Abstract

Objective

This study examined how a history of myocardial infarction (MI) in a person’s first-degree relatives affects that person’s risk of developing MI and autoimmune diseases.

Design

Nationwide population-based cross-sectional study

Setting

All healthcare facilities in Taiwan.

Participants

A total of 24 361 345 individuals were enrolled.

Methods

Using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan, we conducted a nationwide cross-sectional study of data collected from all beneficiaries in the Taiwan National Health Insurance system in 2015, of whom 259 360 subjects had at least one first-degree relative affected by MI in 2015. We estimated the absolute risks and relative risks (RRs) of MI and autoimmune disease in those subjects, and the relative contribution of genetic and environmental factors to their MI susceptibility.

Results

The absolute risks of MI for subjects with at least one affected first-degree relative and the general population were 0.87% and 0.56%, respectively, in 2015. Patients with affected first-degree relatives were significantly associated with a higher RR of MI (1.76, 95% CI: 1.68 to 1.85) compared with the general population. There was no association with a higher RR of autoimmune disease. The sibling, offspring and parental MI history conferred RRs (95% CI) for MI of 2.35 (1.96 to 2.83), 2.21 (2.05 to 2.39) and 1.60 (1.52 to 1.68), respectively. The contributions of heritability, shared environmental factors and non-shared environmental factors to MI susceptibility were 19.6%, 3.4% and 77.0%, respectively.

Conclusions

Individuals who have first-degree relatives with a history of MI have a higher risk of developing MI than the general population. Non-shared environmental factors contributed more significantly to MI susceptibility than did heritability and shared environmental factors. A family history of MI was not associated with an increased risk of autoimmune disease.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, family history, familial aggregation, autoimmune disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides quantitative estimates of relative risks of developing myocardial infarction (MI) and autoimmune disease in individuals with a family history of MI.

The strength of this study is the large size of the general population and the number of MI cases allowed detailed family history analyses.

We used database-linked family histories of MI, which are more reliable than self-reported family histories and have been validated.

We were not able to control for some important risk factors of MI, including smoking, obesity, blood pressure, lipid levels and physical activity.

The analysis of relative genetic and environmental contributions is based on the multifactorial liability model, where the results are subject to assumptions.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a leading cause of death worldwide and has several risk factors including family history.1–4 A meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies found a relative risk (RR) of 1.6 for future events in subjects with a family history of coronary heart disease (CHD).5 Although recall bias is a potential limitation, self-reported family history has been commonly used in previous studies.6–8 Family history of MI is generally available to physicians and several studies indicate that family history has been helpful in risk assessment.2 3 9 Two previous studies evaluated the incremental value of family history over conventional risk scores with conflicting results.10 11 Recent studies revealed that a detailed family history provides more information and helps to stratify MI risk.9 12 Only a few studies have evaluated the effect of affected sex or specific type of family relationships on MI risk.9 12

Atherosclerosis and autoimmune diseases share some pathogenic similarities and have a bidirectional relationship.13 14 Autoimmune diseases are characterised by chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation, which characteristics are also found in the development of atherosclerosis.14 15 These abnormalities may cause lipid peroxidation, platelet aggregation and arterial pathology.15 Therefore, patients with an autoimmune disease are more likely to develop premature and accelerated atherosclerosis than the general population.16 Given the similarities in immune-mediated inflammatory processes of the vascular system, some investigators have postulated that atherosclerosis is an immune-mediated disease.14 To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet evaluated the coaggregation of autoimmune disease in families with a history of MI.

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, we evaluate the risks of MI and autoimmune disease in individuals with a family history of MI in their first-degree relatives as well as estimate the genetic and environmental contribution to MI susceptibility.

Methods

Study population

The primary data source came from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains registration information and original claims data on all beneficiaries of National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan since its establishment in 1995. The study population consisted of all beneficiaries enrolled in the Taiwan NHI system in 2015. We used data from the registry for beneficiaries, the registry for patients with catastrophic illness, and data sets of ambulatory care expenditures and details of ambulatory case orders. All patient records in the database are identified by their unique national identification number. To ensure confidentiality, identification numbers were encrypted before being released for research, although the uniqueness of the encrypted identification was retained to facilitate data linkage for researchers. Methods of identifying first-degree relatives and family relationship ascertainment have been reported previously.17–19 Briefly, linear blood relatives and spouses can be directly identified using relationship indicators and unique national identification numbers. Full siblings of an individual are identified through shared parents. To analyse correlations among individuals from the same family, we grouped individuals into families according to their relationships.

Patient and public involvement

This is a database study using the Taiwan NHIRD. No patients or public were involved in developing the research question or outcome measures. No patients were involved in the design for this study. The results of the research were not disseminated to those study subjects. No patients or public were asked to advise on the interpretation or the writing up of the results.

Case definitions of MI and autoimmune disease

The case definition of MI was a patient with a primary discharge diagnosis of MI as defined in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code. We only included patients’ first diagnosis of MI. The diagnosis coding of MI obtained from the NHIRD has been validated with respect to its acceptable sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value.20 The case definition of autoimmune disease was a person with a catastrophic illness certification for a specific type of autoimmune diseases. The holders of a catastrophic illness certificate are entitled to a waiver for medical copayments. In order for a patient to receive a certificate for a catastrophic illness, the diagnosis must be supported by comprehensive clinical and laboratory assessments. This information is also required by the insurance administration for review by commissioned expert panels to confirm the diagnosis before the waiver approval.

Covariates

Factors that may confound or modify family associations were adjusted, including age, sex, family size, Charlson Comorbidity Index and socioeconomic factors (place of residence, occupation and income level). The place of residence for each individual was categorised according to the level of urbanisation, occupations were classified into five categories and income levels were categorised into sex-specific income quintiles.

Statistical analysis

We measured the prevalence of MI among individuals with affected relatives and the general population. An individual who met the case definition of MI between 1996 and 2015 and had valid insurance registration in 2015 was defined as a prevalent case. The total population in Taiwan was used to calculate the absolute risk of MI in 2015. The RR of MI was calculated as the cases of MI among individuals with an affected family member divided by the cases of MI in the general population. We calculated the RRs for subjects with an affected first-degree relative of any kinship or an affected spouse. Because kinship and sex may influence family risk, we calculated RRs separately according to kinship and sex of affected relatives. We applied the standard ACE model to quantify the influences of additive genetic factors (A), common environmental factors (C) and non-shared environmental factors (E) accounting for individual differences in a phenotype (P).21 The ACE model was expressed as: σ P 2=σ A 2+σ C 2+σ E,2 where σ p 2=total phenotypic variance; σ A 2=additive genetic variance; σ C 2=common environmental variance and σ E 2=non-shared environmental variance. The heritability was defined as the proportion of phenotypic variance that is attributable to genetic factors and was expressed as σ A 2/σ p 2 and the familial transmission was expressed as (σ A 2 + σ C 2)/σ p,2 which is the sum of heritability and common environmental variances. We used the polygenic liability model to calculate heritability and familial transmission.21–24 The sibling RR, spouse RR and the cases of MI in the general population were used to calculate the heritability and the familial transmission. The common environmental variance was calculated as the difference between familial transmission and heritability. All analyses were performed using SAS software V.9.3.

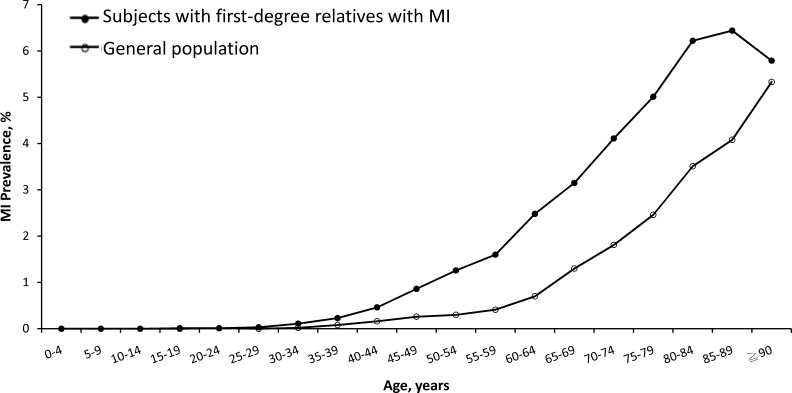

Results

The study population comprised 24 361 345 individuals (12 089 044 men and 12 272 301 women) enrolled in the NHI system in Taiwan in 2015, of whom 135 269 (33 762 women and 101 507 men) had MI, which is equivalent to an absolute risk of 0.56% (0.84% in men and 0.28% in women) (table 1). From the study population, 259 360 (1.06%) people had at least one first-degree relative with MI. Among these, 2255 had MI themselves (absolute risk 0.87%), 1502 had affected parents, 612 had affected offspring and 173 had affected siblings. For individuals with affected relatives, the age-specific prevalence of MI was significantly higher than in the general population (figure 1). Table 2 shows the absolute risk and RR of MI in individuals with an affected first-degree relative, according to relationship and sex of affected individuals and their families. Compared with the general population, patients with an affected first-degree relative had an RR of 1.76 (95% CI: 1.68 to 1.85) for MI. Although male subjects with affected relatives showed a higher prevalence of MI than female subjects (1.25% vs 0.34%), the RRs of MI for male (1.67, 95% CI: 1.59 to 1.76) and female (1.74, 95% CI: 1.57 to 1.93) subjects were similar. The RRs (95% CI) of MI were 2.35 (1.96 to 2.83) for those with an affected sibling, 2.21 (1.96 to 2.83) for those with an affected offspring, 1.60 (1.52 to 1.68) for those with an affected parent, 1.72 (1.60 to 1.84) for those with an affected father, 1.53 (1.43 to 1.65) for those with an affected mother and 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) for those with an affected spouse. RRs of MI for those with a family history of MI in one, two and three first-degree relatives were 1.73 (1.65 to 1.82), 3.47 (2.66 to 4.51) and 14.85 (4.95 to 44.52), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals with affected first-degree relatives with myocardial infarction and the general population

| Women | Men | |||||

| ≥1 affected relatives | General population | P value | ≥1 affected relatives | General population | P value | |

| No. of subjects | 109 371 | 12 272 301 | 149 989 | 12 089 044 | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 40.3 (21.0) | 39.6 (16.8) | <0.0001 | 38.9 (20.9) | 41.7 (15.6) | <0.0001 |

| MI (%) | 376 (0.3) | 33 762 (0.3) | <0.0001 | 1879 (1.3) | 101 507 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Place of residence (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Urban | 76 254 (69.7) | 7 740 136 (63.1) | 99 079 (66.1) | 7 309 940 (60.5) | ||

| Suburban | 28 195 (25.8) | 3 624 603 (29.5) | 43 568 (29.1) | 3 848 868 (31.8) | ||

| Rural | 4733 (4.3) | 872 384 (7.11) | 7086 (4.7) | 895 750 (7.4) | ||

| Unknown | 189 (0.2) | 35 178 (0.3) | 256 (0.17) | 34 486 (0.3) | ||

| Income levels (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 18 783 (17.2) | 2 062 900 (16.8) | 29 225 (19.5) | 2 310 684 (19.1) | ||

| Quintile 2 | 15 135 (13.8) | 1 838 185 (15.0) | 15 425 (10.3) | 1 506 475 (12.5) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 27 496 (25.1) | 3 658 895 (29.8) | 34 394 (22.9) | 3 207 226 (26.5) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 24 975 (22.8) | 2 411 506 (19.7) | 30 457 (20.3) | 2 241 214 (18.5) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 22 962 (21.0) | 2 298 595 (18.7) | 40 466 (27.0) | 2 821 626 (23.3) | ||

| Unknown | 20 (0.0) | 2220 (0.0) | 22 (0.0) | 1819 (0.0) | ||

| Occupation (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Dependents of the insured individuals | 26 186 (23.9) | 4 535 168 (37.0) | 26 276 (17.5) | 3 746 793 (31.0) | ||

| Civil servants, teachers, military personnel and veterans | 5481 (5.0) | 343 851 (2.8) | 9641 (6.3) | 570 840 (4.7) | ||

| Non-manual workers and professionals | 44 824 (41.0) | 3 642 834 (29.7) | 61 947 (41.3) | 3 934 252 (32.5) | ||

| Manual workers | 20 894 (19.1) | 2 609 974 (21.3) | 30 635 (20.4) | 2 286 403 (18.9) | ||

| Other | 11 986 (11.0) | 1 140 474 (9.3) | 21 490 (14.3) | 1 550 756 (12.8) | ||

MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 1.

Age-specific prevalence of myocardial infarction (MI) in subjects with MI in first-degree relatives and in the general population in Taiwan in 2015.

Table 2.

Relative risks for myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with MI in first-degree relatives

| Type of affected relative | Sex of affected relative | Sex of individual | No. of cases | Absolute risk (%) | Relative risk* (95% CI) |

| Any | Male | Male | 1198 | 1.08 | 1.84 (1.72 to 1.96) |

| Female | 307 | 0.35 | 1.76 (1.58 to 1.97) | ||

| All | 1505 | 0.76 | 1.92 (1.81 to 2.03) | ||

| Female | Male | 739 | 1.84 | 1.52 (1.41 to 1.63) | |

| Female | 73 | 0.32 | 1.69 (1.27 to 2.25) | ||

| All | 812 | 1.30 | 1.59 (1.48 to 1.70) | ||

| All | Male | 1879 | 1.25 | 1.67 (1.59 to 1.76) | |

| Female | 376 | 0.34 | 1.74 (1.57 to 1.93) | ||

| All | 2255 | 0.87 | 1.76 (1.68 to 1.85) | ||

| Parent | Male | Male | 756 | 0.74 | 1.67 (1.55 to 1.79) |

| Female | 40 | 0.05 | 1.21 (0.89 to 1.64) | ||

| All | 796 | 0.45 | 1.72 (1.60 to 1.84) | ||

| Female | Male | 706 | 1.80 | 1.50 (1.39 to 1.61) | |

| Female | 43 | 0.20 | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.69) | ||

| All | 749 | 1.23 | 1.53 (1.43 to 1.65) | ||

| All | Male | 1421 | 1.01 | 1.56 (1.48 to 1.64) | |

| Female | 81 | 0.08 | 1.22 (0.98 to 1.51) | ||

| All | 1502 | 0.63 | 1.60 (1.52 to 1.68) | ||

| Offspring | Male | Male | 302 | 8.02 | 2.15 (1.93 to 2.40) |

| Female | 260 | 3.34 | 1.95 (1.73 to 2.19) | ||

| All | 562 | 4.87 | 2.18 (2.01 to 2.36) | ||

| Female | Male | 26 | 7.60 | 2.40 (1.66 to 3.45) | |

| Female | 28 | 4.75 | 3.31 (2.32 to 4.72) | ||

| All | 54 | 5.79 | 2.94 (2.27 to 3.80) | ||

| All | Male | 326 | 7.94 | 2.16 (1.95 to 2.40) | |

| Female | 286 | 3.42 | 2.01 (1.80 to 2.25) | ||

| All | 612 | 4.91 | 2.21 (2.05 to 2.39) | ||

| Sibling | Male | Male | 154 | 2.95 | 2.48 (2.04 to 3.01) |

| Female | 9 | 0.23 | 1.20 (0.62 to 2.30) | ||

| All | 163 | 1.77 | 2.40 (1.99 to 2.90) | ||

| Female | Male | 8 | 1.49 | 1.48 (0.74 to 0.98) | |

| Female | 1 | 0.60 | 5.24 (0.77 to 35.54) | ||

| All | 10 | 1.15 | 1.75 (0.88 to 3.46) | ||

| All | Male | 162 | 2.81 | 2.40 (1.99 to 2.89) | |

| Female | 11 | 0.25 | 1.40 (0.74 to 2.65) | ||

| All | 173 | 1.72 | 2.35 (1.96 to 2.83) |

*Adjusted for age, gender, place of residence, quintiles of income levels, occupation and family size.

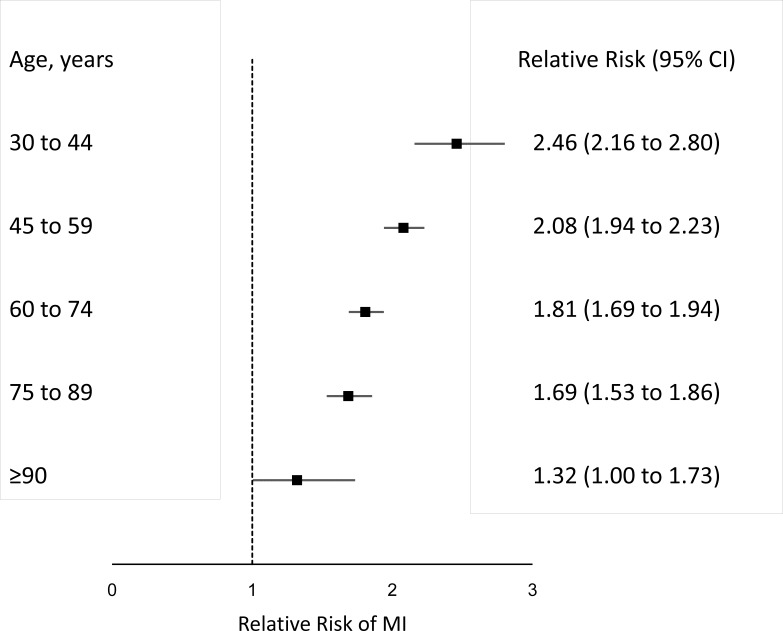

Table 3 shows the age distribution of MI cases in Taiwan in 2015, including individuals with MI in affected relatives and in the general population. In subjects with affected relatives, MI cases increased most notably from the age of 30, which was 10 years earlier than the general population. Figure 2 shows that the RRs of MI in subjects with affected relatives are stratified by age. Younger individuals were associated with a higher RR of MI.

Table 3.

Age-specific prevalence of myocardial infarction (MI) in individuals with a first-degree relative with MI and the general population in Taiwan in 2015

| Age, years | First-degree relative with MI | General population | ||||

| Case | Population | Absolute risk, % | Case | Population | Absolute risk, % | |

| 0–4 | 0 | 1198 | 0.00 | 4 | 1 051 252 | 0.00 |

| 5–9 | 0 | 2671 | 0.00 | 4 | 974 384 | 0.00 |

| 10–14 | 0 | 5835 | 0.00 | 13 | 1 153 257 | 0.00 |

| 15–19 | 0 | 11 300 | 0.00 | 37 | 1 505 997 | 0.00 |

| 20–24 | 1 | 17 328 | 0.01 | 75 | 1 748 236 | 0.00 |

| 25–29 | 7 | 23 469 | 0.03 | 179 | 1 784 709 | 0.01 |

| 30–34 | 40 | 37 278 | 0.11 | 595 | 2 095 030 | 0.03 |

| 35–39 | 88 | 37 707 | 0.23 | 1788 | 2 157 768 | 0.08 |

| 40–44 | 105 | 22 745 | 0.46 | 3539 | 1 853 362 | 0.19 |

| 45–49 | 198 | 22 939 | 0.86 | 6550 | 1 865 602 | 0.35 |

| 50–54 | 292 | 23 093 | 1.26 | 10 845 | 1 877 518 | 0.58 |

| 55–59 | 320 | 19 940 | 1.60 | 14 980 | 1 737 170 | 0.86 |

| 60–64 | 357 | 14 554 | 2.48 | 18 926 | 1 521 260 | 1.24 |

| 65–69 | 235 | 7453 | 3.15 | 17 146 | 9 82 469 | 1.75 |

| 70–74 | 166 | 4041 | 4.11 | 15 303 | 685 355 | 2.23 |

| 75–79 | 161 | 3214 | 5.01 | 15 542 | 578 084 | 2.69 |

| 80–84 | 139 | 2235 | 6.22 | 13 827 | 407 735 | 3.39 |

| 85–89 | 97 | 1507 | 6.44 | 10 510 | 258 837 | 4.06 |

| ≥90 | 49 | 847 | 5.79 | 5406 | 123 320 | 4.38 |

Figure 2.

The relative risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in subjects with affected first-degree relatives stratified by the age of the evaluated subjects compared with the general population.

Using the threshold liability model, we estimated the accountability for phenotypic variance of MI to be 19.6% for genetic factors (heritability), 3.4% for shared environmental factors and 77.0% for non-shared environmental factors.25 Given previously estimated parameters, the probability of a patient having sporadic MI was 83.1%.

Table 4 shows the prevalence and RRs for autoimmune diseases in individuals with first-degree relatives with MI compared with the general population. The RR (95% CI) in individuals with first-degree relatives with MI was 1.41 (1.00 to 2.00) for polymyositis/dermatomyositis, 1.14 (1.01 to 1.28) for systemic lupus erythematosus, 1.05 (0.76 to 1.44) for inflammatory bowel disease, 0.98 (0.78 to 1.23) for myasthenia gravis, 0.95 (0.67 to 1.35) for vasculitis, 0.94 (0.59 to 1.48) for systemic sclerosis, 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) for rheumatoid arthritis and 0.55 (0.32 to 0.92) for Behçet disease.

Table 4.

Relative risks (RRs) of autoimmune diseases in subjects with myocardial infarction (MI) in first-degree relatives

| Autoimmune diseases | Sex | Subjects with MI in first-degree relatives | General population | RR (95% CI)* | ||

| No. | Prevalence, % | No. | Prevalence, % | |||

| Congenital hypothyroidism | Male | 27 | 0.02 | 4347 | 0.04 | 0.95 (0.65 to 1.38) |

| Female | 54 | 0.05 | 6575 | 0.05 | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.18) | |

| All | 81 | 0.03 | 10 922 | 0.04 | 0.89 (0.71 to 1.10) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Male | 114 | 0.08 | 11 163 | 0.09 | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) |

| Female | 284 | 0.26 | 44 686 | 0.36 | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96) | |

| All | 398 | 0.15 | 55 849 | 0.23 | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) | |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Male | 32 | 0.02 | 2359 | 0.02 | 1.01 (0.70 to 1.46) |

| Female | 242 | 0.22 | 19 315 | 0.16 | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.26) | |

| All | 274 | 0.11 | 21 674 | 0.09 | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.21) | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Male | 28 | 0.02 | 2209 | 0.02 | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.29) |

| Female | 178 | 0.16 | 20 552 | 0.17 | 1.18 (1.04 to 1.34) | |

| All | 206 | 0.08 | 22 761 | 0.09 | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.28) | |

| Systemic sclerosis | Male | 7 | 0.00 | 461 | 0.00 | 1.06 (0.51 to 2.22) |

| Female | 11 | 0.01 | 1615 | 0.01 | 0.88 (0.49 to 1.57) | |

| All | 18 | 0.01 | 2076 | 0.01 | 0.94 (0.59 to 1.48) | |

| Polymyositis/dermatomyositis | Male | 9 | 0.01 | 646 | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.51 to 1.87) |

| Female | 22 | 0.02 | 1472 | 0.01 | 1.74 (1.15 to 2.62) | |

| All | 31 | 0.01 | 2118 | 0.01 | 1.41 (1.00 to 2.00) | |

| Behçet disease | Male | 7 | 0.00 | 883 | 0.01 | 0.53 (0.25 to 1.12) |

| Female | 7 | 0.01 | 1186 | 0.01 | 0.58 (0.28 to 1.21) | |

| All | 14 | 0.01 | 2069 | 0.01 | 0.55 (0.32 to 0.92) | |

| Vasculitis | Male | 23 | 0.02 | 3087 | 0.03 | 1.07 (0.71 to 1.60) |

| Female | 10 | 0.01 | 1958 | 0.02 | 0.79 (0.43 to 1.47) | |

| All | 33 | 0.01 | 5045 | 0.02 | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.35) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Male | 32 | 0.02 | 1798 | 0.01 | 1.21 (0.86 to 1.70) |

| Female | 5 | 0.00 | 1009 | 0.01 | 0.56 (0.23 to 1.34) | |

| All | 37 | 0.01 | 2807 | 0.01 | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.44) | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Male | 0 | 0.00 | 354 | 0.00 | 0.18 (0.03 to 1.27) |

| Female | 12 | 0.01 | 1234 | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.71) | |

| All | 13 | 0.01 | 1588 | 0.01 | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.25) | |

| Myasthenia gravis | Male | 41 | 0.03 | 2820 | 0.02 | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.50) |

| Female | 34 | 0.03 | 4312 | 0.04 | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.21) | |

| All | 75 | 0.03 | 7132 | 0.03 | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.23) | |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | Male | 86 | 0.06 | 4884 | 0.04 | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) |

| Female | 91 | 0.08 | 5841 | 0.05 | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.21) | |

| All | 177 | 0.07 | 10 725 | 0.04 | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | |

*Adjusted for age, gender, place of residence, quintiles of income levels, occupation, family size and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the familial aggregation of MI and coaggregation of autoimmune disease and MI in a population of more than 24 million. This analysis yielded five main findings: First, patients with at least one affected first-degree relative were 1.76-fold more likely to suffer from MI than the general population. The sibling, offspring, parental, paternal and maternal history of MI conferred RRs of MI of 2.35, 2.21, 1.60, 1.72 and 1.53, respectively. Second, for individuals with first-degree relatives with MI, MI events occurred 10 years earlier than for the general population, and younger individuals were associated with a higher RR of MI. Third, the more frequently MI occurred in an individual’s first-degree relatives, the higher that individual’s risk of MI. Fourth, shared environmental and genetic variance played only a minor role in MI susceptibility, but non-shared environmental factors accounted for more than three-quarters of the phenotypic variance in MI. Finally, a family history of MI in first-degree relatives was not associated with an increased risk for a majority of most of the autoimmune diseases.

The increased MI risk associated with family history found in our study aligns with results of previous case-controlled and population-based studies.3 5 7 9 10 12 A meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies yielded an RR of 1.60 (95% CI: 1.44 to 1.77) for CHD in individuals with an affected relative,5 which is similar to our estimate of 1.76 (95% CI: 1.68 to 1.85) for subjects with affected first-degree relatives. The RRs estimated in some studies were greater than ours, however.7 12 For instance, a nationwide population study in Denmark found high MI risks in subjects with an affected sibling (RR: 4.3, 95% CI: 3.53 to 5.23) or mother (RR: 2.4, 95% CI: 2.20 to 2.60),12 which is higher than our findings for these relationships (RR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.96 to 2.83 and RR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.48 to 1.70, respectively). The Danish study only included persons younger than 58 years of age, which is a younger study population than the present study. Another case-control study, of women aged 18–44 years, also found a higher MI risk in subjects with affected siblings.26 In the present study, we found that a family history of MI in first-degree relatives was associated with a higher RR of MI in younger subjects (figure 2). The more frequently MI occurred in an individual’s first-degree relatives, the higher that individual’s risk of MI. Similar findings were also observed in another Danish population study, which found that a history of MI in second-degree relatives was also associated with an increased risk of MI.9

Although familial aggregation of MI has been shown repeatedly in previous studies,1 7 12 it still has not been determined whether such aggregation is largely related to shared genes or environmental factors. Assuming spouses share similar familial environments but not genetics with other family members, they can be used to estimate the relative contribution of shared environmental factors to MI susceptibility.21–24 We found that shared environmental factors contributed minimally, only around 20% of phenotypic variance of MI was related to genetics. Non-shared environmental factors accounted for more than three-quarters of the phenotypic variance of MI. Compared with 43.9% of the genetic contribution of phenotypic variance in systemic lupus erythematosus,19 genetic variance in MI heritability can be regarded as a minor component.19 Given that multiple risk factors of MI, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus, have substantial heritability,27–29 the genetic contribution of MI may be even lower.

It is still debatable whether autoimmunity plays an essential role in the development of atherosclerosis,14 which is the underlying cause of MI in most cases.30 Patients with autoimmune diseases are at an increased risk of suffering accelerated atherosclerosis and premature MI.31 32 Despite findings in previous studies suggesting that autoimmune diseases share part of the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis,13 33 the extent and contributions to disease manifestation may differ. Atherosclerosis starts with endothelial injury followed by subendothelial accumulation of low-density lipoproteins, which triggers macrophages and type one T helper cells to form atherosclerotic plaques.34 35 Inflammation is initiated by the innate immune system oxidising low-density lipoproteins and is perpetuated by type one T helper cells that react to autoantigens from the apolipoprotein B100 in low-density lipoproteins.35 Chronic inflammation activated by the innate immune system is responsible for most atherosclerosis development, in which autoimmunity only plays a minor role. In the present study, we found that there was no coaggregation of autoimmune disease in families affected by MI. Future studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Our results have several implications. First, the study provides quantitative estimates of absolute risks and RRs, familial transmission and the proportion of sporadic cases of MI. These estimates are valuable in clinical counselling. Compared with the general population, younger subjects with first-degree relatives with MI were at a higher risk of developing MI in the future. The absence of coaggregation between MI and autoimmune diseases suggests that further evaluation of different pathogenic mechanisms is required.

The size of the cohort and the number of MI cases allowed detailed family history analyses and contribute to the strength of this study. Additionally, instead of using self-reported family histories of MI, we used database-linked family histories, which are more reliable and have been validated. Moreover, self-reported measures of family history in previous studies often included multiple events (CHD, stroke and death) or cases with varying severity (stable angina, unstable angina and MI).6 36 By comparison, we used only the primary discharge diagnosis of MI, which is a strict and validated endpoint that is subject to less misclassification and yields more interpretable estimates.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, this study was confined to Taiwan. Although it covered the entire population of Taiwan, the results may not be generalised and applied to other settings. Second, the NHIRD is primarily a health insurance database that contains only limited information on clinical diagnostic criteria. We did not have access to all information concerning traditional MI risk factors, including smoking, obesity, index, blood pressure, lipid levels and physical activity. Third, the analysis of relative genetic and environmental contributions should be interpreted with caution because it is based on the multifactorial liability model, where the results are subject to assumptions. However, published data on other diseases, such as schizophrenia and systemic lupus erythematosus, support the validity of this model.19 37 Finally, we cannot account for the effects of assortative mating, whereby spouses are more phenotypically similar than if mating were to occur at random in a population.

Conclusion

In this population-based cohort study, MI was found to aggregate in families, and non-shared environmental factors seemed to contribute more to the phenotypic variance of MI than genetic factors. There was no coaggregation of autoimmune disease in families affected by MI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (Grant CLRPG3D0043) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for designing, monitoring, analysing and interpreting the data. Part of the data was obtained via Applied Health Research Data Integration Service from the National Health Insurance Administration.

Footnotes

Contributors: Concept of study: C-FK and S-HC. Study design: C-LW, C-FK, Y-HY, M-YH and S-HC. Statistical analysis: C-LW and M-YH. Interpretation of results: C-LW, M-YH, C-TK and S-HC. Manuscript writing: C-LW and S-HC. All the authors provided inputs, expertise and critical review of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by research grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan (CMRPG3F0852 and CMRPG3G2031).

Disclaimer: The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of National Health Insurance Administration, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and by the National Health Research Institutes, which compile data for the National Health Insurance Research Database.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author (afen.chang@gmail.com).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Leander K, Hallqvist J, Reuterwall C, et al. Family history of coronary heart disease, a strong risk factor for myocardial infarction interacting with other cardiovascular risk factors: results from the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP). Epidemiology 2001;12:215–21. 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roncaglioni MC, Santoro L, D’Avanzo B, et al. Role of family history in patients with myocardial infarction. An Italian case-control study. GISSI-EFRIM Investigators. Circulation 1992;85:2065–72. 10.1161/01.CIR.85.6.2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lind C, Enga KF, Mathiesen EB, et al. Family history of myocardial infarction and cause-specific risk of myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism: the Tromsø Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014;7:684–91. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1–25. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P. Should your family history of coronary heart disease scare you? Mt Sinai J Med 2012;79:721–32. 10.1002/msj.21348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conroy RM, Mulcahy R, Hickey N, et al. Is a family history of coronary heart disease an independent coronary risk factor? Br Heart J 1985;53:378–81. 10.1136/hrt.53.4.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown DW, Giles WH, Burke W, et al. Familial aggregation of early-onset myocardial infarction. Community Genet 2002;5:232–8. 10.1159/000066684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kerber RA, Slattery ML. Comparison of self-reported and database-linked family history of cancer data in a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146:244–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ranthe MF, Petersen JA, Bundgaard H, et al. A detailed family history of myocardial infarction and risk of myocardial infarction--a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125896 10.1371/journal.pone.0125896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sivapalaratnam S, Boekholdt SM, Trip MD, et al. Family history of premature coronary heart disease and risk prediction in the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Heart 2010;96:1985–9. 10.1136/hrt.2010.210740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA 2012;308:788–95. 10.1001/jama.2012.9624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nielsen M, Andersson C, Gerds TA, et al. Familial clustering of myocardial infarction in first-degree relatives: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1198–203. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartoloni E, Shoenfeld Y, Gerli R. Inflammatory and autoimmune mechanisms in the induction of atherosclerotic damage in systemic rheumatic diseases: two faces of the same coin. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:178–83. 10.1002/acr.20322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsuura E, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, et al. Is atherosclerosis an autoimmune disease? BMC Med 2014;12:47 10.1186/1741-7015-12-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turiel M, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, et al. Cardiovascular injury in systemic autoimmune diseases: an update. Intern Emerg Med 2011;6(Suppl 1):99–102. 10.1007/s11739-011-0672-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hong J, Maron DJ, Shirai T, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatologic conditions. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2015;10:365–81. 10.2217/ijr.15.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Valdes AM, et al. Familial risk of sjögren’s syndrome and co-aggregation of autoimmune diseases in affected families: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1904–12. 10.1002/art.39127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuo CF, Luo SF, Yu KH, et al. Familial risk of systemic sclerosis and co-aggregation of autoimmune diseases in affected families. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:18 10.1186/s13075-016-1127-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Valdes AM, et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus and coaggregation of autoimmune diseases in affected families. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1518–26. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng CL, Lee CH, Chen PS, et al. Validation of acute myocardial infarction cases in the national health insurance research database in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2014;24:500–7. 10.2188/jea.JE20140076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, See LC, et al. Familial aggregation of gout and relative genetic and environmental contributions: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:369–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falconer DS. The inheritance of liability to diseases with variable age of onset, with particular reference to diabetes mellitus. Ann Hum Genet 1967;31:1–20. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1967.tb02015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reich T, James JW, Morris CA. The use of multiple thresholds in determining the mode of transmission of semi-continuous traits. Ann Hum Genet 1972;36:163–84. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1972.tb00767.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reich T, Rice J, Cloninger CR, et al. The use of multiple thresholds and segregation analysis in analyzing the phenotypic heterogeneity of multifactorial traits. Ann Hum Genet 1979;42:371–90. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1979.tb00670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haegert DG. Analysis of the threshold liability model provides new understanding of causation in autoimmune diseases. Med Hypotheses 2004;63:257–61. 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friedlander Y, Arbogast P, Schwartz SM, et al. Family history as a risk factor for early onset myocardial infarction in young women. Atherosclerosis 2001;156:201–7. 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00635-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soutar AK, Naoumova RP. Mechanisms of disease: genetic causes of familial hypercholesterolemia. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2007;4:214–25. 10.1038/ncpcardio0836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shih PA, O’Connor DT. Hereditary determinants of human hypertension: strategies in the setting of genetic complexity. Hypertension 2008;51:1456–64. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.090480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ali O. Genetics of type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes 2013;4:114–23. 10.4239/wjd.v4.i4.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Little WC, Downes TR, Applegate RJ. The underlying coronary lesion in myocardial infarction: implications for coronary angiography. Clin Cardiol 1991;14:868–74. 10.1002/clc.4960141103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:408–15. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. del Rincón ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Mechanisms of disease: atherosclerosis in autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2006;2:99–106. 10.1038/ncprheum0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bobryshev YV, Ivanova EA, Chistiakov DA, et al. Macrophages and their role in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and transcriptome analysis. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–13. 10.1155/2016/9582430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gisterå A, Hansson GK. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:368–80. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lloyd-Jones DM, Nam BH, D’Agostino RB, et al. Parental cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged adults: a prospective study of parents and offspring. JAMA 2004;291:2204–11. 10.1001/jama.291.18.2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chou IJ, Kuo CF, Huang YS, et al. Familial aggregation and heritability of schizophrenia and co-aggregation of psychiatric illnesses in affected families. Schizophr Bull 2017;43:1070–8. 10.1093/schbul/sbw159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.