Worldwide, human norovirus (HuNoV) is a major cause of intestinal infectious gastroenteritis, leading to morbidity and mortality in children and the elderly, and it thus has major social and economic influences. Neither an effective vaccine nor an effective treatment is currently available. One of the biggest reasons for the lack of an appropriate prevention or treatment strategy is the unavailability of methods for culturing HuNoV. The recent development of a system of HuNoV replication in human primary intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) has spawned advances in HuNoV characterization and opened up new strategies for HuNoV vaccine development.1 However, this technique currently requires human tissue cells and supplementation with bile, which contains unidentified components.

We and others recently succeeded in establishing a small intestinal type of gut epithelial cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).2, 3, 4 During differentiation of these IECs, LGR5 messenger RNA expression was severely downregulated, whereas the messenger RNAs of both enterocyte markers were dramatically upregulated (Supplementary Figure 1A). When these cells were grown on Transwell membranes (Corning, New York, NY), well-polarized monolayers of IECs were established with the expression of villin-1 (enterocytes) and E-cadherin in cell–cell interactions (Supplementary Figure 1B).5 In addition, polarized IECs showed mature microvillus formation (Supplementary Figure 1C). Furthermore, Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 lectin staining showed that monolayer IECs from iPSCs expressed histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) (Supplementary Figure 1D), which are important receptors for the attachment of GII.4-type HuNoV.1

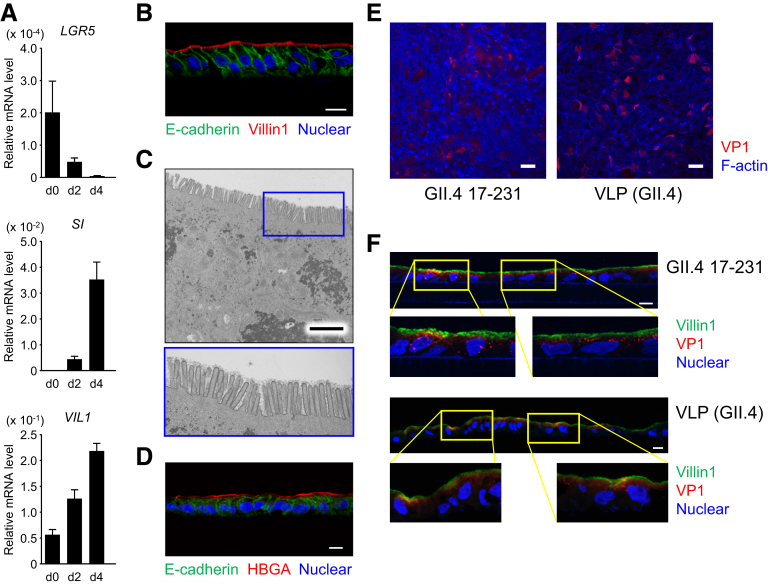

Supplementary Figure 1.

Polarized monolayer of IECs derived from human iPSCs. (A) Differentiation of iPSC-derived IECs to enterocytes. Relative messenger RNA expression of the indicated genes in iPSC-derived IECs during the course of differentiation (days 0, 2, and 4) were determined by qPCR and normalized against the expression of GAPDH. The assays were performed in 3 independent biological replicates. Expression levels are presented as means ± SEM. SI, sucrase isomaltase. (B, D) Immunohistochemical analysis of monolayers harvested with the Transwell membrane after 6 days of culture. Sections were stained with anti-E-cadherin (green) and anti-villin-1 antibodies (red, B) or Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 (red, D), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar = 10 μm. HBGA, histo-blood group antigen. (C) Transmission electron microscopic images of polarized monolayer of human iPSC–derived IECs. Lower panel is a magnification of the area in the blue box in the upper panel. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar = 2.5 μm. (E, F) GII.4 virus and VLPs bound to, and entered, the iPSC-derived IECs. Polarized iPSC-derived IECs on Transwell membranes were incubated with 8.3 × 108 genome equivalents of GII.4 virus or 300 ng of VLPs for 3 hours, and then the Transwell membranes were whole-mount stained with anti-GII.4 antibody (E, red) or were sectioned and stained with anti-GII.4 antibody (F, red) simultaneously with anti-villin-1 antibody (F, green), and then counterstained with DAPI (blue). Lower panels are a magnification of the area in the yellow boxes in the upper panels. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 50 μm (E), 10 μm (F).

We first assessed whether HuNoV could recognize and invade iPSC-derived IECs. Polarized IECs on Transwell membranes were incubated with GII.4 genotype viruses or virus-like particles (VLPs), and the membranes were then whole-mount stained with anti-GII.4-VP1 antibody (Ab) (Supplementary Figure 1E) or sectioned and stained with anti-GII.4-VP1 Ab simultaneously with anti-villin-1 Ab (Supplementary Figure 1F). Both HuNoVs and VLPs were observed in 30%–50% of (villin-1-positive) IECs, as previously reported.1

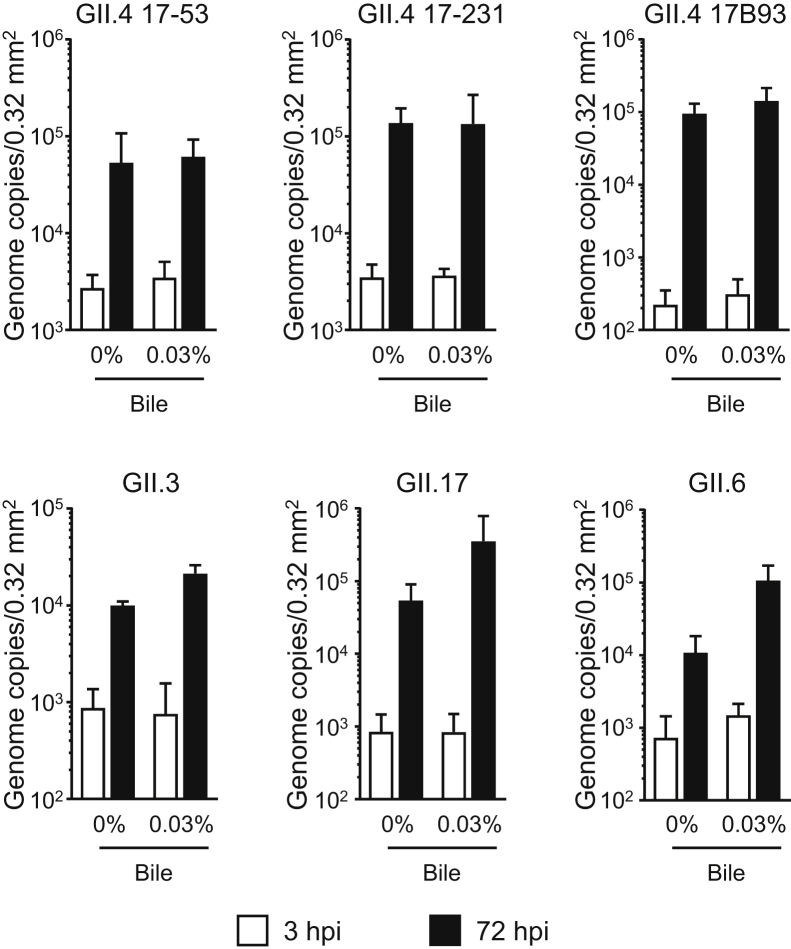

Next, we investigated whether HuNoVs could replicate in human iPSC–derived IECs. The GII.4 genotype can be replicated merely by being added to human primary IECs, whereas replication of some of the other genotypes, such as GI.1, GII.3, and GII.17, requires bile supplementation.1 Consistent with the results of a previous study,1 all GII.4 batches used were able to replicate in iPSC-derived IECs without bile supplementation (Figure 1). Adding bile from 2 days before infection onward seemed to enhance the replication of GII.4 genotype virus (Figure 1). Notably, GII.3 and GII.17, which need bile to replicate in human primary IECs,1 were able to replicate without bile in our iPSC-derived IECs (Figure 1). Furthermore, GII.6-type HuNoV could also replicate without bile in these iPSC-derived IECs (Figure 1). Replication of the GII.4, GII.3, and GII.17 genotypes in our cells was time dependent (Supplementary Figure 2A). The GII.4 (batch 17B93) and GII.17 genotypes could also be passaged in our iPSC-derived IECs, even though the replication of GII.4 virus was severely degraded at passage 3 (Supplementary Figure 2B). It is interesting to note that, in accordance with the report of Ettayebi et al,1 bile supplementation enhanced the replication of all of the studied HuNoV genotypes in iPSC-derived IECs (Figure 1). Nevertheless, because the components of bile that enhance the replication of HuNoVs have not yet been identified, for the industrial application of this technique, it is advantageous that HuNoV replication succeeded in our iPSC-derived IECs without bile supplementation.

Figure 1.

Replication of HuNoVs in IECs derived from human iPSCs. Monolayered human iPSC–derived IECs were inoculated with 2 × 106 genome equivalents of the indicated HuNoV genotypes. Inoculation and sampling were done as described in the Materials and Methods. Viral genome RNA was extracted from both supernatants (ie, those taken at 3 and 72 hours postinfection [hpi]), and then genome equivalents were quantified with reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Samples at 3 hpi were used as references. Each value is representative of at least 3 independent experiments and is shown as the mean ± SD from between 4 and 6 wells of supernatants of each culture group.

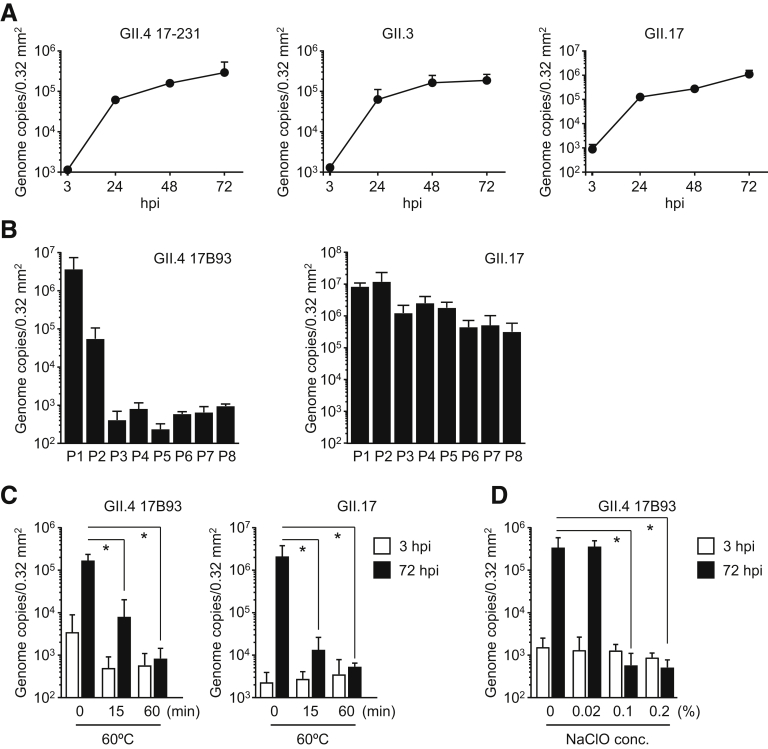

Supplementary Figure 2.

Inactivation of HuNoVs by heat and sodium hypochlorite treatment. Monolayered human iPSC–derived IECs were inoculated with (A) 2 × 106 or (B) 3.7 × 107 (GII.4) or 5.8 × 108 (GII.17) genome equivalents of the indicated HuNoV genotypes. Inoculation and sampling were done as described in the Materials and Methods. Viral genome RNA was extracted from each supernatant sampled at (A) the indicated time or (B) 24 to 48 hpi, and then genome equivalents were quantified with reverse transcriptase qPCR. Each value is representative of at least 3 independent experiments and is shown as the mean ± SD from (A) 6 or (B) 3 wells of supernatants of each culture group. (C) GII.4 and GII.17 HuNoVs (2 × 106 genome equivalents) were incubated at 60°C for the indicated times. (D) GII.4 HuNoVs (2 × 107 genome equivalents) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) at room temperature for 30 minutes, and then diluted with base medium to 2 × 106 genome equivalents/100 μL. Monolayered human iPSC–derived IECs were inoculated with each treated HuNoV. Viral genome RNA was extracted from both supernatants, and the genome equivalents were quantified by reverse transcriptase qPCR. Samples at 3 hpi were used as in the references (A, C, and D). Each value is representative of 3 independent experiments and is shown as the mean ± SD from 6 wells of supernatants of each culture group. *P < .05.

Next, we tested whether our IECs could be used to test for inactivation of HuNoVs. GII.4 or GII.17 viruses were incubated at 60°C. Both HuNoVs were almost completely inactivated after 60 minutes of incubation (Supplementary Figure 2C). Incubation for half an hour with 0.1% sodium hypochlorite was also enough for inactivation of GII.4 viruses (Supplementary Figure 2D).

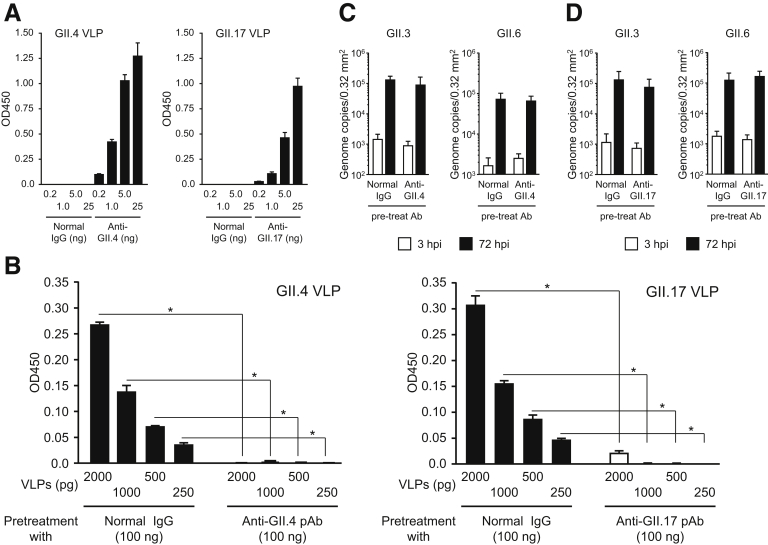

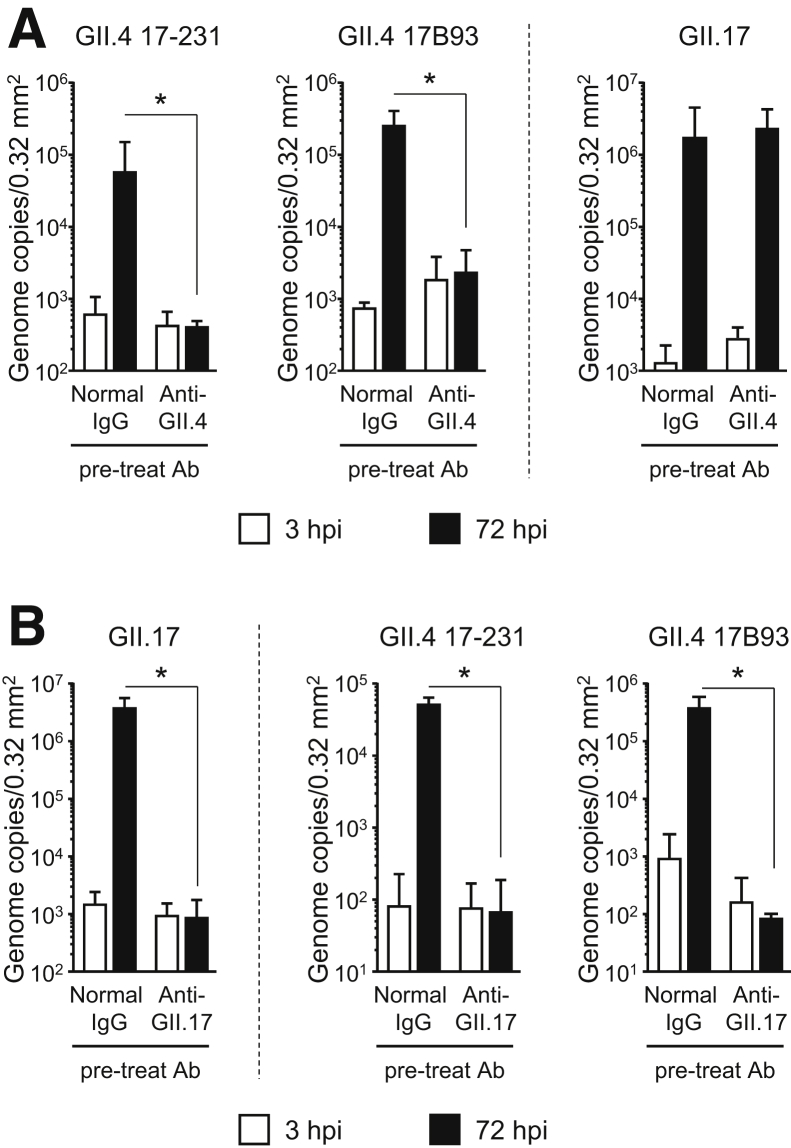

Several HuNoV vaccine candidates, including GII.4 VLPs, are being developed and have progressed to preclinical investigations or clinical trials.6 Although GII.4 is a predominant genotype occurring in HuNoV epidemics, other genotypes—especially GII.2, GII.3, GII.6, and GII.17—are now becoming more frequent.7, 8, 9, 10 Therefore, the induction of cross-reactive Abs with neutralizing activity by mono-genotype VLP vaccination is important from the perspective of efficient vaccine development. We used our iPSC-derived IEC system to examine whether rabbit polyclonal Ab (pAb) against GII.4 and GII.17 VLPs could prevent infection with, and replication of, several genotypes of HuNoV. The homotypic titer of anti-GII.4 pAb was 5 times that of anti-GII.17 pAb (Supplementary Figure 3A). Pretreatment of VLPs with each pAb blocked the binding of VLPs to HBGAs contained in porcine gastric mucin (Supplementary Figure 3B). When GII.4 HuNoVs were preincubated with anti-GII.4 pAb, replication was completely impeded (Figure 2A). We further investigated whether this anti-GII.4 pAb would inhibit other genotypes of GII HuNoVs. It was unable to block the replication of GII.17, GII.3, and GII.6 HuNoVs (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 3C), suggesting that immunization with GII.4 VLPs would not be able to induce neutralization Abs to other genotypes of GII HuNoVs. Pretreatment of GII.17 viruses with anti-GII.17 pAb impaired the replication of this genotype of HuNoV in iPSC-derived IECs (Figure 2B). Interestingly, anti-GII.17 pAb suppressed the replication of GII.4 HuNoV, even though the homotypic titer of anti-GII.17 pAb was about 5 times lower than that of anti-GII.4 pAb (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figures 3A and D). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the cross-reactivity of Abs in blocking other genotypes in the same genogroup of HuNoVs. These data strongly suggest that VLPs of GII.17, but not GII.4, offer potential as multivalent vaccine antigens for HuNoV. Infection with GII.17 HuNoV or vaccination with GII.17 VLPs might induce protection against the major HuNoV genotype, GII.4.

Supplementary Figure 3.

Binding of GII.4 and GII.17 VLPs to histo-blood group antigens is prevented by pre-treatment with each anti-VLP polyclonal antibody (pAb). (A) Homotypic titer of anti-GII.4 and GII.17 pAbs were quantified by enzyme-linked immnosorbent assay. Data are means ± SD from 1 experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) Blocking activity of anti-GII.4 and anti-GII.17 toward VLP–histo-blood group antigen binding was measured by ELISA. Data are mean ± SD from 1 experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. GII.3 and GII.6 HuNoVs (2 × 106 genome equivalents) were incubated with 100 ng of (C) anti-GII.4 or (D) anti-GII.17 antibody, or with normal rabbit IgG, for 1.5 hours. Monolayered human iPSC–derived IECs were inoculated with each treated HuNoV. Viral genome RNA was extracted from both supernatants, and the genome equivalents were quantified by reverse transcriptase qPCR. Samples at 3 hpi were used as references. Each value is representative of 3 independent experiments and is shown as the mean ± SD from 4 to 6 wells of supernatants of each culture group.

Figure 2.

Replication of GII.4 genotype HuNoVs is prevented by pretreatment with either anti-GII.4 or anti-GII.17 pAbs. Before inoculation of IECs, 2 × 106 genome equivalents of each HuNoV genotype was incubated with 100 ng of (A) anti-GII.4 or (B) anti-GII.17 Ab, or with normal rabbit immunoglobulin G, for 1.5 hours. Inoculation, sampling, and quantification of genome equivalents were done as described in the Materials and Methods. Each value is representative of at least 3 independent experiments and is shown as the mean ± SD from between 4 and 6 wells of supernatants of each culture group. *P < .05. hpi, hours postinfection.

We showed here that our established human iPSC–derived IECs could be invaded by, and used as sites of replication of, the GII.3, GII.4, GII.6, and GII.17 genotypes of HuNoV without bile supplementation. Because human iPSCs can be used with fewer ethical concerns than is the case with human biopsy and surgical tissues, iPSC-derived IECs should become useful tools for industrial applications, including the evaluation of vaccine candidates and Ab immune responses in clinical trials. Our findings suggest that, in this system, GII.17 VLPs were more efficient than GII.4 VLPs as vaccine antigens from the perspective of cross-genotype reactivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Makoto Otsu for providing several human induced pluripotent stem cell lines, including TkDN4-M, and Ayae Nishiyama, Chizuru Tsuzuki, Naomi Matsumoto, and Ryoko Asaki for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Shintaro Sato and Akio Suzuki are employed by the Research Foundation for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University. Shintaro Sato, Yoshikazu Yuki, and Hiroshi Kiyono have filed a patent application related to the content of this manuscript. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding The project is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in Aid for Young Scientists B Grant No. 25860353 (to Shintaro Sato) and Scientific Research (C) Grant No. 16K08836 (to Shintaro Sato); a grant from the Joint Research Project of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (to Shintaro Sato); and the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to Shintaro Sato).

Materials and Methods

Cells

The human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line TkDN4-M1 was supplied by the University of Tokyo. Differentiation of human iPSCs into intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) was performed as described previously.2 L cells stably expressing mouse Wnt3a, human R-spondin1, and human noggin (L-WRN) or human R-spondin1 and human noggin (L-RN) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 100 units/mL penicillin plus 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Each conditioned medium (CM) was prepared as described previously.3

Preparation of Virus-like Particles

The nucleotide sequence encoding VP1 of GII.4 and GII.17 was sequenced and cloned into pFastBac Dual Expression Vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each construct was sequenced to be correct and was used to make recombinant baculovirus in a Bac-to-Bac expression system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. High Five cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were infected with each recombinant baculovirus at a multiplicity of infection of 7 plaque-forming units/cell. Six days after infection, culture supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 1 hour. The virus like particles (VLPs) remaining in the supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 2 hours, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), loaded onto a 10%–60% sucrose gradient, and purified by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 hour. The remaining sucrose was removed by dialysis 3 times against 2 L of PBS. VLPs were concentrated by using an Amicon Ultra 30-kDa centrifugal filter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA).

IEC-Culture as Organoids or Monolayered Cells

Organoids that had been cultured in Matrigel (Corning, New York, NY) were washed with PBS and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM) (Wako, Tokyo, Japan). To disrupt the Matrigel and organoids, suspensions were pipetted 30 times by using a P-1000 micropipette, and IECs were filtered with a 50-μm nylon mesh (Sysmex, Hyogo, Japan). We then added 5 times the volume of a base medium (Advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 [Thermo Fisher Scientific] supplemented with 10-mM HEPES [pH 7.3] [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 2-mM Glutamax [Thermo Fisher Scientific], and 100 units/mL penicillin plus 100-μg/mL streptomycin) with 10% defined fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) and collected the cells by centrifugation at 440 g for 5 minutes. The IECs were resuspended in Matrigel with 20% organoid culture medium (base medium supplemented with 25% WRN CM, 1× B-27 [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 50-ng/mL mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF) [Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ], 50-ng/mL human hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN], 10-μM SB202190 [Sigma-Aldrich], and 500-nM A83-01 [transforming growth factor β receptor inhibitor] [Tocris, Bristol, UK]) (plus 10-μM Y-27632) on ice. The suspensions were aliquoted into the wells of a 24-well plate, leaving the border of each well untouched, and solidified in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 10 minutes. Following this, 500-μL organoid culture medium (plus 10-μM Y-27632) was added to each well. The average passaging ratio was 1:16 or 3 × 104/well. The medium was replaced by fresh organoid culture medium every 2–3 days. Passage was performed every 5–7 days.

For human norovirus (HuNoV) inoculation, the dissociated IECs were seeded on 2.5% Matrigel–coated 96-well plates or Transwell membranes (Corning 3470) at 2 × 104/well with 100-μL organoid culture medium (plus 10-μM Y-27632). After 2 days’ cell culture in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, the medium was changed to differentiation medium (base medium supplemented with 12.5% RN CM, 1× B-27, 50-ng/mL mouse EGF, and 500-nM A83-01), and after a further 2 days the medium was changed to differentiation medium with or without 0.03% porcine bile (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were used after a further 2 days’ culture.

Preparation of, and Infection With, HuNoVs

HuNoV-positive stools were suspended in PBS at 10% (w/v) by vigorous vortexing. The suspensions were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 minutes, and the supernatants were serially filtered with 0.45-μm and 0.22-μm filters. The filtered samples were aliquoted and stored at –80°C as undiluted virus solution (see Supplementary Table 1 for strain details). Just before use, each virus solution was diluted to 2 × 107 genome equivalents/mL with base medium. The prepared IECs (3–6 wells/sample) were inoculated with 100 μL (2 × 106 genome equivalents) of diluted virus solutions and then left for 3 hours in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The inoculum was then removed and the cells were washed twice with 150-μL base medium. One hundred microliters of differentiation medium with or without 0.03% bile was added to the cells, which were then pipetted lightly twice and then collected. This step was performed again and the samples were collected as 3 hours postinfection (hpi) reference samples (total 200 μL). Another 100 μL of differentiation medium with or without 0.03% bile was fed into each well, and the mixtures were then cultured for 72 hours in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The supernatants were then collected with 1 wash, in the same way as the 3-hpi reference samples (total 200 μL).

GII.4 (17B93) or GII.17 HuNoV was serially passaged in monolayered human iPSC-derived IECs with 0.03% porcine bile, as described previously. After 24 or 48 hpi, culture supernatants were collected and mixed for subsequent passage (9 wells were used for each passage). Three hours after each infection, supernatants containing the passaged HuNoV were recollected and stocked at –80 °C. One hundred microliters of each supernatant was then subjected to quantification of the genome copies of HuNoV.

For blocking experiments, the diluted virus solutions were incubated with 100-ng anti-VLP (GII.4 or GII.17) polyclonal antibody or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) at 37°C for 90 minutes before inoculation into the prepared IECs (6 wells/sample).

Quantification of Virus Genome Equivalent

A PureLink Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to prepare RNA from diluted virus solutions and samples collected at 3 and 72 hpi. Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was done by using a qPCR Norovirus (GI/GII) Typing Kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japn) and LightCycler 480 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in accordance with the manufacturers’ protocols.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

To perform histo-blood group antigen–binding assay, NUNC MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 100 μL of 10 μg/mL porcine gastric mucin at 4°C overnight. After the plates had been washed and blocked, GII.4 or GII.17 VLPs, which had been pretreated with 100 ng of normal rabbit IgG or anti-GII.4 or anti-GII.17 pAb at 37°C for 90 minutes, were added to the plates, which were then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. The plates were washed with PBS with Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then incubated with 0.5-μg/mL anti-GII.4 or anti-GII.17, respectively, at room temperature for 2 hours. After the samples had been washed with PBS-T, they were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After the samples had again been washed with PBS-T, a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine Microwell Peroxidase Substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) was used for detection in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Results were compared by using an unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test. Statistical significance was established at P < .05. All statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Supplementary Table 1.

List of HuNoVs Used in the Study

| Strain Designation | Genotype_variant | P-Type | Titer (genome equivalents/μL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GII.3 | GII.3 | GII.P12 | 4.3 × 107 |

| GII.4 17-53 | GII.4_Sydney_2012 | GII.Pe | 2.2 × 107 |

| GII.4 17-231 | GII.4_Sydney_2012 | GII.Pe | 8.3 × 107 |

| GII.4 17B93 | GII.4_Sydney_2012 | GII.Pe | 3.7 × 106 |

| GII.6 | GII.6 | GII.P7 | 9.3 × 105 |

| GII.17 | GII.17 | GII.P17 | 5.8 × 107 |

HuNoV, human norovirus.

References

- 1.Ettayebi K. Science. 2016;353:1387–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbester J.L. Humana Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rankin S.A. Nature. 2011;470:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi Y. Stem cell reports. 2018;10:314–328. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi Y. EBioMedicine. 2017;23:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes-Penfield N.W. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1537–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ao Y. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:133–143. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonchan M. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;60:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumthip K. Journal of Medical Virology. 2018;90:617–624. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushima Y. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:21173. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.26.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary References

- 1.Takayama N. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2817–2830. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi Y. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;10:314–328. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi Y. EBioMedicine. 2017;23:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]