Abstract

Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) is a rare interstitial lung disease characterized by the fibrotic thickening of subpleural and parenchymal areas of the upper lobes. It may be both idiopathic or secondary to infections, interstitial lung diseases and/or drug exposure. Often PPFE patients report recurrent lower respiratory tract infections, suggesting that repeated inflammatory alterations induced by pulmonary infections may contribute to the development/progression of PPFE.

Here, we report for the first time the case of a patient affected by Giant cell Arteritis with histologically proven PPFE. The lung involvement in GCA is rare and interstitial lung diseases are usually reported as an uncommon clinical manifestation of GCA. Our patient is probably the first case presenting PPFE associated with GCA and we wonder if this is a real associative disease or a coincidence perhaps, secondary to drug effects.

Keywords: Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, Giant cell arteritis, Diagnosis

Abbreviations: Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis, PPFE; high resolution computed tomography of the chest, HRCT; magnetic resonance, MRI; positron emission tomography, PET; light scattering spectroscopy, LSS

1. Introduction

Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) is a rare interstitial lung disease (ILD) characterized by a fibrotic thickening of subpleural and parenchymal areas of the upper lobes [1]. It was firstly described in 1992 [2] and, according to updated ATS/ESR guidelines [3], PPFE can be considered an idiopathic ILD with no clear relationship with smoking exposure [4,5]. PPFE may be associated with infections, interstitial lung diseases and/or drug exposure. PPFE can occur consequently to lung, bone marrow, hematopoietic cell transplantation [6], immunosuppressive treatments [7,8] or occupational exposures to silicate dust and asbestos [9]. Often, PPFE patients report recurrent lower respiratory tract infections, suggesting that repeated inflammatory injuries induced by pulmonary infections may contribute to the pathogenesis of PPFE. The disease may also be associated with different ILDs, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) [[10], [11], [12]]. Especially in young females, PPFE can occur in the context of familial forms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP), suggesting a potential role of a genetic predisposition in its development [13,14]. Common symptoms of PPFE include dyspnea, dry cough and weight loss; in the course of the disease some patients can be affected by spontaneous pneumothorax [5,16]. As a rule, PPFE is associated with a restrictive functional deficit and an impairment of CO diffusion capacity (DLCO) [5], which are considered the principal prognostic biomarkers of disease progression [17,18]. Radiological features include pleural fibrotic thickening and subpleural fibroelastosis, with an upper lobe predominance associated with traction bronchiectasis, architectural distortion, loss of volume and reticulations [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. In advanced stages of disease, the architectural distortion can involve also adjacent and lower lobes. Histopathologic features include aggregates of elastic fibers, especially in the sub-pleural areas, and intra-alveolar collagenous fibrosis with septal elastosis (with or without collagenous thickening of the visceral pleura) [20,22]. The interface with uninvolved parenchyma is typically abrupt; the architectural distortion mainly occurs in sub-pleural areas but a peri-bronchial distribution has also been reported [21]. PPFE diagnostic criteria have been postulated only 2 years ago and include the detection of multilobar subpleural and/or centrilobular fibrous interstitial pneumonia with an extensive (>80%) proliferation of elastic fibers in non-atelectasis lung [22].

Here, we report for the first time the case of a patient affected by Giant Cell Arteritis with histologically proven PPFE.

2. Case report

2.1. Clinical and functional parameters

A 63 years old never smoker male patient, with no professional exposure (hunter for hobby) and a positive family history for IPF (his brother died for acute exacerbation of IPF), was referred to the emergency room of our Centre reporting asthenia, fever and recurrent episodes of headache in the last seven months. A physical examination revealed no remarkable clinical signs, including normal chest sounds. The patient had no evidence of cutaneous or ocular disease. Brain MRI was normal as well as FDG PET/CT.

Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) was hypothesized according to rheumatologic evaluation, increased serum C-reactive protein levels (8.06 mg/dl) and neutrophilic leucocytosis. During the hospitalization, the patient had an episode of amaurosis fugax and “Horton's Arteritis” diagnosis was confirmed. He was treated with oral steroids and methotrexate: however, after 2 months of treatment was referred to the pulmonology unit for a persistent dry cough and recurrent fever. Physical examination was normal; lung function tests revealed a mild functional restrictive impairment (FVC 81%, FEV1 80%, TLC 67% of predicted values) associated with a severe reduction of carbon monoxide diffusion (39% of predicted value).

2.2. Radiological features

Chest X-ray revealed widespread accentuation of the pulmonary interstitium.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed a micronodular pattern with peribronchovascular distribution, bilateral intense pleural and sub-pleural fibrosis, interlobular septal thickening and traction bronchiectasis, predominantly in the upper lobes. There were no honeycombing areas. No evidence of disease was found in the middle and in the lower lobes (Fig. 1).

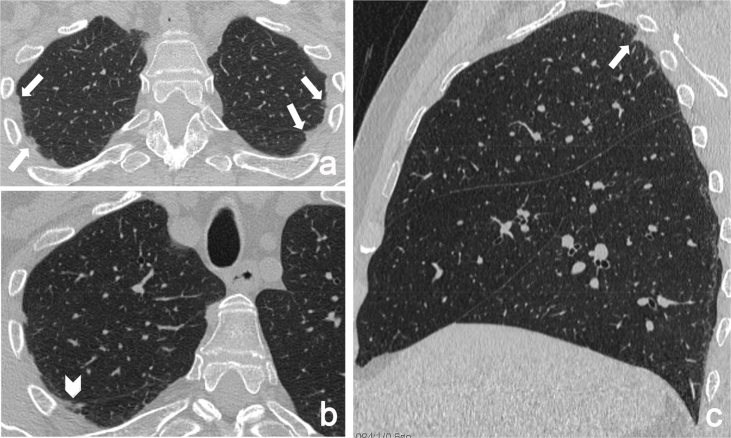

Fig. 1.

HRCT axial images (a, b) and sagittal multiplanar reconstructions (c) show pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, involving the dorsal regions of upper lobes (arrows) and the right fissure (arrowhead).

2.3. Laboratory data

C-reactive protein levels were still increased (4.62 mg/100 ml); ACE, lysozyme and chitotriosidase were in the normal range. No serological evidence of connective tissue disease was found. Diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed: the analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) showed normal microbiological condition. The cellular analysis of BAL showed 2.800.000 total cells, with a percentage of 46% macrophages, 45% lymphocytes with CD4/CD8 ratio 2.49, and 9% neutrophils.

2.4. Histological evaluation

The patient stopped methotrexate and continued steroid therapy and empiric antibiotics; however, in the following three months, he still referred dry cough, unresponsive to steroids and other treatments. Subsequently, the patient underwent a surgical lung biopsy (VATS) and histological observations with light scattering spectroscopy (LSS) showed dense collagenous fibrosis with concomitant elastosis of the visceral pleura and the lung parenchyma, affecting peribronchial and peribronchiolar tissue. Visceral pleura was highly thickened by a mixture of elastic and dense collagen fibers. Mild deposition of silica was observed without non-necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

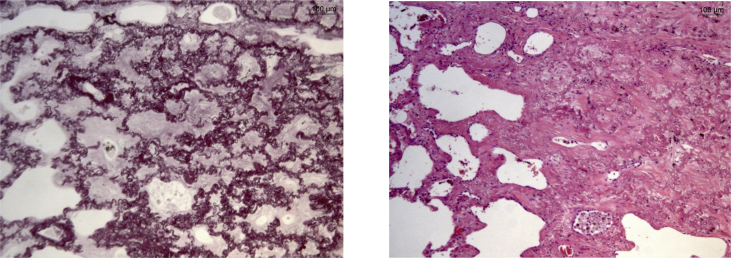

Fig. 2.

Histological evaluation of VATS sampling. Pleural fibroelastosys clearly separated from lung parenchymal tissue (on the left, hematoxylin-eosin staining; on the right, Weigert staining).

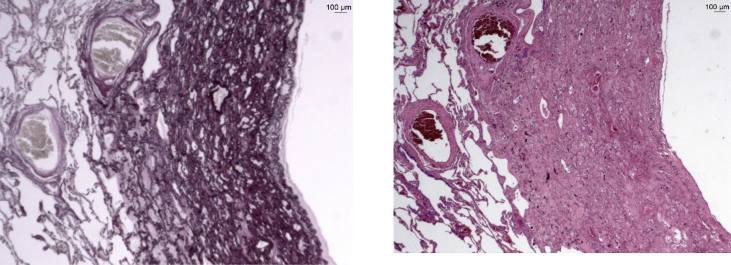

Fig. 3.

PPFE infiltration of lung parenchyma (on the left, hematoxylin-eosin staining; on the right, Weigert staining).

After the multidisciplinary discussion for the evaluation of clinical, radiological and histological features of the patients, the diagnosis of PPFE was confirmed.

3. Discussion

PPFE has never been associated with giant cell arteritis and, as far as we know, only two GCA patients with interstitial lung diseases have been described in the literature. Karam et al., in 1982 reported a case of a patient with GCA without specific interstitial lung involvement and no PPFE evidence [23] while more recently Konoshi et al. described a clinical case without PPFE evidence at HRCT [24]. The lung involvement in GCA is rare and interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are usually reported as an uncommon clinical manifestation of GCA [25]. Our patient is probably the first case presenting PPFE associated with GCA and we wonder if this is a real associative disease or a coincidence, perhaps secondary to drug effects.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

The present research was performed at Siena University without funding sponsors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100843.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.English J.C., Mayo J.R., Levy R., Yeee J., Leslie K.O. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: a rare interstitial lung disease. Respirol. Case Rep. 2015 Jun;3(2):82–84. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amitani R., Kuse F. Idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis (IPUF) Kokyu. 1992;11:693–699. [Google Scholar]

- 3.ATS/ERS committee on idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European respiratory society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013 Sep 15;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryu J.H., Colby T.V., Hartman T.E., Vassallo R. Smoking-related interstitial lung diseases; a concise review. Eur. Respir. J. 2001;17:122. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17101220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe W. vol. 9. 2013. pp. 229–237. (Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis: its Clinical Characteristics Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mariani F., Gatti B., Rocca A. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: the prevalence of secondary forms in hematopoietic stem cell and lung transplantation recipients. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2016;22(5):400–406. doi: 10.5152/dir.2016.15516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beynat-Mouterde C., Bel t ramo G., Lezmi G. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis as a late complication of chemotherapy agents. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44(2):523–527. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00214713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baroke E., Heussel C.P., Warth A. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis in association with carcinomas. Respirology. 2016;21(1):191–194. doi: 10.1111/resp.12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Z., Li S., Zhu Y. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis associated with aluminosilicate dust: a case report. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8(7):8676–8679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy T.L., Tominaga M., Hansell D.M. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: a spectrum of histopathological and imaging phenotypes. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;40(2):377–385. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oda T., Ogura T., Kitamura H. Distinct characteristics of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis with usual interstitial pneumonia compared with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2014;146(5):1248–1255. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2866. This report firstly provides data on prevalence and prognostic implication of PPFE pattern in IPF patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakatani T., Arai T., Kitaichi M. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis from a consecutive database: a rare disease entity. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;45(4):1183–1186. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00214714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel S.K., Cool C.D., Lynch D.A. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: description of a novel pathologic entity. Chest. 2004;126(6):2007–2013. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E., Paugam B., Heymann M.F. Familial extensive idiopathic bilateral pleural fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 1999;14(4):971–973. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d41.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusagaya H., Nakamura Y., Kono M. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: consideration of a clinicopathological entity in a series of Japanese patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2012;12:72–74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zappala C.J., Latsi P.I., Nicholson A.G. Marginal decline in forced vital capacity is associated with a poor outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;35:830–836. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00155108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusagaya H., Nakamura Y., Kono M. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: consideration of a clinicopathological entity in a series of Japanese patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2012;12:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker C.D., Gil J., Padilla M.L. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: an unrecognized or misdiagnosed entity? Mod. Pathol. 2008;6:784–787. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piciucchi S., Tomassetti S., Casoni G. High resolution CT and histological findings in idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: features and differential diagnosis. Respir. Res. 2011;12:111–115. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes P.S., Shiang C., Szarf G. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: report of two cases in Brazil. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2017 Jan-Feb;43(1):72–75. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37562016000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum J.N., Butt Y.N., Johnson K.A. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: a pattern of chronic lung injury. Hum. Pathol. 2015 Jan;46(1):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karam G.H., Fulmer J.D. Giant cell arteritis presenting as interstitial lung disease. Chest. 1982;82:781–784. doi: 10.1378/chest.82.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konishi C. Interstitial lung disease as an initial manifestation of giant cell arteritis. Intern. Med. 2017;56(19):2633–2637. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.8861-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bargagli E., Rottoli P., Torricelli E. Airway-centered PPFE associated with non necrotizing granulomas: a rare new entity. Pathobiology. 2018;85:276–279. doi: 10.1159/000492431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.