Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose was to test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a 4-session couple-based Intimacy Enhancement (IE) intervention addressing breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns delivered via telephone.

Design/Sample:

Twenty-nine post-treatment breast cancer survivors reporting sexual concerns and their intimate partners were randomized (2:1) to the IE intervention or to an educational control condition, both of which were delivered by trained psychosocial providers.

Methods:

Feasibility and acceptability were measured through recruitment, retention, session completion, and post-intervention program evaluations. Couples completed validated sexual, relationship, and psychosocial outcome measures at pre- and post-intervention. Between-group effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Hedges g.

Findings:

Data supported intervention feasibility and acceptability. For survivors, the IE intervention had medium to large positive effects on all sexual outcomes and most psychosocial outcomes. Effects were less visible for relationship outcomes and were similar but somewhat smaller for partners.

Conclusions:

The IE intervention demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and promise in addressing breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns and enhancing their and their partners’ intimate relationships and psychosocial well-being.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Sexuality, Sexual Dysfunction, Couple Therapy, Interventions

Introduction

Up to 70% of breast cancer survivors report sexual concerns associated with cancer treatments.1 Common breast cancer-related sexual concerns include those that are physical (e.g., vaginal dryness, painful intercourse),2 motivational/emotional (e.g., loss of sexual interest, body image distress),3,4 and interpersonal (e.g., changes in couples’ sexual scripts, loss of sexual activity).5 Some of the most significant sexual sequelae of breast cancer treatments are due to (1) surgeries involving the removal or alteration of the breasts and nipples, which play critical roles for many women in their sexual arousal, body image, and partnered sexual activity,4,6 and (2) hormonal therapy and chemotherapy, which alter women’s sexual hormones and thereby lead to symptoms of vaginal dryness and atrophy and loss of sexual interest.1 Further, breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns tend to persist if unaddressed,7,8 raising the potential for long-term negative effects on individual and relationship well-being.

Yet there are limitations in the interventions available to address breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns. For instance, the most effective medical treatments for women’s sexual dysfunctions are not approved or are contraindicated for breast cancer survivors.9 Physical aids such as vaginal lubricants and moisturizers have amassed supporting efficacy data,10 yet these aids are not adequately comprehensive in that they neither address all physical concerns patients experience (e.g., loss of breast sensitivity from breast and nipple surgeries affecting sexual arousal and pleasure), nor common emotional types of sexual concerns (e.g., body image concerns). Moreover, many women require guidance in successfully integrating physical aids into their intimate relationships. Survivors’ partners also often experience problems related to sex and intimacy, such as worrying they will hurt their partners through engaging in sexual activity or intimate touching.11,12 With this in mind, researchers have suggested that the partner should be integrated into behavioral interventions addressing sexual concerns for partnered breast cancer survivors.13 Yet few existing evidence-based behavioral interventions addressing sexual concerns for breast cancer survivors have systematically involved the intimate partner.

The aim of the current study was to conduct a randomized controlled pilot trial testing Intimacy Enhancement (IE), a couple-based intervention addressing sexual and intimacy concerns of breast cancer survivors administered via telephone. The IE intervention is based on evidence-based sexuality interventions for cancer populations,14 theories of behavioral couples’15 and sex therapy,16 and an approach described previously as flexibility in coping with sexual concerns.17 In two previous pilot studies, promising effects were found on sexual, relationship, and psychosocial outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer and their partners.18,19 The IE intervention was subsequently adapted to address the specific concerns of breast cancer survivors and their intimate partners through a developmental study.11 The objectives of the current study are thus to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the IE intervention in a sample of breast cancer survivors and their intimate partners.

Methods

Participants

Women were eligible if they a) were age ≥ 21 years, b) were in a stable relationship (i.e., living with a romantic partner for ≥ 6 months) that could involve sexual activity,20 c) had completed active treatment 6 months – 5 years ago for non-recurrent Stage I-III breast cancer (current use of endocrine therapy was acceptable), and d) scored ≥ 3 on the Patient Care Monitor sexual concerns screening item, which has been adapted to breast cancer 11 and used as a valid determinant of sexual concerns for cancer survivors.8 Women were excluded if they had a past history of any cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer, an ECOG performance score > 2 (or were judged as being too ill to participate), overt cognitive dysfunction or psychiatric disturbance, were pregnant, or were currently engaged in couple or marital therapy, or if either they or their partner had hearing impairment or were not able to speak English. No exclusions were made based on sexual orientation.

Procedures

Overview of Study Procedures.

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at [INSTITUTION REMOVED].

Enrollment and Data Collection.

Breast cancer survivors were identified through providers’ schedules and the institutional tumor registry. Enrollment began in November, 2015 and continued through July, 2017. Survivors were approached via mailed study introductory letters and follow-up phone calls or in clinic by the study recruiter using a standard script. Consent, baseline, and post-intervention surveys were completed by both members of the couple online using REDCap,21 though paper and pencil forms were available if requested. Post-intervention surveys were administered within several days of the couples’ final session. Couples were reimbursed $25 for completion of each of the two assessments for a possible total of $50 per couple.

Allocation.

Randomization occurred after couples completed baseline surveys. To maximize the amount of information obtained on the IE intervention, couples were randomized using an allocation ration of 2:1 to IE and LHT and a block size of 3 (10 blocks total). Because younger women are at risk for worse sexual impairment,4 couples were randomized with stratification by survivor age at diagnosis (≤ 45 versus > 45). The study biostatistician [INITIALS REMOVED] generated the randomization sequence and the study project manager [INITIALS REMOVED] assigned participants to interventions. Session materials were sent by mail several days prior to the first session and concealed, with written instructions to leave the packets unopened until the first session.

Measures

Feasibility.

Feasibility was measured through rates of study enrollment, retention (i.e., completion of post-intervention study surveys), and session completion.

Acceptability.

The primary acceptability measure was the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8),22 a validated survey of satisfaction with therapeutic services (Cronbach’s alpha=.92). A secondary measure was a program evaluation which assessed (1) the overall ease of participation and helpfulness of the program (0=Not easy/helpful; 4=Extremely easy/helpful), where responses of ≥ 3 (at least “quite a bit easy/helpful”) or were considered positive and (2) agreement to a statement about liking the telephone-based format (1=completely disagree; 10=completely agree), where responses ≥ 8 were considered positive.

Demographic and Medical Data.

Demographic information was collected from participants via self-report. Survivors’ medical data on disease stage, diagnosis date, dates and types of surgeries and other treatments, and menopausal status were obtained via medical review.

Sexual Outcomes.

All participants completed measures of sexual function, satisfaction and self-efficacy; survivors also completed a sexual distress measure. Sexual function for women was assessed using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)23 and for men from the International Index of Erectile Functioning (IIEF).24 Total scores on these measures were used. Cronbach’s alpha was for the FSFI = .98 and .96 for the IIEF. Sexual satisfaction was assessed using the PROMIS SexFS Version 2 Global Sexual Satisfaction Scale,25 a gender-neutral scale referencing the past 30 days with raw scores converted to T scores (M=50; SD=10) against U.S. population norms.25 Greater scores indicate greater satisfaction. Cronbach’s alphas = .93 and .94 for survivors and partners, respectively. Survivors’ sexual distress was assessed using the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R),26 a validated scale used previously in studies of breast cancer survivors27 which captures the degree of distress and dissatisfaction related to a woman’s sex life over the past 30 days (Cronbach’s alpha = .97). Self-efficacy for coping with sexual concerns was assessed using three items assessing participants’ confidence in a) communicating effectively about issues related to physical intimacy/sex; b) dealing effectively with sexual difficulties; and c) enjoying intimacy despite physical limitations. Responses were scored on a 0–100 scale with intervals of 10 and mean scores were used. Cronbach’s alphas were .88 and .89 for survivors and partners, respectively.

Relationship Outcomes.

All participants completed relationship outcome measures. The Dyadic Sexual Communication Scale (DSCS)28,29 assessed perceived quality of communication about sex in the context of the intimate relationship (i.e., sexual communication). Cronbach’s alpha = .83 and .89 for survivors and partners, respectively. Emotional intimacy was assessed using the Emotional Intimacy subscale of the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR),30 which measures feelings of closeness in the context of participants’ intimate relationships. Cronbach’s alpha = .83 and .80 for survivors and partners, respectively. Relationship quality was assessed through the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-7),31 an abbreviated form of the DAS that focuses on consensus in the relationship and correlates well with the full DAS.32 Cronbach’s alpha = .83 and .64 for survivors and partners, respectively.

Psychosocial Outcomes.

All participants completed the Impact of Event Scale-Revised33 which assesses cancer-related distress through measuring intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms; the overall mean score was used. Cronbach’s alphas =.92 and .95 for survivors and partners, respectively. Survivors also completed a body image distress measure, the Body Image Scale (BIS), which was originally validated for use in breast cancer34 and measures distress associated with body changes due to cancer surgery and treatments. Cronbach’s alpha = .93. Finally, survivors’ psychological distress was assessed through depressive symptom and anxiety scales (PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively).35,36 Cronbach’s alphas = .86 and .90 for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively.

Interventions

Interventionists.

Interventionists had at minimum a Master’s degrees in social work or counseling/psychology. Interventionist training included reading relevant scientific literature, participation in an in-person training workshop with written materials, and engaging in trial cases of both conditions with supervision. Sessions were audio recorded and the first author listened to and reviewed each session using pre-set checklists and engaged in weekly supervision with interventionists. Interventionist adherence to the two study intervention manuals was checked on a randomly selected sample of 15% of the study sessions (16 sessions) by independent reviewers on the study team who were not involved in the delivery or supervision of the intervention sessions, using standardized pre-set adherence checklists. Adherence of 85% was set as the benchmark; adherence of 100% was recorded by raters.

Overview of Study Conditions.

Both study conditions consisted of four 60–75 minute weekly sessions delivered by telephone to both members of the couple by a trained interventionist and included session handouts for both survivors and partners sent in advance of the scheduled session. Materials for both conditions were developed to be appropriate to both opposite-sex and same-sex couples. For instance, materials included neutral language (e.g., use of “partner” instead of “husband”) and pictures and graphics (e.g., using clipart that could be appropriate across genders), and for the IE condition, the sexually-relevant content was presented in an inclusive manner (e.g., referring generally to sexual activity rather than to vaginal/penile intercourse). Mean session duration for the IE and LHT conditions were similar (M=70.73, SD=7.54; M=69.94, SD=6.02, respectively), t (27) = .27, p = .77.

Intimacy Enhancement.

As shown in Table 1, the 4-session Intimacy Enhancement (IE) intervention offers survivors and their partners education and skills training to address survivors’ sexual concerns and improve intimacy, defined as an interpersonal process involving mutual sharing and understanding, feelings of closeness, warmth, and affection, and consisting of both physical and emotional aspects.18 The IE intervention is grounded in principles of cognitive therapy, behavioral couple therapy, and sex therapy, as well as in a model of coping with cancer-related sexual concerns that emphasizes coping flexibly through making both behavioral and cognitive shifts.17 Techniques include sensual touching exercises (i.e., sensate focus),37 adapted to incorporate specific instructions for how to deal with thoughts and feelings about breast touching during these exercises, communication skills with regard to sex and intimacy, identifying and challenging overly negative or inflexible sexually-related cognitions, and broadening the repertoire of both sexual and non-sexual intimacy building activities. Each of the four sessions includes a detailed agenda and topic, one or more skills practices in session, and assignment of home practice exercises (see Table 1). Sessions 2 through 4 include a review of the previous week’s home practice.

Table 1.

IE Intervention Session Content

| Session | Session Title | Session Activities | Home Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Intimacy Enhancement |

|

|

| 2 | Improving Intimacy through Communication |

|

|

| 3 | Enhancing Intimacy through Thinking and Doing |

|

|

| 4 | Planning Ahead for Intimacy |

|

|

Living Healthy Together.

The Living Healthy Together (LHT) intervention focuses on delivering education and support across a range of topics relevant to women with breast cancer.38 Topics include education on finding support and the breast cancer experience, what it means to “live healthy together,” (Session 1), stress and stress management (Session 2), fatigue and sleep (Session 3), and diet and nutrition (Session 4). Each session consists of interactive discussion and activities including self-assessment and discussions both with the interventionist and between members of the couple in relation to the session topic.

Statistical Analyses

As this was a pilot study with the aim of measuring IE intervention feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects, a sample size calculation was not conducted. A sample size of 28–30 couples was deemed appropriate to achieve the study objectives. Using data from prior intervention studies as a guide,19,39,40 feasibility benchmarks were defined as an accrual rate ≥ 30% (though accrual > 20% was considered acceptable), retention ≥ 70%, and session completion of ≥ 80%. Acceptability was defined as a group median score ≥ 28 on the CSQ-8. Program evaluation items were analyzed descriptively. In addition, independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare CSQ-8 scores across the study conditions. Baseline comparisons were conducted across study conditions for survivors and partners separately on outcome measures using independent t-tests. All couples with post-intervention data were included in data analyses, regardless of the number of intervention sessions completed; data from one couple who did not complete the post-intervention survey were excluded. As recommended for pilot trials, we did not conduct statistical tests of group differences on outcome measures41,42 but rather calculated pre- to post-treatment change scores for each participant, along with mean change scores and 95% confidence intervals. Between-group effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals around these effect sizes were calculated using the Hedges g statistic, a t-type statistic with a correction for bias that occurs when using Cohen’s d. The statistical package R and procedure compute.es were used to obtain these values.43,44 Other analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20. Per convention, effect sizes were classified as small (.20), medium (.50), and large (.80).45

Results

Participants

Baseline demographic and medical data for study completers are presented in Table 2. Survivors were mostly Caucasian, highly educated, and working at least part time. All but one of the partners were opposite-sex and were similar to survivors in age, race, and education.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Total | IE | LHT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Survivors (N=28) M (SD) |

Partners (N=28) M (SD) |

Survivors (N=19) M (SD) |

Partners (N=19) M (SD) |

Survivors (N=9) M (SD) |

Partners (N=9) M (SD) |

| Age | 54.1 (10.8) | 54.8 (10.0) | 54.8 (10.4) | 55.1 (10.4) | 52.7 (12.3) | 54.0 (9.5) |

| Sexual concerns [0–10] | 6.0 (2.4) | 5.9 (2.2) | 6.3 (3.0) | |||

| Length of relationship (years) | 25.9 (14.1) | 29.0 (12.5) | 19.6 (16.0) | |||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 32.1 (15.8) | 34.6 (16.3) | 26.7 (14.0) | |||

| Time since treatment completion (months) | 22.7 (14.3) | 24.6 (14.5) | 18.7 (14.0) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | ||||||

| No comorbidities | 20 (71.4%) | 21 (75%) | 12 (63.2%) | 15 (78.9%) | 8 (88.9%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| One comorbidity | 6 (21.4%) | 6 (21.4%) | 5 (26.3%) | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| Two or more comorbidities | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 25 (89.3%) | 24 (85.7%) | 17 (89.5%) | 16 (84.2%) | 8 (88.9%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| Black/African American | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| More than one race | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education | ||||||

| High School or GED | 4 (14.3%) | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (15.8%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Some college | 6 (21.4%) | 6 (21.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Completed college/Graduate school | 18 (64.3%) | 19 (67.8%) | 13 (68.4%) | 12 (63.2%) | 5 (55.6%) | 7 (77.8%) |

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Full/Part Time | 18 (64.3%) | 21 (75%) | 11 (57.9%) | 12 (63.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | 9 (100%) |

| Retired | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Self-employed | 3 (10.7%) | 3 (10.7%) | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unemployed/on disability/other | 4 (14.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual/Straight | 27 (96.4%) | 19 (100%) | 8 (88.9%) | |||

| Homosexual/Lesbian | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | |||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 27 (96.4%) | 19 (100%) | 8 (88.9%) | |||

| Living with a significant partner but not married | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) | |||

| Menopausal Status | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (22.2%) | |||

| Perimenopausal | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | |||

| Post-menopausal | 22 (78.6%) | 16 (84.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | |||

| Disease stage | ||||||

| Stage I | 12 (42.9%) | 6 (31.6%) | 6 (66.7%) | |||

| Stage II | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | |||

| Stage III | 5 (17.9%) | 5 (26.3%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Primary Surgery | ||||||

| Lumpectomy | 17 (60.7%) | 11 (57.9%) | 7 (77.8%) | |||

| Mastectomy | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | |||

| Treatments Received | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 17 (60.7%) | 14 (73.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | |||

| Radiation | 21 (75%) | 15 (78.9%) | 6 (66.7%) | |||

| Hormonal Therapy | 22 (78.6%) | 14 (73.7%) | 8 (88.9%) | |||

| Tamoxifen | 9 (32.1%) | 6 (27.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | |||

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 13 (46.4%) | 8 (36.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | |||

Feasibility

Study Enrollment and Participation.

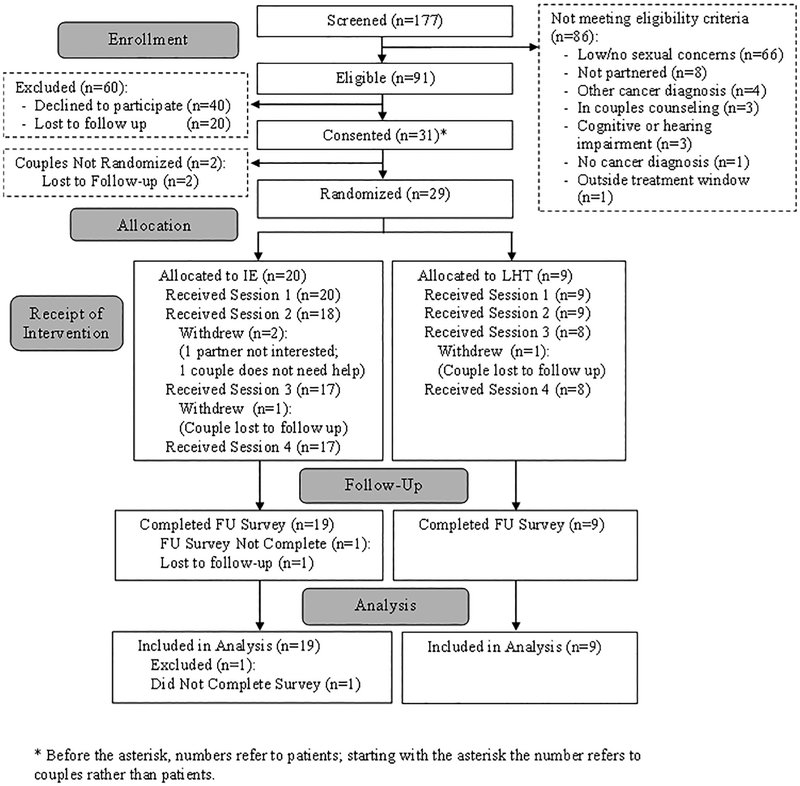

The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. All feasibility measures met or exceeded benchmarks set during study design. Accrual rates for the study were 34% for consent and 32% for randomization. Study retention was 97%; all but one couple completed both sets of study surveys. Of the 20 couples randomized to receive the IE intervention, 17 (85%) completed all four sessions.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Acceptability

Satisfaction.

The median CSQ-8 score for IE participants was 31.0, exceeding the pre-set benchmark of 28. Mean CSQ-8 scores across both study conditions were very good; IE participants reported higher satisfaction (M=30.0; SD=2.3) as compared to LHT participants (M=25.5; SD=4.7), t (52) = - 3.87, p = .001.

Post-Intervention Program Evaluation.

Most IE participants rated the IE intervention as being easy to participate in and helpful (91.7% for both items). The majority reported liking the telephone format (86.1%).

Preliminary Efficacy

Study Group Comparisons.

There were no significant differences on any baseline outcome measures either for survivors (p values > .18) or for partners (p values ≥ .20).

Effect Sizes for Survivors.

Baseline and post-treatment means, confidence intervals around the means, group-wise differences in change scores, along with confidence intervals, and effect sizes with confidence intervals for survivors and partners are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Large effects were found in the anticipated directions for all four sexual outcomes. For the relationship outcomes, there was a medium to large effect seen for an increase in sexual communication, no effect for emotional intimacy, and a small to medium effect seen for reduction in relationship quality. For the psychosocial outcomes, a small effect was found for a reduction in body image distress, a small to medium effect for a reduction in cancer-related distress, a medium to large effect for reduction in depressive symptoms, and a large effect for a reduction in anxiety symptoms.

Table 3.

Means, Differences, Effect Sizes, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) on Study Measures for Survivors

| Survivors (N=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE (N=19) |

LHT (N=9) |

Difference‡ | Effect Size | |

| Mean (95% CI) |

Mean (95% CI) |

Mean (95% CI) |

Effect Size (95% CI) |

|

| Sexual Outcomes | ||||

| Sexual Function – Female (FSFI) | -- | -- | 10.14 (3.37, 16.90) | 1.24 (0.37, 2.18) |

| Baseline | 14.26 (9.23, 19.30) | 20.02 (12.45, 27.60) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 24.02 (19.80, 28.24) | 19.64 (10.99, 28.29) | -- | -- |

| Sexual Satisfaction (PROMIS SexFS) | -- | -- | 10.14 (5.45, 14.82) | 1.75 (0.83, 2.77) |

| Baseline | 41.08 (37.26, 44.90) | 44.98 (38.62, 51.34) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 48.46 (45.36, 51.56) | 42.22 (36.72, 47.72) | -- | -- |

| Sexual Distress (FSDS-R) | -- | -- | −7.77 (−15.10, −0.44) | −0.87 (−1.77, −0.03) |

| Baseline | 25.16 (18.52, 31.80) | 28.22 (17.15, 39.29) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 15.95 (10.49, 21.41) | 26.78 (16.29, 37.27) | -- | -- |

| Self-Efficacy | -- | -- | 24.72 (8.05, 41.38) | 1.21 (0.34, 2.14) |

| Baseline | 58.25 (45.76, 70.73) | 60.00 (39.83, 80.18) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 83.33 (77.44, 89.22) | 60.37 (42.74, 78.00) | -- | -- |

| Relationship Outcomes | ||||

| Sexual Communication (DSCS) | -- | -- | 9.14 (−1.68, 19.97) | 0.71 (−0.12, 1.59) |

| Baseline | 53.50 (47.73, 59.28) | 57.22 (47.94, 66.50) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 62.32 (58.07, 66.56) | 56.89 (49.15, 64.63) | -- | -- |

| Emotional Intimacy (PAIR) | -- | -- | 0.03 (−0.51, 0.57) | 0.04 (−0.79, 0.88) |

| Baseline | 3.56 (3.20, 3.92) | 3.74 (3.10, 4.38) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 3.87 (3.55, 4.18) | 4.02 (3.74, 4.29) | -- | -- |

| Relationship Quality (DAS-7) | -- | -- | −1.65 (−6.13, 2.83) | −0.32 (−1.17, 0.50) |

| Baseline | 24.53 (21.94, 27.11) | 25.67 (19.80, 31.53) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 25.21 (23.19, 27.23) | 28.00 (24.72, 31.28) | -- | -- |

| Psychosocial Outcomes | ||||

| Body Image Distress (BIS) | -- | -- | −0.85 (−5.29, 3.58) | −0.17 (−1.00, 0.66) |

| Baseline | 10.05 (6.35, 13.76) | 11.00 (4.49, 17.51) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 7.42 (4.06, 10.78) | 9.22 (3.58, 14.87) | -- | -- |

| Cancer-related Distress (IES-R) | -- | -- | −3.65 (−11.76, 4.46) | −0.37 (−1.22, 0.46) |

| Baseline | 17.00 (9.22, 24.78) | 16.00 (8.72, 23.28) | -- | |

| Follow-up | 11.68 (5.41, 17.96) | 14.33 (5.69, 22.98) | -- | |

| Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9) | -- | -- | −1.95 (−4.36, 0.46) | −0.66 (−1.54, 0.17) |

| Baseline | 5.58 (2.85, 8.31) | 5.11 (1.11, 9.11) | -- | |

| Follow-up | 3.63 (1.71, 5.55) | 5.11 (1.26, 8.96) | -- | |

| Anxiety Symptoms (GAD-7) | -- | -- | −4.85 (−7.88, .1–81) | −1.36 (−2.32, −0.48) |

| Baseline | 4.84 (2.34, 7.35) | 3.44 (1.01, 5.88) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 3.11 (1.35, 4.86) | 6.56 (2.75, 10.36) | -- | -- |

This is the difference of IE versus LHT on change score (follow-up minus baseline on study measures) where positive difference means indicate scores in the IE group increased more on this measure than in the LHT group.

Table 4.

Means, Differences, Effect Sizes, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) on Study Measures for Partners

| Partners (N=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE (N=18) |

LHT (N=9) |

Difference | Effect Size | |

| Mean (95% CI) |

Mean (95% CI) |

Mean (95% CI) |

Effect Size (95% CI) |

|

| Sexual Outcomes and Coping | ||||

| Sexual Function – Male (IIEF) | -- | -- | 7.83 (0.70, 14.96) | 0.89 (0.05, 1.79) |

| Baseline | 49.42 (38.26, 60.59) | 58.75 (47.68, 69.82) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 54.68 (44.80, 64.56) | 57.00 (42.83, 71.17) | -- | -- |

| Sexual Satisfaction (PROMIS SexFS) | -- | -- | 2.83 (−1.68, 7.34) | 0.52 (−0.31, 1.38) |

| Baseline | 44.78 (40.99, 48.58) | 48.22 (41.24,55.25) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 48.66(44.52, 52.80) | 49.29 (40.27, 58.32) | -- | -- |

| Self-Efficacy | -- | -- | 9.43 (−3.99, 22.85) | 0.57 (−0.26, 1.43) |

| Baseline | 68.78 (56.32, 81.22) | 75.19 (56.97, 93.40) | -- | |

| Follow-up | 80.70 (72.68, 88.73) | 74.58 (58.13, 91.03) | -- | |

| Relationship Outcomes | ||||

| Sexual Communication (DSCS) | -- | -- | 1.40 (−4.69, 7.50) | 0.19 (−0.64, 1.03) |

| Baseline | 55.16 (49.06, 61.26) | 53.67 (44.61, 62.72) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 59.89 (54.31, 65.48) | 57.00 (44.65, 69.35) | -- | -- |

| Emotional Intimacy (PAIR) | -- | -- | −0.27 (−0.80, 0.26) | −0.44 (−1.29, 0.39) |

| Baseline | 4.14 (3.91, 4.37) | 3.91(3.21, 4.60) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 4.00 (3.69, 4.31) | 4.04 (3.52, 4.55) | -- | -- |

| Relationship Quality (DAS-7) | -- | -- | 0.51 (−4.09, 5.12) | 0.10 (−0.73, 0.93) |

| Baseline | 24.47 (22.61, 26.34) | 26.00 (22.12, 29.88) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 25.21 (23.51, 26.91) | 26.22 (22.25, 30.19) | -- | -- |

| Psychosocial Outcomes | ||||

| Cancer-related Distress (IES-R) | -- | -- | −1.57 (−14.18, 11.05) | −0.11 (−0.94, 0.72) |

| Baseline | 9.05 (2.70, 15.41) | 15.56 (1.98, 29.13) | -- | -- |

| Follow-up | 7.26 (2.27, 12.26) | 15.33 (6.96, 23.71) | -- | -- |

This is the difference of IE versus LHT on change score (follow-up minus baseline on study measures) where positive difference means indicate scores in the IE group increased more on this measure than in the LHT group.

Effect Sizes for Partners.

Data from partners showed a large effect for an increase in sexual function, and medium effects for increases in sexual satisfaction and self-efficacy. There were small effects for an increase in sexual communication and relationship quality, whereas there was a small to medium effect for a reduction in emotional intimacy. There was also a small effect for a reduction in cancer-related distress.

Discussion

Findings from this study strongly support the feasibility and acceptability of the Intimacy Enhancement (IE) intervention for breast cancer survivors and their partners. Researchers have noted challenges in recruiting cancer survivors and their partners to trials of behavioral interventions,46,47 with additional hurdles posed by interventions focusing on sex and intimacy.39,48 In the current study, the benchmarks set for study recruitment and retention and for completion of IE sessions were either met or exceeded. Evidence of good acceptability was also found; in post-intervention surveys, over 90% of IE participants reported that the IE intervention was both easy to participate in and helpful in improving the intimacy in their relationship. These encouraging findings suggest that the IE intervention was well-received by breast cancer survivors who reported having sexual concerns and their intimate partners.

Results of the current study suggested that survivors who received the IE intervention showed greater improvements on a range of sexual QOL outcome measures when compared to those in the control condition. The IE intervention also showed promise in improving partners’ sexual function, satisfaction, and self-efficacy. By providing both members of the couple with skills for coping with breast cancer effects on the intimate relationship, the IE intervention could lead to more sustained and effective coping efforts and therefore to long-term improvement in survivors’ sexual outcomes.

The promise of the IE intervention for improving survivors’ and partners’ sexual outcomes is particularly noteworthy in light of several features of the study. First, at four sessions, the IE intervention is relatively brief. This could make the IE intervention appealing to survivors faced with the daunting tasks of meeting health demands while resuming work, family, and social responsibilities, and who may therefore appreciate brief approaches to addressing their sexual concerns. Second, the IE intervention is delivered by telephone. Like recent web-based interventions addressing sexual concerns for cancer survivors,27,39 a telephone delivery eliminates the burden of travel and increases convenience. Yet considering that as many as 41% of older adults do not use the internet,49 a telephone delivery may hold particular appeal in that it does not require internet use or computer literacy. The telephone may also be preferable to traditional face-to-face formats for discussing sensitive topics such as sexuality19 because it may feel more anonymous to participants. Third, whereas prior studies of sexual QOL interventions in women with cancer have generally not included an active control group as the comparator,50 all couples in the study engaged in four joint sessions with a counselor. The positive effects of the IE intervention can therefore not be attributed to time and attention from a skilled counselor.

As compared to the strong preliminary effects on sexual outcomes, the effects of the IE intervention for general relationship outcomes were not uniformly positive. There are several possible explanations for these findings. Whereas survivors had to screen in as having at least mild sexual concerns in order to enroll, most couples had above-average relationship quality at enrollment, suggesting the possibility of a ceiling effect. Indeed, it is possible that improving sexual outcomes for couples who entered the study with already very high relationship quality might have alleviated distress and anxiety that could have been associated with these problems but might not necessarily have improved general relationship outcomes, which were already high to start. Some couples – even those who had been married for decades – reported during sessions that this study represented the first time they had discussed their sexual relationship at considerable length. Under these circumstances, some mild discomfort at discussing challenges in the intimate relationship would not be surprising. In future research, it would be important to examine whether improving couples’ sexual outcomes could lead to improvements in broader relationship outcomes over time using long-term follow-up assessments, particularly for couples whose relationships had suffered due to unaddressed sexual problems.

An intriguing finding concerns the large effects seen for the IE intervention on survivors’ depressive and anxiety symptoms. Through offering coping tools for addressing long-standing or distressing sexual concerns, as well as skills such as cognitive restructuring, the IE intervention could have reduced survivors’ general feelings of distress.17 In addition, a small positive effect was seen for a reduction in survivors’ body image distress. This may be due to survivors’ engagement in sensate focus exercises, which expose survivors to partnered bodily touching gradually and might serve as a powerful tool for reducing bodily avoidance while facilitating positive feelings about the body (e.g., the body can be a source of pleasure).

This study had several strengths including an active control condition, the monitoring of intervention fidelity, the use of validated measures assessing intervention acceptability and a range of survivors’ and partners’ outcomes, excellent participant retention, and the screening of patients who have sexual concerns, which may have served to strengthen the effects of the IE intervention. Yet there are several study limitations. The major limitation is the small sample size, which leads to the potential for skewed group means on outcome measures. For this reason, confidence intervals are provided and the effect sizes should be viewed with caution. In addition, there was no long-term follow-up, which precludes demonstration of the maintenance of treatment effects. A large trial of the IE intervention is currently being planned which will be powered to find significant intervention effects and will include follow-up assessments over one year. In addition, the IE intervention was developed for partnered breast cancer survivors. Additional work is needed to understand the sexual health needs of breast cancer survivors who are not in partnered relationships so that appropriate interventions can be developed for these survivors.51 Moreover, although same-sex couples were invited to participate, only one same-sex couple enrolled, and thus, it is not possible to generalize findings to same-sex couples. Finally, the sample was primarily white, despite efforts to achieve greater racial and ethnic diversity. Strategies are being developed to enhance the diversity of the sample for the planned larger trial such as partnering with local leaders within the Black and Hispanic communities for recruitment. We also plan to work with literacy experts to increase the broad accessibility of the IE intervention. These efforts could enhance recruitment overall as well as bolster the generalizability of effects with respect to literacy levels of the target population.

Conclusion

Findings from this pilot study suggest that a couple-based intervention focused on sexuality and intimacy is a feasible, acceptable, and promising approach for addressing sexual concerns for breast cancer survivors and enhancing survivors’ intimate relationships. Sexual outcomes continue to be among the most problematic and distressing of the QOL effects of cancer treatments for breast cancer survivors. Interventions that can address these concerns effectively will be of interest to the growing number of breast cancer survivors living for many years after their diagnosis.

Implications for Psychosocial Oncology Practice:

The IE intervention demonstrated feasibility and acceptability, suggesting it could be well-received by breast cancer survivors with sexual concerns and their partners.

Effects of the IE intervention on breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns and on their and their partners’ intimate relationships and psychosocial well-being could not be attributed to therapist time and attention.

Interventions that psychosocial providers can use to address breast cancer survivors’ sexual concerns are important to the growing number of breast cancer survivors living for many years after their diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NCI R21CA191354 and P30CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute. The authors have no relationships that might bias this work or any conflicts of interest to report. The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (entry NCT02721147, Pilot Study of an Intimacy Enhancement Intervention for Couples Facing Breast Cancer).

References

- 1.Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Sexual Function after Breast Cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8(1):294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ussher J, Perz J, Gilbert E. Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(6):456–464. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182395401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of Life Among Younger Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang SB, D’Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):579–594. doi: 10.1002/Pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loaring JM, Larkin M, Shaw R, Flowers P. Renegotiating sexual intimacy in the context of altered embodiment: The experiences of women with breast cancer and their male partners following mastectomy and reconstruction. Health Psychol. 2015;34(4):426–436. doi: 10.1037/hea0000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, et al. Cancer and Sexual Problems. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1):349–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz PA, Desmond A, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese JB, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Abernethy AP. Sexual concerns in cancer patients: a comparison of GI and breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(9):1179–1189. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0738-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):43–73. doi: 10.3322/caac.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter J, Stabile C, Seidel B, Baser RE, Goldfarb S, Goldfrank DJ. Vaginal and sexual health treatment strategies within a female sexual medicine program for cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(2):274–283. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese JB, Porter LS, Casale KE, et al. Adapting a couple-based intimacy enhancement intervention to breast cancer: A developmental study. Health Psychol. 2016;35(10):1085–1096. doi: 10.1037/hea0000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahlis EH, Lewis FM. Coming to Grips with Breast Cancer: The Spouse’s Experience with His Wife’s First Six Months. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28(1):79–97. doi: 10.1080/07347330903438974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll AJ, Baron SR, Carroll RA. Couple-based treatment for sexual problems following breast cancer: A review and synthesis of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3651–3659. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2689–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein NB, Baucom DH, eds. Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Couples: A Contextual Approach. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association (APA) 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiblum SR. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reese JB, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Abernethy AP. Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: the use of flexible coping. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(7):785–800. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0819-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reese JB, Porter LS, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ. Pilot feasibility study of a telephone-based couples intervention for physical intimacy and sexual concerns in colorectal cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 2012;38(5):402–417. doi: 10.1080/0092623x.2011.606886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barsky Reese J, Porter LS, Regan KR, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a telephone-based couples intervention for physical intimacy and sexual concerns in colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23(9):1005–1013. doi: 10.1002/pon.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PROMIS Sexual Function User Manual. 2011; http://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/Sexual%20Function%20Manual.pdf. Accessed 4/17/12, 2012.

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–830. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner DW, et al. Development and Initial Validation of the PROMIS® Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures Version 2.0. J Sex Med. 2015;12(9):1961–1974. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeRogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised for Assessing Distress in Women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hummel SB, van Lankveld JJ, Oldenburg HS, et al. Efficacy of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Improving Sexual Functioning of Breast Cancer Survivors: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017: 10.1200/jco.2016.69.6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catania JA. Help-seeking: An avenue for adult sexual development. University of California, San Francisco; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catania J Dyadic Sexual Communication Scale In: Fisher TD, Davis CM, Yarber WL, Davis SL, eds. Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures. Routledge: New York; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaefer MT, Olson DH. Assessing Intimacy: The Pair Inventory. J Marital Fam Ther. 1981;7(1):47–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1981.tb01351.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunsley J, Best M, Lefebvre M, Vito D. The Seven-Item Short Form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Further Evidence for Construct Validity. Am J Fam Ther. 2001;29(4):325–335. doi: 10.1080/01926180126501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunsley J, Pinsent C, Lefebvre M, James-Tanner S, Vito D. Construct validity of the short forms of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Family Relations. 1995;44(3):231. doi: 10.2307/585520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised In: Wilson JP KE TM, ed. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook. New York: Guilford; 1997:399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi:jgi01114 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown & Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cancer Support Community Cancer Experience Registry Index Report 2017. https://www.cancersupportcommunity.org/sites/default/files/uploads/our-research/2017_Report/the_bc_specialty_report_7-10.pdf?v=1. Accessed 02/03/2018.

- 39.Schover LR, Yuan Y, Fellman BM, Odensky E, Lewis PE, Martinetti P. Efficacy trial of an internet-based intervention for cancer-related female sexual dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(11):1389–1397. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen A, Atkins DC, Berns S, Wheeler J, Baucom DH, Simpson LE. Traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy for significantly and chronically distressed married couples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(2):176–191. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, et al. Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2:64. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Re AC. compute.es: Compute Effect Sizes. R package version 0.2–2. 2013.

- 44.Bornstein M Effect Sizes for Continuous Data In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The handbook of research synthesis and meta analysis. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 2009:279–293. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fredman SJ, Baucom DH, Gremore TM, et al. Quantifying the recruitment challenges with couple-based interventions for cancer: applications to early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(6):667–673. doi: 10.1002/pon.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmstrom AJ, Wyatt GK, Sikorskii A, Musatics C, Stolz E, Havener N. Dyadic recruitment in complementary therapy studies: experience from a clinical trial of caregiver-delivered reflexology. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DuHamel K, Schuler T, Nelson C, et al. The sexual health of female rectal and anal cancer survivors: results of a pilot randomized psycho-educational intervention trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson MP, A. 13% of Americans don’t use the internet. Who are they? 2016; http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/07/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/. Accessed November 9, 2016.

- 50.Candy B, Jones L, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, King M. Interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD005540. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005540.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw L-K, Sherman KA, Fitness J, Breast Cancer Network A. Women’s experiences of dating after breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2016;34(4):318–335. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2016.1193588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]