Abstract

Objectives

The study aimed to determine the extent to which latent trajectories of neck–shoulder pain (NSP) are associated with self-reported sick leave and work ability based on frequent repeated measures over 1 year in an occupational population.

Methods

This longitudinal study included 748 Danish workers (blue-collar, n=620; white collar, n=128). A questionnaire was administered to collect data on personal and occupational factors at baseline. Text messages were used for repeated measurements of NSP intensity (scale 0–10) over 1 year (14 waves in total). Simultaneously, self-reported sick leave (days/month) due to pain was assessed at 4-week intervals, while work ability (scale 0–10) was assessed using a single item (work ability index) at 12-week intervals over the year. Trajectories of NSP, distinguished by latent class growth analysis, were used as predictors of sick leave and work ability in generalised estimation equations with multiple adjustments.

Results

Sick leave increased and work ability decreased across all NSP trajectory classes (low, moderate, strong fluctuating and severe persistent pain intensity). In the adjusted model, the estimated number of days on sick leave was 1.5 days/month for severe persistent NSP compared with 0.1 days/month for low NSP (relative risk=13.8, 95% CI 6.7 to 28.5). Similarly, work ability decreased markedly for severe persistent NSP (OR=12.9, 95% CI 8.5 to 19.7; median 7.1) compared with low NSP (median 9.5).

Conclusion

Severe persistent NSP was associated with sick leave and poor work ability over 1 year among workers. Preventive strategies aiming at reducing severe persistent NSP among working populations are needed.

Keywords: chronic pain, LCGA, neck pain, occupational, pain trajectories

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study investigating the association of longitudinal trajectories of neck–shoulder pain with sick leave and work ability.

Repeated monthly assessments over 1 year allowed detailed analyses of the time course of pain intensity, sick leave and work ability.

High response rates were obtained during each month of follow-up.

Self-reported measurements of exposure and outcome during the same time-period are potential limitations.

Introduction

Neck–shoulder pain (NSP) is a common condition, with annual prevalence rates between 27% and 48% in different working populations.1 NSP is one of the leading causes of years lived with disability worldwide,2 and is associated with reduced work ability3 and high sick leave rates.4 5 In workers with NSP, 20% had at least one spell of sick leave in 1 year.4 Sick leave risks are higher in workers with more severe NSP intensity.6 The economic burden of NSP on organisations and society is considerable.7–9 The estimated total cost of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996 was US$686 million,7 and the estimated total cost of both neck and back pain in Sweden in 2001 was 1% of the gross national product.9

NSP is considered a heterogeneous condition ranging from very mild symptoms to severe chronic pain10 with a substantial individual variability in progression over time.11–13 This heterogeneity may, however, comprise homogeneous subpopulations with distinct patterns of pain, unique risk factors and different underlying pathophysiology.14 Revealing such subpopulations is likely important for early identification, establishing risk factors, and improving prevention and treatment.15 However, most existing studies have been conducted on patients with low back pain, for example,15–17 while studies identifying and describing the patterns of NSP in working populations with a wide range of pain severities are sparse. Also, there is a lack of research on the predictive value of NSP subpopulations; which is crucial for understanding the extent to which NSP subpopulations are of clinical and occupational relevance regarding intervention and treatment. Thus, it is important for research and occupational and clinical practice to distinguish subpopulations of workers with different trajectories of NSP (eg, severity, temporal variability and time course) while assessing their predictive value against core prognostic outcomes, such as sick leave and work ability.4 18 19

Work ability, as defined as the balance between human resources and work demands,20 is determined by multiple factors.21 The perception of poor work ability is associated with sick leave and early retirement.22 Sick leave due to pain is likely multifactorial, and several personal and work related (physical and psychosocial) factors have been identified as potential determinants of increased risks.4 19 23 24 High physical workload is associated with poor work ability and occurrence of sick leave due to pain,4 25 and may hamper return to work.23 Thus, the level of physical workload is a potential moderator of the relationship of NSP trajectories with work ability and sick leave.

Most previous studies on the prognosis of NSP have relied only on few measurements in time interspersed by long intervals, for example, years.11 26 Such studies are not designed to capture the detailed time course (trajectory) or temporal fluctuations in NSP (eg, between weeks or months). In contrast, frequent repeated measurements of pain facilitate accurate and precise identification of individual pain trajectories27 and minimise recall bias.28

Latent class growth analysis (LCGA) is a common statistical approach for identifying homogeneous sub-populations (latent classes) based on individual growth parameters (ie, intercept, slope and residual variance) in repeated measures data.29 We have previously used LCGA to distinguish trajectory classes of NSP among the current population of workers based on frequent repeated measurements of NSP over 1 year.30 We identified six distinct trajectories of NSP ranging from ‘asymptomatic’ (prevalence 11%) to ‘severe persistent NSP’ (9%). Several personal and occupational factors, as well as symptom characteristics at baseline predicted trajectory class membership. However, understanding the occupational and clinical relevance of trajectories of NSP requires a determination of their predictive value against core occupational and clinical outcomes. Particularly, identifying NSP trajectories associated with unfavourable outcomes would likely aid targeted prevention and treatment.

The aim of this study is to determine the extent to which latent trajectories of NSP are associated with self-reported sick leave due to musculoskeletal pain and with work ability based on frequent repeated measures over 1 year in an occupational population. A second aim is to investigate the temporal association (within person) between fluctuations in NSP and the outcomes sick leave and work ability.

Methods

Study design

This is a prospective study using data from the Danish physical activity cohort with objective measurements (DPhacto). The study protocol for the cohort is reported in detail elsewhere.31 Data collection took place from April 2012 to May 2014 at 15 Danish companies, including workers in four occupational sectors (cleaning, manufacturing, transportation and office work/administration). The initial contact and recruitment of companies were performed in collaboration with a large Danish union. The companies were selected to represent blue-collar occupations with different levels of physical demands at work.

Baseline data collection consisted of a brief web-based questionnaire, a standard health examination and objective diurnal measurements of physical activity and heart rate (presented elsewhere).32 33 Prospective self-reported data on musculoskeletal pain, sick leave due to pain and work ability was collected repeatedly over 12 months using text messages.

Study population

The inclusion criterion for participation was current employment within any of the recruited work places. Exclusion criteria were holding a managing position or being pregnant or a student/trainee. In addition, workers not responding to the baseline questionnaire and/or the prospective measurements were excluded.

Among the 2107 invited workers, 1119 agreed to participate and 32 of them were excluded due to holding a managing position (n=17) or being pregnant (n=2) or a student/trainee (n=13). Of the remaining 1087 eligible workers, 782 responded to the questionnaire and 748 took part in the prospective measurements from baseline. Thus, the final study sample consisted of 748 workers (blue-collar, n=620; white collar, n=128). Descriptive characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population (n=748)

| N | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 748 | 44.8 | 9.6 | ||

| Men N (%) | 411 (55) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 732 | 27.3 | 4.8 | ||

| Seniority (years) | 722 | 13.5 | 10.3 | ||

| Administration workers N (%) | 128 (17) | ||||

| Blue-collar workers N (%) | 620 (83) | ||||

| Cleaning | 115 (15) | ||||

| Manufacturing | 448 (60) | ||||

| Transportation | 57 (8) | ||||

| Physical work load at baseline (scale 1–10) | 723 | 5.3 | 2.4 | ||

| Sick leave days | |||||

| Baseline (days/month) | 741 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Last follow-up (days/month) | 655 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| Total days (over all time points) | 746 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.8 | 20.9 |

| Work ability (scale 0–10) | |||||

| Baseline | 646 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.5 | 2.0 |

| Last follow-up | 671 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.2 | 2.4 |

| Mean work ability (over all time points) | 732 | 8.8 | 2.5 | 8.3 | 1.7 |

| NSP intensity (scale 0–10) | |||||

| Baseline | 748 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| Last follow-up | 652 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Mean NSP intensity (over all time points) | 748 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| Number of pain regions at baseline (count) | 745 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Compliance to text messages (missing responses, count) | |||||

| NSP intensity | 748 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.7 |

| Sick leave | 746 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.6 |

| Work ability | 732 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

BMI, body mass index; NSP, neck–shoulder pain.

Repeated assessment using text messages

Text messages (SMS) were used to assess self-reported pain intensity in the neck–shoulder region, days on sick leave and work ability using the commercial software ‘SMS-Track’ (https://sms-track.com/). Starting at baseline, data on NSP and sick leave were collected at 4-week intervals (14 waves), while data on work ability were collected at 12-week intervals (four waves in total) during the 1-year study. The SMS were sent on Sundays, with a reminder the following day.

Neck–shoulder pain

Pain intensity in the neck–shoulder region (NSP) the past month was assessed using an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS), which ranges from 0 (‘no pain’) to 10 (‘worst pain imaginable’). The worker responded to the question ‘Rate the worst pain you have experienced in your neck/shoulders within the past month?’ The NRS is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing pain intensity34 and is recommended as an outcome in clinical trials.35

Sick leave

Sick-leave due to pain was assessed using a single-item from the validated Outcome Evaluation Questionnaire36: ‘Within the past month, how many days have you been absent from work due to pain in muscles or joints?’ with response categories ranging from 0 to 31 days. Based on a recent meta-analysis, self-reported sick leave demonstrates good test–retest reliability and reasonably high convergent validity against records.37

Work ability

Work ability was assessed using a validated single item22 from the work ability index.38 The worker responded to the question ‘Please rate your present work ability?’ with response categories ranging from 0 (unable to work) to 10 (‘work ability as its best’). A score ≤7 denotes poor work ability.39

Assessment of possible confounders and effect modifiers

Theoretical assumptions and empirical evidence were used to select possible confounders and effect modifiers which were accounted for in the statistical analyses. The following variables were measured at baseline as previously described30: age (years) and gender (male or female) based on civil registration number, body mass index (BMI) based on objectively measured height and weight, occupational sector (manufacturing, cleaning, transportation and administration/office work within the same workplaces) and seniority in the current job (years). Physical work load was measured by the question ‘How physically demanding do you normally consider your present work?’ using a 10-point (1–10) response scale modified from Borg,40 with higher values indicating higher physical demands. Multisite pain was measured based on the Standardised Nordic Questionnaire for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms41 asking about pain intensity (NRS, scale 0–10) during the past 3 months in seven different anatomical areas (ie, neck/shoulders, elbows, hands/wrists, lower back, hips, knees and feet/ankles). A cut-point of >2 was used to indicate the occurrence of pain, whereby the number of pain sites was determined.42 Since the relationship between NSP, sick leave and work ability may depend on the level of physical demands at work, physical work load was considered both a confounder and an effect modifier, while the other variables were solely included as possible confounders.

Statistical analyses

Growth trajectories (latent classes) of the intensity in NSP were identified using LCGA in Latent Gold V.5.1 (Statistical Innovations Belmont, MA, USA). The LCGA procedure and the resulting trajectory classes of NSP are described in a previous study on the same population.30 In brief, the LCGA assigns individuals to latent classes based on maximum posterior probabilities. That is, using growth parameters (ie, intercept, slope and residual variance) reflecting change in an observed variable (ie, pain intensity) over time, LCGA assigns individuals to latent classes (categorical variable) assuming homogeneity within class and heterogeneity between classes.29 43

The LCGA models were performed using Time (14 waves over 1 year) as a continuous linear predictor and NSP intensity as a continuous dependent variable. Missing values were considered as missing at random and included in all models without imputations. The optimal number of classes was determined based on appropriate model fit indices, that is, Bayesian information criterion (BIC), entropy and bootstrap log likelihood ratio (BLRT), which were obtained in consecutive LCGA models with 1–10 a priori class solutions. Then, the models were evaluated based on the estimated growth parameters and clinical distinction between the identified classes. The identified trajectories of NSP were used as an independent variable in further statistical analyses of associations with sick leave and work ability over the same year.

The association of NSP trajectories with sick leave (SMS at 4-week intervals over 1 year) and work ability (SMS each quarter) during the same year was determined using generalised estimation equation (GEE) models with an auto regressive first order covariance structure to account for weaker correlations with increasing distance between time points.

The association of NSP trajectories with sick-leave (days/month) was tested using GEE models with a Poisson distribution and a log link function. Fixed factors were NSP trajectory class (categorical variable), time (continuous variable, 14 time points) and the interaction between trajectory class and time. The interaction term was kept in the model if it was significant (p<0.05). We tested both linear and quadratic time trends, but decided on a linear model since the quadratic model did not improve model fit. The primary GEE models were constructed in three steps: (model 1) unadjusted, (model 2) adjusted for age, gender and BMI, and (model 3) additionally adjusted for occupational sector (four categories) and physical work load (continuous variable). Then, we tested if the results of the primary models were consistent when accounting for baseline pain intensity and comorbidity of multisite pain, as they may be associated with both NSP trajectories and the outcomes. Thus, secondary models were estimated with additional adjustment for the intensity of NSP (model 4) and the number of pain regions (model 5) at baseline (past 3 months). Finally, to test for potential effect modification by physical work load, model 3 was re-run with an interaction between NSP trajectory class and physical work load (model 6).

The association of NSP trajectory class with work ability (dependent variable, ordinal scale) was tested using GEE models with a multinomial distribution and a cumulative logit link function. Fixed factors were NSP trajectory class (categorical variable), time (linear continuous variable, four time points), and the interaction between trajectory class and time, which was kept only if reaching significance (p<0.05). The models were constructed with and without adjustment for covariates, as explained above.

Additional GEE models were constructed to investigate the within-person association of temporal fluctuations in the intensity of NSP with sick leave and work ability (outcomes). To partition the within and between subjects variances in the predictor (intensity of NSP), the mean pain intensity score across all time points was determined for each individual. Then, the person mean pain score was subtracted from each repeated pain rating and used as an independent variable (within subject effect), while adjusting for the person mean pain as a covariate (between subjects effect).43 Thus, these GEE models were constructed with three fixed factors: (1) time (14 waves), (2) the person mean pain intensity across waves and (3) the difference from the mean pain intensity during each wave for the individual (within subject effect). The within-subject effect would then reflect the population averaged association with the outcome for each unit change in pain intensity per month for the individual. Model specifications for sick leave and work ability were the same as above. The models were estimated with and without adjustment for potential confounders as explained above.

The GEE models were estimated using SPSS software V.22 (IBM, USA). For each model, we derived the exponential estimate, that is, relative risk (RR) and OR for sick leave and work ability, respectively, and 95% CIs. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were directly involved in setting the research questions and outcomes, design and conduct of this study, or interpretation of the results. Results will be disseminated to the participants at http://www.nfa.dk/.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1. The study sample consisted of both males and females, and most were blue-collar workers. The workers were on average of middle age, slightly overweight, and had been in their current job for 14 years. The mean intensity of NSP across all time points was 2.6 (scale 0–10). Most of the workers rated high work ability (>7, scale 0–10) across the study period, while the average worker accumulated 6 days on sick leave due to pain over 1 year, although with a considerable dispersion between individuals. Compliance to the repeated measurements (text messages) in the study was high; on average, the workers had 1.2 missing responses to pain and sick leave (14 waves) and 0.4 missing responses to work ability (four waves) (table 1). The amount of missing data increased over time. During the second wave, the response rates were 96%, 96% and 93% for pain, sick leave and work ability, respectively, while the response rates dropped to 87%, 88% and 90% during the last wave.

Identified latent trajectories of NSP

Based on model fit indices (BIC, entropy and BLRT) and distinction between classes obtained from consecutive LCGA models, a six-class solution was chosen.30 The growth pattern and prevalence (%) of the six identified trajectory classes of NSP were characterised as follows (see also online supplementary figure A): class 1, asymptomatic (11%); class 2, very low NSP (10%); class 3, low recovering NSP (18%); class 4, moderate fluctuating NSP (28%); class 5, strong fluctuating NSP (24%) and class 6, severe persistent NSP (9%). The trajectory classes with lower intensities of NSP (classes 1–3) did not differ in total days on sick leave or mean work ability over 1 year; and the occurrence of sick leave was very low, while work ability was high across the three classes. Thus, classes 1–3 were merged into a single category (low NSP 39%), which was used as a reference in further analyses.

bmjopen-2018-022006supp001.jpg (234.9KB, jpg)

Association between NSP trajectory classes and sick leave over 1 year

Estimates of the association of NSP trajectories with sick leave due to pain (days/month) are shown in table 2. There was no significant time effect on sick leave (unadjusted RR=1.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.06). Thus, the interaction between NSP trajectory class and time was discarded from the models.

Table 2.

Association of neck–shoulder pain (NSP) trajectory class with sick leave (days/month) and work ability (ordinal scale 0–10) over 1 year, referencing low NSP

| GEE models (classes) |

N | Sick leave | Work ability | ||||||

| P value | RR | 95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

P value | OR | 95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

||

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Low NSP | 292 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Moderate NSP | 208 | <0.001 | 3.28 | 1.89 | 5.68 | <0.001 | 2.45 | 1.87 | 3.21 |

| Strong NSP | 178 | <0.001 | 8.98 | 4.78 | 16.89 | <0.001 | 8.64 | 6.38 | 11.69 |

| Severe NSP | 70 | <0.001 | 17.64 | 9.36 | 33.23 | <0.001 | 15.07 | 9.94 | 22.85 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Low NSP | 286 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Moderate NSP | 204 | <0.001 | 3.25 | 1.87 | 5.64 | <0.001 | 2.40 | 1.83 | 3.16 |

| Strong NSP | 174 | <0.001 | 8.61 | 4.54 | 16.33 | <0.001 | 9.03 | 6.62 | 12.31 |

| Severe NSP | 68 | <0.001 | 16.00 | 8.17 | 31.34 | <0.001 | 14.77 | 9.63 | 22.66 |

| Model 3 | |||||||||

| Low NSP | 277 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Moderate NSP | 199 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 1.75 | 5.52 | <0.001 | 2.43 | 1.84 | 3.20 |

| Strong NSP | 165 | <0.001 | 7.58 | 3.91 | 14.71 | <0.001 | 8.12 | 5.91 | 11.16 |

| Severe NSP | 66 | <0.001 | 13.83 | 6.72 | 28.49 | <0.001 | 12.93 | 8.50 | 19.67 |

RR estimates, indicating the relative increase in the number of days on sick leave per month, were obtained using GEE with a Poisson distribution for days on sick-leave (measured at 4-week intervals). ORs indicating the likelihood of a 1-unit reduction in work ability, were obtained using GEE with a multinomial distribution for work ability (measured at 12-week intervals).

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender and body mass index.

Model 3: additionally, adjusted for occupational sector (four categories, referencing administration) and physical work load.

GEE, generalised estimation equation; RR, relative risk.

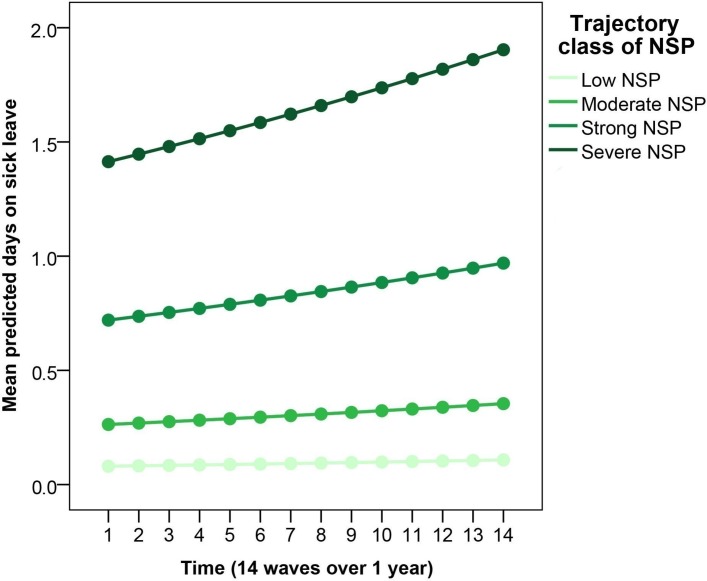

Based on the fully adjusted model (table 2, model 3) referencing low NSP, the RR of sick leave increased for moderate (RR=3.1, 95% CI 1.8 to 5.5), strong fluctuating (RR=7.6, 95% CI 3.9 to 14.7) and severe persistent NSP (RR=13.8, 95% CI 6.7 to 28.5). On average, the estimated number of days on sick leave per month was 0.1 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.15) for low NSP, 0.3 (95% CI 0.2 to 0.4) for moderate NSP, 0.8 (95% CI 0.5 to 1.2) for strong NSP, and 1.5 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.4) for severe persistent NSP. Predicted values of sick leave for each wave over 1 year are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean 1-year trajectories of days on sick leave obtained in the fully adjusted model in each trajectory class of neck–shoulder pain (NSP). The x-axis represents the 14 pain ratings over 1 year. The y-axis represents the mean predicted number of days on sick leave per month.

Additional adjustment for multisite pain showed similar estimates for moderate NSP (RR=3.0, 95% CI 1.7 to 5.4), strong fluctuating NSP (RR=7.2, 95% CI 3.5 to 14.5) and severe persistent NSP (RR=13.1, 95% CI 6.1 to 28). Also, adjustment for baseline pain intensity revealed stronger estimates for moderate NSP (RR=3.7, 95% CI 2.1 to 6.8), strong fluctuating NSP (RR=10.9, 95% CI 5.1 to 23.7) and severe persistent NSP (RR=24.5, 95% CI 10.4 to 57.9), although with wider CIs.

There was no significant interaction between NSP trajectory class and physical work load on sick leave.

Association between NSP trajectory classes and work ability over 1 year

Estimates of the association between trajectories of NSP and work ability (measured each quarter) are shown in table 2.

There was a small time effect indicating reduced work ability over the year (unadjusted OR=1.05, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.11). There was no interaction between NSP trajectory class and time, whereby this interaction was discarded from the model.

NSP trajectory class was inversely associated with work ability (table 2). Based on the fully adjusted model referencing low NSP (table 2, model 3), the likelihood of a 1-unit reduction in work ability increased for moderate (OR=2.4, 95% CI 1.8 to 3.2), strong fluctuating (OR=8.1, 95% CI 5.9 to 11.2), and severe persistent NSP (OR=12.9, 95% CI 8.5 to 19.7). The median scores (IQR) of work ability during the year were 9.5 (1.7) for low NSP, 9.0 (2.0) for moderate NSP, 7.8 (2.0) for strong NSP and 7.1 (2.5) for severe persistent NSP.

Additional adjustment for multisite pain showed slightly weaker estimates for moderate NSP (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.7 to 2.9), strong fluctuating NSP (OR=6.4, 95% CI 4.6 to 9.0) and severe persistent NSP (OR=10.4, 95% CI 6.7 to 16.0). Further, adjustment for baseline pain intensity showed similar estimates for moderate NSP (OR=2.6, 95% CI 1.9 to 3.5), strong fluctuating NSP (OR=9.1, 95% CI 6.3 to 13.1) and severe persistent NSP (OR=15.4, 95% CI 9.3 to 25.5).

There was no significant interaction between NSP trajectory class and physical work load on work ability.

Within-person association of NSP with sick leave and workability

Due to the high work ability scores and low prevalence of sick leave in the classes with lower intensities of NSP, these analyses included only workers assigned to the trajectory classes strong fluctuating and severe persistent NSP (n=248).

The within-person associations of pain intensity with sick leave due to pain and work ability are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Within-person effect of temporal fluctuations in neck-shoulder pain intensity (scale 0–10) on sick leave (days/month) and work ability (scale 0–10) over 1 year

| GEE models | N | Sick leave | Work ability | ||||||

| P value | RR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Model 1 | 248 | 0.008 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.005 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.19 |

| Model 2 | 242 | 0.008 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.009 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.19 |

| Model 3 | 231 | 0.011 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 0.002 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 1.21 |

RR estimates, indicating the relative increase in the number of days on sick leave per month, were obtained using GEE with a Poisson distribution for days on sick-leave (measured at 4-week intervals). ORs indicating the likelihood of a 1-unit reduction in work ability, were obtained using GEE with a multinomial distribution for work ability (measured at 12-week intervals). Estimates indicate the within-person effect of change in pain intensity on change in sick leave and work ability per month.

Model 1: adjusted for the person mean pain intensity across time points.

Model 2: additionally, adjusted for age, gender and body mass index.

Model 3: additionally adjusted for occupational sector and physical work load.

GEE, generalised estimation equation; RR, relative risk.

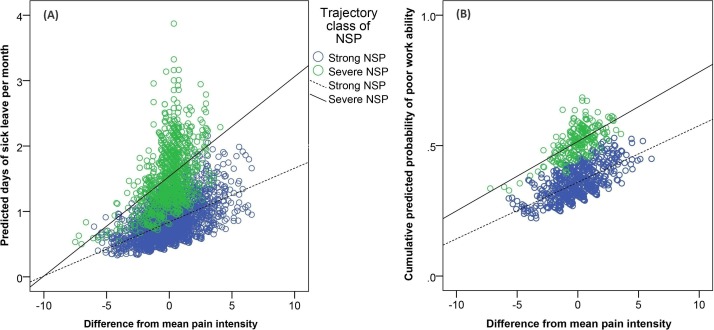

Within-person fluctuations in the intensity of NSP were positively associated with sick leave (adjusted RR=1.11, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.21). That is, higher intensity of NSP was associated with more days of sick leave during a particular month at the individual level (table 3 and figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Association between temporal fluctuations in neck–shoulder pain (NSP) intensity and the outcomes sick leave and work ability. The x-axis represents the difference in pain intensity scores from the person mean pain intensity across time points. The y-axis represents the predicted number of days on sick leave per month (A) and the predicted cumulative probability of poor work ability (B), as defined by the cut-point ≤7 (scale 0–10).39

A similar within-person association was found between fluctuations in pain intensity and work ability (adjusted OR=1.13, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.21). For example, increasing intensity of NSP was associated with higher probabilities of reduced work ability (table 3). This association is illustrated in figure 2B as the estimated probability of reporting poor work ability (≤7 on the 0–10 scale).39

Discussion

In summary, this prospective study investigated the relationship between LCGA-based trajectories of NSP and the outcomes sick leave and work ability. We found that the distinguished trajectory classes of NSP were strongly associated with sick leave due to pain and poor work ability over 1 year, and that the temporal fluctuations in pain intensity predicted sick leave and work ability at the individual level.

To our knowledge, this study is unique in assessing the association between LCGA-based trajectories of NSP and important prognostic outcomes among workers. A clear strength of the study is the use of frequent prospective measures of both exposure (intensity of NSP) and outcomes (work ability and sick leave) over 1 year. The high response rate to the SMS is also a strength supporting the feasibility of this method to obtain frequent repeated measurements of pain in future studies on the prognosis of NSP.

Trajectories of NSP, sick leave and work ability

The trajectory classes of NSP used in this study were distinguished using LCGA, resulting in six distinct trajectories of NSP.30 This corroborates a study by Lövgren et al (2014) which used Growth Mixture Modelling to identify six trajectory classes of NSP in nursing students entering working life. In contrast, the severity of NSP in the current sample of workers was much higher, perhaps due to the large proportion of blue-collar workers in this study.1 The high prevalence of strong fluctuating (24%) and severe persistent NSP (9%), with mean pain intensities of 5 and 7 (scale 0–10), respectively, is noteworthy.

Trajectory class of NSP was strongly associated with the number of days on sick leave over the 1-year study period. Particularly, the fully adjusted model indicated an increased RR of sick leave in the trajectory class with severe persistent NSP (mean 1.5 days/month), compared with low NSP (mean 0.1 days/month). This result is in line with previous prospective studies showing a positive association between NSP intensity and sick leave.4 6 This result persisted with adjustment for potential confounding by multisite pain, which was associated with NSP and sick leave in previous studies.19 44 45 Thus, severe persistent NSP appears to be strongly associated with sick leave due to musculoskeletal pain, regardless of multisite pain and other personal and occupational factors.

The four trajectory classes of NSP were also associated with poor work ability over the year (table 2). For instance, the probability of reporting reduced work ability was 13 times higher for the trajectory class with severe persistent NSP (median work ability 7.1 on the 0–10 scale), compared with low NSP (median work ability 9.5), regardless of inclusion of potential confounders in the model (table 2, model 3). In agreement, previous studies have found that intense NSP is associated with reduced work ability in workers,3 46 although none of these examined pain trajectories. Interestingly, including baseline intensity of NSP (ie, past 3 months) as an additional covariate in model 3 did not reduce the estimated association for sick leave or work ability. In fact, this adjustment resulted in even stronger estimates for work ability, which clearly indicates that the LCGA-based trajectory classes of NSP have a predictive value beyond that explained by past pain intensity assessed at a single time point.

The observed consistent associations between the identified trajectories of NSP and the outcomes sick leave and work ability support the prognostic value of LCGA-based trajectories of NSP among workers, and suggests that such sub-populations can be of clinical and occupational relevance. Thus, this study supports using LCGA to identify distinct sub-populations of workers with different patterns of NSP. Further, the increased risk of sick leave and poor work ability for severe persistent NSP points to the need for interventions and preventive strategies aiming at reducing severe persistent NSP in working populations.

Effect modification by physical work load

High physical work load is a known risk factor for incident NSP and has been associated with a poor prognosis.47 Thus, the association for NSP trajectories with sick leave and work ability was expected to be modified by the level of self-reported physical work load at baseline. However, we could not confirm any interaction between trajectory class of NSP and physical work load neither for sick leave nor work ability. Still, it is possible that more precise technical measurements of physical work exposure would have yielded different results.

Association of temporal fluctuations in NSP with sick leave and work ability

NSP is often referred to as a recurrent and fluctuating condition.11 However, the temporal fluctuations in NSP have rarely been investigated in detail, and few, if any, studies have examined whether fluctuations in NSP are associated with sick leave and work ability. The frequent repeated measures allowed us to assess the within-person temporal association between fluctuations in the intensity of NSP and sick leave (every fourth week) and work ability (every 12th week). We found that the within-person fluctuations in pain intensity were significantly associated with both sick leave and work ability, which persisted in the fully adjusted model (table 3). That is, when the individual pain score increased, the likelihood of sick leave and poor work ability also increased. Thus, not only could we address the differences between workers in temporal patterns of NSP, but also whether the temporal fluctuations in NSP at the individual level are of predictive value.

Methodological discussion

As this study is limited to self-reported measures of pain and the outcomes sick leave and work ability, one cannot overlook the possibility of bias. Regarding self-reported sick leave, meta-analytic evidence indicates reasonably high convergent validity against organisation and register-based records, although with a slight tendency for under-reporting.37 Thus, there is a risk for underestimation of sick leave in this study. The question about days on sick leave the past month did not distinguish between work days and non-work days, which may have resulted in less precise estimates. Also, although both outcomes sick leave and work ability were assessed prospectively over 1 year, the NSP trajectories were determined during the same time period and thus causal inferences should be made with caution. Still, it seems most likely that pain preceded the occurrence of sick leave, rather than the reverse relationship. The compliance to text messages was very high on average (table 1). Still, missing data increased slightly over time, which might have introduced some uncertainties in the models.

We addressed several relevant factors as confounders or effect modifiers (physical work load) of the association of pain trajectories with sick leave and work ability. However, as the causes of sick leave and poor work ability are likely multifactorial,4 19 21 the focus on pain trajectories as predictors is a potential limitation because it does not inform about other potentially important prognostic factors. Also, the possibility of residual confounding by non-measured factors cannot be ruled out. For instance, we did not measure comorbidity of chronic conditions that might be associated with both NSP trajectories and the outcomes.

Since this study was conducted in a non-random sample with a predominance of blue-collar workers, it is important to verify the study findings in other working populations. The general notion of NSP as a fluctuating and reoccurring condition11 is corroborated by our data, but this is rarely taken into account in observational studies on NSP. The inclusion of residual variance in the LCGA model allowed us to distinguish trajectory classes with more or less fluctuating patterns of NSP. Temporal fluctuations were more prominent in the NSP trajectories with moderate and strong pain, which may have contributed to the lower risk of sick leave and poor work ability compared with the trajectory class with severe persistent NSP.

Since the trajectories with lower intensities of NSP, that is, including asymptomatic, very low NSP and low recovering NSP, did not differ regarding their low occurrence of sick leave and poor work ability, we decided to merge them into a single reference category in the prediction models. Still, it is possible that these three classes differ in other prognostic outcomes.

Conclusion

This longitudinal study shows that severe persistent NSP is associated with sick leave due to pain and reduced work ability over 1 year among workers. The high prevalence of severe persistent NSP and the increased risk of sick leave and poor work ability point to the need for preventive strategies aiming at reducing severe persistent NSP among workers. Overall, our findings contribute with further understanding of the possible consequences of different time patterns and levels of NSP, which can be of general importance for researchers, practitioners and clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DMH contributed to the statistical data analyses and drafting of the manuscript. AH and MBJ contributed to the conception, design, data collection and funding of the full DPHACTO study. All authors (DMH, AH, SD-L, MBJ and CDNR) contributed to the conception of this study, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the Danish Government (Satspulje) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte Dnr. 2009–1761).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, and evaluated by the Regional Ethics Committee in Copenhagen, Denmark (H-2-2012-011).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed on request by e-mail (aho@arbejdsmiljoforskning.dk).

Patient consent for publication: All participants provided their written informed consent prior to participation.

References

- 1. Côté P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32:S70–S86. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rashid M, Kristofferzon ML, Heiden M, et al. Factors related to work ability and well-being among women on sick leave due to long-term pain in the neck/shoulders and/or back: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:672 10.1186/s12889-018-5580-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holtermann A, Hansen JV, Burr H, et al. Prognostic factors for long-term sickness absence among employees with neck-shoulder and low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:34–41. 10.5271/sjweh.2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burdorf A, Naaktgeboren B, Post W. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal sickness absence and return to work among welders and metal workers. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:490–5. 10.1136/oem.55.7.490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersen LL, Clausen T, Burr H, et al. Threshold of musculoskeletal pain intensity for increased risk of long-term sickness absence among female healthcare workers in eldercare. PLoS One 2012;7:e41287 10.1371/journal.pone.0041287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borghouts JA, Koes BW, Vondeling H, et al. Cost-of-illness of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996. Pain 1999;80:629–36. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00268-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woodhouse A, Pape K, Romundstad PR, et al. Health care contact following a new incident neck or low back pain episode in the general population; the HUNT study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:81 10.1186/s12913-016-1326-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansson EK, Hansson TH. The costs for persons sick-listed more than one month because of low back or neck problems. A two-year prospective study of Swedish patients. Eur Spine J 2005;14:337–45. 10.1007/s00586-004-0731-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fejer R, Jordan A, Hartvigsen J. Categorising the severity of neck pain: establishment of cut-points for use in clinical and epidemiological research. Pain 2005;119:176–82. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, et al. Course and Prognostic Factors for Neck Pain in Workers. European Spine Journal 2008;17:93–100. 10.1007/s00586-008-0629-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruls VE, Bastiaenen CH, de Bie RA. Prognostic factors of complaints of arm, neck, and/or shoulder: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain 2015;156:765–88. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, et al. The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Pain 2004;112:267–73. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lövgren M, Gustavsson P, Melin B, et al. Neck/shoulder and back pain in new graduate nurses: A growth mixture modeling analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:625–39. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kongsted A, Kent P, Axen I, et al. What have we learned from ten years of trajectory research in low back pain? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:220 10.1186/s12891-016-1071-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Axén I, Leboeuf-Yde C. Trajectories of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013;27:601–12. 10.1016/j.berh.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dunn KM, Campbell P, Jordan KP. Long-term trajectories of back pain: cohort study with 7-year follow-up. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003838 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Vries HJ, Reneman MF, Groothoff JW, et al. Workers who stay at work despite chronic nonspecific musculoskeletal pain: do they differ from workers with sick leave? J Occup Rehabil 2012;22:489–502. 10.1007/s10926-012-9360-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feleus A, Miedema HS, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Sick leave in workers with arm, neck and/or shoulder complaints; defining occurrence and discriminative trajectories over a 2-year time period. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:114–22. 10.1136/oemed-2016-103624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ilmarinen J, von Bonsdorff M, Ability W. The encyclopedia of adulthood and aging, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21. van den Berg TI, Elders LA, de Zwart BC, et al. The effects of work-related and individual factors on the Work Ability Index: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:211–20. 10.1136/oem.2008.039883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahlstrom L, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M, et al. The work ability index and single-item question: associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health–a prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:404–12. 10.5271/sjweh.2917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lötters F, Burdorf A. Prognostic factors for duration of sickness absence due to musculoskeletal disorders. Clin J Pain 2006;22:212–21. 10.1097/01.ajp.0000154047.30155.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karels CH, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhagen AP, et al. Sickness absence in patients with arm, neck and shoulder complaints presenting in physical therapy practice: 6 months follow-up. Man Ther 2010;15:476–81. 10.1016/j.math.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ariëns GA, Bongers PM, Hoogendoorn WE, et al. High physical and psychosocial load at work and sickness absence due to neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2002;28:222–31. 10.5271/sjweh.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walton DM, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, et al. An Overview of Systematic Reviews on Prognostic Factors in Neck Pain: Results from the International Collaboration on Neck Pain (ICON) Project. Open Orthop J 2013;7:494–505. 10.2174/1874325001307010494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Axén I, Bergström G, Bodin L. Using few and scattered time points for analysis of a variable course of pain can be misleading: an example using weekly text message data. Spine J 2014;14:1454–9. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miranda H, Gold JE, Gore R, et al. Recall of prior musculoskeletal pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:294–9. 10.5271/sjweh.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An Introduction to Latent Class Growth Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2008;2:302–17. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hallman DM, Rasmussen CDN, Jørgensen MB, et al. Time course of neck-shoulder pain among workers: A longitudinal latent class growth analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2018;44:47–57. 10.5271/sjweh.3690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jørgensen MB, Korshøj M, Lagersted-Olsen J, et al. Physical activities at work and risk of musculoskeletal pain and its consequences: protocol for a study with objective field measures among blue-collar workers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hallman DM, Birk Jørgensen M, Holtermann A. On the health paradox of occupational and leisure-time physical activity using objective measurements: Effects on autonomic imbalance. PLoS One 2017;12:e0177042 10.1371/journal.pone.0177042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hallman DM, Gupta N, Heiden M, et al. Is prolonged sitting at work associated with the time course of neck-shoulder pain? A prospective study in Danish blue-collar workers. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012689 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011;152:2399–404. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113:9–19. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keefe FJ, Linton SJ, Lefebvre JC. The outcome evaluation questionnaire: description and initial findings. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy 1992;21:19–33. 10.1080/16506079209455886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johns G, Miraglia M. The reliability, validity, and accuracy of self-reported absenteeism from work: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol 2015;20:1–14. 10.1037/a0037754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, et al. Work ability index. Helsinki: Finnish institute of occupational health, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neupane S, Miranda H, Virtanen P, et al. Multi-site pain and work ability among an industrial population. Occup Med 2011;61:563–9. 10.1093/occmed/kqr130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Borg G. Borg’s percieved exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon 1987;18:233–7. 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neupane S, Leino-Arjas P, Nygård CH, et al. Developmental pathways of multisite musculoskeletal pain: what is the influence of physical and psychosocial working conditions? Occup Environ Med 2017;74:468–75. 10.1136/oemed-2016-103892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoffman L, Stawski RS. Persons as contexts: evaluating between-person and within-person effects in longitudinal analysis. Res Hum Dev 2009;6:97–120. 10.1080/15427600902911189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sarquis LM, Coggon D, Ntani G, et al. Classification of neck/shoulder pain in epidemiological research: a comparison of personal and occupational characteristics, disability, and prognosis among 12,195 workers from 18 countries. Pain 2016;157:1028–36. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haukka E, Kaila-Kangas L, Ojajärvi A, et al. Pain in multiple sites and sickness absence trajectories: a prospective study among Finns. Pain 2013;154:306–12. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bugajska J, Sagan A. Chronic musculoskeletal disorders as risk factors for reduced work ability in younger and ageing workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2014;20:607–15. 10.1080/10803548.2014.11077069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mayer J, Kraus T, Ochsmann E. Longitudinal evidence for the association between work-related physical exposures and neck and/or shoulder complaints: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2012;85:587–603. 10.1007/s00420-011-0701-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022006supp001.jpg (234.9KB, jpg)