Abstract

Cell viability requires accurate chromosome segregation during meiosis and mitosis so that the daughter cells produced have the correct chromosome complement. In contrast, chromosome segregation errors lead to aneuploidy, a state of abnormal chromosome numbers. Further, a persistently high rate of chromosome segregation errors causes the related phenomenon of whole chromosomal instability (w-CIN). Aneuploidy and w-CIN are common characteristics of several human conditions and diseases including birth defects and cancers. Thus, methods to measure aneuploidy and w-CIN have important research applications in many areas of cell biology. In this chapter, we describe methods to measure chromosome mis-segregation rates and aneuploid cell survival with a focus on cells grown in culture; however, we also highlight methods that are amenable to primary tissue samples. Together, these methods provide a comprehensive approach to determining the frequency of aneuploidy and w-CIN in cells.

Keywords: Aneuploidy, Chromosomal instability (CIN), Chromosome mis-segregation, Lagging chromosomes, Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH)

1. Introduction

Organism and cell viability depend on faithful chromosome segregation during meiosis and mitosis to produce haploid and diploid daughter cells, respectively, with the correct chromosome complement. Chromosome segregation errors occurring during meiosis or mitosis (i.e. non-disjunction) result in the gain or loss of whole chromosomes, producing aneuploid cells. Aneuploidy is defined as a state of abnormal chromosome numbers that deviates from a multiple of the haploid complement. In addition, structural aneuploidy arises from DNA damage that causes translocations, duplications or deletions of chromosomal regions (Orr, Godek, & Compton, 2015). Whole chromosome aneuploidy and structural aneuploidy are linked as whole chromosome segregation errors can lead to DNA damage and structural rearrangements (Janssen, van der Burg, Szuhai, Kops, & Medema, 2011). Conversely, DNA damage can lead to whole chromosome segregation errors (Bakhoum, Kabeche, Murnane, Zaki, & Compton, 2014). In this chapter, we focus on quantitative methods to measure whole chromosome aneuploidy.

Chromosome segregation errors result in constitutional, constitutive, or mosaic aneuploidies (Orr et al., 2015). Constitutional aneuploidy is an abnormal karyotype that is present in all cells. Down syndrome is an example of constitutional aneuploidy that most frequently occurs due to meiotic errors and results in trisomy for chromosome 21 present in all cells of an individual with the condition (Hassold & Hunt, 2001; Orr et al., 2015). Constitutive aneuploidy is an abnormal but stable karyotype that generates a homogeneous sub-population of aneuploid cells (Orr et al., 2015). Mosaic aneuploidy is abnormal and unstable karyotypes that generate a heterogeneous sub-population of aneuploid cells (Orr et al., 2015). Mosaic aneuploidies are a consequence of whole chromosomal instability (w-CIN) that is defined by two separate but equally important steps: (1) a persistently high rate of chromosome mis-segregation coupled with (2) the propagation of aneuploid cells (Thompson, Bakhoum, & Compton, 2010). W-CIN is associated with several human diseases including mosaic variegated aneuploidy (MVA) and cancer (Orr et al., 2015). MVA is a rare human disorder with patients presenting growth problems, developmental delays, and an increased incidence of childhood cancers that is characterized by mosaic aneuploidies present in patient cells (Orr et al., 2015). Interestingly, a familial genetic study identified a cause of MVA as bi-allelic mutations in the mitotic gene BUB1B (Hanks et al., 2004). In cancer, over 90% of solid tumors are reported to be aneuploid and many also display intra-tumor karyotype heterogeneity due to w-CIN (Weaver & Cleveland, 2006). Paradoxically, in cancers, w-CIN has been shown to have both tumor suppressing and promoting effects with the different impacts being contextualized by both tissue of origin and rate of chromosome mis-segregation (Weaver, Silk, Montagna, Verdier-Pinard, & Cleveland, 2007). For example, low rates of w-CIN promote tumor formation and high rates inhibit tumor formation (Godek et al., 2016; Silk et al., 2013; Weaver et al., 2007). This example highlights the importance of using quantitative methods to measure aneuploidy and w-CIN to improve our understanding of human diseases.

The experimental methods used to measure aneuploidy and w-CIN derive from an understanding of the mechanisms generating both conditions. Accurate chromosome segregation during cell division relies on the precise temporal execution of multiple molecular pathways including the formation of a bipolar spindle structure, the correct attachment of microtubules to chromosomes, the tethering of sister chromatids together by cohesion until anaphase onset, and the physical separation of daughter cells during cytokinesis. Defects in any of these processes can result in the generation of aneuploidy and w-CIN; therefore, multiple experimental approaches are needed to comprehensively and quantitatively measure the frequency of aneuploidy and w-CIN.

In cancer cells and mouse oocytes, a common defect causing aneuploidy and w-CIN is the generation of lagging chromosomes in anaphase due to the persistence of incorrect microtubule attachments to kinetochores (k-MT) (Cheng et al., 2017; Cimini et al., 2001; Thompson & Compton, 2008). Kinetochores are macromolecular complexes that assemble at the site of centromeric chromatin on each chromosome and form the binding site for microtubules. Faithful chromosome segregation requires bi-oriented k-MT attachments with sister chromatids attached to microtubules from opposite spindle poles. In contrast, lagging chromosomes arise from the persistence of merotelic k-MT attachments that are formed when one kinetochore attaches to microtubules emanating from both spindle poles (Godek, Kabeche, & Compton, 2014). Merotelic attachments are not detected by the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) (Cimini et al., 2001), the signaling network that restrains anaphase onset until all chromosomes are attached to microtubules (Musacchio & Salmon, 2007). Importantly, merotelic attachments that persist into anaphase increase the probability of chromosome mis-segregation (Cimini et al., 2001; Thompson & Compton, 2008; 2011). In addition, defects in bipolar spindle formation contribute to k-MT attachment errors and increase the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase. During normal cell division, two centrosomes nucleate and organize bipolar spindle formation; however, supernumerary centrosomes result in the formation of multi-polar spindles. Although centrosome clustering mechanisms can correct multi-polar spindle defects, even transient multi-polar spindles have been shown to increase the frequency of merotelic k-MT attachments and lagging chromosomes in anaphase (Ganem, Godinho, & Pellman, 2009). Thus, measuring the rate of lagging chromosomes in anaphase is one method to estimate the prevalence of chromosome segregation errors. In this chapter, we describe an immunofluorescence (IF) assay to determine the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase.

Although quantifying the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase is a relatively easy and straightforward approach to measure the rate of chromosome mis-segregation, it is indirect and an estimate of the chromosome mis-segregation rate. Several other errors during cell division including the persistence of syntelic k-MT attachments with sister chromatids attached to microtubules from the same spindle pole (Thompson & Compton, 2011), the generation of unaligned chromosomes due to SAC defects and premature entry into anaphase, the precocious separation of sister chromatids due to cohesion defects, the segregation of chromosomes on multi-polar spindles in anaphase, and the formation of tetraploid cells due to cytokinesis failure can cause chromosome segregation errors in the absence of overtly lagging chromosomes (Orr et al., 2015). Thus, methods that measure the rate of chromosome mis-segregation regardless of the source of errors are required to comprehensively determine chromosome mis-segregation rates. In this chapter, we describe a procedure using fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) to directly calculate chromosome mis-segregation rates.

As stated above w-CIN requires two equally important steps: (1) a high rate of chromosome segregation errors and (2) the survival and propagation of aneuploid cells. Normal, diploid, immortalized or primary cells mis-segregate a chromosome approximately once every 100 cell divisions (Cimini, Tanzarella, & Degrassi, 1999; Thompson & Compton, 2008) but aneuploid cells have been shown to proliferate more slowly than their diploid counterparts (Torres et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2008) and to undergo durable cell cycle arrest and cease propagation (Thompson & Compton, 2010). Thus, normal cell populations maintain diploid and homogeneous karyotypes. In contrast, cells with w-CIN have heterogeneous and non-diploid karyotypes because aneuploid cells continue to proliferate (Thompson & Compton, 2008). In this chapter, we describe a method using FISH to measure aneuploid cell survival.

Overall, in the following sections, we present several detailed methods for the quantitative measurement of aneuploidy and w-CIN using immunofluorescence microscopy and fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) cytogenetic techniques. Specifically, section two describes an immunofluorescence assay to measure the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase. Section three describes a FISH assay to measure the rate of chromosome mis-segregation. Lastly, section four describes a FISH assay to measure aneuploid cell survival. The methods described are for tissue culture cells, but we highlight methods that are amenable to primary tissue samples as well.

2. Immunofluorescence Assay for Lagging Chromosomes in Anaphase

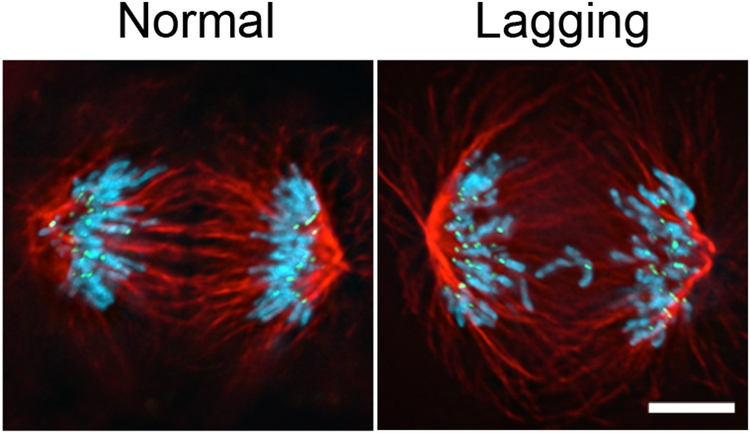

As described in the introduction, measuring the rate of lagging chromosomes in anaphase is an easy and straightforward approach to estimate the rate of chromosome mis-segregation (Figure 1). Nevertheless, this assay has several caveats including that lagging chromosomes may ultimately segregate to the correct daughter cell and that chromosome segregation errors can occur in the absence of lagging chromosomes in anaphase.

Figure 1:

Representative images of a normal anaphase or an anaphase with lagging chromosomes in U2OS cancer cells. Lagging chromosomes with a centromere are localized between the two separating nuclei. Shown in the images are DNA (blue), centromeres (green), and microtubules (red). Scale bar, 5 μm. (Reproduced from Nature Cell Biology, 2009, vol. 11, p. 28).

A. Instrumentation

This IF procedure requires an epifluorescence microscope equipped with the necessary objective and excitation and emission filters to visualize three different fluorophores. We routinely score for lagging chromosomes using a 60× 1.4NA Plan Apo oil objective as lower magnification is insufficient to visualize lagging chromosomes. Although not strictly required, it is also beneficial to have the microscope equipped with a digital camera for acquisition of representative images and computer software for image processing (Figure 1). We recommend Fiji (ImageJ) for free image processing software.

B. Cell Culture Conditions

We have successfully used this method to determine the frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase for a variety of mammalian tissue culture cells ranging from normal, diploid cells to stem cells to cancer cells from numerous tumor types (Godek et al., 2016; Thompson & Compton, 2008). There is no requirement for specific culture conditions or culture media with the exception that growth as a monolayer facilitates quantifying the frequency of lagging chromosomes. Also, we highlight that the measurement of lagging chromosomes in anaphase is not limited to cells grown in culture but also has been successfully adapted to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained tumor biopsies (Bakhoum, Danilova, Kaur, Levy, & Compton, 2011; Bakhoum et al., 2015).

C. Antibodies

The assay requires a tubulin antibody to visualize bipolar spindles and ensure that anaphase cells are scored. There are many commercially available tubulin antibodies, and we routinely use the mouse monoclonal DM1α antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). In addition, we use a centromere antibody that marks the site of microtubule attachment to chromosomes to distinguish whole chromosomes lagging in anaphase from acentric DNA fragments, which contribute to structural aneuploidies. We typically use anti-centromere antibody (ACA) serum that contains antigens to multiple different centromere epitopes and is obtained from patients with autoimmune diseases (Orr, Talje, Liu, Kwok, & Compton, 2016). However, there are commercially available centromere antibodies as well (e.g. polyclonal rabbit centromere protein-A (CENP-A) (Sigma-Aldrich).

D. Immunofluorescence

In a typical experiment, cells are seeded in culture media on 18mm round coverslips #1.5 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) at a density that will yield 70–90% confluency after overnight incubation. The next day, cells are fixed with 3.5% paraformaldehyde, pH 6.8 for 10 min at room temperature. The fixation conditions may be adjusted depending the combination of tubulin and centromere antibodies selected for use. After fixation, cells are permeabilized with 2 × 5 min washes with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and 0.1% Triton X-100. Subsequently, cells are blocked with TBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2% BSA (TBS-BSA) for 30 min. Primary antibodies are diluted in TBS-BSA to the appropriate concentration and cells are incubated for 1 hour. After incubation with primary antibodies, cells are washed 4 × 5 min TBS-BSA and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in TBS-BSA for 1 hour. We routinely use Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Life Technologies). Next, cells are washed 4 × 5 min in TBS-BSA and DNA is stained with DAPI diluted in TBS-BSA for 15 min. After DAPI staining, cells are washed 3 × 5 min TBS-BSA, 3 × 5 minutes TBS-0.1% Triton X-100, and lastly, coverslips are mounted on slides with Pro-Long Gold Anti-Fade (Life Technologies). The anti-fade is allowed to set overnight at room temperature. Slides can then be stored at room temperature for a week or sealed around the edges with nail polish (e.g. Sally Hansen Hard As Nails) and stored long-term (months) at −20°C.

E. Analysis

After completion of IF staining, anaphase cells are scored for the presence or absence of a lagging chromosome(s) (Figure 1). We define lagging chromosomes by the presence of a centromere and as being separated from the main grouping of centromeres localized near each spindle pole in anaphase. Further, this method can be used to score additional anaphase errors including acentric DNA fragments and chromatin bridges that contribute to structural aneuploidies (Godek et al., 2016). Overall, we typically score a minimum of 100 anaphases and use a two-tailed Fisher exact test to determine significant differences between experimental conditions or cell lines.

F. Alternative Method

An alternative approach to counting lagging chromosomes in fixed cells is to perform time-lapse live-cell imaging of mitotic cells. In this assay, DNA is fluorescently labeled to follow chromosomes as cells progress through mitosis. A common method to label DNA is to express fluorescently tagged histone H2B in cells (Thompson & Compton, 2008). Although this method is less straightforward than counting lagging chromosomes in fixed cells, the fluorescent labeling of DNA allows for direct visualization of lagging chromosomes in anaphase. Further, it allows for the detection of other cell division errors such as unaligned chromosomes (Thompson & Compton, 2008). For more details on live-cell imaging of mitotic cells, we refer readers to a previous published protocol (Sivakumar, Daum, & Gorbsky, 2014).

3. Chromosome Mis-segregation Assay

Although lagging chromosomes in anaphase are commonly detected in cancer cells and oocytes (Cheng et al., 2017; Thompson & Compton, 2008), other sources of cell division errors also contribute to the rate of chromosome mis-segregation (e.g. SAC defects). To directly measure chromosome mis-segregation rates regardless of the source of error, we have developed a chromosome mis-segregation assay that uses FISH α-satellite enumeration probes that are centromere specific to count chromosome copy numbers in sister cells after the completion of mitosis (Thompson & Compton, 2008).

A. Instrumentation

As described above in section 2A, this assay requires an epifluorescence microscope equipped with the necessary objective, excitation and emission filters to visualize multiple different fluorophores, a digital camera, and the capability of acquiring z-axis optical sections. In this assay, images are typically acquired as 0.25-μm optical sections with a 60× 1.4NA Plan Apo oil objective. The capability of acquiring z-axis optical sections is critical as FISH signals can be in different focal planes.

B. Cell Culture Conditions

We have performed this assay using a variety of mammalian tissue culture cells, and there is no requirement for specific culture conditions or culture media (Orr et al., 2016; Thompson & Compton, 2008).

C. FISH Probes

To determine chromosome mis-segregation rates, this assay uses α-satellite FISH enumeration probes (Cytocell) that hybridize to centromeres to count chromosome copy numbers in sister cells. The probes must be specific to a single chromosome, and we have successfully performed this assay using two differentially labeled chromosome probes simultaneously (Thompson & Compton, 2008). If performing this assay in aneuploid cells with non-diploid karyotypes, it is first necessary to determine the modal chromosome copy number for each probe being used. We also point out that this assay is feasible with cells engineered to have a fluorescently marked chromosome (e.g. LacI-GFP/LacO system) eliminating the need for α-satellite FISH probes (Orr et al., 2016).

D. Preparation of Mitotic Cells

To begin, cells are seeded in a tissue culture flask (typically T75 size). Once the culture density has reached at least 80% confluency, a mitotic shake-off is performed to collect mitotic cells. Depending on the mitotic index of the cells being studied, cells can also be treated with drugs that cause mitotic arrest, such as monastrol or nocodazole, to increase the number of mitotic cells collected. A caveat to the use of drugs that induce mitotic arrest is that these treatments will also increase chromosome mis-segregation rates due to an increase in k-MT attachment errors. The assay is best performed by testing both no treatment and drug treatment conditions. Next, mitotic cells are pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the pellet is washed with 1 x Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and subsequently the centrifugation step is repeated. The mitotic cell pellet is then resuspended in 15 ml of culture media. Following this, cells are plated at a low density in a 100 mm tissue culture dish containing a flame sterilized glass slide. The exact cell density will depend on the cells being analyzed, but the objective is to sparsely plate mitotic cells so that cells are not clumped together and individual mitotic cells can easily be distinguished. Lastly, cells are incubated at 37°C until mitosis has completed (4–14 hr). Importantly, cells are fixed prior to entrance into the next round of mitosis. At this stage, pairs of sister cells will be visible by phase contrast microscopy.

After the completion of mitosis, a glass slide is carefully removed from the 100 mm tissue culture dish (be sure to identify the side cells are on) and a slide is briefly immersed in a coplin jar containing 1 x PBS for a few seconds. Next, a slide is immersed in coplin jar containing 3:1 methanol:acetic acid fixative (always make fresh fixation solution) for 2 min. The excess methanol:acetic acid fixative is gently tapped off, and the fixation is repeated for a total of 4 × 2 min steps. After fixation, a slide is stored at room temperature for 48 hr to “age” and ensure that all fixative has evaporated. By phase contrast microscopy, the nuclei will appear gray and smooth after successful fixation.

E. FISH Procedure

After aging a slide, α-satellite FISH probes are hybridized to cells. Pre-warm in a water bath 2xSSC (20xSSC stock: 3 M NaCl, 0.3 M sodium citrate, pH 7) + 0.5% NP-40 in a coplin jar to 37°C, and then incubate a slide for 30 min in the coplin jar with the 2xSSC + 0.5% NP-40 buffer at 37°C. Next, a slide is dehydrated in 70%, 85%, and 100% ethanol for 2 min each at room temperature and then air-dried. While performing the dehydration steps, FISH probes are pre-warmed to room temperature and diluted 1:10 (the optimal dilution will depend on the FISH probe used) in the hybridization buffer that is typically supplied with the probe. The probe mixture is then pipetted onto a 22 × 22 mm square glass coverslip that is subsequently placed on top of a slide. The coverslip is sealed onto a slide by applying rubber cement around the edges of the coverslip. The rubber cement is allowed to partially dry and the slide is then placed in a hybridization cassette. We have co-opted microarray hybridization cassettes (e.g. ArrayIt hybridization cassettes for glass slides) for this step, but there are a variety of commercially available hybridization cassettes. Next, the nuclear DNA and FISH probes are denatured at 75°C for 5 min in a circulating water bath. This step can also be performed in a hybridization oven. After denaturation, a slide is incubated overnight in a pre-warmed humidified chamber at 37°C (this step can be modified to a minimum of 2 hr if required). There are two critical points at this stage in the process. First, the temperature setting in the incubator must be accurate, and second, a slide must be placed in the humidified chamber as quickly as possible to minimize the risk of cooling below 37°C. We make “homemade” humidified chambers by placing damp paper towels on the bottom of a glass Pyrex dish with parallel serological pipets placed on top to hold slides above the damp paper towels. The Pyrex dish is sealed tightly with Cling-wrap.

The next day, a coplin jar with 1 x wash buffer (0.5x SSC + 0.1% SDS) is pre-warmed to 72°C in a water bath. The temperature of the wash buffer is critical to reduce non-specific background, so we measure the temperature inside the coplin jar and do not rely on the water bath temperature setting. Also, the wash buffer temperature can be adjusted depending the specific FISH probe used. The typical range is between 70°C-74°C as above 74°C the wash conditions are too stringent and signal will be lost. Once the wash buffer has reached the appropriate temperature, a slide is removed from the humidified chamber. The rubber cement is carefully removed using forceps, the edge of the slide and coverslip are marked with a chemical resistant lab marker, and the coverslip is then removed gently with forceps. Next, a slide is immersed in the pre-warmed wash buffer. Placing a slide in the wash buffer solution will lower the temperature. Once the wash buffer has reached the desired temperature again (this may require increasing the temperature setting on the water bath), the coplin jar with the slide is removed and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Following this, a slide is transferred to a coplin jar with 1 x Phosphate-buffered detergent (PBD) (MP Biomedicals) for 2 min at room temperature. Next, a slide is incubated in 1 x PBD + DAPI for 10 min at room temperature to stain the DNA. Subsequently, a slide is briefly immersed in fresh 1 x PBD at room temperature. A new 22 × 22 mm square glass coverslip with Pro-Long Gold Anti-Fade (Life Technologies) on it is then placed on top of the slide using the markings from the previous coverslip as a guide. The anti-fade is allowed to set overnight. FISH slides can then be stored at 4°C for several weeks or at −20°C for several months.

F. Analysis

Images are acquired on an epifluorescence microscope as described in section 3A. After image acquisition, a sum intensity or maximum intensity projection (Fiji image software) is made of the acquired z-axis optical sections. The chromosome copy number is then counted for each pair of sister cells to determine if a chromosome segregated properly or mis-segregated (Figures 2A and 2B). We typically score more than 200 pairs of sister nuclei. The percent mis-segregation rates determined for individual chromosomes are then averaged to calculate an overall chromosome mis-segregation rate based on the assumption that all chromosomes have an equal probability of mis-segregating. This calculation will also require determining the modal chromosome number for a cell line (Thompson & Compton, 2008).

Figure 2:

A. Cartoon diagram showing a single chromosome FISH probe with a modal copy number of two and the expected outcomes for a normal or mis-segregation of that chromosome in sister cells. B. Representative images of a normal segregation (left panel) and chromosome mis-segregation (right panel) for MCF-7 cancer cells. Chromosome mis-segregation rates were determined using α-satellite FISH probes for chromosomes 7 (green) and 8 (red). MCF-7 cells have a mode of four copies of chromosome 7 and three copies of chromosome 8. Scale bar, 10 μm. (Reproduced from The Journal of Cell Biology, 2008, vol. 180, p. 669)

A caveat to this assay is that chromosome segregation errors may also result in a chromosome(s) contained in a micronucleus. In this assay, sister cells with micronuclei are either not scored or scored in a separate category because it cannot unambiguously be determined if micronuclei formation will result in chromosome mis-segregation. Micronuclei may be reabsorbed into the correct nucleus during the next round of mitosis.

G. Alternative Method

The chromosome mis-segregation assay described above works well with many different types of mammalian tissue culture cells (Thompson & Compton, 2008); however, we highlight an alternative method that may be more appropriate for certain cell types. For cells that survive poorly as single cells (e.g. human embryonic stem cells), a cytokinesis block assay is more likely to be a feasible approach. In brief, cells are treated with cytochalasin-B to block the completion of cytokinesis and form binucleate cells. Subsequently, using α-satellite FISH probes, chromosome copy numbers are counted in sister nuclei to determine if a chromosome segregated properly or mis-segregated. Importantly, this assay can be performed on cells growing as a monolayer on glass coverslips without the requirement of isolating mitotic cells and plating mitotic cells at low density. We refer readers to a previous published detailed protocol of this assay (Fenech, 2007).

4. Aneuploid Cell Survival Assay

For cells to have a w-CIN phenotype a high rate of chromosome mis-segregation must be coupled with the survival and propagation of aneuploid cells. For example, both CB660 normal neural stem cells and GliNS2 tumor-initiating cells have a 10–15% frequency of lagging chromosomes in anaphase; however, CB660 cells maintain a predominantly diploid karyotype because aneuploid cells do not survive and propagate while in contrast aneuploid GliNS2 cells survive leading to extensive karyotype heterogeneity (Figures 3A and B) (Godek et al., 2016). Thus, in addition to measuring chromosome mis-segregation rates, aneuploid cell survival also must be investigated to determine if cells display w-CIN. To measure aneuploid cell survival, we use α-satellite FISH probes to count chromosome copy numbers in interphase cells and calculate chromosome mode deviations (Godek et al., 2016; Thompson & Compton, 2008; 2010).

Figure 3:

A. Representative images of α-satellite FISH probes for chromosomes 2, 3, 7, and 10 for CB660 normal neural stem cells (NSC) and GliNS2 tumor-initiating cells (TICs). B. Histograms showing the distribution of chromosome copy numbers and a table showing the chromosome mode deviations. CB660 cells are normal NSCs that are predominantly diploid. In contrast, GliNS2 TICs have a significant increase in chromosome mode deviations compared to CB660 cells indicating aneuploid cell survival. *p < 0.05, Fisher exact test compared with control CB660 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (Reproduced from Cancer Discovery, 2016, vol. 6, p. 535) C. Hypothetical results for aneuploid cell survival after inducing chromosome segregation errors. Normal cells do not tolerate an aneuploid genome and do not proliferate further as shown by the return to baseline mode deviation after drug washout. In contrast, chromosomally unstable cells tolerate an aneuploid genome and continue to proliferate as shown by the continued elevation in the chromosome mode deviation after drug washout.

A. Instrumentation

As described in section 3A, an epifluorescence microscopy and accessories are required to image α-satellite FISH probes in interphase cells.

B. Cell Culture Conditions

We have performed this assay using a variety of mammalian tissue culture cells, and there is no requirement for specific culture conditions or culture media (Godek et al., 2016; Thompson & Compton, 2008; 2010). We also highlight that this assay is amenable to primary tissue samples with minor modifications (Roylance et al., 2011).

C. FISH Probes

To determine aneuploid cell survival, this assay uses α-satellite FISH enumeration probes (Cytocell) that hybridize to centromeres to count chromosome copy numbers in interphase cells. Although it is not strictly required, using FISH probes that are specific to a single chromosome facilitates performing this assay. Further, differentially labeled chromosome probes can be used simultaneously.

D. Preparation of Interphase Cells

There are two experimental approaches to assessing aneuploid cell survival. In one approach, chromosome mode deviations are determined in interphase cells with chromosome mode deviations greater than 20% indicating aneuploid cell survival (Godek et al., 2016; Thompson & Compton, 2008). A caveat to this method is that it does not distinguish between aneuploid cells that are proliferating or those that are senescent. In the second approach, cells are treated with drugs that increase chromosome mis-segregation (e.g. monastrol, nocodazole, Mps1 inhibitors), and chromosome mode deviations are determined at multiple time points following treatment. At early time points (4–48 hr) following treatment, cells will have a significant increase in chromosome mode deviations compared to their untreated modes as a proportion of cells will have gone through an error-prone mitosis but not executed apoptosis or senesced in this time period. At later time points, normal diploid cells will not have a significant increase in chromosome mode deviations compared to their baseline modes, as a sufficient time period has passed for the elimination of aneuploid cells. In contrast, chromosome mode deviations will remain significantly elevated in chromosomally unstable cells compared to their baseline mode deviations due to aneuploid cells surviving post-drug treatment (Figure 3C) (Thompson & Compton, 2010). Below we describe procedures for both approaches.

For determining chromosome mode deviations without drug treatment, cells are grown to 70–80% confluency in a tissue culture flask or dish. Typically, two confluent T75 flasks will yield a minimum of 4–5 slides at the end of the preparation. The media is aspirated from the tissue culture flasks and cells are washed with PBS. Next, cells are detached using the appropriate reagents for a particular cell type. We also point out that this protocol will work for non-adherent cells. After detachment, cells are collected in a 15 ml conical tube and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. At this point, cells from multiple tissue culture flasks can be combined. After centrifugation, the cell pellet is washed in 10 ml PBS, and the centrifugation step is repeated. The PBS is carefully aspirated, and the cell pellet is gently resuspended in residual PBS buffer by tapping the side of the tube. Next, cells are resuspended in a hypotonic solution of 5 ml 75mM KCL (always make fresh from 3M KCL stock). Initially, the 75mM KCL is added 1–4 drops at a time followed by gentle mixing (tapping the side of the tube). This is repeated until approximately 2 ml of KCL has been added. The remaining 3 ml of KCL can then be added quicker with continued mixing. The cells are incubated at 37°C for 10 min to swell nuclei. The incubation time may be adjusted depending on the cell line being used. In particular, if the incubation time in the hypotonic solution is too short, interphase cells will have excess cytoplasm remaining that will reduce the efficiency of FISH probe hybridization. After sufficient incubation at 37°C, cells are pelleted by centrifugation at 900 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. The 75mM KCL is carefully aspirated, and the cell pellet is gently resuspended in the residual 75mM KCL buffer by tapping the side of the tube. Next, cells are resuspended in 5 ml 3:1 methanol:acetic acid fixative (always make fresh fixation solution). Initially, the fixative is added 1–4 drops at a time followed by gentle mixing. This is repeated until approximately 2 ml of fixative has been added. The remaining 3 ml of fixative can then be added quicker with continued mixing. Next, cells are pelleted by centrifugation at 900 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. The fixative is carefully aspirated, and the pellet is gently resuspended in the residual fixative by tapping the side of the tube. Subsequently, the fixation is repeated by adding 2 ml additional 3:1 methanol:acetic acid to the cell pellet followed by repeating the centrifugation step. After centrifugation, approximately 1.5 ml of fixative is removed and the cell pellet is gently resuspended in the remaining ~500 μl of fixative. This volume may be adjusted depending on the number of cells collected.

While preparing cells, slides are soaked in 100% ethanol at room temperature. During the final centrifugation step, slides are rinsed extensively in water and then soaked in water. Once cells and slides are prepared, a Pasteur pipet is used to “drop” cells onto wet slides. To do this, hold a wet slide at a ~45° angle and drop 3–5 drops across the top surface allowing the drops to run down the slide and displace the water. Quickly dry off the edges and underside of a slide to prevent water from running across cells. Keep the slide at an angle and allow to air dry. After this, cells fixed to the slide can be viewed by phase contrast microscopy. Nuclei that are well fixed will appear dark gray with little cytoplasm remaining. Lastly, a slide is stored at room temperature for 48 hr to “age”.

The procedure is similar for determining chromosome mode deviations after treatment with drugs that induce chromosome mis-segregation errors. To begin, cells are grown to 70–80% confluency in a tissue culture flask. Cells are then treated with drugs that increase chromosome segregation errors. The exact duration of treatment will depend on the drug used to induce errors with the goal having most cells go through at least one round of mitosis in the presence of drug. After treatment, the drug is washed out and fresh media is added to cells. Following this, cells are allowed to continue to proliferate in culture without further treatment until collected and prepared as described above. If the drug treatment also arrests cells in mitosis, a mitotic shake-off is performed to collect mitotic cells and washout the drug. After shake-off, mitotic cells are plated in fresh media and allowed to proliferate in culture without further treatment until collected and prepared as described above.

E. FISH Procedure

The FISH procedure is the same protocol detailed in section 3E. However, if after fixation and aging of cells, excess cytoplasm remains the following protocol can be performed prior to FISH probe hybridization. Pre-warm in a water bath 2xSSC in a coplin jar to 37°C, and then incubate a slide for 2 min. After this, incubate a slide in a coplin jar with 0.005% pepsin in a buffer of 0.01 M HCL at 37°C for 10 min. A stock solution of 5% pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich) is prepared in water and aliquots are stored at −20°C. The incubation time in pepsin can range from 5–15 min depending on the amount of cytoplasm remaining. After pepsin treatment, wash a slide in PBS for 3 min at room temperature. Next, post-fix a slide in 1% buffered formaldehyde in PBS and 20mM MgCl2 for 10 min at room temperature. Following this, wash again in PBS for 3 min at room temperature. After this step, the FISH protocol described in section 3E is followed starting with the ethanol washes to dehydrate cells.

F. Analysis

Images are acquired on an epifluorescence microscope as described in section 3A. After image acquisition, a sum intensity or maximum intensity projection (Fiji image software) is made of the acquired z-axis optical sections. The chromosome copy number is then counted in nuclei (Figure 3A), and we typically score more than several hundred interphase nuclei. From the data collected, the percent chromosome mode deviation is calculated and significant differences between cell lines or time points is determined by a two-tailed Fisher exact test.

G. Alternative Method

The use of α-satellite FISH probes is advantageous for statistical power because the sample size is hundreds of single cells, but it is limited in the number of chromosome probes that can be analyzed simultaneously. An alternative approach is to perform spectral karyotyping (SKY) to determine the copy numbers of all chromosomes in a single cell and measure the chromosome mode deviations (Godek et al., 2016); however, this approach is limited by need for specialized instrumentation and expense. We refer readers to a published protocol for details on performing SKY karyotyping (Padilla-Nash, Barenboim-Stapleton, Difilippantonio, & Ried, 2006).

5. Concluding Remarks

In summary, the protocols detailed in this chapter describe how to measure both aneuploidy and w-CIN in cells. Furthermore, these methods can be applied to many cell types and adapted for primary tissue samples facilitating their use in many research applications. Importantly, these methods are quantitative, thus allowing for investigations into the causes and consequences of the rate of chromosome mis-segregation on normal and diseased cell physiology. In the future, we anticipate that single-cell genomic DNA sequencing to determine chromosome copy numbers will be added to this toolkit as the technology becomes routine and less expensive.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank current and past members of the lab, and in particular, Sarah Thompson, Samuel Bakhoum, Bernardo Orr, and Christopher Laucius whose extensive efforts contributed to the development and refinement of these methods. This work has been supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37GM051542 to D.A. Compton.

References

- Bakhoum SF, Danilova OV, Kaur P, Levy NB, & Compton DA (2011). Chromosomal instability substantiates poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clinical Cancer Research : an Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 17(24), 7704–7711. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhoum SF, Kabeche L, Murnane JP, Zaki BI, & Compton DA (2014). DNA-damage response during mitosis induces whole-chromosome missegregation. Cancer Discovery, 4(11), 1281–1289. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhoum SF, Kabeche L, Wood MD, Laucius CD, Qu D, Laughney AM, et al. (2015). Numerical chromosomal instability mediates susceptibility to radiation treatment. Nature Communications, 6, 5990 10.1038/ncomms6990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J-M, Li J, Tang J-X, Hao X-X, Wang Z-P, Sun T-C, et al. (2017). Merotelic kinetochore attachment in oocyte meiosis II causes sister chromatids segregation errors in aged mice. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex), 16(15), 1404–1413. 10.1080/15384101.2017.1327488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D, Howell B, Maddox P, Khodjakov A, Degrassi F, & Salmon ED (2001). Merotelic kinetochore orientation is a major mechanism of aneuploidy in mitotic mammalian tissue cells. The Journal of Cell Biology, 153(3), 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimini D, Tanzarella C, & Degrassi F (1999). Differences in malsegregation rates obtained by scoring ana-telophases or binucleate cells. Mutagenesis, 14(6), 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M (2007). Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay. Nature Protocols, 2(5), 1084–1104. 10.1038/nprot.2007.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, & Pellman D (2009). A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature, 460(7252), 278–282. 10.1038/nature08136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godek KM, Kabeche L, & Compton DA (2014). PERSPECTIVES. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 16(1), 57–64. 10.1038/nrm3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godek KM, Venere M, Wu Q, Mills KD, Hickey WF, Rich JN, & Compton DA (2016). Chromosomal Instability Affects the Tumorigenicity of Glioblastoma Tumor-Initiating Cells. Cancer Discovery, 6(5), 532–545. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S, Coleman K, Reid S, Plaja A, Firth H, Fitzpatrick D, et al. (2004). Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition caused by biallelic mutations in BUB1B. Nature Genetics, 36(11), 1159–1161. 10.1038/ng1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T, & Hunt P (2001). To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2(4), 280–291. 10.1038/35066065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen A, van der Burg M, Szuhai K, Kops GJPL, & Medema RH (2011). Chromosome segregation errors as a cause of DNA damage and structural chromosome aberrations. Science (New York, NY), 333(6051), 1895–1898. 10.1126/science.1210214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, & Salmon ED (2007). The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8(5), 379–393. 10.1038/nrm2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr B, Godek KM, & Compton D (2015). Aneuploidy. Current Biology : CB, 25(13), R538–R542. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr B, Talje L, Liu Z, Kwok BH, & Compton DA (2016). Adaptive Resistance to an Inhibitor of Chromosomal Instability in Human Cancer Cells. CellReports, 17(7), 1755–1763. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Nash HM, Barenboim-Stapleton L, Difilippantonio MJ, & Ried T (2006). Spectral karyotyping analysis of human and mouse chromosomes. Nature Protocols, 1(6), 3129–3142. 10.1038/nprot.2006.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roylance R, Endesfelder D, Gorman P, Burrell RA, Sander J, Tomlinson I, et al. (2011). Relationship of Extreme Chromosomal Instability with Long-term Survival in a Retrospective Analysis of Primary Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 20(10), 2183–2194. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk AD, Zasadil LM, Holland AJ, Vitre B, Cleveland DW, & Weaver BA (2013). Chromosome missegregation rate predicts whether aneuploidy will promote or suppress tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(44), E4134–41. 10.1073/pnas.1317042110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar S, Daum JR, & Gorbsky GJ (2014). Live-cell fluorescence imaging for phenotypic analysis of mitosis. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 1170, 549–562. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0888-2_31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, & Compton DA (2008). Examining the link between chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in human cells. The Journal of Cell Biology, 180(4), 665–672. 10.1083/jcb.200712029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, & Compton DA (2010). Proliferation of aneuploid human cells is limited by a p53-dependent mechanism. The Journal of Cell Biology, 188(3), 369–381. 10.1083/jcb.200905057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, & Compton DA (2011). Chromosome missegregation in human cells arises through specific types of kinetochore-microtubule attachment errors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(44), 17974–17978. 10.1073/pnas.1109720108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, Bakhoum SF, & Compton DA (2010). Mechanisms of chromosomal instability. Current Biology : CB, 20(6), R285–95. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres EM, Sokolsky T, Tucker CM, Chan LY, Boselli M, Dunham MJ, & Amon A (2007). Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science (New York, NY), 317(5840), 916–924. 10.1126/science.1142210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BAA, & Cleveland DW (2006). Does aneuploidy cause cancer? Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 18(6), 658–667. 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BAA, Silk AD, Montagna C, Verdier-Pinard P, & Cleveland DW (2007). Aneuploidy acts both oncogenically and as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell, 11(1), 25–36. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR, Prabhu VR, Hunter KE, Glazier CM, Whittaker CA, Housman DE, & Amon A (2008). Aneuploidy affects proliferation and spontaneous immortalization in mammalian cells. Science (New York, NY), 322(5902), 703–709. 10.1126/science.1160058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]