≥4 million | 1.26 (0.85 to 1.81) | 1.07 (0.70 to 1.65) | |

| Marital status (ref. living with spouse) | |||

| Living without spouse | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | 1.09 (0.80 to 1.44) | |

| Occupation (ref. white collar) | |||

| Blue collar | 1.11 (0.79 to 1.53) | 1.11 (0.81 to 1.50) | |

| Housewife | 1.13 (0.84 to 1.48) | 1.12 (0.85 to 1.46) | |

| Other | 1.42 (1.00 to 1.97) | 1.42 (0.99 to 1.97) | |

| Hypertension (ref. no) | |||

| Yes | 1.49 (1.20 to 1.84) | 1.49 (1.21 to 1.80) | |

| Diabetes (ref. no) | |||

| Yes | 1.21 (0.91 to 1.58) | 1.20 (0.91 to 1.57) | |

| Hyperlipidaemia (ref. no) | |||

| Yes | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.23) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.19) | |

| Neighborhood-level income status | 1.39 (1.15 to 1.66) | 1.22 (1.01 to 1.61) | |

| Neighborhood-level % of college graduates or higher | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.30) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.41) | |

| Random parameters | |||

| Between-neighborhood variance | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.32) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.37) | 0.16 (0.03 to 0.46) |

| Deivance Information Criterion (DIC) | 2853.90 | 2756.97 | 2754.86 |

Model 1 included the neighborhood-level SES only; model 2 included individual-level factors only; model 3 included all individual. All models were controlled for year dummies.

Discussion

According to our findings, residence in a neighbourhood with a one-unit higher income was associated with a 22% higher likelihood of self-reported ongoing IHD management, compared with residence in a neighbourhood with a lower income status. By contrast, at the individual level, a higher income was not significantly associated with self-reported ongoing IHD management. However, a higher individual education level was associated with a higher likelihood of self-reported ongoing IHD management.

Previous studies have found that a lower neighbourhood SES was associated with a higher risk of IHD10 11 and a shorter survival duration after incident IHD.12 13 Consistent with those reports, our study showed an association of the neighbourhood SES with ongoing IHD management that was independent of individual-level factors. We attribute this association to several factors. First, residents of higher-income neighbourhoods may have greater access to higher quality medical resources, such as physicians or primary care clinics near their homes, regardless of individual income.23 Second, residents in higher-income neighbourhoods may enjoy a more favourable social environment for IHD management, which might include an increased interest in health maintenance and a greater amount of social support from neighbours.24 Third, residents of lower-income neighbourhoods might have reduced access to health-oriented features such as recreation spaces and walkable environments25 and stores that sell healthy foods,26 concomitant with increased access to stores selling cigarettes and/or alcohol27 and exposure to other environmental stressors. These factors may have important implications for self-care practices.

At the individual SES level, our study found that the education level was significantly associated with ongoing IHD management, whereas the income status was not. Similarly, previous studies also reported that IHD management may vary according to an individual’s SES, and suggested that the survivors with lower income and education levels might fail to manage themselves appropriately because of (a) a lack of knowledge related to prevention and healthy habits,28 (b) limited access to care or drugs due to economic constraints29 and (c) a lack of willingness or resources to change their lifestyles.7Patient education has been identified as an important factor in terms of the understanding of a specific disease process, medication management and adherence and reported efficacies and side effects.3 Previous studies demonstrated improved adherence to suggested management among patients with IHD with higher education levels,30 whereas patients with lower education levels may not adhere to guidelines because of a lack of knowledge or understanding about their disease. Alternatively, our study findings may reflect suboptimal doctor–patient communication due to the exceptionally short consultation times with physicians in Korea, which are generally restricted to 2–3 min because of the lack of physicians and fee-for-service payment in the Korean healthcare system.31 This restriction may stunt ongoing IHD management, especially among patients with lower education levels. Accordingly, our findings suggest that individualised education could maximise IHD management outcomes.

Our finding that the individual-level income status and ongoing IHD management were not associated may imply that economic barriers to care or drugs do not determine the ongoing management of this condition. However, previous studies have shown that economically disadvantaged patients might be more likely to decline follow-up procedures or prescribed medications because economic constraint.5 29 Our favourable study finding of no significant income inequality might therefore be explained by the universal healthcare coverage benefits and medical subsidies provided to lower-income populations in Korea.31

Our study had several limitations of note. First, our cross-sectional study was unable to determine the causal relationship between our main exposures (eg, individual-level and neighborhood-level SES) and the self-reported management of IHD. Second, our study used self-reported survey data, which may have been biased by misclassification due to participants’ misunderstanding or social desirability. Additionally, the participants’ responses regarding ongoing IHD management may not have been confirmed by medical professionals whether the received treatment or participants’ adherence to therapy was clinically appropriate. Third, we were not able to control for severity of IHD and time lapsed the acute event because of data limitations. Fourth, selection bias may have been introduced by non-random survey participation and attrition. Disadvantaged individuals were less likely to participate regular health examinations and were more likely to drop out in the survey, possibly due to a failure of ongoing management. This bias would have led to underestimating the likelihood of failure of ongoing management among disadvantaged individuals. Fifth, we assumed that most participants visited the general hospitals within the region they lived. This assumption is highly plausible, given the improved accessibility to the health examination service in Korea contexts, as the National Health Insurance Program provides free regular health examinations and medical facilities within and between regions exhibit minimal variations in examination quality.32 However, we could not completely exclude the possibility that participants may have visited general hospitals in other neighbourhoods to seek better-quality evaluations. Despite these limitations, however, one strength of our study was the use of population-based samples, which enabled a multilevel analysis by linking neighborhood-level SES from the nationally and regionally representative dataset. By contrast, most previous studies used hospital data, which frequently lack information about the individual’s SES and neighbourhood characteristics.33 Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to examine the association between individual-level and neighborhood-level SES and IHD management in an Asian country.

In conclusion, our study findings provide an opportunity to improve ongoing IHD management by identifying the neighborhood-level and individual-level factors, which are associated with SES-related and geographical inequalities in IHD mortality. Our results suggest that policies or interventions intended to improve the quality and availability of medical resources in low-income areas might also effectively reduce inequalities in management and, ultimately, mortality. Moreover, our data suggest that patient-centred education is required to ensure ongoing IHD management and reduce related mortality, particularly among patients with a low education level.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

J-KL and DK contributed equally.

Contributors: JH: analysed the data; drafted, reviewed and edited the manuscript and contributed to the discussion. JKL, DK: supervised the study. JO, HYL, JYC, SK, SVS: reviewed and edited the manuscript and contributed to the discussion.

Funding: This work was supported by a Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004-E71004-00, 2005-E71011-00, 2005-E71009-00, 2006-E71001-00, 2006-E71004-00, 2006-E71010-00, 2006-E71003-00, 2007-E71004-00, 2007-E71006-00, 2008-E71006-00, 2008-E71008-00, 2009-E71009-00, 2010-E71006-00, 2011-E71006-00, 2012-E71001-00 and 2013-E71009-00).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea (IRB No. 0608-018-179).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sharing of HEXA is available through the website of the Korea National Institute of Health (http://www.nih.go.kr/NIH/cms/content/eng/03/65203_view.html#menu4_1_2).

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 2001;104:2855–64. 10.1161/hc4701.099488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:e44–e164. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2014;130:1749–67. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Molshatzki N, Drory Y, Myers V, et al. Role of socioeconomic status measures in long-term mortality risk prediction after myocardial infarction. Med Care 2011;49:673–8. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philbin EF, McCullough PA, DiSalvo TG, et al. Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of the use of invasive procedures after acute myocardial infarction in New York State. Circulation 2000;102(19 Suppl 3):III-107–0. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.suppl_3.III-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goldman DP, Smith JP. Can patient self-management help explain the SES health gradient? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:10929–34. 10.1073/pnas.162086599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lantz PM, Lynch JW, House JS, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health change in a longitudinal study of US adults: the role of health-risk behaviors. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:29–40. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00319-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steenland K, Henley J, Calle E, et al. Individual- and area-level socioeconomic status variables as predictors of mortality in a cohort of 179,383 persons. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:1047–56. 10.1093/aje/kwh129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sundquist K, Winkleby M, Ahlén H, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic environment and incidence of coronary heart disease: a follow-up study of 25,319 women and men in Sweden. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:655–62. 10.1093/aje/kwh096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Merlo J, Ohlsson H, Chaix B, et al. Revisiting causal neighborhood effects on individual ischemic heart disease risk: a quasi-experimental multilevel analysis among Swedish siblings. Soc Sci Med 2013;76:39–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foraker RE, Patel MD, Whitsel EA, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disparities and 1-year case fatality after incident myocardial infarction: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Community Surveillance (1992-2002). Am Heart J 2013;165:102–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaix B, Rosvall M, Merlo J. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and residential instability: effects on incidence of ischemic heart disease and survival after myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 2007;18:104–11. 10.1097/01.ede.0000249573.22856.9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. OECD. Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators: OECD publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suh I, Oh KW, Lee KH, et al. Moderate dietary fat consumption as a risk factor for ischemic heart disease in a population with a low fat intake: a case-control study in Korean men. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:722–7. 10.1093/ajcn/73.4.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim Y, Han BG. KoGES group. Cohort Profile: The Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Consortium. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:e20 10.1093/ije/dyv316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shin S, Lee HW, Kim CE, et al. Egg Consumption and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in Korean Adults: Results from the Health Examinees Study. Nutrients 2017;9:687 10.3390/nu9070687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang YW, Ko YS, Kim YJ, et al. Korea Community Health Survey Data Profiles. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2015;6:211–7. 10.1016/j.phrp.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leckie G, Charlton C. Runmlwin-a program to Run the MLwiN multilevel modelling software from within stata. Journal of Statistical Software 2013;52:1–40.23761062 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Snijders TA. Multilevel analysis. International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science: Springer, 2011:879–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maas CJM, Hox JJ. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology 2005;1:86–92. 10.1027/1614-2241.1.3.86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McNeish DM, Stapleton LM. The effect of small sample size on two-level model estimates: a review and illustration. Educ Psychol Rev 2016;28:295–314. 10.1007/s10648-014-9287-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kapral MK, Wang H, Mamdani M, et al. Effect of socioeconomic status on treatment and mortality after stroke. Stroke 2002;33:268–75. 10.1161/hs0102.101169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med 2006;29:377–87. 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, et al. Neighborhood built environment and income: examining multiple health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1285–93. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mobley LR, Root ED, Finkelstein EA, et al. Environment, obesity, and cardiovascular disease risk in low-income women. Am J Prev Med 2006;30:327–32. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cantrell J, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Pearson JL, et al. The impact of the tobacco retail outlet environment on adult cessation and differences by neighborhood poverty. Addiction 2015;110:152–61. 10.1111/add.12718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonaccio M, Bonanni AE, Di Castelnuovo A, et al. Low income is associated with poor adherence to a Mediterranean diet and a higher prevalence of obesity: cross-sectional results from the Moli-sani study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001685 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forsberg PO, Li X, Sundquist K. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and statin medication in patients with myocardial infarction: a Swedish nationwide follow-up study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:8 10.1186/s12872-016-0319-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kalichman SC, Catz S, Ramachandran B. Barriers to HIV/AIDS treatment and treatment adherence among African-American adults with disadvantaged education. J Natl Med Assoc 1999;91:439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jones RS. Health-care reform in Korea. OECD Economic Department Working Papers 2010:1. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cho B, Lee CM. Current situation of national health screening systems in Korea. Journal of the Korean Medical Association 2011;54:666–9. 10.5124/jkma.2011.54.7.666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shen JJ, Wan TT, Perlin JB. An exploration of the complex relationship of socioecologic factors in the treatment and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in disadvantaged populations. Health Serv Res 2001;36:711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.