Abstract

Motivation

Three-dimensional (3D) genome organization plays important functional roles in cells. User-friendly tools for reconstructing 3D genome models from chromosomal conformation capturing data and analyzing them are needed for the study of 3D genome organization.

Results

We built a comprehensive graphical tool (GenomeFlow) to facilitate the entire process of modeling and analysis of 3D genome organization. This process includes the mapping of Hi-C data to one-dimensional (1D) reference genomes, the generation, normalization and visualization of two-dimensional (2D) chromosomal contact maps, the reconstruction and the visualization of the 3D models of chromosome and genome, the analysis of 3D models and the integration of these models with functional genomics data. This graphical tool is the first of its kind in reconstructing, storing, analyzing and annotating 3D genome models. It can reconstruct 3D genome models from Hi-C data and visualize them in real-time. This tool also allows users to overlay gene annotation, gene expression data and genome methylation data on top of 3D genome models.

Availability and implementation

The source code and user manual: https://github.com/jianlin-cheng/GenomeFlow.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The three-dimensional genome organization is important for cellular function (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2014). Chromosome conformation capture techniques like Hi-C (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009) has enabled the study of 3D genome organization in high resolution and high throughput. Graphical tools such as Juicer (Durand et al., 2016) have been developed to process and analyze Hi-C data. Several algorithms have been proposed to reconstruct 3D genome models from Hi-C data (Segal and Bengtsson, 2015; Serra et al., 2015; Varoquaux et al., 2014). But there is no graphical tool with an easy user interface to build, analyze 3D genome models and integrate modeling with functional genomics data. To fill the gap, we built a comprehensive tool, GenomeFlow, for processing Hi-C data, reconstructing and analyzing 3D genome models, and integrating 3D models with functional genomics data.

2 Function

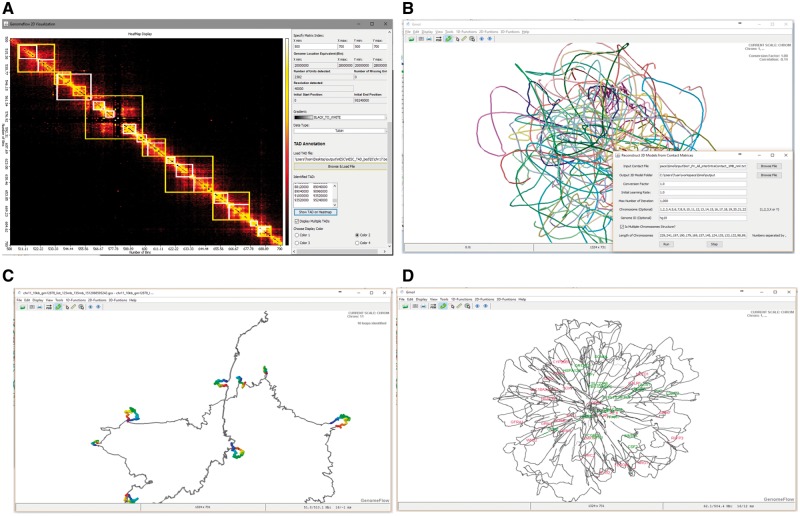

The function of GenomeFlow is organized in three categories: 1D function, 2D function and 3D function. 1D function allows users to map raw Hi-C pair-end reads to a reference genome to identify chromosomal contacts. 2D function is used to create, normalize and visualize contact matrices. 3D function is for reconstructing and analyzing 3D models. Figure 1 shows four typical 2D and 3D functional features: visualization of contact matrix and topologically associating domains (TADs), 3D model reconstruction, chromatin loop identification and model annotation. The most important function features of GenomeFlow are described below.

Fig. 1.

(A) Visualization of a contact matrix and its TADs; (B) reconstruction of a genome model in real time; (C) chromatin loops are identified and highlighted; (D) a model is annotated by two groups of genes (in red and green)

2.1 Map Hi-C reads to 1D genome sequence

GenomeFlow allows users to map raw pair-end Hi-C reads to a reference genome to generate chromosomal contacts. GenomeFlow calls external genome mapping tools such as Bowtie2 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012) to perform the indexing and mapping operations. It stores the mapped data file in a text file format, which can be used by the 2D function to generate contact matrices. This 1D function is optional since users can load their already mapped reads files into GenomeFlow for 2D and 3D analysis.

2.2 Conversion of mapped reads to 2D contact matrices

GenomeFlow provides a function to convert a mapped Hi-C reads file from the text format into a compressed file containing chromosomal contact matrices in the binary hic format (Durand et al., 2016). The function normalizes chromosomal contacts with Knight-Ruiz matrix balancing normalization (Rao et al., 2014) and Vanilla-Coverage normalization (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009). It also provides options to create contact matrices at specific resolutions and for specific chromosomes.

2.3 Extracting 2D contact matrices from a compressed contact file

A binary contact file in hic format can contain contact matrices at different resolutions. GenomeFlow can read the header of the file first to display information about the genome version, chromosomes, resolutions and normalization methods. Users can then choose the contact matrix of a chromosome at a resolution and normalization method to be exported.

2.4 Normalization, visualization and analysis of 2D contacts

GenomeFlow provides a function to normalize contact matrices in sparse matrix format using the ICE normalization method (Imakaev et al., 2012). GenomeFlow can visualize a contact matrix as a heat map, where numeric values in the input contact matrix are represented as colors according to a selected color gradient (Fig. 1A). GenomeFlow also uses the ClusterTAD (Oluwadare and Cheng, 2017) algorithm to identify topological associated domains (TADs) of contact matrices which can be visualized on the heat map of the contact matrix (Fig. 1A).

2.5 Reconstruction of 3D genome model in real time

GenomeFlow implements two 3D genome reconstruction algorithms [LorDG (Trieu and Cheng, 2016) and 3DMax (Oluwadare et al., 2018)] to reconstruct 3D genome models from contact matrices. Both functions have a user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) and visualize how models are being reconstructed in real time (Fig. 1B). The input of the function is a contact matrix in sparse matrix format. The output 3D models are stored in the GSS format files (Nowotny et al., 2016) that contain both x, y, z coordinates and genomic locations of loci, chromosome number and genome version. Compared to the protein data bank (PDB) format for protein structures, the GSS format can store much larger structures of a chromosome or genome in high resolution and can include extra genomic information needed for function analysis.

2.6 Loop identification in 3D genome models

GenomeFlow provides a function to identify pairs of loci that are very close in 3D space. A pair of loci are considered to be endpoints of chromatin loops if their distance is significantly smaller than loci pairs of the same genomic distance (see details in the supplemental document). This function highlights chromatin loops in 3D genome models (Fig. 1C).

2.7 Annotation of 3D models

GenomeFlow has a function to annotate 3D models by displaying genome annotation tracks in the BED format in the 3D space. Multiple annotations can be displayed in contrasting colors. The function also allows users to visualize genes, enhancers, variants, methylation and other information such as gene expression data on top of 3D genome/chromosome models. This function facilitates the study of the relationship between 3D genome organization and the function (Fig. 1D).

3 Conclusion

We introduced a comprehensive software tool for processing Hi-C data and reconstructing and analyzing 3D genome models. It provides a user-friendly GUI to carry out many steps of analysis and modeling of 3D genome conformation. Users without prior knowledge of the 3D genome can use the tool to build and analyze a 3D genome in their research and work.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Durand N.C. et al. (2016) Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst., 3, 95–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakaev M. et al. (2012) Iterative correction of Hi-C data reveals hallmarks of chromosome organization. Nat. Methods, 9, 999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods, 9, 357.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E. et al. (2009) Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science, 326, 289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny J. et al. (2016) GMOL: an interactive tool for 3D genome structure visualization. Sci. Rep., 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwadare O., Cheng J. (2017) ClusterTAD: an unsupervised machine learning approach to detecting topologically associated domains of chromosomes from Hi-C data. BMC Bioinformatics, 18, 480.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwadare O. et al. (2018) A maximum likelihood algorithm for reconstructing 3D structures of human chromosomes from chromosomal contact data. BMC Genomics, 19, 161.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S.S.P. et al. (2014) A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell, 159, 1665–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M.R., Bengtsson H.L. (2015) Reconstruction of 3D genome architecture via a two-stage algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics, 16, 373.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra F. et al. (2015) Restraint-based three-dimensional modeling of genomes and genomic domains. FEBS Lett., 589, 2987–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu T., Cheng J. (2016) 3D genome structure modeling by Lorentzian objective function. Nucleic Acids Res., 45, 1049–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoquaux N. et al. (2014) A statistical approach for inferring the 3D structure of the genome. Bioinformatics, 30, i26–i33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.