Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of the study was to determine the radiation dose reduction achieved when rectangular collimation was used on various round collimators. In addition, we evaluated the tissue doses imparted to various head and neck organs.

Methods:

To evaluate the variation in radiation output based on the variable geometric configurations, the kerma area product (KAP) was measured using a commercially available KAP-meter with an internal ion chamber capable of detecting both radiation dose (µGy) and the primary X-ray beam area. The KAP was measured using standard 20.4, 25.7, and 31.7 cm2 round collimators with and without rectangular X-ray field restrictors. To evaluate the potential change in patient scatter radiation dose, an adult head phantom was loaded with thin strips of gafchromic film. A full mouth X-ray series was acquired with various geometric configurations. The films were quantified using a calibration factor to yield absorbed organ doses for the eyes, thyroid, and salivary glands.

Results:

With the use of rectangular collimator, the KAP for a 31.7 cm2 round collimator was reduced by up to 60% while the 20.4 cm2 round collimator elicited a reduction from up to 40%. In the organ study, results of up to 81% reduction in scatter radiation dose were observed.

Conclusions:

Although, US FDA regulations allow a maximum beam size of 38.5 cm2 on the patient skin, this study suggests that the use of rectangular collimators provide clinically relevant dose reduction for patients, even when using smaller round collimation, hence the use of rectangular collimation for all intraoral radiographic procedures is highly recommended.

Keywords: collimation, dose, kerma air product, rectangular collimation, scatter, round collimation

Introduction

In 1995, federal regulations promulgated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated that the primary X-ray beam not exceed the size of the image detector in all other areas of medical radiography.1 The American Dental Association, in collaboration with the FDA published an article on dental radiography guidelines, which includes a collimation recommendation of the rectangular shaped collimation usage over round collimation.2 The continued practice of mismatched collimation to detector geometry in dental intraoral radiography causes the dental imaging community to be inconsistent with the medical imaging community at large.

In 2004, the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement (NCRP) released a recommendation stating, “rectangular collimation of the X-ray beam shall be routinely used for periapical radiography”.3 The report also went on to specify that the size of the primary X-ray beam at the distance of the intraoral detector should not be in excess of the dimension of the detector by greater than 2% of the source-to-image distance. In fact as early as 1984, Gibbs et al suggested that patient risk could be reduced by almost 64% changing from a 7 cm round beam to a rectangular collimator.4

The need for awareness of radiation exposure in dentistry is due to the potential unknown effects of cumulative radiation doses during intraoral radiography performed throughout a patient’s lifetime care, particularly due to the frequency of these examinations beginning in early childhood when organs such as the thyroid are thought to be more susceptible to the effects of radiation than in later adulthood.5

Although, a number of previously published studies on dental radiography have investigated the thyroid dose reduction between round vs rectangular collimation,6–8 dose reduction calculations using three commercially available round collimators (20.4, 25.7, and 31.7 cm2) was not done. Previous results were not surprising given the radiosensitivity of the thyroid as reported by the NCRP, the National Research Council’s Committee to Assess Health Risks from Exposures to Low Level Ionizing Radiation, and International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP).3,9–11 However, it is not the only radiosensitive organ exposed to primary or secondary radiation during intraoral radiography.

For example, acute radiation exposure has also been shown to produce cataracts at a threshold of 500 mGy absorbed dose to the lens of the eye.12 Non-stochastic detrimental effects to the lens of the eye have become of particular interest recently with the latest commentary from the NCRP recommending a reduction of the occupational radiation dose limit from 150 to 50 mGy per annum based on review of the current literature.13 These organ dose limits would not apply to medical exposures, since the use of radiation in medicine is at the discretion of the qualified practitioner. It does suggest that there are additional radiosensitive organs, such as the eyes (which cannot be easily shielded during intraoral exposures), that reasonable efforts should be made to reduce radiation doses to those organs.

Reducing the primary beam size to the detector field of view reduces the unnecessary radiation exposure to non-imaged tissue. This is particularly important when exposing radiosensitive tissue in the head and neck that do not provide any diagnostic image data pertinent to the exam. Additionally, of concern is the amount of secondary scatter radiation produced during an exposure. As the primary beam decreases in size, the size of the tissue irradiated decreases, thus causing the secondary scatter radiation within the tissue to decrease in some relative quantity as well. Radiographic examinations should only be performed when there is a net benefit to the patient after a thorough history and physical as well as clinical inspection. The examination should be justified and the dose should be as low as reasonably achievable, all based on sound fundamental radiation protection principles outlined by ICRP.11 The costs of rectangular collimator are negligible and since a significant reduction of radiation dose was demonstrated as a benefit to the patient,14 the practice of rectangular collimation should be mandated by the national regulatory boards.

This study evaluates the relative quantity of organ dose reduction in three types tissues in the head and neck by simply combining the reduction in the primary beam field of view and secondary radiation scatter when using a rectangular collimator vs the traditional round collimation.

Methods and materials

Kerma area product

Three commercially available intraoral X-ray imagers were selected for this study that were located within the clinics of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine. The Progeny Preva (Midmark, Lincolnshire, IL, USA) with a 31.7 cm2 round collimator, a Bel Ray 096 (Takara Belmont Corp., Osaka, Japan) with a 25.7 cm2 round collimator, and a Carestream CS 2200 (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA) with a 20.4 cm2 round collimator. A removable universal rectangular collimator (Dentsply Rinn, York, PA,USA) with a 12.0 cm2 area was installed on the two larger intraoral systems for the comparison of round to rectangular collimation. The Carestream round collimation was too small for the universal rectangular collimator, so the manufacturer’s 12.0 cm2 removable rectangular collimator was used instead. It is important to note that based on differences in X-ray tube output the absolute primary and scatter radiation measurements cannot be compared directly, but rather the magnitude of reduction is comparable since this is a direct consequence of the change in the geometry of the primary beam and not variable intraoral X-ray system techniques.

Variation in radiation dose based on the geometric reduction of the primary X-ray beam from round to rectangular is most easily observed through a metric such as the KAP. KAP is a measure of the energy imparted to air by ionizing radiation over entire physical area of the X-ray field. It is the appropriate measurement for total radiation incident on the patient’s skin and is an indication for the total amount of radiation imparted during the examination.

A Patient Dose Calibrator (PDC, Radcal, Monrovia, CA) with a linear response (±3%) for X-ray tube voltages ranging from 40 to 150 kVp and a 0.01 µGy-m2 minimum detectable KAP was employed for the KAP measurements. The calibrated PDC has a manufacturer specified accuracy of ±10%. The round and rectangular collimators were placed in contact with the PDC for each measurement as shown in Figure 1. A series of 10 measurements were made for each condition set to evaluate the hypothesis that the relative KAP remains consistent for variable X-ray techniques such as tube voltage and tube current–time product, and varies with respect to changes in the primary beam geometry. The measured KAP are free in air; therefore, the resulting data are not tissue specific.

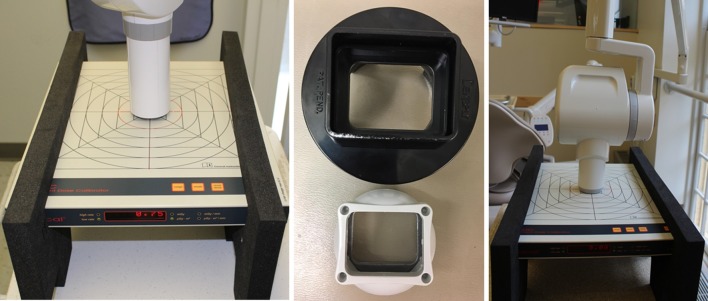

Figure 1.

The experimental setup with collimator placed in contact with the PDC for KAP measurements, and the Dentsply and Carestream rectangular primary beam limiters installed for these measurements. KAP, kerma area product; PDC, patient dose calibrator.

Head phantom organ dose

To study patient organ dose reduction from scatter radiation as a factor of geometric collimation changes, a tissue equivalent adult head CIRS Atom® phantom (Computerized Imaging Reference Systems Inc., Norfolk, VA) was implanted with thin strips of Gafchromic film (Ashland, Bridgewater, NJ) in the 0.5 cm dosimetry pre-drilled holes in the appropriate 2.5 cm thick slabs corresponding to the level of the eyes, salivary glands, and thyroid as seen in Figure 2. Film dosimeters were chosen for their flexible positioning and sensitivity in the diagnostic X-ray imaging tube voltage range of 20–200 kVp. The sensitivity of the dosimetry film is 1–200 mGy for this energy range.

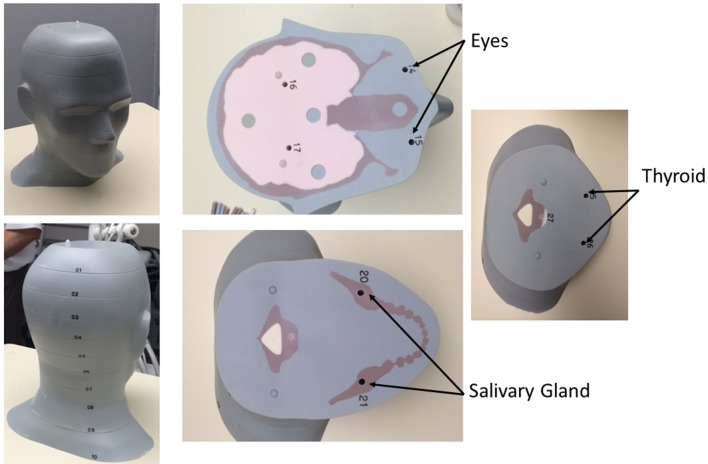

Figure 2.

The adult phantom head used with individual slices and simulated organ locations marked numerically with corresponding wells for Gafchromic film placement.

Calibration of the Gafchromic film was conducted using a calibrated solid-state radiation detector (Black Piranha, RTI, Towaco, NJ). A second order polynomial (R2 >0.988) calibration curve was fit to the mean green value of each calibrated filmstrip and its associated radiation absorbed dose (0.76–51 mGy). An unexposed filmstrip was also scanned to establish the mean green value corresponding to a null exposure for extrapolation of data for 0–0.76 mGy. This calibration curve and fit parameters were used to translate the measured mean green values from each implanted filmstrip to an organ dose value. A commercially available flatbed scanner was used to scan each filmstrip in a manner identical to the scanning of the calibration film. The mean green values across multiple sampling points (n > 87) in each filmstrip were analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). An average of the mean green values for each tissue location was used to compare the organ dose change between the round and rectangular collimation.

For simplicity, the technique factors such as X-ray tube voltage (kVp) and tube current-time product (mAs) were held constant (Table 1) as the collimation was varied from round to rectangular for each intraoral unit. For positioning purposes, an experienced dental radiology staff member assisted in replicating a full mouth series procedure on the adult phantom head that simulated a typical clinical scenario. The tube head angles for each image were documented for accuracy and replicative purposes.

Table 1. .

Various collimator sizes and configurations along with tube voltages and tube current-time products used in the study

| Intraoral imager | Round diamete r(cm) | Round area (cm2) | Rectangular area (cm2) | Tube voltage (kVp) | Tube current (mA) |

| ProgenyPreva | 6.4 | 31.7 | 12.0 | 60 a /70 | 7 |

| Bel Ray 096 | 5.7 | 25.7 | 12.0 | 70 a | 10 |

| CarestreamCS2200 | 5.1 | 20.4 | 12.0 | 60 a /70 | 7 |

Denotes the tube voltage used for patient organ dose.

Since the sensitivity of the Gafchromic film at the clinical tube voltage is 1–200 mGy and the calibration curve were both in the mGy range multiple exposures were required to gain sufficient data on the filmstrips from the scatter radiation. Therefore, we performed serial exposures for each view of the full mouth series for two sets of film per implanted location. The cumulative tube current-time product ranged from 233 to 620 mAs for the 12 data sets. This yielded scatter radiation doses in the sensitivity range of the film and absorbed dose conversion curve. To yield a scaled absorbed organ dose that would be useful within the context of clinical imaging parameters the absorbed dose was scaled by the cumulative tube current-time product (mAs) for each full mouth series and expressed as µGy per mAs.

Results

Kerma area product

A series of 10 measurements were taken for each condition set with the PDC on the three selected intraoral radiographs. All condition sets were completed in both the round and rectangular collimation. Two condition sets were added that varied the tube voltage and the tube current–time product (mAs). These condition sets were added to ensure the relative KAP was unaffected by variations in the X-ray tube technique when identical techniques were set for both the round and rectangular collimation KAP measurements. The Progeny and Carestream intraoral units had variable peak tube voltage (kVp), so one condition set was measured at 60 kVp in both the round and rectangular collimators and another condition set was at 70 kVp. For the Bel Ray with a fixed peak tube voltage the tube current–time product (mAs) was varied to create two additional condition sets at 2.4 and 4.1 mAs in both collimator configurations. The absolute KAP measurements are not directly comparable, as the output for each system was not regulated to account for manufacturing differences between the units. However, the relative KAP reduction is comparable between the units since identical technique factors were used in the round vs rectangular collimation for measurements within each intraoral X-ray system.

Table 2 provides both the measured KAP and relative KAP reduction as a function of each condition set. The variable tube voltage condition set showed a <1% difference in the relative KAP reduction at 60 vs 70 kVp. Additionally the variable tube current–time product condition varied from 2.4 to 4.1 mAs and showed <1% difference between the relative KAP reduction for the two beam geometries. Thus showing the KAP reduction is dependent on primary beam geometry with only minor variations for technique adjustments of the tube voltage or tube current–time product. Standard deviation was assessed for all KAP measurements sets with an average standard deviation of 0.02 and maximum of 0.05 µGy-m2. The relative KAP reduction followed suit with the geometric reduction. In the largest primary beam geometric reduction of 62% from round to rectangular, the relative KAP reduced up to 60%. The same occurred for the 53 and 43% geometric reductions resulting in relative KAP reductions of 54 and 40% respectively.

Table 2. .

The KAP results for all three intraoral units at various tube currents and tube current–time products for the various round vs rectangular collimation condition sets

| Collimation | Area (cm2) | Tube voltage (kVp) | Tube current- time product (mAs) | KAP(µGy-m2) | KAP reduction |

| Round | 31.7 | 60 | 2.4 | 5.08 ± 0.01 | 0.60 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 2.04 ± 0.05 | |||

| Round | 31.7 | 70 | 2.4 | 7.20 ± 0.03 | 0.59 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 2.96 ± 0.02 | |||

| Round | 25.7 | 70 | 2.4 | 4.52 ± 0.02 | 0.54 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 2.08 ± 0.01 | |||

| Round | 25.7 | 70 | 4.1 | 8.13 ± 0.02 | 0.54 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 3.71 ± 0.01 | |||

| Round | 20.4 | 60 | 2.4 | 5.73 ± 0.03 | 0.39 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 3.48 ± 0.01 | |||

| Round | 20.4 | 70 | 2.4 | 7.64 ± 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Rectangular | 12.0 | 4.61 ± 0.02 |

KAP, kerma area product;

Head phantom organ dose

A full mouth X-ray series was performed using each of the three intraoral X-ray systems on both the standard round collimation and with an attachable rectangular collimator. Since the radiation output of each tube was not held constant between the three systems, all direct organ dose comparisons are made within each manufacturer data set (round vs rectangular collimation). A Mann Whitney test was used to determine statistical significance of the equivalence of the medians. The data was scaled to an organ dose (µGy) per tube current-time product (mAs) for each collimation and is presented in Figure 3 by intraoral system.

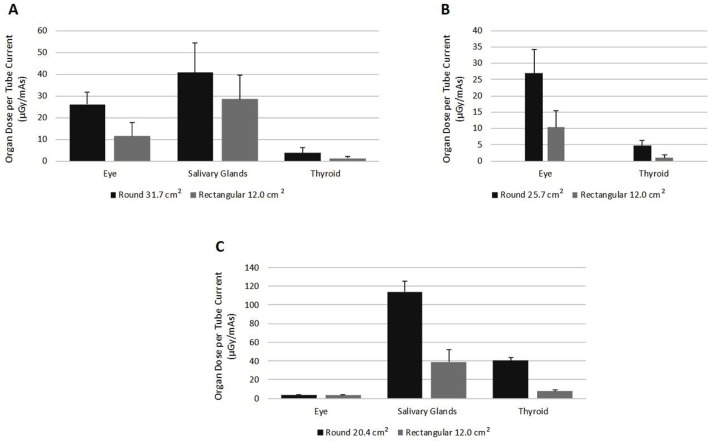

Figure 3.

The results from the scatter radiation dose for head and neck organs in the (A) 31.7 cm2, (B) 25.7 cm2 and (C) 20.4 cm2 round collimations versus the 12.0 cm2 rectangular collimation.

The two largest round collimations (31.7 cm2 Progeny Preva and 25.7 cm2 Bel Ray 096) show decreases in organ dose for all organs listed. The largest round collimation (Figure 3A) showed the largest reduction to the thyroid with a reduction of 66% (p<0.05) in the radiation scatter organ dose on the films when the rectangular collimation was used to further reduce the 31.7 cm2 round collimation of the primary beam. Also, in the 31.7 cm2 round collimation the filmstrips at the level of the salivary glands showed a reduction of 30%. However, the standard deviation was significant in relation to the measured values and was determined to not be of statistical significance (p > 0.05).

The middle 25.7 cm2 round collimator on the Bel Ray 096 was used to investigate the organ dose change in the eyes and thyroid only. Investigation at the level of the salivary glands was completed only for the largest and smallest round collimators. Both the eyes and thyroid showed a decrease of 62% (p < 0.01) and 81% (p < 0.01) when the rectangular collimator was employed (Figure 3B).

The smallest round collimation of 20.4 cm2 (Carestream CS 2200) showed scatter radiation dose reduction most strikingly in the thyroid (81%; p < 0.05) (Figure 3C). There was a slight increase seen in the eye dose with the rectangular collimation (3.32 vs 3.47 µGy mAs–1), however, this was a statistically insignificant finding (p > 0.05) (Figure 3C). The eye organ dose values are within one standard deviation of each other and suggest that these values are statistical variants of image noise in the films rather than a true increase. The findings at the level of the salivary glands suggested that a radiation scatter organ dose reduction of 66% (p < 0.05) was achieved with rectangular collimation.

Gafchromic Film locations in the mandible were chosen for the largest and smallest round to rectangular collimation comparisons. Both had appreciable reductions ranging from 30% in the largest round collimation to 66% in the smallest round collimation (Figure 3A and C). However, given the close proximity to the imaging area these two locations are strongly dependent on the positioning of the primary X-ray beam and could vary considerably depending on the operator. Care was taken to document and visibly mark on the phantom the setup for each image in the full mouth series. The difference in significant vs insignificant findings in the salivary gland dose reduction between intraoral X-ray units could be partly due to the imaging on the two systems being completed on different dates. On each intraoral unit, the same two operators completed both the round and rectangular collimated image sets, so any operator variability between measurements on the same unit could be minimized.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate and analyze functional differences between 21.2, 25.7 and 31.7 cm2 round collimators with and without a universal operator installed rectangular collimator. It has previously been established in 2011 by Goren and colleagues that the use of rectangular collimators reduces radiation exposure at the periphery by 75% as well as reducing skin surface exposures by approximately 3.2 times compared to the round collimators.14 Ludlow and colleagues in 2008 studied radiation doses within an adult phantom head varying the different kind of collimation from round to rectangular as well as film types to assess the newly revised 2007 ICRP recommendations.15 Here, when studying FMX using F-Speed film with round cone and rectangular collimation increases in effective dose were noted for both based on the 2007 ICRP recommended increase in tissue weighting factors in this region. However, the rectangular collimation was noted as having an effective dose 80% less than the effective dose results for the round collimation using both the 1990 and 2007 recommended tissue weighting factors. Similarly, Kircos and colleagues in 1987 studied the differences in radiation dose from round versus rectangular collimation in E-speed film and found that organs outside the diagnostic imaging area had radiation scatter doses reduced by as much as an order of magnitude with rectangular collimators.16

At the highest kVp setting of 70, changing from 31.7 cm2 round to rectangular collimation resulted in a 59% KAP reduction. Similarly, with a setting of 240 ms, the change from round to rectangular on the 25.7 cm2 collimation resulted in a KAP reduction of 54%. This trend held true for the smallest round collimator as well. The reduction of the geometric area of the primary beam can be used as a guide for the expected amount of relative KAP reduction. In other words, our study showed that for a 62% reduction in beam area the KAP reduced by 59%, for a 53% reduction in area the KAP reduced by 54%, and for a 43% reduction in area the KAP dropped 40%. In conclusion, the change from the three sizes of round collimation to rectangular collimation resulted in a significant KAP reduction and are independent of manufacturer and X-ray technique when the technique remains unchanged as the collimation is increased. These results illustrate the importance of setting a gold-standard in radiological imaging for patients in both the academic setting and private practice. In 2002, a survey by Geist and Katz from University of Detroit Mercy, School of Dentistry and University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry illustrated how a large majority of USA dental schools are still using round collimators17

Radiation scatter dose to various peripheral organs were also studied using the three varying sized collimators and rectangular beam limiter. Results indicate significant decreases in dose received by locations containing organs such as the eyes and thyroid when the rectangular beam limiter was applied to the X-ray tube head. The results of this second study further emphasize why rectangular collimation is essential and how beneficial it can be in terms of radiation dosage reduction for the patient. Our results complement a study by Underhill et al in 1988 that focused on absorbed dose in the head and neck area, also by means of a phantom (tissue-equivalent) head.18 While scatter radiation itself is not widely studied in this application, we have demonstrated here that scatter can be reduced to different parts of the head and neck region based upon the collimation size and shape.

Comparisons with these three different sized collimators have never been studied in a single study before including their effect on radiation exposure to various head and neck organs. More studies to quantify scatter radiation dose to sensitive organs could be helpful in convincing professionals, or regulators in places where rectangular collimation is not a rigid requirement, of the potential benefit of sparing extra radiation dose to these organs over the course of a patient’s lifetime. As shown, the individual absorbed doses per mAs are in the µGy range. The clinical tube current–time product varies by manufacturer and imaging region (bitewing, periapical etc.) and it is difficult to find dosimeters that are sensitive enough to detect scatter radiation dose with typical clinical imaging techniques (kVp, mAs), so it is likely that quantifiable doses will be specific to the intraoral system studied and be relative to a scalable quantity such as the mAs.

Conclusions

Although rectangular collimation is the recommended collimation, round collimators of different sizes are still in use in oral and maxillofacial radiology practice settings in the USA. This is clearly against the principles advocated by ICRP.11 In Europe and many other countries, the rectangular collimation is obligatory and round collimators are disallowed by the regulatory agencies. This study looked at the differences between 21.2, 25.7 and 31.7 cm2 round collimators with and without rectangular primary beam limiting devices. It was observed that the reduction in KAP from the round to the rectangular collimation is on par with the geometric area reduction of the primary beam. The largest geometric area reduction of 62% yielded a radiation dose reduction of up to 60% at 60 kVp and 59% at 70 kVp. The <1% differences seen in variation of the X-ray tube voltage and tube current–time product suggest the geometry is a robust indicator of dose reduction for the primary beam and associated patient radiation dose reduction for tissues within the primary beam. The diameters of round collimators used in dentistry range from 5.1 to 7.0 cm. In the USA, FDA regulations still allow a maximum beam size of 7.0 cm on the patient skin using intraoral X-ray machines. Both the radiation dose reduction in primary beam KAP as a factor of geometric reduction and patient organ doses in relation to scatter radiation were significant in our experiment. This suggests that the use of rectangular collimators provide clinically relevant dose reduction for patients.

Footnotes

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank the Departments of Oral Medicine and Endodontics at the University Of Pennsylvania School Of Dental Medicine for providing us with the facilities to conduct this study.

Contributor Information

Dennise Magill, Email: magilld@ehrs.upenn.edu.

Nhan James Huu Ngo, Email: nhanngo@upenn.edu.

Marc A Felice, Email: mfelice@ehrs.upenn.edu.

Mel Mupparapu, Email: mmd@upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. US Food and Drug Administration Performance standards for Ionizing radiation emitting products, 21 CFR 1020 (US. Government Printing Office, Washington). 2018. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=1020 [Updated 2017/08/14. Cited 2018, May 1].

- 2. The American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs, Food and Drug Administration Dental Radiographic Examinations: Recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington). 2018. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/x-rays [Updated 2018/03/07. Cited 2018 May 2].

- 3. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement NCRP Report 145: Radiation Protection in Dentistry. Bethesda. Bethesda, MD: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2003. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gibbs SJ, Pujol A, Chen TS, Malcolm AW, James AE. Patient risk from interproximal radiography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984; 58: 347–54. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Committee on the biological effects of ionizing radiations, Board of radiation effects research, Commission on life sciences, National Research Council Health effects of exposure to low levels of Ionizing radiation : BEIR V. Washington: The British Institute of Radiology.; 1996. pp 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoogeveen RC, Hazenoot B, Sanderink GC, Berkhout WE. The value of thyroid shielding in intraoral radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2016; 45: 20150407. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20150407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White SC, Mallya SM. Update on the biological effects of ionizing radiation, relative dose factors and radiation hygiene. Aust Dent J 2012; 57(): 2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crane GD, Abbott PV. Radiation shielding in dentistry: an update. Aust Dent J 2016; 61: 277–81. doi: 10.1111/adj.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement org National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement. NCRP Report 159: Risk to the Thyroid from Ionizing Radiation. Bethesda, MD: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2008. 1–544. Ncrponline.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Research Council Health effects of exposure to low levels of Ionizing radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2. Washington, DC: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2006. 1–422. [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Commission on Radiological Protection Valentin J, The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. 103: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2007. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Authors on behalf of ICRP, Stewart FA, Akleyev AV, Hauer-Jensen M, Hendry JH, Kleiman NJ, et al. ICRP publication 118: ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs--threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann ICRP 2012; 41(1-2): 1–322. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dauer LT, Ainsbury EA, Dynlacht J, Hoel D, Klein BEK, Mayer D, et al. Guidance on radiation dose limits for the lens of the eye: overview of the recommendations in NCRP Commentary No. 26. Int J Radiat Biol 2017; 93: 1015–23. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2017.1304669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goren AD, Bonvento MJ, Fernandez TJ, Abramovitch K, Zhang W, Roe N, et al. Evaluation of radiation exposure with Tru-Align intraoral rectangular collimation system using OSL dosimeters. N Y State Dent J 2011; 77: 24–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, White SC. Patient risk related to common dental radiographic examinations. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 1237–43. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kircos LT, Angin LL, Lorton L. Order of magnitude dose reduction in intraoral radiography. J Am Dent Assoc 1987; 114: 344–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1987.0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geist JR, Katz JO. Radiation dose-reduction techniques in North American dental schools. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 93: 496–505. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Underhill TE, Chilvarquer I, Kimura K, Langlais RP, McDavid WD, Preece JW, et al. Radiobiologic risk estimation from dental radiology. Part I. Absorbed doses to critical organs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988; 66: 111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]