Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to examine whether reduced awareness of memory deficits in individuals with dementia is associated with more frequent need for Medicare home health care services.

Methods:

Cross-sectional analyses were conducted in a multicenter, clinic-based cohort. In total, 192 participants diagnosed with dementia and their informants were independently asked whether or not the participant demonstrated cognitive symptoms of dementia related to memory and word-finding. Participant self-awareness was measured as the discrepancy between participant and caregiver report of these symptoms. Annual Medicare home health benefit use data was obtained from Medicare claims matched by year to the Predictors study visit.

Results:

Participants that used home health services had lower awareness scores than those who did not. Awareness remained independently associated with home health use in a logistic regression adjusted for age, gender, education, caregiver relationship, global cognition, dementia subtype, and medical comorbidities.

Implications:

Reduced self-awareness of memory deficits in individuals with dementia is associated with more frequent use of Medicare home health services. The disproportionate use of in-home assistance as a function of awareness level may reflect dangers faced by patients, and challenges faced by caregivers, when patients have limited awareness of their memory deficits. Current results have implications for clinical care, caregiver education, and models of health care utilization.

Keywords: dementia, medicare, cognition, awareness, anosognosia

As of 2017, an estimated 5.5 million Americans have Alzheimer disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia. Demand for medical care increases significantly in the context of dementia,1 even before dementia incidence.2 The aggregate cost of care for patients with AD and other dementias totals an estimated $259 billion, half of which will be paid through Medicare.3 However, dementia is a highly heterogeneous condition, and symptoms can differ quite drastically from one patient to the next. Identifying the aspects of dementia that are associated with Medicare utilization is important for refining our understanding of how and why dementia affects health care use, and for developing accurate models of health care planning in dementia.

A critical feature of mild to moderate dementia particularly likely to affect health care use, and need for a home health aide specifically, is the extent to which the patient is aware of his or her cognitive and functional deficits. Reduced awareness is a frequent but not universal symptom of mild to moderate dementia4,5 present in approximately 50% of participants in these stages of the illness.6 In comparison to individuals with dementia who are aware of their cognitive and functional limitations, individuals with reduced awareness have shown poorer treatment adherence,7 decreased decision-making capacity surrounding medication management6 and driving,8 and increased engagement in risky or dangerous behaviors.9 Such behaviors are likely to lead to a greater need for formal home health aides to adequately care for these patients in the home. Moreover, disordered awareness is strongly linked to caregiver burden and distress10,11 even in the Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) stage of disease,12 further increasing the likelihood that families may seek help for such patients in comparison with those who are more aware of their cognitive and functional limitations. In addition, a recent study from Barcelona, Spain suggests that anosognosia in Alzheimer disease has been linked to increased use of informal care, which has been suggested to increase the financial burden of the disease.13

The eligibility criteria for the Medicare home health benefit are that the patient is confined to the home, and in need of skilled services.14 According to the Medicare Learning Network,15 a patient with dementia meets these criteria if they require the assistance of another person in leaving their place of residence. The home health benefit covers skilled nursing and home health aide services, which provide skilled medical services such as medication administration and management, as well as personal care such as supervision, bathing, dressing, and using the restroom. The benefit also may include medical social services, such as counseling regarding an illness, and skilled therapy services and medical equipment. In the mild to moderate stages of dementia, disordered awareness of cognitive impairment has clear implications for supervision need, but has not yet been considered in models of health care utilization, in part because it is not always measured, and is not available through Medicare claims data.

Previous work by Zhu et al16 demonstrated that increased home health care utilization among individuals with dementia, as reported by the caregiver, was associated with the patient being female, having depressive symptoms, and not living with a spouse. Scherer et al17 found that patients’ dependence level predicted home health aide use, and in particular three specific items of the Dependence Scale (needing household chores done for oneself, needing to be watched or kept company when awake, and needing to be escorted when outside). Along with awareness, we therefore examined the potential role of these various factors as well as other patient characteristics and elements of the disease that may increase need for home health (ie, medical comorbidities, overall dementia severity, global cognition, and specific cognitive symptoms). This study integrates Medicare claims data with the comprehensive clinical characterization of patients done as part of the Predictors Study to examine for the first time the extent to which disordered awareness has an independent association with home health use above and beyond these other characteristics of the patient and his or her clinical presentation.

METHODS

Sample

Data were drawn from the Predictors II cohort, a 10-year longitudinal study following participants with Probable AD and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB).18,19 Approval was received by an ethical standards committee under the Columbia Institutional Review Board, and written consent was obtained from all participants or the guardians of the participants. Participants met DSM III-R criteria for primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer type and NINDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD.20 DLB cases were diagnosed using 1996 consensus guidelines for DLB.21 Upon enrollment, all participants had a modified Mini-Mental State examination (mMMSE) score of ≥ 30, approximately equivalent to a score of 16 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).22,23 Exclusion criteria were stroke, alcoholism, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and electroconvulsive treatments.

Participants were recruited between 1997 and 2007 from Columbia University Medical Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and the Massachusetts General Hospital. Data was obtained by selecting the first study visit in which Medicare data was available. The total number of participants in the predictors II cohort was 238, but our analyses were limited to only the 192 participants who possessed full data for all covariates in our final model.

Measures

Awareness

As part of a separate questionnaire developed for the Predictors study, participants and caregivers answered questions in which they endorsed the presence (1) or absence (0) of 4 specific cognitive difficulties in the preceding 2 weeks. Two of these capture hallmark symptoms of Alzheimer-type dementia:24,25 (1) “Do you repeat the same question over and over again?” and (2) “Do you have trouble finding the right word when speaking?” Participants’ responses to these 2 items were summed, as were caregivers’ responses regarding participants’ abilities. A discrepancy score was calculated by subtracting the caregiver’s score from the participant score, which yielded values that ranged from −2.0 to 2.0. More negative scores indicate reduced participant awareness of symptoms, and a score of 0 suggests no discrepancy between participant and caregiver report. Positive scores indicate participant over-endorsement of symptoms as compared to caregivers.

Cognition

The modified Mini Mental State Exam (mMMSE) was used to measure global cognition. Verbal memory was assessed with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT),26 a 12-word, 3-trial list learning task. Delayed recall was tested 20 to 30 minutes after initial recall trials. The outcome measure was the percentage of words retained at delayed recall (% retention). Word retrieval was assessed with 2 separate scores including: (1) the Boston Naming Test27 and (2) performance on phonemic and semantic fluency tests in which participants had 60 seconds to name words that begin with a specific letter (C, F, or L) or that belong to a specified semantic category28 respectively. A verbal fluency index was created by combining phonemic and semantic fluency.

Depression

Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory29 for depression, comprising 7 questions asking if the participant felt lonely, blue, hopeless, worthless, easily hurt, had no interest in doing things, and/or was considering ending their life. Participants could respond with “Not at all” (1), “A little bit” (2), “Moderately” (3), “Quite a bit” (4), and “Extremely” (5), producing a range of 7 to 35 for the entire measure, with higher score indicating higher depressive symptoms.

Medical Comorbidities

The Charlson Comorbidity Index30 was used to assess medical comorbidities that may affect utilization of Medicare benefits. Comorbidities were measured at each study visit, and included myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal diseases, liver disease, arthritis, diabetes, chronic renal disease, and systemic malignancy. For this study, comorbidities were taken from the first visit for which Medicare data was available. All items received weights of one, with the exception of chronic renal disease and systemic malignancy, which received a weight of 2. Charlson scores were trichotomized at each visit and averaged across all available visits to capture overall level of co-morbid disease while followed during the study. The score ranges from 0 to 2, with higher scores indicating heavier comorbidity burden.

Dementia Severity

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale31 is a 5-point measure used to stage dementia that summarizes functional ability across six domains of functioning: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. Dementia severity in our sample ranged from very mild (0.5) to mild to moderate (2). Dementia subtype was coded as probable AD or DLB.

Home Health Use from Medicare Data

Medicare utilization data from the participant’s first visit year were obtained from Medicare Standard Analytic files through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The primary outcome of interest was home health use, which was derived from home health claims by skilled-nursing care, home health aides, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and medical social services.

Analysis

Annual Medicare usage data were aligned with clinical data from the Predictors II study according to the visit year. A Spearman’s correlation was conducted to examine the validity of caregivers reports against objective memory performance. Cross-sectional analyses were conducted for each participant at the earliest instance in which both Medicare and awareness data were available for each participant. Spearman correlations (ρ) were used to compare predictors of awareness and Medicare use. A 1-way ANOVA was used to examine mean awareness level as a function of home health benefit use (yes/no). An adjusted logistic regression was used to examine the extent to which awareness predicted home health use, controlling for relevant covariates including gender, education, medical comorbidities, age, diagnosis subtype, mMMSE, Clinical Dementia Rating, and caregiver relationship. Finally, in order to identify the most useful awareness score for predicting who did and did not use home health aides, we conducted ROC curve analyses.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics can be found in Table 1. Participants were clinically diagnosed with Probable AD (89.1%) or DLB (10.9%). 56.0% were female and 92.7% identified as white. The average age was 78.2 (SD = 6.8) and average years of education were 14.46 (SD = 2.93).

TABLE 1.

Participant Demographic and Disease-related Variables: Descriptive Statistics

| Sample (N = 192) |

Home Health Users (N = 20) |

Non Home Health Users (N = 172) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Awareness | −0.37 | 0.85 | −2 to 2 | −0.8* | 0.62 | −0.32* | 0.86 |

| Age | 78.23 | 6.80 | 58.10−94.99 | 81.07* | 7.24 | 77.89* | 6.69 |

| CDR† | 1.05 | 0.28 | 0.5−2 | 1.20* | 0.41 | 1.03* | 0.26 |

| Education | 14.45 | 2.93 | 7‒20 | 13.90 | 2.69 | 14.52 | 2.96 |

| Medical Comorbidities‡ | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0−2 | 0.97* | 0.79 | 0.64* | 0.67 |

| Global Cognition§ | 21.17 | 4.49 | 7−30 | 19.20* | 4.59 | 21.37* | 1.028 |

| N per group | N per group | N per group | |||||

| Diagnosis Subtype‖ | 172 AD/20 DLB | 15 AD/5 DLB | 157 AD/15 DLB* | ||||

| Gender | 84 male/108 female | 10 male/10 female | 74 male/98 female | ||||

Clinical dementia rating: 0 = Healthy, 0.5 = Very Mild, 1 = Mild, 2 = Moderate.

Charlson comorbidity index.

Modified Mini Mental Status Exam.

Dementia subtype.

P < 0.05 indicates significant difference between home health groups.

AD indicates probable Alzheimer disease, DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies.

Caregivers tended to be the spouses (50.5%) or children (38.5%) of the participants, rather than friends or other relatives (10.9%). In total, 63.9% of participants lived with their caregiver. Caregivers who lived with the participant were more likely to be their spouses (77.9%) than their children (14.8%) or other relatives, friends, and siblings (7.4%) [χ2(2, N = 191) = 101.452; P < 0.001]. Participants who did not live with their caregivers primarily lived alone at home (68.1%), rather than at a nursing home (18.8%), assisted living facility (7.2%), retirement home (4.3%) or other (1.4%).

The mean awareness score for the sample was −0.369 (SD = 0.852), which was significantly different from 0 [t(191) = −6.012; P < 0.001; d = −0.435], indicating that on average, participants significantly underreported their difficulties as compared to their caregivers. Caregiver reports were significantly associated with objective memory performance as measured by the HVLT [ρ = −0.185; P = 0.016; d = 0.386].

Correlates of Awareness

Awareness, as measured by the discrepancy score, was not related to gender, [t(190) = 0.522; P = 0.602; d = 0.037], CDR [F(2,191) = 0.288; P = 0.750], dementia subtype [t(190) = −0.941; P = 0.348; d = 0.068], age [ρ(192) = −0.1; P = 0.186], or education [ρ(192) = −0.03; P = 0.726]. In contrast, participant depression was positively correlated with awareness [ρ(190) = 0.15; P = 0.035].

With regard to cognition, awareness was correlated with mMMSE [ρ(190) = 0.17; P = 0.020] but not with memory as measured by percent retention of the HVLT [ρ(171) = 0.04; P = 0.585], or word retrieval as measured by either the Boston Naming Test [ρ(154) = 0.16; P = 0.054], or the composite verbal fluency index [ρ(152) = 0.02; P = 0.783]. Between 11.4% and 22.3% of entries were missing from each cognitive assessment, because of historical differences in test batteries and opt-outs. However, in no case were the proportions of opt-outs associated with awareness (P = 0.288).

Finally, awareness did not differ based on caregiver relationship to the participant [F(2,191) = 0.367; P = 0.693], or participant living situation [F(1,191) = 0.834; P = 0.362].

Correlates of Home Health Use

Of 192 participants, 20 used the home health benefit while 172 did not. Participants who used the home health benefit had a significantly lower awareness score (M = −0.80, SD = 0.615) than those who did not (M = −0.319, SD = 0.863) [t(190) = 2.415; P = 0.017; d = 0.175]. Individuals who used the home health benefit also had lower mMMSE [t(190) = 2.06; P = 0.041; d = 0.149], were older [t(190) = −1.988; P = 0.048; d = −0.144], had more medical comorbidities [t(190) = −1.989; P = 0.048; d = −0.144], greater dementia severity [t(190) = −2.488; P = 0.014; d = −0.180], and were more likely to have a diagnosis of DLB [χ2(1, N = 192) = 5.088; P = 0.024]. In contrast, home health benefit was not associated with gender (P = 0.551), education (P = 0.374), or depression (P = 0.972).

Certain caregiver variables, such as caregiver relationship were also associated with home health use. Specifically, participants who used the home health benefit were more likely to have children as their caregivers (55%) than spouses (25%) or other relatives, siblings or friends (20%) [χ2(2, N = 192) = 6.124; P = 0.047]. Whether or not the caregiver was living with the participant was not a factor in the use of the home health benefit [χ2(1, N = 192) = 1.918; P = 0.166], nor was if they lived at home versus living in a retirement home, assisted living facility or nursing home [χ2(1, N = 192) = 0.072; P = 0.789].

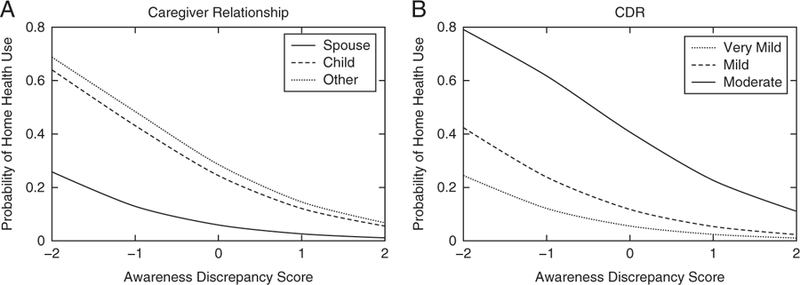

A logistic regression was performed to examine the extent to which level of awareness had an independent association with use of the home health benefit, above and beyond relevant variables including: age, medical comorbidities, global cognition, dementia severity, dementia subtype, gender, education, and relationship of caregiver to participant. Because depression was not associated with home health use, it was omitted from the final model. The model was statistically significant, [χ2(10) = 27.576; P = 0.002], correctly classified 90.7% of cases, and explained 27.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in the use of home health services. Wald tests demonstrated that awareness (β = −0.853, P = 0.020), dementia severity (β = −1.638; P = 0.039), and having the child of the participant as the caregiver (β = 1.631, P = 0.029) were the only significant contributors to the model. A hierarchical model comparison was made between a model including all the variables, and a second model that omitted awareness. Awareness significantly improved the model [χ2(1) = 6.082; P = 0.014], and its inclusion accounted for 5.7% (Nagelkerke R2) of the total variance. Figure 1 depicts marginal model predictions of awareness on home health use stratified by caregiver relationship and dementia severity (Table 2). The correlations among predictors were assessed, correcting for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Bonferroni step-down procedure.32 Results suggest that none of the correlations between coefficients were sufficiently large to merit serious concern regarding multicollinearity. Further details can be found in the supplementary materials (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CLINSPINE/A75). In addition, we conducted ROC curve analyses to explore whether the awareness metric could significantly distinguish between the 2 groups (used home health/did not use home health) above chance, and found that it did (AUC = 0.657; SE = 0.056; P = 0.02; 95% CI = 0.548 to 0.766). Using Youden’s index, we found that the threshold of an awareness score <−1 demonstrated the best balance of sensitivity and specificity, suggesting that awareness discrepancy scores at or below −1 significantly predict home health use.

FIGURE 1.

Logistic Regression: Probability of home health use given awareness score and average covariates. Logistic fits predicting probability of home health use as a function of awareness discrepancy score, given average scores of other model covariates. A, Estimates given spouse (solid line), child (dashed line), and other (dotted line). B, Estimates given Clinical Dementia Ratings of very mild (dotted line), mild (dashed line), and moderate (solid line).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Home Health Benefit Use (N = 192) Controlling for Relevant Variables

| Home Health Use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | OR (95% CI) |

| Awareness | −0.853* | 0.366 | 0.426 (0.207–0.877) |

| Sex† | 0.896 | 0.635 | 2.450 (0.700–8.576) |

| Education | 0.004 | 0.099 | 1.004 (0.826–1.220) |

| Medical comorbidities | 0.574 | 0.374 | 1.776 (0.848–3.713) |

| Age | 0.020 | 0.44 | 1.02 (0.428–2.431) |

| Global cognition | 0.008 | 0.068 | 1.008 (0.881–1.153) |

| Diagnosis‡ | −1.336 | 0.751 | 0.263 (0.059–1.157) |

| CDR | 1.638* | 0.791 | 5.142 (1.080–24.502) |

| Child caregiver§ | 1.631* | 0.748 | 5.107 (1.168–22.352) |

| Other caregiver§ | 1.844 | 0.954 | 6.322 (0.962–41.529) |

| Constant† | −7.024 | ||

| χ2 | 27.576** | ||

| df | 10 | ||

Male as reference.

DLB as reference.

Spouse caregiver as reference.

OR indicates odds ratio, calculated as exponentiated B; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of OR point estimate.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which awareness of memory deficits is associated with Medicare home health use, and to determine if awareness adds unique information above and beyond other predictors of this Medicare service. Our results supported the hypothesis that reduced awareness was associated with higher probability of Medicare home health care use, even after controlling for age, gender, education, dementia severity and subtype, medical comorbidities and caregiver relationship. This is the first study to demonstrate the relevance of reduced awareness for health care utilization, and has implications for modeling the cost of dementia as well as educating families and caregivers.

In addition to its association with home health use, we observed that reduced awareness was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, consistent with most previous studies.33 In addition, reduced awareness was associated with lower global cognition, but not with disease severity or any of the specific aspects of cognition assessed including memory, executive function or language abilities. Although awareness would be expected to relate to disease severity over the course of the entire disease spectrum, the lack of association between awareness and CDR in the current and other studies of mild to moderate disease is consistent with the idea that disordered awareness is not simply a marker for more severe disease or specific cognitive dysfunction.34 Indeed, some proposals suggest that unawareness might reflect compromise to one or more cognitive processes specific to self-evaluation (ie, metacognition).34 Awareness was also not associated with the measured caregiving variables, suggesting that the caregiver-based awareness discrepancy score operated in a similar way across caregivers regardless of their relationship to the patient, or whether they lived with the patient. Taken together, findings from the regression as well as the bivariate analyses support the idea that disordered self-awareness is an important phenotype in its own right, and should thus be considered explicitly in patient care, caregiver education, and models of health care utilization.

The exact mechanisms by which awareness is linked to home health use were not examined in this study; however, we hypothesize that caring for a patient who is not aware of their symptoms brings unique challenges and may lead caregivers to opt to utilize the Medicare home health benefit more readily, either as a function of increased burden, or as a means of keeping the patient safe. Indeed, disordered awareness of disease symptoms has been linked to increased caregiver burden,11,35 which has also been associated with increased caregiver health care use and caregiver health outcomes such as depression.36 Some proportion of this burden is likely to be attributable to impairments in patient decision making that accompany disordered awareness of one’s memory deficits. For example, patients who are unaware may be less willing or able to manage their health care needs, such as attending appointments and accessing clinical services. As a result, caregivers may need to rely more heavily on home health aide services. In addition, patients with reduced awareness are more likely to engage in dangerous behaviors37 and are less likely to modify their approach to a range of cognitively demanding activities that may have negative functional outcomes, such as driving or cooking.9,38 Moreover, associations have been shown between disordered awareness and reduced decision-making capacity regarding taking a hypothetical medication for memory loss,6 and managing medication.7

From a clinical perspective, current findings suggest that awareness of cognitive deficits should always be assessed carefully, and addressed explicitly with caregivers. Caregivers should be educated on disordered awareness as a distinct symptom of dementia, separate from other cognitive impairments, and should be counseled in how to cope both emotionally and strategically. Caregivers might be better able to tackle the consequences of unawareness if they can be understood as outside of the patient’s control. Future research should examine if early educational trainings and/or early implementation of home health services directly improves not only patient outcomes such as safety, but caregiver outcomes such as burden in the context of disordered awareness.

Finally, we also examined other correlates of home health use apart from awareness. As may have been expected, these included older age, worse global cognition, and greater burden of medical comorbidities. Interestingly, having a diagnosis of DLB was also associated with home health use. This association may reflect the fact that DLB is characterized by motor and psychiatric features, in addition to cognitive changes, that may increase functional impairments and thus need for additional care.39 Lastly, having a child as a caregiver, as opposed to a spouse or a friend, was also associated with increased home health use. These results are broadly consistent with the previously reported finding that self-reported use of caregiving services is associated with the patient not living with the spouse.16 Younger caregivers may have competing priorities such as raising children and working, and may not have the time to commit to caregiving to the extent that they feel is appropriate. It is also possible that children of participants experience increased burden given these competing responsibilities. In fact, caregiver age has been inversely correlated with both guilt and clinically characterized caregiver burden.40 Understanding which type of caregivers are most likely to require home health assistance has implications for caregiver education and models of service utilization.

This study has several limitations. Future investigation of this topic would benefit from a more detailed awareness diagnostic, as our measurement was not a standardized measure of awareness. However, using informant’s reports as a “gold standard” is a common way of measuring awareness, and this is also supported by our results (eg, informant reports were associated with patients’ actual memory performance). Also of interest would be the relationship between awareness and informal caregiving or private-paid home health services, to expand beyond this study’s focus on the Medicare home health benefit. Additionally, in a larger dataset, it would be very interesting to further investigate the awareness metric by testing for differences in predictive power at each level of awareness. However, given our sample size, this question would have to be resolved through future studies. Although this study provides an objective measure of use among Medicare recipients, obtaining the benefit requires that patients meet the eligibility criteria, raising the bar to entry. In addition, many dementia caregivers underutilize care resources, such as Medicare, because of not knowing of their availability or how to access them.41 Finally, our participants were drawn from tertiary care university hospitals and specialized AD clinics, rather than a community-based sample. Our sample thus tended to be predominantly white and highly educated. The study should be replicated in participants of other ethnicities or with lower education, as our ability to generalize the findings is limited.

Nonetheless, this study has important strengths, most notably the integration of real world Medicare usage with carefully clinically characterized individuals. Synthesis of these distinct data sets enables examination of complex phenotypes that are not otherwise available through Medicare data files. We conclude from the current analyses that participants who present with disordered awareness of disease symptoms in dementia are more likely to require, or at least use, the Medicare home health benefit. This increased used is likely to reflect the psychological and practical effects of caring for an individual with dementia who is unaware of their cognitive limitations. Such individuals are more likely to attempt to engage in cognitively demanding activities which are beyond their cognitive capacity, thus threatening their safety, placing stress on the caregiver, and likely increasing patient frustration. Taken together, these experiences can drive the need for home health assistance even at a relatively mild stage of disease. Our results suggest that the reduced awareness of symptoms is of particular importance in determining the needs of patients and caregivers, and awareness is an important variable to consider in models of service utilization. Future work should more directly examine the interplay between patient awareness, patient decision making, caregiver relationship, caregiver burden, and health care utilization to map out the precise pathways between these variables.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Aging, grant # R01 AG007370.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.alzheimerjournal.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Ornstein K, et al. Use and cost of hospitalization in dementia: longitudinal results from a community-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30: 833–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare utilization and expenditures around incident dementia in a multiethnic cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70:1448–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:325–373. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1993;15:231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ott BR, Lafleche G, Whelihan WM, et al. Impaired awareness of deficits in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1996;10:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosentino S, Metcalfe J, Cary MS. Memory awareness influences everyday decision making capacity about medication management in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2011; 9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arlt S, Lindner R, Rösler A, et al. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging 2008;25:1033–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotrell V, Wild K. Longitudinal study of self-imposed driving restrictions and deficit awareness in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999;13:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wild K, Cotrell V. Identifying driving impairment in Alzheimer disease: a comparison of self and observer reports versus driving evaluation. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBettignies BH, Mahurin RK, Pirozzolo F. Insight for impairment in independent living skills in Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1990; 12:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seltzer B, Vasterling JJ, Yoder J, et al. Awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to caregiver burden. Gerontologist 1997;37:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelleher M, Tolea IT, Galvin JE. Anosognosia increases caregiver burden in mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:799–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turro-Garriga O, Garre-Olmo J, Rene-Ramirez R, et al. Consequences of anosognosia on the cost of caregives’ care in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;54:1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medicare Learning Network Booklet. The Medicare Home Health Benefit. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (online) Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Medicare-Home-Health-Benefit-Text-Only.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2016.

- 15.Medicare Learning Network Matters. Home health – Clarification to benefit policy manual language on “Confined to home” definition Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM8444.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2016.

- 16.Zhu CW, Torgan R, Scarmeas N, et al. Home health and informal care utilization and costs over time in Alzheimer’s disease. Home Health Care Serv Q 2008;27:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherer R, Scarmeas N, Brandt J, et al. The relation of patient dependence to home health aide use in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol Series A 2008;63:1005–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards M, Folstein M, Albert M, et al. Multicenter study of predictors of disease course in Alzheimer disease (the “predictors study”). II. Neurological, psychiatric, and demographic influences on baseline measures of disease severity. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1993;7:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern Y, Folstein M, Albert M, et al. Multicenter study of predictors of disease course in Alzheimer disease (the “predictors study”). I. Study design, cohort description, and intersite comparisons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1993;7:3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA Work Group, under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKeith IG, Galasko K, Kosaka EK, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996;47:1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein M, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”.A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stern Y, Sano M, Paulson J, et al. Modified mini-mental state examination: Validity and reliability. Neurology 1987;3(suppl 1): S179. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark LJ, Gatz M, Zheng L, et al. Longitudinal verbal fluency in normal aging, preclinical, and prevalent Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2009;24:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKhann G, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association work-groups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disase. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt J The hopkins verbal learning test: development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin Neuropsychol 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams BW, Mack W, Henderson W. Boston naming test in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 1989;27:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen WG. Verbal fluency in aging and dementia. J Clin Neuropsychol 1980;2:135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cines S, Fearell M, Steffener J, et al. Examining the pathways between self-awareness and well-being in mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;23: 1297–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindbrook J Multiple comparison procedures updated. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1998;25:1032–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cosentino S Metacognition in Alzheimer’s Disease. In: Fleming SM, Frith C, eds. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition New York, NY: Springer; 2014:389–407. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rymer S, Salloway S, Norton L, et al. Impaired awareness, behavior disturbance, and caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disor 2002;16:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Ornstein K, et al. Health-care use and cost in dementia caregivers: Longitudinal results from the Predictors Caregiver Study. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, et al. Insight and danger in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaked D, Farrell M, Huey E, et al. Cognitive correlates of metamemory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 2014; 28:695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ricci M, Guidoni SV, Sepe-Monti M, et al. Clinical findings, functional abilities and caregiver distress in the early stage of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;49:e101–e104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Springate BA, Geoffrey T. Dimensions of caregiver burden in dementia: impact of demographic, mood, and care recipient variables. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:294–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwyther LP. Overcoming barriers. Home care for dementia patients. Caring 1989;8:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]