Significance

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is an incurable childhood cancer with a median survival of less than 1 y. Characterization of druggable targets in this disease remains a longstanding goal, as no pharmacological agents have proven efficacy in this malignancy. We recently identified the menin inhibitor, MI-2, as exhibiting potent antitumor activity in preclinical models of DIPG. Here, we show that MI-2 exerts its activity in glioma largely independent of its ability to target the epigenetic regulator menin, but instead by disrupting cholesterol homeostasis through direct inhibition of the cholesterol biosynthesis enzyme, lanosterol synthase, revealing this metabolic enzyme as an actionable vulnerability in glioma and implicating cholesterol homeostasis as an attractive pathway to target in malignant gliomas.

Keywords: glioma, MI-2, menin inhibitor, target identification, lanosterol synthase

Abstract

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) remains an incurable childhood brain tumor for which novel therapeutic approaches are desperately needed. Previous studies have shown that the menin inhibitor MI-2 exhibits promising activity in preclinical DIPG and adult glioma models, although the mechanism underlying this activity is unknown. Here, using an integrated approach, we show that MI-2 exerts its antitumor activity in glioma largely independent of its ability to target menin. Instead, we demonstrate that MI-2 activity in glioma is mediated by disruption of cholesterol homeostasis, with suppression of cholesterol synthesis and generation of the endogenous liver X receptor ligand, 24,25-epoxycholesterol, resulting in cholesterol depletion and cell death. Notably, this mechanism is responsible for MI-2 activity in both DIPG and adult glioma cells. Metabolomic and biochemical analyses identify lanosterol synthase as the direct molecular target of MI-2, revealing this metabolic enzyme as a vulnerability in glioma and further implicating cholesterol homeostasis as an attractive pathway to target in this malignancy.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a uniformly fatal brain tumor that remains the leading cause of brain tumor death in children (1). No drugs have shown efficacy in this malignancy, despite >250 clinical trials. Recent exome-sequencing studies have revealed oncogenic drivers in DIPG, most notably somatic hotspot mutations in histone H3, leading to a lysine-27 to methionine substitution (H3K27M) in >80% of DIPG tumors (2, 3). This discovery has facilitated the development of preclinical animal models of DIPG (4–6); however, the H3K27M mutation is not yet directly targetable, and thus there remains a need to identify actionable vulnerabilities in these tumors.

To this end, we recently identified a small molecule, menin inhibitor MI-2 (7), as a potential therapy for DIPG in preclinical animal models of this malignancy (4). Subsequently, work by others demonstrated promising antitumor effects of a structurally similar analog (MI-2-2) (8) in patient-derived adult glioma xenograft models (9, 10), pointing toward antiglioma activity, which likely extends beyond DIPG tumors harboring the H3K27M mutation and broadening the potential applicability of MI-2 and its analogs.

MI-2 was developed as a menin inhibitor for use in leukemia, acting by disrupting the interaction between menin and its binding partner MLL1 (mixed lineage leukemia 1) (7), a histone-methyltransferase that positively regulates gene expression by establishing methylation at histone H3 lysine-4 (H3K4) (11). In certain leukemias, MLL1 undergoes chromosomal rearrangement, leading to generation of a fusion protein (MLL-fusion leukemia), which drives oncogenic transcription (11). Importantly, the N-terminal portion of MLL fusions interact with menin to remain chromatin-bound (12), and blocking this interface using MI-2, or other menin inhibitors targeting the same interface (13), leads to loss of oncogenic gene transcription, suppression of cell growth, and cell differentiation (7).

How MI-2 exerts an antitumor effect in gliomas remains unknown. Neither driver mutations in menin, nor MLL fusions occur in adult glioma or DIPG (2, 3, 14), and the role of wild-type menin in driving oncogenic gene transcription in different glioma subtypes has not been systematically evaluated. Whether the mechanism of MI-2 activity is shared in different molecularly distinct glioma subtypes such as DIPG and adult glioma remains to be determined. Here, we set out to characterize the mechanism of action of MI-2, reasoning that this knowledge would reveal an important pathway vulnerability in these tumors.

Results

Menin-Independent Activity of MI-2 in Glioma.

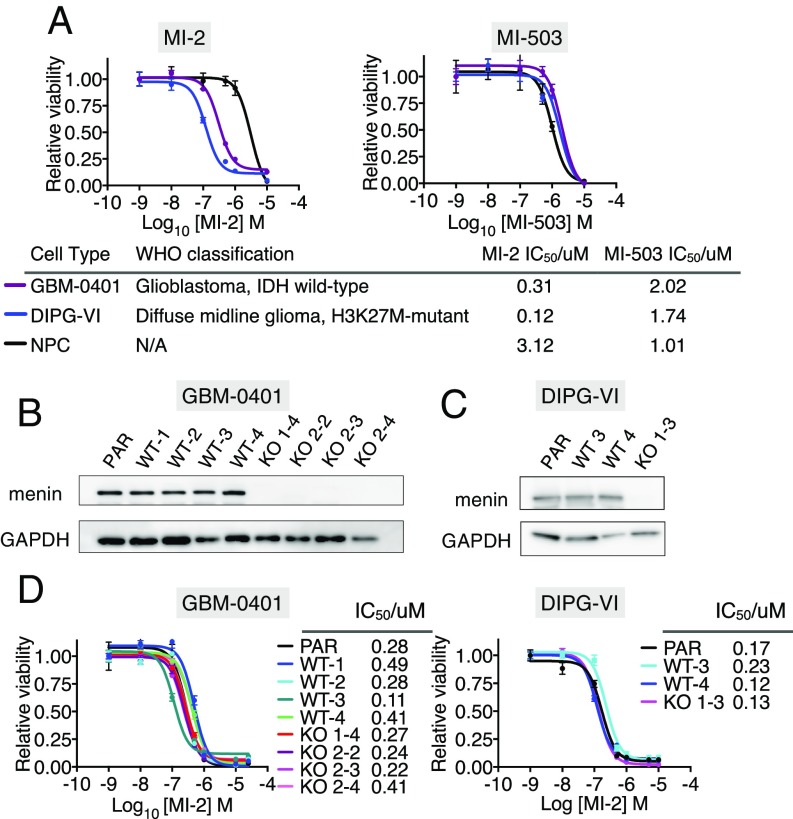

Since the development of MI-2, novel menin inhibitors have been developed with increased potency at disrupting the menin–MLL interface in biochemical and cellular assays (13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). To further explore the importance of the menin–MLL interaction for glioma cell growth, we treated DIPG and adult glioma patient-derived cell lines (DIPG-VI and GBM-0401, respectively) with MI-2 and a more potent, structurally distinct inhibitor of the menin–MLL interface called MI-503 (13) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We reasoned a more potent menin–MLL inhibitor might exhibit increased activity in glioma cells if this interaction were critical in this cellular context, and could also represent a more powerful tool to probe downstream mechanisms. To our surprise, MI-2 was up to 15-fold more potent in glioma cell-lines than MI-503, and notably there was no therapeutic window between normal neural progenitors (NPCs) and tumor cell lines with MI-503 in dose-inhibition viability assays (Fig. 1A). The superior activity of MI-2 in glioma cells compared with MI-503 led us to speculate that the mechanism of action of MI-2 may be menin-independent in this setting.

Fig. 1.

(A) Dose inhibition curves of adult glioma (GBM-0401) and DIPG (DIPG-VI) cell-lines and human NPCs treated with MI-2 and MI-503. IC50 values and World Health Organization (WHO) classification of glioma cell lines shown. IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase. (B) Western blot of CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited MEN1-KO GBM-0401 cell lines and controls. KO 1–4 generated with sgRNA targeting MEN1 exon 4. KO 2–2, 2–3, 2–4 generated with sgRNA targeting MEN1 exon 7. WT1–WT4 generated with control sgRNA targeting nonhuman sequence (Renilla luciferase). Parental cell line (PAR) not transduced with sgRNA. (C) Western blot of CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited MEN1-KO DIPG-VI cell line and controls. KO 1–3 generated with sgRNA targeting MEN1 exon 4. WT3 and WT4 were generated with control sgRNA targeting nonhuman sequence (Renilla luciferase gene). PAR not transduced with sgRNA. (D) Dose-inhibition curves of MEN1 wild-type cells (parental cells and cells transduced with sgRNA targeting Renilla luciferase) and KO cells (transduced with MEN1 targeted sgRNA) treated with MI-2 for 7 d.

To formally test this hypothesis, we generated multiple MEN1 knockout (KO) clones of glioma cells, using CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig. 1 B and C), and compared their sensitivity to MI-2 with their MEN1 wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1D). Cells were stably transduced with Cas9, followed by transduction with either sgRNAs targeting the MEN1 gene or, as a control, targeting Renilla luciferase (Fig. 1 B and C). Remarkably, MI-2 retained nanomolar potency in MEN1 KO clones, with IC50 concentrations comparable to those of wild-type clones (transduced with sgRNA targeting Renilla luciferase) and parental cells (Fig. 1D), supporting our hypothesis that menin engagement in this context was not responsible for the highly potent activity of MI-2 in glioma. Menin acts as an adaptor to recruit MLL1, an H3K4 methyltransferase, to chromatin (12, 15). Consistent with a largely menin–MLL-independent function of MI-2, we observed no significant difference in the quantity of H3K4me3 peptides by mass spectrometry after treatment of glioma cells with MI-2 above the IC50 concentration for DIPG-VI cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

Disruption of Cholesterol Homeostasis Underlies MI-2 Activity in Glioma.

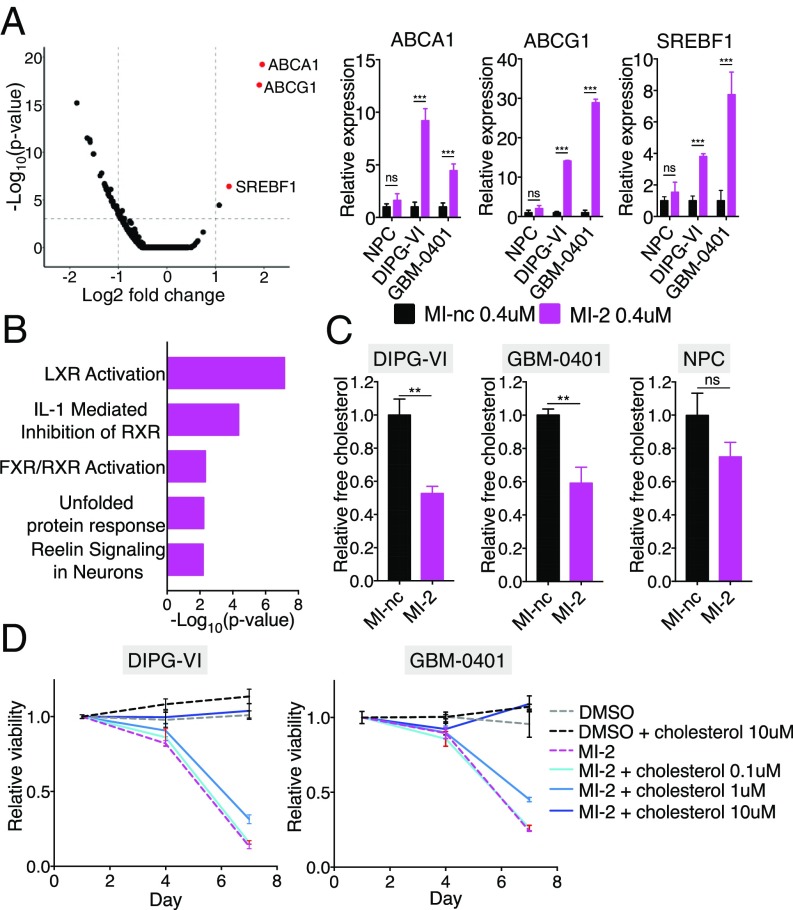

To characterize the mechanism of action of MI-2 in an unbiased fashion, we performed transcriptomic analysis of DIPG-VI cells treated for 48 h with MI-2 or its inactive analog MI-nc (7) (Fig. 2A). Unexpectedly, this analysis revealed significant changes in cholesterol homeostasis transcripts. Specifically, the most highly up-regulated transcripts were SREBF1 (steroid responsive binding factor 1), ABCG1 (ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 1), and ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1) (Fig. 2A). These genes are all canonical targets of LXR (liver X receptor), a transcription factor that promotes cholesterol export when activated by cholesterol metabolites or synthetic compounds (16). This finding was of particular interest in light of recent work implicating synthetic LXR agonists as therapeutic agents in glioma (17, 18). Notably, these transcriptional changes were consistently observed in both DIPG and adult glioma cell lines (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), and in contrast, NPCs, which were comparatively insensitive to MI-2, exhibited a diminished response. We performed an unbiased analysis of significantly up-regulated transcripts (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis; P < 0.05), which also identified LXR activation as the top enriched canonical pathway (Fig. 2B). To confirm this was a menin-independent transcriptional response, we treated MEN1 KO cells with MI-2 and observed robust up-regulation of LXR targets (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). In addition, we did not observe this transcriptional response after MI-503 treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C), further suggesting this response did not occur because of menin engagement.

Fig. 2.

(A, Left) Volcano plot of genome-wide RNA-Seq data, with cholesterol homeostasis transcripts highlighted in red. (A, Right) qPCR validation of most significant up-regulated transcripts in DIPG-VI, GBM-0401, and NPCs. (B) Ingenuity pathway analysis of significantly up-regulated genes (P < 0.05) in DIPG-VI cells treated with 0.4 μM MI-2 compared with 0.4 μM MI-nc (control). (C) Relative free cholesterol levels measured by LC-MS in cells treated with 0.4 μM MI-2 compared with 0.4 μM MI-nc (n = 3). (D) Relative cell viability of cells treated with MI-2 with/without addition of exogenous cholesterol (n = 4 per condition). ns, not significant; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Given the prominent LXR signature induced by MI-2 and the well-characterized function of LXR in promoting cholesterol export; we hypothesized that MI-2 would deplete cholesterol in glioma cells. Indeed, using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS), we observed significantly reduced free cholesterol in both DIPG-VI and GBM-0401 lines 48 h after MI-2 treatment (Fig. 2C). Importantly, provision of exogeneous cholesterol alone was sufficient to completely rescue cell death induced by MI-2 in both DIPG-VI and GBM-0401 cell lines, confirming cholesterol depletion was the dominant mechanism by which MI-2 was acting in this context (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). MI-2-induced cell death in MEN1 KO cells was also rescued by provision of exogenous cholesterol, strongly supporting the same mechanism of MI-2 activity in the presence and absence of menin (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Notably, we did not observe any rescue with MI-503-treated cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), further supporting a distinct mechanism of activity with MI-2.

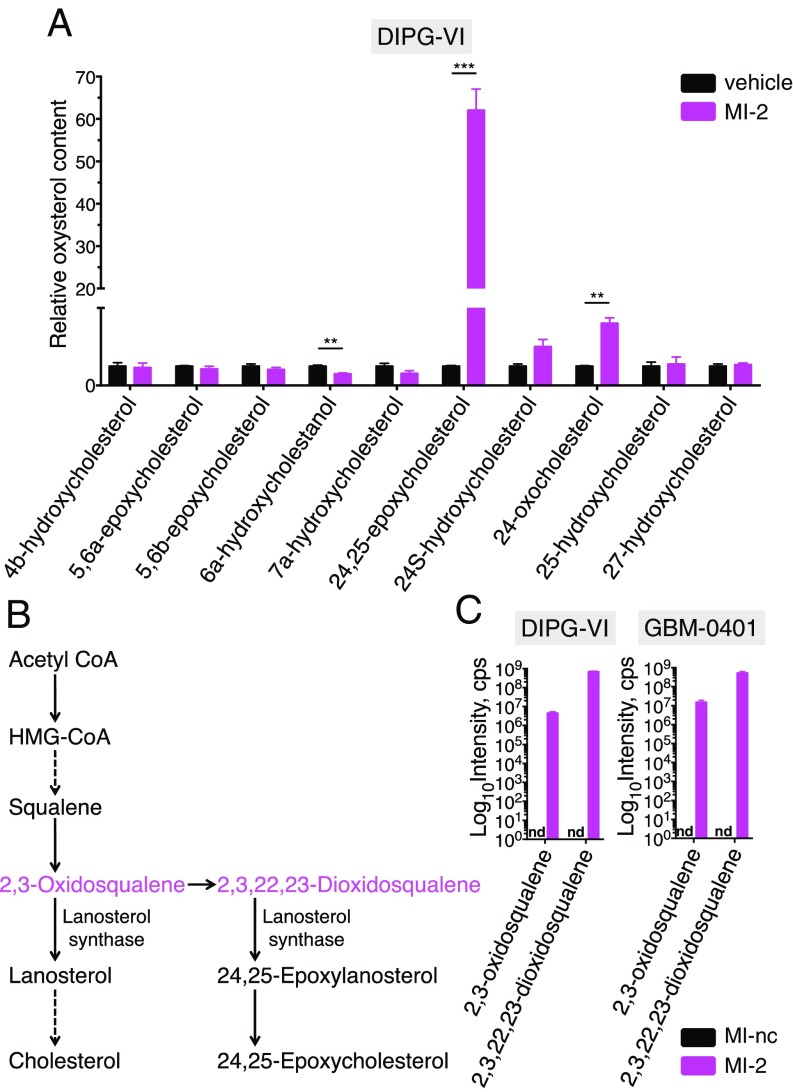

MI-2 Induces Prominent Accumulation of 24,25 Epoxycholesterol and Shunt Pathway Metabolites.

In the physiological regulation of cholesterol homeostasis, LXR is activated by binding of its natural ligands, which are oxysterols; oxidized products of cholesterol or cholesterol precursors that act to negatively regulate cholesterol levels (16, 19). To explore whether MI-2 promotes the generation or accumulation of oxysterols, we used LC-MS to measure a panel of oxysterols after 48 h of MI-2 treatment. Remarkably, we observed a striking and relatively selective elevation (up to 100-fold) in 24,25-epoxycholesterol levels (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). 24,25-epoxycholesterol is an oxysterol synthesized in a pathway parallel to cholesterol known as the shunt pathway (Fig. 3B), and is one of the most potent known endogenous LXR ligands (19, 20). Shunt pathway generation of 24,25-epoxycholesterol leads to cholesterol depletion via LXR-driven cholesterol export (19), but also via LXR-independent effects on cholesterol synthesis (21–23). To determine the extent to which LXR activation (by 24,25-epoxycholesterol) contributes to MI-2 induced cell death, we added an LXR antagonist (GSK-2033) (24) to MI-2-treated cells to block LXR activation, and were able to rescue cell death by ∼30%, consistent with a partially LXR-dependent mechanism of MI-2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Interestingly, we observed accumulation of 24,25-epoxycholesterol in NPCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), which were relatively insensitive to MI-2 (IC50 > 1.5 μM), suggesting the mechanism of resistance in this setting may be downstream of 24,25-epoxycholesterol generation. Consistent with this, NPCs showed decreased LXR activation (Fig. 2A) and less cholesterol depletion compared with DIPG and adult glioma cell-lines (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

(A) Relative levels of cellular oxysterol species as measured by LC-MS in DIPG-VI cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MI-2 for 48 h (n = 3). (B) Simplified schematic of cholesterol synthesis pathway and shunt pathway (dotted arrows denote multiple enzymatic steps). (C) Quantification of proximal shunt pathway species 2,3-oxidosqualene, and 2,3,22,23-dioxidosqualene by LC-MS after 48 h of treatment with 0.4 μM MI-nc (control) or MI-2 (n = 3). nd, not detected; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We reasoned that accumulation of 24,25-epoxycholesterol suggests MI-2 may be either inhibiting catabolism of this metabolite or increasing its generation by promoting shunt pathway activity. To explore which one of these mechanisms may be at play, we first determined whether more proximal shunt pathway metabolites were elevated (Fig. 3B). We measured levels of 2,3-oxidosqualene and 2,3,22,23-dioxidosqualene by LC-MS and found concomitant accumulation in the presence of MI-2 (Fig. 3C), confirming an increase in shunt pathway intermediates.

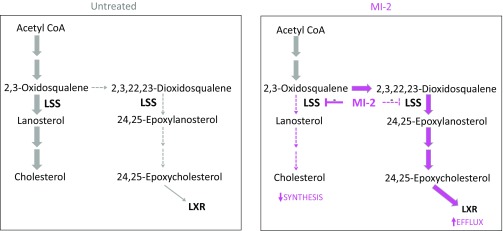

MI-2 Is a Direct Inhibitor of the Lanosterol Synthase.

Lanosterol synthase (LSS, also known as oxidosqualene cyclase) is a monotopic membrane protein that sits downstream of squalene in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 3B) and catalyzes the conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to lanosterol, the first sterol to be formed in the pathway (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) (25). LSS is also capable of catalyzing the conversion of 2,3,22,23-dioxidosqualene to 24,25-epoxylanosterol (Fig. 3B), and partial inhibition of LSS using small molecules disproportionately blocks conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to lanosterol, while permitting 24,25-epoxylanosterol synthesis, because of the increased affinity of LSS for 2,3,22,23-dioxidosqualene as a substrate (23, 26). Under these conditions, 2,3-oxidosqualene accumulates and is metabolized preferentially via the shunt pathway, eventually leading to 24,25-epoxycholesterol accumulation and LXR activation, with concurrent reduction of cholesterol synthesis resulting from decreased conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to cholesterol (23, 26).

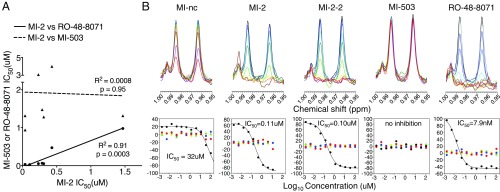

We were intrigued that MI-2-induced metabolite changes phenocopied those seen with partial LSS inhibition, so we tested the sensitivity of several DIPG and adult glioma cell lines to the LSS inhibitor, RO-48-8071 (27). We observed potent activity in our glioma lines (with NPCs being more resistant), mirroring our observations with MI-2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Indeed, there was a very strong correlation between MI-2 and LSS inhibitor sensitivity (RO-48-8071) in glioma cell lines (R2 = 0.91; P = 0.0003; Fig. 4A). We also found that RO-48-8071 induced up-regulation of LXR targets, and its effects on glioma cell viability could be rescued by exogenous cholesterol (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), consistent with a shared mechanism of action of RO-48-8071 and MI-2.

Fig. 4.

(A) Scatter-plot showing IC50 values for MI-2 from multiple glioma cell-lines (x-axis) vs. IC50 for either MI-503 or lanosterol synthase inhibitor (RO-48-8071), with linear regression shown. (B) NMR biochemical assay for enzymatic conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to lanosterol by human lanosterol synthase enzyme in the presence of increasing concentrations of MI-nc, MI-2, MI-2–2, MI-503, and RO-48-8071. (Upper) NMR spectra of solutions after reaction at different concentrations of inhibitors. A spectral region contains the NMR peaks originating from lanosterol (28-H at 0.985 ppm and 19-H at 0.963 ppm). Inhibitor concentrations were 0 (black), 0.0017 (blue), 0.005 (light blue), 0.015 (cyan), 0.046 (green), 0.137 (light green), 0.41 (yellow), 1.23 (pale yellow), 3.7 (orange), 11.1 (brown), 33.3 (magenta), and 100 (red) μM. (Lower) FA score vectors representing the dependence on inhibitor concentrations (representative replicate displayed). Those of factors with the five largest eigenvalues are shown (black, red, blue, green, and yellow for first to fifth, respectively).

Finally, to test whether lanosterol synthase was the direct enzymatic target of MI-2, we evaluated the ability of MI-2 to inhibit conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to lanosterol by lanosterol synthase in an in vitro biochemical NMR assay (28) (Fig. 4B). We observed potent inhibition of lanosterol synthase by MI-2 with an IC50 of 110 nM and, furthermore, MI-2-2 (the structural analog of MI-2, SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) also showed potent activity, with an IC50 of 100 nM. In contrast, we observed minimal activity with the inactive compound MI-nc, (IC50 of 32 μM), and no activity with the structurally distinct menin inhibitor, MI-503 (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

In this report, we characterize the mechanism of action of MI-2, a drug previously identified in a small molecule screen, as having a therapeutic effect in preclinical DIPG and glioma models. Elegant studies have demonstrated MI-2 is a menin inhibitor (7, 8), and in MLL-fusion leukemia cells, interruption of the menin–MLL interaction has a well-established mechanistic link to suppression of leukemia growth (7, 8, 12, 13, 29). In the context of glioma, however, although menin is expressed, our data show it is not a major target responsible for the antitumor effects observed after MI-2 treatment. Employing a genetic approach, we generated multiple menin knockout glioma cells and additionally demonstrated that these cells showed retained sensitivity to MI-2, pointing toward a distinct molecular target in this context. In further support of this conclusion, we showed that a more potent menin inhibitor exhibited relatively weak activity in glioma cells.

Using a combination of transcriptional, metabolomic, and biochemical analyses, we identify lanosterol synthase as the key molecular target that MI-2 directly inhibits to exert its effect in glioma, resulting in loss of cholesterol homeostasis and cell death (Fig. 5). Importantly, we confirm this activity is responsible for induction of cell death by complete rescue of the effect via provision of exogenous cholesterol. Notably, this potent activity is specific to MI-2 and not a characteristic of the newer-generation menin inhibitor, MI-503. Our work, and other recent studies (30, 31), underscore the importance of target deconvolution (32), the process of identifying the relevant molecular target of a small molecule, to reveal insights into the biology of a particular phenotype and provide a starting point for chemical optimization efforts and development of biomarker strategies (32).

Fig. 5.

Model showing effects of MI-2 on sterol synthesis. (Left) In the absence of MI-2, there is basal but low flux through the shunt pathway. (Right) MI-2 disproportionately inhibits the conversion of 2,3-oxidosqualene to lanosterol, and flux through the shunt pathway is increased, with concurrent decrease in flux from 2,3-oxidosqualene to cholesterol. Elevation of 24,25 epoxycholesterol contributes to cholesterol depletion by activation of LXR.

Metabolic reprogramming is now well-established as a hallmark of malignancy, which can generate therapeutic vulnerabilities (33, 34), and indeed, we observed MI-2 was more potent in glioma cells compared with normal neural progenitor cells. This was likely, in part, a result of a more dramatic up-regulation of LXR targets in glioma cells after MI-2 treatment compared with normal cells. Of note, normal neural progenitors robustly generated 24,25-epoxycholesterol after MI-2 treatment, suggesting there may be distinct transcriptional regulation of the LXR pathway in normal and glioma cells. Given MI-2 blocks lanosterol synthesis, we speculate that the activity of enzymes distal to lanosterol in the mevalonate pathway, which has been shown to vary greatly in distinct neural populations (35), may also contribute to the differential response to LSS inhibition between normal and glioma cells. In addition, the elevated cholesterol demand, to support increased cell proliferation and oncogenic signaling in malignant cells (36–38), may also be an important factor in the increased potency of MI-2 in glioma cells observed.

Alterations in cholesterol metabolism can result as a direct consequence of oncogenic mutations; for example, p53 mutations result in mevalonate pathway activation (39, 40), and mutations in tyrosine kinase receptors, such as epidermal growth receptor, promote increased capacity for cholesterol uptake (17). Both DIPG and adult gliomas harbor multiple mutations, and further work is needed to characterize how their effects interact to alter cholesterol metabolism. We speculate that cholesterol addiction may be a general feature of malignant gliomas, particularly important in the brain microenvironment, where cholesterol cannot be derived from the circulation because of the presence of the blood–brain barrier.

Our identification of lanosterol synthase as the target of MI-2 suggests modulating the activity of other enzymes (or regulatory proteins) in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway may have therapeutic utility in glioma. In support of this approach, a brain-penetrant LXR agonist showed impressive activity in preclinical glioma models (18), providing evidence that depleting cholesterol, even without directly affecting synthesis, may be effective. The most well-characterized enzyme in cholesterol metabolism is HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase), the target of statins, although there is some debate as to the efficacy of targeting HMGCR in preclinical glioma models (18, 41). It has been suggested that statins’ ability to deplete tumor cell cholesterol may be impaired by elevated low-density lipoprotein receptor expression on glioma cells (18) or homeostatic up-regulation of low-density lipoprotein receptor that follows statin treatment (42). This may be particularly relevant to glioma cells in the intracranial environment, where scavenging from astrocyte-produced cholesterol has been proposed to be a major source of cholesterol (18, 35, 43).

Cellular cholesterol levels are highly regulated, requiring the coordination of synthesis, efflux, and influx mechanisms that provide multiple potential avenues for intervention in glioma, which will require systematic evaluation. The antitumor efficacy when targeting different nodes within the cholesterol metabolic pathway may depend on the nature of feedback responses elicited and whether multiple processes are inhibited simultaneously (e.g., synthesis and transport). LSS as a therapeutic target is unique and potentially advantageous in this regard. Partial inhibition of LSS promotes flux through the shunt pathway, which results in the combinatorial effect of increasing 24,25 epoxycholesterol, which activates LXR-mediated cholesterol export while concurrently reducing postoxidosqualene cholesterol synthesis. This cholesterol depletion mechanism represents a double hit, and we speculate this may render compensatory mechanisms to maintain cholesterol by tumor cells less effective.

Materials and Methods

Complete details and descriptions of the materials used and methods for cell culture and proliferation assays; virus generation and cell transduction; CRISPR gene editing; metabolite quantification by LC-MS; NMR biochemical assays; quantitative PCR, RNA sequencing, and analysis; histone PTM quantification; and statistical analyses are provided in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the C.D.A. laboratory for their feedback regarding this work and Dr. Tarun Kapoor of Rockefeller University and Dr. David Russell of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for invaluable discussions regarding the project. We thank Mr. O. Tani of National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology for helpful advice regarding the NMR biochemical assay. We thank Dr. M. Monje of Stanford University and Dr. A. Carcabosa of Hospital Sant Joan De Deu for DIPG cell-lines used in this work. This work was made possible by funding from NIH Grant P01CA196539 (to C.D.A. and B.A.G.). V.T. is supported by National Cancer Institute Grant R01CA3865730 and Starr Cancer Consortium. J.G.M. is supported in part by NIH Grant HL20948. B.A.G. is supported by NIH Grants CA196539, GM110104 and a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Robert Arceci Scholar Award. R.E.P. is supported by the American Brain Tumor Association Basic Research Fellowship in honor of Bruce and Brian Jackson, Memorial Sloan Kettering Internal Diversity Enhancement Award, Cure Childhood Cancer, and the Cure Starts Now.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1820989116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012. Neuro-oncol. 2015;17:iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu G, et al. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nat Genet. 2012;44:251–253. doi: 10.1038/ng.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartzentruber J, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funato K, Major T, Lewis PW, Allis CD, Tabar V. Use of human embryonic stem cells to model pediatric gliomas with H3.3K27M histone mutation. Science. 2014;346:1529–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1253799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pathania M, et al. H3.3K27M cooperates with Trp53 loss and PDGFRA gain in mouse embryonic neural progenitor cells to induce invasive high-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:684–700.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammad F, et al. EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for H3K27M-mutant pediatric gliomas. Nat Med. 2017;23:483–492. doi: 10.1038/nm.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grembecka J, et al. Menin-MLL inhibitors reverse oncogenic activity of MLL fusion proteins in leukemia. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi A, et al. Structural insights into inhibition of the bivalent menin-MLL interaction by small molecules in leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:4461–4469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallo M, et al. MLL5 orchestrates a cancer self-renewal state by repressing the histone variant H3.3 and globally reorganizing chromatin. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:715–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lan X, et al. Fate mapping of human glioblastoma reveals an invariant stem cell hierarchy. Nature. 2017;549:227–232. doi: 10.1038/nature23666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoyama A, Cleary ML. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borkin D, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan CW, et al. TCGA Research Network The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, et al. The same pocket in menin binds both MLL and JUND but has opposite effects on transcription. Nature. 2012;482:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR α. Nature. 1996;383:728–731. doi: 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo D, et al. An LXR agonist promotes glioblastoma cell death through inhibition of an EGFR/AKT/SREBP-1/LDLR-dependent pathway. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:442–456. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villa GR, et al. An LXR-cholesterol axis creates a metabolic co-dependency for brain cancers. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehmann JM, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3137–3140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janowski BA, et al. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song B-L, DeBose-Boyd RA. Ubiquitination of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase in permeabilized cells mediated by cytosolic E1 and a putative membrane-bound ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28798–28806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor FR, et al. 24,25-Epoxysterol metabolism in cultured mammalian cells and repression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15039–15044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutaud O, Dolis D, Schuber F. Preferential cyclization of 2,3(S):22(S),23-dioxidosqualene by mammalian 2,3-oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188:898–904. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91140-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuercher WJ, et al. Discovery of tertiary sulfonamides as potent liver X receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3412–3416. doi: 10.1021/jm901797p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoma R, et al. Insight into steroid scaffold formation from the structure of human oxidosqualene cyclase. Nature. 2004;432:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature02993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe AH, et al. Enhanced synthesis of the oxysterol 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol in macrophages by inhibitors of 2,3-oxidosqualene:lanosterol cyclase: A novel mechanism for the attenuation of foam cell formation. Circ Res. 2003;93:717–725. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000097606.43659.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morand OH, et al. Ro 48-8.071, a new 2,3-oxidosqualene:lanosterol cyclase inhibitor lowering plasma cholesterol in hamsters, squirrel monkeys, and minipigs: Comparison to simvastatin. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:373–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tani O, et al. NMR biochemical assay for oxidosqualene cyclase: Evaluation of inhibitor activities on Trypanosoma cruzi and human enzymes. J Med Chem. 2018;61:5047–5053. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dafflon C, et al. Complementary activities of DOT1L and Menin inhibitors in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31:1269–1277. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohki Y, et al. Perturbation-based proteomic correlation profiling as a target deconvolution methodology. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;26:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klaeger S, et al. The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs. Science. 2017;358:eaan4368. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terstappen GC, Schlüpen C, Raggiaschi R, Gaviraghi G. Target deconvolution strategies in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:891–903. doi: 10.1038/nrd2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vander Heiden MG. Targeting cancer metabolism: A therapeutic window opens. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:671–684. doi: 10.1038/nrd3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: A cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nieweg K, Schaller H, Pfrieger FW. Marked differences in cholesterol synthesis between neurons and glial cells from postnatal rats. J Neurochem. 2009;109:125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabitova L, et al. Endogenous sterol metabolites regulate growth of EGFR/KRAS-dependent tumors via LXR. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1927–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho YK, Smith RG, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor activity in human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 1978;52:1099–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, Schulze A. Hooked on fat: The role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:1353–1363. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freed-Pastor WA, et al. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moon S-H, et al. p53 represses the mevalonate pathway to mediate tumor suppression. Cell. 2019;176:564–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, et al. MYC-regulated mevalonate metabolism maintains brain tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4947–4960. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuya Y, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptors play an important role in the inhibition of prostate cancer cell proliferation by statins. Prostate Int. 2016;4:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfrieger FW, Barres BA. Synaptic efficacy enhanced by glial cells in vitro. Science. 1997;277:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.