Abstract

Oriented composite nanofibers consisting of porous silicon nanoparticles (pSiNPs) embedded in a polycaprolactone (PCL) or poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) matrix are prepared by spray nebulization from chloroform solutions using an airbrush. The nanofibers can be oriented by appropriate positioning of the airbrush nozzle, and they can direct growth of neurites from rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. When loaded with the model protein lysozyme, the pSiNPs allow the generation of nanofiber scaffolds that carry and deliver the protein under physiologic conditions (PBS, 37°C) for up to 60 days, retaining 75% of the enzymatic activity over this time period. The mass loading of protein in the pSiNPs is 36%, and in the resulting polymer/pSiNP scaffolds it is 2.5%. The use of pSiNPs that display intrinsic photoluminescence (from the quantum-confined Si nanostructure) allows the polymer/pSiNP composites to be definitively identified and tracked by time-gated photoluminescence imaging. The remarkable ability of the pSiNPs to protect the protein payload from denaturation, both during processing and for the duration of the long-term aqueous release study, establishes a model for the generation of biodegradable nanofiber scaffolds that can load and deliver sensitive biologics.

Keywords: rat ganglion cells, photoluminescence, controlled release drug delivery, protein therapeutics, cell guidance, airbrush, lysozyme, biologics, polycaprolactone, PLA, poly(lactide-co-glycolide), PLGA, time-gated photoluminescence imaging, tissue engineering

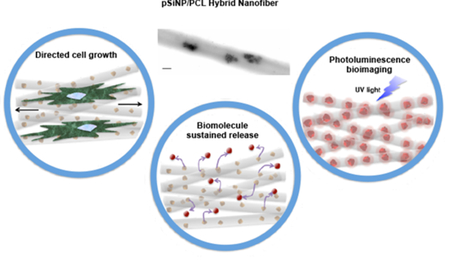

Graphical Abstract

Hybrid protein-eluting nanofibers are prepared using an airbrush. The protein is sequestered in a porous silicon nanoparticle, which retains the activity of the protein and allows its deposition from a non-aqueous solvent. The fibers can be aligned to direct cellular growth, and they are capable of releasing active protein for > 60 days.

Polymer nanofibers have been developed as scaffolds for numerous tissue engineering and nervous system repair applications due to their ability to mimic the topographical features of the extracellular environment and release a therapeutic payload at the target site.[1–8] However, they still remain largely irrelevant in the clinic.[9–10] This is in part due to the difficulty of readily fabricating nanofiber scaffolds that can deliver proteins or other biologics capable of stimulating tissue repair and regeneration. The vast majority of nanofibers are created using an electrospinning method, where an electric force is used to draw a polymer solution to a charged collector.[11] While this technique has shown utility in fabricating both randomly oriented and aligned nanofibers, there are two key drawbacks with this approach: (1) the fibers can only be fabricated on a surface in contact with the charged collector; and (2) polymer nanofibers are generally fabricated by dissolving the polymer in an organic solvent, making it difficult to load and retain the activity of biologics for extended release drug delivery applications.[12]

The most common method used to include sensitive biologics in polymer nanofibers is coaxial electrospinning, where a spinneret composed of two coaxial capillaries is used instead of a single nozzle.[13] Two solutions are fed through the inner/outer capillaries forming a compound droplet at the exit of the spinneret. When loading sensitive biologics, the inner core is commonly an aqueous solution containing proteins, DNA or oligonucleotides of interest. The outer shell is then formed from a hydrophobic polymer solution.[14] While coaxial electrospinning has substantial advantages, the process still has several drawbacks. These include: (i) instability of sensitive biological agents due to the high voltage, shearing forces at the core/shell interface, and rapid protein dehydration, (ii) increased difficulty in obtaining consistent nanofibers due to multiple phases, and (iii) inability to deposit nanofibers directly onto a surface of interest. However, nanoscale polymer fibers have led to improved outcomes in the development of tissue engineering scaffolds, stem cell differentiation, and in vitro cell culture environments that more closely resemble the in vivo milieus they are modeling. [15–22] Therefore, creating more versatile and readily fabricated polymer nanofibers that can elute biologic therapeutics and stimulate cellular growth is a key need for the successful translation of nanofiber tissue scaffolds to the clinic.

Mesoporous silicon is a biodegradable inorganic material that has been extensively investigated for photoluminescence-based imaging and drug delivery applications.[23–25] The biocompatibility and degradability of mesoporous silicon nanoparticles (pSiNPs) has been demonstrated in vivo.[26–27] The mechanism of dissolution of porous silicon (pSi) under in vivo conditions involves oxidation of silicon to form silicon oxide, followed by hydrolysis of the resulting oxide phase into water-soluble orthosilicic acid (Si(OH)4).[28] The high porosity of pSiNPs inherently provides a large pore volume to load therapeutics, which are delivered as the pSi skeleton degrades.[29–32] This degradation leads to changes in the intrinsic photoluminescent properties of pSi, which have been harnessed to provide a self-reporting drug delivery feature.[33] Of particular relevance to the present work, pSi has been shown to be capable of loading and protecting various sensitive biologics from proteolytic or nucleolytic degradation,[34–36] and it has been incorporated into a wide range of biomedically relevant polymer systems,[37–42] and larger, micron-scale particles of pSi have previously been incorporated into PCL-based scaffolds.[43–48] Most recently, a pSi host has been shown to afford protection to the protein lysozyme against degradation by non-aqueous solvents, providing a means to protect proteins from non-aqueous media.[36] Here we report a facile nebulization process that combines protein-loaded pSiNPs into polymer nanofibers and coats them onto uncharged surfaces. We find these hybrid nanofibers can guide cellular growth, exhibit photoluminescence, and release bioactive proteins (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Spray nebulization is used to produce nanofibers of polycaprolactone embedded with porous silicon nanoparticles (pSiNPs). The polymer fibers can direct cell growth, and the entrapped pSiNPs display an intrinsic photoluminescence that can be used to track degradation of the composite polymer/pSiNP scaffold. Although proteins are generally not soluble in or compatible with chloroform, the pSiNPs can sequester and protect a protein payload, allowing active protein to be co-formulated with the biodegradable polymer.

Spray nebulization of chloroform solutions 4% (w/w) of polycaprolactone (PCL) or 10 % (w/w) poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) by means of an airbrush[49] generated polymer nanofibers [Figure S1, Supporting Information]. The deposition distance and spraying angle were optimized to control fiber morphology, diameter, and alignment. We found that a distance of 20 cm from the airbrush nozzle to the collector reproducibly produced well-defined PCL nanofibers [Figure S2, Movie S1, Supporting Information]. Similar nanofibers (average diameter: 580–590 nm) could be generated using PLGA as the polymer source [Table S1, Supporting Information]. In order to prepare aligned fibers, the stream of material ejected from the airbrush nozzle was adjusted to strike the plane of the collector (typically, a glass microscope slide) at a 20° angle. Adjustment of this angle and the distance between the nozzle and the collector allowed optimization of the nanofiber morphology and degree of alignment [Figure S2, S3, Movie S2, Supporting Information].

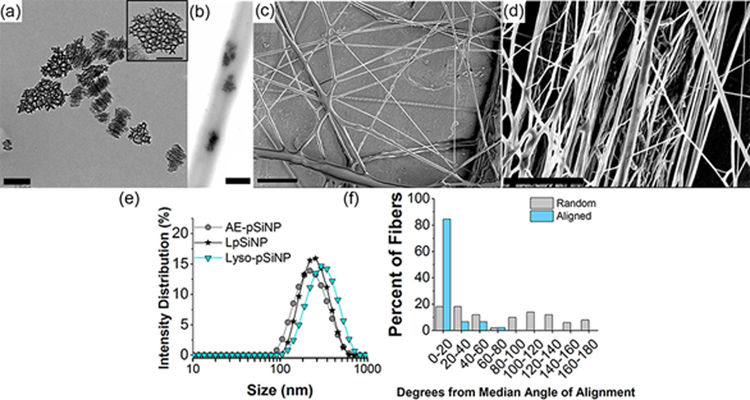

We next tested the spray nebulization method to assess if it would allow the incorporation of pSiNPs into the fibers. To prepare composites of the nanofibers with pSiNPs, as-etched nanoparticles prepared with a mean diameter of 210 nm [Table S2, Supporting Information] and nominal porosity of 46 ±2% were suspended in a chloroform solution containing 4% PCL and 0.2% pSiNPs by mass and the solution was nebulized as above to form nanofibers [Figure 1]. The hybrid pSiNP/PCL nanofibers displayed average diameters ranging from 500–600 nm [Table S1, Supporting Information], and the presence of pSiNPs was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy [Figure 1], infrared spectroscopy [Figure S4, Supporting Information] and energy dispersive x-ray elemental mapping [Figure S5, Supporting Information]. The PCL fiber mats were quite hydrophobic, displaying water contact angles of 125°, and this value did not differ significantly between either the pure PCL fiber scaffolds or those composed of pSiNP/PCL [Figure S6, Table S3, Supporting Information]. The inclusion of pSiNPs in the PCL matrix also did not alter the general fiber morphology or the degree of alignment of the oriented fibers [Figure S3, Supporting Information]. Similar composite fibers could be prepared using the common biodegradable polymer PLGA in place of PCL [Figure S7, Supporting Information].

Figure 1.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of (a) as-etched pSiNP (Scale = 200 nm, inset scale = 100 nm) and (b) hybrid nanofiber showing embedded as-etched-pSiNPs (scale = 400 nm). Scanning electron microscope images of (c) non-aligned (scale = 10 μm), and (d) aligned hybrid nanofibers (scale = 5 μm). (e) Size distribution of different pSiNP formulations measured by DLS. AE-pSiNP is as-etched porous silicon nanoparticles; LpSiNP is photoluminescent porous silicon nanoparticles (prepared by borate oxidation); Lyso-pSiNP is porous silicon nanoparticles loaded with lysozyme. (f) Quantification of angular orientation of fibers comparing non-aligned (Random) with uniaxially aligned (Aligned) hybrid nanofibers, created by spray nebulization. These PCL fibers contained as-etched pSiNPs as described in the text.

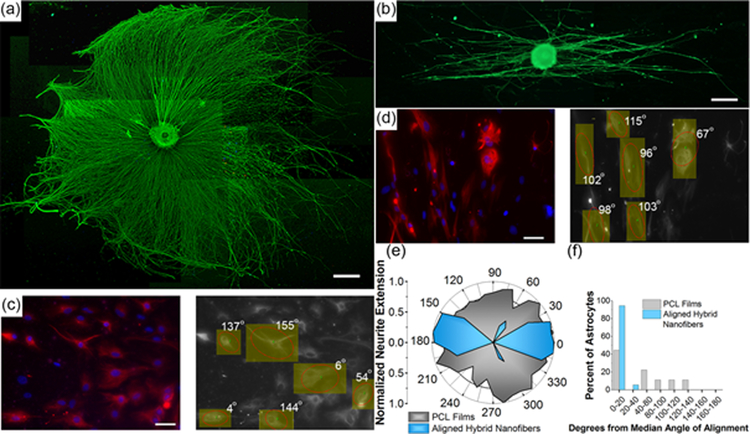

Controlling cellular growth and the direction of elongation is critical in regenerating injured tissues, especially in the nervous system where extending neurites must precisely connect across an area of injury in order to return functional use to the impacted tissues.[17, 50–52] PCL is one of a wide variety of artificial and natural materials used in constructing polymer fiber scaffolds that show efficacy in controlling and directing tissue growth.[1, 53–58] In the present case, we aimed to test the capability of the uniaxially-aligned PCL hybrid nanofibers to direct cellular extension in an in vitro nerve regeneration model. Whole dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were used to demonstrate the capability of the fibers to direct extending neurites. DRG were cultured on the aligned hybrid nanofibers for 72 hours and imaged using fluorescence microscopy [Figure 2]. Neurons of the DRG extended neurites along the fibers, and a polar histogram of neurite growth [Figure 2e] demonstrated a strong preference for bipolar neurite extension. Control DRG cultured on flat (non-fibrous) PCL films showed no preferential directional growth of neurites.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence microscope image of whole rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stained against neurofilament (NF200) on (a) flat PCL film and (b) aligned hybrid PCL nanofibers (scale bar = 500 μm). (c) Fluorescence image of astrocytes cultured on PCL films (left image; scale bar = 50 μm, red = GFAP, blue = DAPI). Image on the right shows OrientationJ[63] analysis of astrocyte alignment superimposed on the astrocyte image, demonstrating no preferential alignment. (d) Fluorescence image of astrocytes cultured on aligned hybrid PCL nanofibers (left image; scale bar = 50 μm, red = GFAP, blue = DAPI). Image on the right shows OrientationJ analysis of astrocyte alignment superimposed on the astrocyte image, demonstrating growth along the direction of the oriented hybrid nanofibers. (e) Polar histogram of neurite extension from cultured DRG (n=3) demonstrating pronounced alignment of neurite growth along the fiber direction with the uniaxial hybrid nanofibers (blue), and no preferential alignment of neurites cultured on PCL films (gray). (f) Orientation analysis comparing astrocytes cultured on uniaxially aligned hybrid nanofibers and on flat PCL films (n=3) using OrientationJ software. Astrocytes cultured on films displayed an average angle from the median angle of alignment of 50 ± 49°, while astrocytes cultured on aligned hybrid nanofibers showed significantly greater alignment, with an average angle from the median angle of alignment of 6 ± 8°.

In order to study the directed growth of single cells on the fibers, astrocytes were cultured on the aligned PCL nanofibers. Astrocytes are central nervous system (CNS) glia that are involved in synaptic maintenance, nutrient supply to neurons, neurotransmitter regulation, and several other functions of the healthy CNS.[59] They help form the glial scar following CNS injury,[60] so directing these cells with an artificial tissue scaffold holds the potential to improve neuronal regeneration by reducing scar formation at the injury borders. Astrocytes cultured on the hybrid nanofibers for 96 h exhibited good adhesion to the fibers, and they displayed a preferred orientation along the direction of fiber alignment [Figure 2]. The average angle of deviation from the median angle of cellular alignment was 6 ± 8°, whereas astrocytes cultured on control samples composed of flat PCL films showed no statistically significant preferred orientation [Figure 2e,f]. These experiments demonstrate that the aligned hybrid nanofibers created by the simple nebulization process behave similar to oriented, electrospun PCL fibers in their ability to direct the growth of single cells and the extension of growing neurites.[61–62]

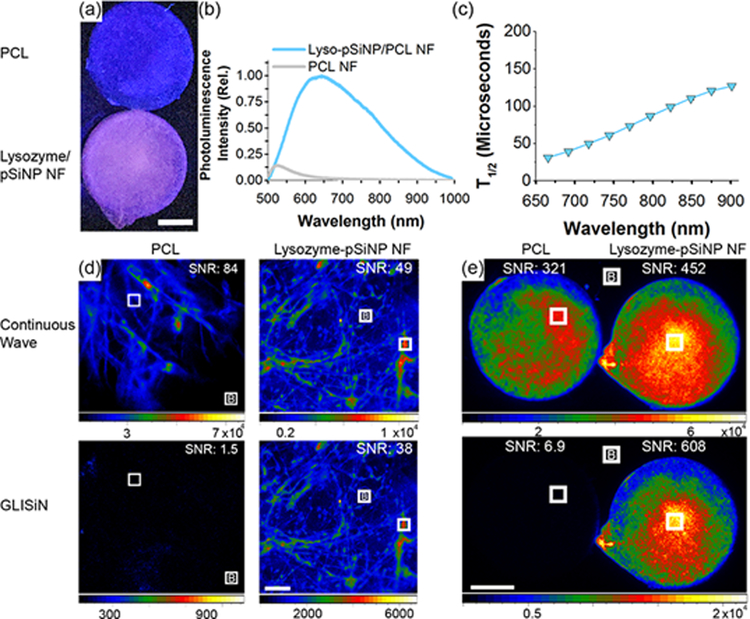

One important property of pSi is its photoluminescence (PL), which derives from quantum confinement effects in the silicon nanocrystallites that comprise the pSi skeleton.[64] Most biodegradable polymers lack the ability to be imaged and tracked in vivo following implantation, and we reasoned that photoluminescent pSi embedded in the PCL nanofibers that have near-infrared (NIR) PL emission and long-lived emissive excited state could be used to confirm proper implantation and monitor scaffold degradation in vivo. We prepared two types of photoluminescent pSiNPs from as-etched pSiNPs: one that was loaded with the test protein lysozyme and one that was empty. The empty particles were prepared following a borate oxidation procedure that activates photoluminescence,[65] and the lysozyme-loaded pSiNPs were prepared and the luminescence activated as discussed below. Both of these preparations generated photoluminescent pSiNPs by adding a passivating silicon oxide shell to the surface of the silicon skeleton.[66–68] We found that both types of luminescent nanoparticles could be incorporated into PCL nanofibers similar to the as-etched (non-luminescent) pSiNPs. The hybrid nanofibers exhibited broad PL emission (λem = 600–1000 nm) characteristic of pSiNPs, while no PL was observed for PCL control fibers [Figure 3, Figure S8, S9, Supporting Information]. Incorporation of either the empty or the lysozyme-loaded pSiNPs into PCL nanofibers did not result in a significant change in the peak emission wavelength from the nanoparticles [Figure S8, S9, Supporting Information]. As is typical of photoluminescence from quantum-confined silicon,[69–70] the hybrid nanofibers exhibited emission lifetimes of hundreds of microseconds [Figure S8, S9, Supporting Information], and the emission half life (T1/2) increased with increasing emission wavelength [Figure 3c].

Figure 3.

Steady-state and time-gated photoluminescence images of lysozyme-loaded pSiNP/PCL hybrid nanofiber scaffolds. (a) Image of PCL control (top) and hybrid nanofiber (bottom) when excited at with continuous λex = 365 nm light emitting diode (LED) (scale bar = 5mm), and (b) corresponding emission spectra for each scaffold. (c) Photoluminescence emission half-life of the hybrid nanofiber sample (lysozyme-loaded pSiNP/PCL), measured as a function of emission wavelength, λem. Emission half-life increases with increasing λem. (d) Luminescence microscope images of control PCL fibers and lyso-pSiNP/PCL hybrid nanofibers (10x objective, λex = 365 nm excitation, scale bar = 200 μm) obtained under steady state (continuous excitation, no time-gating) imaging conditions (top) and with time-gating (bottom). Time-gated (“GLISiN”, for Gated Luminescence Imaging of Silicon Nanoparticles) images were captured using a 5 μs excitation-acquisition delay gate. Time gating removes the prompt emission and scattered light from the image. Because pure PCL has no long-lived luminescence, the GLISiN image is black. Signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) are given for the regions of interest (ROIs) indicated with the white box in each of the images (B denotes the background ROI). (e) Low magnification photoluminescence images (λex = 365 nm, scale bar = 5mm) captured using a camera macro lens in order to survey large fields of PCL nanofibers (left) or hybrid nanofibers (right). Top two images were acquired under continuous wave excitation and bottom two images were acquired under GLISiN conditions. The GLISiN imaging parameters, SNRs and ROIs are defined as in (d).

The long emission lifetime of pSiNPs is a convenient feature for imaging of the material in vitro and in vivo, because it allows the suppression of the shorter-lived autofluorescence from endogenous organic fluorophores ubiquitous in cells, tissues, and many polymers. The time-gated method, known as Gated Luminescence Imaging of Silicon Nanoparticles (GLISiN), involves acquisition of the emission image at a time sufficiently delayed (>100 ns) from the pulsed excitation such that the prompt fluorescence from the organic fluorophores has decayed to baseline and is not detected.[71] In the current experiments, a pulsed ultraviolet light emitting diode (UV LED, λex = 365 nm) and a gate delay of 5 μs yielded microscopic GLISiN images of the pSiNP/PCL fibers with high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for either the empty [Figure S10, Supporting Information] or the lysozyme-loaded [Figure 3d,e] pSiNP/PCL fibers. Without time-gating, the regular fluorescence images could not distinguish autofluorescence of the PCL nanofiber controls from the pSiNP-containing fibers [Figure 3d,e, Figure S10 and Table S4, Supporting Information]. However, GLISiN images of the pSiNP/PCL fibers displayed SNR of between 20 and 80, whereas the SNR in GLISiN images of control PCL fibers (containing no pSiNPs) was < 2. Thus the GLISiN images afforded up to a 40-fold improvement in image contrast, and definitively established the presence of luminescent silicon in the fibers.

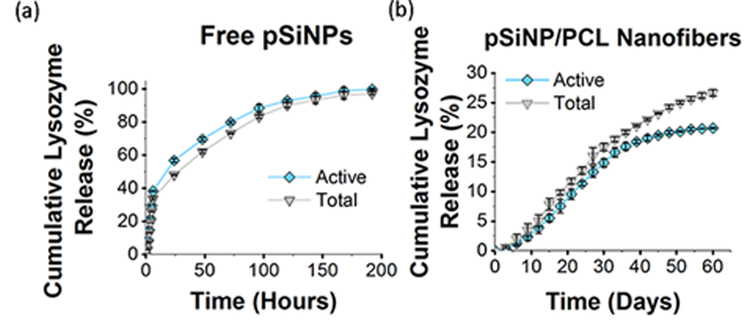

Next we evaluated the ability of the pSiNPs to protect a sensitive protein payload and enable slow release of the active protein in vitro. Controlled release of a biomolecule payload is of interest for inducing, enhancing, or selectively inhibiting cell growth along tissue scaffolds, and this is of particular interest in neuronal regeneration.[72] Protein-based therapeutics have posed one of the longstanding challenges in the area of drug eluting polymers, because the processing conditions used to prepare many bioresorbable polymer systems are incompatible with proteins, and the protein is often extensively denatured or hydrolyzed during formulation or during release.[73–74] For these experiments we used lysozyme as a test protein because there is a standard and sensitive assay for lysozyme activity that allows convenient quantification of denaturation or other degradative processes that the protein might undergo.[75–76] The loading procedure used for these experiments utilized a previously published phosphate buffer that oxidizes the pSiNPs, simultaneously trapping lysozyme in the pores and activating photoluminescence.[36] A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) total protein assay on the particles revealed a mass loading of lysozyme of 34 ± 1.8 %. As expected for a pore-filling process, the surface area and total pore volume of the pSiNPs decreased upon lysozyme loading [Figure S11, Table S5, Supporting Information]. The loaded protein imparted a positive overall surface charge to the pSiNPs–the zeta potential in neutral buffer increased from −22.3 ± 5.8 mV (for the empty, borate-oxidized pSiNPs) to +35 ± 2.5mV [Table S2, Supporting Information]. This increase in zeta potential upon protein loading is consistent with the pI of lysozyme (pI = 11.35),[77] indicating that the positive charge that the protein exhibits at neutral pH is imparted to the protein-loaded nanoparticles and consistent with the relatively high mass loading of protein. In vitro experiments indicated that the lysozyme payload was released into 37 °C, pH 7.4 buffer over a timespan of 8 days, with 55% of the protein released within the first 24 h. The lysozyme enzymatic activity assay showed that the protein released into solution retained 100% of its activity throughout the period of release [Figure 4, Figure S12, Supporting Information]. Thus the protein loading process does not interfere with or degrade the function of the lysozyme payload.

Figure 4.

Cumulative percent of lysozyme released from: (a) free pSiNPs and (b) pSiNPs incorporated in PCL fibers (pSiNP/PCL nanofibers). Experiment performed in PBS buffer at 37 °C and quantified in terms of total protein (from BCA assay) and active protein (from lysozyme enzymatic activity assay). Most of the protein is released from free pSiNPs within 8 days, and nearly 100% activity is retained (a). The initial burst release of protein is suppressed, and the release of protein is substantially extended when the pSiNPs are incorporated into a PCL nanofiber scaffold (b). For the pSiNP/PCL nanofibers, less than 5% of the lysozyme payload is released in the first 9 days. The activity of released lysozyme is >90% for the first 30 days, but at later times during the release process the activity of the protein released becomes lower; by day 60 released lysozyme exhibits 75% activity (n = 3, error bars ± 3 S.D.).

Lysozyme-pSiNPs were then loaded into hybrid nanofibers by spray nebulization (3.6% by mass lysozyme, 7% by mass pSiNPs; the effective concentration of protein in polymer was 36 μg/mg) and release of the protein into 37 °C, pH 7.4 buffer was quantified for a period of 60 days [Figure 4, Figure S12, Supporting Information]. Silicon content determined by ICP-AES was 7.9 ±0.45% (Table S6, Supporting Information). Chlorine content determined by suppressed ion chromatography was 26 ±8.49 ppm for PCL control nanofibers and 101 ±13.44 ppm for lyso-pSiNP nanofibers, showing a minimal amount of chloroform retention in the nanofiber scaffolds. The buffer eluent was sampled every 3 days, and both the total mass of lysozyme (BCA assay) and the mass of active lysozyme (lysozyme enzymatic activity assay) were determined at each time point. Burst release of the drug payload, a common and generally undesired characteristic of polymeric drug delivery systems[78–80] including electrospun fibers,[81] was not observed in the present case. Only 5% of the loaded lysozyme was released in the first 9 days, and the temporal release profile was relatively constant during the first 30 days of release (corresponding to ~15% of the total protein payload released). During this period of time, activity of released lysozyme was maintained at a high level (> 90%). For the latter half of the study (days 30–60), lysozyme release slowed, and the activity of the protein released was reduced significantly. By day 60, the activity of the total lysozyme released displayed 75% of its initial activity. Approximately 1/3 of the total loaded protein had been released by day 60, and at that time the polymer fibers were still observed in the release medium.

The stability of lysozyme in these experiments did not substantially differ from what has been seen for the enzyme when stored in buffer.[82] Lysozyme showed greater stability in the pSiNP/PCL nanofibers compared with many polymer and polymer fiber formulations,[10, 14] although the protein has been formulated into biodegradable polymers from water emulsion systems[83] and from water emulsion electrospinning systems[81] that displayed release and activity characteristics comparable to the present system. However, to our knowledge there are no non-aqueous routes to load active protein into polymers or polymer fibers, and the data here show that pSiNPs provide a unique means to incorporate a sensitive protein into a polymer fiber and to then deliver the active protein with a zero-order release profile for >60 days that does not display an early phase burst.

The nebulization approach described here provides a simple alternative to electrospinning that can be used to fabricate aligned polymeric nanofibers capable of directing cellular growth on a wide variety of surfaces, including electrical insulators. We demonstrated the incorporation of a protein delivery system based on a porous silicon host that showed superior compatibility with sensitive biologics. The ability of this system to provide sustained release of an active protein from a polymeric structure should be relevant to many advanced tissue engineering applications. The long-lived intrinsic photoluminescence originating from the silicon constituent provided an imaging feature that allows excellent rejection of signals from endogenous tissue fluorophores, providing a path for in vivo monitoring. We expect that the system will allow tuning of release rates and total doses of the therapeutic by adjustment of the chemistry and morphology of the pSi nanomaterial carrier and its concentration in the nanofiber matrix. Although this work only investigated a single protein, the approach is amenable to multiple drug formulations by adding different pSiNPs into the synthesis, each containing a different drug or drug combination. Due to the non-aqueous nature of the solvent used in fiber formation, the possibility of leaching or cross-contamination of water-soluble drugs during fabrication is minimized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation, under Grant no. CBET-1603177 (MJS) and by the National Institutes of Health, under Grant no. NINDS-RO1-NS089791 (NJA). JK acknowledges financial support from the UCSD Frontiers of Innovation Scholars Program (FISP) fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available online from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Jonathan M. Zuidema, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA).

Tushar Kumeria, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA), School of Pharmacy, University of Queensland, 20 Cornwall Street, Woolloongabba, Brisbane, Queensland 4102, Australia.

Dokyoung Kim, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, 26 Kyungheedae-Ro, Dongdaemun-Gu, Seoul 02447, Republic of Korea.

Jinyoung Kang, Department of Nanoengineering, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA).

Joanna Wang, Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA).

Geoffrey Hollett, Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA).

Xuan Zhang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA).

David S. Roberts, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA)

Nicole Chan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA).

Cari Dowling, Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10010 N Torrey Pines, La Jolla, CA, 92037 (USA).

Elena Blanco-Suarez, Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10010 N Torrey Pines, La Jolla, CA, 92037 (USA).

Nicola J. Allen, Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10010 N Torrey Pines, La Jolla, CA, 92037 (USA)

Mark H. Tuszynski, Veterans Administration Medical Center, 3350 La Jolla Village Drive, San Diego, CA, 92161 (USA), Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA)

Michael J. Sailor, Department of Chemistry and BiochemistryUniversity of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA, 92093 (USA) msailor@ucsd.edu

Literature Cited:

- [1].Yang F, Murugan R, Wang S, Ramakrishna S, Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2603–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bhardwaj N, Kundu SC, Biotechnol. Adv 2010, 28, 325–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ma Z, Kotaki M, Inai R, Ramakrishna S, Tissue Eng 2005, 11, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xu CY, Inai R, Kotaki M, Ramakrishna S, Biomaterials 2004, 25, 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li WJ, Laurencin CT, Caterson EJ, Tuan RS, Ko FK, J. Biomed. Mater. Res 2002, 60, 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yoo HS, Kim TG, Park TG, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2009, 61, 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2007, 59, 1392–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Barnes CP, Sell SA, Boland ED, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2007, 59, 1413–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ingavle GC, Leach JK, Tissue Eng. Part B Rev 2014, 20, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sperling LE, Reis KP, Pranke P, Wendorff JH, Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 1243–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dahlin RL, Kasper FK, Mikos AG, Tissue Eng. Part B Rev 2011, 17, 349–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Luu YK, Kim K, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Hadjiargyrou M, Control J. Release 2003, 89, 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sun ZC, Zussman E, Yarin AL, Wendorff JH, Greiner A, Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jiang HL, Wang LQ, Zhu KJ, Control Release J 2014, 193, 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee S, Leach MK, Redmond SA, Chong SYC, Mellon SH, Tuck SJ, Feng ZQ, Corey JM, Chan JR, Nature Meth 2012, 9, 917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rao SS, Nelson MT, Xue RP, DeJesus JK, Viapiano MS, Lannutti JJ, Sarkar A, Winter JO, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5181–5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Koh HS, Yong T, Chan CK, Ramakrishna S, Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3574–3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Capulli AK, MacQueen LA, Sheehy SP, Parker KK, Adv. Drug Del. Rev 2016, 96, 83–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Holzwarth JM, Ma PX, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9622–9629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Purcell EK, Naim Y, Yang A, Leach MK, Velkey JM, Duncan RK, Corey JM, Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3427–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI, Science 2004, 303, 1352–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chai YW, Lee EH, Gubbe JD, Brekke JH, PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Canham LT, Adv. Mater 1995, 7, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Salonen J, Laitinen L, Kaukonen AM, Tuura J, Bjorkqvist M, Heikkila T, Vaha-Heikkila K, Hirvonen J, Lehto VP, Control J. Release 2005, 108, 362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tasciotti E, Liu XW, Bhavane R, Plant K, Leonard AD, Price BK, Cheng MMC, Decuzzi P, Tour JM, Robertson F, Ferrari M, Nat. Nanotechnol 2008, 3, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Park J-H, Gu L, Maltzahn G. v., Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ, Nature Mater 2009, 8, 331–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Low SP, Voelcker NH, Canham LT, Williams KA, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2873–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Godin B, Gu JH, Serda RE, Bhavane R, Tasciotti E, Chiappini C, Liu XW, Tanaka T, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 94A, 1236–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McInnes SJP, Michl TD, Delalat B, Al-Bataineh SA, Coad BR, Vasilev K, Griesser HJ, Voelcker NH, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4467–4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kaasalainen M, Rytkonen J, Makila E, Narvanen A, Salonen J, Langmuir 2015, 31, 1722–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang HB, Liu DF, Shahbazi MA, Makila E, Herranz-Blanco B, Salonen J, Hirvonen J, Santos HA, Adv. Mater 2014, 26, 4497-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Canham LT, in Porous Silicon for Biomedical Applications (Ed.: Santos HA), 2014, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Koh Y, Jang S, Kim J, Kim S, Ko YC, Cho S, Sohn H, Coll. Surf. A 2008, 313, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kang J, Joo J, Kwon EJ, Skalak M, Hussain S, She Z-G, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ, Adv. Mater 2016, 28, 7962–7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wu C-C, Hu Y, Miller M, Aroian RV, Sailor MJ, ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6158–6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim D, Zuidema JM, Kang J, Pan Y, Wu L, Warther D, Arkles B, Sailor MJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15106–15109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bonanno LM, Segal E, Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 1755–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu WJ, Thapa R, Liu DF, Nissinen T, Granroth S, Narvanen A, Suvanto M, Santos HA, Lehto VP, Mol. Pharm 2015, 12, 4038–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Irani YD, Tian Y, Wang MJ, Klebe S, McInnes SJ, Voelcker NH, Coffer JL, Williams KA, Experimental Eye Research 2015, 139, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Soeriyadi AH, Gupta B, Reece PJ, Gooding JJ, Polym. Chem 2014, 5, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nan K, Ma F, Hou H, Freeman WR, Sailor MJ, Cheng L, Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 3505–3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Coffer JL, in Porous Silicon for Biomedical Applications (Ed.: Santos HA), 2014, pp. 470–485. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Coffer JL, Whitehead MA, Nagesha DK, Mukherjee P, Akkaraju G, Totolici M, Saffie RS, Canham LT, Phys. Status Solidi A-Appl. Mat 2005, 202, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kashanian S, Harding F, Irani Y, Klebe S, Marshall K, Loni A, Canham L, Fan DM, Williams KA, Voelcker NH, Coffer JL, Acta Biomater 2010, 6, 3566–3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Henstock JR, Ruktanonchai UR, Canham LT, Anderson SI, J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Med 2014, 25, 1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Whitehead MA, Fan D, Mukherjee P, Akkaraju GR, Canham LT, Coffer JL, Tissue Eng Part A 2008, 14, 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mukherjee P, Whitehead MA, Senter RA, Fan DM, Coffer JL, Canham LT, Biomed. Microdevices 2006, 8, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fan DM, Loni A, Canham LT, Coffer JL, Physica Status Solidi a-Applications and Materials Science 2009, 206, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tutak W, Sarkar S, Lin-Gibson S, Farooque TM, Jyotsnendu G, Wang D, Kohn J, Bolikal D, Simon CG Jr., Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2389–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hurtado A, Cregg JM, Wang HB, Wendell DF, Oudega M, Gilbert RJ, McDonald JW, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6068–6079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Xie J, Liu W, MacEwan MR, Bridgman PC, Xia Y, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1878–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gao MY, Lu P, Bednark B, Lynam D, Conner JM, Sakamoto J, Tuszynski MH, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1529–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Choi JS, Lee SJ, Christ GJ, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2899–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chen M, Patra PK, Warner SB, Bhowmick S, Tissue Eng 2007, 13, 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Venugopal J, Ramakrishna S, Tissue Eng 2005, 11, 847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Venugopal J, Ma LL, Yong T, Ramakrishna S, Cell Biol. Int 2005, 29, 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2007, 59, 1392–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Barnes CP, Sell SA, Boland ED, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2007, 59, 1413–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Allen NJ, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 2014, 30, 439–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Silver J, Miller JH, Nat Rev Neurosci 2004, 5, 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schnell E, Klinkhammer K, Balzer S, Brook G, Klee D, Dalton P, Mey J, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3012–3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Bockelmann J, Klinkhammer K, von Holst A, Seiler N, Faissner A, Brook GA, Klee D, Mey J, Tissue Eng. Part A 2011, 17, 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rezakhaniha R, Agianniotis A, Schrauwen JTC, Griffa A, Sage D, Bouten CVC, van de Vosse FN, Unser M, Stergiopulos N, Biomech. Model Mechan 2012, 11, 461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cullis AG, Canham LT, Nature 1991, 353, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Joo J, Cruz JF, Vijayakumar S, Grondek J, Sailor MJ, Adv. Funct. Mater 2014, 24, 5688–5694. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Petrova-Koch V, Muschik T, Kux A, Meyer BK, Koch F, Lehmann V, Appl. Phys. Lett 1992, 61, 943–945. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gongalsky MB, Osminkina LA, Pereira A, Manankov AA, Fedorenko AA, Vasiliev AN, Solovyev VV, Kudryavtsev AA, Sentis M, Kabashin AV, Timoshenko VY, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 24732–24732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gelloz B, Koshida N, Appl. Phys. Lett 2009, 94, 201903. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Xie YH, Wilson WL, Ross FM, Mucha JA, Fitzgerald EA, Macaulay JM, Harris TD, J. Appl. Phys 1992, 71, 2403–2407. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sa’ar A, J. Nanophotonics 2009, 3, 032501. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Joo J, Liu X, Kotamraju VR, Ruoslahti E, Nam Y, Sailor MJ, ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6233–6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Keefe KM, Sheikh IS, Smith GM, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Mader K, Gallez B, Liu KJ, Swartz HM, Biomaterials 1996, 17, 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Kang J, Lambert O, Ausborn M, Schwendeman SP, Int. J. Pharm 2008, 357, 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chen MY, Klunk MD, Diep VM, Sailor MJ, Adv. Mater 2011, 23, 4537–4542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Yoon JY, Garrell RL, Choi SW, Kim JH, Kim WS, Aiche J 2005, 51, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wetter LR, Deutsch HF, J. Biol. Chem 1951, 192, 237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Fredenberg S, Wahlgren M, Reslow M, Axelsson A, Int. J. Pharm 2011, 415, 34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wischke C, Schwendeman SP, Int. J. Pharm 2008, 364, 298–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Yeo Y, Park K, Arch. Pharm. Res 2004, 27, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Yang Y, Li X, Qi M, Zhou S, Weng J, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2008, 69, 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Determan AS, Wilson JH, Kipper MJ, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3312–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Bezemer JM, Radersma R, Grijpma DW, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J, van Blitterswijk CA, Control Release J 2000, 64, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.