Summary

Background

Rising annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation have been reported in England and some other higher-income countries, but the reasons for this increase are unclear. We aimed to describe the extent of variations in involuntary annual hospitalisation rates between countries, to compare trends over time, and to explore whether variations in legislation, demographics, economics, and health-care provision might be associated with variations in involuntary hospitalisation rates.

Methods

We compared annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation between 2008 and 2017 (where available) for 22 countries across Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. We also obtained data on national legislation, demographic and economic factors (gross domestic product [GDP] per capita, prevalence of inequality and poverty, and the percentage of populations who are foreign born, members of ethnic minorities, or living in urban settings), and service characteristics (health-care spending and provision of psychiatric beds and mental health staff). Annual incidence data were obtained from government sources or published peer-reviewed literature.

Findings

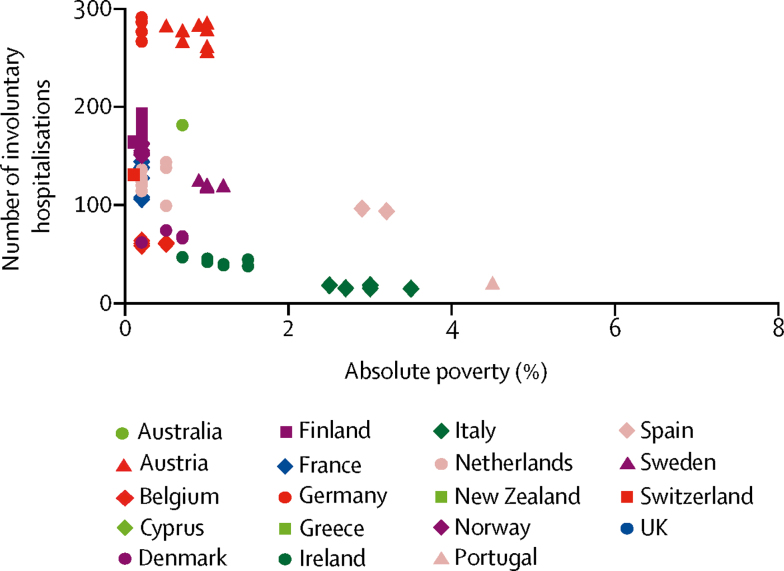

The median rate of involuntary hospitalisation was 106·4 (IQR 58·5 to 150·9) per 100 000 people, with Austria having the highest (282 per 100 000 individuals) and Italy the lowest (14·5 per 100 000 individuals) most recently available rates. We observed no relationship between annual involuntary hospitalisation rates and any characteristics of the legal framework. Higher national rates of involuntary hospitalisation were associated with a larger number of beds (β coefficient 0·65, 95% CI 0·10 to 1·20, p=0·021), higher GDP per capita purchasing power parity (β coefficient 1·84, 0·30 to 3·38, p=0·019), health-care spending per capita (β coefficient 15·92, 3·34 to 28·49, p=0·013), the proportion of foreign-born individuals in the population (β coefficient 7·32, 0·44 to 14·19, p=0·037), and lower absolute poverty (β coefficient −11·5, −22·6 to −0·3, p=0·044). There was no evidence of an association between annual involuntary hospitalisation incidence and any other demographic, economic, or health-care indicator.

Interpretation

Variations between countries were large and for the most part unexplained. We found a higher annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation to be associated with a lower rate of absolute poverty, with higher GDP and health-care spending per capita, a higher proportion of foreign-born individuals in a population, and larger numbers of inpatient beds, but limitations in ecological research must be noted, and the associations were weak. Other country-level demographic, economic, and health-care delivery indicators and characteristics of the legislative system appeared to be unrelated to annual involuntary hospitalisation rates. Understanding why involuntary hospitalisation rates vary so much could be advanced through a more fine-grained analysis of the relationships between involuntary hospitalisation and social context, clinical practice, and how legislation is implemented in practice.

Funding

Commissioned by the Department of Health and funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) via the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit.

Introduction

In England, the involuntary hospitalisation of patients on psychiatric grounds is regulated by the Mental Health Act (MHA; 1983). The MHA was last amended in 2007, and since then the number of involuntary hospitalisations (ie, admission to a psychiatric hospital involving an involuntary hospitalisation order) has increased from 43 356 in 2007–08 (83·7 per 100 000 individuals) to 63 049 in 2015–16 (114·1 per 100 000 individuals),1 a rise of 36·3%. Concerns about this rise were an important factor in the government's decision in 2017 to commission an independent review of the MHA.2 The present Article was part of research work commissioned for that review, allowing policy makers to consider how the incidence of involuntary hospitalisation and legislative frameworks compare internationally with those in England, and whether there is any evidence that variations in legislative frameworks might affect these annual rates.

Annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation have previously been reported to vary widely between countries, with little evidence available as to how much this variation is due to differences in domestic legislation or to sociodemographic, geographical, or health-care system variations. The study by Salize and Dressing3 is one of few to present international data on this topic. Their study, published in 2004, found that rates of involuntary hospitalisation varied greatly across Europe, from six per 100 000 individuals in Portugal to more than 200 per 100 000 in Finland, and that the mandatory involvement of a legal representative during the process of involuntary hospitalisation appeared to be associated with a lower proportion of hospital admissions being involuntary than when a legal representative was not present (p=0·03). No other aspect of legislation considered was associated with either this proportion or with a rate of detention per 100 000 population. Stefano and Ducci4 approached this issue by reviewing already published epidemiological studies from the 15 member states of the EU at the time, and related them to variations in legislation. They also found wide variation across Europe. Furthermore, they argued that, contrary to the findings of Salize and Dressing,3 there was probably a difference in annual involuntary hospitalisation rates between countries that allow for involuntary hospitalisation on the basis of patient's need for treatment and those requiring a justification on grounds of risk. Thus, there has been little investigation of international variations in involuntary admissions, and a consensus on the source of these variations has not been reached in the papers that are available. The research literature also includes no recent international comparisons of time trends, so that in England, policy makers could not assess whether rising rates of involuntary hospitalisation were primarily an English or international phenomenon.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

On Jan 8, 2018, we searched PubMed and Embase using the search terms “compulsory” or “involuntary” with “hospitalisation” or “admission”, and “commit*”, “detention”, or “detain*” with “mental illness”, “mental health”, or “psychiatr*”. We placed no language restrictions on the search. We identified a small body of literature that investigated international variations in annual detention rates and the relationship between national involuntary hospitalisation rates and legislation, but studies that have been published since 2008 are scarce. This literature showed that annual involuntary hospitalisation rates across Europe varied widely, with one paper from 2004 reporting Portugal to have six involuntary hospitalisations per 100 000 individuals, whereas Finland had 218 involuntary hospitalisations per 100 000 individuals. The same publication found some evidence that countries requiring the involvement of a legal representative in the involuntary hospitalisation process had lower rates of involuntary hospitalisation. Another study from 2008 found some evidence that annual involuntary hospitalisation rates differed between countries that allow risk as grounds for involuntary hospitalisation and those that only allow this type of hospitalisation on the basis of a need for treatment.

Added value of this study

For our study of involuntary hospitalisation from 22 European countries and Australia and New Zealand, we obtained data since 2008, predominantly from government sources, and reported at least 1 year of data for all countries. As well as updating previous literature, we include more countries, compare time trends between countries, and our study is to our knowledge the first to explore the relationship between sociodemographics, economics, and health-care provision and involuntary hospitalisation rates across high-income countries. Consistent with previous literature, we found that annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation varied widely between countries. Wealthier countries, and those with higher psychiatric inpatient provision, tended to have higher rates of involuntary hospitalisation. However, these factors could not explain the substantial variation between countries.

Implications of all the available evidence

There are many challenges in obtaining reliable data and making valid comparisons between countries, but as when last investigated at the beginning of the 21st century, there appear to be strikingly large variations in rates of involuntary admission between countries. Wealthier countries and those with greater numbers of inpatient beds tend to have slightly more involuntary hospitalisations. However, the large variations between countries are largely unexplained by associations with aspects of the legal systems or the sociodemographic or service system characteristics of the countries included in our analysis. Researchers and people involved with national statistics could work together to develop better, internationally standardised ways of collecting the data. Better data from more countries would help to understand why involuntary hospitalisation rates vary so much, and what might underlie the different patterns of change over time seen in different countries. The factors we have explored do not, so far, offer a clear basis for understanding this wide variability. A better explanation of variations in involuntary hospitalisation rates is desirable, so as to understand what drives involuntary hospitalisations, the extent to which involuntary hospitalisations reflect a clinical need being met, and whether they might be preventable, which would reflect a form of unwarranted variation. There are more legal, sociodemographic, economic, and health-care factors that researchers could investigate to develop a more nuanced understanding of the sources of variations and fluctuations, such as the availability and accessibility of community-based alternatives to hospitalisation, the quality of continuing community care and the social circumstances in which people with mental illnesses live, and the ways in which risk is assessed and legal criteria for detention are applied.

Apart from the legal system, other factors that could explain the variations in involuntary hospitalisation rates are socioeconomic characteristics and the extent to which mental health-care service is provided. Various associations have been shown with annual involuntary hospitalisation rates at an area level. In England, a moderate-to-strong correlation (r −0·69, p<0·01) between declining psychiatric bed numbers per 100 000 individuals and increasing rates of civil involuntary hospitalisation has been reported.5 A greater demand for a limited number of beds might arguably drive up involuntary hospitalisation in a number of ways:5, 6 patients discharged early from wards with a shortage of beds might be more likely to relapse and be readmitted; involuntary rather than voluntary hospitalisation might be used to flag severity of need; and where a high proportion of inpatients are involuntarily hospitalised, inpatient wards might become less therapeutic and more custodial, further driving up involuntary hospitalisation. Furthermore, annual involuntary hospitalisation rates are consistently found to be higher in urban areas and in areas with greater social deprivation than in rural areas or areas with low social deprivation.7, 8 There is also a particularly well supported association between annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation and the proportion of the population who are black and minority ethnic (BAME) or foreign born.8

The aims of the present study were to compare rates of involuntary hospitalisation per 100 000 individuals in England and trends over time with those in other high-income countries with similarly developed mental health-care services and legislation; to compare national legislations and consider their relationship with rates of involuntary hospitalisation; and to explore the association between involuntary hospitalisation rates and demographic, economic, and health-care provision indicators.

Methods

Data collection

In our study, we compared annual involuntary hospitalisation rates between 2008 and 2017 (where available) in 22 countries: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Involuntary hospitalisation rates were for the number of patients who were subject to an involuntary hospitalisation order during an admission in psychiatric hospital. These orders were not necessarily issued at the point of admission, but could be issued after admission.' We chose countries on the basis of them having well developed mental health-care systems with substantial progress in deinstitutionalisation,9 a population of more than 1 million people, and available involuntary hospitalisation data. Eastern European countries formerly within or allied to the Soviet Union were not included, given that the history of their mental health services and the resources available differ substantially from those of western Europe (eg, relatively heavy reliance on psychiatric hospitals, with limited community service development).9 Thus, the scope for and validity of direct comparisons are limited. Additionally, during initial scoping we found that data were generally less readily obtainable in eastern European countries. We obtained annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation per 100 000 individuals in the general population via national official organisations, peer-reviewed literature, or the WHO Mental Health Atlas.10 We provide a full description of data sources (table 1). When data were not readily accessible, we obtained them with the assistance of key informants, who were mental health professionals or academics with relevant expert knowledge based in each country. WHO Mental Health Atlas data were not used throughout our analysis, as they are only published every 3 years and does not cover all countries. We obtained annual figures from 2008 to 2017 when available. We chose to focus on a 10 year period, because our initial scoping suggested that this was the period for which we would be able to obtain data for a substantial number of countries. When only the total number of annual psychiatric hospitalisations was available, we calculated incidence data using population figures obtained from the World Bank30 or the UK Office of National Statistics.31 These countries are reported in table 1. We excluded hospital admissions of forensic patients because the rationale and legal frameworks regulating their detention are distinct from those considered here. We also excluded community treatment orders and similar community-based involuntary assessment or treatment orders to maintain a focus on involuntary hospitalisation.

Table 1.

Annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation per 100 000 individuals by country

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average annual percentage change* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia†11 | .. | 182·3 | 181·8 | 172·9 | 181·3 | 187·6 | 189·3 | .. | 227·3 | .. | 3·44% |

| Austria12 | 255·0 | 260·0 | 265·0 | 277·0 | 284·0 | 281·0 | 276·2 | 282·0 | .. | .. | 1·48% |

| Belgium13 | 58·3 | 60·5 | 60·9 | 60·3 | 60·3 | 61·1 | 63·4 | 63·6 | .. | .. | 1·26% |

| Cyprus†14 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 98·7 | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Denmark†‡ | .. | .. | .. | .. | 61·8 | 66·1 | 68·1 | 73·9 | 74·6 | 58·5 | −0·42% |

| England†§1 | 83·7 | 84·1 | 87·5 | 86·3 | 89·9 | 92·7 | 97·0 | 105·4 | 114·1 | 82·2¶ | 4·00% |

| Finland†15 | 193·2 | 181·0 | 169·3 | 164·3 | 156·2 | 153·6 | 152·1 | 152·8 | 151·4 | .. | −2·97% |

| France16 | 108·0 | 106·0 | 127·4 | 138·1 | 138·4 | 144·3 | 140·0 | .. | 4·71% | ||

| Germany†17 | 150·6 | 153·1 | 155·0 | 168·5 | 170·6 | 170·2 | 170·8 | 173·0 | .. | .. | 1·93% |

| Greece18 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 78·9 | .. |

| Northern Ireland†19 | .. | 38·5 | 37·8 | 39·4 | 41·9 | 44·4 | 45·0 | 46·7 | 48·4 | 45·4 | 2·16% |

| Italy20 | .. | .. | 17·9 | .. | 18·0 | 14·8 | 14·9 | 14·5 | .. | .. | −3·86% |

| The Netherlands†21 | 99·2 | 114·3 | 119·9 | 124·0 | 127·5 | 136·1 | 138·2 | 143·7 | 152·0 | 155·3 | 5·18% |

| New Zealand†‖ | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 70·8 | 73·2 | 73·6 | 71·2 | 73·3 | 0·91% |

| Ireland†§22 | .. | 56·1 | 57·3 | 53·3 | 57·7 | 53·5 | 53·0 | 57·5 | 55·4 | .. | 0·01% |

| Norway23 | .. | .. | 162·7 | 162·1 | 153·3 | 151·4 | 155·3 | 150·9 | .. | .. | −1·45% |

| Portugal24 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 18·2 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Scotland†§25 | 74·9 | 75·0 | 74·1 | 77·6 | 76·8 | 80·1 | 81·7 | 88·3 | 91·0 | 98·4 | 3·13% |

| Spain†26 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 96·4 | 93·6 | 108·6 | 121·9 | 8·45% |

| Sweden†27 | .. | .. | .. | 117·3 | 118·7 | 118·0 | 123·2 | 116·5 | 115·5 | −0·25% | |

| Switzerland28 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 131·1 | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Wales†§29 | 43·9 | 52·1 | 44·4 | 55·2 | 45·9 | 46·7 | 54·4 | 61·7 | 64·3 | 56·8 | 3·96% |

| UK** | .. | 81·5 | 83·8 | 83·5 | 86·2 | 88·6 | 92·8 | 100·8 | 107·9 | 4·13% |

For each country, the percentage change was first calculated for available years then summarised as a mean.

Annual incidence calculated from the total number of involuntary hospitalisations and population data or other available data.

Data received from Danish state police via email.

Not used in demographic, economic, and health-care analyses; data from the whole of the UK was used instead.

Excluded because of known underreporting.

Data received from the Office of the Director of Mental Health and Addiction Services, New Zealand via email.

Calculated using data for England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland and population data from the Office of National Statistics.11

Panel. Lived experience commentary by Stephen Jeffreys and Stella Branthonne-Foster.

We have personal experience of community and inpatient mental health services. We commented on drafts of this Article but we were not involved in design of the project. The Article might both fascinate and frustrate. The research outlines key aspects of legislative systems but cannot provide detail; it highlights surprising differences in rates of detention but leaves specific explanations for future exploration.

The Article finds no association between detentions and legislative differences, and demographic and socioeconomic association is scarce. It identifies variations in clinical practice and alternatives to detention as potential explanatory factors. Substantial variations in legislation are documented, but we note that all countries allow detention and compulsory treatment under specified conditions. The absence of association with legislative variations should not be taken as evidence that legislation and rights are not important for people in mental health crisis, or that transition to less coercive systems cannot be driven by adoption of rights-based legislative approaches, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The huge variations in overall annual rates of detention demand further explanation, for exploration of the differing policy and clinical practice drivers and service-user experiences of their mental health systems. Do the much lower rates of involuntary hospitalisation in Italy offer lessons and hope for less reliance on detention elsewhere? Why have detention rates in neighbouring Wales consistently been 60% lower than in England, when the same legislation applies? Why are detention rates in Austria so much higher than elsewhere in Europe? How are Finland and Norway managing to reduce detentions, whereas these have been increasing in England, France, and Spain?

Further exploration should include consideration of informal admissions, length of detention, community alternatives, treatment of marginalised communities, and the more subjective consequences of recession and prevailing political economic ideologies, such as neoliberalism.

We developed a profile of the legislation for each country, which summarised the legislation relevant to eight topics (full details are in the appendix): the essential criteria for involuntary hospitalisation; who is entitled to issue an involuntary hospitalisation order (including police in cases of emergency); whether there is any obligation for a legal representative for the patient to be present at the assessment or to be consulted when authorising the admission; whether there is a legal requirement to consult a relative or next of kin; which types of involuntary hospitalisation orders are available; the arrangements for appealing an involuntary hospitalisation order; the patient's legal rights (eg, to legal representation); and how patients' human rights are protected. We obtained details of legislation regulating involuntary hospitalisation and its practice via governmental websites or with the assistance of key informants with relevant language skills and familiarity with national systems. Profiles for every country were reviewed by key informants to confirm their accuracy and comprehensiveness. Key informants were psychiatrists or mental health legal experts based in the relevant countries who were familiar with details of the involuntary hospitalisation process in their countries. We selected the following demographic, economic, and health-care indicators on the basis of previous literature5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and we obtained data for 2008 to 2017 for all countries when available (further details of the sources of this data in the appendix): number of psychiatric beds per 100 000 individuals (data obtained from WHO Europe32 for European countries and WHO Global33 for Australia and New Zealand); health-care spending per capita in US dollars (in denominations of US$1000; data obtained from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]);34 number of psychiatric staff (psychiatrists, mental health nurses, social workers, and psychologists) per 100 000 individuals (data obtained from WHO Global); gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) in US dollars (in denominations of $1000; data obtained from the OECD);34 income inequality (measured as Gini coefficients reported by the OECD);34 absolute poverty, defined as the proportion of the population with an income of less than $5·50 per day, a threshold defined for high-middle-income countries (data obtained from the World Bank);30 relative poverty, defined as the proportion of the population with an income of less than 50% of the national median (data obtained from the OECD);34 urbanisation, measured as the proportion of the population living in urban environments (data obtained from the World Bank);30 foreign-born population, measured as the proportion of the population who were foreign born (data obtained from Eurostat35 and the OECD);34 and BAME population, measured as the proportion of the population who identify as BAME (data obtained from the European Social Survey).36

Data analysis

We calculated the annual involuntary hospitalisation rate per 100 000 individuals (when data were not already available in this form) for each country for each available year, and plotted trends in involuntary hospitalisation rate over time for each country and summarised them as the mean percentage increase in rates between available years.

We investigated the association between rates of involuntary hospitalisation and legislation by focusing on the following topics: whether the next of kin or a relative must be consulted in the involuntary hospitalisation process; whether a legal representative must be present when the decision is made to involuntarily hospitalise someone; whether treatment is required; whether a mental health professional or non-mental health professional (typically a legal authority) makes the decision to detain someone for the longest involuntary hospitalisation order; whether there is a distinction between assessment and treatment orders; the criteria for involuntary hospitalisation, including risk and not having capacity; and whether the condition is treatable. We calculated the median and interquartile range of the annual involuntary hospitalisation rate for groups of countries with and without each legislative requirement, and we compared rates of involuntary hospitalisation in groups of countries with and without each legislative characteristic using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Given that legislation varies between states in Australia, it was grouped on the basis of the most common legislative requirement among states. For example, because treatment is required in seven of eight states, Australia was grouped as requiring treatment. In Germany, Federal Civil Code applies in most topics considered. However, where state laws apply, as with Australia, grouping was based on the most common state law.

Several years of data were available from many countries for the number of beds, GDP, income inequality, absolute and relative poverty, health-care spending, urbanisation, BAME population, and foreign-born population. We investigated the associations between each of these measures and the annual involuntary hospitalisation rate using mixed-effects models, with each year of data for each country representing a datapoint (eg, the Netherlands yielded ten datapoints because 10 years of data were available). We fitted a separate linear mixed model for each explanatory variable with involuntary hospitalisation rate as the outcome and with a random effect of country to account for correlations in hospitalisation rates within countries and a random slope of the explanatory variable to allow its relationship with hospitalisation rate to differ between countries. We did not specify any parameters involving time in the model. For number of psychiatric staff, for which only 1 year of data was available, we did a simple linear regression model to assess the association with involuntary hospitalisation rate. We did all analyses with STATA (version 15).37

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Annual involuntary hospitalisation rates are presented in Table 1. Across countries, close to 20-fold variation was recorded, with the rate in the most recent year available ranging from 14·5 involuntary hospitalisations per 100 000 people in Italy to 282 per 100 000 people in Austria (median for most recent data for each country 106·4, IQR 58·5–150·9). England is slightly higher than the median, with an involuntary hospitalisation rate in 2016 of 114·1 per 100 000 people. However, the annual rate in England has risen faster over the past 10 years (mean 4·0% annual increase) than most other countries, with the exception of France, Spain, and the Netherlands. There has been an increase in the rate of involuntary hospitalisation in some other countries, including France (4·7% mean increase per year) and Australia (3·4% mean increase per year). In other countries, such as Ireland, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark, rates have been close to constant or declining.

A comparison of legislation is presented in the appendix (basic characteristics), table 2 (criteria and requirements), and table 3 (patients' rights). Although all countries provide a description of the conditions that patients must have to be hospitalised involuntarily, these conditions are typically broadly defined, such as presence of a mental disorder, psychiatric condition, or mental disability. Some countries, such as Cyprus, require severe mental illness. In many countries, distinct emergency, assessment, and treatment orders exist. However, the specifics of detention orders vary quite widely between countries, with some countries not differentiating between assessment and treatment orders and others not separating assessment and emergency orders (table 2). One of the main areas of difference between countries is in who makes the decision to involuntarily hospitalise someone, with most countries requiring a legal authority, typically a judge, to issue long-term orders. In most cases, short-term orders, such as to detain someone until a legal authority can make a decision, can be issued by a mental health professional, and in some cases the police can detain someone in an emergency until they can be examined or assessed. However, in a minority of countries, such as Italy and Greece, orders are only issued by legal or governmental authorities (table 2).

Table 2.

Legislative frameworks related to involuntary hospitalisation, by country

|

Criteria for involuntary hospitalisation |

Person able to issue an order* |

Legal requirements |

Treatment while hospitalised |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which conditions (diagnoses) are eligible? | Does the person need to pose a risk to themselves or others? | Does the person need to not have capacity? | Does the condition need to be treatable? | Legal representative must be present or consulted? | Right to repeal or tribunal? | Next of kin or nearest relative must be consulted? | Separate assessment and treatment orders? | Is treatment required? | ||

| Australia† | Mental illness (three states reviewed) or mental disorder (five states reviewed) | Yes (eight states reviewed) | NA (two states reviewed); yes (six states reviewed) | For assessment or treatment orders (three states reviewed); yes (five states reviewed) | Police (four), clinician (two), and legal authority (two; emergency order); clinician (six) and legal authority (two; assessments of short-term orders); clinician (three) and legal authority (five; treatment or long-term order) | No (eight states reviewed) | Yes (eight states reviewed) | No (five states reviewed); right to be consulted (three states reviewed) | Yes (eight states reviewed) | No (one state reviewed); yes (seven states reviewed) |

| Austria | Mental illness | Yes | NA | No | Police (emergency order); clinician (assessments or short-term order); and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No, but judge must visit the patient in hospital within 4 days | Yes | No | No | No |

| Belgium | Mental illness | Yes | NA | No | Police (emergency order); legal authority (assessments or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No, but within 10 days of the prosecutor's decision to detain, the judge visits the patient to make a final decision | Only if manifestly ill founded | Right to be informed throughout the process; right to request and end detention, and right to appeal | No | Yes, if reason for detention was treatment |

| Cyprus | Severe mental disorder | Only in relation to detention by police | NA | NA | Police (emergency order); legal authority (assessments or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Denmark | ‘Insanity’ or similar condition | No | NA | Yes, if reason for detention is treatment | Police and clinician (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Patient is consulted on whether to involve the next of kin or family | No | Yes, if reason for detention was treatment |

| England and Wales (as part of one legal jurisdiction) | Mental disorder | Yes | No | Yes, but does not apply to assessment or emergency orders | Police and clinician (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Yes, can object and can be consulted | Yes | Yes, unless admitted for assessment |

| Finland | Mental illness | Yes | NA | Yes | Clinician (assessment of short-term order); clinician and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| France | No | Yes | No | No | Clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | Judge interviews patient after admission (between days 10 and 12) | Yes | Relative can be consulted only on request | No | No |

| Germany‡ | Mental illness or mental or psychological disability (federal law); mental illness (state laws) | Yes | Yes | Yes, if reason for detention is treatment (federal law) | Police (state law in six states), clinician, and legal authority (state law in 16 states and federal law; emergency order); legal authority (federal law; assessments or short-term order); legal authority (federal law; treatment or long-term order) | Yes, in federal law; no, in state law (16 states reviewed) | Yes | Relatives can be involved in court procedure; they can also block hospitalisation if they have legal authority, through power of attorney or court order (federal law) | Yes (federal law) | No (16 states reviewed), has to be offered |

| Greece | Mental disorder | No, if patient lacks capacity; yes, otherwise | Yes, unless risk is present | Yes | Legal authority (emergency order); legal authority (assessment or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Italy | No specific diagnosis | None | No | Yes | Legal authority (emergency order); legal authority (assessment or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| New Zealand | Mental disorder | Yes | No | No, but detention can be ordered on the basis of need for treatment | Clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | Yes, a judge meets the patient | Yes | Yes, must be consulted if practicable | No | No |

| Northern Ireland | Mental disorder | Yes | No | No | Clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, if reason for detention was treatment |

| Norway | Serious mental health illness but, in practice, occurs when the ability to perceive and consider reality is affected (eg, severe eating disorders) | No, if patient lacks capacity; yes, otherwise | Yes, unless risk is present | No | Clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Portugal | Severe mental anomaly | Yes | No | Yes | Police, legal authority (emergency order); legal authority (assessment or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No, but can participate in court proceedings | No | Yes |

| Ireland | Mental disorder | Yes (either risk or capacity criterion must be met) | Yes (either risk or capacity criterion must be met) | Yes, but applies only to detention based on impaired judgement and need for treatment, and not detention based solely on risk | Police and clinician (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes, if reason for detention was treatment |

| Scotland | Mental disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes, unless it is an emergency detention | Clinician (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Yes, to consult and appeal | Yes | No |

| Spain | Mental disorder (which is not defined by law) | Yes | Yes, no capacity to make own decisions | Yes | Clinician (emergency order); legal authority (assessment or short-term order); legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Sweden | Serious mental disorder | Yes | No | Yes | Police (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Yes, consulted about care plan | No | Yes |

| Switzerland | Mental disorder or disability or severe neglect | Yes | No | Yes, in emergency for the patient's protection | Clinician (emergency order); clinician (assessment or short-term order); clinician (treatment or long-term order) | No | Yes | Yes, involved in all treatment decisions but cannot block detention or treatment | No | No |

| The Netherlands | Psychiatric disorder or intellectual disability, dementia, or memory issues | Yes | No | Yes | Police and legal authority (emergency order); legal authority (assessment or short-term order); clinician and legal authority (treatment or long-term order) | Following emergency detention authorised by mayor, the judge visits the patient to decide whether detention should continue | Yes, but the mayor's decision is not appealable | No | Yes | Yes |

NA=not applicable.

The people authorised to issue emergency orders (typically until they can be assessed), assessment or short-term orders (eg, until a court decision is made), and treatment or long-term orders, respectively.

Numbers in brackets represent the number of states or federal territories (six states and two territories reviewed).

Indicated where federal law applies, otherwise numbers in brackets represent number of states (total of 16 states).

Table 3.

The legal rights of patients

| Patients' rights* | Protection† | |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Various rights (eight states reviewed) | Various provisions in each legislation (eg, right to information), reviews by tribunals, interpreters, communication, visits, statutory statement of rights, and complaints procedures |

| Austria‡ | Advocate and information | Risk threshold is high (life or health) |

| Belgium‡ | Independent legal representation, choice of psychiatrist, information, after care, correspondence, privacy, visits, and leave of absence | The Constitution and supervision by public prosecutor of legislation |

| Cyprus‡ | Give evidence at court, appoint own representative, information, and aftercare | Mental Health Commission, a supervisory committee for the Protection of the Rights of the Mentally Ill, provides assistance with implementation of the Mental Health Law |

| Denmark‡ | Advocate, information about coercion, and appeal decision to coerce | Respecting patients' rights, standard of care, house rules of the hospital with patients' participation, treatment plan, and patients' wishes and preferences taken into account |

| England and Wales‡ | Leave of absence, after care, independent mental health advocate, and information | Next of kin's rights |

| Finland‡ | Patients' opinion to be taken into account before treatment can be ordered, information, and independent representative | Fundamental rights' care plan, court-appointed legal counsel, and legal aid |

| France‡ | Information, advocate, appeal, vote, communication, dignity, and privacy | Same rights and individual freedoms as other patients, principle of proportionality when it comes to restriction of patients' freedoms, retention of citizen's rights, reviews every 6 months by the judge |

| Germany‡ | Legal representation for court proceedings in matters of involuntary hospitalisation, 16 states have own provisions that vary slightly, but the majority include right to information, personal freedoms, visits, communication, and aftercare | 16 states have own provisions, which vary slightly, but the majority include respecting patients' dignity, data protection, privacy, least possible interference with personal freedom, self-determination, principle of proportionality with regards to restriction of patient's freedom, and Visiting Commission |

| Greece‡ | Appeal and application to stop detention | Treatment with respect, restrictions on patient's freedom can only be established by his or her state of health and his or her needs |

| Italy‡ | No restriction on civil rights during involuntary hospitalisation | Constitution |

| New Zealand | Interpreter, welfare guardian, and legal representation free of charge | Bill of Rights Act 1990, the Human Rights Act 1993 (concerning discrimination), and the Privacy Act 1993, respect of cultural identity and beliefs, information, and review |

| Northern Ireland‡ | Leave of absence, correspondence, and information | The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority |

| Norway‡ | Information, appeal, lawyer, and legal aid | The Civil Ombudsman's Prevention Unit Against Torture and Inhuman Treatment by Detention, Monitoring Norway's Compliance with the UN Torture Convention |

| Portugal‡ | Fundamental rights, legal representation, complaint procedures, appeal, right to vote in government elections, communication, and information | Monitoring Commission |

| Ireland‡ | Information, dignity, privacy, legal representation, appeal, and absence of leave | Best interests to be taken into account, and Mental Health Commission |

| Scotland‡ | Independent advocacy, named person, advanced statement of wishes, and appeal | Non-discrimination, equality, diversity, reciprocity, informal care, participation, least restrictive alternative, and benefit |

| Spain‡ | To be heard during court proceedings, legal representation, and appeal | Judge to consider second opinion of court-appointed independent physician |

| Sweden‡ | Representative and appeal | Principle of proportionality when it comes to using coercive measures |

| Switzerland‡ | Information, representative, treatment plan in consultation, patient's wishes for treatment, future treatment on discharge, and after care | Kindes und Erwachsenenschutzrecht (child and adult protection law) and the Constitution |

| The Netherlands‡ | Information, free legal representation, and after care | Free legal representation |

Rights accompanying involuntary hospitalisation (eg, right to an independent advocate or legal representation and statutory right to aftercare).

Provisions to help protect patients' human rights (based on the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights).

Parties to the European Convention on Human Rights.

In terms of grounds for involuntary hospitalisation, almost all countries allow involuntary hospitalisation on the grounds of risk of harm to self or others, and a majority of countries require that patients pose such a risk. Only Italy does not explicitly include risk as a ground for hospitalisation, with need for treatment instead being the focus. No countries require that the patient does not have insight that they have an illness, but some (eg, Spain) require that the patient does not have the capacity to make informed decisions (table 2). However, not all countries use the concept of capacity or insight in their legislation. A few countries explicitly require that the patient's condition is treatable in hospital for them to be subject to an involuntary hospitalisation order (table 2), but all countries' treatment orders have this requirement. Italy has perhaps the most distinctive legislation, where the law requires that there be an urgent need for psychiatric treatment, that appropriate treatment cannot be provided outside of hospital, and that all proposed treatment previously offered has been refused.

In all countries included in this study, the patient or their next of kin have the right to be consulted before involuntary hospitalisation and in some cases a legal representative should be present during the decision-making process if feasible. In all countries, patients have the right to appeal an involuntary hospitalisation order, typically involving a tribunal. But the grounds for appeal vary, with some countries not allowing the decisions of a judge to be appealed unless the order is manifestly ill founded or similar. The human rights of patients are becoming an increasingly important consideration; several countries are in the process of reforming legislation to improve respect for patients' rights or have recently done so. In Ireland for example, the Mental Health Act (2001) was primarily intended to improve patients' rights by introducing measures such as greater patient involvement in the involuntary hospitalisation decision-making process and by introducing tribunals. All countries subscribe to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights treaty, adopted by the UN in 1976, and all European countries subscribe to the European Convention on Human Rights (table 3). Both treaties are intended to offer protection of civil rights.

The median annual involuntary hospitalisation rates are similar between countries grouped by legislative characteristics (table 4). No evidence suggested that rates of involuntary hospitalisation were related to differences in legislation.

Table 4.

The association between involuntary hospitalisation rates and legislative topic

|

Yes |

No |

Difference in annual involuntary hospitalisation rates between groups (p value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Median annual rate of involuntary hospitalisation (IQR) | n (%) | Median annual rate of involuntary hospitalisation (IQR) | ||

| It is a requirement that the individual poses a risk to themselves or others? | 16 (76%) | 118·7 (68·5–153·4) | 5 (24%) | 78·9 (58·8–98·7) | 0·22 |

| It is a requirement that the individual does not have capacity? | 5 (24%) | 121·9 (98·4–173·0) | 16 (76%) | 104·8 (59·5–145·5) | 0·36 |

| It is a requirement that the individual's condition should be treatable? | 10 (48%) | 118·7 (78·9–151·4) | 11 (52%) | 98·7 (58·8–150·9) | 0·78 |

| Should the next of kin or nearest relative be involved in the involuntary hospitalisation process? | 8 (38%) | 104·7 (68·5–123·3) | 13 (62%) | 121·9 (58·8–151·4) | 0·61 |

| Are separate assessment and treatment orders required? | 8 (38%) | 130·9 (88·6–164·2) | 13 (62%) | 98·7 (58·8–131·1) | 0·22 |

| It is required that the individual be treated once hospitalised? | 6 (29%) | 118·7 (78·9–155·3) | 15 (71%) | 98·7 (58·8–150·9) | 0·59 |

| Must a legal representative be present? | 2 (10%) | 114·3 (73·3–155·3) | 19 (90%) | 111·0 (58·8–150·9) | 0·72 |

| Must the longest order be issued by a legal authority?* | 15 (71%) | 115·5 (73·3–155·3) | 6 (29%) | 84·9 (55·4–131·1) | 0·31 |

If a legal authority is not involved, the order is instead issued by a medical authority.

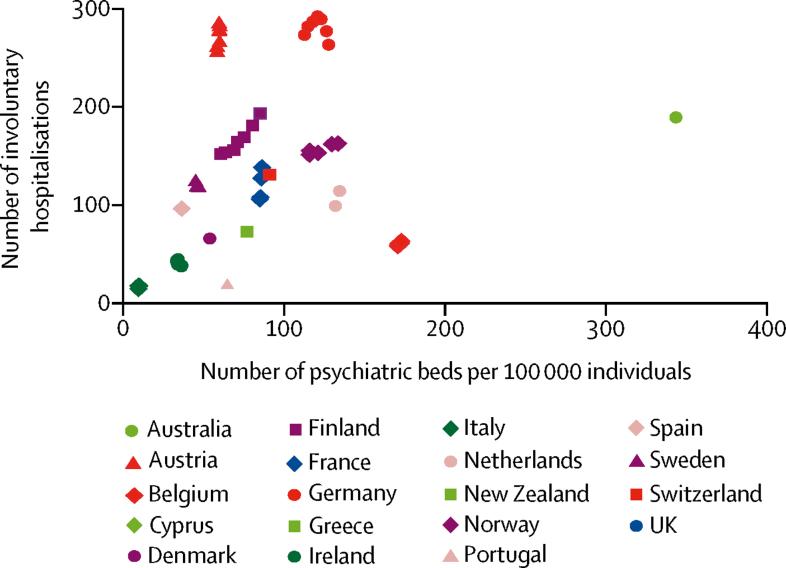

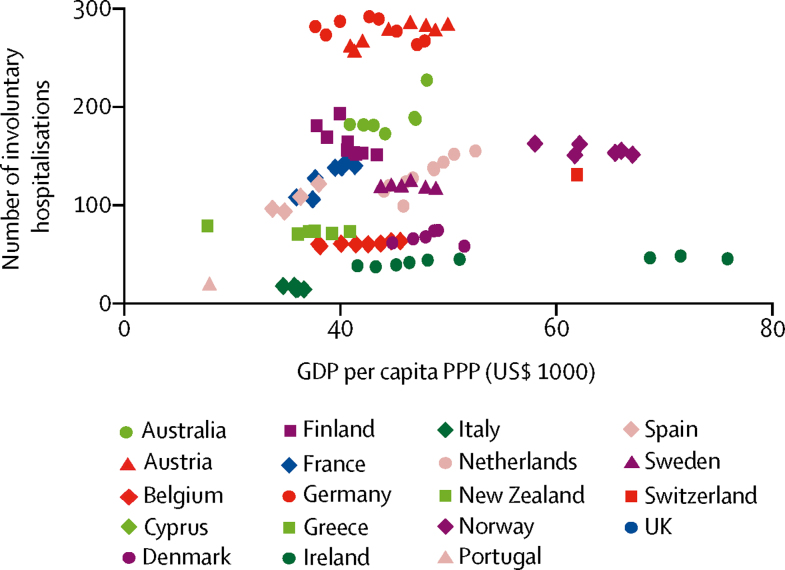

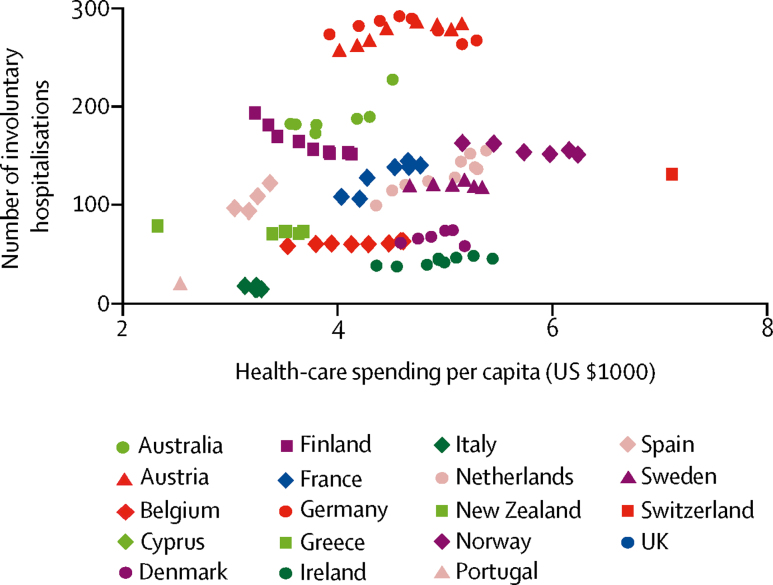

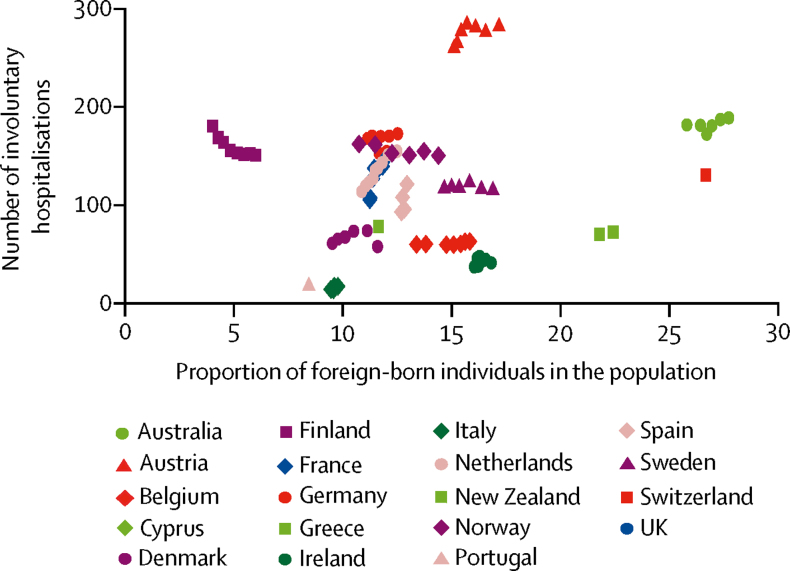

Summary statistics and estimated associations between socioeconomic and health-care factors and annual involuntary hospitalisation rates are presented (table 5). We noted weak evidence that involuntary hospitalisation rates were positively associated with provision of psychiatric beds (β coefficient 0·65, 95% CI 0·10 to 1·20, p=0·021; figure 1), GDP per capita PPP (β coefficient 1·84, 0·30 to 3·38, p=0·019; figure 2), health-care spending per capita (β coefficient 15·92, 3·34 to 28·49, p=0·013; figure 3), proportion of foreign-born individuals in a population (β coefficient 7·32, 0·44 to 14·19, p=0·037; figure 4), and inversely associated with the proportion of the population living in absolute poverty (β coefficient–11·5, −22·62 to −0·31, p=0·044; figure 5). No evidence was found of any association between annual involuntary hospitalisation rates and relative poverty, inequality, the proportion of BAME population, number of mental health clinicians, or urbanisation (table 5).

Table 5.

Association between annual involuntary hospitalisation rates and demographic, economic, and health-care provision variables, by legislative topic

|

Summary statistics |

Association with annual involuntary hospitalisation rates |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR)* | Estimate (95% CI)† | p value | |

| Inpatient psychiatric beds per 100 000 individuals | 63·8 (46·1–93·0) | 0·65 (0·10 to 1·20) | 0·021 |

| Foreign-born population | 12·7% (11·1–16·1) | 7·32% (0·44 to 14·19) | 0·037 |

| GDP per capita PPP (US$1000) | 1·7 (36·1–47·9) | 1·84 (0·30 to 3·38) | 0·019 |

| Inequality (Gini coefficient) | 0·3 (0·27–0·33) | −67·9 (−656·7 to 520·8) | 0·82 |

| Relative poverty | 0·1% (0·08–0·12) | −118·7% (−834·4 to 597·0) | 0·74 |

| Urbanisation | 79·2% (69·0–86·1) | 4·43% (−2·85 to 11·70) | 0·23 |

| Health-care spending per capita (US$1000) | 4·2 (3·25–5·97) | 15·92 (3·34 to 28·49) | 0·013 |

| Absolute poverty | 0·5% (0·20–1·20) | −11·5% (−22·6 to −0·3) | 0·044 |

| BAME population | 4·10% (3·00–5·90) | −2·79% (−8·13 to 2·55) | 0·31 |

| Mental health clinicians per 100 000 individuals | 83·7 (26·1–113·7) | 0·44 (−0·07 to 0·95) | 0·083 |

GDP=gross domestic product. PPP=purchasing power parity. BAME=black and minority ethnic.

For each measure, the mean within each country was calculated using values from each available year and then summarised across countries using the median and IQR.

Estimated change in the annual incidence of involuntary hospitalisation (per 100 000 people) per unit increase in the predictor variable.

Figure 1.

Association between psychiatric beds and involuntary hospitalisation

Figure 2.

Association between GDP per capita, PPP, and involuntary hospitalisation

GDP=gross domestic product. PPP=purchasing power parity.

Figure 3.

Association between health-care spending per capita and involuntary hospitalisation

Figure 4.

Association between proportion of foreign-born individuals and involuntary hospitalisation

Figure 5.

Association between absolute poverty and involuntary hospitalisation

Discussion

We compared annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation between 22 European countries, Australia, and New Zealand. Rates of involuntary hospitalisation varied strikingly between countries. Time trends in annual rates also differed, with rates rising in 11 of the 18 countries with multiple years of data, but staying constant or declining elsewhere. These wide variations are consistent with older literature on this topic, with rates falling within a similar range as when previously examined at the start of this century.3, 4 These findings are despite reports of the prevalence of mental disorders varying relatively little between European countries (although high-quality international comparative studies are scarce).37 Thus, these large variations do not seem to have clear relationships with any differences in clinical need. Understanding what underlies these variations, and whether they might be related to differences in legislation or variations in indicators of service provision or economic or demographic indicators is potentially helpful in illuminating the drivers of involuntary hospitalisation.

Internationally, mental health legislative frameworks differed in a few key areas, including the criteria for hospitalisation and who has the authority to issue hospitalisation orders. Italy has a relatively distinct legal system and has lower annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation than most countries (14·48 per 100 000 individuals), with only Portugal being close (18·19 per 100 000) to having such a low number of hospitalisations. It is possible that a relevant factor is Italy's unusually stringent criteria for involuntary hospitalisation, which do not include risk as a possible justification and place a strong emphasis on treatment outside of hospital. In England, a substantial proportion of both the overall number of involuntary hospitalisations and the rise in the rate of these hospitalisations over the past 10 years is attributable to the increasing use of assessment orders.1 This suggests that the difference in rates in both overall terms and the rise of involuntary hospitalisations in England might be at least partially attributable to the increasing use of shorter-term involuntary hospitalisation orders that exist in English law but not in all countries (appendix).

However, our results suggest that overall there was no clear association between legislation and rates of involtunary hospitalisation. This finding is again consistent with the results of Salize and Dressing,3 who found no evidence of an association between legislation and rates of involuntary hospitalisations. This absence of association might be at least partially due to legislative differences we considered to have a relatively minimal effect on clinical practice. For example, patients who would be hospitalised on the grounds of risk in some countries might instead be hospitalised for urgent treatment in others. Equally, not separating assessment and treatment orders might have a minimal effect on when a patient is hospitalised involuntarily if the treatment order is defined or interpreted broadly enough to allow assessment as well. Another source of variation could be that patients might sometimes be voluntarily admitted with the understanding that if they try to discharge themselves, they will be involuntarily hospitalised. Thus, voluntary hospitalisations can involve a degree of stated or unstated coercion; such practices might differ widely between countries, contributing to variation in annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation. However, this result needs to be interpreted carefully. There were some substantial, but non-significant, associations between legislative characteristics and involuntary hospitalisation (eg, regarding whether involuntary hospitalisation requires that the person poses a risk to themselves or others). A larger sample of countries might have resulted in a significant finding for one or more legislative characteristics, although the strength of these associations is not sufficient to explain much of the wide variation in rates of involuntary hospitalisation between countries.

Additionally, some evidence indicated that greater inpatient service provision (measured as the number of inpatient psychiatric beds per 100 000 individuals) was associated with higher rates of involuntary hospitalisation than lower inpatient service provision, although this association was of small magnitude. This finding would be compatible with a higher bed capacity being associated with greater use of health-care resource than lower bed capacity. Italy, a country of particular interest for its low rates of detention, has multiple potential drivers for these rates. Relatively restrictive legislation regulating involuntary hospitalisation was introduced in 1978. At the same time, public psychiatric hospitals started to be closed. Consequently, a substantial decline in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds per 100 000 individuals has occurred over the past 40 years. During that period, there has also been a significant decrease in the rates of involuntary hospitalisation.38 Reductions in bed capacity driving lower rates of involuntary hospitalisation are a potential contributor to this fall, but extensive efforts to develop community services and a culture in which deinstitutionalisation and reintegration into the community are highly valued might also be important contributors and could not be measured in our study. There was also some evidence that GDP per capita at PPP, health-care spending per capita, and the proportion of foreign-born individuals in the population were positively associated with the rate of involuntary hospitalisation, whereas the prevalence of absolute poverty was inversely associated with the annual rate of involuntary hospitalisation. However, these associations were again small. These results suggest that high-income countries with more inpatient psychiatric health-care provision and higher rates of immigration tend to have higher rates of involuntary hospitalisation. However, not all cases fit this pattern. For example, in England, psychiatric bed numbers have been declining, whereas the rates of involuntary hospitalisation have been rising.4 Thus, societal, political, or health-care-related explanations that might influence this trend in England do not apply elsewhere. Explanations of these results require further research, especially on the relationship between demographics, economics, and health-care provision, which needs to be informed by an awareness of the sociocultural and political circumstances of individual countries. People with severe mental illnesses could be to varying degrees detained in settings other than general inpatient psychiatric facilities (eg, prisons or forensic mental health settings), which might help to explain the wide variation between countries. For example, Large and Nielssen39 found an inverse relationship between the number of psychiatric beds and the number of prisoners per population across Europe. However, international studies have not replicated the finding across low-income and middle-income countries.

Our study has several limitations (further details are provided in the appendix). First, we had some problems with obtaining involuntary hospitalisation data, which might limit the generalisability of our results or introduce bias. These limitations include that some high-income countries, including Canada and the USA, do not provide national data, and so were excluded. Also, although best attempts were made to collect involuntary hospitalisation data for all 10 years for included countries, this was not always possible. Second, differences in the method by which rates of involuntary hospitalisation are calculated between countries limit comparability. These differences include that for some countries, data are available for the total number of involuntary hospitalisations, and for others, they are available for the number of involuntary hospitalisation orders issued by a court or other authority, and therefore the data from courts or other authorities could be inflated compared with the total number of hospitalisations. Similarly, involuntary hospitalisation data for Germany and Scotland include a small number of detentions in community settings. Third, in England, data for 2016–17 are believed to be unreliable because of a change between data collection methods, and so were excluded from analyses. Fourth, we focused only on western Europe and Australasia and only on a 10 year period, limiting the generalisability of our findings. Fifth, demographic and economic data were only available for the whole of the UK and not its individual member states. To include the UK in the analyses, annual involuntary hospitalisation rates for the whole of the UK were calculated by combining figures for its member countries as described in table 1. Additionally, the prevalence of absolute poverty used an income threshold of $5·50 per day. The World Bank recommends a threshold of $21·70 per day for high-income countries, but data with this threshold were not available. Thus, the prevalence of absolute poverty based on the measure we used was very low across all countries; however, we retained the measure as potentially relevant, given that people living in absolute poverty might be especially likely also to have severe mental health problems. Sixth, assessing the relationship between legislation or demographic, economic, and health-care factors and annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation is complex, and there might well be confounders or explanatory variables that we did not measure. Seventh, international trends might not reflect intranational trends. Future research could investigate the association between regional rates of involuntary hospitalisation with socioeconomic and health-care provision within a single country.7, 8 Finally, because this is an ecological study, associations found at a national level might not reflect associations at an individual patient level.

Variability in annual involuntary hospitalisation rates was large, with a 20-fold difference between the highest and lowest rates internationally. Time trends were inconsistent, with 11 countries recording a rise in rates, whereas elsewhere they remained constant or declined. Some variations in national legislative frameworks were noted, but we could not find clear evidence of an association between legislative arrangements and involuntary admission. We observed a trend towards higher annual rates of involuntary hospitalisation in higher-income countries, with more inpatient facilities tending to have higher rates, but this was a modest association with multiple potential explanations, and we were not able from the legislative, clinical, or sociodemographic variables investigated to explain much of the large variation in detention rates. Possible explanations for these large, perhaps unwarranted, variations in practice include potential variations in clinical practice, especially in relation to when hospitalising someone involuntarily is deemed appropriate and what alternatives to detention can be offered in the community or in the family, and societal responses to people with mental illness. More work to explore this topic is needed, because understanding these large variations has the potential to help the understanding of what drives involuntary hospitalisations and how they might be reduced to a clinically beneficial minimum.

Data sharing

Data are available from Mendeley Data.40

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This Article is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme. MCD was funded by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R3-12-011) to Prof Louise Howard. BL-E and SJ are funded by the UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The study was done to support the work of the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or its arm's length bodies, or other government departments. The key informants who contributed to this Article were Dr Astrid Lugtenburg, Prof Matthias Jaeger, Dr Lars Kjellin, Dr Tuula Wallsten, Prof Francisco Torres, Prof Jill Stavert, Prof Brendan Kelly, Dr Morten Svendal Hatlen, Dr Catherine Taggart, Dr Ian Soosay, Prof Dagmar Brosey, Dr Cecile Hanon, Dr Tanja Svirskis, Dr Mette Brandt-Christensen, Prof Eleni Palazidou, Dr Katharina Schoenegger, Prof Bernadette McSherry, Dr Nikos Christodoulou, Dr Luis Mendonca, Dr Rosa Molina, Dr Mario Luciano, Dr Livia De Picker, and Prof John Dawson.

Contributors

All authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. LSR, BL-E, and SJo designed the study. LSR obtained most of the involuntary hospitalisation, demographic, economic, and health-care data and the remaining data were obtained by MCD. LSR and MCD drafted the initial manuscript and drafted the final manuscript, and enlisted the assistance of experts based in the respective countries to be key informants. TZ initially drafted a legal profile for each country, and along with MCD reviewed and finalised the profiles on the basis of feedback from key informants. RJ and LSR planned and did the analyses. SJe and SB-F wrote the lived experience commentary.

Declaration of interests

MCD reports grants from the National Institutes of Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. MCD is a member of the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) Section of Psychiatry. MCD receives no compensation for this position, but as the UK representative, the Royal College of Psychiatrists pays their expenses to attend the UEMS biannual meeting. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.NHS Digital Mental Health Act Statistics, Annual Figures. 2017. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-act-statistics-annual-figures

- 2.GOV.UK Modernising the Mental Health Act. 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/762206/MHA_reviewFINAL.pdf

- 3.Salize H, Dressing H. Epidemiology of involuntary placement of mentally ill people across the European Union. Br J Psychiatr. 2004;184:163–168. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefano A, Ducci G. Involuntary admission and compulsory treatment in Europe: an overview. Int J Ment Health. 2008;37:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keown P, Weich S, Bhui KS, Scott J. Association between provision of mental illness beds and rate of involuntary admissions in the NHS in England 1988–2008: ecological study. BMJ. 2011;343:d3736. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Care Quality Commission Monitoring the Mental Health Act in 2015/16. 2016. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20161122_mhareport1516_web.pdf

- 7.Keown P, McBride O, Twigg L. Rates of voluntary and compulsory psychiatric in-patient treatment in England: an ecological study investigating associations with deprivation and demographics. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:157–161. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.171009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weich S, McBride O, Twigg L. Variation in compulsory psychiatric inpatient admission in England: a cross-classified, multilevel analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:619–626. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkler P, Krupchanka D, Roberts T. A blind spot on the global mental health map: a scoping review of 25 years' development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and eastern Europe. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:634–642. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Project atlas. 2018. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlasmnh/en/

- 11.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Mental health services in Australia, restrictive practices. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/restrictive-practicesAustria

- 12.Gesundheit Østerreich Analyse der unterbringungen nach UbG in österreich. 2015. https://goeg.at/sites/default/files/2017-10/UbG-2016_Final_0F.pdf

- 13.FOD Volksgezondheid Minimale Psychiatrische Gegevens. 2018. https://www.health.belgium.be/nl/gezondheid/organisatie-van-de-gezondheidszorg/ziekenhuizen/registratiesystemen/mpg

- 14.WHO Mental Health Atlas. 2014. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/mental_health_atlas_2014/en/

- 15.Statistical Information on Welfare and Health in Finland The National Institute for Health and Welfare. 2018. https://sotkanet.fi/sotkanet/en/haku?g=199

- 16.Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économique Les activités de l'Insee. 2018. https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/1302194

- 17.Bundesamt für Justiz. Betreuungsverfahren. 2019. https://www.bundesjustizamt.de/DE/SharedDocs/Publikationen/Justizstatistik/Betreuungsverfahren.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=14

- 18.WHO Mental health atlas. 2017. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/mental_health_atlas_2017/en/

- 19.Health Research Board Activities of Irish psychiatric units and hospitals 2017. 2018. https://www.hrb.ie/data-collections-evidence/psychiatric-admissions-and-discharges/publications/

- 20.Ministerio della Salute Rapporto salute mentale. 2016. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2731_allegato.pdf

- 21.Broer J, Mooij CF, Quak J, Mulder C. Stijging van BOPZ-maatregelen en dwangopnames in de ggz Ontwikkelingen in Nederland in de periode 2003–2017. Ned Tijdschr Geneesk. 2018;162:162–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency Agriculture and environment. 2018. https://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/public/Theme.aspx

- 23.Helsedirektoratet Kontroll av tvangsbruk i psykisk helsevern i 2015. 2016. https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/1251/Kontroll_av_tvang_2015_IS-2452-2015.pdf

- 24.Ministro de Saude Rede de referenciação hospitalar de psiquiatria e saúde mental. 2016. https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/rede-referencia%C3%A7%C3%A3o-hospitalar-psiquiatria-e-sa%C3%BAde-mental.pdf

- 25.Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland Statistical monitoring reports of mental health law in Scotland. 2018. https://www.mwcscot.org.uk/publications/statistical-monitoring-reports/

- 26.Fiscalia General del Estado Memoria de la fiscalia general del estado. 2017. https://www.fiscal.es/memorias/memoria2017/FISCALIA_SITE/index.html

- 27.Socialstyrelsen Psykiatrisk tvångsvård. 2018. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/psykiatrisktvangsvard

- 28.Schuler D, Tuch A, Buscher N, Camenzind P. Psychische gesundheit in der schweiz. 2016. https://www.obsan.admin.ch/sites/default/files/publications/2016/obsan_72_bericht_2.pdf

- 29.Government of Wales NHS Wales Statistics on hospital admissions for mental illness and learning disability. 2017. Available from: http://gov.wales/statistics-and-research/health-statistics-wales/?tab=previous&lang=en

- 30.The World Bank DataBank. 2018. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx

- 31.Office for National Statistics Population estimates. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates

- 32.WHO European Health Information Gateway. 2018. https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/

- 33.WHO Global Health Observatory data. 2017. http://www.who.int/gho/en/

- 34.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Data. 2018. https://data.oecd.org/

- 35.European Commission Eurostat. 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- 36.European Social Survey Subjective well-being, social exclusion, religion, national and ethnic identity (core-all rounds) 2018. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/themes.html?t=wellbeing

- 37.Wittchen H, Jacobi F, Rehm J. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbui C, Papola D, Saraceno B. Forty years without mental hospitals in Italy. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018;12:43. doi: 10.1186/s13033-018-0223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Large MM, Nielssen O. The Penrose hypothesis in 2004: patient and prisoner numbers are positively correlated in low-and-middle income countries but are unrelated in high-income countries. Psychol Psychother. 2009;82:113–119. doi: 10.1348/147608308X320099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendeley. Data. 2019. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/4y9tdf5xxf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from Mendeley Data.40