Abstract

The rheumatic heart disease continues to be an important cause of disease burden in India, affecting the population in their prime and productive phase of the life. The prevalence of rheumatic heart disease is varied in different Indian studies, because of the inclusion of different populations at different point of times and using different screening methods for the diagnosis. The data on incidence and prevalence on a nationally represented sample are lacking. There is a need for establishing a population-based surveillance system in the country for monitoring trends, management practices, and outcomes to formulate informed guidelines for initiating contextual interventions for prevention and control of rheumatic heart disease.

Keywords: Prevalence of RHD, Trend of RHD in India

1. Introduction

Rheumatic fever (RF)/rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is the result of autoimmune response triggered by group A Beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis leading to immune-inflammatory injury to cardiac valves. The inflammatory injury of the pericardium and myocardium is transient and self-limiting, without leaving any squeal. The valvular injury is the main cause of acute and long-term morbidity and mortality in patients with acute RF and RHD, respectively.1, 2 The risk of RF/RHD is primarily determined by the host, agent, and environmental factors.3 RF/RHD is considered to be a physical manifestation of poverty. The distribution of the burden of RF/RHD mirrors the distribution of human development index in given geographical region, state, and nation, as well as globally. The socioeconomic state, access, and quality of health-care services are important determinants of the burden of RF/RHD. The incidence of RF/RHD has practically disappeared in developed countries.4 However, RF/RHD continues to be a major cause of disease burden among children, adolescents, and young adults in low-income countries and even in high-income countries with socioeconomic inequalities. The burden of RF/RHD is likely to be variable among countries, within the country, within states depending upon the socioeconomic status and state of health systems.5, 6, 7, 8 The major determinant of the persistent burden of RF/RHD in developing countries are because of poor standards of living conditions, overcrowding, and lack of strong population-based surveillance system for pharyngitis, RF, and RHD for effective implementation of primary and secondary preventive interventions.9, 10 The Indian Council of Medical Research initiated community control and prevention of RF/RHD through hospital-based passive surveillance and implementation of secondary prophylaxis under Jai Vigyan Mission Mode Project from 2000 to 2010.10 There is no structured programme at a national level for prevention and control of RF/RHD. However, changing socioeconomic state, improved living conditions, and improving connectivity and access to health-care centers after adopting a policy of economic liberalization and globalization since 2000 is expected to have translated into a decline in the burden of RF/RHD in India.

2. Methods of detection

The detection of RF/RHD in the population is challenging. The RF and RHD are detected based on symptoms, audible murmurs, and echocardiography evidence of structural and functional abnormalities of the affected valves. The ability to detect murmurs and differentiating functional from pathological murmurs depends upon clinical skills of the physician, settings of auscultation, and so on. Thus, auscultation-based methods of screening RF/RHD have their limited sensitivity and specificity. The morphological and Doppler-based detection of RHD in echocardiography study has high sensitivity and specificity in detection being more objective and subject to validation. The echocardiography detects RHD in patients without being clinically evident called subclinical RHD. The prevalence of subclinical RHD is about seven to ten times higher than clinically evident RHD.50, 52 However, the clinical significance of subclinical RHD needs to be validated in future long-term follow-up studies.

The severity and nature of valvular dysfunction in RHD is variable from patient to patient. The hemodynamically insignificant valvular dysfunctions may be asymptomatic and may not be evident on clinical examination, thus escapes detection. Thus, the variable prevalence of RHD reported may be partly related to differences in the methodology adopted for screening.

3. Data sources for estimation of burden of RF/RHD

Hospital admission data, hospital- and population-based registry data, and population-based active surveillance studies are databases that could be used to estimate the burden and their trends in a population. The hospital admission and hospital-based registries data may provide a rough estimation of the burden of clinically symptomatic patients from the population that is served by the hospital. In hospital admission data, the relative proportion of RF/RHD is subject to vary with changes in the incidence of other diseases and admission policy followed by a given hospital, thus affects the reliable estimate of the trends of the burden of RF/RHD. Population-based registry data provide more reliable estimates of burden and their trends of symptomatic patients. The prospective active surveillance of the population is the only method to determine the burden of any given disease and their trends. In India, there are no hospital- and population-based registries or systematically performed periodic active surveillance studies on the country representative sample to estimate the burden and trends of RF/RHD. The data available are individual investigator-led survey studies performed mostly in school children of urban and some rural areas. The registry studies and population-based survey studies reveal the prevalence of RHD peaks around 30–40 years or so. Thus, prevalence reported in school age group may be an underestimation of disease burden.

4. Epidemiological trends of burden of RHD in India

The burden of RF/RHD has been estimated and reported since 1960s from hospital-based [Table 1], population-based [Table 2], and school-based [Table 3] survey studies, using different case definitions and screening methods. There are no survey studies estimating the burden of RF/RHD based on national- and state-representative sample using uniform screening method at the different timeline to evaluate the trends of the burden of RF/RHD in India.

Table 1.

Hospital-based studies done in India showing hospital admission rates.

Table 2.

Population-based survey studies in India (clinical screening).

| Author | Age group | Number | Study area | Year of survey | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roy20 | 5–30 | 4847 | Ballabhgarh | 1969 | 2.2 |

| Mathur21 | 5–30 | 7953 | Agra | 1971 | 1.8 |

| Berry22 | 5–30 | 19,768 | Chandigarh | 1972 | 1.87 |

| Grover et all23 | 5–15 | 31,200 | Rural area of Ambala, Haryana | 1988–1991 | 0.9 |

| Lalchandani et al24 | 7–15 | 3963 | Rural area of Kanpur | 2000 | 4.58 |

Table 3.

School-based surveys on prevalence of rheumatic heart disease based on clinical screening only.

| Author | Year of survey | Area | Population | Age group | Prevalence /1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICMR25 | 1972–1975 | Agar, Alleppy, Delhi Hyderabad | 133,000 | – | 6–11 |

| Koshi et al26 | 1975–1978 | Vellore | 3890 | 4–16 | 4.4 |

| ICMR27 | 1982–1990 | Delhi | 13,509 | 5–15 | 2.9 |

| ICMR28 | 1984–1987 | Delhi, Varanasi, Vellore | 52,793 | – | 1.0–5.7 |

| Patel et al29 | 1986 | Anand | 11,346 | 8–18 | 2.03 |

| Avasthi30 | 1987 | Ludhiana | 6005 | 6–16 | 1.3 |

| Padamavati31 | 1984–1994 | Delhi | 40,000 | 5–10 | 3.9 |

| Kumar et al32 | 1992 | Churu | 10,168 | 5–15 | 3.34 |

5. Hospital admission data

Hospital admission data [Table 1] show a decline in admission rates of RF/RHD overtime period. RF/RHD accounted for 30%–50% of total admissions until the early 1980s, and it declined to 5%–26% in the late 1990s.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Whether the declining trends in admission rate truly reflects the decreasing incidence is much to be debated. Inadequacy of hospital statistics, varied hospital admission policies, and a large number of corporate hospitals coming up can cause significant bias in hospital-based data. The emergence of an epidemic of coronary artery disease (CAD) and lack of interest among cardiologists in RHD has further compounded the problem. The only useful forgone conclusion can be derived from hospital statistics if the data are derived from the same hospital over a different time period. But data of this kind is scaring. A study from territory care center in Orissa showed no change in admission rate over a decade and the admission rate of 50% in 2013.19

6. Population-based survey studies

Data from population-based surveys [Table 2] are likely to give us reliable estimates of the prevalence of RF/RHD. There are no data available about the prevalence of RF/RHD based on active surveillance studies in a representative sample of the country or the state. The available data are based on estimation performed in cities or rural areas of certain regions of the states in different points of time using either clinical screening method alone or confirmed by echocardiography. The prevalence of RF/RHD reported from cities of Agra, Chandigarh, and Delhi based on clinical examination alone in late 1960s and early 1970s ranged from 1.8/1000 to 4.58/1000.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

7. School-based surveys

7.1. Survey studies with clinical screening method (period 1960s to 1990s)

The estimation of prevalence of RF/RHD among school children performed in the period from 1970s until 1990s was based on clinical screening method alone [Table 3]. Thus, reported figures of prevalence have the limitation of sensitivity and specificity of the cases reported. The reported prevalence from different regions of the country in urban and rural school children varied from 1 to 11 per 1000.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

7.2. Survey studies with clinical screening confirmed by echocardiography (period 1990s to 2000)

The epidemiological studies with clinical screening followed by confirmation of suspected cases with echocardiography using Doppler-based World Health Organization criteria in urban and rural school children in different regions of the country from early 990s to early 2000s reported prevalence ranging from 1.3/1000 to 6.4/1000 [Table 4]. The reported variation in the prevalence of RF/RHD may be an indication of a varied burden of RF/RHD across different regions, urban, rural areas, and/or temporal trends apart from methodological-related factors.23, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Table 4.

School-based surveys on prevalence of rheumatic heart disease based on clinical screening followed by echocardiography confirmation.

| Author | Year of survey | Area | Methodology Clinical + echocardiography of suspected (C + ES) |

Population | Age group | Prevalence /1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grover et al23 | 1988–9123 | Ambala (Rural) | (C + ES) | 31,200 | 5–15 | 2.1 |

| Agarwal et al34 | 1991 | Aligarh (Rural) | (C + ES) | 3760 | 5–15 | 6.4 |

| Gupta et al35 | 199,235 | Jammu | (C + ES) | 10,263 | 6–16 | 1.3 |

| Thakur et al36 | 1992–93 | Shimla (Rural + Urban) | (C + ES) | 10,805 | 5–16 | 4.8 (rural) 1.98 (urban) |

| Vashistha et al37 | 1993 | Agra (Urban) | (C + ES) | 8449 | 5–15 | 1.42 |

| Kaul et al38 | 1999–2000 | Srinagar | (C + ES) | 4125 | 5–15 | 5.09 |

| Jose et al39 | 2001–02 | Vellore (Rural) | (C + ES) | 229,829 | 6–18 | 0.68 |

| ICMR10 | 2002–05 | Kochi, Vellore, Chandigarh, Indore, Shimla, Dibrugarh, Wayanad, Jodhpur, Jammu, Mumbai (Rural + urban) | (C + ES) | 100,269 | 5–15 | 0.43–1.47 |

| Kumar et al40 | 2002–09 | Rupnagar | (C + ES) | 813 | 5–14 | 1 |

| Misra et al41 | 2003–06 | Gorakhpur | (C + ES) | 118,212 | 4–18 | 0.5 |

| Periwal et al42 | 2006 | Bikaner (urban) | (C + ES) | 3292 | 5–14 | 0.67 |

| Negi et al43 | 2007–08 | Shimla (Rural + urban) | (C + ES) | 15,145 | 5–15 | 0.59 (95% C.I. 0.22–0.96/1000), |

| Rama et al33 | 2011 | Prakasam A.P | (C + ES) | 4213 | 5–16 | 0.7 |

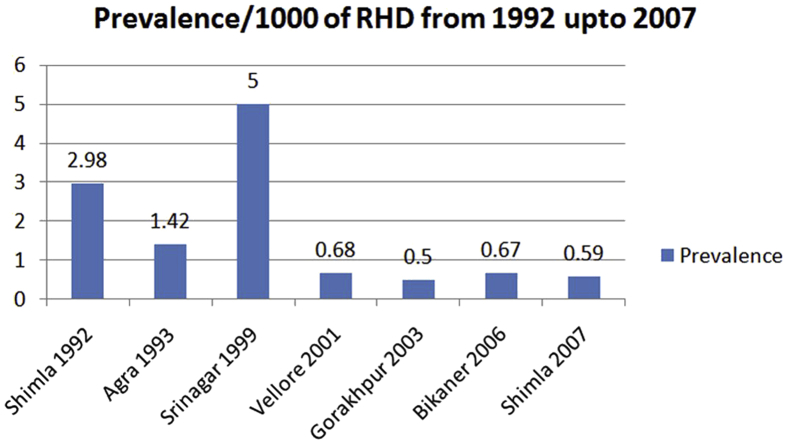

7.3. Survey studies with clinical screening confirmed by echocardiography after 2000

The survey studies in school children performed after 200010, 33, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 using similar screening methods that were followed in 1990s to 2000s revealed consistent decline in the burden to less than 1/1000 across the country compared with figures reported from survey studies before 2000 [Fig. 1, Fig. 2]. The survey study carried out by our group in urban and rural school children of Shimla in early 1990s and mid-2000 using similar screening methods in same geographical region demonstrated about a five-fold decline in the prevalence of RF/RHD.43 This decline was associated with improvement in the indicators of socioeconomic state and health-care services.

Fig. 1.

Trends of changes in prevalence of RF/RHD from early 1990s to late 2000 using clinical screening confirmed with echocardiography.

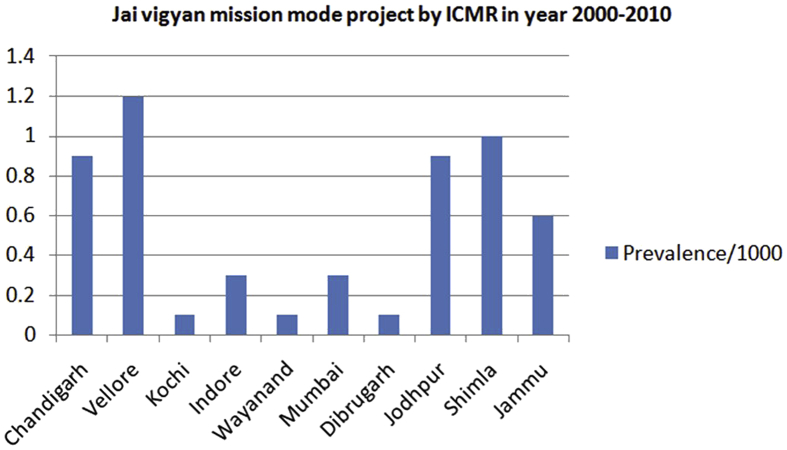

Fig. 2.

- Prevalence of RF/RHD in ICMR-led multicentric survey studies under Jai Vigyan Mission Mode Project from 2000 to 2010.

7.4. Echocardiography-based screening studies in school children after 2000

The auscultation-based screening method has low sensitivity and specificity. The patients with RF/RHD with the mild valvular damage that may be asymptomatic and without an apparent murmur on auscultation thus could be missed on clinical screening. The ability to detect subtle signs of valvular dysfunction also would depend upon clinical skills of the investigator. Thus, the auscultation based detection of RHD has limited sensitivity for detection of children with minimal valvular dysfunction.44 The echocardiography-based survey studies33, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 using evidence-based echocardiography criteria among school children in different parts of the country and other developing countries have reported the prevalence of subclinical RHD many folds higher than clinically evident RHD50 [Table 5].

Table 5.

School-based surveys on prevalence of rheumatic heart disease based on echocardiography as a screening tool.

| Author | Bhaya et al45 | Saxena et al46 | Nair et al47 | Shrestha et al48 | Saxena et al49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical area in state | Bikaner, Rajasthan | Ballabhgarh, Haryana | Trivandrum, Kerala | Sunsari district in Eastern Nepal | Ballabhgarh block of Haryana, Navsari and Dang districts in southern part of Gujarat, Manipur, and Goa. |

| Year of survey | 2010 | 2008–2010 | 2013–2014 | 2012–14 | 2008–2016 |

| Rural/urban | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Rural + urban |

| Age | 6–15 | 5–15 | 5–15 | 5–15 | 5–15 |

| Sample size | 1059 | 6270 | 2060 | 5178 | 16,294 |

| Sampling unit (Schools/population based) | Schools | School | Schools | Schools | Schools |

| Clinical + echocardiography of all (C + EA) | (C + EA) | (C + EA) | (C + EA) | (C + EA) | (C + EA) |

| Echocardiography criteria for diagnosis | WHO | WHO | World heart federation (WHF) | WHF | WHF |

| Prevalence reported with/1000 (95% CI) | 51 (95% CI: 38–64) | 20.4 (95% CI, 16.9–23.9). Clinical prevalence was only 0.8 |

5.83 (95% CI, 2.5–9.1) Clinical prevalence was only 2.4 |

10.2 (95% CI, 7.5–13.0) | 7.7 (95% CI 6.3, 9.0). Borderline RHD: 5.7 Definite RHD: 2 Clinical RHD: 0.36 |

CI, confidence interval; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Moreover, real benefit of screening echocardiography on disease outcome is yet to be proven. Questions remain regarding the natural history of the valve lesions diagnosed by screening echocardiography. Whether the abnormalities detected on portable echocardiography will reverse over time, spontaneously or with secondary prophylaxis, is also unclear. Follow-up data are reported in three observational studies.45, 46, 51 Regression of morphological abnormalities and/or decrease in the degree of valve regurgitation due to RHD was seen in 28%–33% of children over a follow-up period of 6–24 months. Valvular lesions remain the same in majority of children (47%–68%). Only a small minority (8% or less) showed progression of the valvular abnormalities.43 The clinical significance of subclinical RHD needs to be established in appropriately designed large future studies in terms of probability of their progression and efficacy of secondary prophylaxis on the progression of valvular dysfunction.

8. Decline of RHD: is it real?

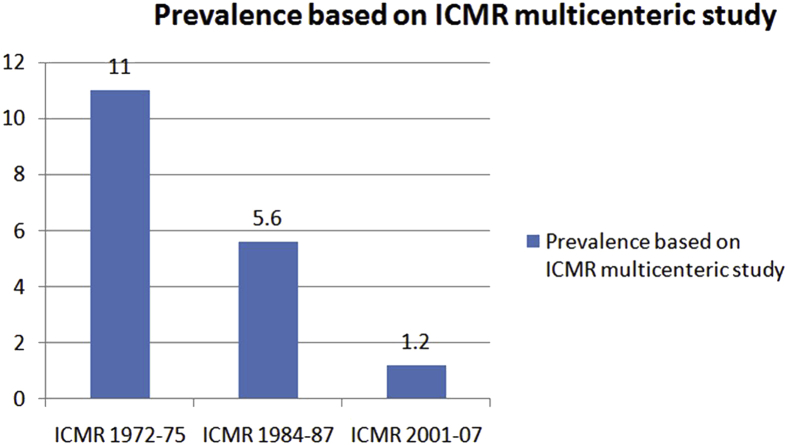

Systematic review of available data on epidemiological studies of RF/RHD conducted in different points of time using clinical screening followed by echocardiography confirmation as the methods of detecting RF/RHD, across the country by individual authors and Indian council of medical research (ICMR) lead multicentric survey studies, suggest declining trends especially after 2000 onwards [Fig. 3]. The two-point survey study carried out over a gap of about 15 years among school children of an urban and rural area of Shimla by our group using similar screening methods also demonstrated five-fold decline in the prevalence of RF/RHD.43 The reasons for declining trends could be the improvement in the socioeconomic state of our country,44 access and affordability of health-care services, and change in health-seeking behavior of the community leading to timely treatment of acute pharyngitis could be some of the important factors responsible for declining incidence of RF/RHD.

Fig. 3.

Trends of change in prevalence of RF/RHD in ICMR-led multicentric survey studies across the country over a period of 40 years.

It is important to recognize that India is witnessing transitions in socioeconomic and health-care sector and also there is a rapid urbanization. However, there are wide disparities in socioeconomic state and quality and access to health-care services across the states, within state, and urban and rural areas. Because RF/RHD is believed to be a physical manifestation of poverty, the burden of RF/RHD is likely to be variable across the state. Unfortunately, no temporal data are available from states with poor health indicators to get insights about the disease trends.

9. Estimated burden of disease

From available data from RHD studies, the estimated average prevalence is 0.5/1000 children in age group of 5–15 years. There are expected to be more than 3.6 million patients of RHD estimated from 2011 census.52 Almost 44,000 patients are added every year, and expected mortality is 1.5%–3.3% per year. These figures still may be the underestimation of disease as no data are available from large populous, underdeveloped states such Bihar, Jharkhand, and so on. Worldwide, there were 319,400 (95% uncertainty interval, 297,300 to 337,300) deaths due to RHD in 2015. Global age-standardized mortality because of RHD decreased by 47.8% (95% uncertainty interval, 44.7 to 50.9) from 1990 to 2015, but large differences were observed across regions. In 2015, the highest age-standardized mortality because of prevalence of RHD was observed in Oceania, South Asia, and central sub-Saharan Africa. In year 2015, the estimated cases of RHD were 33.4 million, and disability adjusted life years because of RHD were 10.5 million.53

9.1. Limitations of all available data on trends of the burden of RF/RHD in India

The prospective active surveillance data on country and/or state representative sample is lacking to evaluate the trends of prevalence and incidence of RF/RHD in our country. There is lack of studies from most of the underdeveloped states of India where the prevalence of the disease is likely to be high. The available reports on the prevalence of RF and RHD also are limited by methodological strength and statistical rigors, variable methods of screening, nonuniform diagnostic criteria, the variable competence of survey teams to detect cases, different referral criteria for echocardiographic screening, and varied echocardiographic criteria used.54 The participation rate of eligible population, urban, rural population, and so on is not reported in a number of studies. Thus, reported figures of a burden of RF/RHD trends need to be viewed in this context. Although results of studies over the time period are showing declining trends of RHD, they cannot be extrapolated to the whole of the country.

10. Challenges and opportunities for prevention and control of RF/RHD

The RF/RHD continues to be an important cause of disease burden in India, affecting the population in their prime and productive phase of the life. India is a young country having 65% of the population younger than 35 years. Because RF/RHD affects the young population, the potential and productivity of the country are affected adversely. Thus, it is imperative that country must invest in prevention and control of RF/RHD. The health professionals have an important advocacy role to play to influence policy makers for initiating policy interventions for prevention and control of RF/RHD. RF/RHD is a preventable cause of disease burden. The most effective intervention for prevention of RF/RHD could be creating enabling environment through policy intervention to promote sanitation, hygiene, better living conditions, nutrition, and access to affordable and quality health-care equitably;55, 56 strengthening of primary health-care services for detection of children with streptococcal pharyngitis; opportunistic screening for RF/RHD; implementing evidence-based primary and secondary preventive intervention; and establishing strong population-based registry centers for surveillance for monitoring trends, management practices, and outcomes that are important to evaluate the impact of primary preventive intervention implemented at community and health system level. The community-level interventions through existing community health volunteers accredited social health activist (ASHAs) would play an important role in primordial and primary prevention through community health literacy initiatives as shown by Cuban experience.57 There is a need for allocating more funds in the health sector in prevention and control programmes rather than in curative health-care services if we aim to decrease the disease burden and promote public health in a cost-effective manner.

RHD has been forgotten by western developed countries, and there is a clear-cut decline in new research in the West. We need to invest in new research to fulfill the gaps of understanding of the disease. Making RHD a notifiable disease such as in New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa and starting a national programme can fill the gaps of implementation in care of RF/RHD.58 Availability of penicillin is a burning issue in most of the states in India. Health-care personnel involved in providing injections must be educated about skin testing, proper technique, and allergic reactions, thus improving the secondary prophylaxis rates which can lead to control of RHD by preventing reoccurrences.59

As we can narrow down and fill the gaps of understanding of disease with new research and carry out better implementation in health-care delivery, we are heading in the right direction to control or even think of eradication the disease.

11. Conclusions

RF/RHD is the disease of poverty. India, having more than 1.3 billion population with wide social and economic disparities RF/RHD, will continue to be a major public health problem. Although data on incidence and prevalence on a nationally represented sample are lacking, there is an indication of declining trends especially after 2000 mirroring with improving economic growth of the country. There is a need for establishing population-based surveillance system in the country for monitoring trends, management practices, and outcomes to formulate informed guidelines for initiating contextual interventions for prevention and control of RF/RHD.

Author contribution

Every author actively involved in preparing the manuscript. The final manuscript is approved by all the authors.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Taranta A., Markowitz M. Kluwer Academic publishers; Boston: 1989. Rheumatic Fever; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishna K. Epidemiology of Streptococcal pharyngitis. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. In: Narula J., Virmani R., Reddy K.S., Tandon R., editors. Rheumatic Fever. American Registry of Pathology Publisher; Washington DC: 1999. pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karthikeyan G., Guilherme L. Acute rheumatic fever. Lancet. 2018 Jul 14;392(10142):161–174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordis L. The virtual disappearance of rheumatic fever in United States: lessons in the rise and fall of disease. Circulation. 1985;72(6):1155–1162. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markowitz M., Kaplan E.L. Reappearance of rheumatic fever. Adv Pediatr. 1989;36:39–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.KaplanEL, Hill H.R. Return of rheumatic fever: consequences, Implications and needs. J Pediatr. 1987;111(2):244–246. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodu S.R.A., Bothing S. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in developing countries. World Health Forum. 1989;10(2):203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seckeler M.D., Hoke T.R. The worldwide epidemiology of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:67–84. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carapetis J.R. Rheumatic heart disease in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:439–441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jai Vigyan Mission mode project on community control of RHD. Non-communicable diseases. Indian Council Med Res Annu Rep. 2007–08:63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutumbiah P. Rheumatism in childhood and adolescence.Part 1. Indian J Pediatr. 1941;8:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanjeevi K.S. Proceedings of Association of Physician India. 1946. Heart disease in south India; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vakil R.J. Heart disease in India. Am Heart J. 1954;48:439–448. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(54)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padamavati S. A five year survey of heart disease in Delhi (1951-1955) Indian Heart J. 1958;10:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devichand Etiology and incidence of heart disease in India with special reference to acquired valvular lesions. Indian Heart J. 1963;15:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur K.S. Problem of heart disease in India. Am J Cardiol. 1960;5:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malhotra R.P., Gupta S.P. Rheumatic heart disease in Punjab with special emphasis on clinical patterns that differ from those reported already. Indian Heart J. 1963;15:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjea J.C. Incidence of rheumatic heart disease in India. Indian Heart J. 1965;17:201–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra T.K., Routry S.N., Bohora M., Patanaik U.K., Sapathy C. Has the prevalence of rheumatic fever/rheumatic heart disease really changed? A hospital based study. Indian Heart J. 2003;55:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy S.B. Indian council of Medical Research; 1968-1969. Prevalence of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease in Ballabhgarh; p. 52. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathur K.S., Banerji S.C., Nigam D.K., Prasad R. Rheumatic heart disease and rheumatic fever-prevalence in a village community of Bichpuri Block Agra. J Assoc Phys India. 1971;19:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry J.N. Prevalence survey of chronic rheumatic fever in Northern India. Br Heart J. 1971;34:134–149. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grover A., Dhawan A., Iyenger S.D., Anand I.S., Wahi P.L., Ganguly N.K. Epidemiology of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in rural community in northern India. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lalchandani A., Kumar H.R.P., Alam S.M. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in rural and urban school children of district Kanpur (Abstract) Indian Heart J. 2000;52:672. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevalence of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease in School Children: Multicentre Study. Indian council of medical research; New Delhi: 1977. p. 108. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koshi G., Benjamin V., Cherian G. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in rural south indian children. Bull World Health Organ. 1981;59:599–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilot Study on the Feasibility of Utilizing the Existing School Health Services in Delhi for Control of RF/RHD. Indian Council of Medical Research; New Delhi: 1990. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Community Control of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart disease. Indian Council of Medical Research; New Delhi: 1994. Report of ICMR Task Force Study. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel D.C., Patel N.I., Patel J.D., Patel S.D. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in school children of Anand. J Assoc Phys India. 1986;34:837–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avasthi G., Singh D., Singh C., Aggarwal S.P., Bidwai P.S., Avasthi R. Prevalence survey of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in urban and rural school in Ludhiana. Indian heart J. 1987;39:26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padamavati S. Present status of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in India. Indian heart J. 1995;47(4):395–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar P., Garhwal S., Chaudhary V. Rheumatic heart disease. A school survey in rural area of Rajasthan. Indian Heart J. 1992;44:245–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumari R.N., Bhaskara R., Patanaik N. Prevalence of rheumatic and congenital heart disease in school children of Andhra Pradesh, South India. J CardioVasc Res. 2013;4:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agarwal A.K., Yunus M., Ahmed J., Khan A. 1995. Rheumatic Heart Disease in India.Perspective in Public Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta I., Gupta M.L., Parihar A., Gupta C.D. Epidemiological survey of rheumatic heart diseases and congenital heart disease in school children. J Indian Med Assoc. 1992;90:57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thakur J.S., Negi P.C., Ahluwalia S.K., Vaidya N.K. Epidemiological survey of rheumatic heart disease among school children in the Shimla hills of Northern India: prevalence and risk factors. J Epidemiological Community Health. 1996;50:57–59. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vashistha V.M., Kalra A., Kalra K., Jain V.K. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in school children. Indian Paediatr. 1993;30:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaul R.R., Masoodi M.A., Wani K.A., Hassan G., Qureshi K.A. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in school children (5-15years) in a rural block of Srinagar. JK Pract. 2005;12:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jose V.J., Gomathi M. vol. 55. 2003. pp. 158–160. (Declining Prevalence of Rheumatic Heart Disease in Rural School Children in India). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar R., Sharma Y.P., Thakur J.S. Streptococcal pharyngitis, rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: eight-year prospective surveillance in Rupnagar district of Punjab, India. Natl Med J India. 2014 Mar-Apr;27(2):70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra M., Mittal M., Singh R. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in school going children of eastern Utter Pradesh. Indian Heart J. 2007;59:42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Periwal K.L., Gupta B.K., Panwar R.B., Khatri P.C., Raja S., Gupta R. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in children of Bikaner. An Echocardiographic study. J Assoc Phys India. 2006;54:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negi P.C., Kanwar A., Chauhan R., Asotra S., T hakur J., Bhardwaj A.K. Epidemiological trends in RF/RHD in school children of Shimla in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:1121–1127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saxena A. Rheumatic heart disease screening by "point-of-care" echocardiography: an acceptable alternative in resource limited settings? Transl Pediatr. 2015 Jul;4(3):210–213. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.06.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhaya M., Panwar S., Beniwal R., Panwar R.B. High prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiography in school children. Echocardiography. 2010;27:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saxena A., Ramakrishnan S., Roy A. Prevalence and outcome of subclinical rheumatic heart disease in India: the rheumatic study. Heart. 2011;97:2018–2022. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nair B, Vishwanthan S. Krisy G, Gupta PN, Nair N, Thakkar A. Rheumatic heart disease in Kerala: a vanishing entity. An echo Doppler study in5-15years schoolchildren. Int J Cardiol.doi org//10.1155.

- 48.Shrestha N.R., Karki P., Mahto R. Prevalence of subclinical rheumatic heart disease in eastern Nepal: a school-based cross-sectional study. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:89–96. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saxena A., Desai A., Narvencar K. Echocardiographic prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in Indian school children using World Heart Federation criteria - a multi site extension of rheumatic study (the e-rheumatic study) Int J Cardiol. 2017 Dec 15;249:438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.09.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saxena A. Increasing detection of rheumatic heart disease with echocardiography. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2014 Sep;11(5):491–497. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2014.930661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paar J.A., Berrios N.M., Rose J.D. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in children and young adults in Nicaragua. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1809–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saxena A. Epidemiology of rheumatic heart disease in India and challenges to its prevention and control. J Preventive Cardiol. 2012;2:256–261. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watkins D.A., Johnson C.O., Colquhoun S.M. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 24;377(8):713–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar R.K., Tandon R. Rheumatic fever & rheumatic heart disease: the last 50 years. Indian J Med Res. 2013 Apr;137(4):643–658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niinan S., Edmond K., Krause V.L. The top end rheumatic heart disease control program. Report on progress. NT Control Bull. 2001;8:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramakrishnan S., Juneja R. Rheumatic heart disease in India: 'Buried alive'. Natl Med J India. 2014 Mar-Apr;27(2):65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nordet P., Lopez R., Duenas A., Sarmiento L. Prevention and control of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: the Cuban Experience(1985-1996-2006) Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008;19:135–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thornley C., McNicholas A., Baker M., Lennon D. Rheumatic fever registers in New Zealand. NZ Pub Health Rep. 2001;8:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markowitz M., Lue H.C. Allergic reactions in rheumatic fever patients in long term benzathine penicillin G: the role of skin testing for penicillin allergy. Paediatrics. 1996;97(6):981–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]