Abstract

Background:

Little is known about differences in the clinical course between patients receiving maintenance dialysis who do and do not withdraw from dialysis.

Study Design:

Case-control analysis.

Setting & Participants:

US patients with Medicare coverage who received maintenance hemodialysis for ≥1 year in 2008 through 2011.

Predictors:

Comorbidity, hospitalizations and skilled nursing facility stays, and a morbidity score based on durable medical equipment claims

Outcome:

Withdrawal from dialysis.

Measurements:

Rates of medical events, hospitalizations and skilled nursing facility stays, and a morbidity score.

Results:

The analysis included 18,367 (7.7%) patients who withdrew and 220,443 (92.3%) who did not. Patients who withdrew were older (mean, 75.3 ± 11.5 [SD] versus 66.2 ± 14.1 years) and more likely to be female and of white race, and had higher comorbidity burdens. The odds of withdrawal among women was 7% (95% CI, 4%−11%) higher than among men. Compared to age 65–74 years, age ≥85 years was associated with a higher adjusted odds of withdrawal (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.54–1.68) and age 18–44 years with a lower adjusted odds (adjusted OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.32–0.40). Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics were less likely to withdraw than whites (adjusted ORs of 0.36 [95% CI, 0.35–0.38], 0.47 [95% CI, 0.42–0.53], and 0.46 [95% CI, 0.44–0.49], respectively). A higher durable medical equipment claims-based morbidity score was associated with withdrawal, even after adjustment for traditional comorbid conditions and hospitalization; compared with a score of 0 (lowest presumed morbidity), adjusted ORs of withdrawal were 3.48 (95% CI, 3.29–3.67) for a score of 3–4 and 12.10 (95% CI, 11.37–12.87) for a score of ≥7. Rates of medical events and institutionalization tended to increase in the months preceding withdrawal, as did morbidity score.

Limitations:

Results may not be generalizable beyond US Medicare patients; people who withdrew <1 year after dialysis initiation were not studied.

Conclusions:

Women, older patients, and those of white race were more likely to withdraw from dialysis. The period before withdrawal was characterized by higher rates of medical events and higher levels of morbidity.

Keywords: dialysis, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), dialysis withdrawal, elective withdrawal, patient-centered care, end-of-life care, comorbidity, durable medical equipement, Medicare

The end-of-life experience for patients receiving maintenance dialysis is a timely area of study. Although annual rates of dialysis initiation have been relatively stable over the past decade,1 dialysis patients now live longer than ever before.2 These developments have recently fostered a keen interest in issues such as conservative care for end-stage renal disease (ESRD),3–6 palliative care in nephrology,7–12 and withdrawal from dialysis.13–19

Elective withdrawal from dialysis is a critically important care option.20–23 Withdrawal from dialysis is a cause of death in approximately 10%−20% of patients in western countries, and it appears to be increasing.24 While several seminal studies have examined the factors associated with dialysis withdrawal,14,15,25,26 nearly all appear to have used data assessed primarily at the time of dialysis initiation. However, except in the case of incident patients who experience early withdrawal,18 this approach may not fully capture the clinical scenarios that characterize the dialysis withdrawal experience. In “real-life” clinical environments, the decision to withdraw from dialysis probably reflects bedside realities such as increasing comorbidity burden, increasing disability, and increasing use of the health care proximal to the withdrawal decision.

We therefore designed a study to examine clinical events in the period preceding withdrawal in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Using a large sample from a national registry of patients receiving dialysis, we sought to characterize the patients who withdrew from dialysis and to contrast them with patients who did not withdraw. Specifically, we examined rates of medical events, time spent in the hospital and in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and putative markers morbidity drawn in part from claims for durable medical equipment (DME) use in the period preceding withdrawal to determine how patients who withdraw might differ from those who do not. We hypothesized that the period before withdrawal would be characterized by increasing rates of medical events, institutionalization, and other markers that potentially signal morbidity.

Methods

Data Sources

The US Renal Data System (USRDS) ESRD database was used for this study. The USRDS ESRD database consists of data from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report, the ESRD Death Notification form, and Medicare Parts A and B claims. From Medicare, which insures the majority of patients who receive maintenance dialysis, we used billing claims data to determine the presence of comorbid conditions, to derive the Liu comorbidity index,27 and to generate a putative marker of morbidity based in part on claims for DME use (further described in the next section).

Study Design

The present study used a case-control design. The case patients were individuals who withdrew from hemodialysis between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2011. For each patient who withdrew, we created an index date, defined as the date of withdrawal. We then identified hemodialysis patients who did not withdraw and created their respective index dates, defined as the calendar date on which dialysis duration was within ± 30 days of dialysis duration among patients who withdrew. By matching based on a similar dialysis duration (that is, time between dialysis initiation and index date), we identified appropriate non-withdrawal controls for the patients who withdrew.

All patients were required to have received hemodialysis for at least 1 year as of the index date (because our intention was to study prevalent hemodialysis patients who had ample exposure to the dialysis experience), to have been insured by Medicare Parts A and B for at least 9 months, and to have been aged 18 years or older. To assess factors associated with withdrawal, we compared the patient demographic factors, comorbid conditions, and other indicators of health (described more fully in later paragraphs) between the withdrawers and the non-withdrawers. This group was matched only on dialysis duration (the minimum criteria required to create an informative comparison between withdrawers and non-withdrawers), and is henceforth referred to as the match 1 group.

Because we hypothesized that patient factors such as age, sex, and race might be highly associated with comorbid conditions, hospitalization days, and other markers of potential morbidity such as use of DME, we undertook a second, more comprehensively matched analysis. For this analysis, we explicitly matched each withdrawal patient with four non-withdrawal patients, selected at random, on the basis of age (< 1 year difference), race, sex, cause of ESRD, and dialysis duration (< 1 year difference), thereby creating what we term the match 2 group. Controls could be matched to one case patient only.

To create both contrasts, we looked back 9 months preceding the index date to determine patterns of medical events, hospitalizations and SNF stays, and the morbidity score to create a comprehensive picture of medical status in the months preceding the index date. Visual inspection of the data suggested that 9 months represented an acceptable tradeoff between a too-short observation period (e.g., 3 months) and an overly long one (e.g., 12 months). That is, the patterns observed in the data between 12 and 9 months before the index date appeared similar to the patterns observed between 9 and 6 months before the index date.

Determination of Withdrawal

Details of our definition of dialysis withdrawal appear in Item S1. In brief, presence of code 104 in the first or second position of question 12 on the USRDS Death Notification form plus an answer “yes” to question 14 (“Was discontinuation of renal replacement therapy after patient/family request to stop dialysis?”) was required. We also required death ≥ 1 day after withdrawal to eliminate patients who likely faced imminent death and did not truly withdraw (as withdrawal is commonly understood). To take into account possible misclassification of patients who did not withdraw as withdrawers, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which we required 5 days of survival after withdrawal.

Medical Events, Institutionalizations, and Other Putative Markers of Morbidity

Medical events assessed were hospitalizations for myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, amputation/critical limb ischemia, sepsis, pneumonia, vascular access infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, or fracture; relevant codes used to identify these events are listed in Table S1. Of these, the subset of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction, stroke, amputation/critical limb ischemia, sepsis, or fractures constituted “major medical events.” Medical events were identified from inpatient claims for each month over the 9-month period preceding the index date. Event rates were calculated on a monthly basis; numbers of institutionalized days were calculated on a monthly basis. Events were considered on an individual basis; for example, for a hospitalization for a fracture resulting in a subsequent myocardial infarction, each event was counted individually.

To create a morbidity score that might reflect difficult-to-define phenomena such as disability, we employed a variation of a previously developed claims-based algorithm.28 A complete description of the method appears in Item S2. Briefly, potential markers of morbidity from the DME files were chosen by first limiting to those with prevalence greater than 1%, and further limiting to those with an association with mortality, hospitalization, or fracture. Proportional hazards models were used to investigate the association of these markers with mortality, hospitalization, and fracture. The morbidity score for each patient was created by taking parameter estimates from the adjusted proportional hazards model, multiplying the parameter estimates by 10, rounding to integer, and summing the markers present in each patient. Relevant diagnosis codes appear in Table S2. Given the nature of DME, the mean monthly morbidity score was calculated iteratively using data over the previous 3 months. For purposes of modeling (described in the Statistical Analysis section), only the morbidity score ascertained as of the index date was used.

Demographic and Comorbidity Variables

Other included variables were age, race, sex, cause of ESRD, and dialysis duration (all derived from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report). Comorbid conditions included diabetes, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, other cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular events (including transient ischemic attack), dysrhythmias, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal and liver disorders, and cancer. Comorbid conditions were ascertained from medical claims over the 9-month period preceding the index date by the presence of one or more inpatient or two or more outpatient/Part B claims combined with comorbid conditions listed on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS)-2728 Medical Evidence Report, consistent with prior approaches.27–29 The conditions assessed and the associated identification approach are shown in Item S3 and Table S3.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics (count [n], percentage [%]) to characterize the analyzed patients. For each month, medical event rates were calculated as number of events in the month per 1000 days (assuming 30 days in a month); lengths of stay for hospitalizations and SNFs were calculated as number of hospital/SNF days per 100 patient-days. All rates were plotted over time to show the evolving pattern in the period preceding the index date.

For the more fully matched analysis (match 2), cases were matched 4 to 1 with controls on the five variables (age, sex, race, cause of ESRD, and dialysis duration); for the match 1 analysis, we matched only on the basis of dialysis duration. Match 1 used all eligible controls (i.e., those who satisfied the same age, dialysis duration, and insurance coverage criteria as the withdrawers). Conditional logistic regression, conditioned on the match, was used for the match 2 analysis. However, because all eligible controls were used in match 1, conditional logistic regression proved to be computationally challenging for the match 1 analysis given the large sample size. We therefore compared the results of the conditional and unconditional analyses for match 2 and, finding them very similar, elected to perform unconditional logistic regression for match 1. For the match 1 analysis, the model was adjusted for age, sex, race, dialysis duration, cause of ESRD, comorbid conditions, institutionalized days, and our morbidity proxy score; for the match 2 analysis, the model was adjusted only for comorbid conditions, institutionalized days, and the morbidity score. Age, dialysis duration, comorbid conditions, and morbidity score were calculated at the index date.

Finally, we assessed location of withdrawal (hospital versus other) among the patients who withdrew; a logistic model was used to identify factors related to withdrawal in the hospital. We used the Liu comorbidity index to represent overall disease burden, since the effect of disease burden on the location of withdrawal seemed likely to be more clinically relevant than individual comorbid conditions. The resultant comorbidity index is a weighted sum of comorbid conditions based on presence of each condition; the weight of each condition was determined based on its relationship to death, as described in detail previously.27

Compliance and Protection of Human Research Participants

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Hennepin County Medical Center, which provided a waiver of informed consent since all data were de-identified. Data Use Agreements (DUAs) between the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation and the USRDS and CMS were in place.

Results

Characteristics of Analyzed Sample

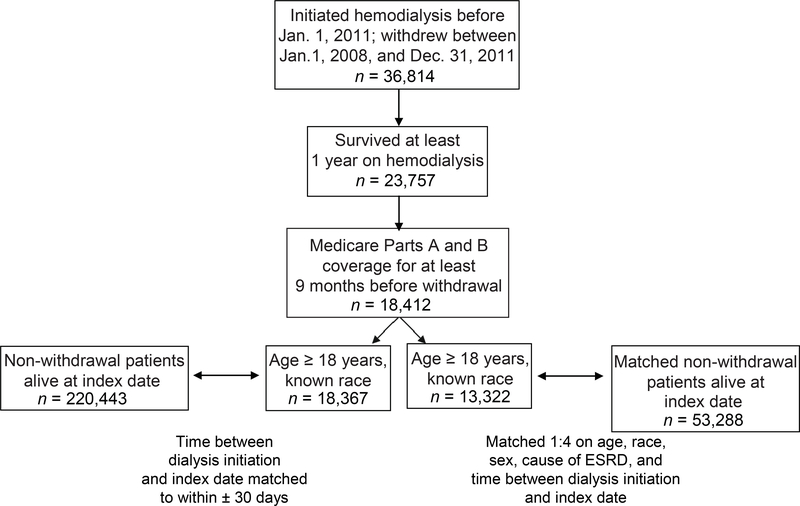

Of 36,814 individuals who initiated maintenance hemodialysis on or before January 1, 2011, and who withdrew January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2011, there were 18,412 who survived at least 1 year on hemodialysis and had at least 9 months of Medicare Parts A and B coverage immediately preceding their respective index dates (Figure 1). Of these, 18,367 were adults of known race for whom comparable non-withdrawal patients could be found on the basis of the index date; the former thus constituted the case patients s for the match 1 analysis, and the latter (n = 220,443), the controls.

Figure 1.

Creation of the analytic sample

Among patients who withdrew, 13,322 were then more fully matched 1:4, at random, with non-withdrawers with similar age, sex, race, cause of ESRD, and dialysis duration as of the index date (match 2). This resulted in 53,288 more fully matched patients who did not withdraw.

Characteristics of withdrawers and those who did not withdraw in the two groups are shown in Table 1. In the match 1 group, patients who withdrew were substantially older (mean age, 75.3 ± 11.5 [standard deviation] versus 66.2 ± 14.1 years), and more likely to be female, to be white rather than of a minority race/ethnicity (71.8% versus 46.2%), and to have longer dialysis duration (4.8 ± 3.8 versus 4.5 ± 3.9 years). Patients who withdrew generally had higher comorbidity burdens and morbidity scores (e.g., 22.4% versus 3.5% in the highest score category, indicating greatest apparent morbidity). In the match 2 group, distributions of the matched variables differed only slightly, as designed, suggesting that the more complete matching strategy generated generally comparable groups across the factors used for the match. However, withdrawers had generally higher comorbidity burdens and higher scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients

| Characteristics | Withdrew, Match 1† (n=18,367) | Did not Withdraw, Match 1† (n=220,443) | Withdrew, Match 2‡ (n=13,322) | Did not Withdraw, Match 2‡ (n=53,288) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 75.3 ±11.5 | 66.2 ±14.1 | 73.3 ±10.8 | 73.3 ±10.8 |

| Age category | ||||

| 18–44 y | 1.6( 294) | 8.0 (17,679) | 1.4 (186) | 1.3 (705) |

| 45–64 y | 16.2 (2983) | 35.7 (78,649) | 19.7 (2625) | 19.9 (10,593) |

| 65–74 y | 25.1 (4606) | 26.7 (58.838) | 29.8 (3971) | 29.8 (15,857) |

| 75–84 y | 36.2 (6645) | 22.0 (48,574) | 35.9 (4785) | 36.0 (19,185) |

| ≥ 85 y | 20.9 (3839) | 7.6( 16,703) | 13.2 (1755) | 13.0 (6948) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 49.2 (9045) | 44.3 (97,710) | 47.1 (6279) | 47.1 (25,116) |

| Male | 50.8 (9322) | 55.7 (122,733) | 52.9(7043) | 52.9 (28,172) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 71.8 (13,194) | 46.2 (101,855) | 68.5 (9122) | 68.5 (36,488) |

| Black | 17.0 (3125) | 35.3 (77,821) | 20.9 (2789) | 20.9 (11,156) |

| Asian | 2.0 (362) | 3.4 (7487) | 1.3 (169) | 1.3 (676) |

| Native American | 1.1 (202) | 1.2 (2714) | 0.5 (72) | 0.5 (288) |

| Hispanic | 8.1 (1484) | 13.9 (30,566) | 8.8 (1170) | 8.8 (4680) |

| Dialysis duration, y | 4.8 ±3.8 | 4.5 ±3.9 | 4.0 ±2.7 | 4.0 ±2.7 |

| Dialysis duration group | ||||

| 1-< 2 y | 21.0 (3855) | 28.1 (62,014) | 26.4 (3523) | 26.4 (14,044) |

| 2-< 3 y | 17.1 (3132) | 16.6 (36,648) | 19.3 (2566) | 20.1 (10,734) |

| 3-< 4 y | 14.4 (2651) | 13.7 (30,256) | 14.7 (1961) | 14.5 (7724) |

| 4-< 5 y | 12.0 (2212) | 10.3 (22,683) | 11.6 (1545) | 11.8 (6276) |

| ≥ 5 y | 35.5 (6517) | 31.2 (68,842) | 28.0 (3727) | 27.2 (14,510) |

| Primary cause of ESRD | ||||

| Diabetes | 46.0 (8452) | 49.2 (108,537) | 51.7 (6882) | 51.7 (27,528) |

| Hypertension | 30.5 (5607) | 28.6 (63,060) | 29.6 (3946) | 29.6 (15,784) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 8.0 (1463) | 9.0 (19,940) | 5.4 (725) | 5.4 (2900) |

| Other | 15.5 (2845) | 13.1 (28,906) | 13.3 (1769) | 13.3 (7076) |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 66.8 (12,271) | 50.4 (111,182) | 67.9 (9051) | 57.2 (30,502) |

| Congestive heart failure | 73.6 (13,515) | 58.8 (129,717) | 74.8 (9965) | 61.3 (32,666) |

| Dysrhythmia | 53.4 (9815) | 30.0 (66,066) | 52.5 (6988) | 34.8 (18,560) |

| CVA/TIA | 36.5 (6701) | 20.6 (45,419) | 38.7 (5150) | 22.0 (11,741) |

| Other cardiac disease | 45.2 (8303) | 30.3 (66,834) | 46.4 (6178) | 31.3 (16,668) |

| PVD | 57.6 (10,584) | 40.3 (88,787) | 59.4 (7919) | 42.9 (22,861) |

| Hypertension | 84.5 (15,523) | 84.4 (186,071) | 86.3 (11,499) | 85.3 (45,470) |

| Diabetes | 69.2 (12,710) | 69.6 (153,453) | 74.2 (9881) | 71.3 (38,004) |

| COPD | 39.0 (7157) | 27.1 (59,729) | 40.0 (5331) | 30.1 (16,036) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 15.1 (2766) | 7.3 (16,165) | 15.3 (2038) | 6.6 (3542) |

| Liver disease | 9.5 (1747) | 7.9 (17,367) | 10.0 (1338) | 7.2 (3860) |

| Cancer | 21.1 (3896) | 10.8 (23,698) | 21.2 (2823) | 13.1 (6967) |

| Morbidity score§ | ||||

| 0 | 14.5 (2661) | 51.6 (113,731) | 13.5 (1794) | 49.9 (26,606) |

| 1–2 | 21.5 (3943) | 21.3 (46,872) | 21.5 (2859) | 21.0 (11,190) |

| 3–4 | 25.7 (4723) | 17.4 (38,295) | 25.5 (3394) | 19.0 (10,148) |

| 5–6 | 15.9 (2920) | 6.2 (13,777) | 16.3 (2165) | 6.5 (3454) |

| ≥ 7 | 22.4 (4120) | 3.5 (7768) | 23.3 (3110) | 3.5 (1890) |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation.

The basis of comparison for the match 1 group was establishment of an “index date,” the date of withdrawal for those who withdrew and a counterfactual date for those who did not withdraw; see text for details.

Matching for the match 2 group occurred on the basis of age, sex, race, dialysis duration, and cause of ESRD; see text for details.

Higher scores indicate greater apparent degree of morbidity; see text for explanation of the morbidity score.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Factors Associated With Withdrawal

The comparison of factors associated with withdrawal from the conditional logistic model is shown in Table 2 for both match 1 and match 2 groups. In the former, older age was associated with withdrawal; compared with patients aged 65–74 years, adjusted ORs for withdrawal were 1.61 (95% CI, 1.54–1.68) for patients aged 75–84 years and 2.68 (95% CI, 2.54–2.82) for patients aged ≥ 85 years; the adjusted OR was 0.36 (95% CI, 0.32–0.40) for patients aged 18–44 years. Women were more likely than men to withdraw (adjusted OR, 1.07; 95% CI. 1.04–1.11). Except for Native Americans (the numerically smallest group represented), non-white patients, compared with white patients, had lower odds of withdrawal: adjusted ORs were 0.36 (95% CI, 0.35–0.38) for blacks, 0.47 (95% CI, 0.42–0.53) for Asians, and 0.46 (95% CI, 0.44–0.49) for Hispanics. Longer dialysis duration was associated with withdrawal; for example, compared with duration of 3-< 4 years, adjusted ORs for withdrawal were 0.55 (95% CI, 0.52–0.58) for 1-< 2 years duration but 1.37 (95% CI, 1.30–1.44) for ≥ 5 years. Institutionalization (hospital stay or SNF) was associated with increased odds of withdrawal (1.01 per each day of institutionalization). A higher morbidity score was associated with increased likelihood of withdrawal; compared with a score of 0, a score of 3–4 was associated with an adjusted OR of 3.48 (95% CI, 3.29–3.67) and a score of ≥ 7, with an adjusted OR of 12.10 (95% CI, 11.37–12.87).

Table 2.

Factors associated with withdrawal

| Match 1** | Match 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Age category | ||||

| 18–44 y | 0.36 (0.32–0.40) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| 45–64 y | 0.61 (0.58–0.64) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| 65–74 y | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 75–84 y | 1.61 (1.54–1.68) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| ≥ 85 y | 2.68 (2.54–2.82) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Female sex | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Black | 0.36 (0.35–0.38) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Asian | 0.47 (0.42–0.53) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Native American | 0.92 (0.78–1.07) | 0.3 | -- | -- |

| Hispanic | 0.46 (0.44–0.49) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Dialysis duration group | ||||

| 1-< 2 y | 0.55 (0.52–0.58) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| 2-< 3 y | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| 3-< 4 y | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 4-<5 y | 1.16 (1.09–1.24) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| ≥ 5 y | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Cause of ESRD | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Hypertension | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | < 0.001 | -- | -- |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) | 0.6 | -- | -- |

| Other | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.02 | -- | -- |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 0.91 (0.88–0.95) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | < 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.7 | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) | 0.5 |

| Dysrhythmia | 1.25 (1.20–1.29) | < 0.001 | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) | < 0.001 |

| CVA/TIA | 1.25 (1.21–1.30) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.24–1.36) | < 0.001 |

| Other cardiac disease | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.11–1.22) | < 0.001 |

| PVD | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.04 | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | 0.06 |

| COPD | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1.29 (1.23–1.36) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.33–1.53) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.55 (1.49–1.62) | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.55–1.74) | < 0.001 |

| Institutionalized days, per 1-d greater | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.001 |

| Morbidity score* | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 1–2 | 2.80 (2.65–2.95) | < 0.001 | 2.98 (2.79–3.19) | < 0.001 |

| 3–4 | 3.48 (3.29–3.67) | < 0.001 | 3.71 (3.46–3.98) | < 0.001 |

| 5–6 | 5.10 (4.78–5.43) | < 0.001 | 5.75 (5.28–6.26) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 7 | 12.10 (11.37–12.87) | < 0.001 | 14.68 (13.47–16.01) | < 0.001 |

Note: In the match 1 analysis, patients who withdrew were matched with those who did not withdraw only on the basis of dialysis duration; the match 2 analysis required matching of patients who did and did not withdraw on the basis of age, sex, race, cause of ESRD, and dialysis duration. See text for details. Unconditional logistic regression was used for the match 1 analysis; conditional logistic regression was used for the match 2 analysis.

Higher scores indicate greater apparent degree of morbidity; see text for explanation of the morbidity score. CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA/TIA, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OR, odds ratio; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

P for intercept < 0.001

For the match 2 group, findings were similar for institutionalization, comorbid conditions, and morbidity score. As with the match 1 group, institutionalization was associated with increased odds of withdrawal (1.01 per each additional day). Morbidity score remained strongly associated with withdrawal; adjusted ORs were 3.71 (95% CI, 3.46–3.98) for a score of 3–4, 5.75 (95% CI, 5.28–6.26) for a score of 5–6, and 14.68 (95% CI, 13.47–16.01) for a score of ≥ 7.

In the sensitivity analysis imposing a 5-day survival period after withdrawal designed to minimize potential misclassification of withdrawal patients, findings were similar (Table S4).

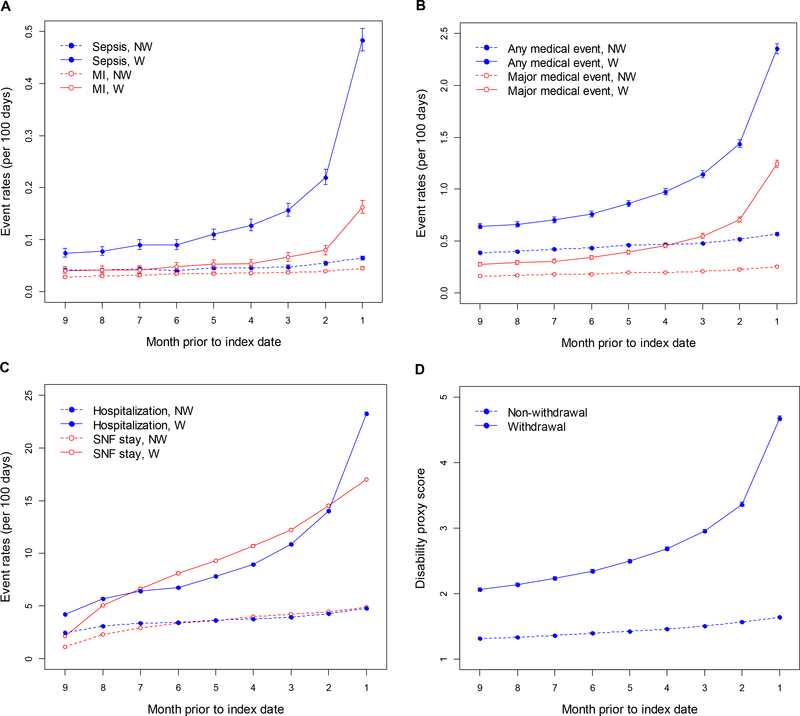

Rates of Events and Health Care Encounters Before Withdrawal

Examination of the match 2 group demonstrated that rates of medical events generally increased approximately 2- to 5-fold over the 9 months before the index date (i.e., before withdrawal) in patients who withdrew, especially in the 2 months before, but appeared to increase only slightly over time in patients who did not withdraw (Figure 2). Rates of institutionalization appeared to follow a similar pattern. Morbidity score also worsened, particularly in the final 2 months before withdrawal, in patients who withdrew, but appeared to increase only slightly over time in patients who did not withdraw. The same general pattern of medical events and morbidity score (Figure S1) in the period preceding the index date was apparent when only the withdrawers who survived at least 5 days after withdrawal were included.

Figure 2.

Rate estimates (per 100 days) for clinical events (admissions for sepsis and MI, panel A; admission for any medical event and major medical events, panel B), institutionalization (hospitalization and admission to SNFs, panel C), and changes in morbidity score (panel D) over the 9 months preceding the index date in the groups, by withdrawal status. The index data is the date of withdrawal for those who withdrew, and a counterfactual date for those who did not withdraw; see text for details. Confidence intervals are present for each data point; however, they are narrow and thus difficult to discern. MI, myocardial infraction; NW, non-withdrawer; SNF, skilled nursing facility; W, withdrawer.

Location of Withdrawal and Associated Factors

For withdrawers, mean time between last dialysis treatment and death was 11.1 (median, 8; 25th and 75th percentiles, 5 and 13) days; 36.2% made the decision while in the hospital and 16.8% while in an SNF. Thus, 53.0% withdrew while in an institutionalized setting. Factors associated with in-hospital withdrawal, among those who withdrew, are shown in Table 3. Generally, older age was associated with decreased likelihood of withdrawing in the hospital. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were 0.75 (95% CI, 0.68–0.82) for ages ≥ 85 years (reference group, ages 65-< 74 years) and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81–0.95) for ages 75–84 years. Likelihood of withdrawal in the hospital tended to be highest for the youngest patients (AOR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.32–2.16). Women were more likely to withdraw in the hospital (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.06–1.20), as were Hispanic (AOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.02–1.29) and, particularly, black patients (AOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.26–1.49), compared with white patients. Greater comorbidity was associated with increased likelihood of in-hospital withdrawal. However, higher morbidity score was inversely associated with in-hospital withdrawal; patients with the highest score (≥ 7) were significantly less likely to withdraw in the hospital (AOR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.40–0.50).

Table 3.

Odds ratios for dialysis withdrawal, among those who withdrew in hospital (vs. not in hospital)

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age category | ||

| 18–44 y | 1.69 (1.32–2.16) | < 0.001 |

| 45–64 y | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | < 0.001 |

| 65–74 y | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 75–84 y | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | 0.002 |

| ≥ 85 y | 0.75 (0.68–0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.12 (1.06–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Black | 1.37 (1.26–1.49) | < 0.001 |

| Asian | 0.96 (0.77–1.21) | 0.8 |

| Native American | 0.87 (0.64–1.17) | 0.4 |

| Hispanic | 1.14 (1.02–1.29) | 0.02 |

| Dialysis duration group | ||

| 1–< 2 y | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 0.7 |

| 2–< 3 y | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.5 |

| 3–<4 y | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 4–<5 y | 1.01 (0.98–1.14) | 0.9 |

| ≥ 5 y | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) | 0.1 |

| Primary cause of ESRD | ||

| Diabetes | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Hypertension | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 0.8 |

| GN | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 0.2 |

| Other cause | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | 0.001 |

| Liu comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 1–4 | 2.03 (1.34–3.07) | < 0.001 |

| 5–7 | 3.27 (2.18–4.92) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 8 | 5.47 (3.65–8.20) | < 0.001 |

| Morbidity score* | ||

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 1–2 | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) | < 0.001 |

| 3–4 | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 0.01 |

| 5–6 | 1.15 (1.03–1.29) | 0.02 |

| ≥ 7 | 0.44 (0.40–0.50) | < 0.001 |

P for intercept < 0.001

Higher scores indicate greater apparent degree of morbidity; see text for explanation of the morbidity score.

CI, confidence interval; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GN, glomerulonephritis; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Withdrawal from dialysis appears to be an increasingly common cause of death in dialysis patients,14,15,24 but this phenomenon remains underexplored. In this large, contemporary sample of patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis, we found, not unexpectedly, that in the months prior to withdrawal, rates of medical events and institutionalized time increased. However, our claims-based proxy for morbidity, which relied heavily on DME use and might therefore be a marker of disability, further distinguished those who withdrew from those who did not, as this score increased in the months before withdrawal. Additionally, black, Hispanic, and Asian patients were more likely to withdraw from dialysis than whites, and men were less likely to withdraw than women, even after adjustment for a broad range of characteristics, suggesting that cultural or social factors, as yet not fully defined, may be associated with withdrawal. Older age was associated with withdrawal outside (versus inside) the hospital, while black and Hispanic race/ethnicity was associated with in-hospital withdrawal. A higher morbidity score was associated with out-of-hospital withdrawal. Given the growth, aging, and demographic changes of the US dialysis population and society’s increased focus on the end-of-life experience for chronically ill patients,30–33 our study presents important new findings regarding the withdrawal experience for patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis.

Our study design differed fundamentally from designs of previous investigations, which generally modelled likelihood of future withdrawal based on an assessment of characteristics at the time of dialysis initiation. We reasoned that the withdrawal experience was likely heavily influenced by the series of events preceding withdrawal, so we elected to anchor our analysis at time of withdrawal and then look back, since both acute and chronic health status likely affects the decision to withdraw.14,15,19,25,26,34 Regarding acute health status (defined here as the approximately 2–3 months before withdrawal), event rates generally increased progressively up to the time of withdrawal (a pattern consistent with results from Bajwa et al34) but not before the analogous index date in those who did not withdraw. This was true for nearly all types of clinical events examined, our two summary measures of medical events, our two utilization-of-care measures, and our DME claims-based morbidity score.

To investigate the potential importance of DME use as a marker of morbidity, we conducted analyses employing varying degrees of matching. The analysis that matched only on the basis of dialysis duration (defined in this study as the time between dialysis initiation and index date; the minimum step required to construct a fair contrast) permits inferences to be made about the association of factors such as age, sex, race, and cause of ESRD with withdrawal. The more fully matched exercise, in turn, was undertaken to reduce residual confounding and resultant bias potentially associated with the aforementioned demographic factors, likely permitting more precise quantification of the strength of association between our DME claims-based morbidity score and withdrawal. In both analyses, this score appears to have a strikingly strong association with withdrawal independent of traditional factors such as a demographics and comorbidity. This suggests that nephrologists and other providers should be particularly mindful of the role that putative markers of morbidity beyond traditional medical comorbidity, such as conditions for which DME use may be an indication, appears to have in the decision to withdraw.

In the absence of validation, the precise phenomenon measured by our morbidity score is uncertain. Without direct measures of disability or functional status, it is premature to suggest that our score measures either of these. While it is not unintuitive that degree of morbidity signified, in part, by DME use might factor into the decision to withdraw from dialysis, our study demonstrates this potential link through use of a large, observational database. Development of validated claims-based measures of disability and, preferably, functional status suitable for use in large observational databases has been advocated and attempted by others in the nondialysis population35;36; development of such as measure in the dialysis population would improve the utility of observational databases to study key epidemiological questions. Perhaps more importantly, the present findings might inform future efforts to study the withdrawal experience, which could be undertaken using a qualitative research framework. This approach would be well suited to investigating patient-oriented outcomes and patient preferences, since it involves explicit consideration of perspectives directly expressed by patients themselves. Assessment of factors such as patients’ ability to perform activities of daily living, objective measures of disability, and patients’ self-perception of overall health status, while not typically obtainable in large observational databases, are likely required before a full understanding of the withdrawal experience can be attained.

Our work also demonstrates important demographic factors associated with withdrawal. Men were less likely to withdraw than women, possibly suggesting that men are less likely than women to move (or to be moved) toward withdrawal. This appears to be concordant with recent evidence from the general population that men are more likely than women to receive intensive chemotherapy at the end of life,37 and duration of hospice services is shorter for men across a broad range of terminal conditions.38 These findings suggest that poorly understood factors, perhaps encompassing societal sex roles, may be operative in dialysis patients.

Concerning race, some non-white groups were less likely than whites to withdraw from dialysis, and, when they did withdraw, to do so outside the hospital. Possibly, black and Hispanic patients, or those who influence their health care decisions, could have a higher “threshold” for electing to withdraw than whites. If so, this would be concordant with other studies using alternative designs.14,15,25,26 Cultural or societal factors may play a role in this phenomenon. Also, as-yet-undefined barriers to withdrawal may exist, including the possibility that nephrologists and other providers do not discuss dialysis withdrawal in the same terms, or with the same frequency or intensity, with black or other minority patients relative to white patients. Racial differences in end-of-life care in dialysis require further study.

Roughly one in three patients withdrew from dialysis in the hospital and one in six in an SNF, meaning that over half of patients withdrew in a non-institutional setting. The importance of SNF placement as a factor associated with withdrawal has been highlighted elsewhere.26 Older patients were relatively more likely to withdraw in a noninstitutional setting, a finding that may reflect a complex interaction of health care system factors, societal views on withdrawal, or other factors. Further examination of the reasons for this should be undertaken.

Our study has several important limitations. First, we studied only US patients insured by Medicare, meaning that generalizability to other populations is limited, especially to patients in other countries where the sociocultural milieu involving withdrawal from dialysis, and of end-of-life care in general, may differ. We cannot comment on the withdrawal of patients who are new to dialysis (i.e., < 1 year). Additionally, it is uncertain whether our morbidity score, while to our knowledge novel, truly identifies some degree of disability or functional status or is merely a proxy for other factors; this score awaits validation using other, more granular, sources of data.

In conclusion, the period before dialysis withdrawal was characterized by increasing rates of medical events and hospitalization. A marker of morbidity based on DME use appears to be strongly associated with withdrawal, even after adjustment for a host of other factors. Men and members of certain minority groups, such as blacks, Asians, and Hispanics, were less likely to withdraw than women and whites. When they did withdraw, blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites to withdraw in the hospital. Further work examining elective dialysis withdrawal experience is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Rate estimates for clinical events and changes in morbidity score over the 9 mo preceding index date in withdrawers who survived at least 5 d after withdrawal and controls.

Item S1: Determination of dialysis withdrawal.

Item S2: Morbidity score.

Item S3: Identification of comorbid conditions.

Table S1: Event codes.

Table S2: HCPCS and ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes used to define morbidity score.

Table S3: ICD-9-CM diagnosis and V codes used to define comorbid conditions.

Table S4: Factors associated with withdrawal among patients who survived at least 5 d after withdrawal.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Chronic Disease Research Group colleagues Anne Shaw for manuscript preparation and Nan Booth, MSW, MPH, ELS, for manuscript editing.

Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) grant #DK104006 to Dr Wetmore. The funding agency had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Disclaimer: The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS (DUA#2007–10 & 2009–19) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (DUA#19707). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).United States Renal Data System. 2015 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. 2015. ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Weinhandl E, Constantini E, Everson S, et al. Peer Kidney Care Initiative 2014 report: dialysis care and outcomes in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(6 Suppl 1):Svi, S1–S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Murtagh FE, Cohen LM, Germain MJ. The “no dialysis” option. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(6):443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Murtagh FE, Burns A, Moranne O, Morton RL, Naicker S. Supportive care: Comprehensive conservative care in end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1909–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Davison SN, Jassal SV. Supportive care: Integration of patient-centered kidney care to manage symptoms and geriatric syndromes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1882–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Morton RL, Kurella TM, Coast J, Davison SN. Supportive care: Economic considerations in advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1915–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).O’Connor NR, Kumar P. Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Muthalagappan S, Johansson L, Kong WM, Brown EA. Dialysis or conservative care for frail older patients: ethics of shared decision-making. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2717–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Van Biesen W, van de Luijtgaarden MW, Brown EA, et al. Nephrologists’ perceptions regarding dialysis withdrawal and palliative care in Europe: lessons from a European Renal Best Practice survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(12):1951–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fung E, Slesnick N, Kurella TM, Schiller B. A survey of views and practice patterns of dialysis medical directors toward end-of-life decision making for patients with end-stage renal disease. Palliat Med. 2016;30(7):653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lazenby S, Edwards A, Samuriwo R, Riley S, Murray MA, Carson-Stevens A. End-of-life care decisions for haemodialysis patients - ‘We only tend to have that discussion with them when they start deteriorating.’ Health Expect. 2017;20(2):260–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Couchoud C, Bello AD, Lobbedez T, et al. Access to and characteristics of palliative care-related hospitalization in the management of end-stage renal disease patients on renal replacement therapy in France. Nephrology (Carlton ). 2017;22(8):598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kurella TM, Goldstein MK, Perez-Stable EJ. Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chan HW, Clayton PA, McDonald SP, Agar JW, Jose MD. Risk factors for dialysis withdrawal: an analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry, 1999–2008. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(5):775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ellwood AD, Jassal SV, Suri RS, Clark WF, Na Y, Moist LM. Early dialysis initiation and rates and timing of withdrawal from dialysis in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(2):265–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).O’Hare AM, Vig EK, Hebert PL. Initiation of dialysis at higher levels of estimated GFR and subsequent withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(2):179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Aggarwal Y, Baharani J. End-of-life decision making: withdrawing from dialysis: a 12-year retrospective single centre experience from the UK. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(4):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Couchoud CG, Beuscart JB, Aldigier JC, Brunet PJ, Moranne OP. Development of a risk stratification algorithm to improve patient-centered care and decision making for incident elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88(5):1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Findlay MD, Donaldson K, Doyle A, et al. Factors influencing withdrawal from dialysis: a national registry study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(12):2041–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Renal Physicians Association. Shared Decision Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, 2nd Edition. Available at: https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.renalmd.org/resource/resmgr/Store/Shared_Decision_Making_Recom.pdf?hhSearchTerms=%22shared+and+decision+and+making%22. 2016. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- (21).Schmidt RJ, Moss AH. Dying on dialysis: the case for a dignified withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hussain JA, Flemming K, Murtagh FE, Johnson MJ. Patient and health care professional decision-making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Watanabe Y, Hirakata H, Okada K, et al. Proposal for the shared decision-making process regarding initiation and continuation of maintenance hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19 (Suppl 1):108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Murphy E, Germain MJ, Cairns H, Higginson IJ, Murtagh FE. International variation in classification of dialysis withdrawal: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(3):625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Leggat JE Jr., Bloembergen WE, Levine G, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Port FK. An analysis of risk factors for withdrawal from dialysis before death. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(11):1755–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fissell RB, Bragg-Gresham JL, Lopes AA, et al. Factors associated with “do not resuscitate” orders and rates of withdrawal from hemodialysis in the international DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Liu J, Huang Z, Gilbertson DT, Foley RN, Collins AJ. An improved comorbidity index for outcome analyses among dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;77(2):141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wetmore JB, Liu J, Wirtz HS, et al. Geovariation in Fracture Risk among Patients Receiving Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(8):1413–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Slinin Y, Guo H, Li S, et al. Hemodialysis patient outcomes: provider characteristics. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(5):367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Blinderman CD, Billings JA. Comfort Care for Patients Dying in the Hospital. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(26):2549–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and Practices of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bajwa K, Szabo E, Kjellstrand CM. A prospective study of risk factors and decision making in discontinuation of dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2571–2577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Davidoff AJ, Zuckerman IH, Pandya N, et al. A novel approach to improve health status measurement in observational claims-based studies of cancer treatment and outcomes. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(2):157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(1):59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rochigneux P, Raoul JL, Beaussant Y, et al. Use of chemotherapy near the end of life: what factors matter? Ann Oncol. 2017;28(4):809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bennett MI, Ziegler L, Allsop M, Daniel S, Hurlow A. What determines duration of palliative care before death for patients with advanced disease? A retrospective cohort study of community and hospital palliative care provision in a large UK city. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Rate estimates for clinical events and changes in morbidity score over the 9 mo preceding index date in withdrawers who survived at least 5 d after withdrawal and controls.

Item S1: Determination of dialysis withdrawal.

Item S2: Morbidity score.

Item S3: Identification of comorbid conditions.

Table S1: Event codes.

Table S2: HCPCS and ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes used to define morbidity score.

Table S3: ICD-9-CM diagnosis and V codes used to define comorbid conditions.

Table S4: Factors associated with withdrawal among patients who survived at least 5 d after withdrawal.