Abstract

Background

In Japan, incidence of gastric cancer is expected to follow the current downward trend as the younger generation has lower incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. In this study we aimed to estimate how long gastric cancer screening is deemed necessary in the future from epidemiologic perspectives.

Methods

Following the Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening 2014, recommendation of providing population-based gastric cancer screening is judged by balancing benefits and harms. Benefits and harms are estimated by number needed to screen (NNS) < 1000 and Number Needed to Recall (NNR) < 100. NNS is the number of people required to participate in a screening to prevent one death and NNR is the number of people required to undergo diagnostic examination to prevent one death. These index are estimated for 2020–2035 using future projections of gastric cancer mortality for the scenarios of relative risk (RR) of 0.5–0.9 for mortality reduction by the screening.

Results

The criteria of both NNS < 1000 and NNR < 100 are fulfilled for the following age groups: when RR is set as 0.6, men ≥ 55 and women ≥ 65; when RR is set as 0.7 and 0.8, men ≥ 65 and women ≥ 75; when RR is set as 0.9, men ≥ 75 only.

Conclusions

In case of RR of 0.5 and 0.6, the gastric cancer screening are recommended for men ≥ 55 and women ≥ 65 until 2035, while it is not recommended for men and women in the 45–54 even in 2010 and 2015.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Cancer screening, Guidelines

Introduction

In Japan, incidence of gastric cancer is expected to follow the current downward trend as the younger generation has lower incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection [1]. In this study, therefore, we aimed to estimate how long gastric cancer screening is deemed necessary in the future from epidemiologic and statistical perspectives. Of note, for clarification purposes, population-based screening was selected as a screening mode to be analyzed in this study.

In Japan, based on the “Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening 2014 edition” edited by the National Cancer Center [2], the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare recommends radiographic screening and endoscopy as population-based screening [3]. Especially, endoscopy screening was recommended very recently since 2016. In principle, population-based screening should be introduced and conducted after comparing and weighing the benefits regarding mortality reduction and harms concerning screening [4, 5]. Even though there are many disagreements over whether performing screenings falling short of such standard is justifiable, few may take a critical attitude toward conducting screenings if they meet this standard. The challenge here is how to compare the benefits, i.e., size of mortality reduction, to the potential harms of screening. The most common harms associated with screening include false-negative test results, false-positive test results, overdiagnosis, as well as adverse reactions to screening and diagnostic examination procedures. It is not easy to compare these issues with the size of mortality reduction effect because they have fundamentally different natures. In the Japanese guidelines for cancer screening 2014 edition, for comparison between benefits and harms of screening, Number Needed to Screen (NNS), representing the size of mortality reduction effect, is used as a benefit indicator, while recall rate is employed as a risk indicator, which is the same as the Japanese guidelines for breast cancer screening [6]. NNS is an estimated number of people required to participate in a screening program to prevent one death over a defined time interval, and thus the smaller NNS implies larger benefits. On the other hand, recall rate is the number of people required to undergo diagnostic examination procedures to prevent one death over a defined time interval, referred as number needed to recall (NNR) in this article, and the larger NNR implies larger harms, i.e., causing inconvenience to more people. In the above-mentioned Guidelines, the thresholds of 1000 and 100 are set as tentative criteria for NNS and NNR, respectively. To judge the length to continue gastric cancer screening, these criteria were used in the present study due to the following facts: these numbers have been employed in the Guidelines in widespread use; using them can allow qualitative analyses; and there are no alternative proven criteria available. In short, we calculate NNS and NNR, compare them to their corresponding threshold of 1000 and 100, and use the comparison results as a part of a basis for deciding whether it is justifiable to continue or discontinue the gastric cancer screening programs.

To maximize the effect of population-based screening, higher participation rate is necessary. Nevertheless, participation rate is as low as 40% in Japan [7] and the government set the goal as 50% in the Third term Basic Plan to Promote Cancer Control Programs in Japan [8]. Since the number of life saved (NLS) varies according to the participation rate, NLS of participation rate 50% and 100% compared to that of NLS of present rate (40%) are also used as a benefit indicator in this study.

Methods

NNS, NNR, and NLS are estimated by sex and age group. Estimations of NNS, NNR, and NLS require data on gastric cancer mortality, screening effect on mortality reduction, and recall rate. The projections of future gastric cancer deaths by sex and age group in Japan are available from the National Cancer Center [9]. While people are divided into the 7 age groups as follows: 0–14, 15–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, older than or equal to 75 years of age, and all ages, we selected age groups at the time of screening as follows: 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and older than or equal to 75 years of age in our study. In addition to the number of deaths, estimations of mortality rates require estimates of future population, which should be calculated using the same method and numbers used for calculation of the number of deaths, and thus, we used the method described in the reference [10]. However, since there is no publicly disclosed prediction for the future Japanese population in the period of 2015 and beyond, a ratio of Japanese population to the total population in Japan by sex and 5-year age groups were calculated, which in turn was multiplied by the total population estimates (estimated median numbers of births and deaths) for the year of 2020, 2025, 2030, and 2035, to obtain estimates of future Japanese population by sex and 5-year age groups. These data on the Japanese total population are published by The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research [11]. The projections of the gastric cancer mortality rates are estimated for 2020, 2025, 2030, and 2035 using future number of deaths estimates of 2020–2024, 2025–2029, 2030–2034, and 2035–2039, respectively. Mortality trends are shown using observed value until 2015 [12] and estimates for 2020–2035.

To estimate NNS, the above-mentioned Guidelines used relative risks (RR) of gastric cancer mortality reduction for effectiveness of radiography test and endoscopy test from several studies [13–15]. In this study, several relative risk values associated with screening are used for estimation of future NNSs and NNRs in different scenarios. For reference, Table 1 lists the relative risk values used in the Guidelines. These relative risk values ranged from 0.1 to 1.07, which included those either too large or too small to exert any effects, and thus 5 values (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9) were selected to be used in the scenarios in this study. Recently Korean study reported that the effectiveness of endoscopy screening is RR of 0.53 (95% CI 0.51–0.56), which is not contradict from our scenarios [16].

Table 1.

Relative risk used to estimate number needed to screen in the Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer

| Screening | Study | Sex | Age-specific relative risk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | |||

| Radiography | Abe et al. [13] | Male | 0.105 | 0.105 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.271 | 0.271 | 0.429 | 0.429 |

| Female | 0.778 | 0.778 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.385 | 0.385 | 0.882 | 0.882 | ||

| Fukao et al. [14] | Male | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |||

| Female | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.63 | ||||

| Hamashima et al. [15] | Male | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | |

| Female | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.865 | ||

| Endoscopy | Hamashima et al. [15] | Male | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 |

| Female | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.695 | ||

Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2014 edition. http://canscreen.ncc.go.jp/

Recall rates cited in the above-mentioned Guidelines are radiography test data derived from the annual report 2011 of The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening [17], and endoscopy data collected in Niigata City reported in 2012 [18] (Table 2). The ranges of recall rates for radiography test and endoscopy were reported as 4.1–12.2% and 2.9–11.6%, respectively. In this study, we used relative risks of 5% and 10% as scenarios.

Table 2.

Recall rate used to estimate number needed to recall in the Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer

| Screening | Study | Sex | Age-specific recall rate (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | |||

| Radiography | JSGCS [17] | Male | 4.8 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.2 |

| Female | 4.1 | 4.72 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | ||

| Endoscopy | Niigata City [18] | Male | 2.9 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 9.7 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 11.2 |

| Female | 5.8 | 5.4 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | ||

Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2014 edition. http://canscreen.ncc.go.jp/

For estimating NLS, hypothetical number of gastric cancer deaths without screening, D0s, is estimated as follows:

where Dobs is observed number of deaths and Pobs is observed participation rate of screening. NLSt is estimated as a function of target participation rate Pt:

The observed participation rate is set as 40% and target participation rates are set as 50% and 100%. For the future predication, Pobs is assumed as the same as the present participation rate, i.e., 40%.

Results

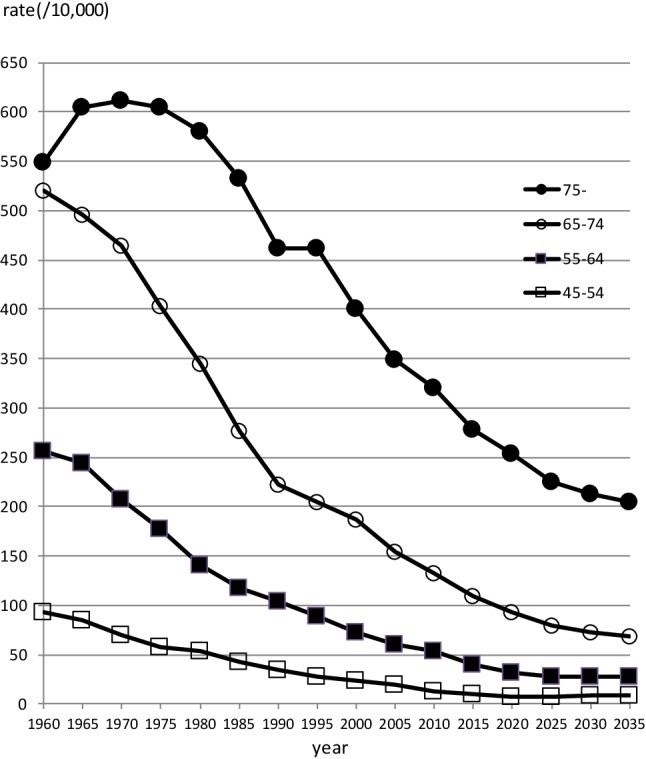

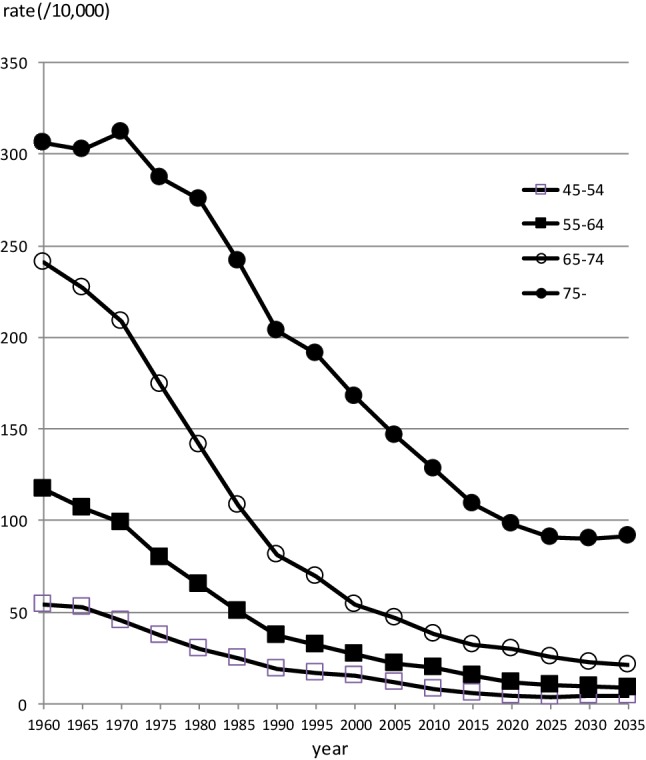

Figures 1 and 2 show past transition and future projections of gastric cancer mortalities by age groups. Downward trends are obvious for both men and women in every age group equal to and older than 45 years old.

Fig. 1.

Observed and projected trends of age-specific gastric cancer mortality in Japan for male

Fig. 2.

Observed and projected trends of age-specific gastric cancer mortality in Japan for female

Tables 3 and 4 show estimates of NNS and NNR. It might be obvious, but higher relative risks (small effect) and/or lower mortality rates make NNS higher. The results indicated that the benefits of the screening exceeded harms more prominently in men than women, older than younger age groups, and now than future. The criteria of both NNS and NNR would be fulfilled, that is, the both benefits and harms are considered within acceptable limits to justify the screening, for the following age groups (year-old): when relative risk (RR) of screening is set as 0.5, men ≥ 55 and women ≥ 65; when RR is set as 0.6, men ≥ 55 and women ≥ 65; when RR is set as 0.7, men ≥ 65 and women ≥ 75; and when RR is set as 0.8, men ≥ 65 and women ≥ 75; when RR is set as 0.9, men ≥ 75 only.

Table 3.

Number needed to screen, number needed to recall, and number of life saved by gastric cancer screening based on future prediction of gastric cancer mortality

| Mortality reductiona | Year | Age 45–54 | Age 55–64 | Age 65–74 | Age 75- | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality rate for 10 yearsb (%) | NNSc | NNRd | NLS5 | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | ||||||||||

| Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | ||||||||||

| RRd = 0.5 | 2010 | 0.13 | 1560 | 78 | 156 | 63 | 376 | 0.54 | 372 | 19 | 37 | 310 | 1861 | 1.32 | 151 | 8 | 15 | 593 | 3559 | 3.21 | 62 | 3 | 6 | 1071 | 6428 |

| 2015 | 0.09 | 2140 | 107 | 214 | 49 | 293 | 0.40 | 497 | 25 | 50 | 199 | 1197 | 1.09 | 184 | 9 | 18 | 565 | 3393 | 2.79 | 72 | 4 | 7 | 1095 | 6572 | |

| 2020 | 0.07 | 2709 | 135 | 271 | 43 | 255 | 0.31 | 643 | 32 | 64 | 147 | 881 | 0.93 | 214 | 11 | 21 | 486 | 2914 | 2.54 | 79 | 4 | 8 | 1165 | 6990 | |

| 2025 | 0.10 | 2725 | 136 | 273 | 41 | 248 | 0.33 | 706 | 35 | 71 | 143 | 855 | 0.89 | 252 | 13 | 25 | 354 | 2126 | 2.55 | 89 | 4 | 9 | 1229 | 7376 | |

| 2030 | 0.08 | 2503 | 125 | 250 | 39 | 233 | 0.28 | 725 | 36 | 73 | 153 | 919 | 0.72 | 278 | 14 | 28 | 308 | 1849 | 2.13 | 94 | 5 | 9 | 1224 | 7346 | |

| 2035 | 0.09 | 2210 | 110 | 221 | 39 | 233 | 0.27 | 732 | 37 | 73 | 148 | 889 | 0.69 | 290 | 14 | 29 | 317 | 1901 | 2.04 | 98 | 5 | 10 | 1148 | 6885 | |

| RR = 0.6 | 2010 | 0.13 | 1950 | 97 | 195 | 48 | 287 | 0.54 | 465 | 23 | 47 | 236 | 1418 | 1.32 | 189 | 9 | 19 | 452 | 2711 | 3.21 | 78 | 4 | 8 | 816 | 4897 |

| 2015 | 0.09 | 2675 | 134 | 268 | 37 | 223 | 0.40 | 621 | 31 | 62 | 152 | 912 | 1.09 | 230 | 11 | 23 | 431 | 2585 | 2.79 | 90 | 4 | 9 | 835 | 5007 | |

| 2020 | 0.07 | 3386 | 169 | 339 | 32 | 194 | 0.31 | 804 | 40 | 80 | 112 | 671 | 0.93 | 268 | 13 | 27 | 370 | 2220 | 2.54 | 98 | 5 | 10 | 888 | 5326 | |

| 2025 | 0.10 | 3407 | 170 | 341 | 31 | 189 | 0.33 | 882 | 44 | 88 | 109 | 651 | 0.89 | 315 | 16 | 32 | 270 | 1620 | 2.55 | 111 | 6 | 11 | 937 | 5620 | |

| 2030 | 0.08 | 3129 | 156 | 313 | 30 | 177 | 0.28 | 906 | 45 | 91 | 117 | 700 | 0.72 | 348 | 17 | 35 | 235 | 1409 | 2.13 | 117 | 6 | 12 | 933 | 5597 | |

| 2035 | 0.09 | 2762 | 138 | 276 | 30 | 177 | 0.27 | 915 | 46 | 92 | 113 | 677 | 0.69 | 362 | 18 | 36 | 241 | 1449 | 2.04 | 123 | 6 | 12 | 874 | 5246 | |

| RR = 0.7 | 2010 | 0.13 | 2600 | 130 | 260 | 34 | 205 | 0.54 | 620 | 31 | 62 | 169 | 1015 | 1.32 | 252 | 13 | 25 | 324 | 1941 | 3.21 | 104 | 5 | 10 | 584 | 3506 |

| 2015 | 0.09 | 3567 | 178 | 357 | 27 | 160 | 0.40 | 829 | 41 | 83 | 109 | 653 | 1.09 | 306 | 15 | 31 | 308 | 1851 | 2.79 | 120 | 6 | 12 | 597 | 3585 | |

| 2020 | 0.07 | 4515 | 226 | 452 | 23 | 139 | 0.31 | 1072 | 54 | 107 | 80 | 481 | 0.93 | 357 | 18 | 36 | 265 | 1589 | 2.54 | 131 | 7 | 13 | 635 | 3813 | |

| 2025 | 0.10 | 4542 | 227 | 454 | 23 | 135 | 0.33 | 1176 | 59 | 118 | 78 | 466 | 0.89 | 420 | 21 | 42 | 193 | 1160 | 2.55 | 148 | 7 | 15 | 671 | 4023 | |

| 2030 | 0.08 | 4171 | 209 | 417 | 21 | 127 | 0.28 | 1208 | 60 | 121 | 84 | 501 | 0.72 | 463 | 23 | 46 | 168 | 1008 | 2.13 | 156 | 8 | 16 | 668 | 4007 | |

| 2035 | 0.09 | 3683 | 184 | 368 | 21 | 127 | 0.27 | 1220 | 61 | 122 | 81 | 485 | 0.69 | 483 | 24 | 48 | 173 | 1037 | 2.04 | 163 | 8 | 16 | 626 | 3755 | |

| RR = 0.8 | 2010 | 0.13 | 3900 | 195 | 390 | 22 | 131 | 0.54 | 930 | 47 | 93 | 108 | 647 | 1.32 | 378 | 19 | 38 | 206 | 1238 | 3.21 | 156 | 8 | 16 | 373 | 2236 |

| 2015 | 0.09 | 5351 | 268 | 535 | 17 | 102 | 0.40 | 1243 | 62 | 124 | 69 | 416 | 1.09 | 459 | 23 | 46 | 197 | 1180 | 2.79 | 179 | 9 | 18 | 381 | 2286 | |

| 2020 | 0.07 | 6773 | 339 | 677 | 15 | 89 | 0.31 | 1608 | 80 | 161 | 51 | 307 | 0.93 | 535 | 27 | 54 | 169 | 1013 | 2.54 | 197 | 10 | 20 | 405 | 2431 | |

| 2025 | 0.10 | 6814 | 341 | 681 | 14 | 86 | 0.33 | 1765 | 88 | 176 | 50 | 297 | 0.89 | 630 | 32 | 63 | 123 | 740 | 2.55 | 222 | 11 | 22 | 428 | 2566 | |

| 2030 | 0.08 | 6257 | 313 | 626 | 13 | 81 | 0.28 | 1813 | 91 | 181 | 53 | 320 | 0.72 | 695 | 35 | 70 | 107 | 643 | 2.13 | 234 | 12 | 23 | 426 | 2555 | |

| 2035 | 0.09 | 5525 | 276 | 552 | 13 | 81 | 0.27 | 1830 | 92 | 183 | 52 | 309 | 0.69 | 724 | 36 | 72 | 110 | 661 | 2.04 | 245 | 12 | 25 | 399 | 2395 | |

| RR = 0.9 | 2010 | 0.13 | 7799 | 390 | 780 | 10 | 63 | 0.54 | 1860 | 93 | 186 | 52 | 310 | 1.32 | 755 | 38 | 76 | 99 | 593 | 3.21 | 312 | 16 | 31 | 179 | 1071 |

| 2015 | 0.09 | 10702 | 535 | 1070 | 8 | 49 | 0.40 | 2486 | 124 | 249 | 33 | 199 | 1.09 | 918 | 46 | 92 | 94 | 565 | 2.79 | 359 | 18 | 36 | 183 | 1095 | |

| 2020 | 0.07 | 13546 | 677 | 1355 | 7 | 43 | 0.31 | 3215 | 161 | 322 | 24 | 147 | 0.93 | 1071 | 54 | 107 | 81 | 486 | 2.54 | 394 | 20 | 39 | 194 | 1165 | |

| 2025 | 0.10 | 13627 | 681 | 1363 | 7 | 41 | 0.33 | 3529 | 176 | 353 | 24 | 143 | 0.89 | 1261 | 63 | 126 | 59 | 354 | 2.55 | 444 | 22 | 44 | 205 | 1229 | |

| 2030 | 0.08 | 12514 | 626 | 1251 | 6 | 39 | 0.28 | 3625 | 181 | 363 | 26 | 153 | 0.72 | 1390 | 70 | 139 | 51 | 308 | 2.13 | 469 | 23 | 47 | 204 | 1224 | |

| 2035 | 0.09 | 11050 | 552 | 1105 | 6 | 39 | 0.27 | 3661 | 183 | 366 | 25 | 148 | 0.69 | 1448 | 72 | 145 | 53 | 317 | 2.04 | 490 | 25 | 49 | 191 | 1148 | |

aRelative risk for mortality reduction by screening

bGastric cancer mortality rate fro 10 years

cNumber needed to screen

dNumber needed to recall

eNumber of life saved

Table 4.

Number needed to screen, number needed to recall, and number of life saved by gastric cancer screening based on future prediction of gastric cancer mortality

| Mortality reductiona | Year | Age 45–54 | Age 55–64 | Age 65–74 | Age 75- | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality rate for 10 yearsb (%) | NNSc | NNRd | NLSe | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | Mortality rate for 10 years (%) | NNS | NNR | NLS | ||||||||||

| Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | Recall rate | Participation rate | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | 5% | 10% | 50% | 100% | ||||||||||

| RR = 0.5 | 2010 | 0.08 | 2497 | 125 | 250 | 39 | 233 | 0.20 | 1019 | 51 | 102 | 116 | 698 | 0.38 | 525 | 26 | 53 | 192 | 1149 | 1.28 | 156 | 8 | 16 | 706 | 4236 |

| 2015 | 0.06 | 3339 | 167 | 334 | 31 | 184 | 0.15 | 1304 | 65 | 130 | 77 | 465 | 0.32 | 617 | 31 | 62 | 186 | 1113 | 1.09 | 183 | 9 | 18 | 680 | 4081 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 4893 | 245 | 489 | 23 | 139 | 0.12 | 1722 | 86 | 172 | 56 | 334 | 0.30 | 675 | 34 | 68 | 168 | 1009 | 0.98 | 204 | 10 | 20 | 694 | 4166 | |

| 2025 | 0.04 | 5198 | 260 | 520 | 21 | 128 | 0.10 | 1980 | 99 | 198 | 51 | 308 | 0.25 | 792 | 40 | 79 | 123 | 735 | 0.91 | 221 | 11 | 22 | 736 | 4418 | |

| 2030 | 0.04 | 5090 | 255 | 509 | 19 | 113 | 0.09 | 2124 | 106 | 212 | 53 | 315 | 0.23 | 887 | 44 | 89 | 104 | 623 | 0.90 | 222 | 11 | 22 | 768 | 4609 | |

| 2035 | 0.04 | 4791 | 240 | 479 | 18 | 105 | 0.09 | 2234 | 112 | 223 | 49 | 293 | 0.21 | 959 | 48 | 96 | 102 | 611 | 0.92 | 218 | 11 | 22 | 775 | 4650 | |

| RR = 0.6 | 2010 | 0.08 | 3121 | 156 | 312 | 30 | 177 | 0.20 | 1273 | 64 | 127 | 89 | 532 | 0.38 | 656 | 33 | 66 | 146 | 876 | 1.28 | 195 | 10 | 19 | 538 | 3227 |

| 2015 | 0.06 | 4174 | 209 | 417 | 23 | 140 | 0.15 | 1630 | 82 | 163 | 59 | 354 | 0.32 | 771 | 39 | 77 | 141 | 848 | 1.09 | 229 | 11 | 23 | 518 | 3109 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 6117 | 306 | 612 | 18 | 106 | 0.12 | 2153 | 108 | 215 | 42 | 254 | 0.30 | 844 | 42 | 84 | 128 | 769 | 0.98 | 255 | 13 | 25 | 529 | 3174 | |

| 2025 | 0.04 | 6497 | 325 | 650 | 16 | 97 | 0.10 | 2475 | 124 | 247 | 39 | 234 | 0.25 | 990 | 50 | 99 | 93 | 560 | 0.91 | 276 | 14 | 28 | 561 | 3366 | |

| 2030 | 0.04 | 6363 | 318 | 636 | 14 | 86 | 0.09 | 2655 | 133 | 266 | 40 | 240 | 0.23 | 1109 | 55 | 111 | 79 | 474 | 0.90 | 277 | 14 | 28 | 585 | 3511 | |

| 2035 | 0.04 | 5989 | 299 | 599 | 13 | 80 | 0.09 | 2792 | 140 | 279 | 37 | 223 | 0.21 | 1199 | 60 | 120 | 78 | 466 | 0.92 | 273 | 14 | 27 | 590 | 3543 | |

| RR = 0.7 | 2010 | 0.08 | 4161 | 208 | 416 | 21 | 127 | 0.20 | 1698 | 85 | 170 | 63 | 381 | 0.38 | 875 | 44 | 88 | 104 | 627 | 1.28 | 260 | 13 | 26 | 385 | 2311 |

| 2015 | 0.06 | 5565 | 278 | 557 | 17 | 100 | 0.15 | 2173 | 109 | 217 | 42 | 253 | 0.32 | 1028 | 51 | 103 | 101 | 607 | 1.09 | 306 | 15 | 31 | 371 | 2226 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 8156 | 408 | 816 | 13 | 76 | 0.12 | 2870 | 144 | 287 | 30 | 182 | 0.30 | 1125 | 56 | 113 | 92 | 550 | 0.98 | 339 | 17 | 34 | 379 | 2273 | |

| 2025 | 0.04 | 8663 | 433 | 866 | 12 | 70 | 0.10 | 3300 | 165 | 330 | 28 | 168 | 0.25 | 1320 | 59 | 132 | 67 | 401 | 0.91 | 368 | 18 | 37 | 402 | 2410 | |

| 2030 | 0.04 | 8484 | 424 | 848 | 10 | 61 | 0.09 | 3541 | 177 | 354 | 29 | 172 | 0.23 | 1478 | 74 | 148 | 57 | 340 | 0.90 | 370 | 18 | 37 | 419 | 2514 | |

| 2035 | 0.04 | 7985 | 399 | 799 | 10 | 57 | 0.09 | 3723 | 186 | 372 | 27 | 160 | 0.21 | 1599 | 80 | 160 | 56 | 333 | 0.92 | 363 | 18 | 36 | 423 | 2536 | |

| RR = 0.8 | 2010 | 0.08 | 6241 | 312 | 624 | 14 | 81 | 0.20 | 2546 | 127 | 255 | 40 | 243 | 0.38 | 1313 | 66 | 131 | 67 | 400 | 1.28 | 390 | 19 | 39 | 246 | 1473 |

| 2015 | 0.06 | 8348 | 417 | 835 | 11 | 64 | 0.15 | 3260 | 163 | 326 | 27 | 162 | 0.32 | 1542 | 77 | 154 | 65 | 387 | 1.09 | 459 | 23 | 46 | 237 | 1420 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 12234 | 612 | 1223 | 8 | 48 | 0.12 | 4306 | 215 | 431 | 19 | 116 | 0.30 | 1688 | 84 | 169 | 58 | 351 | 0.98 | 509 | 25 | 51 | 242 | 1449 | |

| 2025 | 0.04 | 12994 | 650 | 1299 | 7 | 44 | 0.10 | 4949 | 247 | 495 | 18 | 107 | 0.25 | 1980 | 99 | 198 | 43 | 256 | 0.91 | 551 | 28 | 55 | 256 | 1537 | |

| 2030 | 0.04 | 12726 | 636 | 1273 | 7 | 39 | 0.09 | 5311 | 266 | 531 | 18 | 110 | 0.23 | 2218 | 111 | 222 | 36 | 217 | 0.90 | 554 | 28 | 55 | 267 | 1603 | |

| 2035 | 0.04 | 11978 | 599 | 1198 | 6 | 37 | 0.09 | 5584 | 279 | 558 | 17 | 102 | 0.21 | 2398 | 120 | 240 | 35 | 213 | 0.92 | 545 | 27 | 55 | 270 | 1617 | |

| RR = 0.9 | 2010 | 0.08 | 12483 | 624 | 1248 | 6 | 39 | 0.20 | 5093 | 255 | 509 | 19 | 116 | 0.38 | 2626 | 131 | 263 | 32 | 192 | 1.28 | 779 | 39 | 78 | 118 | 706 |

| 2015 | 0.06 | 16695 | 835 | 1670 | 5 | 31 | 0.15 | 6520 | 326 | 652 | 13 | 77 | 0.32 | 3083 | 154 | 308 | 31 | 186 | 1.09 | 917 | 46 | 92 | 113 | 680 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 24467 | 1223 | 2447 | 4 | 23 | 0.12 | 8611 | 431 | 861 | 9 | 56 | 0.30 | 3376 | 169 | 338 | 28 | 168 | 0.98 | 1018 | 51 | 102 | 116 | 694 | |

| 2025 | 0.04 | 25988 | 1299 | 2599 | 4 | 21 | 0.10 | 9899 | 495 | 990 | 9 | 51 | 0.25 | 3960 | 198 | 396 | 20 | 123 | 0.91 | 1103 | 55 | 110 | 123 | 736 | |

| 2030 | 0.04 | 25452 | 1273 | 2545 | 3 | 19 | 0.09 | 10622 | 531 | 1062 | 9 | 53 | 0.23 | 4435 | 222 | 444 | 17 | 104 | 0.90 | 1109 | 55 | 111 | 128 | 768 | |

| 2035 | 0.04 | 23955 | 1198 | 2396 | 3 | 18 | 0.09 | 11169 | 558 | 1117 | 8 | 49 | 0.21 | 4796 | 240 | 480 | 17 | 102 | 0.92 | 1090 | 55 | 109 | 129 | 775 | |

aRelative risk for mortality reduction by screening

bGastric cancer mortality rate fro 10 years

cNumber needed to screen

dNumber needed to recall

eNumber of life saved

NLS, which is a function of RR, mortality, and participation rate, is substantial for age 65 or older when participation rate is 50% as a national goal while it is not so large for either two combination of female, RR ≥ 0.8, and age 54 or younger.

Discussion

In this study, target population and length appropriate to continue gastric cancer screening were investigated based on the future projection of gastric cancer mortality, from the standpoint of balancing the benefits and harms of the screening. As a result, until 2035, screening programs with higher mortality reduction effects (relative risk 0.5 and 0.6) are shown to be beneficial for men ≥ age 55 and women ≥ age 65. It is expected that, under conditions and scenarios selected in this study, both men and women in the 45–54 age group did not meet the criteria for benefits and harms even in 2010 and 2015.

This study can provide evidence for the decision based on benefits and harms by numerical criteria using NNS, NNR, and NSL. In this way, balancing estimates of benefits and harms is a standard method to evaluate whether to introduce and continue population-based screening [5, 19, 20]. While more comprehensive balance sheets have been proposed [21, 22], typical indicators are those for concerning mortality reduction for benefit and false-positive, overdiagnosis, and adverse reactions to screening and diagnostic examination procedures for harm [19, 20, 23]. The NNS and NNR used in this study are transformed indictors of mortality reduction and false-positive for intuitive interpretation. Overdiagnosis indicators cannot be examined due to lack of reports about overdiagnosis for gastric cancer screening [2]. Because of the difficulty of comparing severity of adverse reactions with screening benefit in numerical way, NNS and NNR were used to balance benefits and harms in this study. As for the threshold, no consensus was obtained due to the uncertainty and variability in the evidence used to make these estimates [20] or a matter of individual judgement [19]. In this study, we used threshold of 1000 for NNS and 100 for NNR based on the Japanese guidelines for cancer screening 2014 edition [2]. These threshold has some sense in Japan because the recommendation of the guideline and following government decision was made based on this value. Even in case of not using such threshold, combination of NNS and NNR for various scenarios in Tables 3 and 4 will help to evaluate whether to continue gastric cancer screening.

There are several limitations in this study. NNSs, NNRs, and NLS addressed in this study are limited to those estimated using the data obtained for both male and female in the age groups of 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and equal to and older than 75 years, projected for 2020, 2025, 2030, and 2035, due to limited availability of the relevant data. The accurate data of the effect size of screening on mortality, recall rate, and participation rate are not available in Japan, while the detailed and accurate data on mortality rates and their projections were available. Unfortunately, however, although stomach cancer screening has been recommended for age 40 or older until 2015 and is recommended for age 50 or older since 2016, the projections are only available for age groups of 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and equal to and older than 75 years old. Although NNSs, NNRs, and NLSs outside of these scenarios cannot be estimated due to data availability, they can be speculated by intrapolation of the values of mortality rate, relative risk, and recall rate within the scenarios. Owing to the simple relationships among these values, the results can be speculated that gastric cancer screening is not recommended for men and women with age 50 based on the threshold of NNS < 1000 and NNR > 100 for all the scenarios (Tables 3, 4). As a matter of course, in real situations, other benefits and harms of the screening should be considered such as less invasive treatment due to early detection as benefits and adverse reactions of the screening and diagnostic examinations as harms.

Considering the criteria of benefits and harms as NNS < 1000 and NNR > 100, respectively, these estimates may imply that, compared to sex, age and screening effect, the trend toward mortality reduction may have less impact on NNS and NNR, at least until 2035. Recall rates are closely related to prevalence, sensitivity, specificity, and screening effect, and therefore, it is important to manage the accuracy level of screening to maintain the recall rates in reasonable range. Furthermore, NLS heavily depends on participation rate of screening, it is most important to increase participation rate as high as possible.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Developmental Fund (29-A-20).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical consideration

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Hiroi S, Sugano K, Tanaka S, Kawakami K. Impact of health insurance coverage for Helicobacter pylori gastritis on the trends in eradication therapy in Japan: retrospective observational study and simulation study based on real-world data. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015855. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Cancer Center. Japanese guidelines for cancer screening 2014 edition. http://canscreen.ncc.go.jp/. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 3.Ministry of Health, Labour, Welfare of Japan. Gan-kenshin. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000059490.html. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 4.Hamashima C, Saito H, Nakayama T, Nakayama T, Sobue T. The standardized development method of the Japanese guidelines for cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(4):288–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hamashima C. Cancer screening guidelines and policy making: 15 years of experience in cancer screening guideline development in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(3):278–286. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamashima C, Japanese Research Group for the Development of Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines The Japanese guidelines for breast cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(5):482–492. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Labour. Welfare of Japan. Comprehensive survey of living conditions 2016. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa16/index.html. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 8.Ministry of Health, Labour. Welfare of Japan. The third term basic plan for cancer control. 2018. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000183313.html. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 9.Cancer Registry and Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. Projection of future incidence, death, prevalence of cancer in Japan (2015–2039). https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 10.Saika K, Matsuda T, Sobue T. Projection of future cancer deaths in Japan. In: Sobue T, editor. Gan-Tokei Hakusho 2012. Tokyo: Shinoharashinsha Publishers; 2012. pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Projection of future population of Japan. 2017 estimates. http://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/j/zenkoku2017/pp_zenkoku2017.asp. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 12.Cancer Registry and Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. Cancer mortality data from vital statistics of Japan (1958–2016). https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 13.Abe Y, Mitsushima T, Nagatani K, Ikuma H, Minamihara Y. Epidemiological evaluation of the protective effect for dying of stomach cancer by screening programme for stomach cancer with applying a method of case-control study—a study of a efficient screening programme for stomach cancer. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;92(5):836–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukao A, Tsubono Y, Tsuji I, et al. The evaluation of screening for gastric cancer in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(1):45–48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamashima C, Ogoshi K, Okamoto M, et al. A community-based, case–control study evaluating mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening in Japan. PLosS One. 2013;8(11):e79088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Suh M, Park B, Song SH, Jung KW, Lee CW, Choi IJ, Park EC, Lee D. Effectiveness of the Korean national cancer screening program in reducing gastric cancer mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1319–1328. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening. Annual Report 2011. The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening, 2011.

- 18.Niigata Medical Association. 10-year History of Niigata city endoscopy screening. PP.81–4. 2012.

- 19.Paci E, EUROSCREEN Working Group Summary of the evidence of breast cancer service screening outcomes in Europe and first estimate of the benefit and harm balance sheet. J Med Screen. 2012;19(Suppl 1):5–13. doi: 10.1258/jms.2012.012077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Procedure Manual. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/procedure-manual. Accessed 5 June 2018.

- 21.Austoker J. Cancer prevention: Setting the scene. BMJ. 1994;308:1415–1420. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6941.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Maas PJ, de Koning HJ, van Ineveld BM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 1989;15(6):1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris R, Sawaya GF, Moyer VA, Calonge N. Reconsidering the criteria for evaluating proposed screening programs: reflections from 4 current and former members of the US preventive services task force. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:20–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]