Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the global leading cause of death. One route to address this problem is using biomedical imaging to measure the molecules and structures that surround cardiac cells. This cellular microenvironment, known as the cardiac extracellular matrix, changes in composition and organization during most cardiac diseases and in response to many cardiac treatments. Measuring these changes with biomedical imaging can aid in understanding, diagnosing, and treating heart disease. This chapter supports those efforts by reviewing representative methods for imaging the cardiac extracellular matrix. It first describes the major biological targets of ECM imaging, including the primary imaging target of fibrillar collagen. Then it discusses the imaging methods, describing their current capabilities and limitations. It categorizes the imaging methods into two main categories: organ-scale noninvasive methods and cellular-scale invasive methods. Noninvasive methods can be used on patients, but only a few are clinically available, and others require further development to be used in the clinic. Invasive methods are the most established and can measure a variety of properties, but they cannot be used on live patients. Finally, the chapter concludes with a perspective on future directions and applications of biomedical imaging technologies.

Keywords: Cardiac, Extracellular matrix, Collagen, Imaging, Composition, Fibers

2.1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death across the globe, and efforts to address this public health problem are increasingly focused on the cardiac extra-cellular matrix (ECM) [75]. The cardiac ECM is a dynamic environment that varies in organization and composition throughout the course of cardiac disease and during normal cardiac development. Knowledge of these changes can help researchers and clinicians understand, detect, and treat cardiac disease [20, 62]. Biomedical imaging is one of the main tools for measuring the cardiac extracellular matrix (ECM), encompassing a range of research and clinical imaging methods that are capable of visualizing different ECM properties and components. However, prospective researchers of the ECM should be aware that there are significant capability gaps in ECM imaging.

ECM imaging is a still-developing field currently defined by the divide between invasive and noninvasive imaging methods [25, 74]. Invasive imaging methods are dominated by microscopy-based applications and are the gold standard for measuring the ECM, but they are limited in their clinical application. They require either cardiac biopsies, which can be damaging to patient health, or are restricted to imaging small areas during surgical interventions or through endoscopes. They are used extensively in engineered tissue and animal models of cardiac disease. In return, they obtain detailed information on the ECM, visualizing fiber networks, proteins, and other ECM components at the cellular and subcellular scales (< 2 μm). By contrast, noninvasive imaging methods can safely be applied to patients but can only provide limited information about the ECM. Noninvasive methods currently image at the organ scale (> 0.5 mm), measuring a small range of bulk ECM properties such as the concentrations of some ECM components, extracellular volume, or tissue mechanical properties. This divide means that invasive imaging methods are used for either ex vivo imaging or preclinical imaging of research models or human tissues, whereas noninvasive methods are suitable for in vivo clinical imaging.

This chapter covers the targets, methods, and applications of imaging the ECM. It begins by discussing the biological targets for ECM imaging, explaining that collagen is one of the primary components targeted by ECM images and why this is so. The chapter then reviews the methods themselves, classifying them into two categories based on common usages and limitations. These categories are noninvasive organ-scale imaging, which is predominant for imaging patients, and invasive cellular-scale imaging, which is largely restricted to ex vivo tissue imaging or in vivo research model imaging but gives the most information about the ECM. Finally, it discusses the future directions of ECM imaging in terms of current research focuses and unmet needs.

2.2. Collagen, Fibrosis, and Other Biological Targets for ECM Imaging

The families of proteins known as fibrillar collagen are the main targets for ECM imaging, with a focus on imaging collagen types I and III. Collagens I and III are the most common ECM components, and they respectively account for 85–90% and 5–11% of collagens in the cardiac ECM [20]. These collagens compose a fibrillar network in cardiac tissue and provide both structural stability and take part in cellular signaling. They are an important imaging target because most cardiac diseases cause increased deposition or rearrangement of collagen in the ECM. These changes are part of the tissue repair and the compensatory mechanism known as fibrosis (Fig. 2.1) [10, 25]. Fibrosis is a process where the ECM thickens, increasing the concentration and arrangement of ECM components. This process increases collagen concentration the most of any component, and changes the organization of collagen networks in ways that can be seen both qualitatively and quantitatively [56]. Fibrosis occurs either in a single focal site of injury or diffusely throughout the diseased tissue, with certain patterns corresponding to particular diseases. Thus, the imaging of collagen can reveal fibrosis, and in doing so screen for or monitor most cardiac diseases [25]. Consequently, the majority of noninvasive imaging methods aim to find areas of fibrosis or to measure collagen concentration, with relatively few examining other ECM components. Invasive imaging is less focused on collagen than noninvasive imaging, but there is also a large body of work with invasive imaging devoted to analyzing collagen networks and structure.

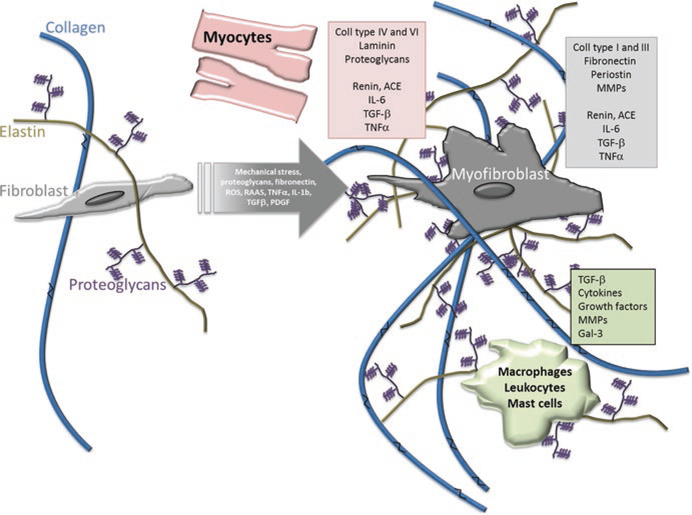

Fig. 2.1.

Stress or damage to the heart triggers myocardial fibrosis, where cells synthesize increased amounts of extracellular matrix components. The largest increase in synthesis is for collagen. (This work is attributed to Gyöngyösi et al. and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license [24])

Most imaging methods are sensitive to fibrillar collagen types I and III, but only a few measure other collagens in the heart [42, 73, 74]. Collagen types I and III form into chains of molecules known as fibrils, which are arranged into a fibrous scaffold. Methods that image types I and III are sensitive to their molecular properties or to the discrete and recognizable fiber network they form [56]. Other collagens are harder to target because they are less prevalent, are non-fibrillar, or are difficult to isolate from other ECM components due to their location. Collagen type IV is part of the basement membrane in the ECM, is intermixed with other proteins, and due to its non-fibrillar makeup lacks the structural imaging contrast of fibrillar collagens. Collagen type V occupies the core of some type I fibers, making them difficult to detect. Finally, type VI collagen forms fibrous structures surrounding individual myocardial cells, arteries, and capillaries (Fig. 2.2) [38, 42, 73]. For cardiac collagen imaging, the collagen properties of interest include the absolute abundance of collagen, the relative abundance of collagen types, the structure/location of the fiber network, and the connection to other constituents of the ECM [23, 49, 52, 56, 73].

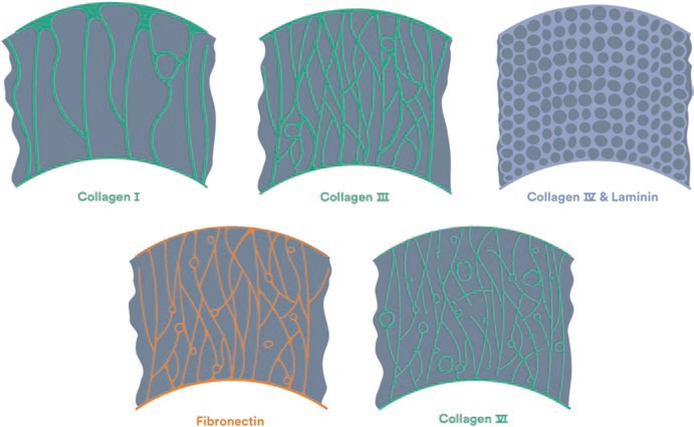

Fig. 2.2.

The fibrous structures in the cardiac extracellular matrix vary in appearance and location. Collagens type I and III are major structural components, which span from major tissue septa such as the epicardium and endocardium. Fibronectin and collagen type VI span from minor septa to the connective tissue of the capillaries and myocardial cells. Finally, laminin and collagen type IV compose the basement membrane [5]. (Figure Permission granted through RightsLink)

Collagen is the most common target for ECM imaging, but less frequent targets include elastin, fibronectin, various receptors, myofibroblasts, as well as other proteins and protein compounds. These targets are less frequently targeted because their sparse concentration and their location in the ECM makes them difficult to distinguish from other targets in non-specific forms of imaging. These targets are typically imaged using high-specificity molecular imaging methods on both the organ and cellular scales. Elastin is a fibrillar protein which complements collagen in structuring the ECM. Collagen contributes to tissue strength, but elastin contributes to tissue flexibility and elasticity, which is important for the constriction and relaxation of the beating heart [71]. Fibronectin is also a fibrillar protein, but its primary role is to convey information between cells and other components of the ECM. It connects between cellular surfaces and to other components, coordinating the development and growth of new cells, and affecting how the cells deposit more components into the ECM [77]. This cellular signaling also involves protein molecules known as receptors, which mediate the cellular response to chemical signals. These receptors can be targeted using protein-specific imaging probes or stains [25]. Myofibroblasts are cells in the ECM that deposit ECM components and can also be a sign of fibrosis. Beyond these targets, specific probes can also target some of the milieu of proteins, and other protein compounds dispersed through the ECM [25].

2.3. ECM Imaging Methods

This chapter divides ECM imaging methods into two categories based on the scale at which they are typically used: organ-scale imaging and cellular-scale imaging (Table 2.1). Organ-scale imaging methods measure bulk properties across large regions of the heart, e.g., the left ventricle. These methods can be used for noninvasive patient imaging, with applications including detection of myocardial fibrosis and monitoring scar tissue formation after myocardial infarction [52, 58]. Cellular-scale imaging methods visualize the ECM components directly at high-resolutions. These methods are invasive, requiring either a biopsy or an imaging probe near the cardiac tissue. Consequently, these methods are currently used to image patient tissue samples or for preclinical research. For example, they have been used to characterize how diseases alter collagen networks in the myocardium and vasculature [23, 28, 46, 71]. Each of these two categories contains several imaging methods, which range in sensitivity (signal strength), specificity (signal source), and cost. These methods are further described in the sections below.

Table 2.1.

Commonly used methods for imaging the ECM in cardiac models

| Imaging spatial scale | Imaging category | Biological source of contrast | Invasiveness | Other limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Organ scale (>100 μm resolution) Organ scale (>100 μm resolution) |

Magnetic resonance imaging | ECM volume, focal fibrosis, diffuse fibrosis, collagen, tropoelastin | Noninvasive, use of contrast agents | Expensive, variable specificity/ sensitivity by technique |

| Ultrasound | Collagen, diffuse fibrosis | Noninvasive | Low specificity for collagen | |

| Nuclear imaging | Collagen, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), integrins, angiotensin receptor, blood coagulation factor FXIII | Noninvasive, requires extrinsic probes | Low resolution, limited probe availability for ECM | |

Cellular scale (< 100 μm resolution) Cellular scale (< 100 μm resolution) |

Tissue staining | Collagen, elastin, fibronectin, various proteins | Invasive, requires biopsy | Tissue processing artifacts, 2D |

| Nonlinear optical microscopy | Fibrillar collagen, elastin, various proteins through probes, chemical environment | Semi-invasive, ~100–300 μm penetration depth or requires biopsy | Low availability, expensive | |

| Electron microscopy | Highest-resolution subcellular and molecular structures | Invasive, requires biopsy, destructive to imaged tissue | Low specificity, low availability, expensive, 2D |

2.4. Organ-Scale Imaging

Organ-scale imaging methods are noninvasive and capable of being used on live patients, making them ideal for clinical imaging. There are strong research efforts going into developing these methods, finding new ways to measure ECM components with molecular imaging, or in better quantifying fibrosis with all approaches. However, these methods cannot directly visualize the ECM because they measure bulk (> 0.5 mm area) properties across large regions of cardiac tissue, such as a ventricle or heart wall. These properties include the volume of the extracellular matrix, the amount or bulk distribution of collagen and other ECM components, and the tissue mechanical properties (an indirect measurement of collagen/elastin structure).

2.4.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The main clinical method for organ-scale collagen imaging is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [52]. MRI, also known as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), is a noninvasive imaging method that perturbs atomic protons/neutrons (typically hydrogen protons) with radiofrequency energy and measures the behavior of those perturbed atoms. The behavior depends on the molecular composition of the tissue and the sequence of radiofrequency pulses used. The sensitivity of the MRI measurements to different molecules (e.g., collagen) varies based on the sequence used and any potential contrast agent. Thus, MRI can be performed through different techniques with varying sensitivity and specificity to collagen or collagen-related properties (e.g., extracellular matrix volume).

There are several techniques used in clinical cardiac MRI. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) MRI is considered the gold standard for identifying scar tissue regions for myocardial fibrosis [60]. However, LGE depends on contrast between the heart regions and so cannot detect diffuse increases in collagen content (Fig. 2.3). Such diffuse increases are associated with early stages of fibrosis. Early stage fibrosis can be detected using the developing class of MRI techniques known as T1 mapping [68]. These T1 mapping MRI sequences provide semiquantitative measures voxel-by-voxel. These maps are useful in clinical diagnosis but have biological and practical limitations. Measured values can be different for normal and diseased tissue, and changes in these values are also associated with other ECM altering diseases (e.g., edema). T1 mapping sequences are not standardized, making measurements difficult to reproduce or interpret across institutions [52]. A final set of techniques, tagging and feature tracking MRI, are reproducible and quantitative, but only indirectly measure collagen or other ECM biology [55]. Tagging and feature tracking measure the mechanical deformation (strain) of the myocardium, which is affected by the collagen structure [52]. These techniques are valuable clinical tools but are not wholly specific to collagen or the ECM.

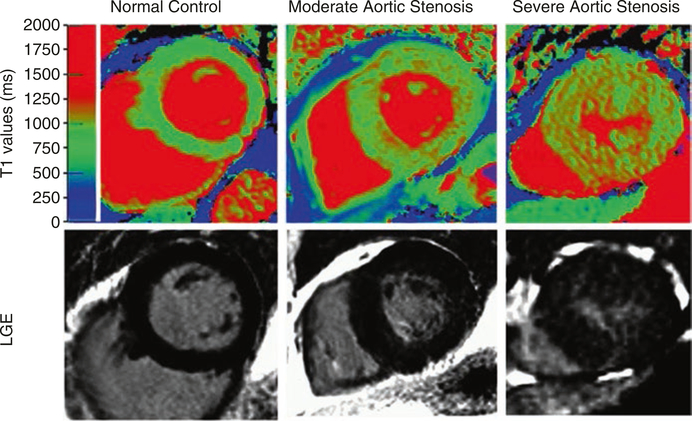

Fig. 2.3.

T1 mapping and late gadolinium enhancement MRI depict regions of high collagen content and fibrosis. This can be seen in aortic valve images from patients. This figure shows three cases in order of increasing fibrosis: a normal control, moderate aortic stenosis, and severe aortic stenosis. (This work is attributed to Bull et al. and used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license [7])

Molecular MRI imaging is a preclinical MRI technique that has very high specificity to collagen and other ECM components. Molecular MRI uses probes that bind to target molecules and which include an MRI contrast agent. These probes are still in the preclinical stage and need further safety and efficacy studies before being brought to the clinic, but they have already shown promise for ECM imaging [52]. Collagen targeted molecular MRI more accurately visualizes scar tissue than other methods of MRI [25]. Molecular MRI targeted at other molecules can study the underlying processes behind fibrosis (apoptosis, necrosis, inflammation, and scar maturation) [52]. Additionally, molecular MRI using an elastin−/tropoelastin-specific agent allowed for the in vivo assessment of ECM remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial infarction [53]. There are no probes for many existing ECM components; however, any molecule can potentially be targeted given the development of an appropriate probe. Such a probe would be both specific to the molecule in question and would include an MRI contrast agent. Molecular MRI has high potential for future clinical work as a noninvasive way of measuring various ECM components in bulk. However, its use will depend on the continued development of imaging probes and their validation through clinical trials.

Overall, MRI is considered a standard tool for assessing fibrosis in the clinic at the organ scale. However, the major limitation of MRI is high expense. This difficulty compounds the issue of imaging standards, where the field of MRI is still developing standards for data acquisition and analysis [52]. The lack of these standards means that MRI data can vary from location to location, which can impact the results. Other limitations include that there are few clinical trials using ECM MRI techniques and that molecular MRI is preclinical and has only a small collection of probes. As such, other imaging methods complement it in the clinic and for research.

2.4.2. Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US), also known as echocardiography, is a widely used clinical imaging modality that is noninvasive, inexpensive, and can assess mechanical properties related to the tissue collagen structure [13]. For example, strain and elastography US assess myocardial deformation and elasticity, both of which are heavily affected by collagen and elastin structure [59]. Integrated backscatter US can detect changes in cardiac collagen density, which is a major feature of fibrosis [21]. In addition, US is sensitive to the angle and amount of collagen fiber alignment in a region [32, 54, 57]. However, these techniques have low collagen specificity because they are also affected by other biological structures, e.g., muscle fibers. In addition, these techniques currently have low reproducibility between different US labs and require high image quality, leading to variable results between labs [74]. As such, while US is a valuable clinical modality that is widely used for qualitative cardiac imaging, it is not currently used for quantitative cardiac ECM imaging. This may change in the future, as researchers improve current methods or develop more reproducible methods of differentiating regions in US images. One example of this are alternative metrics that rely on tissue texture, paired with computer models to automate image assessment [66].

2.4.3. Nuclear Imaging

Nuclear imaging methods have the highest specificity and sensitivity but are limited by low resolution and the need to develop clinically compatible imaging probes [25]. Cardiac nuclear imaging uses two methods, known as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron-emission tomography (PET). Nuclear imaging uses radioactive probes that bind to target molecules. Currently, there are no clinical probes that target collagen, but there are several at the preclinical stage that have been tested on animal models for fibrosis. In cardiac models, SPECT and PET probes based on a peptide known as collagelin accumulate in areas of myocardial infarction (Fig. 2.4) [33, 47]. In lung and liver models, other peptide-based probes accumulate in fibrotic tissue ([14, 78], p. 201). There have been few other probes demonstrated in the literature, but a recent review has highlighted potential targets for collagen probes [72]. These targets include intact collagens I, II, and IV but also include degraded collagens I–V, which are found in fibrotic tissue and other sites of collagen remodeling. Beyond collagen, there are also many probes that target components of the ECM, including matrix metalloproteinases, integrins, a blood coagulation factor, and angiotensin receptors [76]. As such, nuclear imaging of the cardiac ECM is a promising imaging method for preclinical imaging. Ultimately, the clinical use of nuclear imaging depends on further developing these probes to be reproducible and to demonstrate their safety through clinical trials.

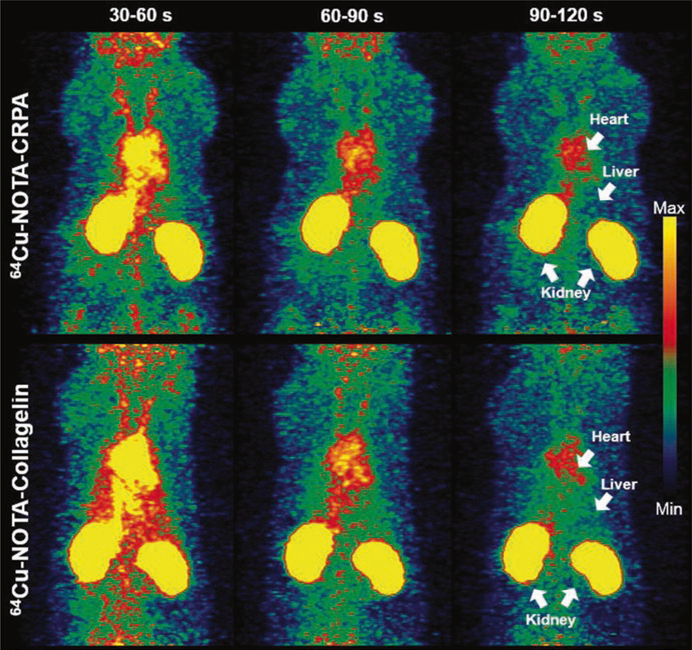

Fig. 2.4.

Collagelin and collagelin analogue probes accumulate in regions of myocardial infarction and fibrosis in rat models. This figure depicts positron-emission tomography images taken at several time points after probe injection. The top row shows a probe based on the collagelin analogue CRPA, and the bottom a probe based on collagelin [33]. (Figure Permission granted through RightsLink)

2.5. Cellular–Scale Imaging

Imaging methods at the cellular scale visualize the organization of the ECM but are invasive and cannot currently be used on live patients. For fibrous components, this organization includes properties such as fiber density, diameter, alignment, cross-linking between fibers, and more. These methods either require patient biopsies or use surgical and endoscopic tools to image the tissue in the clinic. Some of these methods can be used in vivo in cardiac research models such as the fish [70]. There are three major categories of methods for imaging collagen on the cellular size scale: tissue staining protocols, nonlinear optical microscopy, and electron microscopy.

2.5.1. Tissue Staining Protocols

Tissue staining protocols (histochemistry and immunohistochemistry) are the most clinically accessible means of visualizing collagen in the ECM. Staining protocols take thin (1–10 μm) tissue sections and label components of the ECM and cellular microenvironments. Histochemistry uses chemical dyes that bind to various tissue components, coloring them in the process. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) relies on antibodies that bind to protein antigens in the tissue. These antibodies localize to the areas containing the protein of interest and are labeled with a reporter molecule (e.g., a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody) for imaging. For both methods, the resulting slides can be analyzed using a standard wide field optical microscope, equipped with fluorescence in the case of IHC.

The primary advantages of staining methods are the ability to target many different components and ease-of-use, but there are many limitations on application. There is a large library of stains for comparing different biological components, giving staining methods applicability for many research problems. IHC in particular can be protein specific, allowing stains to target many of the proteins of the ECM. Staining methods have a widespread availability because optical microscopy is relatively inexpensive and already available in most clinical and research environments. Finally, these methods are the oldest and best established, meaning they are considered the gold standard and are prevalent in the literature. However, tissue staining protocols are also subject to several limitations. They require biopsies of cardiac tissue and so cannot image the environment of live cells. These biopsies can be difficult to acquire without hurting the patient and are often unavailable [10]. The biopsies may not be representative of the diseased tissue, as they cover only a small portion of the tissue, and thus are subject to sampling errors. In addition, staining protocols involve processing steps which often deform or alter the tissue from the original tissue structure [1, 12]. Finally, the tissue sections are typically imaged in 2D and so provide a limited view of collagen organization across the whole tissue, preventing robust 3D quantitative analysis. Researchers are addressing the 3D issue by developing rapid imaging and image fusion for series of adjacent slides, but the difficulties of using such image fusion schemes mean that other 3D imaging methods may remain more attractive options [3]. For these reasons, tissue staining protocols have a limited quantitative value in measuring collagen or other components of the ECM; however, they remain the standard for cardiac care and research because of their qualitative value [10].

Stains are a common method for looking at collagen structure. In the clinic, they can be used to assess fibrosis based on clinician judgment. In addition, researchers are developing quantitative computer-based methods to analyze microscopy slides [64]. Some notable collagen stains include the Picrosirius red, hematoxylin and eosin, trichrome, and antibody stains [11, 36, 45]. The Picrosirius red stain is the highly specific to collagen and can further serve as a contrast agent when combined with polarized light microscopy (PLM). This combination can quantify the collagen fiber orientation and organization in 2D [36]. Other stains, such as hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and trichrome stains, are less specific to collagen and more difficult to quantify but allow collagen to be viewed in the context of the rest of the ECM. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) protocol stains components of the ECM in shades of blue and pink, with collagen a pink shade, yielding shades for each component that reflect how well they bind either dyes [11]. Trichrome stains are a collection of over one hundred stains which dye collagen, muscle, and a third biological component in three different colors [45]. Finally, antibody stains use antibodies to bind collagen molecules, and certain procedures can use them to distinguish between collagen types I and V [39, 48]. These four stains are prevalent for imaging collagen, but it should be noted that there are other collagen stains and stains that can be used to differentiate other elements of the ECM.

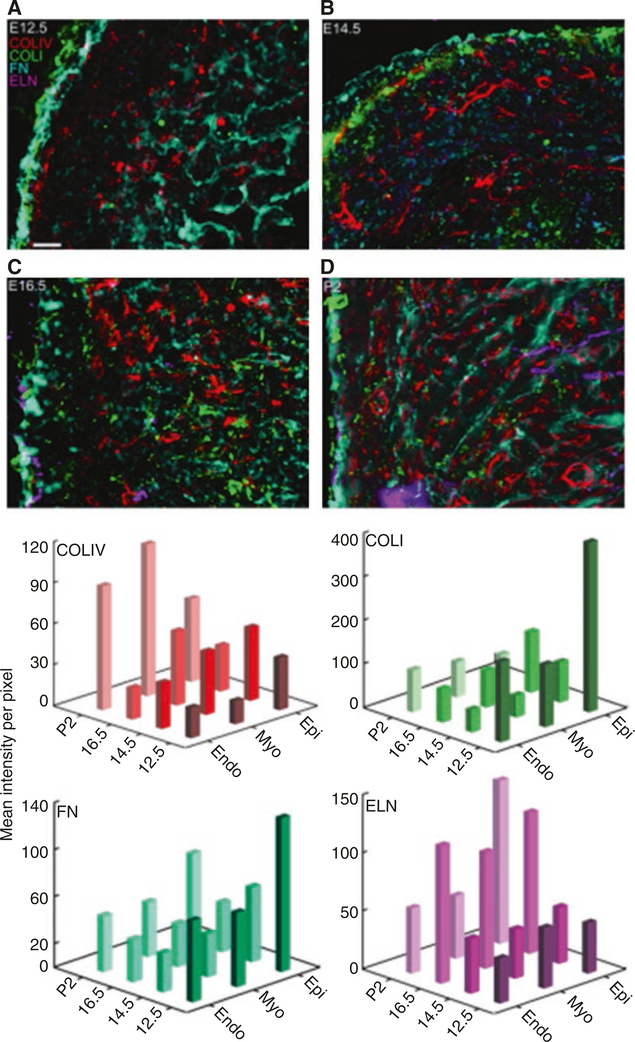

IHC stains are also the primary method for imaging elastin and fibronectin in the heart. Early work has shown fibronectin labeling in endocardial and myocardial tubes of a stage 22 embryonic chick heart [40]. Additional work in embryonic chick hearts over several stages of embryonic development demonstrates the dynamics of elastin expression [27]. More recent studies have revealed how the expression and distribution of fibronectin and elastin vary across the developmental stages of the murine heart [26]. For example, Hanson et al. found that there is fibronectin in the left ventricle’s epicardium and endocardium in embryonic and early postnatal mouse hearts. However, fibronectin fibrils did not form in the myocardium until embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), at which point they continued to increase in density through early postnatal development. Similarly, elastin did not appear in the heart until E16.5, where it began to organize into fibrils in all three regions of the ventricle as well as the blood vessel walls. Fluorescent images from IHC were quantified using mean intensity per pixel values in order to compare relative protein amounts. This, along with the IHC mapping of other ECM proteins found in the heart (Collagen I, Collagen IV) (Fig. 2.5), begin to provide a blueprint for the spatial and temporal organization of proteins critical for cardiac development and function.

Fig. 2.5.

IHC labeled sections of the murine ventricle over the course of development (a–d). Red, Col IV; green, Col I; cyan, fibronectin; magenta, Elastin. (e) Quantitative comparison of ECM proteins across development in each cardiac tissue layer. Endo, endocardium; Myo, myocardium; Epi, epicardium (Hanson, [31]). (Copyright granted as paper coauthor (Eliceiri))

2.5.2. Nonlinear Optical Microscopy

Nonlinear optical microscopy (NLO) methods generate label-free high-resolution images at greater imaging depths and higher signal-to-noise ratio than conventional optical imaging such as laser scanning confocal microscopy [35]. These methods are based on nonlinear interactions between light and biological tissues. NLO methods can be used to perform nondestructive imaging that is capable of quantifying collagen and other ECM components in 3D, does not require tissue-damaging labels, and minimizes phototoxic effects in live tissue. They can typically image through 100–300 μm thick cardiovascular tissue, deriving contrast from intrinsic biology and optionally from extrinsic contrast agents [9, 10]. They are currently used to study biopsies and live animal models, but they can potentially be used on patients through endoscopic or surgical probes [4, 10]. The downside of these methods is low availability, expensive equipment requirements, and the need for experienced technicians. However, there are many efforts to develop cheaper and more clinically friendly NLO equipment such as endoscopes that could make these methods more widespread and available for ECM imaging [41]. In addition, NLO methods share most of the same equipment and so can often be implemented on the same workstation and used alongside each other [10, 56].

Combinations of NLO methods are highly effective in characterizing the ECM, as each method derives contrast from a different source. Thus far, the two primary NLO methods for cardiac imaging are second harmonic generation (SHG) and two-photon excited fluorescent (2PEF), which we review below. Another emerging NLO method, Coherent anti-Stokes Raman (CARS) microscopy [35], has been used for imaging atherosclerosis and heart valve stenosis, but its applications overall for ECM imaging are still being explored [8, 37]. Fluorescent methods can also be combined with NLO for additional contrast such as the NLO compatible method of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to examine the chemical microenvironment of the ECM [35].

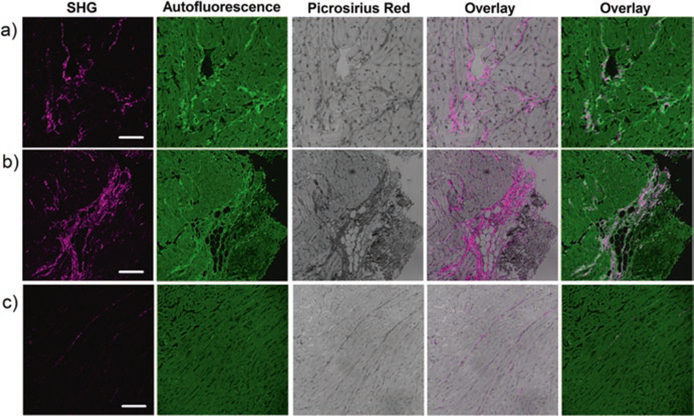

SHG can obtain highly specific images of fibrillar collagen in the ECM without the use of extrinsic probes, allowing it to image collagen in live tissue (Fig. 2.6). SHG derives contrast from non-centrosymmetric molecules such as fibrillar collagen (I/III/V), elastin, and myosin. Both collagen and myosin are present in cardiovascular tissue; however, the SHG signal is highly specific to collagen (>95%) at low laser powers (10–20 mw) (Fig. 2.6) [10]. These qualities allow SHG to quantify collagen fiber organization in many cardiovascular diseases, including fibrosis, cardiomyopathy, scar formation after a heart attack, and aortic stenosis [10, 16, 49, 58, 63]. The main limitation of SHG for clinical studies is limited depth due to scattering and refractive index effects of the tissue that attenuate the collected signal. As well, the polarization state of the laser and the orientation of the fibers to the laser can both affect the signal strength. The former can be mitigated using circularly polarized light, but the latter is an intrinsic limitation and affects the signal from collagen fibers between imaging planes [9].

Fig. 2.6.

Second harmonic generation (SHG) can image cardiac fibrillar collagen at high specificity and high resolution. These panels show SHG, autofluorescence, and Picrosirius red stained imaging of a myocardial infarction rat model (a and b) and an age-matched control (c). The SHG is overlaid onto the Picrosirius red and autofluorescence stains in the fourth and fifth columns, respectively. (This work is attributed to Caorsi et al. and used through the Creative Commons Attribution license [10])

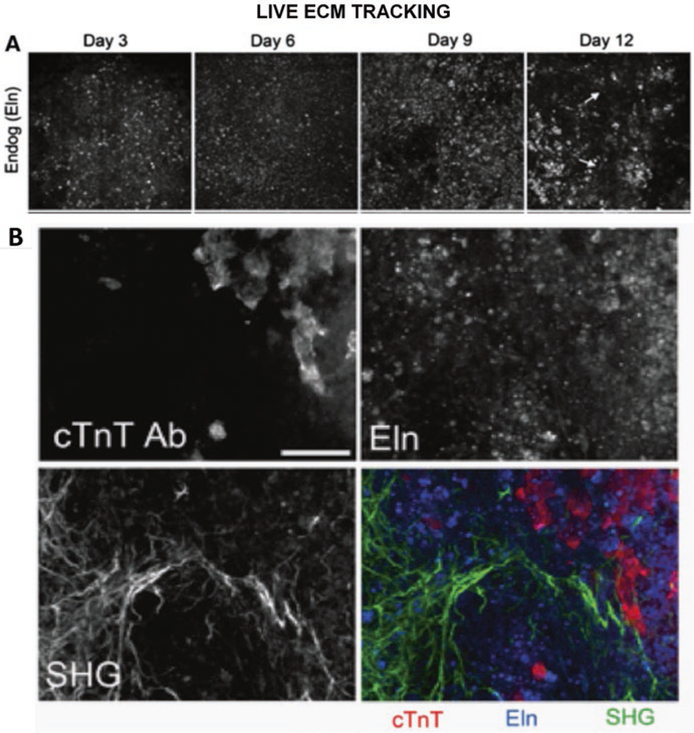

2PEF images fluorescent molecules and so can derive contrast from both intrinsic and biocompatible extrinsic sources, which means that it can be used on live tissue and be enhanced using probes. The intrinsic sources include collagen, elastin, and myocyte proteins [10]. Extrinsic 2PEF is currently less common than intrinsic imaging for cardiac ECM studies, as there are few suitable fluorescent probes. However, researchers are facing this problem and developing new methods and identifying suitable probes [15, 67]. 2PEF is easily implemented on the same system as SHG, and so they are often used in conjunction. This pairing visualizes several components of the ECM in the same imaging volume and allows collagen to be separated from other components. For example, tracking elastin deposition during in vitro mouse embryoid body development reveals that the ECM expression transitions from a punctate to fibril-like structure over time (Fig. panel 2.7a) and is spatially associated with cells exhibiting markers of cardiomyocyte maturity (Fig. panel 2.7b) [69].

Fig. 2.7.

Panel (a) Endogenous elastin fluorescence over time. Panel (b) Spatial relationship between elastin, collagen, and cardiomyocytes in embryoid bodies [69]. (Copyright granted as paper coauthor (Eliceiri))

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is a 2PEF compatible quantitative imaging method that measures the time a fluorophore stays in the excited state and is sensitive to changes in the microenvironment such as pH and protein binding [6]. FLIM is currently less common than SHG or 2PEF but can offer unique capabilities for ECM imaging. The lifetime is related to molecular properties including the pH of its surroundings, the concentration of oxygen near the molecule, and the molecule’s bonds to other molecules [6]. FLIM has been used to image atherosclerotic plaques, helping characterize the plaque composition [30, 51]. FLIM may have uses in cardiac myopathy, where the ratio of collagen I and III fibers matters. A previous study showed that FLIM can be used in combination with SHG to separate intrinsic fluorescence signal from collagens I and III, though it was not demonstrated in cardiac tissue [56].

In summation, these NLO imaging methods offer 3D imaging on the cellular size scale and in live tissue. They are currently used in research applications but can potentially be implemented in clinic given emerging advances in less expensive, more modular NLO implementation and endoscope-based NLO imaging.

2.5.3. Electron Microscopy

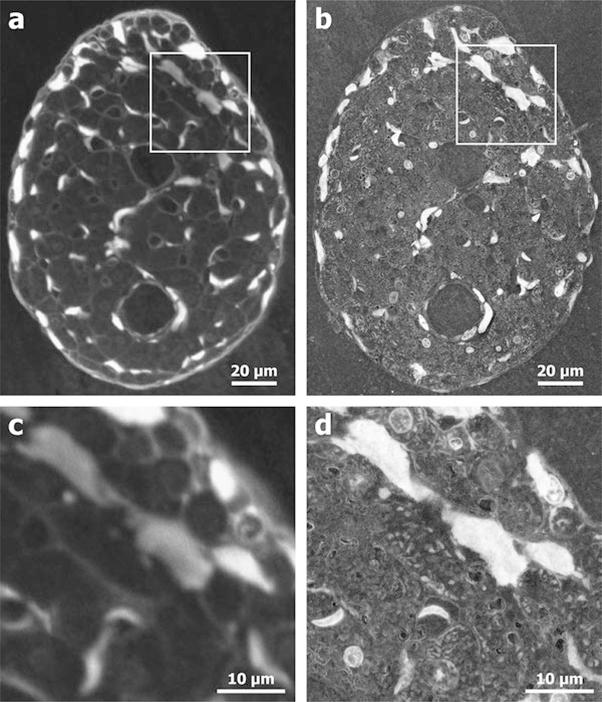

Electron microscopy (EM) is the highest resolution imaging category mentioned in this chapter and is capable of resolving biology smaller than the resolution limits of light microscopy. There are other similarly high-resolution imaging methods with potential for cardiac ECM imaging such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) and super resolution optical imaging [17, 19], but we do not review them due their infrequent use in cardiac ECM imaging. EM is a category of imaging methods that use electrons to create the image, achieving much higher resolution than optical-based methods. Cardiac imaging studies primarily use transmission electron tomography (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). However, there are also powerful EM variants such as environmental S/TEM (E-S/TEM) [34], immuno-EM [43], and Cryo-EM [18] that can image the structure of individual cardiac ECM proteins or offer advantages in contrast and visualization. The high-resolutions EM can visualize the molecular structure of ECM components, e.g., collagen fibrils. Such high-resolution molecular information is valuable for many research applications.

However, EM is subject to several limitations that prevent it from being used clinically. EM is expensive and requires highly specialized training, limiting the number of locations that can perform it. It requires tissue samples, such as from biopsies, which are often unavailable in clinical care. In addition, most forms of EM currently involve extensive sample preparation and process or destroy the tissue samples during imaging, making it impossible to image with other methods [44]. As such, EM can offer valuable research insights about disease biology but is less likely to be used routinely for patient care due to specimen preparation requirements and high cost.

EM has been used in a range of cardiac applications from disease models to basic physiology to cardiac tissue engineering. In models for early stage heart failure, TEM was able to detect fibrotic changes in collagen before other collagen imaging methods [64]. TEM has also been used in the field of cardiac tissue engineering to validate the structure of collagenous scaffolds meant for cardiac tissue patches [65]. Additionally, TEM has been useful in cardiac physiology research. The bulbus arteriosus, an elastic chamber in the heart, appears to be a dense (presumably rigid) collagen matrix under immunohistochemistry, but EM showed an interwoven collagen-elastin matrix, giving a much more accurate view of the physiology [29]. In models of myocardial infarction, SEM analysis of collagen fibril structure showed that osteoglycin promotes proper collagen maturation and improves tissue healing outcomes [2]. In models for calcific aortic stenosis, a disease where minerals are heavily deposited in the ECM, SEM showed how the mineral deposits develop in the interior of collagen fibers [50]. Finally, Sands et al. used E-SEM to visualize the cardiac ventricular trabeculae carneae, strands of axially arranged tissue in the heart. They showed that collagen content and microstructure varied widely, ranging from 1% to 100% of the tissue cross section in different areas (Fig. 2.8) [61].

Fig. 2.8.

Electron microscopy (b, d) can resolve biological structures in the cardiac trabecula that are beyond the resolution limit of confocal microscopy (a, c) [61]. (Figure permission granted through RightsLink)

2.6. Future Directions

Knowledge of the composition and topography of the human heart can improve clinical evaluation as well as help develop treatment strategies; however, acquiring this knowledge in a noninvasive method is a continuing challenge of the field. There is a need for noninvasive imaging methods that are component-specific, high-resolution, and cost-effective for use in the clinic. Researchers are making progress on each of these areas, but there still remains much to be done. The best developed methods for imaging individual components of the ECM are invasive, e.g., histochemistry requiring biopsies. Recent advances in molecular MRI and nuclear imaging show promise for low-resolution organ-scale imaging of ECM components, providing probes for imaging collagen, elastin, receptors, and matrix metalloproteinases [25]. However, the existing probes still require development and validation through clinical trials, and there are no probes for many other ECM components of interest. Other advances may address the difficulty of high-resolution imaging. NLO methods can image ECM components at the cellular-scale without labels and in 3D up to a depth of several hundred microns. However, they are currently expensive, require trained technicians, and most implementations cannot be used on patients. Future advances may change this with the development of endoscopes, simplification of equipment, and corresponding reduced cost. Overall, ECM imaging is heading in promising directions that may help improve clinical outcomes and the role of the ECM in heart physiology.

The previous sections have covered ECM imaging in regard to disease screening, therapy targeting, and diagnostics, but there is also a strong need for such noninvasive ECM imaging in the field of tissue engineering and regeneration. The native composition and organization of ECM proteins can serve as a template for ECM-mimicking tissue engineering strategies. Hydrogels that incorporate ECM molecules such as collagen and laminin support mouse-induced pluripotent stem cell (miPSC) cardiomyocyte differentiation [31], while tissue regeneration structures modeled after the fibronectin distribution in a mouse heart support cardiomyocyte function in a mouse model of myocardial infarction [22]. The field of tissue regeneration can also benefit from knowing the role and organization of specific ECM molecules in cardiac tissue development. Many tissue regeneration strategies are based on mimicking the native ECM composition and architecture. Future advances in cardiac tissue regeneration will rely on the discovery of the critical combinations and organizations of ECM molecules for cardiac function. Thus, both tissue engineering and tissue regeneration would benefit from future developments for advanced ECM imaging methods.

2.7. Conclusion

The field of cardiac ECM imaging is in a rapidly advancing state; it is in the middle of an evolution from primarily invasive imaging with small ex vivo samples to more noninvasive imaging that can measure large regions of the human heart in the clinic. In the past, the only option was for invasive imaging of small samples, but this is beginning to change as researchers approach the problem from two angles. The first is by developing low-resolution, but high-specificity, imaging methods that be used clinically to measure the bulk composition of the ECM. The second is in improving high-resolution methods by reducing costs and developing better form factors, so they can be used with minimal invasiveness in the clinic. The combination of these approaches will improve researcher and clinician ability to nondestructively evaluate the composition of the heart. In the future, these advanced imaging methods will propel both the clinical and research fields toward strategies for enhanced patient care, aiding in the fields of cardiac development, disease, tissue engineering, and tissue regeneration.

Acknowledgment

We thank Brenda Ogle and Ellen Arena for useful input. We also acknowledge funding from the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation, the Morgridge Institute for Research, NIH R01 HL137204 (RAH), NIH R01 131017 (RAH), NIH T32 CA009206 (MAP), and the NIH T32 GM008349 (MAP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

Contributor Information

Michael A. Pinkert, Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation and Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin at Madison, Madison, WI, USA Morgridge Institute for Research, Madison, WI, USA.

Rebecca A. Hortensius, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Brenda M. Ogle, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Kevin W. Eliceiri, Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation and Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin at Madison, Madison, WI, USA Morgridge Institute for Research, Madison, WI, USA, eliceiri@wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Abe M, Takahashi M, Horiuchi K, Nagano A. The changes in crosslink contents in tis-sues after formalin fixation. Anal Biochem. 2003;318:118–23. 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00194-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aelst LNLV, Voss S, Carai P, Leeuwen RV, Vanhoutte D, Wijk SS, Eurlings L, Swinnen M, Verheyen FK, Verbeken E, Nef H, Troidl C, Cook SA, Rocca H-PB-L, Möllmann H, Papageorgiou A-P, Heymans S. Osteoglycin Prevents Cardiac Dilatation and Dysfunction After Myocardial Infarction Through Infarct Collagen StrengtheningNovelty and Significance. Circ Res. 2015;116:425–36. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Janabi S, Huisman A, Van Diest PJ. Digital pathology: current status and future perspectives. Histopathology. 2012;61:1–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao H, Boussioutas A, Jeremy R, Russell S, Gu M. Second harmonic generation imaging via nonlinear endomicroscopy. Opt Express. 2010;18:1255 10.1364/OE.18.001255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashey RI, Martinez-Hernandez A, Jimenez SA. Isolation, characterization, and localization of cardiac collagen type VI Associations with other extracellular matrix components. Circ Res. 1992;70:1006–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker W Fluorescence lifetime imaging – techniques and applications. J Microsc. 2012;247:119–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2012.03618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull S, White SK, Piechnik SK, Flett AS, Ferreira VM, Loudon M, Francis JM, Karamitsos TD, Prendergast BD, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Moon JC, Myerson SG. Human non-contrast T1 values and correlation with histology in diffuse fibrosis. Heart. 2013;99:932–7. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büttner P, Galli R, Jannasch A, Schnabel C, Waldow T, Koch E. Heart valve stenosis in laser spotlights: Insights into a complex disease. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2014;58:65–75. 10.3233/CH-141882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campagnola P Second harmonic generation imaging microscopy: applications to diseases diagnostics. Anal Chem. 2011;83:3224–31. 10.1021/ac1032325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caorsi V, Toepfer C, Sikkel MB, Lyon AR, MacLeod K, Ferenczi MA. Non-Linear Optical Microscopy Sheds Light on Cardiovascular Disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56136 10.1371/journal.pone.0056136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JKC. The Wonderful Colors of the Hematoxylin–Eosin Stain in Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22:12–32. 10.1177/1066896913517939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatterjee S Artefacts in histopathology. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol JOMFP. 2014;18:S111–6. 10.4103/0973-029X.141346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dave JK, Mc Donald ME, Mehrotra P, Kohut AR, Eisenbrey JR, Forsberg F. Recent technological advancements in cardiac ultrasound imaging. Ultrasonics. 2018;84:329–40. 10.1016/j.ultras.2017.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Désogère P, Tapias LF, Rietz TA, Rotile N, Blasi F, Day H, Elliot J, Fuchs BC, Lanuti M, Caravan P. Optimization of a collagen-targeted positron emission tomography probe for molecular imaging of pulmonary fibrosis. J Nucl Med jnumed. 2017;117:193532 10.2967/jnumed.117.193532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drobizhev M, Makarov NS, Tillo SE, Hughes TE, Rebane A. Two-photon absorption properties of fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2011;8:393–9. 10.1038/nmeth.1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Echegaray K, Andreu I, Lazkano A, Villanueva I, Sáenz A, Elizalde MR, Echeverría T, López B, Garro A, González A, Zubillaga E, Solla I, Sanz I, González J, Elósegui-Artola A, Roca-Cusachs P, Díez J, Ravassa S, Querejeta R. Role of Myocardial Collagen in Severe Aortic Stenosis With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Symptoms of Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed. 2017;70:832–40. 10.1016/j.rec.2016.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eghiaian F, Rico F, Colom A, Casuso I, Scheuring S. High-speed atomic force microscopy: Imaging and force spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3631–8. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez-Leiro R, Scheres SH. Unravelling biological macromolecules with cryo-electron microscopy., Unravelling the structures of biological macromolecules by cryo-EM. Nature. 2016;537:339–46. 10.1038/nature19948. 10.1038/nature19948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fornasiero EF, Opazo F. Super-resolution imaging for cell biologists. Bioessays. 2015;37:436–51. 10.1002/bies.201400170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix in myocardial injury, repair, and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1600–12. 10.1172/JCI87491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galetta F, Franzoni F, Bernini G, Poupak F, Carpi A, Cini G, Tocchini L, Antonelli A, Santoro G. Cardiovascular complications in patients with pheochromocytoma: A mini-review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:505–9. 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao L, Kupfer ME, Jung JP, Yang L, Zhang P, Da Sie Y, Tran Q, Ajeti V, Freeman BT, Fast VG, Campagnola PJ, Ogle BM, Zhang J. Myocardial Tissue Engineering With Cells Derived From Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and a Native-Like, High-Resolution, 3-Dimensionally Printed Scaffold. Circ Res. 2017;120:1318–25. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goergen CJ, Chen HH, Sakadžić S, Srinivasan VJ, Sosnovik DE. Microstructural characterization of myocardial infarction with optical coherence tractography and two-photon microscopy. Physiol Rep. 2016;4:e12894 10.14814/phy2.12894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyöngyösi M, Winkler J, Ramos I, Do Q-T, Firat H, McDonald K, González A, Thum T, Díez J, Jaisser F, Pizard A, Zannad F. Myocardial fibrosis: biomedical research from bench to bedside. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:177–91. 10.1002/ejhf.696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Haas HJ, Arbustini E, Fuster V, Kramer CM, Narula J. Molecular Imaging of the Cardiac Extracellular Matrix. Circ Res. 2014;114:903–15. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson KP, Jung JP, Tran QA, Hsu S-PP, Iida R, Ajeti V, Campagnola PJ, Eliceiri KW, Squirrell JM, Lyons GE, Ogle BM. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Extracellular Matrix Proteins in the Developing Murine Heart: A Blueprint for Regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1132–43. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurle JM, Kitten GT, Sakai LY, Volpin D, Solursh M. Elastic extracellular matrix of the embryonic chick heart: an immunohistological study using laser confocal microscopy. Dev Dyn. 1994;200:321–32. 10.1002/aja.1002000407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutson HN, Marohl T, Anderson M, Eliceiri K, Campagnola P, Masters KS. Calcific Aortic Valve Disease Is Associated with Layer-Specific Alterations in Collagen Architecture. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163858 10.1371/journal.pone.0163858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Icardo JM. Collagen and elastin histochemistry of the teleost bulbus arteriosus: False positives. Acta Histochem. 2013;115:185–9. 10.1016/j.acthis.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jo JA, Park J, Pande P, Shrestha S, Serafino MJ, Jimenez Jde J R, Clubb F, Walton B, Buja LM, Phipps JE, Feldman MD, Adame J, Applegate BE. Simultaneous morphological and biochemical endogenous optical imaging of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:910–8. 10.1093/ehjci/jev018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung JP, Sprangers AJ, Byce JR, Su J, Squirrell JM, Messersmith PB, Eliceiri KW, Ogle BM. ECM-incorporated hydrogels cross-linked via native chemical ligation to engineer stem cell microenvironments. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:3102–11. 10.1021/bm400728e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan Z, Boughner DR, Lacefield JC. Anisotropy of High-Frequency Integrated Backscatter from Aortic Valve Cusps. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1504–12. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim H, Lee S-J, Kim JS, Davies-Venn C, Cho H-J, Won SJ, Dejene E, Yao Z, Kim I, Paik CH, Bluemke DA. Pharmacokinetics and microbiodistribution of 64Cu-labeled collagen binding peptides in chronic myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun. 2016;37:1306–17. 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirk S e, Skepper J n, Donald A m. Application of environmental scanning electron microscopy to determine biological surface structure. J Microsc. 2009;233:205–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2009.03111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krafft C Modern trends in biophotonics for clinical diagnosis and therapy to solve unmet clinical needs. J Biophotonics. 2016;9:1362–75. 10.1002/jbio.201600290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lattouf R, Younes R, Lutomski D, Naaman N, Godeau G, Senni K, Changotade S. Picrosirius Red Staining: A Useful Tool to Appraise Collagen Networks in Normal and Pathological Tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62:751–8. 10.1369/0022155414545787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le TT, Langohr IM, Locker MJ, Sturek M, Cheng J-X. Label-free molecular imaging of atherosclerotic lesions using multimodal nonlinear optical microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:054007 10.1117/1.2795437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leeming DJ, Karsdal MA, 2016. Chap..5 – Type V Collagen In: Biochemistry of Collagens, Laminins and Elastin. Academic Press. p; 43–48. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809847-9.00005-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Ho D, Meng H, Chan TR, An B, Yu H, Brodsky B, Jun AS, Yu SM. Direct detection of collagenous proteins by fluorescently labeled collagen mimetic peptides. Bioconjug Chem. 2013;24:9–16. 10.1021/bc3005842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Little CD, Piquet DM, Davis LA, Walters L, Drake CJ. Distribution of laminin, collagen type IV, collagen type I, and fibronectin in chicken cardiac jelly/basement membrane. Anat Rec. 1989;224:417–25. 10.1002/ar.1092240310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Lim KC, Li H, Seck HL, Yu X, Kok SW, Zhang Y, 2015. Low cost and compact nonlinear (SHG/TPE) laser scanning endoscope for bio-medical application. 93041 K–93041 K–6. 10.1117/12.2078809 [DOI]

- 42.López B, González A, Díez J. Circulating Biomarkers of Collagen Metabolism in Cardiac Diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:1645–54. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayhew TM, Lucocq JM. Developments in cell biology for quantitative immunoelectron microscopy based on thin sections: a review. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:299–313. 10.1007/s00418-008-0451-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald KL. Out with the old and in with the new: rapid specimen preparation procedures for electron microscopy of sectioned biological material. Protoplasma. 2014;251:429–48. 10.1007/s00709-013-0575-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGavin MD. Factors Affecting Visibility of a Target Tissue in Histologic Sections. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:9–27. 10.1177/0300985813506916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mostaço-Guidolin L, Rosin NL, Hackett T-L. Imaging Collagen in Scar Tissue: Developments in Second Harmonic Generation Microscopy for Biomedical Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1772 10.3390/ijms18081772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muzard J, Sarda-Mantel L, Loyau S, Meulemans A, Louedec L, Bantsimba-Malanda C, Hervatin F, Marchal-Somme J, Michel JB, Le Guludec D, Billiald P, Jandrot-Perrus M. Non-Invasive Molecular Imaging of Fibrosis Using a Collagen-Targeted Peptidomimetic of the Platelet Collagen Receptor Glycoprotein VI. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5585 10.1371/journal.pone.0005585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pataridis S, Eckhardt A, Mikulíková K, Sedláková P, Mikšík I. Identification of collagen types in tissues using HPLC-MS/MS. J Sep Sci. 2008;31:3483–8. 10.1002/jssc.200800351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauschinger M, Knopf D, Petschauer S, Doerner A, Poller W, Schwimmbeck PL, Kühl U, Schultheiss H-P. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Is Associated With Significant Changes in Collagen Type I/III ratio. Circulation. 1999;99:2750–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.21.2750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perrotta I, Davoli M. Collagen Mineralization in Human Aortic Valve Stenosis: A Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy Analysis. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2014;38:281–4. 10.3109/01913123.2014.901468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phipps JE, Sun Y, Fishbein MC, Marcu L. A Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Classification Method to Investigate the Collagen to Lipid Ratio in Fibrous Caps of Atherosclerotic Plaque. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:564–71. 10.1002/lsm.22059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Podlesnikar T, Delgado V, Bax JJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging to assess myocardial fibrosis in valvular heart disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017:1–16. 10.1007/s10554-017-1195-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Protti A, Lavin B, Dong X, Lorrio S, Robinson S, Onthank D, Shah AM, Botnar RM. Assessment of Myocardial Remodeling Using an Elastin/Tropoelastin Specific Agent with High Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001851 10.1161/JAHA.115.001851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin X, Fei B. Measuring Myofiber Orientations from High-frequency Ultrasound Images Using Multiscale Decompositions. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59:3907–24. 10.1088/0031-9155/59/14/3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin X, Riegler J, Tiburcy M, Zhao X, Chour T, Ndoye B, Nguyen M, Adams J, Ameen M, Denney TS, Yang PC, Nguyen P, Zimmermann WH, Wu JC. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Cardiac Strain Pattern Following Transplantation of Human Tissue Engineered Heart Muscles. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004731 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.004731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ranjit S, Dvornikov A, Stakic M, Hong S-H, Levi M, Evans RM, Gratton E. Imaging Fibrosis and Separating Collagens using Second Harmonic Generation and Phasor Approach to Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13378 10.1038/srep13378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reusch LM, Feltovich H, Carlson LC, Hall G, Campagnola PJ, Eliceiri KW, Hall TJ. Nonlinear optical microscopy and ultrasound imaging of human cervical structure. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:031110 10.1117/1.JBO.18.3.031110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richardson W, Clarke S, Quinn T, Holmes J. Physiological Implications of Myocardial Scar Structure. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:1877–909. 10.1002/cphy.c140067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romito E, Shazly T, Spinale FG. In vivo assessment of regional mechanics post-myocardial infarction: A focus on the road ahead. J Appl Physiol. 2017;123:728–45. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00589.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salerno M, Kramer CM. Advances in Parametric Mapping With CMR Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:806–22. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sands G, Goo S, Gerneke D, LeGrice I, Loiselle D. The collagenous microstructure of cardiac ventricular trabeculae carneae. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:110–6. 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schelbert EB, Fonarow GC, Bonow RO, Butler J, Gheorghiade M. Therapeutic Targets in Heart Failure: Refocusing on the Myocardial Interstitium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2188–98. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schenke-Layland K, Stock UA, Nsair A, Xie J, Angelis E, Fonseca CG, Larbig R, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K, Fishbein MC, MacLellan WR. Cardiomyopathy is associated with structural remodelling of heart valve extracellular matrix. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2254–65. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schipke J, Brandenberger C, Rajces A, Manninger M, Alogna A, Post H, Mühlfeld C. Assessment of cardiac fibrosis: a morphometric method comparison for collagen quantification. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122:1019–30. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00987.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinivasan A, Sehgal PK. Characterization of Biocompatible Collagen Fibers—A Promising Candidate for Cardiac Patch. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;16:895–903. 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sudarshan V, Acharya UR, Ng EYK, Meng CS, Tan RS, Ghista DN. Automated Identification of Infarcted Myocardium Tissue Characterization Using Ultrasound Images: A Review. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2015;8:86–97. 10.1109/RBME.2014.2319854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tao W, Rubart M, Ryan J, Xiao X, Qiao C, Hato T, Davidson MW, Dunn KW, Day RN. A practical method for monitoring FRET-based biosensors in living animals using two-photon microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;309:C724–35. 10.1152/ajpcell.00182.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor AJ, Salerno M, Dharmakumar R, Jerosch-Herold M. T1 Mapping: Basic Techniques and Clinical Applications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:67–81. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thimm TN, Squirrell JM, Liu Y, Eliceiri KW, Ogle BM. Endogenous Optical Signals Reveal Changes of Elastin and Collagen Organization During Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21:995–1004. 10.1089/ten.TEC.2014.0699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trivedi V, Truong TV, Trinh LA, Holland DB, Liebling M, Fraser SE. Dynamic structure and protein expression of the live embryonic heart captured by 2-photon light sheet microscopy and retrospective registration. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6:2056–66. 10.1364/BOE.6.002056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsamis A, Krawiec JT, Vorp DA. Elastin and collagen fibre microstructure of the human aorta in ageing and disease: a review. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10:20121004 10.1098/rsif.2012.1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wahyudi H, Reynolds AA, Li Y, Owen SC, Yu SM. Targeting collagen for diagnostic imaging and therapeutic delivery. J Control Release. 2016;240:323–31. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White JF, Werkmeister JA, Hilbert SL, Ramshaw JAM. Heart valve collagens: cross-species comparison using immunohistological methods. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:766–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White SK, Sado DM, Flett AS, Moon JC. Characterising the myocardial interstitial space: the clinical relevance of non-invasive imaging. Heart. 2012;98:773–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.WHO | Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [WWW Document], 2017. WHO; URL. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/. (Accessed 6 Mar 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Won S, Davies-venn C, Liu S, Bluemke DA. Noninvasive imaging of myocardial extracellular matrix for assessment of fibrosis. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013;28:282–9. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835f5a2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu X, Sun Z, Foskett A, Trzeciakowski JP, Meininger GA, Muthuchamy M. Cardiomyocyte contractile status is associated with differences in fibronectin and integrin interactions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H2071–81. 10.1152/ajpheart.01156.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zheng L, Ding X, Liu K, Feng S, Tang B, Li Q, Huang D, Yang S. Molecular imaging of fibrosis using a novel collagen-binding peptide labelled with 99 m Tc on SPECT/CT. Amino Acids. 2017;49:89–101. 10.1007/s00726-016-2328-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]