Abstract

Background

Patient education materials (pems) are frequently used to help patients make cancer screening decisions. However, because pems are typically developed by experts, they might inadequately address patient barriers to screening. We co-created, with patients, a prostate cancer (pca) screening pem, and we compared how the co-created pem and a pem developed by experts affected decisional conflict and screening intention in patients.

Methods

We identified and used patient barriers to pca screening to co-create a pca screening pem with patients, clinicians, and researchers. We then conducted a parallel-group randomized controlled trial with men 40 years of age and older in Ontario to compare decisional conflict and intention about pca screening after those men had viewed the co-created pem (intervention) or an expert-created pem (control). Participants were randomized using dynamic block randomization, and the study team was blinded to the allocation.

Results

Of 287 participants randomized to exposure to the co-created pem, 230 were analyzed, and of 287 randomized to exposure to the expert-created pem, 223 were analyzed. After pem exposure, intervention and control participants did not differ significantly in Decisional Conflict Scale scores [mean difference: 0.37 ± 1.23; 95% confidence interval (ci): −2.05 to 2.79]; in sure (Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk–benefit ratio, or Encouragement) scores (odds ratio: 0.75; 95% ci: 0.52 to 1.08); or in screening intention (mean difference: 0.09 ± 0.08; 95% ci: −0.06 to 0.24]).

Conclusions

The effectiveness of the co-created pem did not differ from that of the pem developed by experts. Thus, pem developers should choose the method that best fits their goals and resources.

Keywords: Patient engagement, co-creation, patient education materials, patient education, pca screening

BACKGROUND

Many cancer screening guidelines highlight evidence-based shared decision-making involving patients and clinicians1,2. Shared decision-making can involve the use of decision aids and other knowledge products such as printed patient education materials (pems)3,4. Because pems are inexpensive to develop and disseminate, they are one of the most common resources used by guideline developers and clinicians to disseminate cancer screening guideline recommendations to patients5. However, although patients are regularly engaged in developing decision aids6–8, pems are typically developed by experts (for example, clinicians and researchers) with minimal patient input9,10. As a result, pems might not optimally address underlying patient barriers and facilitators to cancer screening.

Involving patients in pem development might generate pems that are more effective and that address key patient barriers to the uptake of cancer screening recommendations11,12. For example, pems that are co-created with patients using established participatory design methods might enhance a patient’s understanding about the harms and benefits of prostate cancer (pca) screening13–15. By facilitating collaboration14, structured participatory design activities could help clinicians, researchers, and patients co-create pems that meet patient needs.

Co-creation with patients extends patient engagement in guideline development to the creation of guideline dissemination tools16–18. Because co-creation might require more time and resources than traditional approaches (for example, experts developing pems with minimal patient involvement)15,19, determining whether co-creation with patients adds value is important. Although researchers have previously co-created pems with patients, they have not compared the effectiveness of the co-created pems and the pems developed by experts20–23. We therefore compared a pca screening pem that was co-created by patients and one that was developed by experts for their effectiveness with respect to patient decisional conflict and intention to be screened (primary outcomes). We also compared the two pems with respect to pca screening knowledge and screening preferences, pem usability, and pem preferences on the part of patients (secondary outcomes).

METHODS

The study was conducted in 3 phases. In phase 1, we used established behaviour change frameworks and theories to systematically identify patient barriers to pca screening24,25. In phase 2, based on the barriers identified in phase 1, we co-created a pem with patients, researchers, and clinicians. In phase 3, we compared the effectiveness of the co-created pem and a pem developed by experts. The study was conducted with the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (“the Task Force”), which creates national guidelines for screening and prevention targeted to primary care physicians26. Patient engagement was guided by the patient engagement framework set out by Deverka et al.27, and patients were engaged in all phases.

Phase 1: Qualitative Interviews

This report of phase 1 is consistent with the coreq (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) guidelines28.

Recruitment

Eligible participants were English-speaking men 40 years of age and older living in Ontario who were targets for the Task Force guidelines about pca screening (men at average risk of pca). Participants were ineligible to participate if they were experiencing symptoms of pca, had been diagnosed with pca, worked in health care, or had conflicts of interest related to pca.

We recruited participants by posting recruitment ads on Kijiji (https://www.kijiji.ca/) and Craigslist (https://geo.craigslist.org/iso/ca/on) and by sending ads by e-mail to individuals who had participated in our previous research projects. After participants responded to the recruitment ad, they received a link to a screening survey designed to assess the eligibility criteria already described. Participants who completed the screening survey and who met inclusion criteria were eligible to participate. Participants were remunerated for their participation based on our institutional guidelines.

Procedure

Participants received an e-mail message with a link to a video about the Task Force pca screening recommendations29, an information sheet about pca screening (Appendix a), and the Task Force pca screening recommendations1. Approximately 1 week after receiving the e-mail message, participants completed a 60-minute, one-on-one telephone interview to assess patient barriers and facilitators to following the Task Force pca screening recommendations. They were told that the purpose of the interview was to discuss the Task Force recommendations. A female research assistant trained in conducting qualitative interviews facilitated the interviews using a semi-structured guide (Appendix b), which was informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (tdf), a meta-framework of 14 behaviour change constructs24,30. No other individuals were present during the interviews. The interviewer was involved in Task Force knowledge translation activities and was familiar with the pca screening guideline. She was not known to the participants before the study. Informed consent was obtained verbally. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and the interviewer made field notes. Participants did not take part in repeat interviews or review their transcripts.

Outcomes and Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were coded in NVivo (version 11: QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) independently by two research assistants using a double-coded thematic analysis approach31. First, one research assistant reviewed two transcripts to identify themes and develop a thematic framework and coding tree that was built around the barriers and facilitators to following the screening recommendations (regardless of tdf domain). Next, both research assistants used the framework to code 20% of the transcripts. Interrater reliability was calculated, and discrepancies (Kappa coefficients < 0.60) were resolved through discussion between the two research assistants. Conceptual changes were made to the coding framework as needed. For example, as more data became available, additional codes were created to accurately capture emerging themes. One research assistant used the updated framework to code the remaining transcripts. That research assistant then reviewed the codes and developed a list of patient barriers and facilitators to following the Task Force’s pca screening recommendations.

To understand the underlying reasons why patients might or might not follow the Task Force’s pca screening recommendations, the patient barriers and facilitators were mapped to the tdf24. To identify behaviour change mechanisms associated with the barriers and facilitators, the barriers and facilitators were mapped to the Capabilities, Opportunities, and Motivation Behaviour-Based Theory of Change25. Participants did not receive the coding or mapping results.

Sample Size

We aimed to recruit 10 participants. To achieve saturation of themes, 6–12 participants are recommended for one-on-one interviews32.

Phase 2: PEM Co-creation

This report of phase 2 is consistent with the coreq guidelines28.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using the same procedure and eligibility criteria used in phase 1.

Procedure

Participants received the same background materials used in phase 1 and a written consent form. They then completed in-person meeting activities and pem prototype review tasks (described in the subsections that follow) that were based on established participatory design methods14,15,33,34. The activities were not audio- or video-recorded, and the meeting facilitators did not take field notes.

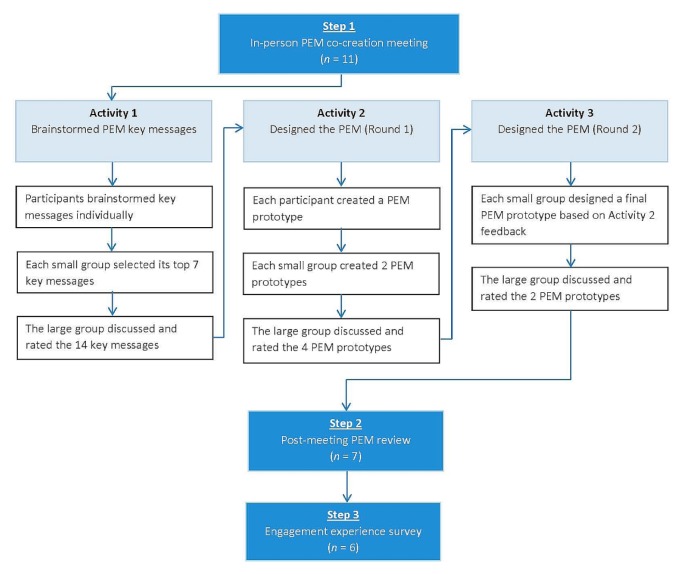

In-Person Co-creation Meeting

Approximately 1 week after receiving the background materials, participants attended a 1-day, in-person pem co-creation meeting at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, with the chair of the Task Force’s Prostate Cancer Screening Working Group and the Task Force’s pem developer. The meeting was facilitated by 3 female research assistants (including NYB and DB) who were trained in conducting focus groups. All were involved in Task Force knowledge translation activities, familiar with the pca screening guideline, and not known to the participants before the study. To make small-group co-creation activities feasible, participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 small groups, each of which included either the Working Group chair or the pem developer. At meeting onset, participants received an overview of the project goals, the meeting purpose (to co-create a pem), the Task Force pca screening recommendations, factors that influence behaviour change, and the barriers and facilitators identified in phase 1. The next few subsections summarize the in-person meeting and follow-up activities. Appendix c and Figure 2 describe the complete methods.

FIGURE 2.

Study flow diagram.

Activity 1—Brainstorm PEM Key Messages

Following established participatory design methods14,15,33,34, participants used the nominal group technique to brainstorm key messages for the pem35. The nominal group technique is a structured group decision-making process in which participants independently generate ideas, share their ideas with the group, and then discuss and rate the ideas generated. In activity 1, participants generated key messages for inclusion in the pem to address the barriers and facilitators identified in phase 1. Through discussion, each small group identified their top 7 key messages, which were shared during a subsequent large-group discussion. Participants then used an interactive voting strategy to independently rate the 14 key messages on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 [not at all important (to include in the pem)] to 7 [very important (to include in the pem)]. The 7 key messages with the highest mean ratings were shared and discussed with the participants.

Activity 2—Design the PEM (Round 1)

Participants used the nominal group technique to design the pem35. They first used the top 7 key messages from activity 1 to independently design a pem prototype, which was shared with their small group. Each small group then created 2 prototypes, which were discussed by the large group. Using the same approach as in activity 1, participants rated each prototype on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly dislike) to 7 (strongly like). The mean ratings were shared and discussed with the participants.

Activity 3—Design the PEM (Round 2)

Small-group participants designed a final pem prototype either by modifying one of their activity 2 prototypes or by creating a new version. The large group then discussed the prototypes designed by each group and rated them on the scale used in activity 2. The mean ratings were shared and discussed with participants. Because of a technical error, data for Activity 3 were not recorded.

Post-Meeting PEM Prototype Review

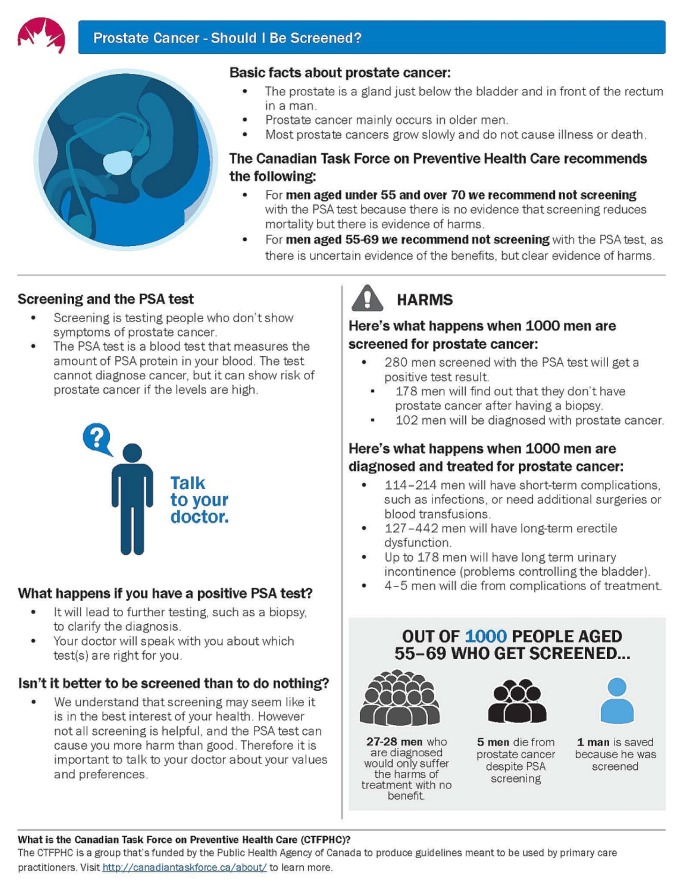

After the meeting, the pem developer created electronic versions of the two activity 3 pem prototypes. Participants used the online collaboration platform Conceptboard (Digital Republic Media Group, Halle, Germany) to provide feedback about each prototype. Specifically, they rated each prototype on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly dislike) to 7 (strongly like) and provided comments. The pem developer used the feedback to create a final version of the co-created pem (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phase 2 final co-created patient education material.

Engagement Experience Survey

The final co-created pem was shared with the participants, and they completed a 15-item online survey [Qualtrics, Provo, UT, U.S.A. (https://www.qualtrics.com)] about their engagement experience [Moore A. Personal communication]. Participants rated each item using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (no extent) to 7 (very large extent). Reminders were sent by e-mail at 7 and 14 days.

Outcomes and Data Analysis

We assessed attendee perceptions of the pem key messages and prototypes by calculating the mean and interquartile range for each key message and prototype rating during activities 1–3 and the post-meeting review. We conducted a content analysis of open-ended comments from the post-meeting review by the participants. We assessed the engagement experience of the participants by calculating the mean and interquartile range for each engagement experience item.

Sample Size

To facilitate participation in participatory design and co-creation research, participant sample sizes are small (for example, 4–16 participants)33,34,36. We aimed to recruit 8–10 participants.

Phase 3: PEM Evaluation

This report of phase 3 is consistent with the consort (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement and the consort extension for trials of nonpharmacologic interventions37,38.

Study Design

In October 2017, we conducted a parallel-group randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of two different pems: one co-created with patients, and another developed by experts. We registered the trial with http://ClinicalTrials.gov/(NCT03222466).

Study Population

Eligible participants were those who met the eligibility criteria used in phases 1 and 2. During a 3-week period from 6 October 2017 to 27 October 2017, we recruited participants through AskingCanadians, an online research community [Delvinia Technology Inc., Toronto, ON (http://www.askingcanadians.com)]. Members of that community who matched the demographics of our target population received an e-mail invitation from AskingCanadians requesting their participation in the study. Individuals who responded to the invitation were directed to a survey software platform developed by St. Michael’s Hospital where they were asked to complete the screening survey used in phases 1 and 2. Participants who completed the screening survey and who met eligibility criteria were given an informed consent document and directed to the main online survey, which was administered using the same survey software platform. Participants received reward points from either AskingCanadians or one of several retailers.

Intervention

Co-created PEM

Participants allocated to the intervention group viewed an electronic version of the pem that was co-created in phase 2. They viewed the pem in the online survey after completing a series of baseline measures (described in a later subsection). Participants were permitted to view the pem for as long as they wished before continuing with the survey.

Expert-Created PEM

Participants allocated to the control group viewed an electronic version of a pca screening pem that had been created by experts in 2014 for the Task Force39. Briefly, clinicians and the guideline working group identified key messages. The same pem developer who developed the co-created pem then created a prototype, which underwent usability testing by patients and clinicians using established methods9. Participants viewed the existing pem in the online survey after completing a series of measures (described in a later subsection); they were permitted to view it for as long as they wished.

Randomization

When a participant entered the main survey, computerized block randomization (48 blocks with a block size of 12) was used to randomly assign that participant to either the intervention or control group, with allocation concealment. Participants were then automatically directed to the version of the main survey that corresponded to their group assignment. The study team and research assistants were blinded to treatment allocation.

Outcomes

At the main online survey, participants completed these outcome measures:

-

■ Primary outcomes

▪ Decisional conflict Decisional conflict with respect to pca screening was assessed using the 16-item valid and reliable Decisional Conf lict Scale (dcs) and the 4-item valid and reliable sure (Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk–benefit ratio, Encouragement) screening test for decisional conflict before and after the participant had viewed the assigned pem40,41. The dcs ratings are analyzed by summing the responses to the 16 items, dividing the sum by 16, and multiplying the result by 25 to create a continuous score ranging from 0 to 100. The higher the score, the greater the decisional conflict. Scores greater than 37.5 are associated with decisional delay and uncertainty40. In the sure test, participants receive a score of 1 if they respond “yes” (which indicates certainty) to all 4 items. They receive a score of 0 if they respond “no” to any item41.

▪ Intention to be screened Intention to be screened for pca was assessed before and after the participant viewed the assigned pem. Participants rated their agreement with the statement “I plan to get screened for pca within the next 12 months” on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher ratings on the intention scale indicate greater self-reported intention to be screened.

-

■ Secondary outcomes

▪ Knowledge Knowledge of pca screening was assessed before and after the participant had viewed the assigned pem. The 7 true-or-false questions that were posed had been developed by the Task Force Prostate Cancer Screening Working Group and the project steering committee (Table I).

▪ Screening preference Preference related to pca screening was assessed before and after the participant had viewed the assigned pem. This multiple-choice question asked whether participants preferred to be screened for pca, preferred not to be screened, or were unsure of their preference.

▪ PEM usability Usability of the pem was assessed using the 10-item valid and reliable System Usability Scale (sus)42. Participants completed the scale after they had completed the post-test measures of the outcomes already described. Following the sus manual, we converted participant responses to a 0-to-100 sus score; higher scores indicate higher usability42.

▪ PEM preference The pem preferred by the participant was identified by showing both pems in a randomized order at study end and by asking the participant to select the preferred version. Participants completed this task after rating the assigned pem’s usability.

TABLE I.

Prostate cancer screening knowledge

| Please indicate whether each question below is true or false. | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Most men will die from something other than prostate cancer. | True |

| 2. | Screening for prostate cancer involves testing men who do not show symptoms for prostate cancer. | True |

| 3. | Having a normal prostate cancer screening test result means it is certain that there is no prostate cancer present. | False |

| 4. | Medical experts in Canada agree that all men aged 55 years or older should have prostate cancer screening with the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. | False |

| 5. | Treatment for prostate cancer can cause undesirable short- and long-term problems for some men. These problems may include additional surgeries, erectile dysfunction, and urinary incontinence. | True |

| 6. | Screening for prostate cancer can cause both benefits and harms. | True |

| 7. | A prostate cancer screening test will diagnose prostate cancer. | False |

Sample Size

A sample size calculation revealed that we would need 352 participants (176 in each group) to detect a 0.3 difference between the groups in one of the primary outcomes (decisional conflict according to the dcs) with 80% power at a 0.05 level of significance. Assuming 20% attrition, the total number of participants required was 422.

Data Analysis

Decisional Conflict

We used analysis of covariance, controlling for pre-test dcs scores, to analyze between-group differences in post-test dcs scores. We used a repeated-measures analysis of variance with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction to assess within-group differences in pre-test to post-test scores.

Between groups, we used chi-square tests to assess post-test differences for each sure item and the overall sure score. Within groups, we used a McNemar test to assess pre-test to post-test differences for each sure item and the overall sure score.

Intention to Be Screened

Between groups, we used analysis of covariance, controlling for pre-test screening intention, to assess post-test differences in screening intention. Within each group, we used a repeated-measures analysis of variance to assess pre-test to post-test differences in screening intention.

Knowledge

We coded knowledge test items as “correct” or “incorrect.” Between groups, we used chi-square tests to assess differences in post-test responses for each knowledge question and in the combined knowledge score. Within groups, we used a McNemar test to assess pre-test to post-test differences in correct responses to each question. We used chi-square tests to assess pre-test to post-test differences in the total number of questions that participants answered correctly.

Screening Preference

Between the pem groups, we used a chi-square test to assess post-test differences in screening preferences. Within each pem group, we used symmetry and marginal homogeneity tests to assess pre-test to posttest differences.

PEM Usability

We used a one-way analysis of variance to assess the difference in the scores for the two pems.

PEM Preference

We computed frequencies for participants who chose the co-created pem compared with the existing pem as their preferred material. We used a chi-square test to assess differences in preferences between the two pem groups.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Qualitative Interviews

Of 29 people who responded to the recruitment announcement, 10 completed the screening survey and were eligible to participate; the remaining 19 either did not complete the screening survey or were ineligible to participate. Most participants were 40–69 years of age (80%, n = 8). Table II summarizes the participant demographic information.

TABLE II.

Demographic characteristics of the participants, by phase

| Characteristic | Phase [n (%)] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Participants | 10 | 9 | 453 |

|

| |||

| Age group | |||

| 40–54 Years | 4 (40) | 5 (56) | 132 (29) |

| 55–69 Years | 4 (40) | 3 (33) | 268 (59) |

| ≥70 Years | 2 (20) | 1 (11) | 53 (12) |

|

| |||

| Setting | |||

| Rural | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 115 (25) |

| Suburban | 2 (20) | 2 (22) | 137 (30) |

| Urban | 8 (80) | 4 (44) | 201 (44) |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 3 (33) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Educationa | |||

| Less than high school | — | — | 4 (1) |

| High school | — | — | 95 (21) |

| College diploma or bachelor’s degree | — | — | 250 (55) |

| Graduate or professional degree | — | — | 104 (23) |

Collected only in phase 3.

We identified 62 barriers and facilitators to following the pca screening recommendations. Those barriers and facilitators mapped to 12 tdf domains and 5 components of the Capabilities, Opportunities, and Motivation Behaviour-Based Theory of Change (Appendix d).

Phase 2: PEM Co-creation

Of the 27 people who responded to the recruitment announcement, 9 completed the screening survey and were eligible to participate; the remaining 18 either did not complete the screening survey or were ineligible. All 9 patient participants completed the in-person meeting activities, 7 completed the post-meeting pem prototype review on Conceptboard, and 6 completed the engagement experience survey. Most participants were 40–54 years of age (56%, n = 5). Table II summarizes the demographic information for this group.

In-Person Co-creation Meeting and Post-Meeting Review

Based on their ratings, meeting attendees indicated that it was most important to include information about pca screening facts and the Task Force pca screening recommendations in the pem. Tables III and IV show the participant ratings of the pem key messages and prototypes in activities 1–2 and the post-meeting review ratings. Table V summarizes the comments about the post-meeting review prototype. Table VI outlines the key differences between the two pems.

TABLE III.

Ratings of the patient education material key messages from 10 participants

| Key message | Mean | IQRa |

|---|---|---|

| Basic facts about prostate cancer | 6.80 | 7.00–7.00 |

| Task Force recommendations on PSA screening | 6.70 | 6.25–7.00 |

| Harms of screening (including statistics) and specific harms | 6.10 | 6.00–7.00 |

| “Evidence on the PSA test has changed” | 5.80 | 5.00–7.00 |

| Address fear (“Would rather know”) and trust in accuracy of test | 5.80 | 5.00–7.00 |

| Explain screening | 5.70 | 6.00–7.00 |

| What happens if the PSA test result is positive? | 5.70 | 5.25–7.00 |

| Benefits of screening (including statistics) | 5.60 | 4.50–7.00 |

| Trust in organization that provides information (for example, “Task Force is independent”) | 5.50 | 5.00–6.00 |

| Trust in anecdotal evidence (for example, “I got screened and got harmed”) | 5.40 | 5.00–6.75 |

Expressed as first–third quartile. Values include ratings made by the Task Force Prostate Cancer Screening Working Group chair.

IQR = interquartile range; Task Force = Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

TABLE IV.

Ratings of the patient education material prototypes presented during phase 2, activity 2, and the post-meeting review

| Prototype | Rating | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean | IQRa | |

| Activity 2 (n=11) | ||

| Prototype 2A | 5.55 | 6.00–6.00 |

| Prototype 2B | 4.91 | 4.50–5.50 |

| Prototype 2C | 5.45 | 5.00–6.00 |

| Prototype 2D | 5.09 | 4.50–6.00 |

|

| ||

| Post-meeting review (n=7) (Conceptboardb) | ||

| Follow-up prototype A | 5.50 | 5.00–6.50 |

| Follow-up prototype B | 5.79 | 5.50–6.75 |

Interquartile range expressed as first–third quartile. Activity 2 values include ratings given by the Task Force Prostate Cancer Screening Working Group chair and PEM developer.

Digital Republic Media Group, Halle, Germany.

TABLE V.

Comments from the phase 2 post-meeting review of the patient education material

| Comments | Follow-up prototype A | Follow-up prototype B |

|---|---|---|

| Positive |

|

|

| Negative |

|

|

| Suggestions |

|

|

Task Force = Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.

TABLE VI.

Key differences between the co-created patient education material (PEM) and the existing PEM

| Co-created PEM | Existing PEM |

|---|---|

| ▪ Starts with basic facts about prostate cancer | ▪ Starts with recommendations from the CTFPHC |

| ▪ Removed the 1000-person diagram to include three key messages | ▪ Includes a 1000-person diagram with seven key messages |

| ▪ Objective is to answer commonly asked questions | ▪ Objective is to provide recommendations from the CTFPHC |

| ▪ Includes an introduction to the CTFPHC | ▪ Does not include an introduction to the CTFPHC |

| ▪ Greater emphasis on the harms of prostate screening and importance of talking to a doctor | ▪ Includes the harms and does not state the importance of talking to a doctor |

CTFPHC = Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.

Engagement Experience Survey

Ratings by the participants revealed that they had a positive engagement experience (means ≥ 5.17 on a 7-point scale, Table VII).

TABLE VII.

Ratings given to the phase 2 engagement experience survey by 6 respondents

| Item | Mean | IQRa |

|---|---|---|

| To what extent do you believe that your ideas were heard during the engagement process? | 6.00 | 6.00–6.00 |

| To what extent did you feel comfortable contributing your ideas to the engagement process? | 5.67 | 5.25–6.00 |

| Did organizers take your contributions to the engagement process seriously? | 6.00 | 6.00–6.00 |

| To what extent do you believe that your input will influence final decisions that underlie the engagement process? | 5.50 | 5.25–6.00 |

| To what extent do you believe that your values and preferences will be included in the final health advice from this process? | 5.17 | 5.00–5.75 |

| To what extent were you able to clearly express your viewpoints? | 5.83 | 5.00–6.75 |

| How neutral in their opinions (regarding topics) were the organizers during the engagement process? | 5.50 | 5.00–6.00 |

| Did all participants have equal opportunity to participate in discussions? | 6.17 | 6.00–6.75 |

| How clearly did you understand your role in the process? | 6.00 | 6.00–6.00 |

| To what extent was information made available to you either prior to or during the engagement process so as to participate knowledgeably in the process? | 5.33 | 5.00–5.75 |

| To what extent were the ideas contained in the information material easy to understand? | 5.50 | 5.00–5.75 |

| How clearly did you understand what was expected of you during the engagement process? | 6.00 | 6.00–6.00 |

| How clearly did you understand what the goals of the engagement process were? | 6.17 | 6.00–6.00 |

| To what extent would you follow health advice from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (if it related to your health condition)? | 6.50 | 6.00–7.00 |

| To what extent would you advise others to follow health advice from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (if it related to their health condition)? | 6.00 | 6.00–6.00 |

Interquartile range expressed as first–third quartile.

Phase 3: PEM Evaluation

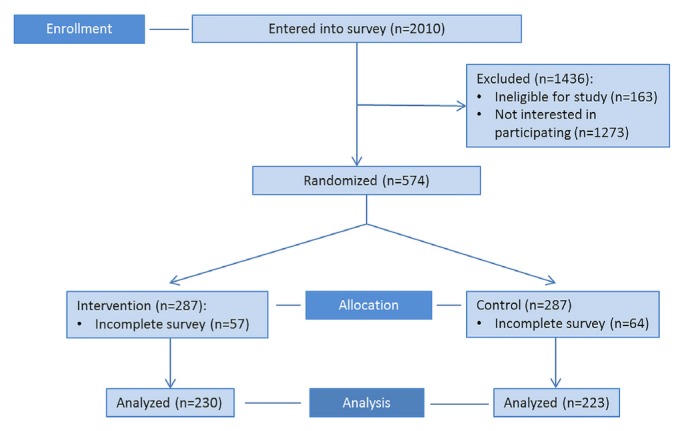

Between 6 October 2017 and 27 October 2017, 2010 people were sent an invitation to participate. Of those 2010 people, 574 completed the screening survey and were eligible for randomization; the remaining 1436 people either did not complete the screening survey or were ineligible to participate. Of the 574 eligible participants, 287 were randomized to the intervention group [230 (80%) completed the study and were analyzed] and 287, to the control group [223 (78%) completed the study and were analyzed, Figure 3]. Most participants were 55–69 years of age (59%, n = 268) and had a college or bachelor’s degree or higher (78%, n = 354). Table II summarizes demographic information for the participants.

FIGURE 3.

Phase 3 CONSORT flow diagram. PEM = patient education material.

Decisional Conflict

The mean difference in the post-test dcs score between the intervention and control groups was not statistically significant [mean difference: 0.37 ± 1.23; p = 0.76; 95% confidence interval (ci): −2.05 to 2.79]. No difference between the intervention and control groups in the total post-test sure scores was evident [odds ratio (or): 0.75; 95% ci: 0.52 to 1.08]. However, within each group, significant pre-test to post-test differences for both outcomes were observed (Tables VIII and IX).

TABLE VIII.

Phase 3 Decisional Conflict Scale scores from 453 participants

| Test group | Pre-test mean | Post-test mean | Within-group difference | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| F | df | p Value | ||||

| Intervention (n=230) | 60.92±18.88 | 65.94±18.58 | 30.28 | 1,229 | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Control (n=223) | 58.55±20.01 | 63.95±18.66 | 28.83 | 1,222 | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Between-group difference [posttest scores (n=453)] | 0.09 | 1,450 | 0.76 | −2.05 to 2.79 | ||

CI = confidence interval.

TABLE IX.

Phase 3 SURE test scores from 453 participants

| Item | Question | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | |

| Intervention (n=230) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Pre-test proportions | |||||

| Sure | 0.6 | 0.43 | 0.5 | 0.65 | 0.39 |

| Unsure | 0.4 | 0.57 | 0.5 | 0.35 | 0.61 |

|

| |||||

| Post-test proportions | |||||

| Sure | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 0.56 |

| Unsure | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.3 | 0.44 |

|

| |||||

| Within-group differences | |||||

| McNemar p | 0.008 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 2.50 | 11.80 | 6.14 | 1.92 | 7.67 |

| 95% Confidence interval | 1.31 to 4.77 | 5.76 to 24.16 | 3.05 to 12.36 | 0.97 to 3.81 | 3.73 to 15.75 |

|

| |||||

| Control (n=223) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Pre-test proportions | |||||

| Sure | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.33 |

| Unsure | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.67 |

|

| |||||

| Post-test proportions | |||||

| Sure | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.49 |

| Unsure | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

|

| |||||

| Within-group differences | |||||

| McNemar p | 0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 1.60 | 16.67 | 7.50 | 3.29 | 5.50 |

| 95% CI | 0.92 to 2.78 | 7.09 to 39.16 | 3.64 to 15.46 | 1.48 to 7.30 | 2.82 to 10.74 |

|

| |||||

| Between-group differences in post-test scores (n=453) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Chi-square (df=1) | 2.94 | 2.61 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 2.36 |

|

| |||||

| p Value | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.12 |

|

| |||||

| Odds ratio | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.75 |

|

| |||||

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.49 to 1.05 | 0.50 to 1.07 | 0.62 to 1.34 | 0.62 to 1.37 | 0.52 to 1.08 |

SURE = Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk–benefit ratio, Encouragement.

Intention to Be Screened

The mean difference in post-test screening intention between the intervention and control groups was not statistically significant (mean difference: 0.09 ± 0.08; p = 0.24; 95% ci: −0.06 to 0.24). However, within each group, significant pre-test to post-test differences were observed (Table X).

TABLE X.

Phase 3 screening intention scores from 453 participants

| Test group | Pre-test mean | Post-test mean | Within-group difference | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| F | df | p Value | ||||

| Intervention (n=230) | 3.63±1.14 | 3.36±1.22 | 19.60 | 1,229 | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Control (n=223) | 3.44±1.08 | 3.31±1.13 | 6.59 | 1,222 | 0.01 | |

|

| ||||||

| Between-group difference [post-test scores (n=453)] | 1.36 | 1,450 | 0.24 | −0.06 to 0.24 | ||

CI = confidence interval.

Knowledge

No significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the post-test total knowledge scores was evident (or: 1.10; 95% ci: 0.94 to 1.29). However, within each group, significant pre-test to post-test differences were observed (Table XI).

TABLE XI.

Phase 3 knowledge scores from 453 participants

| Item | Question | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total | |

| Intervention (n=230) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pre-test proportions | ||||||||

| Correct | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.9 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| Incorrect | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.1 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.37 |

|

| ||||||||

| Post-test proportions | ||||||||

| Correct | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.6 | 0.75 |

| Incorrect | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.4 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||

| Within-group differences | ||||||||

| McNemar or chi-square p value | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 1.40 | 1.80 | 1.67 | 10.17 | 1.50 | 12.71 | 3.06 | 1.77 |

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.62 to 3.14 | 0.84 to 3.86 | 0.82 to 3.38 | 5.17 to 20.00 | 0.68 to 3.32 | 7.01 to 23.06 | 1.79 to 5.23 | 1.52 to 2.06 |

|

| ||||||||

| Control (n=223) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pre-test proportions | ||||||||

| Correct | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.75 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Incorrect | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.37 |

|

| ||||||||

| Post-test proportions | ||||||||

| Correct | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.33 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 0.73 |

| Incorrect | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.27 |

|

| ||||||||

| Within-group difference | ||||||||

| McNemar or chi-square p value | 0.11 | 0.71 | 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Odds ratio | 2.13 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 24.50 | 1.85 | 10.25 | 1.82 | 1.61 |

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.94 to 4.83 | 0.59 to 2.56 | 0.58 to 2.15 | 9.45 to 63.51 | 0.95 to 3.59 | 5.71 to 18.39 | 1.02 to 3.27 | 1.38 to 1.87 |

|

| ||||||||

| Between-group difference [post-test scores (n=453)] | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Chi-square (df=1) | 0.75 | 0.15 | 1.73 | 0.42 | 1.16 | 0.16 | 1.77 | 1.43 |

| p Value | 0.39 | 0.7 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Odds ratio | 0.75 | 0.88 | 1.35 | 1.14 | 1.42 | 1.10 | 1.29 | 1.10 |

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.40 to 1.43 | 0.46 to 1.68 | 0.86 to 2.12 | 0.77 to 1.68 | 0.75 to 2.70 | 0.70 to 1.71 | 0.89 to 1.87 | 0.94 to 1.29 |

Screening Preference

After pem exposure, the intervention and control participants did not differ significantly in their pca screening preferences [chi-square (2) = 0.23; p = 0.89; or: 0.94; 95% ci: 0.74 to 1.20]. However, within each group, significant pre-test to post-test differences were observed (Table XII).

TABLE XII.

Phase 3 screening preferences from 453 participants

| Test group | Undergoing screening | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Yes | No | Unsure | |

| Intervention (n=230) | |||

| Pre-test proportion | 0.8 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Post-test proportion | 0.64 | 0.2 | 0.17 |

| Within-group difference | |||

| Symmetrya | 35.56, p<0.001 | ||

| Marginal homogeneityb | 35.18, p<0.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Control (n=223) | |||

| Pre-test proportion | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Post-test proportion | 0.62 | 0.2 | 0.18 |

| Within-group difference | |||

| Symmetrya | 34.57, p<0.001 | ||

| Marginal homogeneityb | 34.38, p<0.001 | ||

|

| |||

| Between-group difference [post-test scores (n=453)] | |||

| Χ2 (df=2) | 0.23 | ||

| p Value | 0.89 | ||

| Odds ratio | 0.94 | ||

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.74 to 1.20 | ||

Chi-square (df=3).

Chi-square (df=2).

PEM Usability

The mean difference in the sus score between the two pems was statistically significant, (mean difference: 3.38 ± 1.39; 95% ci: 0.66 to 6.11; d = 0.22). The mean sus rating for the co-created pem (63.27 ± 14.84) was statistically higher than that for the existing pem (59.89 ± 14.70, p = 0.02).

PEM Preference

Significantly more participants preferred the co-created pem (n = 231, 51%) to the existing pem [n = 222, 49%; chi-square (1) = 75.71; p < 0.001; Table XIII]. A moderate association between group (intervention vs. control) and pem preference was also evident, such that participants were less likely to prefer the pem that they had viewed earlier (Cramér V = 0.41; p = 0.001; or: 0.18; 95% ci: 0.12 to 0.26).

TABLE XIII.

Phase 3 patient education material (PEM) preferences from 453 participants

| Test group | Proportion | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Existing PEM | Co-created PEM | |

| Intervention (n=230) | 0.69 | 0.31 |

|

| ||

| Control (n=223) | 0.28 | 0.72 |

|

| ||

| Overall (n=453) | 0.49 | 0.51 |

|

| ||

| Between-group difference (n=453) | ||

| Chi-square (df=1) | 75.71 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | |

| Odds ratio | 0.18 | |

| 95% Confidence interval | 0.12 to 0.26 | |

DISCUSSION

Researchers, clinicians, and funders have increasingly emphasized the importance of engaging patients in guideline development and dissemination12,16–18. We compared the effectiveness of a pca screening pem that was co-created with patients and one that was developed by experts (namely content, communication, and design experts). Co-creation focused on the goal of having patients collaborate and be empowered in the research process43. Patient advice and recommendations were incorporated at each level, and some patients were involved as leaders and part of the research team to ensure that they had decision-making authority during concept development. Our findings showed that, although the co-created pem had a higher usability score and was preferred to the expert-created pem, no difference was evident in decisional conflict or screening intention after participants had viewed either the cocreated or the expert-created pem. Similarly, no differences in patient screening preferences or knowledge were observed. Those findings are likely the result of both pems producing similar changes in decisional conflict, knowledge, screening intention, and preferences with respect to pca screening that were consistent with evidence-based screening recommendations1,2. Thus, although cocreation might yield patient resources that have an effect on screening-related decisional conflict, intention, knowledge, and preferences, the effect might not be greater than the effect achieved by pems developed primarily by experts. Interestingly, both groups in the trial showed a preference for the pem that they had viewed last. Overall, when creating patient resources related to cancer screening, pem developers might want to choose the development method that best suits their goals and available resources.

Reflections on the Value of Funding

This project was funded by the Knowledge Translation Research Network. The study was also conducted with the support of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and Cancer Care Ontario through funding provided by the Government of Ontario. The Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and Cancer Care Ontario have a mandate for research dissemination and implementation to optimize cancer care delivery. Their funding allowed us to test an important question identified from the dissemination and implementation literature. The results will inform not just dissemination of the guideline in the present project, but also other cancer screening and prevention guidelines. Moreover, the connection with others who were funded through the Knowledge Translation Research Network allowed for sharing of experiences, furthering research impact. This funding mechanism is an excellent example of how the principles of integrated knowledge translation (specifically co-creation) can be implemented and tested efficiently in a research project.

Limitations

We note a few limitations of the present study. First, participants in phases 1–3 were all men 40 years of age and older who were highly educated and living in Canada. The co-creation process might have yielded different results if we had engaged patients from another demographic group, including those with lower health literacy or a different geographic location. Although the phase 1 and 2 sample sizes were typical of the number of patients engaged in qualitative research and participatory design initiatives33,34,36, they were relatively small. Thus, the barriers that the participants identified and the pem prototypes that they created might not reflect the needs of the broader pca screening population. Second, patients in phase 2 co-created the pem by completing a specific set of activities and did not receive extensive training in the pem content area. We based the co-creation activities on established participatory design methods33,34,36 and gave participants basic resources concerning the pem content area so that they could contribute from the perspective of a lay patient. We might have obtained different results if we had used a different co-creation method. Third, phase 2 participants might have withheld some of their ideas during the inperson meeting because the pem developer and the Task Force Prostate Cancer Screening Working Group Chair were present. However, in the engagement survey, participants indicated that they felt relatively comfortable contributing their ideas during the co-creation process. Fourth, we did not control for testing of multiple primary outcomes in phase 3. However, given the null between-group results, that lack of controls did not influence our conclusions. Fifth, because we did not conduct a cost analysis of the resources required to produce each pem, we cannot draw conclusions about the potential economic impact of the two pem development methods. The relative resource implications of the two methods should be examined in future.

Future studies testing co-creation of pems should focus on engaging patients with varying health literacy levels. Moreover, the present study focused on men, given that they were the target for the pca screening guideline. Future research could include other relevant populations, including women and children. It will also be critical to include economic analyses of the development of these tools.

CONCLUSIONS

We compared the effectiveness of pems about pca screening— one being co-created by patients and one having been developed by experts—with respect to decisional conflict and intention to be screened on the part of patients. Both pems affected decisional conflict and changed screening intention and preferences to be more aligned with screening recommendations. Both also increased knowledge about some screening facts. The effects of the co-created pem and the pem developed primarily by experts were similar. When developing patient resources about cancer screening, researchers and health care organizations might want to choose the pem development method that best fits with their goals and resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mahrukh Zahid for assistance with data collection, David Flaherty for assistance with pem development and graphic design, and Dr. Jamie Park for assistance with revising the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Rachel Rodin for helpful suggestions throughout the project. This research was funded by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research. BDT is supported by a Fonds de Recherche Québec–Santé researcher award. SES is funded by a tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation and the Mary Trimmer Chair in Geriatric Medicine.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare the following interests: The Knowledge Translation Program at St. Michael’s Hospital receives funding from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell N, Connor Gorber S, Shane A, et al. Recommendations on screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test. CMAJ. 2014;186:1225–34. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Preventive Services Task Force (uspstf) Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Rockville, MD: uspstf; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1213–21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2572–80. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1380-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor A, Stacey D, Boland L. Ottawa Decision Support Tutorial. Ottawa, ON: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2015. [Available online at: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odst/pdfs/odst.pdf; cited 30 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trikalinos TA, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Zgodic A, Ntzani EE. Decision Aids for Cancer Screening and Treatment. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. (Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 145. ahrq Publication No. 15-EHC002-EF). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (ctfphc) Procedure Manual. Toronto, ON: ctfphc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Kingdom, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (nice) The Guidelines Manual. London, UK: nice; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barratt A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences into health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:239–51. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00343-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schipper K, Bakker M, De Wit M, Ket JC, Abma TA. Strategies for disseminating recommendations or guidelines to patients: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:82. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0447-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somerville MM, Howard Z. A comparative study of two design charrettes: implications for codesign and participatory action research. CoDesign. 2014;10:46–62. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2014.881883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spinuzzi C. The methodology of participatory design. Tech Commun. 2005;52:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Díaz Del Campo P, Gracia J, Blasco JA, Andradas E. A strategy for patient involvement in clinical practice guidelines: methodological approaches. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:779–84. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.049031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. on behalf of the US Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.agree Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the agree project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badiu C, Bonomi M, Borshchevsky I, et al. on behalf of cost Action BM1105. Developing and evaluating rare disease educational materials co-created by expert clinicians and patients: the paradigm of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:57. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith F, Wallengren C, Öhlén J. Participatory design in education materials in a health care context. Action Res (Lond) 2017;15:310–36. doi: 10.1177/1476750316646832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jewitt N, Hope AJ, Milne R, et al. Development and evaluation of patient education materials for elderly lung cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:70–4. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wieland ML, Nelson J, Palmer T, et al. Evaluation of a tuberculosis education video among immigrants and refugees at an adult education center: a community-based participatory approach. J Health Commun. 2013;18:343–53. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.727952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. Surrey, UK: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birtwhistle R, Pottie K, Shaw E, et al. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care: we’re back! Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:13–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deverka PA, Bangs R, Kreizenbeck K, et al. A new framework for patient engagement in cancer clinical trials cooperative group studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:553–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (coreq): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (ctfphc) Prostate Cancer: Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening Video [Web resource] Toronto, ON: ctfphc; 2014. [Available at: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/tools-resources/videos#prostatecancerscreening; cited 27 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawton R, Heyhoe J, Louch G, et al. on behalf of the aspire Programme. Using the Theoretical Domains Framework (tdf) to understand adherence to multiple evidence-based indicators in primary care: a qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2016;11:113. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London, UK: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakobyan L, Lumsden J, O’Sullivan D. Older adults with amd as co-designers of an assistive mobile application. Int J Mobile Hum Comput Interact. 2014;6:54–70. doi: 10.4018/ijmhci.2014010104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehouse SR, Lam PY, Balka E, et al. Co-creation with TickiT: designing and evaluating a clinical eHealth platform for youth. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2:e42. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delbecq AL, van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis RD, Kurnlawan SH. Increasing the usability of online information for older users: a case study in participatory design. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2000;12:263–76. doi: 10.1207/S15327590IJHC1202_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D on behalf of the consort group. consort 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P on behalf of the consort npt group. consort statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a consort extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:40–7. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (ctfphc) Prostate cancer—1000-person tool [Web page] Toronto, ON: ctfphc; 2014. [Available at: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/tools-resources/prostate-cancer-harms-and-benefits; cited 27 January 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connor AM. User Manual—Decisional Conflict Scale. Ottawa, ON: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you sure? Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e308–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooke J. sus—a quick and dirty usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland IL, editors. Usability Evaluation in Industry. Bristol, PA: Taylor and Francis; 1996. pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 43.International Association for Public Participation (iap2) IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. Toronto, ON: iap2; 2018. [Available online at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf; cited 18 January 2019] [Google Scholar]