Abstract

E-waste being hazardous in nature demands scientific management thereby protecting and safeguarding the health of the workers. A major chunk of e-waste ends up in informal sectors where crude methods are employed thereby risking the health of workers. The current scoping review, Based on Arksey and O'Malley's framework was done to explore the available literature to summarize the perceived and manifested health problems among informal e-waste workers. A literature search was done in three databases namely PubMed, Web of Science and ScienceDirect between 1/01/2010 and 1/01/2018. All the titles and abstracts were scrutinized to include only those studies on the basis of health symptoms/problems among workers. Health problems, thus explored, were categorized into five broad categories- physical injuries, respiratory, skin, musculoskeletal, and other general health problems. Major factors which could be related to health problems were job designation, age, non-usage of personal protective equipment, exposure to dust, and hazardous chemicals.

Keywords: E-waste, health, informal sector, workers

INTRODUCTION

Electronic waste (e-waste) consists of discarded electrical or electronic equipment, for example, laptops, computers, mobile phones, televisions, DVD players, mp3 players, and so on, by their users when they realize it is no longer useful or reached the end of their life.[1] It is one of the fastest growing waste streams in the world.[2] Along with precious and rare metals such as gold, copper, nickel, neodymium, dysprosium, praseodymium, and so on;[3] it also comprises of harmful substances including lead, mercury, hexavalent chromium, and brominated flame retardants (BFRs).[4] The presence of these harmful substances makes e-waste hazardous in nature.[5] In addition to the hazardous components, on processing, e-waste releases toxic by-products such as dioxin.[4] Hence, to contain the damage to both human and environmental health, Basel Convention (2002) emphasized environmentally sound management of e-waste.[5] However, the reality is different.

Globally, 44.7 Million tons (Mt) of e-waste was discarded domestically in 2016, out of which, only 8.9 Mt (20%) was reported to be treated formally. There is no documentation of the remaining 80%.[6] The extraction of precious metals from e-waste and its processed materials is more economical and energy saving than from direct mining.[7] This makes e-waste recycling lucrative in nature. However, the cost which is incurred while recovering the metal deters its formal treatment, paving its way to informal sectors.[8] Informal e-waste sector has become an important source of livelihood for thousands of urban poor in developing and emerging Asian and African countries. It is estimated that this sector employs approximately two-fifty hundred people in Delhi, India.[7] Workforce predominantly comprises of the marginalized population (ethnic or religious minorities) and migrants. Women and children constitute a significant portion of the workforce.[8] Workers use rudimentary techniques to recover precious metals which pose threat to their health.[7] Poverty, lack of alternative employment opportunities, and little or no formal education compel thousands to forgo their health and choose this readily available hazardous employment for livelihood.[9,10,11]

A large number of environmental epidemiological studies have measured exposure (heavy metals and chemicals) among informal e-waste workers using direct exposure measurement techniques such as biological sampling (blood sample, urine sample, the hair sample, and so on).[12,13,14,15] The only existing systematic review which has summarized the health consequences has conceptualized them as biological disturbances (disturbance in thyroid hormone functioning, micronuclei in binucleated cells, DNA damage, and so on) of faulty exposure (chromium, lead, cadmium, BFRs, and so on) and neglected the perceived and manifested health problems of the workers.[16] It is important to have an idea about the nature of health problems faced by the workers to develop need based preventive strategies.

The present scoping review attempts to explore the available literature to summarize the perceived and manifested health problems among e-waste workers employed in the informal sector. The researcher also aimed to explore the factors influencing the health of workers from the selected studies.

METHODS

The protocol of this scoping review is from the framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley. The scoping review accounts for the diversity of relevant literature and studies using different methodologies, which is not feasible in a traditional review. It consists of five stages: (i) Identifying the research question; (ii) Identifying relevant studies; (iii) Study selection; (iv) Charting the data; (v) Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.[17] The review was carried over the period of 1 month (21st August 2018 to 21st September 2018)

Identifying the research question

What is known from the existing literature about the perceived and manifested health problems among e-waste workers employed in informal sectors?

Identifying relevant studies

Search resources

A comprehensive search including several sources of literature, including electronic databases, reference lists of relevant literature, and varying sources of conference proceedings were conducted. This scoping review was approached in the following steps:

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, and Science Direct databases were conducted using keywords described in Table 1.

The reference lists of all included papers were manually checked to find additional relevant studies.

A separate general search was carried out in Google to get any other relevant study.

Table 1.

Keywords for searching relevant studies

| Database | Keywords | Customization | Items found |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND informal AND recycling (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND recycling |

Timeframe: 1/01/2010 to 1/01/2018Language: English | 181 |

| Web of Science | (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND informal AND recycling (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND recycling |

Timeframe: 1/01/2010 to 1/01/2018Language: EnglishFields-3 fields | 45 |

| Science Direct | (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND informal AND recycling (“e-waste” OR “*WEEE” OR “electronic waste”) AND workers AND health AND problems AND recycling |

Timeframe: 1/01/2010 to 1/01/2018Language: EnglishAll article typePublication Title (Waste Management, Environmental Pollution, Journal of Hazardous Material | 231 |

| Total | 457 |

*WEEE-Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

Search strings

The following keywords [Table 1] were used for searching the relevant studies. Because of the broadness of search terms, many irrelevant studies appeared that subsequently got eliminated. Similar sets of keywords were used in all the databases with customization as required. The detail is mentioned in Table 1:

Study selection

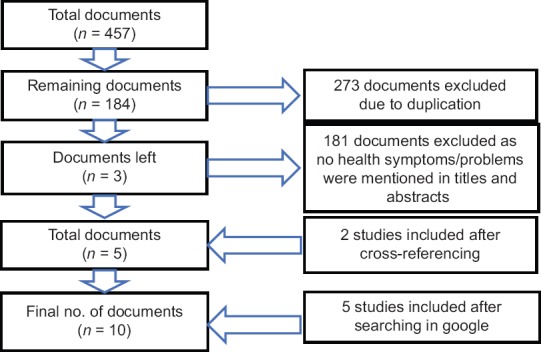

All the documents, obtained after using the above-mentioned keywords, were saved in Zotero, and the duplicates were removed. Zotero is a referencing software and also can be used for removing duplicates. The process of selection of studies is explained in Figure 1

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of studies for the scoping review

Data extraction

The process of data extraction in scoping review is called as “charting,” which consists of a descriptive summary of selected studies. The data charting form, consisting of a mixture of general as well as specific information about the study, was prepared by the researcher. The following information was recorded: Author (s) with the year of publication, discipline, study setting, objectives, study type/design, sampling technique, study samples, age of participants, sample size, exposure measure, outcome assessment, and outcomes.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

This review could bring out the perceived and manifested health problems among the informal e-waste handlers. The results of ten studies have been summarized in this section [Table 2]. School of Public Health was involved in the majority (6) of the studies.[11,18,19,20,21,22] Majority of the studies (7) were conducted in Ghana[11,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] followed by two in India[10,25] and one in Nigeria.[22] Among the selected ten studies, Five were quantitative studies,[18,20,21,22,25] three were qualitative,[10,11,19] one mixed-methods,[23] and one exploratory study.[24] All the quantitative studies were cross-sectional in nature and had either assessed or analyzed health problems among e-waste workers as their major objective,[18,20,21,22,25] whereas the other studies had different objectives. Only a few studies employed random sampling techniques (multistage) to sample the participants.[22,23] Only male workers formed the sampled population in the majority of the studies.[11,19,20,21,24,25] Although few studies consisted of both male and female workers, the proportion of female workers in all those studies was almost negligible.[18,22,23] The sampled population were predominantly of younger age group i.e. between 15 and 30 years of age.[18,20,22,23,25] The perceived and manifested health problems that appeared in the existing literature were categorized under five broad headings-physical injuries, respiratory problems, skin problems, musculoskeletal problems, and other general problems [Table 3]. The various factors which were highlighted in the studies have been summarized in Table 3. Only one quantitative study used a semi-structured survey to explore the factors that may be associated with health problems among informal e-waste handlers,[22] whereas the remaining studies employed techniques such as physical examination, biological sampling, monitoring exposure, and recording activity in log book singly or in combination along with the survey.[18,20,21,25] In-depth, interviews and field notes were most common techniques in qualitative studies[11,19] followed by unstructured interviews and checking medical records to explore the factors.[10] The only mixed method study conducted, employed survey, Focus Group Discussion, in-depth interview and observation as data collection techniques.[23] The exploratory study, utilized biological sampling and screening as data collection techniques.[24] Workers' reported health outcomes were the only reliable outcome measures in half of the studies.[11,19,21,22,23]

Table 2.

Summary of the selected studies

| Authors | Discipline | Study setting | Objectives | Study type/design | Sampling technique | Study samples | Age | Sample size | Exposure measures | Outcome assessment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caranavos et al., 2013[18] | Public Health | Ghana | Assess health symptoms and chemical markers of exposure | Quantitative | Non-random but representative | Both males and females | 15-73 years (51.7% between 15-30 years) |

174 | SurveyScreening Biological sampling |

Workers reported Clinician-reportedBiological sampling report |

Health problems |

| Akormedi, Fobil and Asampong, 2013[19] | Public Health | Ghana | Investigate and describe informal e-waste recycling and working conditions | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Males | 13-34 years (the majority in the 20s) |

20 | In-depth interview Field notes |

Workers reported | Process of e-waste recycling Working conditions |

| Pandey and Govind, 2014[10] | Social Science | India | Explore the working conditions of the e-waste recyclers and to see whether they were using any safety equipment while doing the dismantling or processing works | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | 30 | Unstructured interview with workers and doctors Government reports |

Workers reported Clinician-reported Medical records reported |

Working conditions Health problems |

| Amankwaa, 2014[23] | Department of Geography and Resource Development | Ghana | Evaluate the relationship among livelihood, environment, and health | Mixed-methods | Multi-stage cluster | Both males and females | 73% between 15-30 years | 140 | Survey Observation Focus Group Discussion In-depth interviews |

Workers reported | Health problems |

| Adusei, 2015[20] | Public Health | Ghana | Analysis of health conditions associated with different e-waste activities at different activity spaces | Quantitative | Convenient | Males | <20 to>40 years (74% <30 years) |

112 | Survey Physical examination |

Workers reported Clinician-reported |

Health conditions |

| Asampong et al., 2015[11] | Public Health | Ghana | Describing health-seeking behavior, and social and other factors affecting this behavior, among electronic waste workers | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Males | 18-32 years | 20 | In-depth interview Field notes |

Workers reported | Health seeking behavior |

| Burns et al., 2016[21] | Public Health | Ghana | Examine the association between occupational noise exposures and heart rates over a short period (1 day) Evaluate the potential influence of work activities and perceived stress on the observed relationship between occupational noise exposures and heart rates over a short period |

Quantitative | Not mentioned | Males | 18-34 years (average age) | 57 | Survey Measurement of noise exposure and heart rate using equipment Activity log book |

Workers reported | Health problems |

| Carlson, 2016[24] | Not mentioned | Ghana | Investigate e-waste worker exposures to heavy metals, nutrient metals, and loud noise | Not mentioned explicitly | Not mentioned | Males | The average age of 26 years | 56 | SurveyHearing screening Blood sampling |

Workers reported Clinician-reported Blood sampling report |

Health problem |

| Ohajinwa et al., 2017[22] | Public Health | Nigeria | Assess the prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with occupational injury for e-waste workers in the informal sector | Quantitative study | Multistage | Both males and females | 21-39 years (57% <30 years) |

279 | Semi-structured survey | Workers reported | Health problems |

| Sharma et al., 2017[25] | Community Medicine | India | Assess the health problems among e-waste handlers | Quantitative study | Not mentioned | Males | 18 to >50 years (53% <30 years) | 250 | Survey Physical examination Medical record |

Workers reported Clinician-reported Medical records reported |

Health problems |

Table 3.

Perceived and Manifested Health Problems along with the factors

| Health Problems | Factors |

|---|---|

| Physical injuries[10,11,18-20,22] | Non-usage of personal protective equipment by most of the workers[10,18-20,22] Long working hours[10,19,20] Work space[20] Job designation[11,20,22] Age and geographical location[22] Lack of knowledge[18] |

| Respiratory problems[10,11,18,21,25] | Lack of knowledge[18] Lack of ventilation[10] Exposure to dust and hazardous chemicals[10,11,18] |

| Skin problems[10,18,20] | Lack of knowledge[18] Job designation[20] Exposure to dust and hazardous chemicals[10,20] |

| Musculoskeletal problems[11,18,22,25] | Lack of knowledge[18] Sustained posture[11] |

| Other general health problems[10,11,18,21,23-25] | Lack of knowledge[18,23] Not using hearing protection device[21] Unfavorable physical conditions at workplace[21] |

Physical injuries

Cross-sectional studies conducted in Ghana and Nigeria reported that 96% and 59.5% of all the e-waste workers had cuts respectively.[20,22] Workers in all the three qualitative studies conducted in Ghana and India reported that cuts were the most common injuries they encountered along with burns.[10,11,19] Electric shocks (14%)[22] and eye injury (5.7%)[18] were also reported.

Respiratory problems

Three studies from Ghana reported that workers faced different types of respiratory problems such difficulty in breathing was reported by 15.8% of the workers,[21] cough was reported by 4.6% of the workers,[18] chest pain,[11] and 4.6% of workers reported other respiratory problems.[18] Cough was also reported by the workers in an ethnographic study conducted in Delhi, India.[10] One Nigerian study also highlighted that 5% of workers were suffering from chest pain.[22] Cough with sputum appeared to be an important finding among workers in a quantitative study in Delhi, India.[25]

Skin problems

A result of clinical examination among the workers in a study in Ghana highlighted that 47.2% of the study participants had various skin abnormalities with fungal rashes being the most common among them (25.3%). In the same study, 4.6% of the workers reported that they had itching/rashes.[18] Workers also reported skin irritation in a qualitative study conducted in Delhi, India.[10] A clinical assessment of workers in a study in Ghana also found various skin problems among workers with scars being the most common among them.[20]

Musculoskeletal problems

General body pain was reported to be a prominent health problem among the studies.[11,18,22,25] Further, Nigerian study also reported that low back pain was the most common category of body pain among the participants as 29% of them had back pain in last 12 months.[22]

Other general health problems

A variety of other health problems were reported in the workers than the specific ones mentioned above.

Two studies conducted in Ghana had found difficulty in hearing among the workers. In one study, it was self-reported by 26.3% of the participants,[21] whereas it was clinically screened in the other one.[24] Overweight and obesity were clinically examined in two of the studies conducted in Ghana and India. A study from Ghana reported that 25.3% of workers were overweight and 2.3% were obese,[18] whereas 14.8% of the workers were found to be overweight and 33.2% were found to be obese.[25] Workers were also diagnosed with high blood pressure.[21,25] 40% of the workers reported an occupational accident.[23] Moderate to high level of perceived stress along with abnormal heartbeat and dizziness were self-reported.[21] Other minor problems reported in the studies were stomach ache,[10,11] headache,[11,18] nausea,[10,18] and burning eyes.[25]

Factors

Out of the five quantitative studies and one mixed-methods study, three quantitative studies tried to find the association between various factors and health problems among informal e-waste workers. Injuries were found to be significantly associated with job designation, and burns were found to be associated with the workspace.[20] Injury was also found to be significantly associated with job designation, geographical location, and age.[22] A relationship between noise exposure and heart rate was also observed.[21] The three remaining studies only listed the factors which could be related to health problems among e-waste workers.[18,23,25] All the qualitative studies attempted to explore the factors which could have affected the health of the workers.[10,11,19] Some of the other factors reported were non-usage of personal protective equipment, long working hour, job designation, and exposure to dust and hazardous materials.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this review was to summarize the perceived and manifested health problems among workers engaged in the unorganized/informal e-waste sector from the existing literature.

Studies focusing on the occupational aspect of e-waste management are majorly attempted by the researchers in the field of environmental epidemiology. A handful of studies had conducted direct exposure assessment among the workers engaged in informal e-waste recycling. They used biological samples such as blood, urine, hair, etc., to detect the presence of heavy metals.[12,13,14,15] However, these studies did not explicitly mention the perceived and manifested health problems among workers engaged in the unorganized/informal e-waste sector. Hence, the present exercise attempted to explore the same. The involvement of school of Public Health in the majority of the studies implies the increasing recognition of e-waste management as a public health problem thereby demanding further exploration. Studies selected for the current review also highlighted this same aspect. The studies were mostly conducted in Ghana, India, and Nigeria reflecting the predominance of informal e-waste management practices in developing and emerging economies which is in sync with International Labor Organization's report. This is stipulating that informal e-waste sector has become an important source of livelihood in developing and emerging Asian and African countries.[8] However, all the studies from Ghana and India were from the same sites. For instance, all the seven studies in Ghana were from Agbogbloshie, similarly both the studies from India were from East Delhi. The Nigerian study was multicentric, and the researchers found the association between outcome (occupational injury) and geographical location. This is more representative than the other studies, and thus, it demands further exploration at different settings. Although the majority of the existing studies on e-waste management were carried out in China, this review did not come across any Chinese study that specifically looked on perceived and manifested health problems among informal e-waste handlers.

Although all of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional in nature indicating that this could be the most feasible epidemiological study design for studying health problems among informal e-waste workers, cross-sectional study design is one of the weakest design to make any inference about association between exposure and outcome. These studies were carried out both with and without comparators. The comparison of health problems were done both between e-waste workers and non-e-waste workers;[18] and also between different categories of e-waste workers.[20,22] Comparison between different categories of the same occupation explains differential exposures leading to differential health problems among informal e-waste workers. The cohort study design is the ideal one to show the association between exposure and outcome, but it is difficult to carry out in this case as the latent period will be significantly long.

Few studies employed random sampling techniques (multistage) to sample the participants. The study conducted in Nigeria elaborated the multistage sampling procedure where randomness was maintained till the selection of sampling units (sampling units consisted of repairers shops, dismantling, and dump/burning sites). However, whether participants had also been selected randomly was not mention.[22] Another study conducted in Ghana also utilized multistage sampling, but the author did not describe the sampling process.[23] Other quantitative studies either did not mention anything about the sampling techniques or used non-random sampling techniques. Generalizability was the question in all other studies except the Nigerian study where researchers could statistically calculate the sample size, and hence, the results can be extrapolated to a larger population of e-waste handlers. Negligible representation of females in the studies could be indicative of inadequate sample selection strategies used in the study. A report by International Labor Organization highlighted that a sizeable number of women formed significant proportion of labor workforce in informal e-waste management sector.[8] The absence or negligible representation of women in the selected studies could have led to the underestimation of the health problems faced by them. Only few studies attempted to find the factors that may be associated with health problems among informal e-waste handlers, whereas other studies just listed them. This highlights the need of further enquiry regarding the possible factors that could be related to health problems.

Qualitative studies made use of different approaches such as grounded theory approach and ethnographic approach. Although their primary objective was not to explore the health problems among the workers, this information emerged from all the three studies. As this area is relatively unexplored, use of qualitative methods would result in better understanding of the problems such as - why do people engage in this type of hazardous occupation, what is their perception about their health problems, what are the different factors which workers feel may be contributing to the health problems, what is their working condition, and so on. These could give more clarity to the picture exemplified from the three qualitative studies used in the review. These studies highlighted, with greater detail, the health problems perceived by the workers which would be difficult to capture just by using quantitative methods.

The sampled population was predominantly of younger age group i.e. between 15 and 30 years of age. This point to the involvement of a greater representation of relatively young population in this vulnerable employment. This is further corroborated by the International Labor Organization report that has highlighted the involvement of young people in this sector. Although the report also says that children, as well as the adolescent (11-18 years), constituted an important part of this workforce, the selected studies had only adolescent as their participants, that too of age group 15 years or above. The nature of health problems experienced by the children could be vastly different than those of adults indicating the need for further research focusing on children. One of the reasons for the absence of children from the studies could be ethical constraints. Involving children in the study requires their assent along with the parental/legal guardian's consent. Children involved in this occupation, sometimes, may be orphan or they may be staying away from their family. In this case, there is a difficult choice between the principles of justice and autonomy. If you try to uphold autonomy by excluding children who have no parental consent, then you are being unjust to a group that is already subjected to rights' violation. However, if you include them without parental consent in the spirit of justice, you technically violate their autonomy.

Multiple data sources help in validation of the findings. The principle data source in all the selected studies was self-reporting, as the aim of this review was to find the perceived and manifested health problems among the informal e-waste handlers. Except Nigerian study, all other studies made use of different data sources along with self-reporting by the workers such as a study in Ghana utilized physical skin examination of workers along with survey to get more clarity about the outcome. Similarly, an ethnography conducted in India made use of physician interviews and medical records along with workers' narratives to have a broader understanding of the health problems faced by the workers. Workers' reported health outcomes were the only reliable outcome measures in half of the studies that could lead to either under or over-reporting.

CONCLUSION

This review attempted to summarize health problems among the workers working in informal e-waste management sectors. Health problems were broadly grouped under five categories, and factors that may be associated with each category were also explored from the studies. The selected studies have highlighted a broad range of health problems experienced by the e-waste workers in different settings. However, the studies had several methodological shortcomings that reduced their robustness in uncovering the full extent of health consequences along with the factors affecting them. Although quantitative methods are adequate to assess the extent of manifested health problems, qualitative exploration is inevitable to extract the perceptions of workers regarding their health problems. This suggests the need for well-planned primary research studies with appropriate mixed-methods approaches.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely acknowledge Professor TK Sundari Ravindran for her constructive comments. I am also very thankful to my colleagues Dr. Uma V Sankar, Malu Mohan and Joanna Sara Valson for their valuable inputs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinto VN. E-waste hazard: The impending challenge. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2008;12:65–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.43263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins DN, BruneDrisse M-N, Nxele T, Sly PD. E-waste: A global hazard. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80:286–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lixandru A, Venkatesan P, Jönsson C, Poenaru I, Hall B, Yang Y, et al. Identification and recovery of rare-earth permanent magnets from waste electrical and electronic equipment. Waste Manag. 2017;68:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO | Electronic waste [Internet] WHO. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ceh/risks/ewaste/en/

- 5.Ogunseitan OA. The Basel convention and e-waste: Translation of scientific uncertainty to protective policy. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e313–4. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Global E-waste Monitor 2017: Quantities, Flows, and Resources | Request PDF [Internet]. ResearchGate. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321797215_The_Global_E-waste_Monitor_2017_Quantities_Flows_and_Resources .

- 7.Awasthi AK, Li J. Management of electrical and electronic waste: A comparative evaluation of China and India. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;76:434–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundgren K. InFocus Programme on Safety and Health at Work and the Environment, International Labour Organization, Sectoral Activities Department, International Labour Organization. The global impact of e-waste: addressing the challenge [Internet] 2012. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/... ed_dialogue/... sector/documents/publication/wcms_196105.pdf .

- 9.Agyei-Mensah S, Oteng-Ababio M. Perceptions of health and environmental impacts of e-waste management in Ghana. Int J Environ Health Res. 2012;22:500–17. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2012.667795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey P, Govind M. Social repercussions of e-waste management in India: a study of three informal recycling sites in Delhi. Int J Environ Stud. 2014;71:241–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asampong E, Dwuma-Badu K, Stephens J, Srigboh R, Neitzel R, Basu N, et al. Health seeking behaviours among electronic waste workers in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1065. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2376-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q, He AM, Gao B, Chen L, Yu QZ, Guo H, et al. Increased levels of lead in the blood and frequencies of lymphocytic micronucleatedbinucleated cells among workers from an electronic-waste recycling site. J Environ Sci Health Part A. 2011;46:669–76. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2011.563176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldt T, Fobil JN, Wittsiepe J, Wilhelm M, Till H, Zoufaly A, et al. High levels of PAH-metabolites in urine of e-waste recycling workers from Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Sci Total Environ. 2014;466-467:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srigboh RK, Basu N, Stephens J, Asampong E, Perkins M, Neitzel RL, et al. Multiple elemental exposures amongst workers at the Agbogbloshie electronic waste (e-waste) site in Ghana. Chemosphere. 2016;164:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittsiepe J, Feldt T, Till H, Burchard G, Wilhelm M, Fobil JN. Pilot study on the internal exposure to heavy metals of informal-level electronic waste workers in Agbogbloshie, Accra, Ghana. Environ SciPollut Res. 2017;24:3097–107. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant K, Goldizen FC, Sly PD, Brune M-N, Neira M, Berg M van den, et al. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: A systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e350–61. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halas G, Schultz ASH, Rothney J, Goertzen L, Wener P, Katz A. A scoping review protocol to map the research foci trends in tobacco control over the last decade. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006643. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caravanos J, Clarke EE, Osei CS, Amoyaw-Osei Y. Exploratory health assessment of chemical exposures at e-waste recycling and scrapyard facility in Ghana. J Health Pollut. 2013;3:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akormedi M, Asampong E, Fobil JN. Working conditions and environmental exposures among electronic waste workers in Ghana. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2013;19:278–86. doi: 10.1179/2049396713Y.0000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adusei AA. Mapping of Health Conditions Associated with E-Waste Activities at Agbogbloshie, Accra [Internet] [MSc OCCUPATIONAL HYGIENE DEGREE] [Ghana]: University of Ghana; 2015. [cited 2018 Aug 21]. Available from: http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/handle/123456789/8089 . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns K, Sun K, Fobil J, Neitzel R. Heart rate, stress, and occupational noise exposure among electronic waste recycling workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:140. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohajinwa CM, Bodegom van PM, Vijver MG, Olumide AO, Osibanjo O, Peijnenburg WJGM. Prevalence and injury patterns among electronic waste workers in the informal sector in Nigeria. InjPrev. 2018;24:185–92. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.E-waste livelihoods, environment and health risk: Unpacking the connections in Ghana | Request PDF [Internet] ResearchGate. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306019229_E.waste_livelihoods_environment_and_health_risk_Unpacking_the_connections_in_Ghana .

- 24.Carlson K. Electronic Waste Worker Health: Studying Complex Problems in the Real World. In: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development..ICTD ’16 [Internet] Ann Arbor, MI, USA: ACM Press; 2016. [cited 2018 Sep 19]. pp. 1–4. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2909609.2909618 . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma M, Singh MM, Ingle GK, Kishore J. Health status of E-waste workers in resettlement areas of East Delhi, India. Int J Health Educ Med Inform. 2017;4:23–8. [Google Scholar]