Abstract

Background

Understanding and addressing racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities is an important health policy issue, particularly as the Medicare program initiates value-based payments for these institutions.

Methods

Our final cohort included 649,187 Medicare beneficiaries in either the fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage programs, who were 65 and older and were admitted to a skilled nursing facility following an acute hospital stay, from 8,375 skilled nursing facilities. We examined the quality of care in skilled nursing facilities that disproportionately serve minority patients compared to non-Hispanic whites. Three measures, all calculated at the level of the facility, were used to assess quality of care in skilled nursing facilities: (a) 30-day rehospitalization rate; (b) successful discharge from the facility to the community; and (c) Medicare five-star quality ratings.

Results

We found that African American post-acute patients are highly concentrated in a small number of institutions, with 28% of facilities accounting for 80% of all post-acute admissions for African American patients. Similarly, just 20% of facilities accounted for 80% of all admissions for Hispanics. Skilled nursing facilities with higher fractions of African American patients had worse performance for three publicly reported quality measures: rehospitalization, successful discharge to the community, and the star rating indicator.

Conclusions

Efforts to address disparities should focus attention on institutions that disproportionately serve minority patients and monitor unintended consequences of value-based payments to skilled nursing facilities.

Keywords: Medicare beneficiaries, Racial segregation, Racial and ethnic disparities, Site of care, Rehospitalization rates

With close to two million Medicare patients receiving care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) after being discharged from a hospital, improving quality of post-acute care is a high priority for the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and other stakeholders (1–3). Patients discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities too often are readmitted, fail to return to the community, and suffer poor health outcomes, such as functional decline, cognitive impairment, and death (4–9). Post-acute care accounts for $60 billion in annual Medicare expenditures and is a primary driver of regional variations in overall Medicare spending (10–12). While post-acute care providers include home health agencies, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term care hospitals and skilled nursing facilities, care in skilled nursing facilities represented $29 billion in 2014, or about half of Medicare’s post-acute spending in that year (10).

Since 2011, Medicare has implemented efforts to improve quality of post-acute care through accountability, public reporting, and value-based payment strategies. For instance, CMS rates nursing homes using a five-star composite rating scale, which summarizes information about clinical outcomes, processes of care, nurse staffing, and information from onsite inspections (13). In addition, the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014, driven by the rise in post-acute care, updated the Five-Star Quality Rating program by requiring skilled nursing facilities to report rates of potentially preventable 30-days post-discharge readmission measure and successful discharge to the community (14). Consumers can use these quality measures to make informed choices among nursing homes.

These measures of post-acute quality are collected and reported in the aggregate at the skilled nursing facility level, without stratification for vulnerable subgroups such as racial/ethnic minorities. Therefore, they do not provide information about the presence of racial/ethnic disparities in the quality of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities and how skilled nursing facilities that disproportionately serve minority patients fare on quality measures. Understanding these issues is important for three reasons. First, the Institute of Medicine has defined equity as a key dimension of quality and recommended stratified reporting of quality measures by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, as well as other characteristics (15). Second, experts have raised concerns that value-based strategies like pay for performance and public reporting may exacerbate disparities if these strategies penalize providers that disproportionately serve minority and low-income patients (16). Third, prior research has demonstrated racial and ethnic segregation in long-term nursing home care, with African American and Hispanic long-term nursing home residents clustered in a small number of facilities that have more staffing deficiencies, varying levels of financial resource, and deficiencies relative to facilities with higher proportions of white residents (17,18).

There is limited evidence about whether these findings generalize to post-acute patients receiving skilled nursing facility care (19,20). Therefore, this study has two principal objectives. First, using data from all Medicare patients including those in Medicare Advantage, we determined the extent to which African American and Hispanic patients are concentrated within post-acute skilled nursing facilities. Second, we assessed the quality of post-acute care in facilities that disproportionately care for minority patients.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional, facility-level analysis of the association between the racial/ethnic composition of skilled nursing facilities’ patient populations and skilled nursing facilities’ quality of care, as measured by three performance indicators described below.

Sources of Data/Study Population

We merged the Minimum Data Set, the Online survey, Certification and Reporting database, Long-term Care Facts on Care in the United States, and the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File from 2013. The Minimum Data Set includes patient level information on all admissions to all Medicare-certified skilled nursing facilities, including persons enrolled in Medicare Advantage. The Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File provides demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity and ZIP Code of residence. We used the Research Triangle Institute’s race/ethnicity variable with the following mutually exclusive categories from the Medicare master file: non-Hispanic white (hereafter, “white”), non-Hispanic African American (hereafter, “African American”), and Hispanic. This variable has high sensitivity, positive predictive value, and kappa for whites, African Americans, and Hispanics (21).The Online survey, Certification, and Reporting database provides measures of nursing home performance collected in the annual survey and certification process for all Medicare- or Medicaid-certified nursing homes. Long-term Care Facts on Care in the United States contains data on nursing home care in the United States and Nursing Home Compare contained information about nursing home quality star ratings.

We identified 975,203 Medicare beneficiaries in either the fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage programs who were 65 and older who had an admission to a skilled nursing facility following an acute hospital stay (one admission per patient during the study period. Among people with multiple admissions we selected the first admission). We excluded persons who had used long or short-term nursing home care in the prior 2 years because we wanted to focus on incident patients in skilled nursing facilities (N = 225,676). A sensitivity analysis that included all incident patients, including those with prior nursing home use, is described below in the analysis section. We further excluded patients who were not African American, Hispanic, or White (n = 20,631), who went to facilities with fewer than 25 admissions (n = 72,318; about 50% of skilled nursing facilities were also excluded), and those who were in facilities that did not match with the Online survey, Certification, and Reporting or Long-term Care Facts on Care in the U.S. databases or with missing star ratings (n = 6,546), and those with missing covariates (n = 845). Thus, this facility-level analysis was performed on 8,375 skilled nursing homes with 649,187 patients admitted to these facilities.

Quality Measures

Three measures, all calculated at the level of the facility, were used to assess quality of care in skilled nursing facilities: (a) 30-day rehospitalization rate; (b) successful discharge from the facility to the community; and (c) Medicare five-star quality ratings.

The 30-day rehospitalization rate is defined as the proportion of patients who return to the hospital within 30 days following a new admission to a skilled nursing facility from the hospital (22). Each facility’s adjusted rehospitalization rate was calculated using observed rate of rehospitalizations within 30 days divided by the expected rate of rehospitalization within 30 days and multiplied by the national rate. Estimates were calculated using a predictive model that contains 33 different Minimum Data Set variables in six domains: demographic, functional status, prognosis, clinical condition, diagnoses, and services and treatment (23). Successful discharge is defined as discharge to the community within 100 days of skilled nursing facility admission from the hospital and remaining in the community without institutionalization for at least 30 days (24). Each facility’s adjusted rate of successful discharge was calculated using a predictive model of individual-level risk factors (ie, end-stage prognosis, hospice care, physical, and cognitive functioning). Then, individual rates were aggregated to the facility level. Finally, the adjusted successful discharge rate was calculated for each facility by dividing the observed rate by the expected rate and multiplying by the national average (5). These two measures have been widely used to assess quality of long-term care and are reported by the American Health Care Association (22,24). More information on these measures can be found on Long-term Care: Facts on Care (http://ltcfocus.org/). The last measure used was a binary variable of the skilled nursing facility’s Medicare five-star quality rating. Medicare five-star quality rating is a composite measure summarizing skilled nursing facilities’ staffing, quality measures, and health inspections related information with values ranging from 1 star for lowest quality to 5 stars for the highest quality facilities (25). For this outcome we created a binary indicator of whether the nursing home received a score of 4 or 5 stars versus nursing home that received less than 4. More information on these measures can be found on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ website (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/fsqrs.html).

In addition, we reported skilled nursing facilities attributes, including the number of certified nursing assistant hours per resident day; licensed practical nurse per resident day; registered nurse per resident day, for-profit tax status, being part of a chain, and the proportion of facility residents whose primary support is Medicaid.

Analysis

The main unit of analysis was the skilled nursing facility. First, we calculated the percentage of all post-acute care patients in facilities who were African American and the percentage who were Hispanic. Then facilities were categorized into deciles (a) based on the percentage of African American patients, and (b) based on the percentage of Hispanic patients. As the distributions of African American and Hispanic patients differ, so did the categorization of facilities into deciles by these two groups. All the deciles did not contain exactly 10% of the patients since some nursing homes had low concentration of African Americans or Hispanic patients. On average, the proportion of African Americans in skilled nursing facilities ranged from 0 to 49% with 2,559 facilities having no African Americans. Facilities in the lowest-decile by percent of African Americans, which had no African American patients, comprised 22% of patients in our sample. As a result, the second decile had only 391 facilities and the remaining deciles were distributed conventionally with 669–929 facilities. Similarly, the proportion of Hispanics in skilled nursing facilities ranged from 0 to 30% for Hispanics with 3,848 facilities with no Hispanics. Therefore, the lowest-decile facilities by percent Hispanic comprised 35% of patients admitted to facilities without Hispanic patients. The next decile had only 185 facilities and the remaining deciles had anywhere from 512 to 852 facilities (See Supplementary Tables A1 and A2 for distribution of deciles).

We used patient admissions to plot Lorenz curves for the cumulative distribution of admissions of African Americans, and Hispanics in relation to the cumulative distribution of number of skilled nursing facilities, ordered by either the proportion of African American or Hispanic patients within skilled nursing facilities. Then, we described facility characteristics of skilled nursing facilities according to deciles of the proportion of African American and Hispanic patients. We calculated associations between decile of percent African American and decile percent Hispanic in skilled nursing facilities and facility-adjusted 30-day rehospitalization rate; facility-adjusted successful discharge; and high star ratings. Finally, we calculated adjusted means using hospital referral region (26) and aggregated facility-level characteristics, including for-profit status, part of chain, the percentage of residents supported by Medicaid, volume, certified nursing assistant hours per day per resident, licensed practical nurse per hour per resident per day, and registered nurse per hour per day per resident. (Staffing measures were not included in the star rating models since CMS already uses these measures in the composite score, as mentioned above.) Means were calculated using generalized linear models (GLM) with PROC GENMOD; linear models were estimated for rehospitalization and successful discharge rates and modified Poisson with identity link function was used for star ratings (27).

We performed sensitivity analysis including everyone who was admitted to a skilled nursing facility following an acute hospital stay in 2013 (870,817).

We conducted statistical analysis using Statistical Analytics Software 9.4 (28). Graphs were plotted using STATA 14.2 (29). Brown University’s IRB approved the study protocol.

Results

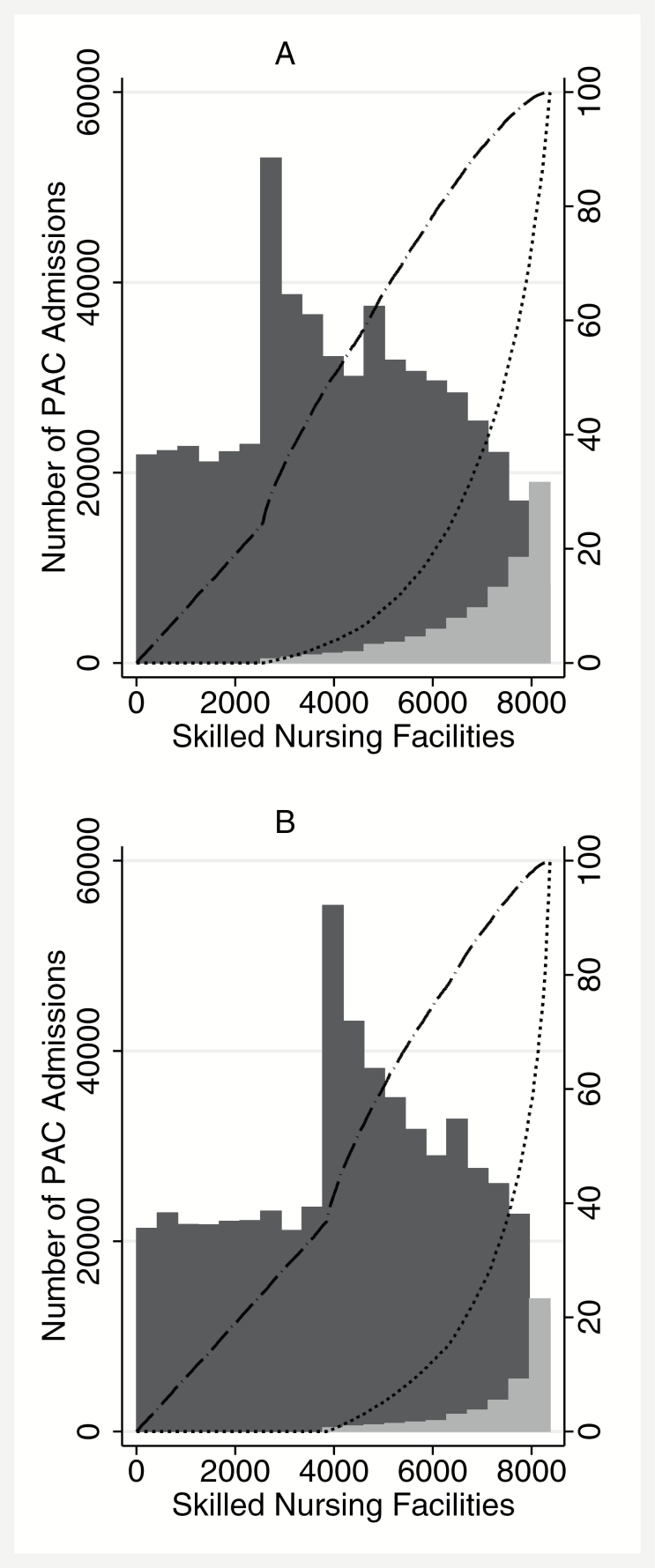

The distribution of admissions across skilled nursing facilities by Medicare beneficiaries are shown in Figure 1, ordered according to the proportion of African Americans (Figure 1A) and Hispanics (Figure 1B) in each facility. Post-acute care admissions to skilled nursing facilities by White patients were mostly to facilities that account for a small number of admissions for African American or Hispanic patients. Approximately 72% (6,059) of facilities had a proportion of African American patients of 10% or below. These skilled nursing facilities accounted for 79% of admissions for White patients but only 20% of admissions for African American patients. The remaining 28% of skilled nursing facilities (2,316) accounted for 80% of all admissions by African Americans and 21% of admissions by White patients. Concentration in skilled nursing facilities among Hispanics was higher than that of African Americans. Approximately 80% (6,660) of facilities with a proportion of Hispanic admission below 6% accounted for 83% of post-acute care admissions for White patients but only 20% of all admissions for Hispanic patients. The remaining 20% of skilled nursing facilities (1,715) accounted for 80% percent of admissions by Hispanic patients (more information about the decile distribution can be found in the Supplementary Tables A1 and A2).

Figure 1.

Estimated national distribution of PAC admissions to skilled nursing facilities by African American (A) and Hispanic (B) Medicare Beneficiaries and White Medicare Beneficiaries. Notes: Distribution of admissions across skilled nursing facilities by White Medicare beneficiaries and African American Medicare beneficiaries (A) and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries (B). Skilled nursing facilities are shown in order of the proportions of their Medicare patients who are African Americans, as opposed to White (A), and the proportions of their Medicare patients who are Hispanics, as opposed to White (B). The estimated number of admissions by White patients (dark gray bars) and African American patients (light gray bars in A) and Hispanic patients (light gray bars in B) is indicated for each facility, with the width of each bar encompassing 418 facilities. The cumulative proportion of admissions by White patients and by African American or Hispanic patients is shown by the cumulative-distribution Lorenz curves.

According to summary statistics by deciles of African American and Hispanic patients admitted in Skilled nursing facilities, excluding the lowest decile with 0% of African American or Hispanic patients, registered nurse hours of care per day per resident decreased as the proportion of African American or Hispanic patients increased. In addition, skilled nursing facilities with the highest fraction of African American patients were more likely to be for profit, part of a chain of nursing homes, and have more residents whose primary support was Medicaid. Skilled nursing facilities that disproportionally treated Hispanics were more likely to be for profit and have a higher proportion of residents whose primary form of support was Medicaid, but not part of a chain. The joint difference across decile was significant statistically (p < .001; Presented in the Supplementary Tables A1 and A2).

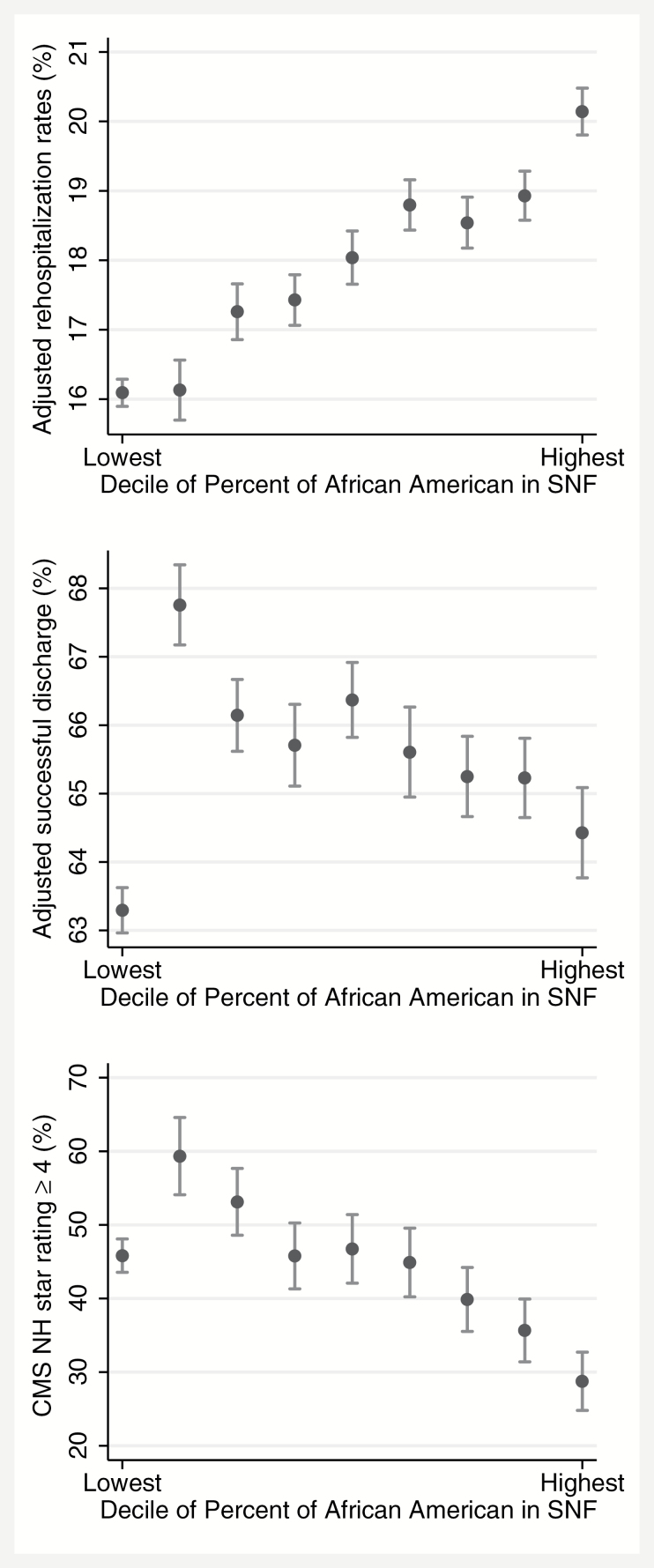

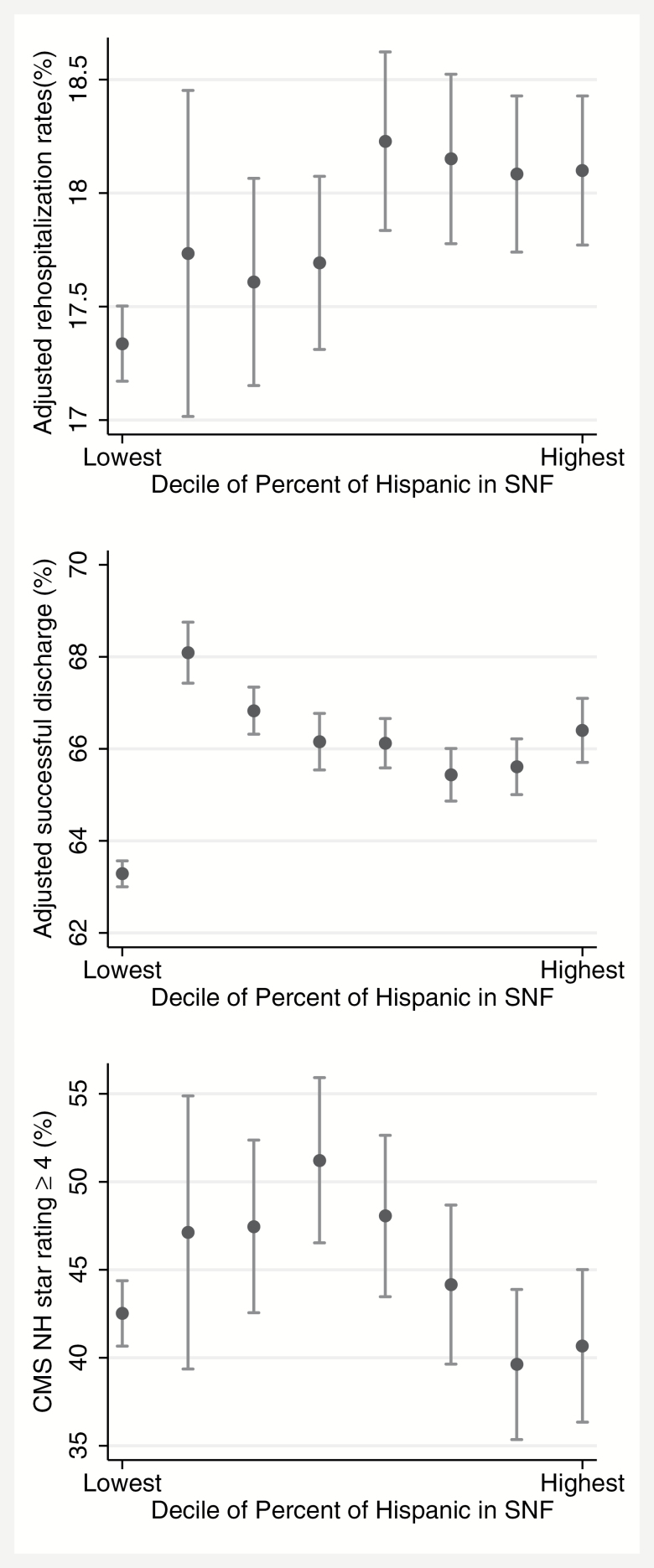

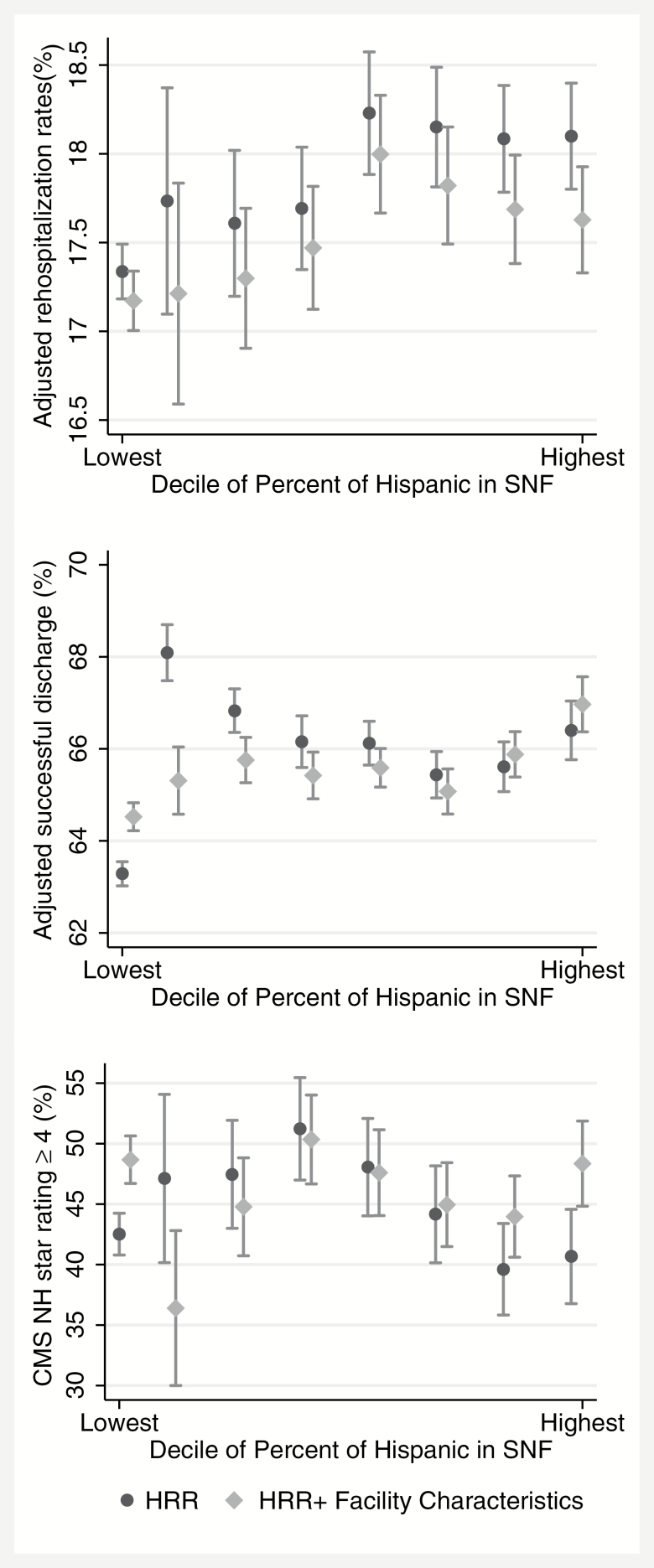

Figures 2 and 3 describe the relationship between the proportion of African American and Hispanic patients and the quality measures in the skilled nursing facility. Facilities that had a greater share of African American patients had substantially higher 30-day rehospitalization rates compared to rates in facilities with lower shares of African Americans. Skilled nursing facilities in the lowest decile of proportion of African Americans had an adjusted 30-day rehospitalization rate of 16.09% (95% CI 15.90–16.29), whereas facilities in the highest decile of proportion of African American patients had an adjusted readmission rate of 20.14% (95% CI 19.80–20.48). Similarly, the adjusted rate of successful discharge and the proportion of skilled nursing facilities with higher star ratings declined as the fraction of African Americans increased from deciles 2 through 9. Unlike the clear trend observed for African American majority facilities, associations between quality indicators in Hispanic majority facilities were more complex. Based on deciles of percentage of Hispanic patients in skilled nursing facilities, those facilities that had a greater share of Hispanics had less than one percentage point difference in 30-day readmission rates in the lowest decile compared to the highest decile. It was 17.34 (95% CI 17.17–17.50) for facilities in decile 1, and 18.10 (95% CI 17.77–18.42) for facilities in decile 8 (See Figure 2). Patients in skilled nursing facilities with lower proportions of Hispanics had a higher rate of successful discharge compared to other deciles with larger proportions of Hispanic patients. Successful discharge in decile 2 was 68.09 (95% CI 67.43–68.75) and 66.40 (95% CI 65.70–67.10) in decile 8. Finally, the last two deciles with higher fraction of Hispanics had fewer proportions of skilled nursing facilities with four or five star ratings.

Figure 2.

Facility level 30-day risk-adjusted rehospitalization rates, facility level risk-adjusted successful discharge, and Medicare nursing home star rating by average percent African Americans admitted to skilled nursing facilities. Note: The unit of analysis is the skilled nursing facility. Graphs are truncated to focus on the differences. The 30-day risk-adjusted skilled nursing facility rehospitalization measure and adjusted successful discharge to the community follow the American Health Care Association methodology (22,24), and Nursing Home Compare Five Star Quality Rating System is designed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (25). There are 33 different demographic and clinical variables included in the risk adjustment model for the rehospitalization measure. Similarly, the discharge measure is risk adjusted using 59 demographic and clinical variables. The overall star rating of is based on facility performance for health inspections, staffing, and quality measures.

Figure 3.

Facility level 30-day risk-adjusted rehospitalization rates, risk-adjusted successful discharge, and Medicare nursing home star rating by average percent Hispanics admitted to skilled nursing facilities.

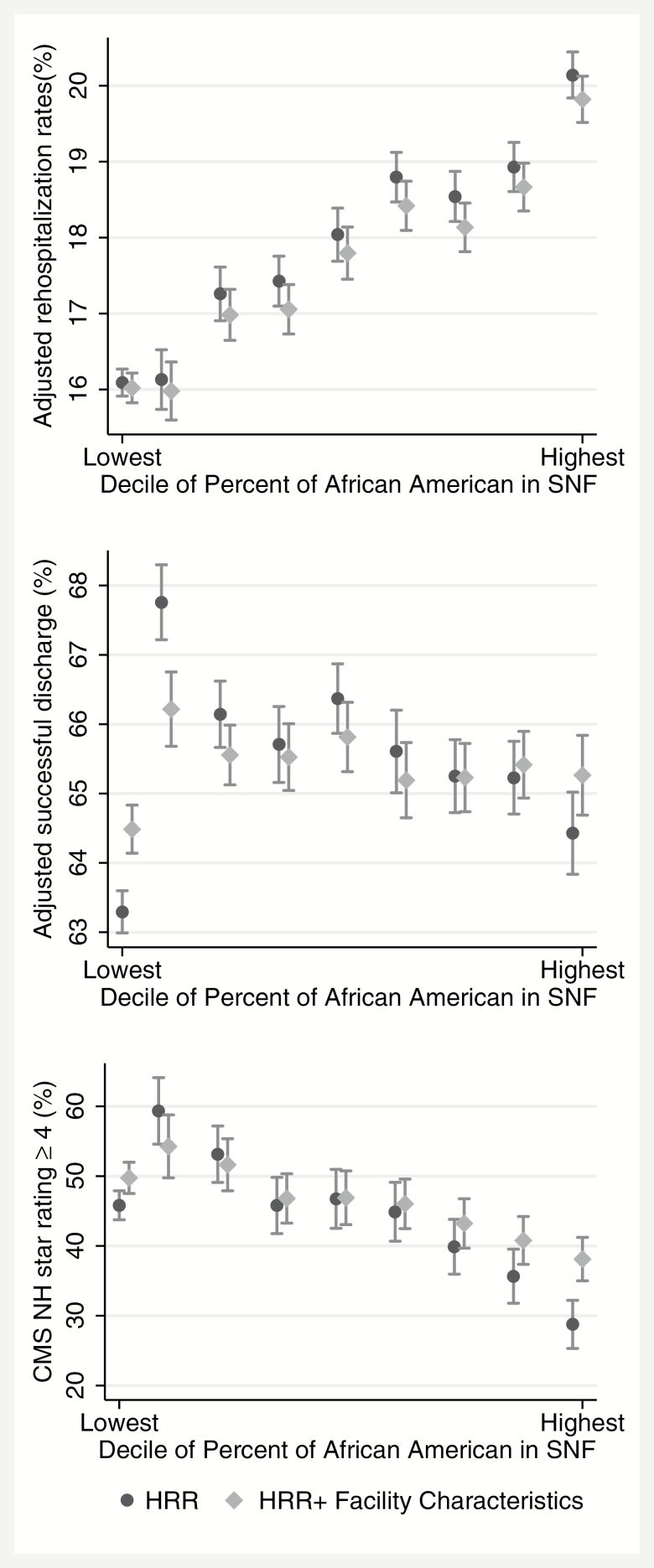

As shown in Figure 4 for deciles of percentage of African American patients in skilled nursing facilities, we obtained similar patterns between facility deciles and these three outcomes after adjusting for hospital referral region. For example, comparing skilled nursing facilities in the lowest and highest decile of percentage of African American patients, there was a 4.05 percentage point difference in 30-day rehospitalization rates (95% CI 3.70–4.40), and 17.06 percentage point difference in facilities with 4–5 star ratings (95% CI 13.04–21.09). Similarly, compared to skilled nursing facilities in the lowest decile of the share of Hispanics, skilled nursing facilities in the highest decile had a 0.76 percentage point (95% CI 0.43–1.10) higher 30-day rehospitalization rate. Regarding star ratings, no significant associations were found when comparing facilities in the extreme deciles of percentage of Hispanic patients. These patterns remained relatively consistent after adjusting for facility characteristics (Figures 4 and 5) and in sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Tables A3–A6).

Figure 4.

Facility level adjusted 30-day rehospitalization rates, facility level adjusted successful discharge, and Medicare nursing home star rating by average percent African Americans admitted to skilled nursing facilities. Means are adjusted by (a) hospital referral region, and (b) hospital referral region and facility characteristics. Note: There were 65,243 patients admitted to facilities in the highest decile share of percent of African American. A 4% difference in rehospitalization and successful rates means that 2,610 more patients get readmitted to the hospital and/or are successfully discharged. Finally, a 17% difference in higher star ratings means that 1,109 less patients go to nursing home with at least four stars.

Figure 5.

Facility level adjusted 30-day rehospitalization rates, facility level adjusted successful discharge, and Medicare nursing home star rating by average percent Hispanic admitted to skilled nursing facilities. Means are adjusted by (a) hospital referral region, and (b) hospital referral region and facility characteristics.

Discussion

In this national study of the quality of post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities that served African American and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries, we found some differences in the quality of care between facilities that serve higher and lower proportions of Hispanic beneficiaries, and more substantial differences in the quality of care between facilities that serve higher and lower proportions of African American beneficiaries. Skilled nursing facilities in the top decile ranked by proportion of African Americans had on average 4.05 percentage point higher 30-day rehospitalization rates compared to facilities that serve no African Americans. For the other two measures examined—successful discharge and Medicare five-star quality rating system—facilities that serve on average less than one percent beneficiaries who were African Americans had 3.33 percentage point higher successful discharge rates and 17.06 percentage point higher star ratings compared to facilities that serve on average 50% of patients who were African Americans. There were 65,243 patients admitted to facilities in the highest decile share of percent of African American. A 4% difference in rehospitalization and successful rates means that 2,610 more patients get readmitted to the hospital and/or are successfully discharged. Finally, a 17% difference in higher star ratings means that 1,109 less patients go to nursing home with at least four stars.

Another important finding in this study, as in previous studies (20), is the segregation of care among post-acute care patients: we found a striking concentration of African American and Hispanic Medicare patients in a relatively small number of skilled nursing facilities. Approximately 80% of all admissions by African American patients occurred in just 28% of skilled nursing facilities. Similarly, 80% of all Hispanic admissions occurred in just 20% of skilled nursing facilities, with about 40% of the facilities being high-Hispanic and African American facilities. Facility nursing staffing declined as the proportion of African American or Hispanic patients increased. As in prior studies long-term care settings (17,18,30), overall patterns show that registered nurse hours of care per day per resident decreased in facilities with higher proportions of African American or Hispanic patients receiving post-acute care. In addition, skilled nursing facilities that disproportionally treated African Americans or Hispanics were more likely to be for-profit and have more residents whose primary support was Medicaid. Understanding and addressing disparities in post-acute care at a national level must include consideration of the concentration of minority groups in skilled nursing facilities with lower performance and nurse staffing.

Studies have found patterns of racial segregation among providers (19,31–35), including nursing homes (17), and association of segregation on disparities in the quality of care. Among post-acute patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities, Li et al. (20) found that African Americans were more likely to be rehospitalized, which was explained by patient and facility characteristics. We extended this work to disparities among Hispanics in post-acute care to demonstrate that African American patients and Hispanic Medicare patients are more likely to go to facilities that are characterized by poor quality measured across different quality constructs, which may include rehospitalization rates, successful discharge, and star-ratings. These findings reinforce the results of other studies in the long-term care setting, demonstrating that African Americans and Hispanics receive care in nursing homes with serious deficiencies, financial vulnerability, and lower staffing ratios (18,30). Smith and colleagues as well as Li and colleagues found that African American residents were more likely to be in facilities with more deficiencies, a high proportion of Medicaid residents, lower percent private pay, and substantial understaffing (20,36). Similarly, Fennell found that facilities that served a predominantly white population were more likely to be deficiency-free, and have higher levels of total direct care staffing, higher ratios of registered nurses to all nurses, higher percentages of private-pay patients, and lower percentages of nursing home residents who were Medicaid-supported (30).

Our study has some limitations. First, our study is cross-sectional in nature and we could not assess the causal relation between race/ethnicity and care in the lower-performing facilities. Second, we were limited in our ability to account for other sociodemographic factors that may influence the quality of care that is received by different racial and ethnic groups across skilled nursing facilities.

There are also several implications for policy and future research of our study. Nursing Home Compare is a tool to support informed decision making for consumers and encourage providers to improve quality of care (37). Yet prior research has found that public reporting on nursing homes has little impact on consumers’ choices (38,39), which may in turn result in minimal changes to quality and performance of nursing homes (34). Initial choice of skilled nursing facility for post-acute care may be guided by hospital discharge planners, and bed availability (40,41). Skilled nursing facilities may also try to select patients that are less likely to require Medicaid-financed long-term care, as such patients typically generate lower reimbursements. Minority patients may be exhibiting race- or distance-based preferences. Patients and their families may choose facilities that are near their communities and/or that have a higher share of residents of their own racial/ethnic background (42). Yet, it may also be a result of access issues and could mean that these lower quality nursing homes are found in more segregated neighborhoods (28). These dynamics not only limit nursing home choice, but may further contribute to nursing home segregation and disparities in quality of care. Another policy implication that arises from these results is that efforts to address racial/ethnic disparities in post-acute skilled nursing care should target efforts and resources for the relatively small number of facilities that disproportionately care for African American and Hispanic patients (18,30).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has implemented a series of pay-for-performance measures designed to reward nursing homes for achieving better performance. In terms of cost, a 4% difference in rehospitalization rates for nursing homes in the highest decile may translate into ~$26 million in Medicare costs (43). The Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing Program will start in 2019. It is designed to promote better outcomes and experiences for post-acute skilled nursing care patients using measures assessing all-cause and potentially preventable readmissions (44). Yet our study suggests that this initiative has the potential to penalize skilled nursing facilities with higher proportions of minority patients, which may take away the resources they need to effect improvement as they tend to have worse performance on those measures. Policymakers should monitor the unintended consequences of public reporting and other quality programs, so that these initiatives ideally reduce disparities rather than erode quality of care in skilled nursing facilities with higher proportion of minority patients. Financial penalties may lead minority-serving institutions to further decrease staffing or to close, which would restrict access to these institutions (45). Lower performing skilled nursing facilities could be forced to close, and an unintended consequence may be restricting access to SNF care to African Americans and Hispanics who are admitted to these institutions (30).

Conclusion

Our study documents substantial racial and ethnic concentration of post-acute patients in a small number of skilled nursing facilities. Skilled nursing facilities with higher fractions of African American patients have markedly worse rates of 30-day rehospitalization, successful discharge to the community, and composite star ratings. There was a more modest inverse gradient between fraction of Hispanic patients and quality. Achieving health care equity in post-acute care may require targeted quality improvement efforts for skilled nursing facilities that disproportionally serve minority patients and monitoring of potential adverse consequences of pay-for-performance and public reporting programs for minority-serving facilities.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences online.

Funding

National Institute on Aging Grant Nos. P01AG027296-07 and P01A G027296-07S1. The National Institute on Aging had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Trivedi reports consulting for the Merck Manual.

Dr. Mor is the Chair of the Independent Quality Committee at HCR ManorCare and is compensated for this service. He is a paid consultant to NaviHealth, Inc. and chairs their Scientific Advisory Board. He is a former Director at PointRight, Inc. While he no longer provides any services or holds any positions at PointRight, he still has a small amount of equity in the company.

References

- 1. Acumen, LLC. Measure Specifications: Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary – Post-Acute Care Skilled Nursing Facility, Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility, and Long-Term Care Hospital Resource Use Measures [Internet]. Burlingame, CA: Acumen, LLC; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/2016_07_20_mspb_pac_ltch_irf_snf_measure_specs.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. IMPACT Act of 2014 Data Standardization & Cross Setting Measures [Internet] 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/IMPACT-Act-of-2014/IMPACT-Act-of-2014-Data-Standardization-and-Cross-Setting-MeasuresMeasures.html. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- 3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. PAC Quality Initiatives [Internet] 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/PAC-Quality-Initiatives.html Accessed February 16, 2017.

- 4. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:57–64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gozalo P, Leland NE, Christian TJ, Mor V, Teno JM. Volume matters: returning home after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2043–2051. doi:10.1111/jgs.13677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, Sood N, Escarce JJ. Medicare spending and outcomes after postacute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care. 2010;48:776–784. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e359df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Segal M, Rollins E, Hodges K, Roozeboom M. Medicare-medicaid eligible beneficiaries and potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014:E1–E10. doi:10.5600/mmrr.004.01.b01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rahimi-Movaghar V, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR. Trauma and long-term mortality. JAMA. 2011;305:2413–2414. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hakkarainen TW, Arbabi S, Willis MM, Davidson GH, Flum DR. Outcomes of patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities after acute care hospitalizations. Ann Surg. 2016;263:280–285. doi:10.1097/SLA. 0000000000001367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program [Internet] 2016:107–127. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/june-2016-data-book-health-care-spending-and-the-medicare-program.pdf AccessedApril 16, 2017.

- 11. Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:692–694. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1315607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Institute of Medicine. Interim Report of the Committee on Geographic Variation in Health Care Spending and Promotion of High-Value Care: Preliminary Committee Observations [Internet] 2013. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18308/interim-report-of-the-committee-on-geographic-variation-in-health-care-spending-and-promotion-of-high-value-care AccessedApril 18, 2017.

- 13. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Five-Star Quality Rating System [Internet] 2017. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/fsqrs.html AccessedApril 18, 2017.

- 14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Quality Reporting Program Measures and Technical Information [Internet] 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Skilled-Nursing-Facility-Quality-Reporting-Program/SNF-Quality-Reporting-Program-Measures-and-Technical-Information.html Accessed April 18, 2017.

- 15. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care [Internet]. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220358/. Accessed April 18, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Casalino LP, Elster A, Eisenberg A, Lewis E, Montgomery J, Ramos D. Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities?Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w405–w414. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82:227–256. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fennell ML, Clark M, Feng Z, Mor V, Smith DB, Tyler DA. Separate and unequal access and quality of care in nursing homes: transformation of the long term care industry and implications of the research program for aging hispanics. In: Angel JL, Torres-Gil F, Markides K, eds. Aging, Health, and Longevity in the Mexican-Origin Population [Internet]. Boston, MA: Springer; 2012:207–225. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4614-1867-2_16. Accessed January 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y, Yin J, Cai X, Temkin-Greener J, Mukamel DB. Association of race and sites of care with pressure ulcers in high-risk nursing home residents. JAMA. 2011;306:179–186. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y, Glance LG, Yin J, Mukamel DB. Racial disparities in rehospitalization among medicare patients in skilled nursing facilities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:875–882. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.300055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eicheldinger C, Bonito A. More Accurate Racial and Ethnic Codes for Medicare Administrative Data [Internet] 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/08springpg27.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2017.

- 22. American Health Care Association. 30-Day Risk-Adjusted SNF Rehospitalization Measure [Internet] 2017. https://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/trendtracker/Documents/Rehospitalization%20Help%20Doc.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 23. Thomas KS, Mor V, Tyler DA, Hyer K. The relationships among licensed nurse turnover, retention, and rehospitalization of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2013;53:211–221. doi:10.1093/geront/gns082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Health Care Association. Discharge to Community Measure [Internet]. 2017. https://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/trendtracker/Documents/Discharge%20to%20Community%20Help%20Doc.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Design for Nursing Home Compare Five-Star Quality Rating System: Technical Users’ Guide [Internet] 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/usersguide.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 26. The Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences: Dartmouth Medical School. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care [Internet] 1996. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/atlases/96Atlas.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 27. Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. SAS Institute. SAS 9.4 for windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institue Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fennell ML, Feng Z, Clark MA, Mor V. Elderly Hispanics more likely to reside in poor-quality nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:65–73. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–584. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa040609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1177–1182. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43:308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mukamel DB, Haeder SF, Weimer DL. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to health care quality: the impacts of regulation and report cards. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:477–497. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082313-115826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Mushlin AI. Referrals to high-quality cardiac surgeons: patients’ race and characteristics of their physicians. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1276–1295. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773. 2006.00535.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across U.S. nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1448–1458. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Werner R, Stuart E, Polsky D. Public reporting drove quality gains at nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1706–1713. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Werner RM, Norton EC, Konetzka RT, Polsky D. Do consumers respond to publicly reported quality information? Evidence from nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2012;31:50–61. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco. 2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grabowski DC, Town RJ. Does information matter? Competition, quality, and the impact of nursing home report cards. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1698–1719. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Showalter S. A Perfectly Legal Way to Help Patients Pick Higher-Quality Post-Acute Providers [Internet] 2015. http://www.hfma.org/Content.aspx?id=29698 Accessed February 16, 2017.

- 41. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Hospital Discharge Planning [Internet] 1997. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-94-00320.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- 42. Rahman M, Foster AD. Racial segregation and quality of care disparity in US nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2015;39:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Levinson D; Inspector General Medicare Nursing Home Resident Hospitalization Rates Merit Additional Monitoring [Internet]. Washington, DC: US Office of Inspector General; 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-11-00040.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing Program (SNFVBP) [Internet] 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Other-VBPs/SNF-VBP.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- 45. Feng Z, Lepore M, Clark MA et al. Geographic concentration and correlates of nursing home closures: 1999–2008. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:806–813. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.