Abstract

Objective

To explore patient involvement in the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines and associated interventions.

Design

Scoping review.

Methods

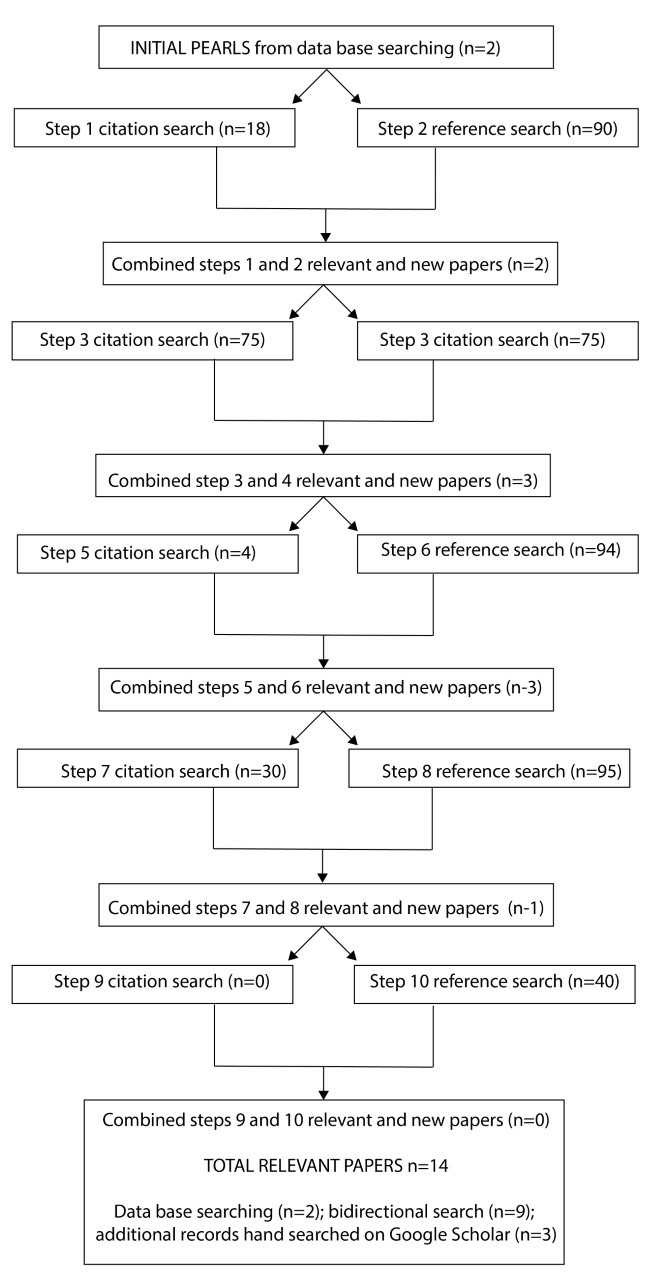

A methodological framework was followed to identify recent publications on patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines and interventions. Initially, relevant databases were searched to identify pertinent publications (published 2013–2018). Reflecting the scarcity of included studies from these databases, a bidirectional citation chasing approach was used as a second search step. The reference list and citations of all identified papers from databases were searched to generate a full list of relevant references. A grey literature search of Google Scholar was also conducted.

Results

From an identified 2078 papers, 14 papers were included in this review. Our findings provide insights into the need for a fundamental change to IPC, from being solely the healthcare professionals (HCPs) responsibility to one that involves a collaborative relationship between HCPs and patients. This change should be underpinned by a clear understanding of patient roles, potential levels of patient involvement in IPC and strategies to overcome barriers to patient involvement focusing on the professional–patient relationship (eg, patient encouragement through multimodal educational strategies and efforts to disperse professional’s power).

Conclusions

There is limited evidence regarding the best strategies to promote patient involvement in the implementation of IPC interventions and guidelines. The findings of this review endorse the need for targeted strategies to overcome the lack of role clarity of patients in IPC and the power imbalances between patients and HCPs.

Keywords: health policy, clinical governance, quality in health care, risk management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used rigorous scoping review methods, including a detailed search of multiple databases (with peer-reviewed literature), grey literature that complied with standards for the conducting and reporting of reviews, and a bidirectional citation chasing approach was used as a supplementary search step.

Our research adopted an integrative approach to provide an overview of what is known and what the trending topics are in empirical and grey literature about patient involvement in the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines and interventions.

Identification of gaps in the knowledge about how to operationalise a fundamental change to IPC, from being solely the healthcare professionals (HCPs) responsibility to one that involves a collaborative relationship between HCPs and patients.

The quality of evidence, that is, part of systematic reviews, was not assessed in this review as in other scoping reviews.

A lack of standardised language around some key terms could mean some studies were not identified and papers were limited to hospital settings.

Background

Healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) represent a major risk to patient safety and significantly contribute to increased morbidity, higher mortality rates, prolonged hospitalisations, long-term disability and increased resistance to antimicrobials, resulting in a substantial financial burden on health services.1 HCAIs are the most frequent complication for patients receiving healthcare, with pooled prevalence rates of 7.6% in high-income countries and 10.1% in middle to low-income countries.1 Despite the high incidence rates, it is estimated that 30%–70% of all HCAIs are preventable.2 The failure to adhere consistently to infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines is a key factor in maintaining the high rates of HCAI occurrence, with healthcare professionals (HCPs) average compliance rates with hand hygiene guidelines standing at just 38.7%.3

Many authors stress the need to increase patient involvement in IPC implementation in healthcare settings and when developing new guidelines and initiatives.4–7 It is believed that this will ensure a more patient-centred service that prioritises their needs8 and increases patient safety by empowering them to take control of their own IPC and increases compliance of HCPs with guidelines.9 10

Even when patients are aware of their potential contribution to IPC, their involvement can be undermined by an apprehension about asking or getting involved.11 12 Several publications suggest that patients can feel that it is not their responsibility to ask about IPC. They can also perceive that HCPs have enough expertise to recognise the importance of standard procedures in HCAI prevention without having to raise the subject.13 14

Current studies on HCAI have provided valuable insights on how to overcome existing barriers to patient involvement.6 15 16 However, few of them have mapped the existing strategies to involve patients in the implementation of HCAI guidelines and IPC initiatives across different healthcare settings that go beyond the hand hygiene compliance context. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to describe the strategies that have been employed to foster patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines and associated interventions.

Methods

Study design

To identify publications in both peer-reviewed and grey literature, and provide a broad overview of strategies to support patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines, a scoping review was undertaken. The ‘scoping’ approach helps to generate an overall map of the evidence that has been produced, to clarify working definitions underpinning a research area and/or the conceptual boundaries of a topic.17 Therefore, scoping reviews differ from systematic reviews which focus on the effectiveness of a particular intervention based on predetermined outcomes. However, scoping reviews can also be systematic and follow methodological frameworks, such as the one provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute17, which is internationally recognised.

The research question that oriented this scoping review was: What are the existing strategies or interventions to support patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines and associated interventions?

Inclusion criteria and types of sources

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in table 1. Search limit included a 5-year date restriction (2013–2018).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Published in English, Portuguese, Spanish or French. Articles in peer-reviewed journals. |

Papers were excluded if they reported on HCAI guideline recommendations, simply cited the importance of service-user involvement, or reported on broad experiences of HCAI guideline implementation. |

Report of evidence focused on:

|

Search strategy and database search

The search terms were generated based on consideration of the ‘participants’ (health service users and informal carer for a service user), the ‘concept’ under investigation (patient involvement in interventions and clinical guidelines) and the ‘context’ (HCAI and IPC).

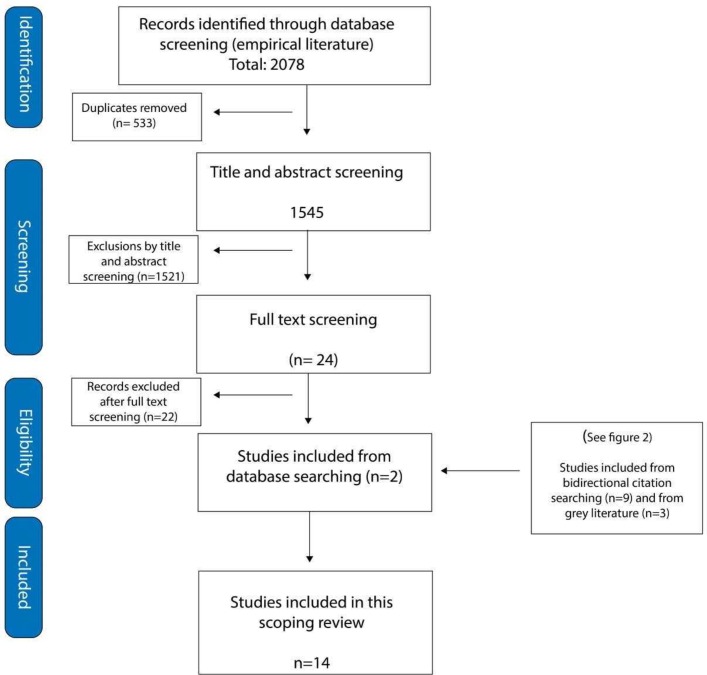

Bidirectional citation chasing

We used a bidirectional citation chasing or pearl growing approach to generate a full list of references pertaining to patient engagement with IPC guideline implementation (figure 1). The pearls in this instance were the two papers sourced in the database search18 19 and through the citation chasing process, nine new papers were identified.5–7 9–11 20–22

Figure 1.

Bidirectional citation searching structure and results.

Grey literature

Following a search of the grey literature on Google Scholar using the terms ‘patient involvement’23 or ‘guidelines’24 or ‘HCAI’ 25, 207 articles were screened from a total of 21 pages reviewed. However, of the 12 that merited inclusion for data extraction, only three were new papers26–28 (figures 1 and 2). The searches for peer-reviewed literature and grey literature were initially undertaken in March and April 2018 and updated in July 2018. A detailed definition of participants, concept and context alongside their respective search terms are described in table 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart of identification and inclusion of studies. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 2.

Definition of participants, concept and context and their respective search terms

| Participants | Concept | Context |

| Patients and family members: Health service users included patient, family, and those who care (informal carer) for a service user. | Patient involvement in interventions and clinical guidelines: Patient and family involvement refers to ‘activity that is done ‘with’ or ‘by’ patients or members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them’.23 Guidelines refer to ‘systematically developed evidence-based statements which assist providers, recipients and other stakeholders to make informed decisions about appropriate health interventions’.24 |

Healthcare associated infection (HCAI) and infection prevention and control (IPC): HCAI refers to ‘an infection occurring in a patient during the process of care in a hospital or other healthcare facility which was not present or incubating at the time of admission’.25 IPC refers to ‘a scientific approach and practical solution designed to prevent harm caused by infection to patients and health workers’.25 |

| Search terms: Patient OR client OR ‘family member’ OR relative |

Search terms: (Implement* OR introd* OR uptake OR utilis* OR utiliz* OR complian* OR concord* OR adhere* OR disseminat* OR adopt* OR translat* OR appl* OR ‘diffusion of innovation’ OR barrier* OR facilitator* Or enabler*) AND guideline* |

Search terms: (Infection N3 (healthcare OR ‘health care’ OR health care OR hospital OR nosocomial Or resistant OR antibiotic OR control OR prevention)) OR (pathogen N3 (healthcare OR ‘health care’ OR health care OR hospital OR nosocomial OR resistant OR antibiotic OR control OR prevention)) OR ‘Alert organism*’ OR ‘cross infection’ OR cross-infection’ OR ‘HAI’ OR HCAI’ OR ‘Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus’ OR ‘MRSA’ OR ‘M.R.S.A.’ OR ‘Clostridium difficile’ OR ‘C. difficile’ OR C. difficile’ OR ‘C. diff’ OR ‘C. diff’ OR ‘multidrug resistant organisms’ OR ‘MDRO’ OR ‘M.D.R.O.’) |

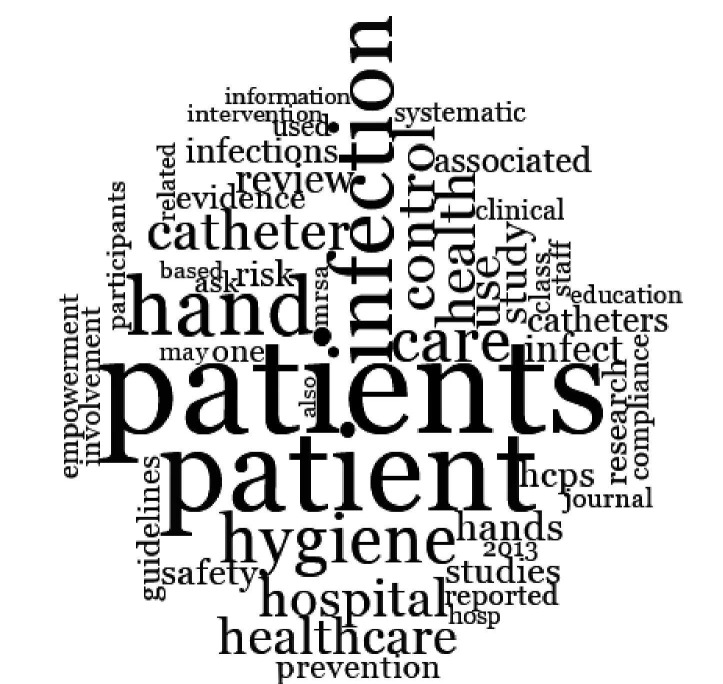

The summary of our search processes, screening and data analysis is available as an online supplementary file. As part of our data analysis, a word cloud was developed to aid the identification of trending topics in the literature (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Word cloud (‘Wordle’) generated in NVivo based on 14 papers selected for scoping review of patient involvement in infection prevention and control guidelines.

bmjopen-2018-025824supp001.pdf (204.4KB, pdf)

Empirical data from the literature were extracted by HA and a sample was subsequently cross-checked by JH to ensure consistency. This process was repeated for the grey literature. Full details of data extraction can be seen in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Data extraction table. Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Country | Study aims | Study design | Study participants healthcare professional (HCP):including nurses, doctors, and allied health P: patient and caregivers, family |

Key findings | Sample size |

| Hill et al 19 | USA | Assess patient (P) and healthcare professional (HCP) perspectives on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): a qualitative assessment of knowledge, beliefs, and behaviour, with an ultimate goal of developing patient educational materials that address the issues unique to SCI/D. | Cross-sectional observational design and focus groups. | HCP: physicians and nurses P: eight veterans with |

HCP and P identified gaps in general MRSA knowledge, gaps in knowledge of good hand hygiene practices and of required frequency of hand hygiene and barriers to educating P with SCI/D during inpatient stays. Recommendation: Development of ‘easy-to-understand message delivered in a consistent and engaging manner that also provided the patient with a clear way to meaningfully engage with their providers about MRSA prevention behaviours’ (p.89). | Thirty-three HCP and eight P. |

| McGuckin and Govednik6 | USA | To review the current literature on patient willingness to be empowered, barriers to empowerment and hand hygiene programmes that include patient empowerment and hand hygiene improvement. | Literature review | HCP: not specified other professions beyond medicine and nursing P: mention to patient and family member’s involvement. |

‘There is ongoing support from patients that they are willing to be empowered. There is a need to develop programmes that empower both healthcare workers and patients so that they become more comfortable in their roles’ (p.191). | Two studies: WHO HH guidelines and a companion review, ‘Patient Empowerment and Multimodal Hand Hygiene Promotion: a WineWin Strategy’. |

| See et al 28 | USA | Explore the attitudes and preferences of patients on haemodialysis regarding educating and engaging such patients in BSI prevention. | Focus groups, with patient ambassadors from Dialysis Patient Citizens. | P: patient ambassadors from Dialysis Patient Citizens. | Patients reported that education on infection prevention should begin early in the process of dialysis and that patients should be actively engaged as partners in infection prevention. | Twelve P |

| Loveday et al 27 | UK | To review and update the evidence base for making infection prevention control and recommendations. | Systematic review | HCP (not specified), P | Importance of patients and carers’s education about hand hygiene and their role in maintaining standards of healthcare workers’ hand hygiene. | 68 studies |

| Wyer et al 22 | Australia | Explore patients’ perspectives on infection prevention and control (IPC). | Video-reflexive ethnography | P | ‘Viewing and discussing video footage of clinical care enabled patients to become articulate about infection risks, and to identify their own roles in reducing transmission. The reflexive process engendered closer scrutiny and a more critical attitude to infection control that increased patients' sense of agency’ (p.1). | 14 P |

| Seale et al 21 | Australia | Examine the level of awareness towards patient empowerment, previous experiences with campaigns, and degree of acceptance toward the introduction of a new empowerment programme focused on engaging patients around infection control strategies. | Semistructured interviews | P | ‘Just over half of the participants were highly willing to assist with infection control strategies. Participants were significantly more likely to be willing to ask a doctor or nurse a factual question then a challenging question’ (p.447). ‘Patients are not receiving sufficient information about HCAIs and infection control, and they are not being encouraged to take a role’ (p.452). |

60 P |

| Davis et al 11 | UK | Systematic review of the effectiveness of strategies to encourage patients to remind HCPs about their hand hygiene. | Scoping review | HCP (not specified, but most studies involving nurses and physicians), P | The strategies (videos, videos and leaflet) showed promise in helping to increase patients’ intentions and/or involvement in reminding HCPs about their HH. | 28 studies |

| Seale et al 7 | Australia | Examine the level of awareness towards patient empowerment, previous experiences with campaigns and degree of acceptance towards the introduction of a new empowerment programme focused on engaging patients around infection control strategies. | Semistructured interviews | HCP (nurses, doctors and allied health staff). | Patient engagement remains an underused method. By extending the concept of patient empowerment to a range of infection prevention opportunities, the positive impact of this intervention will not only extend to the patient but to the system itself. | 29 HCP |

| Miller et al 26 | Australia | Identifying and integrating patient and caregiver perspectives for clinical practice guidelines on the screening and management of infectious micro-organisms in haemodialysis units. | Facilitated workshop | P (patients and family members). | Integrating patient and caregiver perspectives can help to improve the relevance of guidelines to enhance quality of care, patient experiences, and health and psychosocial outcomes. | 11 P (8 patients and 3 family members). |

| Tartari et al 18 | Netherlands | Identify basic and pragmatic recommendations for patients to be empowered by healthcare workers to seek information at an early stage and actively engage through their surgical journey. | Expert panel | HCP (not specified) | Nine pragmatic recommendations for the involvement of surgical patient in IPC are presented here, including a practice brief in the form of a patient information leaflet. | Five key IPC experts and infectious disease specialists, with a special interest in surgical site infections formed the expert panel. |

| Cheng et al 20 | China | Report a patient empowerment programme in hand hygiene promotion. | Quasi-experimental | HCP (nurses, doctors, and allied health staff) P |

‘A positive response from the healthcare workers was reported in 70 (93.3%) of 75 patients who reminded healthcare workers to clean hands as part of the empowerment programme. A significant increase in volume of alcohol-based handrub consumption was observed during the intervention period compared with baseline’ (p 562). | 167 P 114 HCP |

| Dadich and Wyer5 | Australia | Examine patient involvement in healthcare-associated infection (HAI) research. | Lexical review | HCP (not specified), P | ‘Patient involvement is largely limited to recruitment to HAI studies rather than extended to patient involvement in research design, implementation, analysis, and/or dissemination’. (p.1). | 148 studies |

| Alzyood et al 9 | UK | To provide an understanding from the perspective of HCPs on patient involvement in improving hand hygiene compliance of clinical staff. | Integrative review | HCP (nurses, doctors, and allied health staff), P | ‘Patient involvement was related to how patients asked and how HCPs responded to being asked. Simple messages promoting patient involvement may lead to complex reactions in both patients and HCPs. It is unclear, yet how patients and staff react to such messages in clinical practice’ (p.1329). | 19 papers |

| Butenko et al

10 |

Australia | To determine the best evidence available in relation to the experiences of the patient partnering with HCPs for hand hygiene compliance. | Systematic review | HCP (medical and nursing staff), P | ‘Organisational structures enable partnering between HCPs and patients do not fully support this partnership. Patients have different level of knowledge and balance partnering in HH against possible detrimental impacts on the caring relationship provided by HCP’ (p.1646). | Three papers |

BSI, bloodstream infections; HH, hand dygiene; SCI/D, spinal cord injury and disorders.

Table 4.

Data extraction table. Themes from analysis

| Reference | Patient role (vulnerable) | Patient role (responsible) | Patient role (expert) | Patient role (observer) | Passive level of patient involvement | Active level of patient involvement | Barriers on healthcare provider (HCP) and patients relationships |

| Hill et al 19 | x | x | x | Repetition or asking the patient to repeat back in their own words or demonstrates that they have absorbed the information. | Encouraged patients to actively engage with their provider by asking about their methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus status. Hand hygiene checklist which requires the patient to demonstrate their hand hygiene technique to a nurse. |

Patient can have fear of a negative response from their HCP. Perception that caregivers already know (or should know) when to perform hand hygiene. The belief that asking about hand hygiene is not part of the patient’s role. Feeling of embarrassment or awkwardness associated with asking about hand hygiene. |

|

| McGuckin and Govednik6 | x | x | Printed matter, oral demonstrations, audiovisual means. | Visual reminders to encourage patients to ask HCP. Set of strategies for developing a culture of shared responsibility to support patient involvement. |

Fear of reprisals was the most frequent reason to do not ask HCP about IPC. | ||

| See et al 28 | x | x | Print materials, DVDs, support groups and classes. | Partner with patients in infection control activities (eg, patients performing audits of infection control practices) Patient educating other patients about their experiences on infection prevention. This is facilitated by the oral culture of dialysis clinics (eg, with patients talking in the lobby). |

Patients can feel uncomfortable speaking to their providers. | ||

| Loveday et al 27 | x | x | Ensure patients, relatives and carers are given information regarding the reason for the catheter and the plan for review and removal. | ||||

| Wyer et al 22 | x | x | Viewing and discussing video footage of clinical care (involving patients and HCP). | Lack of conversation between patients and clinicians about IPC, and patients being ignored or contradicted when challenging perceived suboptimal practice. | |||

| Seale et al 21 | x | x | x | Use of messages to encourage patients to ask questions about HCAIs, preventing infections, how to HH, signs and symptoms of infection, wound care. | |||

| Davis et al 11 | x | x | HCP encouragement of both lay and expert patients to question their HH. | ‘Patients reported that HCP laughed at them, became angry or ignored their request to clean their hands’ (p.158). | |||

| Seale et al 7 | x | x | x | ‘Adhering to what they have been told to do’ (eg, maintaining general hygiene and HH, not sharing items with other patients)’ (p.265). | Informing staff if their wounds had become red or inflamed, using personal protective equipment, reporting issues with cleanliness) and prompting staff about their HH practices. | HCPs feel a lack of support, busy workloads, and negative attitudes as key barriers to the implementation of any empowerment/involvement programmes. | |

| Miller et al 26 | x | x | x | x | Workshop with patients to get their expertise in the development of guidelines. | ‘Patients and caregivers were concerned that disclosing information may impact on the care they receive from health professionals’ (p.218). | |

| Tartari et al 18 | x | x | x | Leaflet with information on preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative activities for the prevention of surgical site infections (SSIs). | Leaflet stating pragmatic recommendations to promote the participatory role of patients in IPC and encouraging patients to speak up. Encouraging an educational environment that stimulates patients to participate in their surgical care, inviting and allowing time for questions and clarifications on the information provided. |

HCPs support and encouragement is crucial for successful patient involvement activities surrounding SSI prevention. | |

| Cheng et al 20 | x | x | x | Patient was educated by ICNs for 10–15 min on the following: importance of hand hygiene during hospitalisation. | Patients are encouraged to remind HCPs to perform hand hygiene. Patients shy to ask are provided with a 4-inch printed visual aid with ‘Did You Clean Your Hands?’ | HCP expressed fear of conflicts between them and patients introduced by the empowerment programme. | |

| Dadich and Wyer5 | x | x | Suggest video reflexive ethnography and citizen social science as collaborative methodologies to improve practices by harnessing the expertise of individuals traditionally deemed as research subjects like patients and members of the public. | ||||

| Alzyood et al 9 | x | x | Video and leaflets to encourage patient involvement in safety-related behaviours. | Strategies to enable patients to speak up (eg, ‘It’s OK to Ask’ campaign, Thanks for Washing’ script and badges ‘Ask me if I’ve washed my hands’). | The active role of patients to speak up is challenging to both patients and staff. Staff feeling discomfort and distress if prompted to perform hand hygiene by patients. |

||

| Butenko et al

10 |

x | x | x | Organisation enablers for patient involvement in infection prevention and control (IPC): equipment, sinks, information sheets, educational videos. | Patients have reluctance to partner due to a perceived lack of knowledge and fear of retribution from HCP. Behaviours of HCP and prevailing culture did not support HH interventions partnering with patients. |

DVD, digital video disc; ICN, infection control nurses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in this research.

Findings

Characteristics of studies

Country of origin

The country of origin for primary authors was Australia (n=6), USA (n=3) and UK (n=3). The remaining studies were from China and Netherlands (both n=1).

Study participants

The studies explored both patients’ and healthcare providers’ roles in preventing and controlling HCAIs.

Type of studies

Fourteen papers from the international literature search were reviewed (table 3), six5 6 9–11 of which were literature reviews (eg, systematic, lexical and integrative), six studies7 19 21–26 28 that used qualitative approaches (eg, individual interviews and focus groups), one quasi-experimental study20 and an expert panel report.18

Trending topics

Combined word frequencies in all included papers indicate that: patient(s) 2.61%, infection(s) 1.13%, hand(s) 1.14%, hygiene 0.64%, catheter(s) 0.79%, control 0.52%, hospital 0.47%, prevention 0.27%, empowerment 0.21%, involvement 0.21% were the trending topics in studies of patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines and associated interventions (figure 3).

One of the most common words used in the included papers was ‘hands’. Appropriate hand hygiene of HCPs is regarded as the single most effective way to protect patients against HCAI and reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistant bacteria.3 In our study, all selected papers discussed hand hygiene compliance or had a specific focus on it.6 9 11 19 20 However, the implementation of IPC guidelines is not limited to hand hygiene compliance.

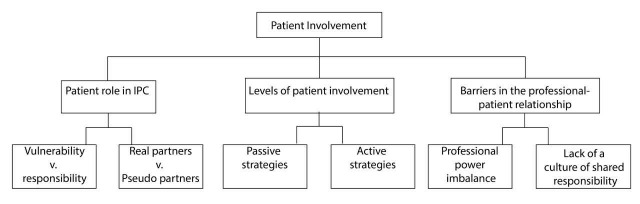

Thematic analysis

The results of thematic analysis revealed three themes pertaining to patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines: (1) Patients’ roles in IPC interventions; (2) Levels of patient involvement and (3) Barriers in the professional–patient relationship (figure 4). Patient involvement varied from being real partners to pseudopartners.

Figure 4.

Thematic map highlighting the overarching theme (patient involvement in the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines and associated interventions) and subthemes of analysis.

Patient role in IPC

There is a consensus in the studies that both patients and HCPs should jointly advocate for a culture of patient involvement in reducing the burden of HCAIs. However, the extent to which patients should be involved and their role in IPC interventions are not clearly defined. In general, patients can play different roles: potential transmitters of infections, active/passive supporters of IPC, to full partners in IPC. Some tensions emerge from these different roles, such as vulnerability versus responsibility and real partners versus pseudopartners.

Vulnerability versus responsibility

Concerns have been raised that involving patients in IPC interventions could increase patient anxiety and place responsibility on an already vulnerable person.11 Indeed, patients can feel initially shocked, confused and anxious when diagnosed with an infectious micro-organism. They also do not want to feel guilty and responsible for the transmission of infection to others.26 Vulnerability versus responsibility in infection transmission is the first tension regarding patient involvement in IPC.

Raising patient’s self-awareness on the risks of contamination and cross-transmission of micro-organisms is one of the methods of promoting patient involvement in IPC.27 However, our findings suggest that patients are more often acknowledged in their vulnerable role than viewed as potential players in the prevention of infection transmission. Transmission of HCAI through the contamination of patients’ hands, for example, is as important as contamination of HCP’s hands.11 However, the majority of studies have been focused only on strategies to encourage patients to ask HCPs about their compliance with standard precautions,5–7 9 11 18 20 21 undermining the development of a patient’s own accountability for IPC. Only three studies were identified that reported strategies to encourage patients to monitor themselves in IPC22 26 28; for example, with patient-to-patient education. A common characteristic between these three studies was the involvement of long-term care patients. Patients in dialysis clinics,28 for example, can be seen as more likely to be engaged in meaningful partnerships on IPC than those admitted for shorter stays. The oral culture of dialysis clinics (eg, with patients talking in the lobby) facilitates the exchange of knowledge on IPC between patients and enables them to monitor themselves by sharing stories of their own experiences of the consequences of suboptimal dialysis catheter care.28

Real partners versus pseudopartners

The second tension we identified rests in the dual role of patients in IPC interventions was real partners versus pseudo partners in IPC. This tension could partially be explained by the motivations behind patient involvement. On the one hand, patients are encouraged to get involved in IPC interventions to ensure that their perspectives and knowledge are taken into account to promote safe-care6; on the other hand, the rationale for involving patients in IPC interventions is to enable continuous monitoring of HCP practices without the need for additional staff or resources.11 On the partnership continuum, patients can be seen both as: (1) coresponsible partners with HCPs for patient safety and part of the solution, through the monitoring of both HCP’s behaviours and their own towards IPC or as (2) pseudopartners with an outsider perspective which involves observing what is happening, possibly reporting but not being seen as a true partner in IPC.

In spite of the reported willingness of patients to get involved as real partners in IPC,6 9 10 21 our findings revealed that patients can feel more comfortable playing a supportive role (monitoring HCP’s behaviours) rather than assisting with infection control strategies.21 However, the patient role can be undermined by a patient’s assumption that it is not their responsibility to ask about IPC behaviours9 and by patients assuming that HCPs know the importance of standard precautions.10 11 19 Our findings highlight patient reservations, embarrassments and fears associated with asking HCPs about IPC2 6 7 10 19 20 22 26 or impeding their role as partners equally responsible for IPC. When considering partnering for IPC, patients reported different levels of comfort associated with the perceived level of authority and the HCP’s role; for example, some patients reported feeling more comfortable asking a nurse about ICP rather than a physician.10 Hence, patients may require explicit permission by professionals to share with them the responsibility for IPC.6

Although some HCPs report they would be happy for a patient to remind them to wash their hands, they also admit that such conversations could be detrimental to the professional–patient relationship.9 Professionals may not support patients asking them about IPC, believing it will create conflict by implying a judgemental perspective and a lack of trust in HCPs to deliver safe care.7 11 Given the diversity of hospital patients and their capacities to be involved, for example, on the basis of severity of illness and cultural background, attempts to involve patients are not always perceived as appropriate. In some cultures, patient reminders can be considered an unacceptable source of confrontation.29 Likewise, asking patients to remind HCPs to cleanse hands can be seen as a behaviour contrary to the social norms that occur in healthcare settings.30 The relationship between the patient and HCP in the context of IPC reflects existing challenges in the whole organisation of care including power imbalances and clinical dominance that can impact negatively on HCP and patient partnerships.7 21

Building partnerships and collaborative relationships in healthcare requires a core component of role clarity. Our findings suggest a lack of clarity about the role of patients in IPC. This lack of role clarity results in tensions which can impact on the way patient involvement strategies are designed and delivered.

Levels of patient involvement

To encourage patients to partner with HCPs and be equally responsible for IPC, patient involvement interventions have been developed. Most of these strategies are aimed at empowering patients in IPC.7 20 22 26 McGuckin and Govednik6 argue that one cannot participate, be involved or be engaged without the components of empowerment including knowledge, skills and an accepting environment. Strategies for involving patients in IPC can vary in terms of topic areas covered and levels of patient participation; these range from relatively passive strategies to active participation in IPC.

Passive strategies, such as written information and audiovisual teaching, were described as potential tools to minimise risk of infection and promote patient engagement with IPC.27 In these strategies, patients and relatives were provided with information on IPC recommendations, such as hand hygiene and other standard precautions.5–7 11 18–20 31 Although important, these initiatives are criticised9 as they tend to limit patient involvement to adhering to what they are told to do rather than promoting patients as real partners for IPC.

Active strategies promote patient involvement beyond the development of patient’s knowledge and skills for IPC taking into account the patient’s beliefs and experiences.9 19 Taking patient beliefs into account can help to ensure that patients and HCPs have the same expectations. If patients believe that infection transmission cannot be prevented, they might assume that an active patient role would not help in the prevention of the spread of infection.11 When acknowledged in an active role, patients can provide additional insights into the development of IPC guidelines5 and become educators themselves.7 Some examples of active strategies are video reflexive sessions,22 patient-to-patient education, encouraging patients to monitor their own care26 and demonstrations followed by discussions on IPC.22

Both passive and active strategies require institutional prompts and staff training on how to communicate effectively with patients.6 7 9 HCP preparedness and institutional support are essential to promote a shift in how patient involvement is understood, that is, from a personal challenge regarding the care provided by an HCP to an organisationally supported mechanism for enhancing patient safety.9 This organisational shift can be facilitated by combined strategies of patient empowerment, education and encouragement.18 However, the professional–patient relationship and its intrinsic power imbalances remain as the main challenge to real professional–patient partnerships in IPC.9 22

Barriers in the professional–patient relationship

Our findings revealed that both professionals and patients could feel uncomfortable sharing the responsibility to control and prevent HCAIs. Patients’ intentions to better understand and engage in IPC may be negatively misinterpreted by HCPs. The degree of involvement and participation of patients in IPC is linked to both the extent to which they feel comfortable questioning authority and the quality of the relationship.

Two main barriers were described as: (1) relationship power imbalance and (2) lack of an organisational culture of shared responsibility. These are evidenced by a lack of conversation between patients and HCPs about IPC, as well as patients being ignored or contradicted when challenging perceived suboptimal practice.22 To overcome such barriers, some initiatives are described in the literature as dispersion of a professional’s power and developing a culture of shared responsibility.

To disperse a professional’s power, it is recommended that HCPs explicitly invite patients to engage with staff members and to remind them of their IPC duties.8 28 Effective communication between patients and HCPs is highlighted as a key aspect to address power imbalances. Seale et al 7 note that communication with patients on issues around IPC should be initiated at the earliest possible opportunity. Training programmes are recommended to enable HCPs to communicate with patients and be more responsive to patient concerns without taking offence.32 These training programmes and communication strategies can serve the function of addressing the power imbalance and HCP’s perception of control over to patients, thus creating a more collaborative partnership.6 7 Second, the literature reports some successful strategies for developing a culture of shared responsibility to support patient involvement.

Multimodal approaches for IPC, comprising patient education and encouragement by HCPs, are part of a culture of shared responsibility in IPC.9 11 18 20 21 These multimodal programmes are included in what McGuckin and Govednik6 describe as a key strategy for changing the culture around hand hygiene compliance. Alongside multimodal programmes, the authors describe key steps to patient involvement in the implementation of IPC interventions, these include: a review of the patient’s and HCP’s willingness to be involved; identification of potential role models to assist in improving the culture of shared responsibility for improving IPC; constant evaluation of barriers and facilitators to patients’ and HCP’s involvement at the institutional level and; to ensure key decision makers address such barriers.

Butenko et al 10 endorse the necessity for changes in cultural beliefs and behaviours to fully support patient involvement in IPC. They state that, although organisational structures to enable partnering between HCPs and patients for hand hygiene compliance exist, the prevailing culture can act as an impediment to the successful implementation of IPC interventions.

Discussion

Patient empowerment is based on the principles of shared responsibility and the building of partnerships between HCPs and patients. Establishing partnerships and collaborative relationships require a core component of role clarity. Our findings suggest that the role of the patient in IPC remains unclear and the existing efforts to involve them vary from passive to active strategies. Furthermore, these strategies are challenged by culturally engrained barriers in professional–patient relationships, such as power imbalances and clinical dominance.

In optimal real patient involvement, the process of clinical dominance is weakened, and HCPs are encouraged to relinquish their need to control their patients and the spread of HCAI by themselves. Instead, HCPs respect the patient’s central role in provision of care and encourage and support them to take responsibility for themselves and others in the context of IPC. One example of this real patient involvement is the use of video for reflexive sessions in which patients are given the opportunity to comment freely on videoed clinical care interactions and feedback their insights to HCP who care for them.33

Analysis of the professional–patient relationship shows the professional power issues enunciated in the literature.34 Reeves et al 35 noted that, even when developments appear to shift attention towards the patient and their family, there is continuous need to consider the nature of a patients ‘role within health and social professions in which ‘the balance of power between patients and professionals has traditionally favoured the latter’ (p.42). The twinned concept of power/knowledge is often discussed in the literature, advocating the need to increase patient understanding of their own health and care.34

Foucault examined the links between knowledge and power and discussed that professionals tend to use their knowledge as a way to control the ‘body’ of the patient.36 Empowering citizens is essential to give them knowledge of their bodies and health conditions and to be able to make decisions in a citizen’s action,37 which implies patients acting in their role as advocates on their own behalf and being responsible for keeping themselves healthy. Therefore, providing patients with knowledge of IPC, including information about and rationale for standard IPC recommendations, is a means of ensuring their active role, advocacy and responsibility in preventing HCAIs.

However, there is also a need to create an accepting environment for patient involvement in IPC. This would require changes to the predominant organisational culture in which professionals tend to control their organisation’s destinies38 and also play an authoritarian role over patients. The required cultural changes imply a reversion in the paternalist relation between HCPs and patients, as described by Parsons.39 It suggests a need to put patients in a responsible and protagonist role as experts in their own care and IPC, rather than being passive participants and observers of HCPs’ behaviours.

Conclusion

This review included 14 papers describing interventions available to support patient involvement in the implementation of IPC guidelines and associated interventions. Our findings endorse the need for patient involvement in IPC and provide insights into a fundamental change to IPC as a common responsibility for both patients and HCPs. This change should be supported by a clear understanding of patient roles, potential levels of patient involvement in IPC and strategies to overcome barriers in the professional–patient relationship (eg, patient encouragement through strategies to promote cultural change and efforts to disperse HCPs’ power).

Further studies are needed to understand how to develop and sustain an ‘accepting culture’ in which patient involvement is not a personal challenge to the care provided by HCPs, but as an essential part of patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Health and Health Research Board, Ireland for funding this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: HA, MM, SC, AB, CNB, DO, DG, ES, FB, JD, MPS, SC, SH, SM, TW and JH made substantial contributions to conception and design or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. HA, MM, SC, AB, ES, SC, SH and JH were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. HA, MM, SC, AB, CNB, DO, DG, ES, FB, JD, MPS, SC, SH, SM, TW and JH have given final approval of the version to be published. HA, MM, SC, AB, CNB, DO, DG, ES, FB, JD, MPS, SC, SH, SM, TW and JH have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: Funding for this study was supported by the Department of Health and the Health Research Board. Applied Partnership Awards, APA-2017-002.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for further information can be made to the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Doshi JA, et al. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32:101–14. 10.1086/657912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allegranzi B, Conway L, Larson E, et al. Status of the implementation of the World Health Organization multimodal hand hygiene strategy in United States of America health care facilities. Am J Infect Control 2014;42:224–30. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dadich A, Wyer M. Patient involvement in healthcare-associated infection research: a lexical review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018;39:710–7. 10.1017/ice.2018.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGuckin M, Govednik J. Patient empowerment and hand hygiene, 1997-2012. J Hosp Infect 2013;84:191–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seale H, Chughtai AA, Kaur R, et al. Empowering patients in the hospital as a new approach to reducing the burden of health care-associated infections: The attitudes of hospital health care workers. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:263–8. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, et al. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;3:CD004563 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alzyood M, Jackson D, Brooke J, et al. An integrative review exploring the perceptions of patients and healthcare professionals towards patient involvement in promoting hand hygiene compliance in the hospital setting. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:1329–45. 10.1111/jocn.14305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butenko S, Lockwood C, McArthur A. Patient experiences of partnering with healthcare professionals for hand hygiene compliance: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2017;15:1645–70. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis R, Parand A, Pinto A, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of strategies to encourage patients to remind healthcare professionals about their hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect 2015;89:141–62. 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ottum A, Sethi AK, Jacobs EA, et al. Do patients feel comfortable asking healthcare workers to wash their hands? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:1282–4. 10.1086/668419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michaelsen K, Sanders JL, Zimmer SM, et al. Overcoming patient barriers to discussing physician hand hygiene: do patients prefer electronic reminders to other methods? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:929–34. 10.1086/671727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pittet D, Panesar SS, Wilson K, et al. Involving the patient to ask about hospital hand hygiene: a national patient safety agency feasibility study. J Hosp Infect 2011;77:299–303. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGuckin M, Storr J, Longtin Y, et al. Patient empowerment and multimodal hand hygiene promotion: a win-win strategy. Am J Med Qual 2011;26:10–17. 10.1177/1062860610373138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Pinto A, et al. Patients' attitudes towards patient involvement in safety interventions: results of two exploratory studies. Health Expect 2013;16:e164–76. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' manual 2015: methodology For JBI Scoping Reviews. 2015.

- 18. Tartari E, Weterings V, Gastmeier P, et al. Patient engagement with surgical site infection prevention: an expert panel perspective. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017;6:45 10.1186/s13756-017-0202-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hill JN, Evans CT, Cameron KA, et al. Patient and provider perspectives on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a qualitative assessment of knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. J Spinal Cord Med 2013;36:82–90. 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng VCC, Wong SC, Wong IWY, et al. The challenge of patient empowerment in hand hygiene promotion in health care facilities in Hong Kong. Am J Infect Control 2017;45:562–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seale H, Chughtai AA, Kaur R, et al. Ask, speak up, and be proactive: empowering patient infection control to prevent health care-acquired infections. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:447–53. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wyer M, Jackson D, Iedema R, et al. Involving patients in understanding hospital infection control using visual methods. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1718–29. 10.1111/jocn.12779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Involve N. Briefing notes for researchers: involving the public in NHS, public health and social care research. UK: INVOLVE Eastleigh, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization. Guidelines for WHO guidelines. World Health Organisation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization. Clean care is safer care. 2018. http://www.who.int/gpsc/ipc/en/

- 26. Miller HM, Tong A, Tunnicliffe DJ, et al. Identifying and integrating patient and caregiver perspectives for clinical practice guidelines on the screening and management of infectious microorganisms in hemodialysis units. Hemodial Int 2017;21:213–23. 10.1111/hdi.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loveday HP, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ, et al. epic3: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect 2014;86:S1–70. 10.1016/S0195-6701(13)60012-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. See I, Shugart A, Lamb C, et al. Infection control and bloodstream infection prevention: the perspective of patients receiving hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 2014;41:37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ho ML, Seto WH, Wong LC, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted hand hygiene interventions in long-term care facilities in Hong Kong: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:761–7. 10.1086/666740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewardson AJ, Sax H, Gayet-Ageron A, et al. Enhanced performance feedback and patient participation to improve hand hygiene compliance of health-care workers in the setting of established multimodal promotion: a single-centre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:1345–55. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seale H, Novytska Y, Gallard J, et al. Examining hospital patients' knowledge and attitudes toward hospital-acquired infections and their participation in infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:461–3. 10.1017/ice.2014.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwappach DL, Frank O, Davis RE. A vignette study to examine health care professionals' attitudes towards patient involvement in error prevention. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:840–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wyer M, Iedema R, Hor SY, et al. Patient involvement can affect clinicians’ perspectives and practices of infection prevention and control: A “post-qualitative” study using video-reflexive ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017;16:1609406917690171. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nicholson Thomas E, Edwards L, McArdle P. Knowledge is Power. A quality improvement project to increase patient understanding of their hospital stay. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017;6:u207103. w3042 10.1136/bmjquality.u207103.w3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, et al. Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care: John Wiley and Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Foucault M. The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. Translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fox A. Intensive diabetes management: negotiating evidence-based practice. Can J Diet Pract Res 2010;71:62–8. 10.3148/71.2.2010.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brannigan ET, Murray E, Holmes A. Where does infection control fit into a hospital management structure? J Hosp Infect 2009;73:392–6. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Parsons T. The social system: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025824supp001.pdf (204.4KB, pdf)