Abstract

Pollination is a key ecological process, and invasive alien plant species have been shown to significantly affect plant-pollinator interactions. Yet, the role of the environmental context in modulating such processes is understudied. As urbanisation is a major component of global change, being associated with a range of stressors (e.g. heat, pollution, habitat isolation), we tested whether the attractiveness of a common invasive alien plant (Robinia pseudoacacia, black locust) vs. a common native plant (Cytisus scoparius, common broom) for pollinators changes with increasing urbanisation. We exposed blossoms of both species along an urbanisation gradient and quantified different types of pollinator interaction with the flowers. Both species attracted a broad range of pollinators, with significantly more visits for R. pseudoacacia, but without significant differences in numbers of insects that immediately accessed the flowers. However, compared to native Cytisus, more pollinators only hovered in front of flowers of invasive Robinia without visiting those subsequently. The decision rate to enter flowers of the invasive species decreased with increasing urbanisation. This suggests that while invasive Robinia still attracts many pollinators in urban settings attractiveness may decrease with increasing urban stressors. Results indicated future directions to deconstruct the role of different stressors in modulating plant-pollinator interactions, and they have implications for urban development since Robinia can be still considered as a “pollinator-friendly” tree for certain urban settings.

Subject terms: Invasive species, Urban ecology

Introduction

Invasive alien plant species have been reported to be a major driver of change in altering biodiversity patterns1–3. By contrast, a recent meta-analysis reveals largely reducing or neutral effects of invasive plants on animal abundance, diversity, fitness, and ecosystem processes4. Responses of native insects to invasive plants are mostly ambiguous5, and include negative6,7 as well as positive effects8,9. By modulating plant-pollinator networks10–12, invasive plants can also affect key ecological processes with a high relevance for plant reproduction and thus for agriculture, food production and food security13–15, even in urban environments16,17.

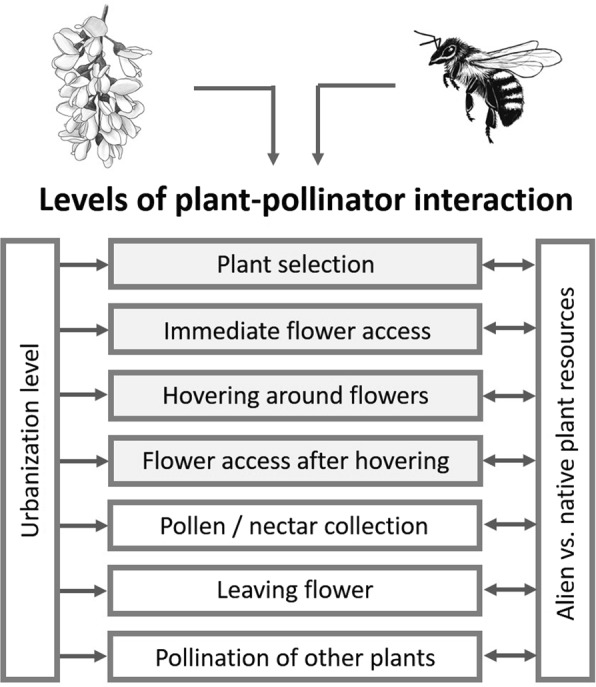

Plant-pollinator interactions comprise several interlinked processes that result in different levels (Fig. 1)18,19. The first is, from the pollinator perspective, the selection of a plant as a floral resource, followed by access to the flower, either immediately or after a period of hovering around the florescence (Fig. 1). After accessing the flower, pollen or nectar can then be collected and carried to its nest or another plant.

Figure 1.

Generalised sequence of plant-pollinator interaction in relation to decisions between using native vs. alien plant resources and potential interactions with different levels of urbanisation. Levels in filled boxes were addressed in this study.

Previous studies showed that alien plant species can significantly modulate important components within plant-pollinator interactions and networks20–22. For example, plant selection and blossom access can differ between invasive and native plants19,23–25, with multidirectional patterns as pollinators preferring either native or invasive plants18, or in some cases neither26. Studies on pollen and nectar collection found that food resources of invasive plants can be either neglected by native pollinators27,28 or accepted as new foraging alternatives29,30. Due to competition for pollinators, the presence of invasive plants can affect flower visits10,31 and the pollination success of native plants, again with different outcomes22,32.

Given the multidirectional effects of invasive plants on plant-pollinator networks18,22,33, understanding the underlying mechanisms is a key challenge. Previous studies revealed a range of mechanisms related, for example, to flower morphology34, nectar chemistry and pollen quality35, spatial scale36, and biological plasticity of pollinating species9.

However, effects of different environmental settings on pollinator interactions have received less attention37. This is an important research question as recent studies increasingly evidence the role of stressors related to climate change38,39, land-use changes40,41 or urbanisation42–44 in modulating plant-pollinator interactions and networks45. Whether varying levels of urbanisation and associated stressors (e.g. heat, pollution, habitat isolation) affect the attractiveness of native vs. alien plants for pollinators could be revealed by applying a standardised study design with pairwise alien/native comparisons. To the best of our knowledge, such studies are missing thus far. This is a vital knowledge gap as cities are hotspots of alien plant species46,47. At the same time, cities have increased in importance as habitats for pollinators48,49 with a conspicuous decline in rural settings50,51. A better understanding of interactions between invasive plants, urbanisation and pollinators will shed light on understudied mechanisms in plant-pollinator networks22 and could support pollinator-friendly urban conservation policies52.

Therefore, we tested whether urbanisation modulated the attractiveness of an invasive vs. a native plant species for pollinators at different interaction levels, as indicated in Fig. 1. In a standardised pair-wise approach, we exposed blossoms of Robinia pseudoacacia L. (black locust; henceforth Robinia) and Cytisus scoparius (L.) (common broom; henceforth Cytisus) to the same type of ecosystem along an urbanisation gradient in Berlin. While the first species is native to North America and has been classified as invasive in Europe53, the latter is native to Europe, but invasive elsewhere54. Both species share biological features that are relevant for pollinators, such as flower morphology and attractive flower colour34. We quantified plant choice and accessing of flowers by native pollinators through direct observation. We differentiated between: (i) immediate blossom access, (ii) hovering around flowers without blossom access, and (iii) blossom access after hovering (Fig. 1). Environmental conditions regarding plant community, flower coverage and maintenance were similar at each study site, except that the location was different in relation to levels of urbanisation (Appendix 1).

We hypothesised that the native and alien plants did not differ in their attractiveness for pollinators since they shared the same flower morphology, flowering time, and both had highly attractive flower colours. We therefore expected no significant differences in plant contact of any type, immediate blossom access, only hovering around flowers, or blossom access after hovering. Since urbanisation and related environmental stressors might affect plant-pollinator interactions, we also hypothesised that the attractiveness of the invasive plant for pollinators will decrease with increasing urbanisation. Extent of green area within the city positively affects plant-pollinator interactions in terms of bee visitation which implies adverse effects due to an increased amount of impervious area43. Mutualisms that have evolved over long evolutionary time scales – as in the case of native plants and native pollinators – might be more resilient to anthropogenic disturbances or stressors than younger ones55–57. We therefore expect that younger mutualisms – for example between native pollinators and alien plants – might have a lower resilience and a more prone to disturbance which in turn should result in reduced interactions such as visitation rates. Consequently, we expected pollinators to select Robinia less frequently with urban than non-urban sites.

Results

General results

A broad range of pollinator taxa visited flowers of both the native and the alien plant species. Pollinators included, with decreasing abundance Diptera s. l. (147), Hymenoptera s. l. (114), bumblebees (24), honey bees (17), and beetles (12), while hoverflies, wild bees, butterflies and wasps played a minor role (Appendix 2).

Attractiveness of Robinia and Cytisus for pollinators

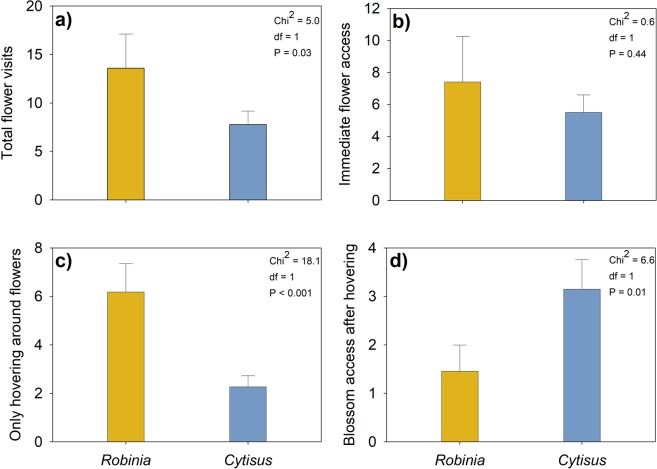

Robinia attracted significantly more pollinators than Cytisus (Chi2 = 5.0, df = 1, P = 0.03; generalised linear mixed model, GLMM; Fig. 2a). However, the number of immediate flower access attempts was the same for both species (Chi2 = 0.6, df = 1, P = 0.44; GLMM; Fig. 2b). In contrast, the number of pollinators that only hovered around a flower without directly contacting it was significantly higher for Robinia than for Cytisus (Chi2 = 18.1, df = 1, P < 0.001; GLMM; Fig. 2c). The decision rate for contact with flowers after hovering was significantly higher for Cytisus compared to Robinia (Chi2 = 6.6, df = 1, P = 0.01; GLMM; Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Total flower visits (=summation of the following categories b, c, and d) differed significantly between the invasive Robinia pseudoacacia and the native Cytisus scoparia (a); while immediate flower access was not significantly different (b). Hovering around flowers was more frequent in the presence of R. pseudoacacia (c); but pollinators decided upon contact with C. scoparia more often after hovering (d; GLMM with Gaussian distribution).

Urbanisation and attractiveness of Robinia

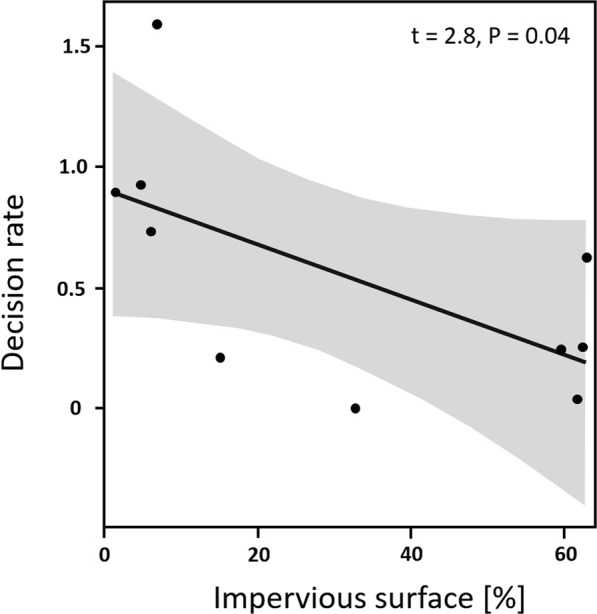

Urbanisation was not correlated with total flower visits, immediate blossom access and hovering around flowers. Yet, we found a significant urbanisation effect on plant-pollinator interactions as the decision to visit flowers of Robinia after hovering decreased with increasing percentage of impervious area around the study site (t = 2.8, P = 0.04; generalised linear model, GLM; Fig. 3). No other environmental variable affected any of the response variables.

Figure 3.

Decision to visit flowers of Robinia pseudoacacia after hovering in front of the florescence significantly decreased with increasing levels of urbanisation (GLMM with Gaussian distribution).

Discussion

Cities are important habitats for pollinators49,58, and previous research has revealed urbanisation effects on the composition of wild bee populations59–63. Moreover, it has been suggested that the high presence of alien plant species in cities46,47 negatively affects native pollinators due to problems of accessibility with novel flower types or because of differences in the quality of nectar or pollen18,35. However, to what extent urbanisation modulates interactions of native pollinators with alien vs. native plants remains a critical knowledge gap37,64. Pollinator observations in urban environments have yielded important insights into plant-pollinator interactions29,43,44,65–68, although these studies did not directly compare native vs. invasive species. This study took a step forward by analysing the interacting effects of biological invasion and urbanisation on plant-pollinator interactions.

Attractiveness of Robinia to native pollinators

Alien plant species have been demonstrated to provide valuable floral resources for pollinators in urban environments30,33, including Robinia in Berlin44 and Paris29 and Cytisus in its non-native North American range69. A previous study found weak negative effects of R. pseudoacacia on urban insect communities70. Yet, Robinia strongly invests in reproductive organs, producing a large flower crop and valuable nectar resource29,71. However, the capacity of an invasive species to provide suitable resources can be different in native and novel landscapes72. While honeybees had been reported as major pollinators53, a recent study reveals a range of wild bee species also visits flowers of urban Robinia trees44. Our study documented that floral resources of Robinia attracted an even broader range of pollinator taxa in urban settings, including wild bees and flies, as well as honey bees (Appendix 2). In addition to the attractiveness of its floral resources, the long presence of Robinia in Europe over a period of >350 years53 might have helped to integrate the alien plant into native pollinator communities, as has been shown in other cases5,73.

Due to its large flower crop, Robinia provided abundant nectar resources which attracted different native pollinators among the Diptera and Hymenoptera. The number of total flower visits was significantly higher for Robinia compared to Cytisus (Fig. 2a), while there was not a significant difference in immediate flower access (Fig. 2b). Acceptance of invasive plants as food resource in the presence of a native alternative has been documented previously for urban habitats29,33,44. However, as a surprising result of our study, more pollinators hovered significantly longer in front of Robinia flowers (Fig. 2c), and significantly less decided to visit the alien flowers after hovering compared to those that hovered in front of native Cytisus flowers (Fig. 2d). Both species were presented in an array that ensured free plant choice and easy access. Given that Robinia and Cytisus shared a similar floral morphology and blossom colours, that are very attractive and easily recognized by pollinators, these results might indicate a trade-off behaviour. This means that pollinators have to make economic choices about what type of flowers they visit to increase benefits (energy intake) compared to costs (energy consumption)74. Due to these energetic requirements nutrient availability in nectar or pollen plays a vital role30,35. Therefore, one reason for lower decision rates for Robinia might be related to quality and suitability of the nectar which might be superior in Cytisus compared to Robinia. Although honey bees successfully process nectar of Robinia75 other non-domesticated and more specialised pollinators could be more sensitive in their nutritional requirements30. In that case, longer hovering in front of Robinia flowers without subsequent flower visits could hint at an ecological trap76, since this behaviour could disrupt the metabolic cost/benefit balance, energy expended for no reward77. However, analysis of Robinia nectar and pollen quality did not support this hypothesis, revealing high contents of suitable amino acids, phytosterol and sugar29. Apart from energetic requirements that affect flower selection, pollinators are faced with other economic choices when choosing a species or not such as risk-sensitivity to predators, mate searching, nest provisioning, distance to nest, floral landscape features and flower handling74. For example, despite obvious similar floral morphology foraging for nectar and pollen on alien Robinia might result in lower load sizes or longer handling times making that species less attractive in harsher environments due to higher costs.

Urbanisation and plant-pollinator interaction

It is well established that urbanisation modulates biodiversity patterns across a range of taxa78,79, including pollinators61,80–82. Our results suggest that biological invasion and urbanisation might jointly affect plant-pollinator interactions. While Robinia did attract a broad range of pollinators in urban settings, similar to an attractive native plant (Appendix 2), decisions of pollinators to visit Robinia flowers after hovering in front of the florescence decreased significantly with increasing levels of urbanisation (Fig. 3), unlike for the native Cytisus (results not shown). This was consistent with Hausmann et al.44, who generally found fewer flower visits at trees (including Robinia) in urban settings; however, they did not differentiate between alien and native species in pairwise comparisons.

Why might increasing urbanisation make a generally highly attractive alien plant species less attractive to pollinators? Urbanisation related stressors, such as heat, pollution and habitat fragmentation38, might combine to produce harsher environmental conditions for pollinators that could translate into changes in biotic interactions83,84, including feeding behaviour and food choice along rural-urban gradients85. For example, urbanisation and related higher amount of impervious area might generally reduce bee visitation rates in cities43. Our study detected some negative effects of urbanization in flower visitation in the invasive plant species, but not in its native counterpart. This might be explained by a shorter time of co-evolution between alien vs. native plants and native pollinators making interactions less resilient against environmental stress - in line with theories of Sachs & Simms55 and Kiers et al.56 on mutualisms in a changing world. These authors assume that mutualisms that have evolved over long time scales are more resilient to anthropogenic impacts compared to more recently established mutualisms. At first appearance, Robinia might be attractive by offering large flower crops which resulted in higher numbers of hovering. Yet a shorter evolutionary experience in using food resources of the alien vs. the native species might translate to lower decision rates to visit the alien plant.

As the community structure of wild bees can change with urbanisation59–62, different pollinators with different food preferences might be present in rural vs. urban settings. Such changes might affect plant-pollinator interactions. However, we assume a low effect of species turnover, since the percentage of more common and less specialised species usually increases with urbanisation59,68,86. In our study, environmental constraints (i.e. heavy rainfalls) reduced the flowering time of Robinia which led to a relatively low number of replications. We addressed that by maximising the observation periods per site to increase the validity of our data.

Our study has implications for future initiatives. While we found a significant relationship between urbanisation and changes in interaction between a native pollinator and a common alien invasive plant, the roles of the different urban stressors were not determined. Unlike many native tree species that might not grow successfully in harsh urban environments87, Robinia is well adapted to such conditions and a warmer climate88. Despite a decreasing attractiveness of Robinia along with increasing urbanisation, this alien tree species still remained attractive for many pollinators. Robinia can thus be considered as a “pollinator-friendly” tree for urban settings – particularly when native alternatives are excluded by harsh urban environments.

Material and Methods

Study area and study system

The study was performed in Berlin, Germany, which has an area of 892 km² and about 3.6 million inhabitants. The climate was temperate, with an annual mean temperature of 9.9 °C and a mean precipitation of 576 mm (reference period: 1981–2010)89. Berlin represented a complex urban matrix with a variety of land uses, consisting of roughly 54% built-up areas, 21% woodland, 12% green space, 6% water, 5% grassland and 2% arable fields90. We used urban grasslands as the study system, as these ecosystems are known as important habitats for wild bees49,61,91 and represent a major component of Berlin’s greenspace system92.

To test for effects of urbanisation on the attractiveness of invasive vs. native species for pollinators, we chose Robinia as a model of an invasive plant as it has abundantly colonized a range of ecosystem types in central Europe, including cities53,93. In Berlin, Robinia was present in a range of habitats across the city, also forming extensive stands78,94.

As different flower symmetry could mask other effects, such as different flower accessibility, and therefore hamper pair-wise comparisons34,95, we chose Cytisus as a native reference species for the comparative plot-design. Cytisus and Robinia were both members of the Fabaceae, and shared similar flower morphology, blooming period, and flower colour (i.e., yellow and white), that usually attracted many pollinators (see Galloni et al.96 for Cytisus). Both species have been present in Berlin over a period of >300 years and have colonized a range of ecosystem types94, sometimes co-habiting vacant land and transition zones between pioneer forests and dry grassland.

Study design

The study was conducted at 10 sites (Appendix 1) that were all located in urban dry grassland, within a minimal distance of 1 km to avoid nestedness. Ten study sites have been demonstrated to be a meaningful sample size for direct pollinator observations44. To assess the effect of urbanisation on pollinator-plant contacts, grassland sites were assigned to different levels of urbanisation. This was determined by the amount of impervious surface, the human population density and the density of roads in a radius of 100 m and 500 m around the sampling site. Correlating these measures with specific sites quantified urbanisation more precisely than using a spatial gradient from an urban core to the outskirts97. Measurements of impervious surface, human population density and density of roads were taken from the Senate Department for Urban Development and Housing98 using a geographic information system (GIS). As all three variables, and both radii, were highly correlated (r > 0.9), we used the amount of impervious surface in a 500 m radius as the urbanisation measure (min = 1.19%, max = 62.78%). To test for potentially confounding effects of vegetation related parameters, we assessed coverage of herbal layer, total and alien plant species richness; the latter parameter included species introduced (neophytes) since 1492. Vegetation data were sampled in vegetation relevés (4 × 4 m), following the standard approach of Braun-Blanquet99.

We applied a standard method for investigating plant-pollinator interactions by exposing vases with flowering branches to potential pollinators18. To reduce wilting, flowering branches of both species were taken from plants from one donor site close to the study sites and immediately placed into water-filled flower vases. Four vases with equal numbers of flowering branches of Robinia and Cytisus (8 vases in total) were alternately placed 90 cm apart from one another in a square, with observers located nearby. After counting pollinators, blossoms per vase were counted to ensure standardisation for statistical analyses.

Data collection

In June 2017, pollinator counts were carried out under good weather conditions100, with clear skies, wind speed at 1–1.4 m/s and warm temperatures (≥22 °C). We measured air temperature, air humidity and wind speed using a hand anemometer (M0198652 Handheld USB Thermo-Hygro-Anemometer). The observations started around noon. While observation periods of 15 minutes have led to reasonable results in a comparable study44, we extended the time to 45 minutes to enhance accuracy of data. We were only able to sample each site once because optimal sampling conditions were limited to 4 days, due to a period of heavy rainfall, and because of rapid wilting of Robinia flowers.

Flower visits were differentiated into 3 categories (Fig. 1): immediate flower access, hovering around flowers with subsequent flower access, and hovering without flower access. Summation of these categories provided the total number of flower visits. Based on flower access after hovering, we also determined a decision rate for visits to a particular species by dividing the number of times flowers were accessed after hovering by the hovering count. During pollinator counting we distinguished optically between the following pollinator taxa: honey bees (Apis mellifera), bumblebees (Bombus spp.), wild bees (Apidae, but not members of the genera Apis and Bombus), wasps (Apocrita), hoverflies (Syrphidae), other flies, mosquitoes (Diptera), beetles (Coleoptera), and butterflies (Lepidoptera). When honey bees and wild bees could not be distinguished correctly both taxa were merged as Hymenoptera s. l. This is a method for assessing pollinator visits to plants that has previously been used101.

Statistical analysis

Prior to analyses, we standardised pollinator counts and calculated contacts or hovering, respectively, per 100 blossoms. To determine the relative attractiveness of Robinia or Cytisus we compared the number of direct contacts, the number of hovering instances and the decision rate using GLMM (R function lmer) taking a Gaussian distribution. Data were log-transformed before and distribution was checked graphically using diagnostic plots102. Location was considered a random effect to meet the requirements for testing paired samples. To test, if attractiveness of the alien vs. native plant for pollinators changed along an urbanisation gradient, we first calculated the ratio for direct contacts, hovering and decision ratio between Robinia and Cytisus. Smaller ratios indicated a higher attractiveness for Robinia blossoms, and vice versa. We analysed effects of urbanisation (% impervious area in a 500 m radius) and vegetation variables (number of plant species and of neophytes) on immediate blossom access, only hovering around flowers, and decision ratios using a GLM with Gaussian distribution. Backward selection of variables was based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) values, where the lowest AIC denoted the best model.

Supplementary information

Appendix 1: Spatial and environmental data at study sites.Appendix 2: Total counts for pollinator taxa interacting with flowering branches of the invasive alien plant Robinia pseudoacacia and the native plant Cytisus scoparius. Diptera s. l. comprised all flies except Syrphidae. Insects were assigned to Hymenoptera s. l. when differentiation between honey bees and wild bees was not possible.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michele Meyer and Niklas Heinemann for pollinator observations, Moritz von der Lippe and Anne Hiller for site data collection. The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research BMBF within the Collaborative Project “Bridging in Biodiversity Science-BIBS” (funding number 01LC1501A-H).

Author Contributions

S.B. designed the study, supervised data collection, analysed output data and performed statistical analyses. I.K. provided materials. S.B. and I.K. took an equal part in writing and revising the manuscript.

Data Availability

The supplementary data is included as an appendix.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42884-6.

References

- 1.Cameron EK, Vila M, Cabeza M. Global meta-analysis of the impacts of terrestrial invertebrate invaders on species, communities and ecosystems. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2016;25:596–606. doi: 10.1111/geb.12436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallardo B, Clavero M, Sanchez MI, Vila M. Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Global Change Biology. 2016;22:151–163. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vila M, et al. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2011;14:702–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schirmel J, Bundschuh M, Entling MH, Kowarik I, Buchholz S. Impacts of invasive plants on resident animals across ecosystems, taxa, and feeding types: a global assessment. Global Change Biology. 2016;22:594–603. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezemer TM, Harvey JA, Cronin JT. Response of Native Insect Communities to Invasive Plants. Annual Review of Entomology. 2014;59:119–U740. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenesi A, et al. Solidago canadensis impacts on native plant and pollinator communities in different-aged old fields. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2015;16:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2015.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallien L, Altermatt F, Wiemers M, Schweiger O, Zimmermann NE. Invasive plants threaten the least mobile butterflies in Switzerland. Diversity and Distributions. 2017;23:185–195. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo L, Nichol C, Shea K. Pollinator floral provisioning by a plant invader: quantifying beneficial effects of detrimental species. Diversity and Distributions. 2016;22:189–198. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis ES, Kelly R, Maggs CA, Stout JC. Contrasting impacts of highly invasive plant species on flower-visiting insect communities. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2018;27:2069–2085. doi: 10.1007/s10531-018-1525-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartomeus I, Vila M, Santamaria L. Contrasting effects of invasive plants in plant-pollinator networks. Oecologia. 2008;155:761–770. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0946-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montero-Castano, A. Interacciones entre polinizadores y la planta exótica Hedysarum coronarium a distintas escalas espaciales PhD thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, (2014).

- 12.Kaiser-Bunbury CN, et al. Ecosystem restoration strengthens pollination network resilience and function. Nature. 2017;542:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein AM, et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2007;274:303–313. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallai N, Salles JM, Settele J, Vaissiere BE. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Economics. 2009;68:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaauw BR, Isaacs R. Flower plantings increase wild bee abundance and the pollination services provided to a pollination-dependent crop. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2014;51:890–898. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colasanti KJA, Hamm MW, Litjens CM. The City as an “Agricultural Powerhouse”? Perspectives on Expanding Urban Agriculture from Detroit, Michigan. Urban Geography. 2012;33:348–369. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.33.3.348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tornaghi C. Critical geography of urban agriculture. Progress in Human Geography. 2014;38:551–567. doi: 10.1177/0309132513512542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stout JC, Tiedeken EJ. Direct interactions between invasive plants and native pollinators: evidence, impacts and approaches. Functional Ecology. 2017;31:38–46. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsson A, Padron B. Does the invasive Lupinus polyphyllus increase pollinator visitation to a native herb through effects on pollinator population sizes? Oecologia. 2014;174:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2756-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traveset A, Richardson DM. Biological invasions as disruptors of plant reproductive mutualisms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila M, et al. Invasive plant integration into native plant-pollinator networks across Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2009;276:3887–3893. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlebois JA, Sargent RD. No consistent pollinator-mediated impacts of alien plants on natives. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:1479–1490. doi: 10.1111/ele.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morales CL, Aizen MA. Invasive mutualisms and the structure of plant-pollinator interactions in the temperate forests of north-west Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Ecology. 2006;94:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01069.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopezaraiza-Mikel ME, Hayes RB, Whalley MR, Memmott J. The impact of an alien plant on a native plant-pollinator network: an experimental approach. Ecol Lett. 2007;10:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramula S, Sorvari J. The invasive herb Lupinus polyphyllus attracts bumblebees but reduces total arthropod abundance. Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 2017;11:911–918. doi: 10.1007/s11829-017-9547-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams NM, Cariveau D, Winfree R, Kremen C. Bees in disturbed habitats use, but do not prefer, alien plants. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2011;12:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2010.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pardee GL, Philpott SM. Native plants are the bee’s knees: local and landscape predictors of bee richness and abundance in backyard gardens. Urban Ecosystems. 2014;17:641–659. doi: 10.1007/s11252-014-0349-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukase J, Simons AM. Increased Pollinator Activity in Urban Gardens with More Native Flora. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research. 2016;14:297–310. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1401_297310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somme L, et al. Food in a row: urban trees offer valuable floral resources to pollinating insects. Urban Ecosystems. 2016;19:1149–1161. doi: 10.1007/s11252-016-0555-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drossart, M., Michez, D. & Vanderplanck, M. Invasive plants as potential food resource for native pollinators: A case study with two invasive species and a generalist bumble bee. Scientific Reports7, 10.1038/s41598-017-16054-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Goodell K, Parker IM. Invasion of a dominant floral resource: effects on the floral community and pollination of native plants. Ecology. 2017;98:57–69. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicolson SW, Wright GA. Plant-pollinator interactions and threats to pollination: perspectives from the flower to the landscape. Functional Ecology. 2017;31:22–25. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanley ME, Awbi AJ, Franco M. Going native? Flower use by bumblebees in English urban gardens. Annals of Botany. 2014;113:799–806. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun SG, Montgomery BR, Li B. Contrasting effects of plant invasion on pollination of two native species with similar morphologies. Biological Invasions. 2013;15:2165–2177. doi: 10.1007/s10530-013-0440-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiedeken EJ, et al. Nectar chemistry modulates the impact of an invasive plant on native pollinators. Functional Ecology. 2016;30:885–893. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albrecht M, Ramis MR, Traveset A. Pollinator-mediated impacts of alien invasive plants on the pollination of native plants: the role of spatial scale and distinct behaviour among pollinator guilds. Biological Invasions. 2016;18:1801–1812. doi: 10.1007/s10530-016-1121-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafferty NE. Effects of global change on insect pollinators: multiple drivers lead to novel communities. Current Opinion in Insect Science. 2017;23:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison T, Winfree R. Urban drivers of plant-pollinator interactions. Functional Ecology. 2015;29:879–888. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byers Diane L., Chang Shu-Mei. Studying Plant–Pollinator Interactions Facing Climate Change and Changing Environments. Applications in Plant Sciences. 2017;5(6):1700052. doi: 10.3732/apps.1700052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tylianakis JM, Didham RK, Bascompte J, Wardle DA. Global change and species interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:1351–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carvell C, et al. Bumblebee family lineage survival is enhanced in high-quality landscapes. Nature. 2017;543:547- + . doi: 10.1038/nature21709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wojcik VA, McBride JR. Common factors influence bee foraging in urban and wildland landscapes. Urban Ecosystems. 2012;15:581–598. doi: 10.1007/s11252-011-0211-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hennig EI, Ghazoul J. Plant-pollinator interactions within the urban environment. Perspectives in Plant Ecology Evolution and Systematics. 2011;13:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2011.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hausmann SL, Petermann JS, Rolff J. Wild bees as pollinators of city trees. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 2016;9:97–107. doi: 10.1111/icad.12145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bronstein Judith L., editor. Mutualism. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaertner M, et al. Non-native species in urban environments: patterns, processes, impacts and challenges. Biological Invasions. 2017;19:3461–3469. doi: 10.1007/s10530-017-1598-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kowarik, I. in Urban Ecology. An International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature (eds John M. Marzluff et al.) 321–338 (Springer, 2008).

- 48.Kaluza BF, Wallace H, Heard TA, Klein AM, Leonhardt SD. Urban gardens promote bee foraging over natural habitats and plantations. Ecology and Evolution. 2016;6:1304–1316. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall DM, et al. The city as a refuge for insect pollinators. Conservation Biology. 2017;31:24–29. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winfree R, Aguilar R, Vazquez DP, LeBuhn G, Aizen MA. A meta-analysis of bees’ responses to anthropogenic disturbance. Ecology. 2009;90:2068–2076. doi: 10.1890/08-1245.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ollerton J. Pollinator Diversity: Distribution, Ecological Function, and Conservation. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2017;48:353–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Côté Isabelle M., Darling Emily S., Brown Christopher J. Interactions among ecosystem stressors and their importance in conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2016;283(1824):20152592. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cierjacks A, et al. Biological Flora of the British Isles: Robinia pseudoacacia. Journal of Ecology. 2013;101:1623–1640. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson DJ, Prasad R. The biology of Canadian weeds. 109. Cytisus scoparius (L.) Link. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 1998;78:497–504. doi: 10.4141/P97-079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachs JL, Simms EL. Pathways to mutualism breakdown. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiers ET, Palmer TM, Ives AR, Bruno JF, Bronstein JL. Mutualisms in a changing world: an evolutionary perspective. Ecol Lett. 2010;13:1459–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.New, T. R. Mutualisms and Insect Conservation. (Springer, 2017).

- 58.Banaszak-Cibicka W, Twerd L, Fliszkiewicz M, Giejdasz K, Langowska A. City parks vs. natural areas - is it possible to preserve a natural level of bee richness and abundance in a city park? Urban Ecosystems. 2018;21:599–613. doi: 10.1007/s11252-018-0756-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banaszak-Cibicka W, Zmihorski M. Wild bees along an urban gradient: winners and losers. Journal of Insect Conservation. 2012;16:331–343. doi: 10.1007/s10841-011-9419-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banaszak-Cibicka W. Are urban areas suitable for thermophilic and xerothermic bee species (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Apiformes)? Apidologie. 2014;45:145–155. doi: 10.1007/s13592-013-0232-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer Leonie K., Eichfeld Julia, Kowarik Ingo, Buchholz Sascha. Disentangling urban habitat and matrix effects on wild bee species. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2729. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martins KT, Gonzalez A, Lechowicz MJ. Patterns of pollinator turnover and increasing diversity associated with urban habitats. Urban Ecosystems. 2017;20:1359–1371. doi: 10.1007/s11252-017-0688-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sivakoff F, Prajzner S, Gardiner M. Unique Bee Communities within Vacant Lots and Urban Farms Result from Variation in Surrounding Urbanization Intensity. Sustainability. 2018;10:1926. doi: 10.3390/su10061926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knight TM, et al. Reflections on, and visions for, the changing field of pollination ecology. Ecol Lett. 2018;21:1282–1295. doi: 10.1111/ele.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pellissier V, Muratet A, Verfaillie F, Machon N. Pollination success of Lotus corniculatus (L.) in an urban context. Acta Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology. 2012;39:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2012.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verboven HAF, Brys R, Hermy M. Sex in the city: Reproductive success of Digitalis purpurea in a gradient from urban to rural sites. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2012;106:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geslin Benoît, Gauzens Benoit, Thébault Elisa, Dajoz Isabelle. Plant Pollinator Networks along a Gradient of Urbanisation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leong M, Kremen C, Roderick GK. Pollinator Interactions with Yellow Starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis) across Urban, Agricultural, and Natural Landscapes. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e86357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parker IM. Pollinator limitation of Cytisus scoparius (Scotch broom), an invasive exotic shrub. Ecology. 1997;78:1457–1470. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1457:PLOCSS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buchholz Sascha, Tietze Hedwig, Kowarik Ingo, Schirmel Jens. Effects of a Major Tree Invader on Urban Woodland Arthropods. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Castro-Díez Pilar, Valle Guillermo, González-Muñoz Noelia, Alonso Álvaro. Can the Life-History Strategy Explain the Success of the Exotic Trees Ailanthus altissima and Robinia pseudoacacia in Iberian Floodplain Forests? PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Packer JG, et al. Native faunal communities depend on habitat from non-native plants in novel but not in natural ecosystems. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2016;25:503–523. doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1059-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pysek P, et al. Successful invaders co-opt pollinators of native flora and accumulate insect pollinators with increasing residence time. Ecological Monographs. 2011;81:277–293. doi: 10.1890/10-0630.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amaya-Marquez M. Floral constancy in bees: a revision of theories and a comparison with other pollinators. Rev Colomb Entomol. 2009;35:206–216. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giovanetti M, Aronne G. Honey bee handling behaviour on the papilionate flower of Robinia pseudoacacia L. Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 2013;7:119–124. doi: 10.1007/s11829-012-9227-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robertson BA, Rehage JS, Sih A. Ecological novelty and the emergence of evolutionary traps. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koch Hauke, Stevenson Philip C. Do linden trees kill bees? Reviewing the causes of bee deaths on silver linden ( Tilia tomentosa ) Biology Letters. 2017;13(9):20170484. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trentanovi G, et al. Biotic homogenization at the community scale: disentangling the roles of urbanization and plant invasion. Diversity and Distributions. 2013;19:738–748. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wehner J, Mittelbach M, Rillig MC, Verbruggen E. Specialist nectar-yeasts decline with urbanization in Berlin. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:45315. doi: 10.1038/srep45315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hernandez, J. L., Frankie, G. W. & Thorp, R. W. Ecology of Urban Bees: A Review of Current Knowledge and Directions for Future Study Cities and the Environment2, 1–15 (2009).

- 81.Lagucki E, Burdine JD, McCluney KE. Urbanization alters communities of flying arthropods in parks and gardens of a medium-sized city. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3620. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Glaum P, Simao MC, Vaidya C, Fitch G, Iulinao B. Big city Bombus: using natural history and land-use history to find significant environmental drivers in bumble-bee declines in urban development. Royal Society open science. 2017;4:170156. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lever JJ, van Nes EH, Scheffer M, Bascompte J. The sudden collapse of pollinator communities. Ecol Lett. 2014;17:350–359. doi: 10.1111/ele.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tylianakis JM, Coux C. Tipping points in ecological networks. Trends in Plant Science. 2014;19:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jain A, Kunte K, Webb EL. Flower specialization of butterflies and impacts of non-native flower use in a transformed tropical landscape. Biological Conservation. 2016;201:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fetridge ED, Ascher JS, Langellotto GA. The Bee Fauna of Residential Gardens in a Suburb of New York City (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 2008;101:1067–1077. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746-101.6.1067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sjoman H, Morgenroth J, Sjoman JD, Saebo A, Kowarik I. Diversification of the urban forest-Can we afford to exclude exotic tree species? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2016;18:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roloff A, Korn S, Gillner S. The Climate-Species-Matrix to select tree species for urban habitats considering climate change. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2009;8:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. Berlin Environmental Atlas. 04.13 Long-term Development of Selected Climate Parameters, https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/umweltatlas/d413_09.htm (2015).

- 90.Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection. Berlin Environmental Atlas. 05.08 Biotopes, https://fbinter.stadt-berlin.de/fb/index.jsp?loginkey=showMap&mapId=k_fb_berlinbtk@senstadt (2016).

- 91.Threlfall CG, et al. The conservation value of urban green space habitats for Australian native bee communities. Biological Conservation. 2015;187:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fischer LK, von der Lippe M, Kowarik I. Urban land use types contribute to grassland conservation: The example of Berlin. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2013;12:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vitkova M, Muellerova J, Sadlo J, Pergl J, Pysek P. Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) beloved and despised: A story of an invasive tree in Central Europe. Forest Ecology and Management. 2017;384:287–302. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kowarik I, von der Lippe M, Cierjacks A. Prevalence of alien versus native species of woody plants in Berlin differs between habitats and at different scales. Preslia. 2013;85:113–132. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morales CL, Traveset A. A meta-analysis of impacts of alien vs. native plants on pollinator visitation and reproductive success of co-flowering native plants. Ecol Lett. 2009;12:716–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Galloni M, Podda L, Vivarelli D, Quaranta M, Cristofolini G. Visitor diversity and pollinator specialization in Mediterranean legumes. Flora. 2008;203:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2006.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McDonnell MJ, Hahs AK. The use of gradient analysis studies in advancing our understanding of the ecology of urbanizing landscapes: current status and future directions. Landscape Ecology. 2008;23:1143–1155. doi: 10.1007/s10980-008-9253-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Senate Department for Urban Development and Housing. Environmental Atlas of Berlin, https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/umweltatlas/edua_index.shtml (2017).

- 99.Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie. Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde. (Springer, 1964).

- 100.Fijen TPM, Kleijn D. How to efficiently obtain accurate estimates of flower visitation rates by pollinators. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2017;19:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ward, K. et al. Streamlined Bee Monitoring Protocol for Assessing Pollinator Habitat. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, 1–16 (2014).

- 102.Zuur, A., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. (Springer, New York, 2009).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Spatial and environmental data at study sites.Appendix 2: Total counts for pollinator taxa interacting with flowering branches of the invasive alien plant Robinia pseudoacacia and the native plant Cytisus scoparius. Diptera s. l. comprised all flies except Syrphidae. Insects were assigned to Hymenoptera s. l. when differentiation between honey bees and wild bees was not possible.

Data Availability Statement

The supplementary data is included as an appendix.