Abstract

Background

Linear Array Genotyping Test (LA) is one of the gold standards used for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping, however, since its launching in 2006, new HPV genotypes are still being characterized with the use of high specificity techniques such as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Derived from a previous study of the IMSS Research Network on HPV, which suggested that there might be cross-reaction of some HPV genotypes in the LA test, the aim of this study was to elucidate this point.

Methods

Double stranded L1 fragments (gBlocks) from different HPVs were used to perform LA test, additionally, 14 HPV83+ and 26 HPV84+ cervical samples determined with LA, were individually genotyped by NGS.

Results

From the LA HPV83+ samples, 64.3% were truly HPV83+, while 42.9% were found to be HPV102+. On the other hand, 69.2% of the LA HPV84+ samples were HPV84+, while 3.8, 11.5 and 30.8% of the samples were indeed HPV 86, 87 and 114 positive, respectively. Additionally, novel nucleotide changes in L1 gene from HPV genotypes 83, 84, 87, 102 and 114 were determined in Mexican cervical samples, some of them lead to changes in the protein sequence.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that there is cross-hybridization between alpha3-HPV genotypes 86, 87 and 114 with HPV84 probe in LA strips and between HPV102 with HPV83 probe; this may be causing over or under estimation in the prevalence of these genotypes. In the upcoming years, a switch to more specific and sensitive genotyping methods that detect a broader spectrum of HPV genotypes needs to be implemented.

Keywords: Cervical samples, HPV, L1 mutations, Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test, Next-Generation Sequencing, Cross-hybridization

Background

Human Papillomaviruses (HPV) belong to a diverse group of small non-encapsulated dsDNA viruses that have evolved over millions of years [1]. HPV classification and nomenclature is defined by the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) and the HPVs described to date are classified in different genera and species based on L1 gene sequence percentages of identity [2]. HPVs belong to five different genera called Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, Mu- and Nu-PVs [3]. Each HPV is adapted to infect a specific epithelial tissue such as skin or mucosa, and most of them do not cause an apparent pathology and are cleared in some months or years. However, some Alpha HPV genotypes are medically relevant because of their carcinogenic potential if the infection persists over the years. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 12 HPV genotypes are defined as oncogenic or high-risk (HR-HPVs): 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58 and 59. Some other genotypes are possibly carcinogenic while most of the remaining viruses are non-carcinogenic or low-risk (LR-HPV) [2, 4]. HPV16, the most prevalent genotype worldwide, is found in around 60% of cervical cancer samples according to a meta-analysis performed in 115,789 HPV-positive women, followed by HPV18 and HPV45 [5].

Cervical cancer (CC) is the most common HPV-related cancer and consequently HR-HPVs are widely studied to better understand and treat HPV-driven cervical carcinogenesis. However, there are not so many studies on LR-HPVs and HPV coinfections, which could unravel important information on their role in either carcinogenesis or viral clearance. In industrialized countries, CC screening is performed with three main methods: cytology, DNA or RNA detection of HR-HPVs or cytology-HPV co-testing [4]. HPV genotyping tests are widely used worldwide in many laboratories and there is an increased need to develop reliable and cheaper tests that detect most of the high and low-risk HPVs described to date. The Linear Array Genotyping test from Roche (LA), launched in 2006, allows the detection of 37 HPV genotypes (6, 11, 16 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 (MM9), 81, 82 (MM4), 83 (MM7), 84 (MM8), IS39, and CP6108) and is one of the gold standards used for genotyping [6–8]. Moreover, while new HPV genotypes are still being characterized, the use of high-throughput screening technologies such as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), allows genotyping of a broader spectrum of HPVs when compared to the commercially available tests. In a previous study of our research group, LA and 454 NGS were performed in cervical samples from Mexican women. In some of the samples, not all HPV genotypes detected with LA were confirmed by NGS (indicating the possible non-specific detection of the LA), whereas five HPVs that cannot be detected with the LA test were detected by NGS: 32, 44, 74, 102 and 114 [9]. This finding suggested that there could be a cross-reaction between those HPVs not included in LA and the probes of the test.

The aim of the present study was to determine how specific is the worldwide used LA test, by looking at a possible cross-hybridization in the LA strips and to estimate the frequency of the HPVs that could cross-react. In this work, mutations in the PGMY11/09 amplified L1 gene fragment from the HPV genotypes that cross-hybridized in LA test were described, to see if new variants or subtypes of those HPVs could be infecting the Mexican population.

Methods

Sample collection

In the present study, cervical samples were collected from women who attended a medical examination at the Dysplasia Clinic - Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente (CMNO-IMSS) in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico; and from diverse Hospitals around Mexico as previously published [9, 10]. The sample recruitment was done from 2014 to 2017 by gynecologists, with a cytobrush inserted into the endocervical canal. From those samples, 535 were positive to HPV by using Linear Array Genotyping Test.

HPV genotyping by Linear Array

Total DNA was extracted from cervical samples collected in Preserv-Cyt medium solution (Cat. no. 70097-002, Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) and purified using the AmpliLute Liquid Media Extraction Amplicor kit (Cat. no. 03750540190; Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA.) following the manufacturer instructions. All samples were genotyped by Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (Cat. no. 03378179190, Roche Molecular Systems) as previously described [9].

Linear Array test using L1 gBlocks

Double stranded genomic blocks (gBlocks) were designed by choosing the PGMY11/09 amplified L1 sequences from HPV reference genotypes 32 (X74475), 44 (U31788), 74 (AF436130), 86 (AF349909), 87 (AJ400628), 102 (DQ080083) and 114 (GQ244463), and were synthetized by IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralvillle, Iowa, USA). The gBlocks were resuspended in 1X TE, and subsequently 10 pg of each specific gBlock were taken to proceed with LA.

Next-generation sequencing

The positive samples to HPV83 and HPV84 determined by LA that showed a clear hybridization band in the HPV strips, were selected to perform NGS. First, the DNA of each sample was amplified by conventional PCR with the PGMY primers [11]. Then, a second PCR reaction was performed using the same primers coupled to a universal tail sequence, as previously described [9]. Briefly, the PCR products were quantified with the fluorometry assay Qubit dsDNA HS (Cat. no. Q32854, Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA), subsequently, each sample was diluted to 5x109 molecules per microliter. Then, individual barcodes were added to each sample using the 454 MIDs from Multiplicom NV CFTR kits (Cat. no. ML-0008.192, ML-0016.192 and ML-0124.192, Molecular Diagnostics, Niel, Belgium). Each sample was purified with the Agentcourt AMPure XP beads (Cat. no. A63880, Beckam Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA, USA) and evaluated with the Agilent DNA 1000 kit (Cat. no. 5067-1504, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on the 2100 Bionalyzer (Cat. no. G2939BA, Agilent Technologies). For sequencing, GS Junior Titanium kits were used in a GS Junior Sequencer, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Cat. no. 05996562001, 05996589001, 05996597001, 05996619001, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Data analysis

The sequencing data were first analyzed with the FastQC tool to determine the quality of the sequences [12]. Then, to identify specific HPV genotype sequences present in each cervical sample, the Roche GS Reference Mapper v3.0 software was used, taking as references all the L1 sequences reported in the Papillomavirus Episteme (PaVE) database [13]. The parameters considered for mapping were the following: trimming of adapters and primers, 90% of minimum overlap identity, Phred score ≥ 20, minimum read length of 100 bp and exclusion of all the repeated reads. All HPV raw sequence reads were uploaded in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (accession number SRP130362).

Among the nucleotide changes observed in the L1 gene from HPVs 83 (AF151983), 84 (AF293960), 86 (AF349909), 87 (AJ400628), 102 (DQ080083) and 114 (GQ244463), we described those that were present in all the reads from a specific HPV with a minimum depth of 20 reads or those found in two or more distinct samples (independently of the reads number).

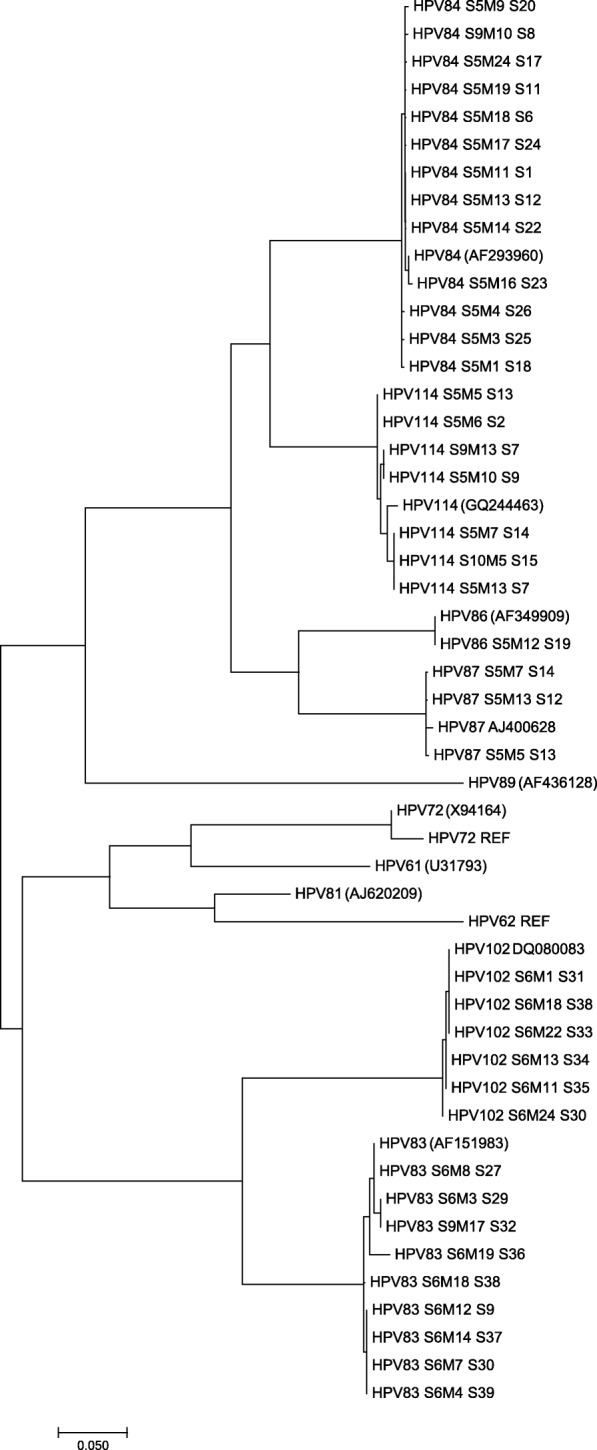

Finally, a phylogenetic tree was constructed with L1 consensus sequences from HPV83, 84, 86, 87, 102 and 114 from each sample, including the L1 reference sequences from all alpha3-papillomaviruses. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 7 software by using the muscle algorithm for the alignment of sequences and the evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model [14, 15]. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated and the tree with the highest log likelihood was chosen.

Results

Cross-hybridization between HPV genotypes in Linear Array Genotyping test

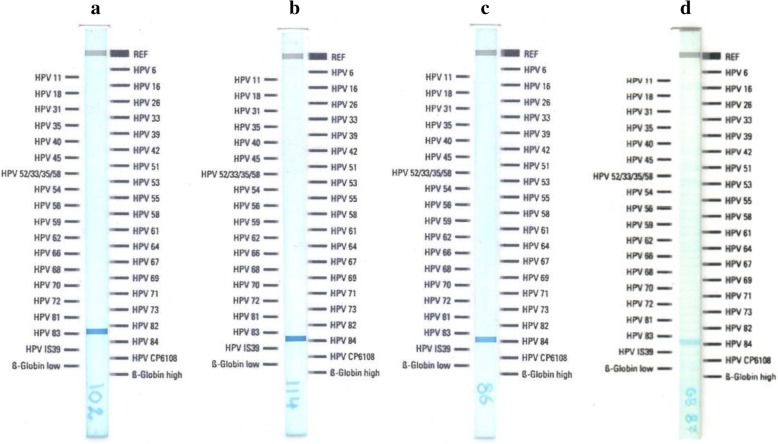

Previous results of our working group showed that in some cervical samples, not all HPV genotypes detected with LA were found by NGS; in contrast, other genotypes such as 32, 44, 74, 102 and 114 were detected only with NGS. These findings suggested that positivity to some HPVs in LA could be due to the presence of other genotypes not included in the test. To see if there is a cross-reaction between HPVs 32, 44, 74, 102 and 114 (not included in the LA test) with any probe of the LA strip, amplification and hybridization was performed using as template the gBlocks of an L1 fragment from each of those HPVs. HPV32, 44 and 74 did not cross-hybridize with any of the HPV probes included in LA test (data not shown). However, L1 gBlocks from alpha-3 HPV102 and HPV114 cross-linked with HPV83 and HPV84 probes, respectively (Fig. 1a and b). Since also HPVs 86 and 87 are alpha-3 genotypes not included in LA, the test was therefore performed additionally with HPV86-L1 and HPV87-L1 gBlocks. Both HPVs showed cross-reactivity with HPV84 (Fig. 1c and d).

Fig. 1.

Linear array Genotyping test performed individually with different L1 gBlocks (double stranded genomic blocks). The gBlocks were designed from HPV genotypes 102 (a), 114 (b), 86 (c) and 87 (d) and taken as template for the LA test

Next-generation sequencing of HPV83 and HPV84 positive samples

From a total of 535 cervical samples genotyped by LA, 16 were HPV83+ (3.0%) and 35 were HPV84+ (6.5%). As HPV83 and HPV84 probes in LA strips cross-hybridize with L1 gBlocks from other genotypes, we selected 14 HPV83+ (S9, S27-S39) and 26 HPV84+ (S1-S26) samples (based on their strong hybridization band in the LA strips) to be genotyped by NGS individually. As depicted in Table 1, HPV genotyping by NGS showed that from the 26 cervical samples LA HPV84+, 17 were truly HPV84+ (65.4%), 5 were HPV114+ (19.2%), and 1 was HPV86+ (3.8%). Additionally, 2 samples were positive to both HPV 87 and 114, and finally 1 was HPV 84, 87 and 114 positive. HPV87 was found in the three cases in coinfection with HPV114. Concerning the 14 cervical samples LA HPV83+, 8 were truly HPV83+ (57.1%), 5 were HPV102+ (35.7%) and 1 was positive to both genotypes (Table 2).

Table 1.

HPV genotyping by NGS of 26 cervical samples LA HPV84+

| Sample Number | Linear Array | NGS |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | 39, 51, 56, 58, 62, 84 | 39, 51, 58, 62, 84 |

| S2 | 45, 59, 66, 73, 84, 89 | 45, 59, 66, 73, 89, 114 |

| S3 | 6, 53, 61, 84, 89 | 6, 53, 61, 84, 89 |

| S4 | 16, 42, 45, 54, 84 | 16, 69, 84 |

| S5 | 31, 56, 66, 82, 84 | 56, 84 |

| S6 | 58, 81, 82, 84, 89 | 16, 44, 53, 58, 66, 72, 81, 82, 84, 89 |

| S7 | 11, 42, 61, 84 | 11, 61, 114 |

| S8 | 16, 51, 54, 84 | 16, 54, 84 |

| S9 | 16, 53, 83, 84 | 16, 53, 62, 83, 114 |

| S10 | 16, 61, 84, 89 | 16, 61, 83, 84, 89 |

| S11 | 35, 66, 84, 89 | 32, 35, 66, 84, 89 |

| S12 | 39, 54, 61, 84 | 39, 51, 54, 58, 61, 62, 84, 87, 106, 114 |

| S13 | 39, 61, 84, 89 | 61, 89, 87, 114 |

| S14 | 56, 66, 70, 84 | 16, 66, 70, 87, 114 |

| S15 | 69, 71, 81, 84 | 69, 71, 81, 114 |

| S16 | 11, 39, 84 | 11, 39, 114 |

| S17 | 45, 62, 84 | 45, 62, 84 |

| S18 | 56, 61, 84 | 6, 56, 61, 68, 84 |

| S19 | 16, 84 | 16, 70, 81, 83, 86 |

| S20 | 18, 84 | 18, 84 |

| S21 | 31, 84 | 31, 83, 84 |

| S22 | 31, 84 | 31, 54, 84 |

| S23 | 45, 84 | 45, 84 |

| S24 | 45, 84 | 45, 66, 84 |

| S25 | 59, 84 | 59, 84 |

| S26 | 66, 84 | 66, 84 |

The first column shows LA results and the second column NGS results. HPV84, 86, 87 and 114 are darkened for an easier visualization

Table 2.

HPV genotyping by NGS of 14 cervical samples LA HPV83+

| Sample Number | Linear Array | NGS |

|---|---|---|

| S27 | 16, 42, 58, 62, 81, 83 | 16, 58, 81, 83 |

| S28 | 51, 54, 58, 66, 83, 89 | 58, 66, 83, 89 |

| S29 | 11, 52, 59, 62, 83 | 11, 52, 59, 62, 83 |

| S30 | 35, 54, 70, 83, 89 | 35, 54, 70, 89, 102 |

| S31 | 54, 55, 61, 83, 89 | 61, 89, 102 |

| S32 | 11, 62, 70, 83 | 16, 61, 62, 70, 83, 89 |

| S9 | 16, 53, 83, 84 | 16, 53, 83, 114 |

| S33 | 31, 62, 72, 83 | 31, 72, 102 |

| S34 | 45, 59, 64, 83 | 52, 56, 59, 61, 71, 74, 102 |

| S35 | 52, 61, 71, 83 | 52, 61, 71, 56, 74, 102 |

| S36 | 31, 61, 83 | 31, 61, 83 |

| S37 | 52, 81, 83 | 52, 81, 83 |

| S38 | 51, 83 | 51, 61, 83, 102 |

| S39 | 83 | 83, 81 |

The first column shows LA results and the second column NGS results. HPV83 and 102 are darkened for an easier visualization

L1 gene mutations from HPV83, 84, 87, 102 and 114

After comparing the sequences obtained by NGS with the L1 reference genes (downloaded from PaVE database), nucleotide variations in L1 fragment from HPV genotypes 83, 84, 87, 102 and 114 were determined. Concerning HPV83-L1, only sample S27 contained an L1 gene fragment identical to the reference, and rest of the samples showed diverse synonymous mutations. The most common nucleotide changes were c.1200A>G (in 6 samples), c.1191A>G (in 5 samples), c.1227G>C (in 5 samples), and c.1008A>G (in 4 samples) (Table 3). Regarding HPV84-L1, seventeen out of eighteen samples showed one or more nucleotide changes, being the non-synonymous mutation c.1323C>A (p.D441E) the most prevalent one (in 16 samples). Another HPV84-L1 non-synonymous mutation was detected in only one sample: c.1055A>C (p.N352T) (Table 4). Additionally, two L1 synonymous mutations were found in the three HPV87+ samples: c.1056T>C and c.1359A>G. About HPV102-L1 nucleotide changes, three out of the six positive samples (S30, S34 and S35) showed c.1362A>G mutation in their L1 sequence and only S30 sample showed the non-synonymous mutation c.1060G>A (p.G354S). Among the eight HPV114+ samples, nine mutations were detected, three of them present in all the HPV114-L1 sequences: c.1318C>G (p.P440A), c.1332A>G and c.1359C>T. Furthermore, two non-synonymous mutations were found in four samples: c.1297T>A (p.S433T) and c.1331C>A (p.T444K) (Table 5). Finally, no HPV86-L1 mutations were detected.

Table 3.

Nucleotide changes identified in HPV83-L1 when compared to the reference sequence (AF151983) in nine HPV83+ samples

| Sample number | c.1008 A > G |

c.1104 A > C |

c.1152 G > T |

c.1170 A > C |

c.1191 A > G |

c.1200 A > G |

c.1227 G > C |

c.1227 G > A |

c.1233 C > T |

c.1264 C > T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| S27 | ||||||||||

| S28 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| S29 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| S32 | ● | ● | ||||||||

| S36 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| S37 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| S38 | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| S39 | ● | ● | ● | ● |

Table 4.

Nucleotide changes identified in HPV84-L1 when compared to the reference sequence (AF293960) in eighteen HPV84+ samples

| Sample number | c.1011 A > G |

c.1055 A > Ca |

c.1173 C > A |

c.1323 C > Aa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | ● | |||

| S3 | ● | |||

| S4 | ||||

| S5 | ● | |||

| S6 | ● | |||

| S8 | ● | |||

| S10 | ● | |||

| S11 | ● | |||

| S12 | ● | |||

| S17 | ● | |||

| S18 | ● | ● | ||

| S20 | ● | ● | ||

| S21 | ● | |||

| S22 | ● | |||

| S23 | ● | |||

| S24 | ● | |||

| S25 | ● | ● | ||

| S26 | ● | ● |

anon-synonymous nucleotide changes

Table 5.

Nucleotide changes identified in HPV114-L1 when compared to the reference sequence (GQ244463) in eight HPV114+ samples

| Sample number | c.1059 C > T |

c.1167 A > C |

c.1297 T > Aa |

c.1299 C > A |

c.1305 G > A |

c.1318 C > Ga |

c.1331 C > Aa |

c.1332 A > G |

c.1359 C > T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| S7 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| S9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| S12 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| S13 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| S14 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| S15 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| S16 | ● | ● | ● |

anon-synonymous nucleotide changes

To visualize the relationship between the reference alpha-3 HPV genotypes and those obtained from the Mexican cervical samples (HPV83, 84, 86, 87, 102, 114), a phylogenetic tree was built based on their L1 gene sequences (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on alpha-3 HPVs L1 sequences. The analysis involved the 11 reference HPVs from alpha-3 species (REF) and 39 L1 sequences from HPVs 83, 84, 86, 87, 102 and 114 that infect Mexican woman. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site

Discussion

During the last decade, cytology-based screening is being replaced with HPV genotyping; Linear Array genotyping test is commonly used in many laboratories for HPV detection [8, 16]. LA test, launched in 2006, is a PCR-based strategy with pooled primer sets, coupled to hybridization to specific probes for 37 anogenital HPV genotypes immobilized on a nylon strip [7]. This test has the most abundant data in peer-reviewed literature classifying it as one of the most frequently used [17]. Undoubtedly, LA is a sensitive test of great value for epidemiological studies and HPV genotyping, but more sensitive, specific and accurate methods such as NGS allow the identification of not only a broader spectrum of HPVs, but also subtypes and variants [18–20].

HPV84 was characterized as a novel genotype in 2001 by M. Terai and R. D. Burk (accession number AF293960) from a cervicovaginal sample obtained from a 21-year-old Caucasian female with a normal Pap smear [21]. It is considered as a LR-HPV and is among the most prevalent LR-HPVs found worldwide in cervical samples [22–30]. Both HPV83 and HPV84 belong to the Alphapapillomavirus genus, species 3 group (alpha-3) together with HPV 61, 62, 72, 81, 86, 87, 89, 102 and 114. From these genotypes, only 102 and 114 were characterized after LA test was launched [31, 32], and are obviously not included in the test, neither do HPV86 and HPV87.

In the present study, non-specific hybridization of four alpha-3 HPVs in the LA test, the golden test used to detect HPVs in a patient’s sample, is being reported. Indeed, HPV102-L1 cross-reacts with the probe that detects HPV83, and likewise, HPV genotypes 86, 87 and 114 cross-react with the probe that detects HPV84. These results explain the observations in a previous study where we reported that not all HPV genotypes detected in some cervical samples with LA test were confirmed by NGS (like HPV83 and HPV84), whereas five HPVs not included in LA were detected by NGS (HPVs 32, 44, 74, 102 and 114) [9]. With the current study, we reveal that what happened in the previous work was that positivity to HPV83 and HPV84 in the LA test was only true in the 57.1% and 65.4% of the cases, respectively. In addition, as LA test is sometimes showing positivity to HPVs 83 and 84 when they are not present in the sample, the prevalence of these genotypes could be overrated, as discussed later. Moreover, we cannot dismiss the possibility that more HPV genotypes from other species could also cross-react with some of the probes in the LA strip. An already reported limitation of LA is that additional testing is necessary to detect the HR-HPV52 when HPVs 33, 35 and/or 58 are present in the sample [33]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report proving a cross-hybridization in LA test.

In this work, HPV genotyping by NGS of HPV84 positive samples (detected by LA), revealed that 69.2% of the samples were truly HPV84+, while 30.8% were HPV114+, 3.8% were HPV86+ and 11.5% were HPV87+. It is important to mention that some samples were coinfected with more than one of these genotypes. On the other hand, among HPV83+ samples with LA, 64.3% were confirmed as HPV83+ with NGS, while 42.9% were HPV102+. A recent publication shows that the clinical performance of the LA test within the VALGENT-3 framework, which is designed for comprehensive comparison and clinical validation of HPV tests, is accurate for primary cervical cancer screening [34]. Nevertheless, another recent genotyping study that compares ion torrent-next generation sequencing vs. linear array to detect anal HPVs in individual clinical specimens shows that the NGS assay detects 10 HPV genotypes that are not among the ones detected in LA test: 30, 32, 43, 44, 74, 86, 87, 90, 91, 114 [35]. Some of these HPVs could be cross-reacting with LA test as we demonstrated in this work.

New HPV genotyping tests must be developed in the upcoming years since an increasing number of genotypes are being described by using NGS platform, and their prevalence and role in cervical lesion progression needs to be assessed. Indeed, 105 putative new papillomavirus types have been identified by using a novel protocol based on improved PCR protocols combined with NGS [36]. Moreover, HPV coinfections could be hiding essential information on cervical lesion progression and more meticulous studies on multiple infections are also necessary in the near future for understanding the link between coinfections and carcinogenesis. Furthermore, FAP primers based sequencing is sensitive and effective for detection of cutaneous HPVs and its use in cervical samples could contribute to a broader knowledge on HPV infections in cervical mucosa [37–39].

The L1 gene is used for the classification of HPV genotypes as it is well conserved among all of them. HPV genotypes share between 71 and 89% of nucleotide identity, and within the same HPV type, HPV variants can be described [40, 41]. After HPV genotyping by NGS, new nucleotide changes in PGMY amplified L1 sequence have been described in this work for HPV genotypes 83, 84, 87, 102 and 114. From all the nucleotide changes reported here, HPV84-L1, HPV102-L1 and HPV114-L1 have two, one and three non-synonymous mutations, respectively. To our knowledge, there is only one study that also describes one of the nucleotide changes reported in this work: c.1323C>A in HPV84-L1 [42]. Further functional analysis should be done to understand the biological significance of the amino acid changes.

Conclusions

This study showed that HPV genotypes 86, 87 and 114 cross-hybridize with HPV84 in LA test and that HPV102 cross-reacts with HPV83 probe; these observations were confirmed by comparing LA genotyping with NGS data. Therefore, there is an over estimation of HPV 83 and 84 prevalence when HPV genotyping is performed with LA. On the other hand, it would be important to determine the prevalence and role in carcinogenesis of HPVs 86, 87, 102 and 114. Novel nucleotide changes in L1 gene from HPVs 83, 84, 87, 102 and 114 were determined in Mexican cervical samples, some of them lead to changes in the protein sequence. The biological significance of those changes should be determined in the near future. There is no doubt that more specific and sensitive tests to detect a broader spectrum of HPV genotypes should be implemented in the clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación en Salud – IMSS, grants numbers FIS/IMSS/PROT/PRIO/14/033 to AA-L and FIS/IMSS/PROT/PRIO/15/046 to LFJ-S.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive Repository with accession number SRP130362 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRP130362).

Abbreviations

- CC

Cervical Cancer

- gBlocks

Genomic Blocks

- HPV

Human Papilloma Virus

- HR-HPV

High Risk HPV

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- ICTV

International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses

- LA

Linear Array

- LR-HPV

Low Risk HPV

- NGS

Next-Generation Sequencing

- PaVE

Papillomavirus Episteme

Authors’ contributions

CA-I carried out the gBlocks design, PCR amplifications and draft the manuscript; LPL-T and VV-R were involved in patient interviews and sample recruitment; VV-R, CS-R and RM-T conducted the Linear Array HPV genotyping test; MGF-M and DO performed PCRs and the NGS assays; CA-I, MGF-M and DO realized the bioinformatics analyses; AA-L and LFJ-S conceived of and designed the study, supervised the performed experiments and analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocols were approved by the National Committee on Health Research and Ethics of the IMSS (with the registration numbers R-2012-785-090 and R-2014-785-036).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cristina Artaza-Irigaray, Email: chispuncris@hotmail.com.

María Guadalupe Flores-Miramontes, Email: nereyda_2404@hotmail.com.

Dominik Olszewski, Email: dominik.ol190592@gmail.com.

Verónica Vallejo-Ruiz, Email: veronica_vallejo@yahoo.com.

Laura Patricia Limón-Toledo, Email: patricialimontoledo@gmail.com.

Cibeles Sánchez-Roque, Email: ciboneyroque@gmail.com.

Rocío Mayoral-Torres, Email: rosi-2408@outlook.es.

Luis Felipe Jave-Suárez, Phone: +521 (33) 36 17 00 60, Email: lfjave@yahoo.com.

Adriana Aguilar-Lemarroy, Phone: +521 (33) 36 17 00 60, Email: adry.aguilar.lemarroy@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25(S1):2–23. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bravo IG, Félez-Sánchez M. Papillomaviruses Viral evolution, cancer and evolutionary medicine. Evolution, medicine, and public health. 2015;2015(1):32–51. doi: 10.1093/emph/eov003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard H-U, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, zur Hausen H, de Villiers E-M. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffman M, Doorbar J, Wentzensen N, De Sanjosé S, Fakhry C, Monk BJ, et al. Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2016;2:16086. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Franceschi S, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(10):2349–2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinau M, Onyekwuluje JM, Scarbrough MZ, Unger ER, Dillner J, Zhou T. Performance of commercial reverse line blot assays for human papillomavirus genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(5):1539–1544. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06576-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens MP, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN. Human papillomavirus genotyping using a modified linear array detection protocol. J Virol Methods. 2006;135(1):124–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutlée F, Rouleau D, Petignat P, Ghattas G, Kornegay JR, Schlag P, et al. Enhanced detection and typing of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in anogenital samples with PGMY primers and the linear array HPV genotyping test. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):1998–2006. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00104-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores-Miramontes MG, Torres-Reyes LA, Alvarado-Ruíz L, Romero-Martínez SA, Ramírez-Rodríguez V, Balderas-Peña LM, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping by linear Array and next-generation sequencing in cervical samples from Western Mexico. Virol J. 2015;12(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artaza-Irigaray C, Flores-Miramontes MG, Olszewski D, Magana-Torres MT, Lopez-Cardona MG, Leal-Herrera YA, et al. Genetic variability in E6, E7 and L1 genes of human papillomavirus 62 and its prevalence in Mexico. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12:15. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravitt P, Peyton C, Alessi T, Wheeler C, Coutlee F, Hildesheim A, et al. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(1):357–361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.357-361.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babraham Bioinformatics. Fast QC.: Babraham Bioinformatics. Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed Jan 2018.

- 13.Van Doorslaer K, Tan Q, Xirasagar S, Bandaru S, Gopalan V, Mohamoud Y, et al. The papillomavirus episteme: a central resource for papillomavirus sequence data and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41(D1):D571–D5D8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10(3):512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambulos NP, Jr, Schumaker LM, Mathias TJ, White R, Troyer J, Wells D, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based HPV genotyping assay validated in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded oropharyngeal and cervical cancer specimens. Journal of biomolecular techniques: JBT. 2016;27(2):46. doi: 10.7171/jbt.16-2702-004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poljak M, Cuzick J, Kocjan BJ, Iftner T, Dillner J, Arbyn M. Nucleic acid tests for the detection of alpha human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 2012;30:F100–F1F6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barzon L, Militello V, Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Peta E, Squarzon L, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping by 454 next generation sequencing technology. J Clin Virol. 2011;52(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Militello V., Lavezzo E., Costanzi G., Franchin E., Di Camillo B., Toppo S., Palù G., Barzon L. Accurate human papillomavirus genotyping by 454 pyrosequencing. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2013;19(10):E428–E434. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arroyo LS, Smelov V, Bzhalava D, Eklund C, Hultin E, Dillner J. Next generation sequencing for human papillomavirus genotyping. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(2):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terai M, Burk RD. Complete nucleotide sequence and analysis of a novel human papillomavirus (HPV 84) genome cloned by an overlapping PCR method. Virology. 2001;279(1):109–115. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aguilar-Lemarroy A, Vallejo-Ruiz V, Cortés-Gutiérrez EI, Salgado-Bernabé ME, Ramos-González NP, Ortega-Cervantes L, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in Mexican women with normal cytology, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer: type-specific prevalence and HPV coinfections. J Med Virol. 2015;87(5):871–884. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, Flores R, Salmeron J, Lee J-H, et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2008;17(8):2036–2043. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menzo S, Ciavattini A, Bagnarelli P, Marinelli K, Sisti S, Clementi M. Molecular epidemiology and pathogenic potential of underdiagnosed human papillomavirus types. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8(1):112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaltout MF, Sallam HN, AbouSeeda M, Moiety F, Hemeda H, Ibrahim A, et al. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus among women older than 18 years in Egypt: a multicenter, observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filipi K, Tedeschini A, Paolini F, Celicu S, Morici S, Kota M, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection and genotype prevalence among albanian women: a cross-sectional study. J Med Virol. 2010;82(7):1192–1196. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammatuna P, Giovannelli L, Matranga D, Ciriminna S, Perino A. Prevalence of genital human papilloma virus infection and genotypes among young women in Sicily, South Italy. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2008;17(8):2002–2006. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreccio C, Corvalán A, Margozzini P, Viviani P, González C, Aguilera X, et al. Baseline assessment of prevalence and geographical distribution of HPV types in Chile using self-collected vaginal samples. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi Y-D, Jung W-W, Nam J-H, Choi H-S, Park C-S. Detection of HPV genotypes in cervical lesions by the HPV DNA Chip and sequencing. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98(3):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Datta P, Bhatla N, Dar L, Patro AR, Gulati A, Kriplani A, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection among young women in North India. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34(2):157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Burk RD. Identification and characterization of two novel human papillomaviruses (HPVs) by overlapping PCR: HPV102 and HPV106. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(11):2952–2955. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83178-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ekström J, Forslund O, Dillner J. Three novel papillomaviruses (HPV109, HPV112 and HPV114) and their presence in cutaneous and mucosal samples. Virology. 2010;397(2):331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oštrbenk A, Kocjan BJ, Poljak M. Specificity of the linear Array HPV genotyping test for detecting human papillomavirus genotype 52 (HPV-52) Acta Dermatovenerol. 2014;23:53–56. doi: 10.15570/actaapa.2014.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Oštrbenk A, Poljak M, Arbyn M. Assessment of the Roche linear Array HPV genotyping test within the VALGENT framework. J Clin Virol. 2018;98:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowak RG, Ambulos NP, Schumaker LM, Mathias TJ, White RA, Troyer J, et al. Genotyping of high-risk anal human papillomavirus (HPV): ion torrent-next generation sequencing vs. linear array. Virol J. 2017;14(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0771-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brancaccio RN, Robitaille A, Dutta S, Cuenin C, Santare D, Skenders G, et al. Generation of a novel next-generation sequencing-based method for the isolation of new human papillomavirus types. Virology. 2018;520:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forslund O, Johansson H, Madsen KG, Kofoed K. The nasal mucosa contains a large spectrum of human papillomavirus types from the Betapapillomavirus and Gammapapillomavirus genera. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(8):1335–1341. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Pan Y, Xu Z, Wang Q, Hang D, Shen N, et al. Improved detection of human papillomavirus harbored in healthy skin with FAP6085/64 primers. J Virol Methods. 2013;193(2):633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forslund O, Antonsson A, Nordin P, Stenquist B, Hansson BG. A broad range of human papillomavirus types detected with a general PCR method suitable for analysis of cutaneous tumours and normal skin. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(9):2437–2443. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-9-2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Villiers E-M, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard H-U, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burk RD, Harari A, Chen Z. Human papillomavirus genome variants. Virology. 2013;445(1):232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang B-C, Wang X-L, Xue F-X, Liu H-T. Analysis of human papillomavirus type 61, 83 and 84 MY fragments and preparation of standard samples. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2010;24(2):107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive Repository with accession number SRP130362 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRP130362).