Abstract

Objective:

To examine the prognostic value of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and fluorothymidine (FLT) interim positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Methods:

44 patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL underwent both fluorine 18 FDG (18F-FDG) and 18F-FLT PET/CT scans at baseline and after two cycles of a rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimen. Maximum standard uptake values (SUVmax) and changes in SUV (ΔSUV) were calculated for both tracers for the predominant lesion of each patient, for prediction of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results:

The median follow-up period was 71 months. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis indicated that the best ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (ΔSUVFDG) and FLT (ΔSUVFLT) were 79 and 76%, respectively. A ΔSUVFLT cut-off of 76% had the highest significance for prediction of PFS (p = 0.003) and OS (p = 0009), with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 80.0, 85.7, and 81.8% respectively in response assessment.

Conclusion:

Interim FLT PET/CT had higher specificity and accuracy than standard FDG PET/CT-based interpretation.

Advances in knowledge:

This study demonstrated that interim FLT PET/CT had higher accuracy than standardized FDG-based interpretation for therapeutic response assessment in DLBCL. FLT had the advantage of potentially reducing false positive of interim FDG PET/CT.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common and aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and should be immediately diagnosed and treated. Conventional chemotherapy has been shown to be effective in only 60% of patients. Approximately 30–40% of patients eventually relapse or are primary refractory and fail to achieve complete response (CR).1, 2 Positron emission tomography/CT(PET/CT) with the radioactive tracer fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) is the most common and non-invasive imaging technique for staging, restaging, monitoring, and predicting the prognosis of DLBCL. Over the past decade, interim FDG PET/CT after two to four cycles of chemotherapy has been reported to be a powerful tool for differentiating responding from non-responding patients with DLBCL.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the potential prognostic value of interim FDG PET/CT, utilizing measures including the maximum (mean) standardized uptake value [SUVmax(mean)], ΔSUVmax, metabolic tumor volume, and total lesion glycolysis.3–5 These interim PET/CT indexes have been compared with the International Prognostic Index (IPI),6 which is a widely accepted clinical prognostic index for patients with aggressive lymphomas. The correlation between SUV and IPI may indicate pretreatment FDG uptake as a metabolic marker for the prognosis of DLBCL patients. In an effort to highlight the role of interim PET/CT, the 2009 International Workshop on Interim PET in Lymphoma7 reached a consensus and recommended a 5-point visual assessment scale (the workshop was held in Deauville, and the scale is also called the “Deauville scale”, while a later workshop was held in Lugano, and the term “Lugano classification criteria” is also used)8 for clinical use. However, although interim FDG PET/CT has an excellent negative predictive value (NPV), it has a relatively low to modest positive predictive value (PPV).9 This indicates that FDG PET/CT may be suboptimal for monitoring and predicting DLBCL. Fluorine-18-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT) has been recognized as a marker of cellular proliferation, and is less affected by inflammatory changes than FDG. It has been demonstrated that FLT uptake in both solid tumors and lymphoma correlates with cell proliferation, and that FLT PET/CT allows non-invasive tumor grading and early response assessment in lymphoma.10, 11

Therefore, we prospectively investigated associations between the IPI and the two imaging modalities (FDG and FLT PET/CT) in DLBCL patients, using the standards of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). The research aims were to explore and evaluate the prognostic value of the two tracers in interim PET/CT of DLBCL patients.

Methods and materials/patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to the study.

Patients

From September 2008 to June 2010, 44 patients were enrolled in this prospective study, with the observation period running from September 2008 to February 2016. The patient inclusion criteria were: de novo pathologically proven DLBCL; first-line chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP); FDG and FLT PET/CT scans before and after two cycles of chemotherapy; and availability of images in digital format for review. The exclusion criteria were: a history of follicular lymphoma having transformed into DLBCL and/or another malignant disease, surgical excision of primary lesions, and palliative treatment (only radiotherapy or rituximab).

All patients received six cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy, with the cycles being given 21 days apart. Patients experiencing relapse were treated with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, aracytine, cisplatin) or R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, etoposide, carboplatin) as a second line therapy.

PET/CT scans

All patients underwent 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG PET/CT scans within a 3-day period, with the acquisitions being made both before (PET0) and after two cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (PET2). The time points for the FDG and FLT PET2 scans were as close as possible to the beginning of the third cycle of chemotherapy. PET/CT imaging was performed using a GE Discovery VCT PET/CT (volume CT positron emission tomography/CT) scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), with a 55 mAs tube current and 120 kV tube voltage. Patients fasted for at least 6 h prior to tracer injection. The scan commenced 60 min after i.v. administration of the tracer (0.10 mCi/kg, for both FDG and FLT). For the PET emission scan, the brain and the whole body from neck to pelvis were scanned, with five to six bed positions being used, at 3 min per bed position. Fused images were reviewed on a workstation integrated with a picture archiving and communication system (PACS; AW Suite v. 4.2, GE Healthcare).

PET/CT data analysis

All PET/CT scans were evaluated in consensus by two nuclear medicine physicians, and were assessed semi-quantitatively using regions of interest. Circular regions of interest with a diameter of 1–1.5 cm were placed on regions of the CT images corresponding to lesions. The SUVmax of the lesion with the most intense radiotracer uptake (in patients with multiple lesions) and the percentage decrease in SUVmax between the PET0 and PET2 acquisitions were measured. If residual tumor was present on the PET2 images, the SUVmax was measured on the most intense focus, even though this location may have differed from the most intense tumor on the PET0 image. In images where no lesions were identifiable, the SUVmax was measured in the area of the most intense uptake on the baseline images. For skeletal lesions in FLT PET/CT images, the SUVmax at the site where the abnormality was visible on the baseline FDG PET/CT image was measured, as the FLT images demonstrated relatively high background bone uptake. The percentage decreases in the SUVmax of FDG and FLT between the PET0 and PET2 scans (ΔSUVmax) were then calculated as ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT respectively. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to obtain suitable cut-off points for ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT. A value of 66% ΔSUVFDG was also selected as a reference cut-off value, according to reports in previous studies.11, 12 A cut-off value of 66% ΔSUVFLT was also used as a contrast control index, as there were no appropriate studies to refer to for FLT.

Additionally, all FDG PET/CT scans were analyzed according to the Deauville scale (5-point scale), and a purely visual comparison of the PET2 scans and PET0 scans was also performed: score of 1, no residual uptake; score of 2, uptake in lesion is lower than that of mediastinum; score of 3, uptake in lesion is higher than that of mediastinum, but lower than that of the liver; score of 4, uptake of lesion is moderately higher than that of the liver; score of 5, uptake of lesion is markedly higher than that of the liver and/or new lesions. Scores of 4 or 5 were classified as positive and scores of 1–3 were classified as negative.

Statistical analysis

OS was defined as the time from the start of chemotherapy to the time of death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time from the start of chemotherapy to the time of relapse or death. The prognostic value of interim PET/CT, including the indexes of the Deauville 5-point scale (for FDG studies), ΔSUVFDG, and ΔSUVFLT, were assessed by survival curves obtained using Kaplan-Meier estimates and comparisons using the log-rank test. Differences in sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were compared using the diagnostic test. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard regression model for different ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT cut-off values and IPI scores. Differences were considered significant when the p value was <0.05. SPSS v. 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patients and characteristics

The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median follow-up period was 71 months. According to the International Harmonization Project criteria, the follow-up data at the end of treatment revealed 30 patients with a complete response (CR), 5 patients with progressive disease, 8 patients with a partial response, and 1 patient with stable disease. By the end of follow-up, 13 patients had died after a median delay of 8 months (3–55 months), and 3 patients (among 30 CR patients) had relapsed, which was defined as the return of disease after achieving and maintaining CR.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients

| Characteristic | Data |

| Age (mean ± standard deviations) | 52.0 ± 15.6 (18–77) |

| No. of male patients | 25 (56.8%) |

| No. of female patients | 19(43.2%) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |

| I-II | 17 (38.6%) |

| III-IV | 27 (61.4%) |

| IPI | |

| Low risk (0–1) | 20 (45.4%) |

| Low-intermediate risk (2) | 15 (34.1%) |

| High-intermediate risk (3) | 4 (9.1%) |

| High risk (4–5) | 5 (11.4%) |

| B symptoms | |

| Positive | 21 (47.7%) |

| Negative | 23 (52.3%) |

| Germinal center (GC) | |

| GC | 11 (25.0%) |

| Non-GC | 33 (75.0%) |

IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Measurement of SUVmax and ΔSUVFDG/ΔSUVFLT cut-off values

After two cycles of treatment, both the FDG and FLT SUVmax values of the lesions were significantly lower than at baseline. In the reference regions, including mediastinum, liver, and bone marrow, uptake on the interim FDG scan was slightly increased above that at baseline. Only bone marrow uptake showed a decrease on the interim FLT scan. The SUVmax measurements are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

SUVmax parameters at baseline and interim FDG and FLT PET/CT

| SUVmax | Baseline | Interim | p Value |

| FDG | |||

| Lymphoma lesions | 14.4 ± 8.3 (3.1–45.0) | 3.5 ± 3.5 (1.0–17.5) | 0.000 |

| Reference regions | |||

| Mediastinum | 1.7 ± 0.4 (0.8–2.4) | 1.8 ± 0.3 (1.0–2.3) | 0.001 |

| Liver | 2.2 ± 0.5 (1.5–3.9) | 2.5 ± 0.4 (1.4–3.3) | 0.000 |

| Bone marrow | 2.4 ± 0.5 (1.6–3.9) | 2.1 ± 0.5 (0.9–4.1) | 0.001 |

| FLT | |||

| Lymphoma lesions | 8.4±5.8 (1.5-28.0) | 1.7±1.3 (0.4-5.5) | 0.000 |

| Reference regions | |||

| Mediastinum | 0.6 ± 0.2 (0.3–1.0) | 0.6 ± 0.1 (0.4–1.0) | 0.210 |

| Liver | 5.1 ± 1.2 (2.8–7.7) | 5.4 ± 0.9 (3.2–7.0) | 0.056 |

| Bone marrow | 9.0 ± 2.7 (2.7–15.0) | 7.8 ± 1.5 (3.9–10.0) | 0.000 |

FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; FLT, fluorothymidine; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/CT; SUVmax, maximum standard uptake value.

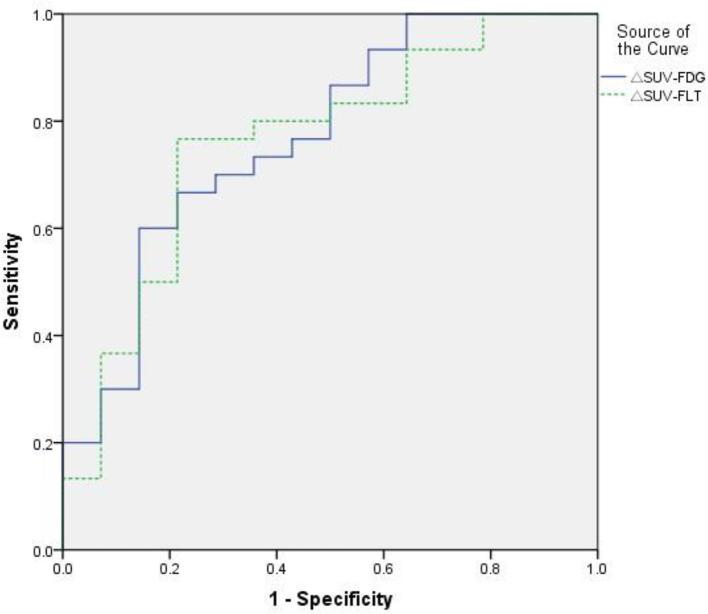

ROC curve analysis was used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) and the ideal cut-off value for distinguishing the low ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT groups from the high ones. The AUC was 0.769 for ΔSUVFDG [p = 0.004; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.615–0.923] and 0.762 for ΔSUVFLT (p = 0.006; 95% CI 0.605–0.918; Figure 1). The ideal cut-off values were obtained by choosing the maximum of the Youden index, to achieve a reasonable balance of sensitivity and specificity. A value of 79% for ΔSUVFDG achieved a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity of 78.6%, while a value of 76% for ΔSUVFLT achieved a sensitivity of 76.7% and a specificity of 78.6%.

Figure 1.

ROC analysis of ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT in the prediction of complete remission in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. The areas under the curves of ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT were 0.769 and 0.762 respectively. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SUV, standard uptake value; ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose); ΔSUVFLT, ΔSUV cut-off values for FLT (fluorothymidine).

Clinical outcome prediction by interim PET/CT using visual (Deauville scale) and semi-quantitative assessment (ΔSUV cut-off criteria)

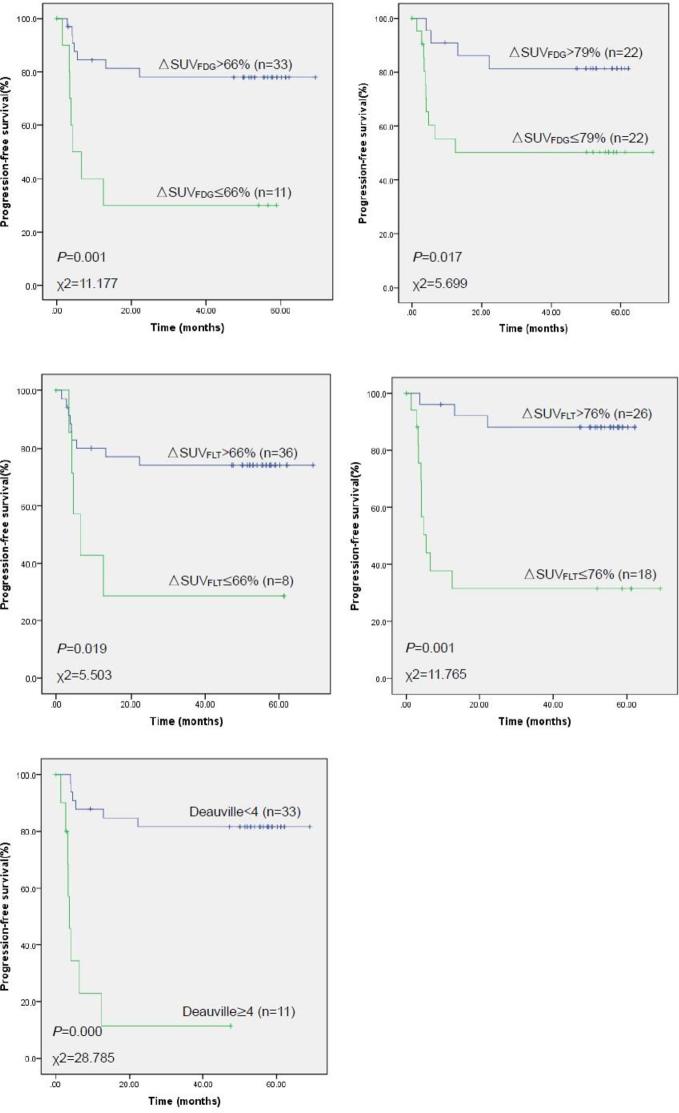

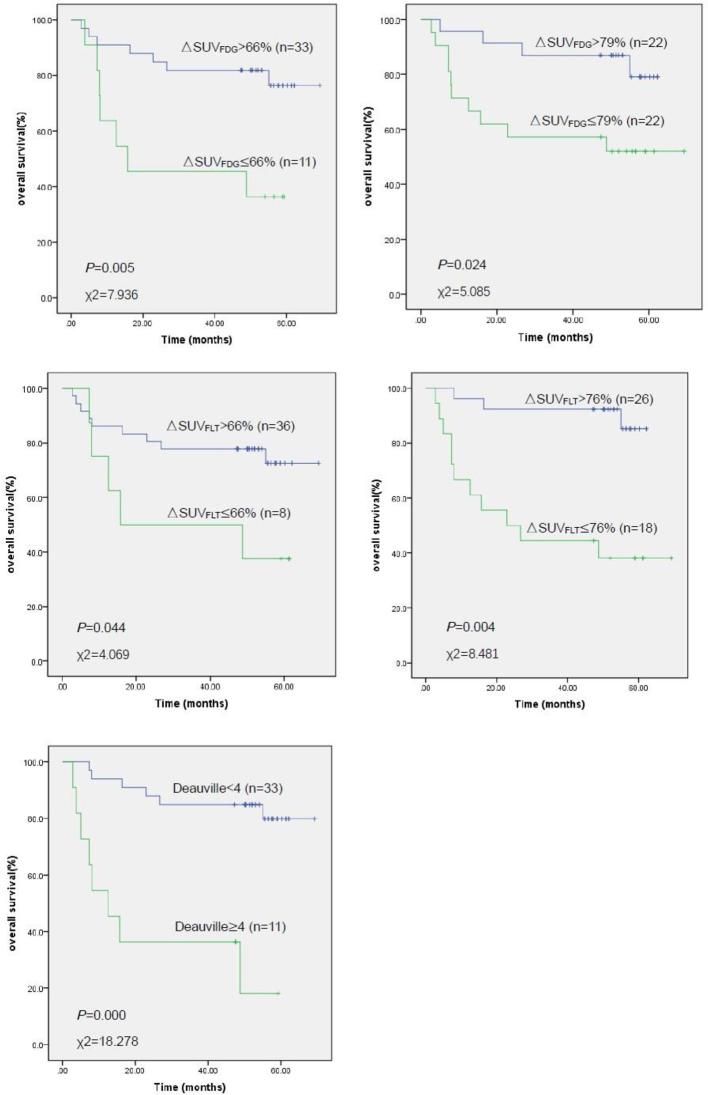

Of the 44 patients with interim FDG PET/CT scans, 10 patients were scored as 1, 17 were scored as 2, 6 were scored as 3, 8 were scored as 4, and 3 were scored as 5. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates demonstrated a significant difference (p < 0.001) in PFS and OS between the low (a score of 1–3) and high scores (a score of 4–5). 3-year PFS rates were 81.6% for a score of 1–3 (95% CI 68.3–94.9%), and 11.4% for a score of 4–5 (95% CI 0–32.4%). OS rates were 84.8% for a score of 1–3 (95% CI 72.6–97.0%), and 36.4% for a score of 4–5 (95% CI 8.0–64.8%).

In terms of semi-quantitative assessment for survival estimates, both tracers and both ΔSUV cut-off values (the recommended value of 66% established in previous studies and our optimal ΔSUV cut-offs of 79% for FDG and 76% for FLT, as obtained from the ROC curves) revealed significant differences in PFS and OS between the low and high levels. The 66% ΔSUVFDG cut-off and 76% ΔSUVFLT cut-off were highly predictive of PFS (p = 0.001). 3-year PFS rates were 78.0% (95% CI 63.5–92.5%) for ΔSUVFDG > 66%, 30.0% (95% CI 1.6–58.4%) for ΔSUVFDG < 66%, 88.1% (95% CI 75.6–94.2%) for ΔSUVFLT > 76%, and 31.5% (95% CI 8.8–54.2%) for ΔSUVFLT < 76%. These two semi-quantitative indexes also predicted highly significant differences in OS (p = 0.005 for ΔSUVFDG, p = 0.004 for ΔSUVFLT; Figures 2 and 3). OS rates were 81.8% (95% CI 68.7–94.9%) for ΔSUVFDG > 66%, 45.5% (95% CI 16.1–74.9%) for ΔSUVFDG < 66%, 92.3% (95% CI 82.1–100.0%) for ΔSUVFLT > 76%, and 44.4% (95% CI 21.5–67.3%) for ΔSUVFLT < 76%.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression free survival stratified by different cut-off values for ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUVFLT, and the Deauville scale. SUV, standard uptake value; ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose); ΔSUVFLT, ΔSUV cut-off values for FLT (fluorothymidine).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival stratified by different cut-off values for ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUVFLT, and the Deauville scale. SUV, standard uptake value; ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose); ΔSUVFLT, ΔSUV cut-off values for FLT (fluorothymidine).

Diagnostic accuracy of Deauville scale and Δsuv cut-off for response assessment

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of the Deauville scale, and the percentage change in SUV of interim FDG and FLT PET/CT are presented in Table 3. A ΔSUVFLT change of 76% showed the highest specificity (85.7%), NPV (92.3%), and accuracy (81.8%) amongst the visual and semi-quantitative assessment parameters. The Deauville scale demonstrated a similar accuracy (79.5%) to the ΔSUVFLT 76% index, with both being statistically higher than the other semi-quantitative parameters.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of different △SUVFDG, △SUVFLT, and Deauville scale cut-off values for response assessment

| Criteria | PET Negative |

PET Positive |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

Accuracy (%) |

| △SUVFDG >66% | 86.7 | 50.0 | 63.6 | 78.8 | 75.0 | ||

| CR (n = 30) | 26 | 4 | [0.745,0.989]a | [0.238, 0.762] | [0.352, 0.920] | [0.649, 0.927] | [0.540, 0.878] |

| RD (n = 14) | 7 | 7 | |||||

| △SUVFDG >79% | 63.3 | 78.6 | 50.0 | 86.4 | 68.2 | ||

| CR (n = 30) | 19 | 11 | [0.461, 0.805] | [0.571–1.001] | [0.291, 0.709] | [0.721, 1.007] | [0.544, 0.829] |

| RD (n = 14) | 3 | 11 | |||||

| △SUVFLT > 66% | 90.0 | 35.7 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 72.7 | ||

| CR (n = 30) | 27 | 3 | [0.793, 1.007] | [0.106, 0.608] | [0.290, 0.960] | [0.609, 0.891] | [0.595, 0.859] |

| RD (n = 14) | 9 | 5 | |||||

| △SUVFLT > 76% | 80.0 | 85.7 | 66.7 | 92.3 | 81.8 | ||

| CR (n = 30) | 24 | 6 | [0.657, 0.943] | [0.674, 1.040] | [0.556, 0.778] | [0.821, 1.025] | [0.704, 0.932] |

| RD (n = 14) | 2 | 12 | |||||

| Deauville | 86.7 | 64.3 | 69.2 | 83.9 | 79.5 | ||

| CR (n = 30) | 26 | 4 | [0.745, 0.989] | [0.392, 0.895] | [0.564, 0.820] | [0.704, 0.974] | [0.676, 0.914] |

| RD (n = 14) | 5 | 9 |

CR, complete response; NPV, negative predictive value; PET, positron emission tomography; PPV, positive predictive value; RD, residual disease; SUV, standard uptake value; ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose); ΔSUVFLT, ΔSUV cut-off values for FLT (fluorothymidine).

95% confidence interval (CI).

Outcome prediction for PET/CT ΔSUV value and clinical IPI score

Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazard model was performed on different ΔSUV cut-off values and IPI scores to make comparisons between PET/CT and clinical factors. Among the semi-quantitative PET/CT criteria, a ΔSUVFLT ≤ 76% predicted a poor prognosis for both PFS and OS [PFS: hazard ratio (HR) = 15.417, 95% CI 2.511–94.649, p = 0.003; OS: HR = 9.264, 95% CI 1.750–49.043, p = 0.009). The ΔSUVFDG ≤ 66% criterion demonstrated a difference that was approaching statistical significance (p = 0.058). High clinical IPI scores were also predictive of poor survival (PFS: HR = 2.376, 95% CI 1.314–4.297, p = 0.004; OS: HR = 1.792, 95% CI 1.047–3.067, p = 0.033; Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of ΔSUV of PET/CT and clinical IPI scores as prognostic factors

| Progression | Free survival | Overall | Survival | |||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| △SUVFDG ≤ 66% | 4.252 | 0.954–18.961 | 0.058 | 3.259 | 0.706–15.050 | 0.130 |

| △SUVFDG ≤79% | 1.979 | 0.284–13.789 | 0.491 | 1.110 | 0.174–7.079 | 0.912 |

| △SUVFLT ≤ 66% | 0.429 | 0.109–1.684 | 0.225 | 0.489 | 0.126–1.899 | 0.301 |

| △SUVFLT ≤ 76% | 15.417 | 2.511–94.649 | 0.003 | 9.264 | 1.750–49.043 | 0.009 |

| High IPI score (3-5) | 2.376 | 1.314–4.297 | 0.004 | 1.792 | 1.047–3.067 | 0.033 |

HR, hazard ratio; IPI, International Prognostic Index; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/CT; SUV, standard uptake value; ΔSUVFDG, ΔSUV cut-off values for FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose); ΔSUVFLT, ΔSUV cut-off values for FLT (fluorothymidine).

Discussion

PET/CT has been used as a non-invasive imaging technique for staging, restaging, monitoring, and predicting the prognosis of DLBCL, especially using FDG as the radiotracer. As in the imaging of other carcinomas, researchers have been developing alternative radiotracers with higher tumor specificity than FDG. FLT has been recognized as a histopathological marker of tumor cell proliferation, and is less affected by the inflammatory responses of cells. We therefore conducted this prospective investigation to evaluate the performance characteristics of interim FDG and FLT PET/CT, using different PET/CT semi-quantitative values and a clinical index. We used the International Harmonization Project criteria to assess patient response at the end of treatment, as these criteria are now widely used for response assessment in clinical practice.

In the ROC analysis, the AUC for ΔSUVFDG and ΔSUVFLT were similar, indicating that FLT had a similar diagnostic accuracy to FDG (which is widely applied in clinical trials) in the therapeutic assessment of DLBCL. In this study, we calculated the optimal cut-off value for ΔSUVFDG as 79%, which is higher than reported in some previous studies,12, 13 although it is in line with other studies5, 14 that demonstrated an optimum ΔSUVFDG value higher than 66% (77–81%). This value of 79% resulted in lower sensitivity and higher specificity than the common 66% criterion. However, for FDG, the 66% cut-off still had a higher accuracy than the 79% cut-off, and has been more widely accepted in clinical trials. The reason for the difference may be a statistical issue caused by the relatively small sample size. Studies investigating the maximum and mean SUV of FLT at the initial PET0 stage indicated that FLT correlated with cell expression of Ki67, and was a negative predictor of treatment response in aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, correlating with the IPI score.15, 16 A number of studies have described optimal ΔSUVFLT cut-offs for interim PET/CT based on the researchers’ own experience, with the values ranging from 65 to 74%.17, 18 We therefore chose a value of 66% as a contrast control index (which was equivalent to the value for FDG), and an ROC derived value of 76% for the statistical analysis. Moreover, we must be aware of the difficulties in interpreting these semi-quantitative parameters and keep in mind the fact that it was difficult to make comparisons across the values of different investigations, because of different factors such as the patient population, interpretation of FDG and FLT PET/CT, patient treatment regimens, and statistical methods.

Our study results demonstrated that interim FLT PET/CT had a higher PPV and accuracy, and similar NPV, to the standardized interpretation criteria for FDG PET/CT based on semi-quantitative analysis. For the interim PET/CT assessment, especially after 1–2 cycles of R-CHOP, FLT was more accurate than FDG for predicting patient outcome. Patients with a negative FLT interim PET were likely to be cured with standard chemotherapy. Some investigations have shown that end FDG PET/CT studies were more informative than interim ones, as they were associated with a lower percentage of false-positive findings. This was because a substantial number of positive lesions at interim FDG PET/CT became negative by the end point. Potential explanations for these false-positive interim results include lesion inflammation induced by immunotherapy and rituximab activity, which results in antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and complement system activation. These processes can attract mediators of inflammation to the tumor site, thus causing FDG positivity at interim PET/CT. Some studies have also reported that fewer than half of patients with a positive interim PET/CT relapse after a standard course of immunochemotherapy.19, 20 In our study, not many of the patients who presented with positive signs at the PET2 underwent re-biopsy of suspicious lesions; this was because the physicians in the clinic had confidence in the well-accepted PET/CT and clinical evaluation procedure. We obtained the lowest false positive rate of 14.3% under the criterion of ΔSUVFLT > 76%, which compares with the false positive rate of 50% under ΔSUVFDG > 66%. This indicates, to some extent, that FLT was more specific than FDG, and is in line with the previous reports mentioned above. It is therefore reasonable to use interim FLT PET/CT and end FDG PET/CT to assess the treatment response of DLBCL patients.

The survival curves for PFS and OS demonstrated that both interim FLT and FDG PET/CT resulted in meaningful outcome predictions, indicating that PET/CT is a robust imaging modality for the prognosis of patient survival. Use of the 66% ΔSUVFDG and 76% ΔSUVFLT criteria to predict outcome resulted in the largest significant differences between high and low ΔSUV groups, with ΔSUVFLT in combination with the well-established IPI score representing the best prognostic indicator for PFS and OS. These results demonstrate that FLT PET/CT for in vivo proliferation imaging could be superior to an FDG scan at the interim evaluation, and comparable to the widely accepted clinical standard. However, compared with these two semi-quantitative parameters, the Deauville scale had a relatively high PPV, NPV, and accuracy in the diagnostic test, and a similar p value in the survival analysis. The present study showed similar results to a previous report,21 in that a score of ≥4 was the most reproducible cut-off for the Deauville 5-point scale. Although a previous study has reported that a semi-quantitative SUV-based interim FDG PET study may be more accurate than visual interpretation,22 we still have confidence that visual interpretation for conventional FDG scans is reliable and convenient for clinical use.Deauville scale

With consideration of the high specificity of the 76% ΔSUVFLT criterion and the good sensitivity of Deauville scale, it was possible to construct a new prognostic model combining both visual and semi-quantitative parameters to identify three groups of patients: the first group of patients with a DS 4–5 and ΔSUVFLT ≤ 76% had a poor prognosis, the second group with DS 1–3 and ΔSUVFLT > 76% had a good prognosis, and the third group with one of the two parameters positive and the other negative had an indeterminate prognosis. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of this model were 96.7, 57.1, 82.9, 88.9, and 84.1% respectively, which provides the highest accuracy of any of the examined criteria. This combined prognostic model also means that the patients in Group 1 had a much worse prognosis than the patients in Group 2, with a 3-year PFS of 0% and OS of 33.3% for Group 1, and 89.0 and 92.9% for Group 2. This compares favorably with either the 76% ΔSUVFLT or DS alone. This type of model should be useful in the clinic, to identify the patient group with a prognosis sufficiently poor (the first group above) such that clinicians might consider changing treatment. A similar investigation was reported previously, and it could be applied widely in both clinical practice and future clinical trials.23 However, the ideal prognostic model for lymphoma should combine parameters from pathology, imaging, and clinical evaluations, such as the expression of immunohistochemical markers, PET results, and IPI. It would be an error for clinical doctors to focus on PET analysis alone, and there is little evidence that altering DLBCL treatment on the basis of interim PET changes outcomes.24

We should bear in mind that experience with FLT PET/CT in lymphoma is limited. FLT currently remains an experimental PET tracer and is not widely available at every center or institution. It has a low signal-to-noise ratio and high bone marrow background activity, so often shows as a less intense accumulation in lesions. This leads to difficulties in establishing the interpretation criteria for FLT PET/CT. However, despite these challenges, FLT PET/CT appears to have potential for early monitoring of therapy, and to be useful for guiding treatment strategy. It could be an important factor in adverse prognoses, and could help to define high-risk populations and predict treatment failure in a refractory/relapsed patient cohort, forming an alternative to FDG PET/CT.25, 26

Our study is limited by the small sample size. We initially included over 60 patients; however, because of financial reasons and dosimetry concerns, some of the patients refused to perform one of the two interim PET/CT scans, despite completing both at baseline. Further studies need to be conducted to establish optimal thresholds, optimize evaluation timing and patient selection, analyze parameters other than ΔSUV, and investigate new tracers.

Conclusions

Our present study demonstrated that both interim FDG and FLT PET/CT were important predictors for therapeutic response assessment in DLBCL. FLT had higher specificity and accuracy than standardized FDG PET/CT-based interpretation. Visual analysis was shown to be valid and feasible for assessing the prognostic value of interim FDG PET/CT in daily clinical work. Future work should explore a lymphoma prognostic model combining more parameters.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81450023), Capital Clinical Special Application (Z121107001012116), and a China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (2014M552583).

Acknowledgements: We thank Karl Embleton, PhD, for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ruimin Wang, Email: wrm@yeah.net.

Baixuan Xu, Email: xbx301@163.com.

Changbin Liu, Email: liuchangbin301@126.com.

Zhiwei Guan, Email: 13718806573@139.com.

Jinming Zhang, Email: zhangjm301@163.com.

Fei Li, Email: fayelee1980@sina.com.

Lu Sun, Email: sunlu2008@163.com.

Haiyan Zhu, Email: zhy301@yeah.net.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cultrera JL, Dalia SM. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: current strategies and future directions. Cancer Control 2012; 19: 204–13. doi: 10.1177/107327481201900305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4184–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miyazaki Y, Nawa Y, Miyagawa M, Kohashi S, Nakase K, Yasukawa M, et al. Maximum standard uptake value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is a prognostic factor for progression-free survival of newly diagnosed patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2013; 92: 239–44. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1602-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akkas BE, Vural GU. Standardized uptake value for (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose is correlated with a high International Prognostic Index and the presence of extranodal involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol 2014; 33: 148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Itti E, Meignan M, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Biggi A, Cashen AF, Véra P, et al. An international confirmatory study of the prognostic value of early PET/CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: comparison between Deauville criteria and ΔSUVmax. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013; 40: 1312–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2435-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shipp MA, Harrington DP, Anderson JR. The international non-hodgkin's lymphoma prognostic factors project: a predictive model for aggressive non-hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meignan M, Gallamini A, Meignan M, Gallamini A, Haioun C. Report on the first international workshop on interim-PET scan in lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2009; 50: 1257–60. doi: 10.1080/10428190903040048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3059–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Römer W, Hanauske AR, Ziegler S, Thödtmann R, Weber W, Fuchs C, et al. Positron emission tomography in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: assessment of chemotherapy with fluorodeoxyglucose. Blood 1998; 91: 4464–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buck AK, Halter G, Schirrmeister H, Kotzerke J, Wurziger I, Glatting G, et al. Imaging proliferation in lung tumors with PET: 18F-FLT versus 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med 2003; 44: 1426–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graf N, Herrmann K, Numberger B, Zwisler D, Aichler M, Feuchtinger A, et al. 18F]FLT is superior to [18F]FDG for predicting early response to antiproliferative treatment in high-grade lymphoma in a dose-dependent manner. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013; 40: 34–43. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Casasnovas RO, Meignan M, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Bardet S, Julian A, Thieblemont C, et al. SUVmax reduction improves early prognosis value of interim positron emission tomography scans in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2011; 118: 37–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin C, Itti E, Haioun C, Petegnief Y, Luciani A, Dupuis J, et al. Early 18F-FDG PET for prediction of prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: SUV-based assessment versus visual analysis. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 1626–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Fan Y, Yang Z, Ying Z, Song Y, Zhu J, et al. The prognosis value of early and interim ¹⁸F-FDG-PET/CT scans in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2015; 36: 824–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herrmann K, Buck AK, Schuster T, Rudelius M, Wester HJ, Graf N, et al. A pilot study to evaluate 3'-deoxy-3'-18F-fluorothymidine pet for initial and early response imaging in mantle cell lymphoma. J Nucl Med 2011; 52: 1898–902. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herrmann K, Buck AK, Schuster T, Junger A, Wieder HA, Graf N, et al. Predictive value of initial 18F-FLT uptake in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma receiving R-CHOP treatment. J Nucl Med 2011; 52: 690–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee H, Kim SK, Kim YI, Kim TS, Kang SH, Park WS, et al. Early determination of prognosis by interim 3'-deoxy-3'-18F-fluorothymidine PET in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Nucl Med 2014; 55: 216–22. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.124172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herrmann K, Buck AK, Schuster T, Abbrederis K, Blümel C, Santi I, et al. Week one FLT-PET response predicts complete remission to R-CHOP and survival in DLBCL. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 4050–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cashen AF, Dehdashti F, Luo J, Homb A, Siegel BA, Bartlett NL. 18F-FDG PET/CT for early response assessment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: poor predictive value of international harmonization project interpretation. J Nucl Med 2011; 52: 386–92. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pregno P, Chiappella A, Bellò M, Botto B, Ferrero S, Franceschetti S, et al. Interim 18-FDG-PET/CT failed to predict the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated at the diagnosis with rituximab-CHOP. Blood 2012; 119: 2066–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meignan M, Gallamini A, Itti E, Barrington S, Haioun C, Polliack A. Report on the third international workshop on interim positron emission tomography in lymphoma held in Menton, France, 26-27 September 2011 and menton 2011 consensus. Leuk Lymphoma 2012; 53: 1876–81. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.677535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weber WA. 18F-FDG PET in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: qualitative or quantitative? J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 1580–2. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mikhaeel NG, Smith D, Dunn JT, Phillips M, Møller H, Fields PA, et al. Combination of baseline metabolic tumour volume and early response on PET/CT improves progression-free survival prediction in DLBCL. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 1209–19. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dührsen U, Müller S, Hertenstein B, Thomssen H, Kotzerke J, Mesters R, et al. Positron emission tomography-guided therapy of aggressive non-hodgkin lymphomas (PETAL): a multicenter, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 2024: JCO2017768093–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moskowitz CH, Schöder H, Teruya-Feldstein J, Sima C, Iasonos A, Portlock CS, et al. Risk-adapted dose-dense immunochemotherapy determined by interim FDG-PET in Advanced-stage diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1896–903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carr R, Fanti S, Paez D, Cerci J, Györke T, Redondo F, et al. Prospective international cohort study demonstrates inability of interim PET to predict treatment failure in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Nucl Med 2014; 55: 1936–44. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.145326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]