Abstract

Background

Decision aids are interventions that support patients by making their decisions explicit, providing information about options and associated benefits/harms, and helping clarify congruence between decisions and personal values.

Objectives

To assess the effects of decision aids in people facing treatment or screening decisions.

Search methods

Updated search (2012 to April 2015) in CENTRAL; MEDLINE; Embase; PsycINFO; and grey literature; includes CINAHL to September 2008.

Selection criteria

We included published randomized controlled trials comparing decision aids to usual care and/or alternative interventions. For this update, we excluded studies comparing detailed versus simple decision aids.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently screened citations for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. Primary outcomes, based on the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS), were attributes related to the choice made and the decision‐making process.

Secondary outcomes were behavioural, health, and health system effects.

We pooled results using mean differences (MDs) and risk ratios (RRs), applying a random‐effects model. We conducted a subgroup analysis of studies that used the patient decision aid to prepare for the consultation and of those that used it in the consultation. We used GRADE to assess the strength of the evidence.

Main results

We included 105 studies involving 31,043 participants. This update added 18 studies and removed 28 previously included studies comparing detailed versus simple decision aids. During the 'Risk of bias' assessment, we rated two items (selective reporting and blinding of participants/personnel) as mostly unclear due to inadequate reporting. Twelve of 105 studies were at high risk of bias.

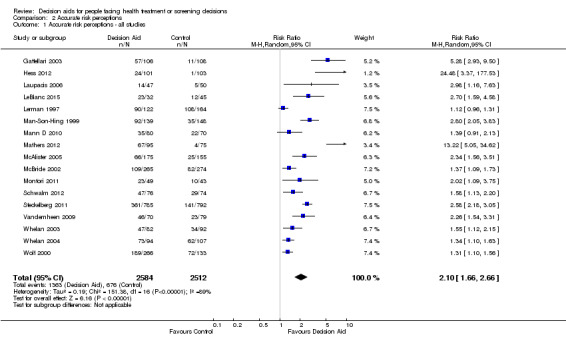

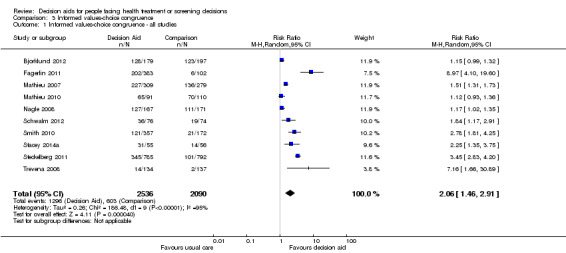

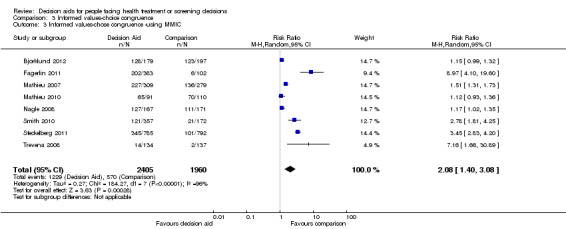

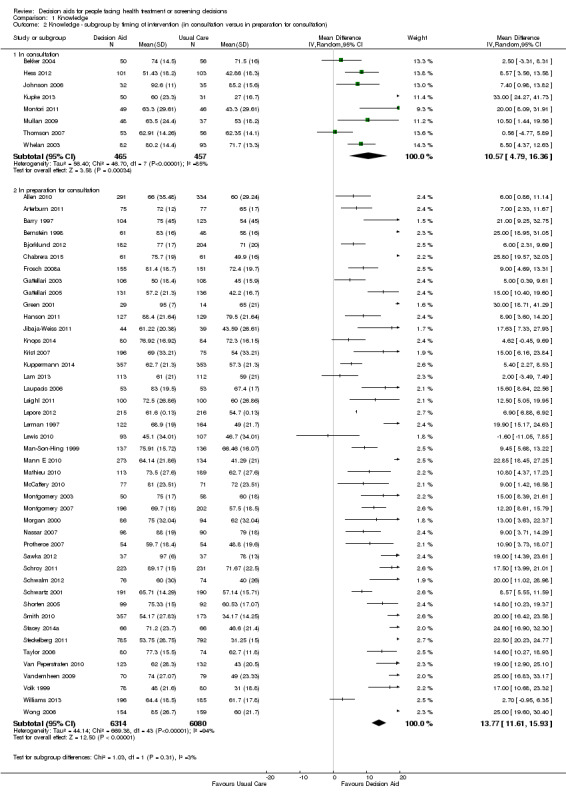

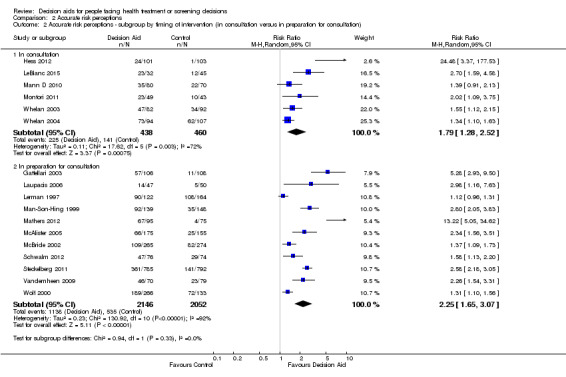

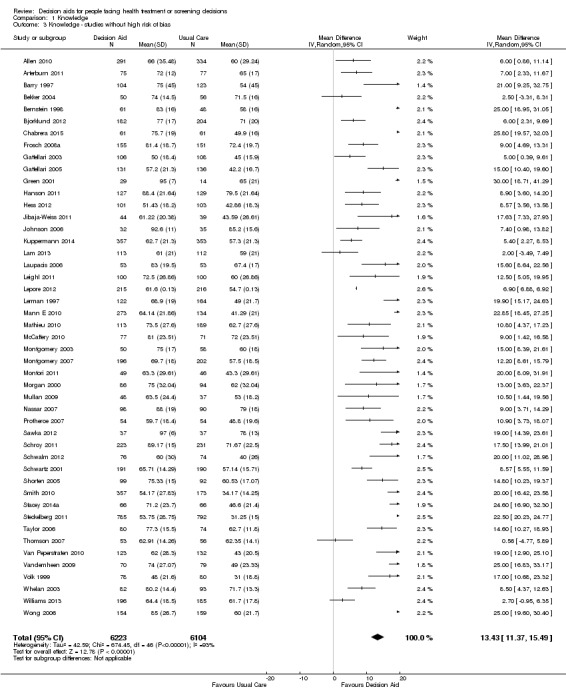

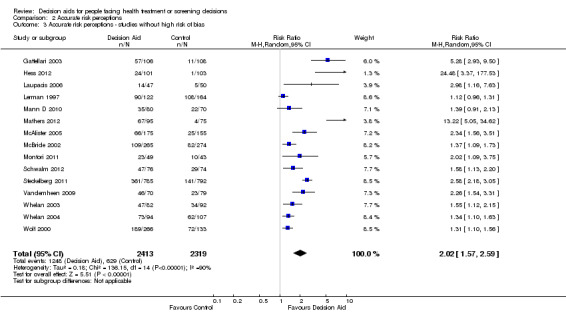

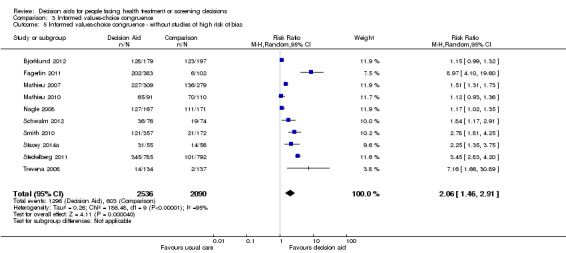

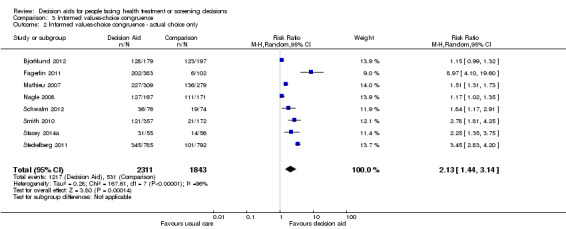

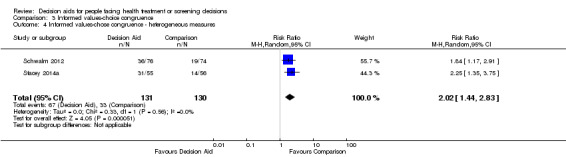

With regard to the attributes of the choice made, decision aids increased participants' knowledge (MD 13.27/100; 95% confidence interval (CI) 11.32 to 15.23; 52 studies; N = 13,316; high‐quality evidence), accuracy of risk perceptions (RR 2.10; 95% CI 1.66 to 2.66; 17 studies; N = 5096; moderate‐quality evidence), and congruency between informed values and care choices (RR 2.06; 95% CI 1.46 to 2.91; 10 studies; N = 4626; low‐quality evidence) compared to usual care.

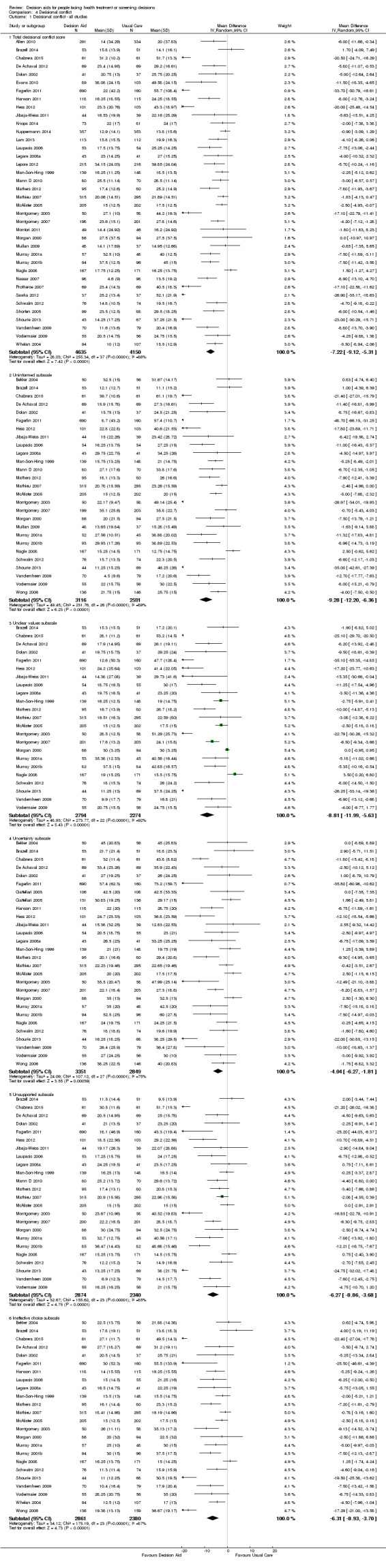

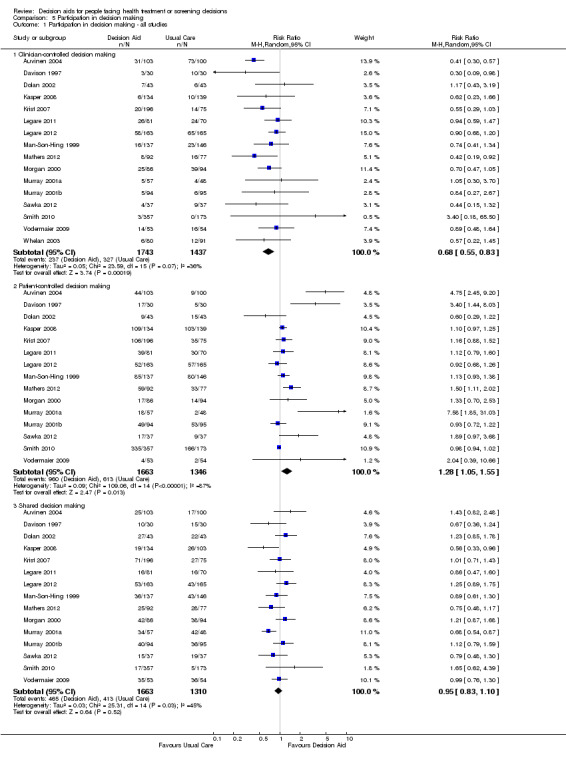

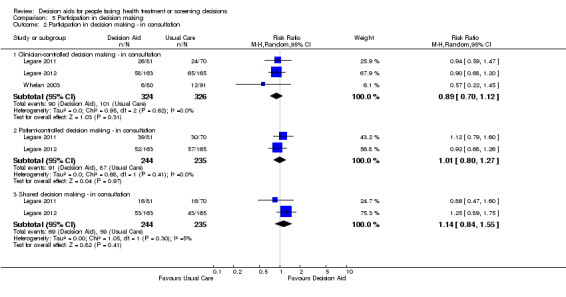

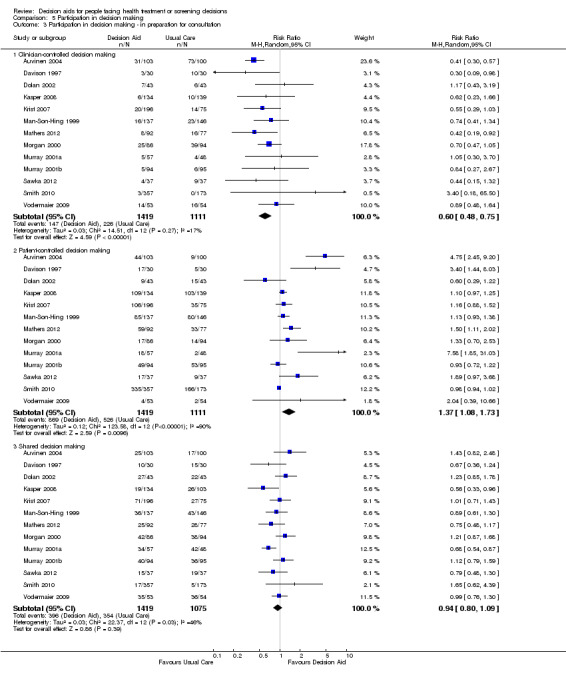

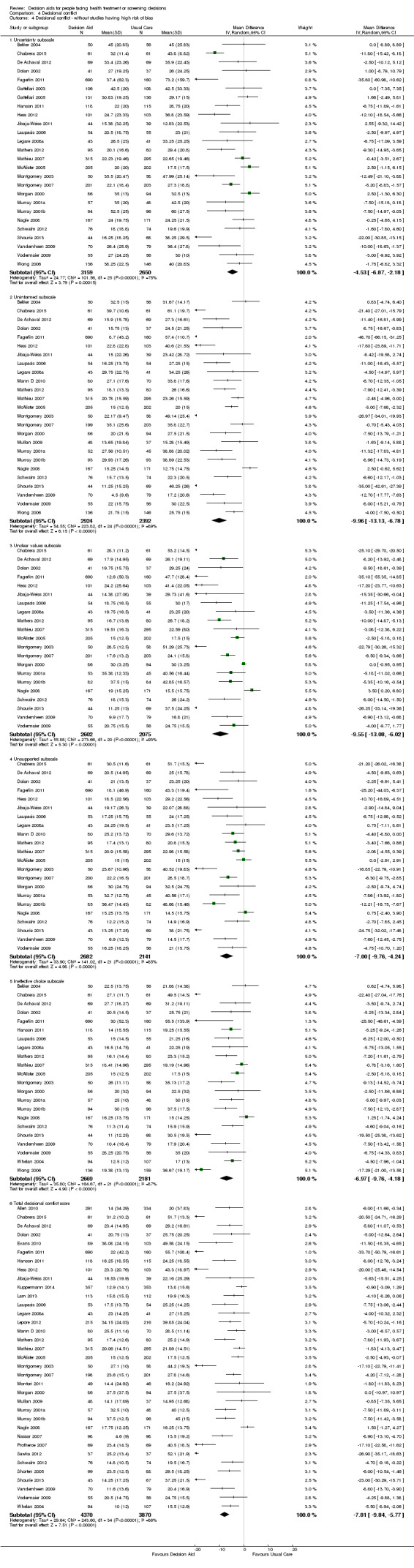

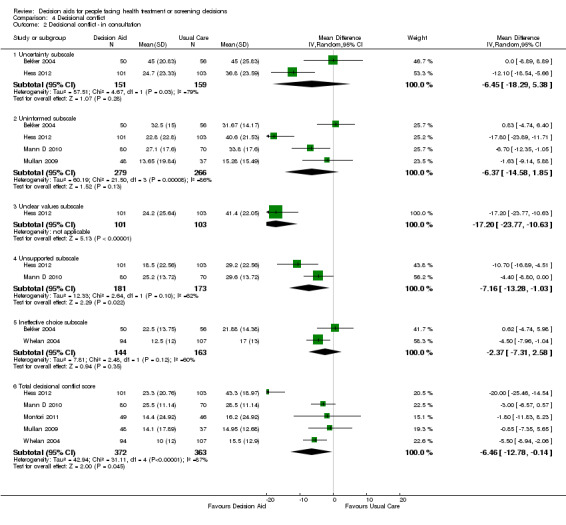

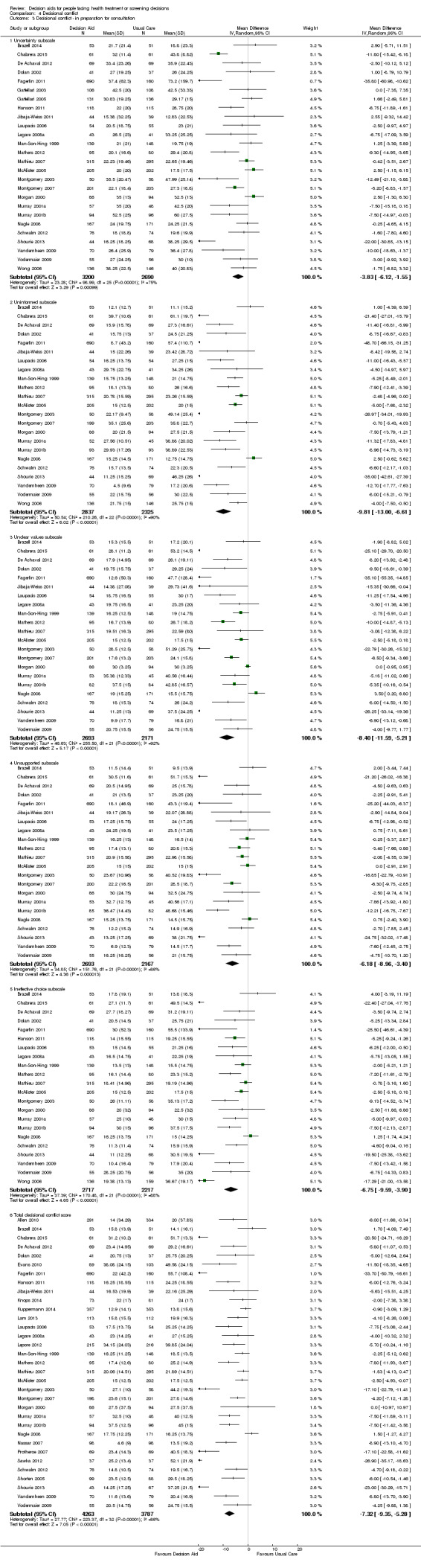

Regarding attributes related to the decision‐making process and compared to usual care, decision aids decreased decisional conflict related to feeling uninformed (MD −9.28/100; 95% CI −12.20 to −6.36; 27 studies; N = 5707; high‐quality evidence), indecision about personal values (MD −8.81/100; 95% CI −11.99 to −5.63; 23 studies; N = 5068; high‐quality evidence), and the proportion of people who were passive in decision making (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.83; 16 studies; N = 3180; moderate‐quality evidence).

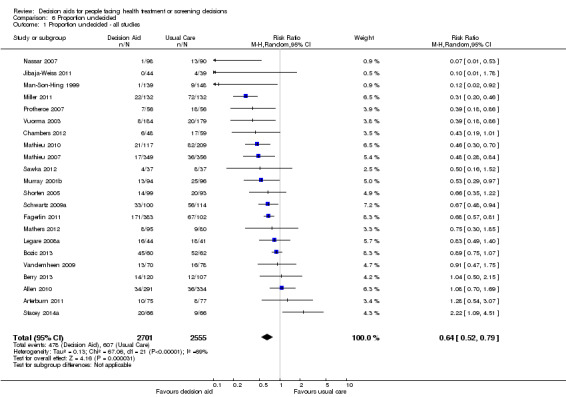

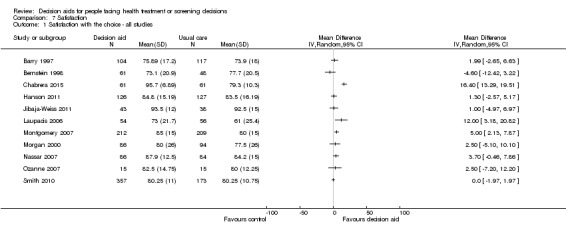

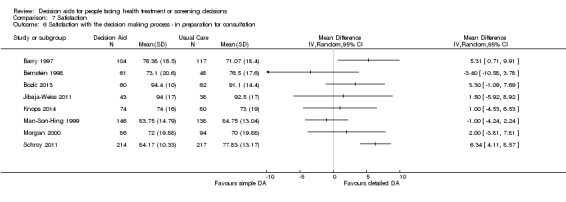

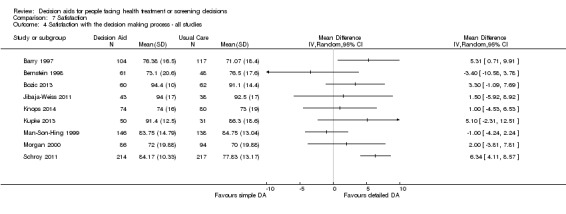

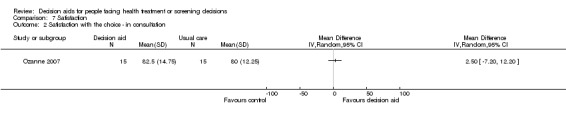

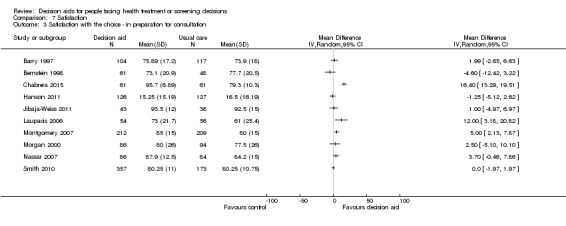

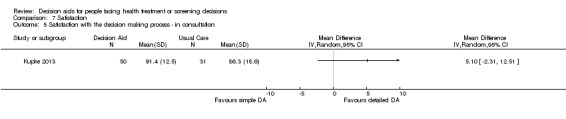

Decision aids reduced the proportion of undecided participants and appeared to have a positive effect on patient‐clinician communication. Moreover, those exposed to a decision aid were either equally or more satisfied with their decision, the decision‐making process, and/or the preparation for decision making compared to usual care.

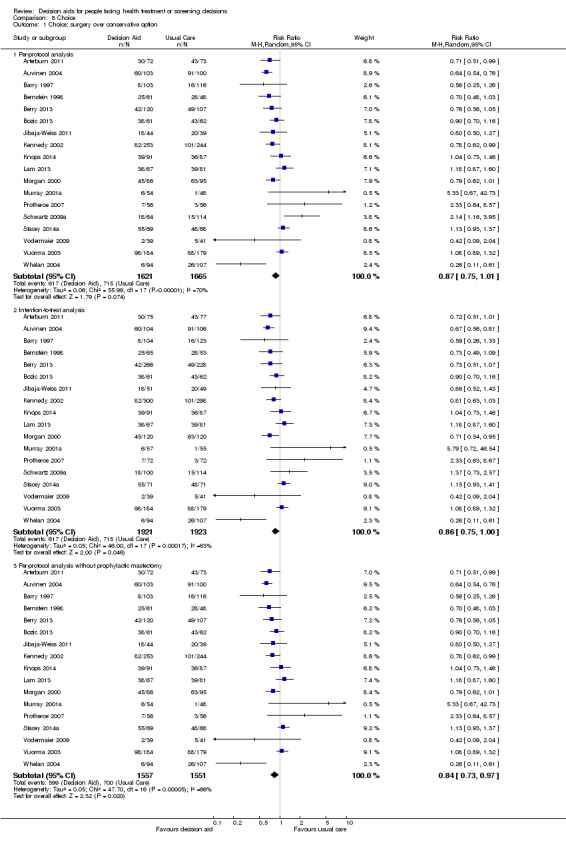

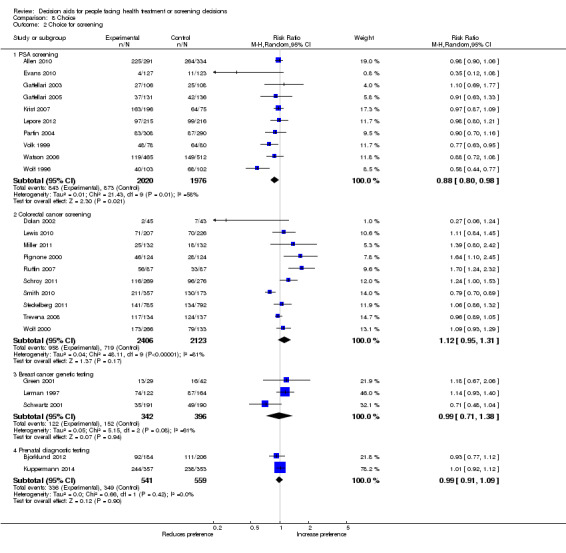

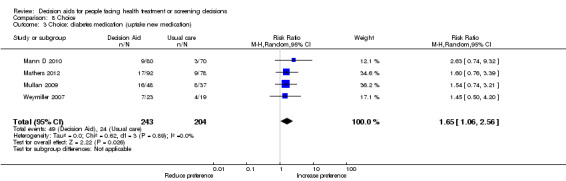

Decision aids also reduced the number of people choosing major elective invasive surgery in favour of more conservative options (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.00; 18 studies; N = 3844), but this reduction reached statistical significance only after removing the study on prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer gene carriers (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.73 to 0.97; 17 studies; N = 3108). Compared to usual care, decision aids reduced the number of people choosing prostate‐specific antigen screening (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.80 to 0.98; 10 studies; N = 3996) and increased those choosing to start new medications for diabetes (RR 1.65; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.56; 4 studies; N = 447). For other testing and screening choices, mostly there were no differences between decision aids and usual care.

The median effect of decision aids on length of consultation was 2.6 minutes longer (24 versus 21; 7.5% increase). The costs of the decision aid group were lower in two studies and similar to usual care in four studies. People receiving decision aids do not appear to differ from those receiving usual care in terms of anxiety, general health outcomes, and condition‐specific health outcomes. Studies did not report adverse events associated with the use of decision aids.

In subgroup analysis, we compared results for decision aids used in preparation for the consultation versus during the consultation, finding similar improvements in pooled analysis for knowledge and accurate risk perception. For other outcomes, we could not conduct formal subgroup analyses because there were too few studies in each subgroup.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to usual care across a wide variety of decision contexts, people exposed to decision aids feel more knowledgeable, better informed, and clearer about their values, and they probably have a more active role in decision making and more accurate risk perceptions. There is growing evidence that decision aids may improve values‐congruent choices. There are no adverse effects on health outcomes or satisfaction. New for this updated is evidence indicating improved knowledge and accurate risk perceptions when decision aids are used either within or in preparation for the consultation. Further research is needed on the effects on adherence with the chosen option, cost‐effectiveness, and use with lower literacy populations.

Plain language summary

Decision aids to help people who are facing health treatment or screening decisions

Review question

We reviewed the effects of decision aids on people facing health treatment or screening decisions. In this update, we added 18 new studies for a total of 105.

Background

Making a decision about the best treatment or screening option can be hard. People can use decision aids when there is more than one option and neither is clearly better, or when options have benefits and harms that people value differently. Decision aids may be pamphlets, videos, or web‐based tools. They state the decision, describe the options, and help people think about the options from a personal view (e.g. how important are possible benefits and harms).

Study characteristics

For research published up to April 2015, there were 105 studies involving 31,043 people. The decision aids focused on 50 different decisions. The common decisions were about: surgery, screening (e.g. prostate cancer, colon cancer, prenatal), genetic testing, and medication treatments (e.g. diabetes, atrial fibrillation).The decision aids were compared to usual care that may have included general information or no intervention. In the 105 studies, 89 evaluated a patient decision aid used by people in preparation for the visit with the clinician, and 16 evaluated its use during the visit with the clinician.

Key results with quality of the evidence

When people use decision aids, they improve their knowledge of the options (high‐quality evidence) and feel better informed and more clear about what matters most to them (high‐quality evidence). They probably have more accurate expectations of benefits and harms of options (moderate‐quality evidence) and probably participate more in decision making (moderate‐quality evidence). People who use decision aids may achieve decisions that are consistent with their informed values (evidence is not as strong; more research could change results). People and their clinicians were more likely to talk about the decision when using a decision aid. Decision aids have a variable effect on the option chosen, depending on the choice being considered. Decision aids do not worsen health outcomes, and people using them are not less satisfied. More research is needed to assess if people continue with the option they chose and also to assess what impact decision aids have on healthcare systems.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Patient decision aids compared with usual care for adults considering treatment or screening decisions | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults considering treatment or screening decisions Settings: all settings Intervention: patient decision aid Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative benefits* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed benefit | Corresponding benefit | |||||

| Usual care | Patient decision aid | |||||

|

Knowledge ‐ all studies Standardized on score from 0 (no knowledge) to 100 (perfect knowledge), soon after exposure to the decision aid |

The mean knowledge score was 56.9% across control groups, ranging from 27.0% to 85.2% | The mean knowledge score in the intervention groups was 13.27 higher (11.32 to 15.23 higher) | — | 13,316 (52 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b | Higher scores indicate better knowledge. 46 out of 52 studies showed a statistically significant improvement in knowledge |

|

Accurate risk perceptions ‐ all studies Assessed soon after exposure to the decision aid |

269 per 1000c | 565 per 1000 (447 to 716 per 1000) | RR 2.10 (1.66 to 2.66) | 5096 (17 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,d | — |

|

Congruence between the chosen option and informed values ‐ all studies Assessed soon after exposure to the decision aid |

289 per 1000c | 595 per 1000 (422 to 841 per 1000) | RR 2.06 (1.46 to 2.91) | 4626 (10 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d,e,f | — |

|

Decisional conflict: uninformed subscale ‐ all studies Standardized on score from 0 (not uninformed) to 100 (uninformed) Assessed soon after exposure to the decision aid |

The mean for outcome 'feeling uninformed' ranged across control groups from 11.1 to 61.1. Scores ≤ 25 associated with following through on decisions. Scores > 38 associated with delay in decision making |

The mean feeling uninformed in the intervention groups was 9.28 lower (12.20 to 6.36 lower) | — | 5707 (27 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b | Lower scores indicate feeling more informed |

|

Decisional conflict: unclear about personal values subscale ‐ all studies Standardized on score from 0 (not unclear) to 100 (unclear) Assessed soon after exposure to the decision aid |

The mean for outcome 'feeling unclear about personal values' ranged across control groups from 15.5 to 53.2. Scores ≤ 25 associated with follow‐through with decisions. Scores > 38 associated with delay in decision making |

The mean feeling unclear values in the intervention groups was 8.81 lower (11.99 to 5.63 lower) | — | 5068 (23 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b | Lower scores indicate feeling clearer about values |

|

Participation in decision making: clinician‐controlled decision making ‐ all studies Assessed soon after consultation with clinician |

228 per 1000c | 155 per 1000 (125 to 189 per 1000) | RR 0.68 (0.55 to 0.83) | 3180 (16 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,e | Patient decision aids aim to increase patient involvement in making decisions; lower proportion of clinician‐controlled decision making is better |

| Adverse events | There were no adverse effects on health outcomes or satisfaction, and no other adverse effects reported. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aThe vast majority of studies measuring this outcome were not at high risk of bias. bThe GRADE ratings for these outcomes were not downgraded for heterogeneity given the generally consistent direction of effects across studies for the decision aid compared to usual care groups. cThe data source for the assumed risk was the mean control event rate. dThe GRADE rating was downgraded given the lack of precision. eThe GRADE rating was downgraded given the lack of consistency. fThe GRADE rating was downgraded given the lack of directness. As well, the outcome was measured using various approaches with no gold standard approach.

Background

Many health treatment and screening decisions have no single 'best' choice. These types of decisions are considered 'preference‐sensitive' because there is insufficient evidence about outcomes or there is a need to trade off known benefits and harms. Clinical Evidence analyzed 3000 treatments, classifying 50% as having insufficient evidence, 24% as likely to be beneficial, 7% as requiring trade‐offs between benefits and harms, 5% as unlikely to be beneficial, 3% as likely to be ineffective or harmful, and only 11% as being clearly beneficial (Clinical Evidence 2013). Not only does one have to take into account the strength of the evidence, but even for the 11% of treatments that show beneficial effects for populations, physicians need to translate the probabilistic nature of the evidence for individual patients to help them reach a decision based on informed values. Patient decision aids are an intervention that can be used to present such evidence (Brouwers 2010). This review is an update of the review last published in 2014 of the comparisons between patient decision aids and usual care (Stacey 2014b). To provide a more focused review, we removed 28 studies that compared detailed versus simple decision aids.

Description of the intervention

According to the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration (Elwyn 2006; IPDAS 2005a; Joseph‐Williams 2013), decision aids are evidence‐based tools designed to help patients make specific and deliberated choices among healthcare options. Patient decision aids supplement (rather than replace) clinicians' counselling about options. The specific aims of decision aids and the type of decision support they provide may vary slightly, but in general they:

explicitly state the decision that needs to be considered;

provide evidence‐based information about a health condition, the options, associated benefits, harms, probabilities, and scientific uncertainties;

help patients to recognize the values‐sensitive nature of the decision and to clarify, either implicitly or explicitly, the value they place on the benefits and harms. (To accomplish this, patient decision aids may describe the options in enough detail that clients can imagine what it is like to experience the physical, emotional, and social effects, or they may guide clients to consider which benefits and harms are most important to them.)

Decision aids differ from usual health education materials. Decision aids make the decision being considered explicit, providing a detailed, specific, and personalized focus on options and outcomes for the purpose of preparing people for decision making. In contrast, health education materials help people to understand their diagnosis, treatment, and management in general terms, but given their broader perspective, these materials are not focused on decision points and thus do not necessarily help them to participate in decision making. Many decision aids are based on a conceptual model or theoretical framework (Durand 2008; Mulley 1995; O'Connor 1998b; Rothert 1987).

In response to concerns about variability in the quality of patient decision aids, the IPDAS Collaboration reached agreement on criteria for judging their quality (Elwyn 2006). More than 100 researchers, clinicians, patients, and policymakers from 14 countries participated. Participants addressed three domains of quality: clinical content, development process, and evaluation of a patient decision aid's effectiveness. A series of background papers informing the original IPDAS criteria were updated in 2013 (IPDAS 2013). Subsequently, an international team of researchers reached consensus on a shorter set of qualifying and certifying criteria (Joseph‐Williams 2013). Informed by IPDAS, the Washington State Health Authority launched the first programme for certifying patient decision aids in 2016 (Washington State 2016).

How the intervention might work

Decision aids can be used before, during, or after a clinical encounter to enable patients to become active, informed participants. Providing the patient decision aid in preparation for the consultation allows people more time to digest the information and be ready to discuss the decision, but this may not be feasible in some health decisions (e.g. antibiotics for upper respiratory infections). Decision aids can also facilitate shared decision making. Shared decision making is defined as a process through which clinicians and patients make healthcare choices together (Charles 1997; Makoul 2006), representing the crux of people‐centred care (Weston 2001). However, the way the clinician provides information may strongly affect people's preferences (Hibbard 1997), prompting the need for standardized information such as patient decision aids. Patients who are more active in making decisions about their health have better health outcomes and healthcare experiences (Hibbard 2013; Kiesler 2006). In summary, patient decision aids may help clinicians and patients come to quality decisions, grounded in patients' values and taking into account the potential trade‐offs in benefits and risks of different options.

Why it is important to do this review

Given the broad range of stakeholders interested in patient decision aids and the rapidly expanding field of research, there was a need to update this review to identify studies on new decisions or conducted in new countries and to strengthen the synthesized evidence supporting use of patient decision aids for outcomes that do not yet have high‐quality evidence. In fact, the 2014 publication was the most cited Cochrane Review in 2015 based on 1888 reviews published in 2013 and 2014. With growing development of patient decision aids for use in the consultation, we wanted to conduct a subgroup analysis of patient decision aids used in preparation for versus within the consultation.

Results from previous reviews were used to inform clinical practice guidelines such as Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services (NCGC/NICE 2012) and Decision Support for Adults Living with Chronic Kidney Disease (RNAO 2009). Subgroup analyses of included studies have focused on anxiety (Bekker 2003), adherence (Trenaman 2016), values congruence (Munro 2016), participant trial identity (Brown 2015), and heterogeneity (Gentles 2013).

Other systematic reviews have been conducted on the use of patient decision aids as one type of intervention to facilitate shared decision making in clinical practice (Coyne 2013; Duncan 2010; Elwyn 2013; Legare 2010; Legare 2014).

Objectives

To assess the effects of decision aids in people facing treatment or screening decisions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all published studies that used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design evaluating patient decision aids.

Types of participants

We included studies involving adults aged 18 years or older who were making decisions about screening or treatment options for themselves, a child, or an incapacitated significant other. We excluded studies in which participants were making hypothetical choices.

Types of interventions

We included studies that evaluated a patient decision aid as part of the intervention. Decision aids were defined as interventions designed to help people make specific and deliberated choices among options (including the status quo), by making the decision explicit and by providing (at the minimum) information on the options and outcomes relevant to a person's health status as well as implicit methods to clarify values. The aid also may have included: information on the disease/condition; costs associated with options; probabilities of outcomes tailored to personal health risk factors; an explicit values clarification exercise; information on others' opinions; a personalized recommendation on the basis of clinical characteristics and expressed preferences; and guidance or coaching in the steps of making and communicating decisions with others.

We excluded studies if interventions focused on: decisions about lifestyle changes, clinical trial entry, or general advance directives (e.g. do not resuscitate); education programmes not geared to a specific decision; and interventions designed to promote adherence or elicit informed consent regarding a recommended option. We also excluded studies when the relevant decision aid(s) were not available to us and not adequately described in the article(s), because we could not determine the aids’ characteristics and whether or not they met the minimum criteria to qualify as patient decision aids.

Types of comparisons

We included studies that compared patients exposed to a patient decision aid to patients in comparison groups that were exposed to usual care, general information, clinical practice guideline, placebo intervention, or no intervention. For the purposes of this review, we refer to all such control comparisons as 'usual care'.

We excluded studies that compared two different types of patient decision aids.

Types of outcome measures

To ascertain whether the decision aids achieved their objectives, we examined a broad range of outcomes. Although the decision aids focused on diverse clinical decisions, many had similar objectives such as improving knowledge scores, the accuracy of risk perceptions, and participation in decision making. Many of these evaluation criteria mapped onto the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of decision aids (Elwyn 2006; IPDAS 2005b; Sepucha 2013). The IPDAS criteria were attributes related to the choice (e.g. match between the chosen option and the features that matter most to the informed patient) and to the decision‐making process (e.g. helps patients to recognize that a decision needs to be made; know the options and their features; understand that values affect the decision; be clear about the features that matter most; discuss values with their clinician; and become involved in their preferred ways). A complete list of outcomes, specified in advance of the review, included primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Evaluation criteria that map onto the IPDAS criteria

Attributes of the choice made: does the patient decision aid improve the match between the chosen option and the features that matter most to the informed patient (demonstrated by outcomes such as knowledge, accurate risk perceptions, values‐choice congruence)?

Attributes of the decision‐making process: does the patient decision aid help patients to recognize that a decision needs to be made, feel informed about the options and their features, be clear about the option features that matter most, discuss values with their clinician, and become involved in decision making?

Other decision‐making process variables

Decisional conflict

Patient‐clinician communication

Participation in decision making

Proportion undecided

Satisfaction with the choice, with the process of decision making, and with the preparation for decision making

Secondary outcomes

Behaviour

Choice (the actual choice implemented; if not reported, the participants’ preferred option was used as a surrogate measure)

Adherence to chosen option

Health outcomes

Health status and quality of life (generic and condition‐specific)

Anxiety, depression, emotional distress, regret, confidence

Healthcare system

Costs, cost‐effectiveness

Consultation length

Litigation rates

Search methods for identification of studies

Our search strategy for the review included:

searching electronic medical and social science databases; and

searching other resources.

Electronic searches

For this update, we used the same search strategy that was revised by the Trials Search Coordinator at the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group in the last update (Stacey 2014b).

Therefore, the cumulative search of electronic databases is as follows.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library (searched to 24 April 2015).

MEDLINE Ovid (1966 to 24 April 2015).

Embase Ovid (1980 to 24 April 2015).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 24 April 2015).

CINAHL Ovid (1982 to September 2008), then in Ebsco (to 24 April 2015).

We present the search strategies in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

On 18 December 2015 we also searched trial registries (World Health Organization, ClinicalTrials.gov), the Internet using Google and Google Scholar, and the Decision Aid Library Inventory (decisionaid.ohri.ca). Finally, reference lists of all newly included trials were searched.

Data collection and analysis

For this current update, we focused only on new publications that had appeared since the previous publication (Stacey 2014b), and we limited the inclusion to patient decision aids versus usual care. As such, we removed studies from the previous reviews that compared detailed versus simple patient decision aids to provide a more focused review.

Selection of studies

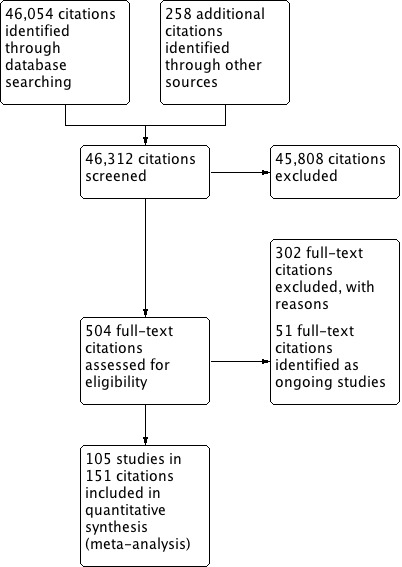

Pairs of eight review authors (CB, DS, RT, MB, MHR, KE, NC, DR) screened all identified citations. We retrieved the full text of any papers identified as potentially relevant by at least one author, listing all papers excluded from the review at this stage, with reasons, in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We also provided citation details and any available information about ongoing studies, and we collated and reported details of additional publications, so that each study (rather than each report) was the unit of interest. We report the screening and selection process in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two research assistants extracted data independently (KL, IS). We compared findings and resolved inconsistencies through discussion with the principal investigator (DS) and, when necessary, with a co‐author (CB). No review authors extracted data for their own studies in this update nor in any other versions of this review.

One review author entered all extracted data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5), and a second one worked independently to check for accuracy against the data extraction sheets (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two research assistants independently appraised studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (current update: KL, IS) (Higgins 2011, Chapter 8). We judged each item as conferring high, low, or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria provided by Higgins 2011, and we provided a quote from the study report and a justification for our judgement for each item in the 'Risk of bias' table. For the item on 'other' potential sources of bias, the assessment included: whether the same clinician provided consultation to both the intervention and usual care groups with measures taken postconsultation, whether clustering was accounted for in the analysis; and potential sources of bias reported by the authors in the study limitations.

We resolved inconsistencies by discussion with the principal investigator (DS) and, when necessary, with a co‐author (CB). No review authors appraised risk of bias for their own studies in this update nor in any other versions of this review.

Studies were deemed to be at the highest risk of bias if they were scored as at high risk on any of the items of the risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we analyzed data based on the number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups. We will use these to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous measures, we analyzed data based on the mean, standard deviation (SD) and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups to calculate mean difference (MD) and 95% CI.

First, we described study characteristics individually. The a priori comparison was usual care versus decision aids. For studies in which there were more than one intervention group, we extracted data from the groups that provided the strongest contrast between the intervention and control groups. We pooled results across studies in cases where investigators used similar outcome measures and the effects were expected to be independent of the type of decision studied. For example, we expected decision aids to improve knowledge and create accurate percetions of options, benefits, and harms; to reduce decisional conflict; and to enhance active participation in decision making. Therefore, we pooled data from included RCTs for these outcomes if trials used comparable measures. To facilitate pooling of data for some outcomes (e.g. knowledge, decisional conflict), we standardized the scores to range from 0 to 100 points. When analysing the effects of decision aids on choices, we pooled outcomes on more homogeneous subgroups of decisions (choice of major surgery versus conservative options; screening test or not, etc.).

Unit of analysis issues

We checked for unit‐of‐analysis errors. Where we found errors and sufficient information was available, we re‐analyzed the data using the appropriate unit of analysis by taking account of the intracluster correlation (ICC). We obtained estimates of the ICC by contacting authors of included studies, or we imputed them using estimates from external sources. For two studies (Kupke 2013; Lewis 2010), it was not possible to obtain sufficient information to re‐analyze the data, and we reported these studies as being at high risk for 'other' bias based on these unit‐of‐analysis errors. We made no adjustments to the data based on these two studies that were included in meta‐analysis for knowledge only.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors to obtain missing data. Where possible, we conducted analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis; otherwise, we analyzed data as reported. We reported on the levels of loss to follow‐up and assessed this as a source of potential bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For this update and in previous versions of the review, we grouped studies together across populations and settings. The aim was to enable an assessment of the effectiveness of decision aids across conditions, rather than to focus on disease‐specific contexts. Given that decision aids are a well‐defined and clearly delineated type of intervention, we decided that this approach was defensible. On the basis of grouping studies across populations and decision aid elements, we anticipated that there would be a substantial degree of heterogeneity in our pooled effect estimates. However, we decided that we would consider the direction of effects and variability in these rather than variability in the size of effects, as the major basis for our interpretation of heterogeneity. This meant that for those pooled effect estimates where the direction of effect was consistent across studies, we did not downgrade for inconsistency, despite some variability in the size of effects across individual studies. We did downgrade for inconsistency for one outcome: congruence between the chosen option and informed values. This was because there is no accepted gold standard measure for assessing this outcome, and we considered that variability in measurement by the included studies added further uncertainty about the effects of decision aids for this outcome.

Where heterogeneity was present in pooled effect estimates, we explored possible reasons for variability by conducting subgroup analysis in the 2009 update (O'Connor 2009b). The post hoc analysis included the IPDAS effectiveness criteria to explore heterogeneity according to the following factors: the type of decision (treatment versus screening), the type of media of the decision aid (video/computer versus audio booklet/pamphlet), and the possibility of a ceiling effect based on usual‐care scores (resulting in the removal of studies with lower scores for knowledge and accurate risk perception and higher scores for decisional conflict using the subscales measuring levels of informedness and clarity of values). We analyzed the effect of removing the biggest outlier(s) (defined by visual inspection of forest plots). Given that the post hoc analysis did not alter the findings from the 2009 update, we did not re‐conduct the post hoc analysis for the IPDAS effectiveness criteria.

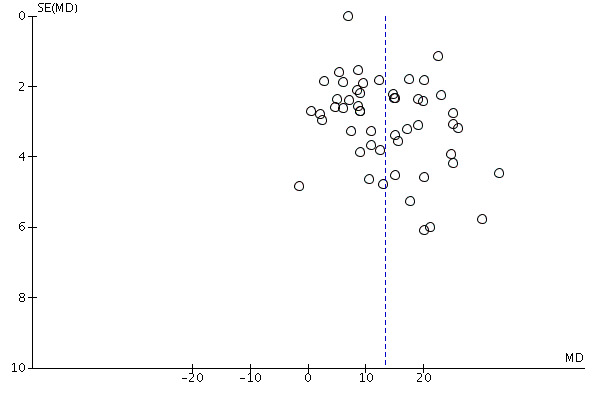

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

We used RevMan 5 software to estimate a weighted intervention effect with 95% confidence intervals (RevMan 2014). For continuous measures, we used mean differences (MD); for dichotomous outcomes, we calculated pooled relative risks (RR). We analyzed all data with a random‐effects model because of the diverse nature of the studies being combined and then anticipated variability in the populations and interventions of the included studies. We summarized all of the results for the primary outcomes and rated the strength of evidence using GRADE (Andrews 2013), presenting these in a 'Summary of findings' table (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For this update, we conducted a subgroup analysis to compare the effects of the intervention when used in preparation for the consultation with the effects of those used during the consultation to usual care.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed post hoc sensitivity analyses to examine the effect of excluding studies of lower methodological quality. The analysis excluded studies that were at high risk of bias for any of the categories in the 'Risk of bias' assessment (Higgins 2011).

'Summary of findings' table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table to present the results of meta‐analysis, based on the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We presented the results of meta‐analysis for the major comparison of the review for each of the key outcomes. We provided a source and rationale for each assumed risk cited in the table and used the GRADE criteria to rank the quality of the evidence for each outcome on each of the following domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. Two authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro) software (GRADEpro GDT).

Results

Description of studies

The current version of our review updates our 2014 version, Stacey 2014b, with 18 new studies (Bozic 2013; Brazell 2014; Chabrera 2015; Fraenkel 2012; Knops 2014; Köpke 2014; Kuppermann 2014; Lam 2013; LeBlanc 2015; Legare 2012; Lepore 2012; Mathers 2012; Mott 2014; Sawka 2012; Shourie 2013; Stacey 2014a; Taylor 2006; Williams 2013). For this update, we excluded 28 previously included studies due to the comparisons being limited to detailed versus simple patient decision aids (Deschamps 2004; Deyo 2000; Dodin 2001; Goel 2001; Green 2004; Hunter 2005; Kuppermann 2009; Labrecque 2010; Lalonde 2006; Legare 2003; Leung 2004; Myers 2005a; Myers 2011; O'Connor 1998a; O'Connor 1999a; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Rostom 2002; Rothert 1997; Schapira 2000; Schapira 2007; Solberg 2010; Street 1995; Tiller 2006; Van Roosmalen 2004; Volk 2008; Wakefield 2008a; Wakefield 2008b; Wakefield 2008c).

Results of the search

In total, we identified 46,054 citations from the electronic database searches and 258 citations from other sources. Of these, we assessed 504 citations for eligibility using the full text (see Figure 1).

Included studies

The remaining 151 citations provided data on 105 studies that met our inclusion criteria, 18 of which are new for this update. The 105 RCTs, involving 31,043 participants, presented results from 10 countries: Australia (10 studies), Canada (15 studies), China (1 study), Finland (2 studies), Germany (6 studies), Netherlands (2 studies), Spain (1 study), Sweden (1 study), the UK (16 studies), the USA (50 studies), and Australia plus Canada (1 study). We present study details below and in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Unit of randomization

Ninety studies randomized individual patients, and 15 randomized clusters. For cluster trials, Allen 2010 randomized 12 company worksites; Fraenkel 2012, 2 groups of primary care physicians; Hamann 2006, 12 inpatient psychiatric units; Kupke 2013, 49 dental students; Legare 2011, 4 family medicine group practices; Legare 2012, 12 family medicine group practices; Lewis 2010, 32 family medicine group practices; Loh 2007, 30 general practitioners; Mathers 2012, 49 general medicine practices; McAlister 2005, 102 primary care practices; Mullan 2009, 40 clinicians; Nagle 2008, 60 general practitioners; Shourie 2013, 50 general medicine practices; Weymiller 2007, 21 endocrinologists; and Whelan 2004, 27 surgeons.

For 10 studies (Allen 2010; Legare 2011; Legare 2012; Loh 2007; Mathers 2012; Mullan 2009; Nagle 2008; Shourie 2013; Weymiller 2007; Whelan 2004), the cluster effect was taken into account in the published outcome data, and the meta‐analysis used published results. Although Hamann 2006 did not account for the cluster effect in the published outcome data, the way this study was reported did not allow us to include it in the meta‐analysis, so we did not re‐analyze the data and report the study separately. For McAlister 2005, meta‐analysis was done applying the design effect (based on the published intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC)). For Fraenkel 2012, the authors stated that adding a random effect for physician clusters did not contribute to better‐fitting regression models, and we removed it from the analysis. The analysis by Kupke 2013 and Lewis 2010 did not account for clustering.

Decision aids and comparisons

The 105 included studies evaluated decision aids that focused on 50 different decisions (Table 2). The most common decisions were about prostate cancer screening (14 studies), colon cancer screening (10 studies), medication for diabetes (4 studies), breast cancer genetic testing (4 studies), prenatal screening (4 studies), medication for atrial fibrillation (4 studies), and surgery (mastectomy for breast cancer, 4 studies; hysterectomy, 3 studies; prostate cancer treatment, 4 studies). New decision topics added in this update included surgery for prolapsed pelvic organs (1 study) and asymptomatic aortic abdominal aneurysm (1 study); restoration for tooth decay (1 study); measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine for infants (1 study); treatment of post‐traumatic stress disorder (1 study); and radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer (1 study).

1. Decision aids evaluated in the trials.

| Study | Topic | Availability | Source | Contact Information |

| Allen 2010 | Prostate cancer screening | No | Allen, Center for Community‐Based Research, Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA, 2010 | Requested access |

| Arterburn 2011 | Bariatric surgery | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA,USA, 2010 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/making‐decisions‐about‐weight‐loss‐surgery/ |

| Auvinen 2004 | Prostate cancer treatment | Yes | Auvinen, Helsinki, Finland, 1993 | Included in publication |

| Barry 1997 | Benign prostate disease treatment | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA, USA, 2001 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐options‐for‐benign‐prostatic‐hyperplasia/ |

| Bekker 2004 | Prenatal screening | Yes | Bekker, Leeds, UK, 2003 | Included in publication |

| Bernstein 1998 | Ischaemic heart disease treatment | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA,USA, 2002 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐choices‐for‐carotid‐artery‐disease/ |

| Berry 2013 | Prostate cancer treatment | No | Berry, Phyllis F. Cantor Center, MA, USA, 2011 | donna_berry@dfci.harvard.edu |

| Bjorklund 2012 | Antenatal Down syndrome screening | Yes | Södersjukhuset, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stockholm, Sweden | vimeo.com/34600615/ |

| Bozic 2013 | Osteoarthritis of the knee or hip | No | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation and Health Dialog; USA | www.healthdialog.com |

| Brazell 2014 | Pelvic Organ Prolapse | Yes | Healthwise, USA | decisionaid.ohri.ca |

| Chabrera 2015 | Prostate cancer treatment | No | C Chabrera. School of Health Sciences, Department of Nursing. Mataro, Spain | cchabrera@tecnocampus.cat |

| Chambers 2012 | Healthcare personnel’s influenza immunization | Yes | A McCarthy. Ottawa Influenza Decision Aid Planning Group, CA, 2008 | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids.html#oida |

| Clancy 1988 | Hepatitis B Vaccine | No | Clancy, Richmond VA, USA, 1983 | — |

| Davison 1997 | Prostate cancer treatment | No | Davison, Manitoba CA, 1992‐1996 | — |

| De Achaval 2012 | Total knee arthroplasty treatment | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA,USA | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐choices‐for‐knee‐osteoarthritis/ |

| Dolan 2002 | Colon cancer screening | No | Dolan, Rochester NY, USA, 1999 | — |

| Evans 2010 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Elwyn, Cardiff, UK | www.prosdex.com |

| Fagerlin 2011 | Breast cancer prevention | Yes | Fagerlin, Ann Arbor, MI, USA | — |

| Fraenkel 2007 | Osteoarthritis knee treatment | No | Fraenkel, New Haven CT, USA | Author said DA never fully developed, all info in paper |

| Fraenkel 2012 | Atrial fibrillation | No | Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, USA | Obtained from author terri.fried@yale.edu |

| Frosch 2008a | Prostate cancer screening | No | Frosch, Los Angeles, USA | Screenshots from author |

| Gattellari 2003 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Gatellari, Sydney, AU, 2003 | included in publication |

| Gattellari 2005 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Gatellari, Sydney, AU, 2003 | Included in publication |

| Green 2001 | Breast cancer genetic testing | Yes | Green, Hershey PA, USA, 2000 | 1‐800‐757‐4868 dwc@mavc.com |

| Hamann 2006 | Schizophrenia treatment | Yes | Hamann, Munich, GER | Emailed by author (in German) |

| Hanson 2011 | Feeding options in advanced dementia | Yes | Mitchell, Tetroe, O'Connor; 2001 (updated 2008) | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids.html#feedingtube |

| Heller 2008 | Breast reconstruction | Yes | University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX, USA, 2003 | Disc mailed |

| Hess 2012 | Stress testing for chest pain | Yes | Hess, Rochester, MN, USA, 2012 | Included in publication |

| Jibaja‐Weiss 2011 | Breast cancer treatment | Yes | Jibaja‐Weiss, Baylor College of Medicine, 2010 | www.bcm.edu/patchworkoflife |

| Johnson 2006 | Endodontic treatment | Yes | Johnson, Chicago, USA, 2004 | Included in publication |

| Kasper 2008 | Multiple sclerosis | No | Jürgen Kasper | — |

| Kennedy 2002 | Abnormal uterine bleeding treatment | No | Kennedy/Coulter, London UK, 1996 | — |

| Knops 2014 | Asymptomatic Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm treatment | Yes | Amsterdam, The Netherlands | www.keuzehulp.info/amc/AAA/landing‐page |

| Krist 2007 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Krist, Fairfax VA, USA | www.familymedicine.vcu.edu/research/misc/psa/index.html |

| Kupke 2013 | Dental ‐ posterior tooth decay | Yes | University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany | jana.kupke@uk‐koeln.de |

| Kuppermann 2014 | Prenatal screening | No | Kuppermann, San Francisco CA, USA | Interactive web‐based decision aid |

| Lam 2013 | Breast cancer treatment | Yes | Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong, China | Obtained from author. wwtlam@hku.hk |

| Langston 2010 | Contraceptive method choice | Yes | World Health Organization, 2005 | www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9241593229index/en/index.html |

| Laupacis 2006 | Pre‐operative autologous blood donation | No | Laupacis, Ottawa, CA, 2001 | Decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids‐archive.html |

| LeBlanc 2015 | Treatment for osteoporosis | Yes | Mayo Clinic | — |

| Legare 2008a | Natural health products | No | Legare, Quebec City, CA, 2006 | — |

| Legare 2011 | Use of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections | Yes | Legare, Quebec City, CA, 2007 | www.decision.chaire.fmed.ulaval.ca/index.php?id=192&L=2 |

| Legare 2012 | Antibiotics for acute respiratory infections | Yes | Legare, Quebec City, CA | www.decision.chaire.fmed.ulaval.ca/index.php? |

| Leighl 2011 | Advanced colorectal cancer chemotherapy | Yes | Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, 2011 | Natasha.Leighl@uhn.on.ca |

| Lepore 2012 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Sally Weinrich University of Louisville, USA | Obtained from author slepore@temple.edu |

| Lerman 1997 | Breast cancer genetic testing | No | Lerman/Schwartz, Washington DC, USA, 1997 | — |

| Lewis 2010 | Colorectal cancer screening | Yes | Lewis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2010 | decisionsupport.unc.edu/CHOICE6/ |

| Loh 2007 | Depression treatment | Yes | Loh, Freiburg, GER | Emailed to us by author ‐ in German |

| Man‐Son‐Hing 1999 | Atrial fibrillation treatment | No | McAlister/Laupacis, Ottawa CA, 2000 | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids‐archive.html |

| Mann D 2010 | Diabetes treatment ‐ statins | Yes | Montori, Rochester MN, USA | mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/ker_unit/form.cfm |

| Mann E 2010 | Diabetes screening | Yes | Marteau, King's College London, London, England, 2010 | Additional file 2 of publication |

| Marteau 2010 | Diabetes screening | Yes | Marteau, King's College London, London, England, 2010 | Provided by author, same DA as Mann E 2010 |

| Mathieu 2007 | Mammography | Yes | Mathieu, Sydney, AU | DA emailed by author |

| Mathers 2012 | Diabetes treatment | Yes | The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2008 | Obtained from author C.Ng@sheffield.ac.uk |

| Mathieu 2010 | Mammography | Yes | Mathieu, University of Sydney, AUS, 2010 | www.psych.usyd.edu.au/cemped/com_decision_aids.shtml |

| McAlister 2005 | Atrial fibrillation treatment | No | McAlister/Laupacis, Ottawa CAN, 2000 | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids‐archive.html |

| McBride 2002 | Hormone replacement therapy | Yes, update in progress | Sigler/Bastien, Durham NC, USA, 1998 | basti001@mc.duke.edu |

| McCaffery 2010 | Screening after mildly abnormal pap smear | Yes | Screening & test evaluation program, School of public health, University of Sydney 2007 | kirstenm@health.usyd.edu.au |

| Miller 2005 | BRCA1/BRCA2 gene testing | No | Miller, Fox Chase PA, USA | — |

| Miller 2011 | Colorectal cancer screening | Yes | University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2007 | intmedweb.wakehealth.edu/choice/choice.html (no longer available) |

| Montgomery 2003 | Hypertension treatment | No | Montgomery, UK, 2000 | — |

| Montgomery 2007 | Birthing options after caesarean | Yes | Montgomery, Bristol, UK, last update 2004 | www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/acstaff/cjones/diamond/Information.html |

| Montori 2011 | Osteoporosis treatment | Yes | Montori, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2007 | shareddecisions.mayoclinic.org/decision‐aids‐for‐diabetes/other‐decision‐aids/ |

| Morgan 2000 | Ischaemic heart disease treatment | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA, USA, 2002 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐choices‐for‐carotid‐artery‐disease/ |

| Mott 2014 | PTSD treatment | Yes | Michael E DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Houston, USA | Obtained from author juliette.mott@va.gov |

| Mullan 2009 | Diabetes treatment | Yes | Montori or Mayo Foundation(?) Rochester MN, USA, | Included in publication |

| Murray 2001a | Benign prostate disease treatment | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA, USA, 2001 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐options‐for‐benign‐prostatic‐hyperplasia/ |

| Murray 2001b | Hormone replacement therapy | No, update in progress | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA, USA | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/treatment‐choices‐for‐managing‐menopause/ |

| Nagle 2008 | Prenatal screening | Yes | Nagle, Victoria, AU | www.mcri.edu.au/Downloads/PrenatalTestingDecisionAid.pdf |

| Nassar 2007 | Birth breech presentation | Yes | Nassar, West Perth WA, AU | sydney.edu.au/medicine/public‐health/shdg/resources/decision_aids.php |

| Oakley 2006 | Osteoporosis treatment | No | Cranney, Ottawa CA, 2002 | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids‐archive.html |

| Ozanne 2007 | Breast cancer prevention | No | Ozanne, Boston MA, USA | — |

| Partin 2004 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA,USA, 2001 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/deciding‐if‐the‐psa‐test‐is‐right‐for‐you/ |

| Pignone 2000 | Colon cancer screening | Yes | Pignone, Chapel Hill NC, USA, 1999 | www.med.unc.edu/medicine/edusrc/colon.htm |

| Protheroe 2007 | Menorrhagia treatment | No | Protheroe, Manchester, UK | Computerized decision aid, Clinical Guidance Tree ‐ no longer in existence, author sent chapter in thesis |

| Rubel 2010 | Prostate cancer screening | No | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), USA, 2010 | No longer available |

| Ruffin 2007 | Colorectal cancer screening | Yes | Regents of the University of Michigan (copyright info), Ann Arbor MI, USA, 2006 | colorectalweb.org |

| Sawka 2012 | Adjuvant radioactive iodine treatment for patients with early‐stage papillary thyroid cancer | No | University Health Network, Toronto, Canada, 2009 | — |

| Schroy 2011 | Colorectal cancer screening | Yes | Schroy III, Boston, USA | Paul.schroy@bmc.org |

| Schwalm 2012 | Coronary angiogram access site | Yes | Schwalm, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2009 | www.phri.ca/workfiles/studies/presentations/PtDA%20Vascular%20Access%2023‐May−2012.pdf |

| Schwartz 2001 | Breast cancer genetic testing | No | Schwartz/Lerman, Washington DC, USA, 1997 | — |

| Schwartz 2009a | BRCA mutation prophylactic surgery | No | Schwartz, Washington DC, USA | — |

| Sheridan 2006 | Cardiovascular prevention | Yes | Sheridan, Chapel Hill, NC, USA | www.med‐decisions.com/cvtool/ |

| Sheridan 2011 | Coronary heart disease prevention | Yes | Sheridan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Division of General Internal Medicine, North Carolina, USA, 2011 | www.med‐decisions.com/h2hv3/ |

| Shorten 2005 | Birthing options after previous caesarean | Yes (updated 2006) | Shorten, Wollongong, AU, 2000 | ashorten@uow.edu.au or www.capersbookstore.com.au/product.asp?id=301 |

| Shourie 2013 | Measles mumps and rubella vaccination | Yes | University of Leeds, UK & NSIRS Australia | www.leedsmmr.co.uk |

| Smith 2010 | Bowel cancer screening | Yes | Smith, Sydney, AU 2008 | sydney.edu.au/medicine/public‐health/shdg/resources/decision_aids.php |

| Stacey 2014a | Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee | No | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation and Health Dialog; USA | www.healthdialog.com |

| Steckelberg 2011 | Colorectal cancer screening | Yes | Steckelberg, Hamburg, Germany | — |

| Taylor 2006 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington DC, USA, 2000 | Obtained from author taylorkl@georgetown.edu |

| Thomson 2007 | Atrial fibrillation treatment | Yes | Thomson, Newcastle Upon Thyne, UK | Disc sent by mail |

| Trevena 2008 | Colorectal cancer screen | Yes | Trevena, Sydney, AU | sydney.edu.au/medicine/public‐health/shdg/resources/decision_aids.php |

| Van Peperstraten 2010 | Embryos transplant | Yes | Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre; 2006 | www.umcn.nl/ivfda‐en |

| Vandemheen 2009 | Cystic Fibrosis referral transplant | Yes | Aaron, Ottawa ON, CA, 2009 (last update 2011) | decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids.html#cfda |

| Vodermaier 2009 | Breast cancer surgery | Yes | Vodermaier, Vancouver BC, CA | Received by email (in German) |

| Volk 1999 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, MA, USA, 1999 | informedmedicaldecisions.org/imdf_decision_aid/deciding‐if‐the‐psa‐test‐is‐right‐for‐you/ |

| Vuorma 2003 | Menorrhagia treatment | No | Vuorma, Helsinki Finland, 1996 | — |

| Watson 2006 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Oxford, UK | Included in publication |

| Weymiller 2007 | Diabetes mellitus type 2 treatment | Yes | Montori, Rochester MN, USA | mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/ker_unit/form.cfm |

| Williams 2013 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA | Obtained from author taylorkl@georgetown.edu |

| Whelan 2003 | Breast cancer chemotherapy | Yes | Whelan, Hamilton CA, 1995 | Included in publication |

| Whelan 2004 | Breast cancer surgery | Yes | Whelan, Hamilton CA, 1997 | Included in publication |

| Wolf 1996 | Prostate cancer screening | Yes | Wolf, Charlottesville VA, USA, 1996 | Script in publication |

| Wolf 2000 | Colon cancer screening | Yes | Wolf, Charlottesville VA, USA, 2000 | Script in publication |

| Wong 2006 | Pregnancy termination | No | Bekker, Leeds, UK, 2002 | — |

The decision aids used different formats and were compared to a variety of control interventions (e.g. usual care, general information, no intervention, guideline, placebo intervention). We noted the nature of usual care when reported (see Characteristics of included studies table). For this review, we have grouped control interventions and refer to them as 'usual care'.

According to the definition of a patient decision aid, all of the studies evaluated patient decision aids that included information about the options and outcomes and provided at least implicit clarification of values. Most patient decision aids included information on the clinical problem (90.5%) as well as outcome probabilities (89.5%). Fewer patient decision aids provided guidance in the steps of decision making (65.7%), explicit methods to clarify values (57.1%), and/or examples of others' experiences (41.0%) (see table Characteristics of included studies).

Excluded studies

We excluded 302 studies upon close perusal of the relevant papers (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The reasons for exclusion were: the study was not a randomized controlled trial; the decision was hypothetical, with participants not actually at a point of decision making; the intervention was not focused on making a choice; the intervention offered no decision support in the form of a decision aid or did not provide enough information about the decision aid; no comparison outcome data were provided; the study did not evaluate the decision aid; the study was a protocol; the decision aid was about clinical trial entry, lifestyle choice, or advanced care planning; the study involved testing the presentation of the decision aid, but with no difference in the content of the decision aid between study groups; or the study compared a detailed versus simple decision aid.

We also identified 61 ongoing RCTs through trial registration databases, personal contact, and published protocols in the electronic database searches (see references to Ongoing studies and table Characteristics of ongoing studies).

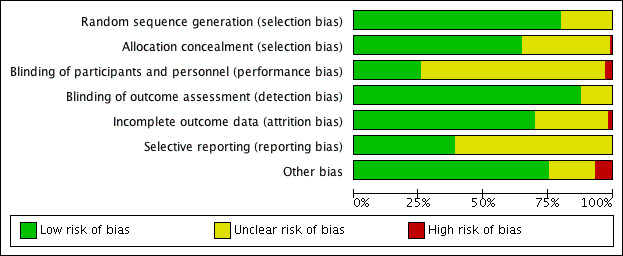

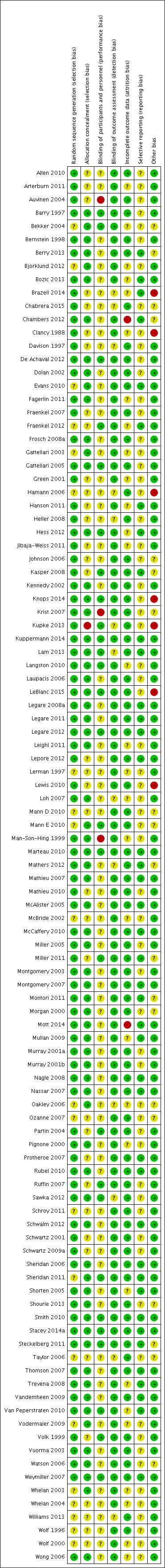

Risk of bias in included studies

Details on the ratings and rationale for risk of bias are in the Characteristics of included studies table and displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary for each included study.

Allocation

When assessing risk of selection bias, we rated all 105 studies as being at low or unclear risk of bias. Allocation concealment methods prompted a rating of low or unclear risk of bias in 104 studies and high risk of bias in 1 study (Kupke 2013).

Blinding

We judged 102 studies to be at low or unclear risk of performance and detection bias for the blinding of participants and personnel, while 3 (2.9%) studies were at high risk of bias. High risk of bias was due to lack of blinding of physicians to the status of patients randomized to the patient decision aid and alternative interventions (Auvinen 2004; Krist 2007; Man‐Son‐Hing 1999).

We rated the blinding of outcome assessment as leading to low or unclear risk of bias in all 105 studies.

Incomplete outcome data

For 103 studies, aspects related to incomplete outcome data conferred low or unclear risk of bias. In two (1.9%) studies (Chambers 2012; Mott 2014), there was high risk of bias due to high attrition rates.

Selective reporting

We rated all 105 studies as being at either low risk of bias because the protocol was registered publicly or at unclear risk of bias because we could not assess the extent or the impact of any reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Of 105 studies, we rated 98 as being at low or unclear risk of other potential sources of bias. The other seven (6.7%) discussed other potential risks of bias (Brazell 2014; Clancy 1988; Hamann 2006; Knops 2014; Kupke 2013; LeBlanc 2015; Lewis 2010). We rated Brazell 2014 and LeBlanc 2015 as being at high risk of bias given that the same physicians provided consultation to both intervention and control groups, and measures were taken after physician consultation. Clancy 1988 describes a potential for selection bias because non‐randomized medical residents were added to the decision aid group, and there was a low response rate among those offered decision aid. We rated Knops 2014 as being at high risk of bias given that a large number of potential participants did not participate in the study. Hamann 2006, Kupke 2013, and Lewis 2010 did not account for clustering in their analyses.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

In addition to Table 1, see the Data and analyses figures for pooled data and Additional tables for outcome data that we did not pool. This section presents the attributes of the choice made, the attributes of the decision process, and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Attributes of the choice made: does the patient decision aid improve the match between the chosen option and the features that matter most to the informed patient?

The randomized controlled trials used three measures that correspond to this outcome: knowledge scores, accuracy of risk perceptions, and congruence between the chosen option and the patient's values.

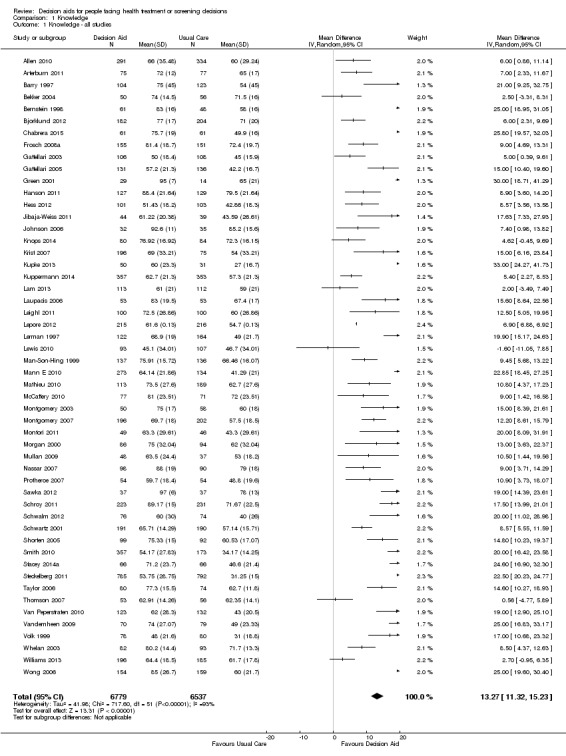

Knowledge

Seventy‐one of the 105 studies (67.6%) assessed the effects of decision aids on knowledge. The studies' knowledge tests were based on information contained in the decision aid. The proportion of accurate responses was transformed to a percentage scale ranging from 0% (no correct responses) to 100% (fully correct responses).

There is high‐quality evidence that patient decision aids were more effective than usual care (52 studies) on knowledge scores (MD 13.27, 95% CI 11.32 to 15.23; Analysis 1.1). In absolute terms the group receiving usual care had, on average, 57 of 100 answers correct. Those in the decision aid group scored better, with 70 of 100 answers correct on average (from 68 to 72 correct).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Knowledge, Outcome 1 Knowledge ‐ all studies.

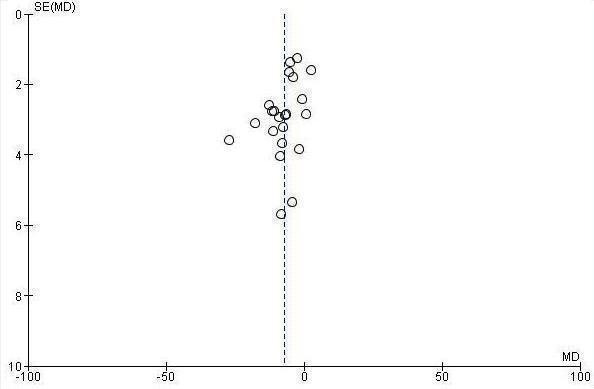

Nineteen additional studies presented knowledge scores that could not be included in the pooled outcome (see Table 3). Most of these other studies reported statistically‐significantly higher knowledge scores for those exposed to the decision aid compared to usual care. The funnel plot for knowledge as an outcome in studies comparing decision aid to usual care shows that these studies are at low risk for publication bias (Figure 4).

2. Knowledge.

| Study | Scale used | Timing | N decision aid | Decision aid ‐ mean | N comparison | Comparison ‐ mean | Notes |

| Bozic 2013 | Decision quality instrument, 19 items re knowledge (> 50%) | After 1st consultation with surgeon | 60 | 58.3% | 60 | 33.3% | P = 0.01 |

| Evans 2010 | 12 true or false questions; scores ranging from −12 to 12 | Immediately post | 89 | 4.9 | 103 | 2.17 | P < 0.001 |

| Fagerlin 2011 | Insufficient (≤ 50% correct) | Immediately post | 383 | 31.8% | 102 | 93.1% | P < 0.001 |

| Sufficient | Immediately post | 383 | 61.9% | 102 | 6.9% | — | |

| Fraenkel 2012 | Open‐ended questions about medication options to reduce stroke ‐ knows medications | Postintervention | 66 | 61% | 62 | 31% | OR 3.5 (95% CI: 1.6 to 7.7, P = 0.001) |

| Open‐ended questions about side effects of medications ‐ knows side effects | Postintervention | 53 | 49% | 46 | 37% | OR 1.9 (95%CI: 0.9 to 4.0; P = 0.07) | |

| Hamann 2006 | 7‐item multiple choice knowledge test (unable to standardize results) | On discharge (˜ 1 month) | 49 | 15 (4.4 SD) | 58 | 10.9 (5.4 SD) | P = 0.01 |

| Heller 2008 | 12‐item multiple choice | Pre‐operatively | 66 | 14%* | 67 | 8%* | *mean increase from baseline P = 0.02 |

|

LeBlanc 2015 (in consultation) |

13‐item questionnaire (median, IQR) total score | Immediately post | 32 | 7 (4.5 to 9.0) | 45 | 5.5 (2.5 to 8.0) | P = 0.11 |

| 9‐items knowledge based on decision aid | Immediately post | 32 | 6 (3.5 to 6.5) | 45 | 4 (2.0 to 8.0) | P = 0.01 | |

| Legare 2008a | 10‐item yes/no/unsure general knowledge test about natural health products (not specific to outcomes of options) | Change scores from baseline to 2 weeks | 43 | 0.86 ± 1.77 P = 0.002 |

41 | 0.51 ± 1.47 P = 0.031 | No difference between groups (P = 0.162) |

|

Mann D 2010 (in consultation) |

14‐item survey | Immediately post | — | — | — | — | No difference in level of knowledge between groups |

| Mathers 2012 | Correctly answers question about best option to lower blood sugar | 6 months postintervention | 95 | 51.6% | 80 | 28.8% | P < 0.001 |

| Correctly answers question about best option to lower complications | 6 months postintervention | 95 | 31.0% | 80 | 29% | P = 0.90 | |

| Mathieu 2007 | 9‐item ‐ 4 concept questions and 5 numeric questions | — | 351 | — | 357 | — | Significantly higher mean increase for the intervention group (2.62 ) compared to control group (0.68) from baseline, P < 0.001 |

| Miller 2005 | 8‐item survey | 2‐week, 2‐month, and 6‐month follow‐ups | — | — | — | — | Intervention type had no impact on general or specific knowledge |

| Nagle 2008 | Good level knowledge was scored higher than the mid point of the knowledge scale (greater than 4) | — | — | — | — | — | 88% (147/167) in DA group compared to 72% (123/171) pamphlet group. OR 3.43 (95% CI 1.79 to 6.58) |

| Ozanne 2007 (in consultation) | Change in knowledge from baseline | Post‐test | 15 | 48% to 64% | 15 | 45% to 57% | change in knowledge score was significant for decision aid (P = 0.01) but not control (P = 0.13) |

| Partin 2004 | 10‐item knowledge index score | 2 weeks | 308 | 7.44 | 290 | 6.9 | P = 0.001 |

| Rubel 2010 | 24‐items adapted from existing prostate cancer knowledge measures | Immediately post | 100 | — | 100 | — | The total mean standardized knowledge score was 84.38 (SD 12.38) |

| Trevena 2008 | Adequate knowledge (positive score: understanding benefits/harms) | 1 month | 134 | 28/134 | 137 | 8/137 | P = 0.0001 |

| Watson 2006 | 12‐item true/false/don't know | Post‐test | 468 | 75% (range 0 to 100) | 522 | 25% (range 0 to 100) | P < 0.0001 |

| Weymiller 2007 (in consultation) | 14‐item ‐ 9 addressed by decision aid; 5 were not | Immediately post | 52 | 46 | — | Mean difference between groups 2.4 (95% CI 1.5 to 3.3) P < 0.05 (when decision aid administered during the consultation only ‐ not if prior to the consultation) |

CI: confidence interval; DA: decision aid; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Knowledge, outcome: 1.1 Knowledge ‐ all studies.

Accurate risk perceptions (i.e. perceived probabilities of outcomes)

Of 105 studies, 25 (23.8%) examined the effects of patient decision aids on the accuracy of patients' perceived probabilities of outcomes (see Analysis 2.1; Table 4). We classified the accuracy of perceived outcome probabilities according to the percentage of individuals whose judgments corresponded to the scientific evidence about the chances of an outcome for similar people. For studies that elicited risk perceptions using multiple items, we averaged the proportion of accurate risk perceptions.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Accurate risk perceptions, Outcome 1 Accurate risk perceptions ‐ all studies.

3. Accurate risk perceptions.

| Study | Scale used | Timing | N decision aid | Decision aid ‐ mean | N comparison | Comparison ‐ mean | Notes |

| Fraenkel 2012 | Accuracy of stroke risk (reported by taking the absolute value of the difference between the participant's risk as estimated by the DA and the estimate provided by the participant ‐ out of 100; lower score indicates more accurate estimation of risk) |

Postintervention | 69 | 9.1 (SD 13.3) | 66 | 14.2 (SD 13) | P = 0.002 |

| Accuracy of bleeding risk (reported same as above) |

Postintervention | 69 | 8.7 (SD 12.5) | 66 | 13.1 (SD 12.2) | P = 0.004 | |

| Hanson 2011 | Expectation of benefit index 11 items score from 1 to 4 with lower score indicating better knowledge | Post (after reviewing DA) | 127 | 2.3 | 129 | 2.6 | P = 0.001 |

| Kuppermann 2014 | Correct estimate of amniocentesis miscarriage risk | 3‐6 months postintervention | 357 | 263 (73.8%) | 353 | 208 (59.0%) | P < 0.001 |

| Correct estimate of Down syndrome risk | 3‐6 months postintervention | 357 | 210 (58.7%) | 353 | 163 (46.1%) | P = 0.001 | |

| Mann E 2010 | 3 of 8 multiple choice items in the knowledge test (question 4, 5, 7) | 2 weeks post | — | — | — | — | Total knowledge reported only |

| Mathieu 2010 | 5 item numerical questions (max = 5) | Post | 113 | 3.02 | 189 | 2.45 | P < 0.001 |

| Miller 2005 | — | 2‐week, 2‐month, and 6‐month follow‐ups | — | — | — | — | Intervention type had no impact on risk perceptions |

| Smith 2010 | 8 numerical questions (max = 8) | — | 357 | 2.93 (SD 2.91) | 173 | 0.58 (SD 1.28) | P < 0.001 |

| Weymiller 2007 (in consultation) | — | Immediately | 52 | — | 46 | — | Difference between group OR 22.4 (95% CI 5.9 to 85.8) when decision aid administered during the consultation only (not if prior to) OR 6.7 (95% CI 2.2 to 19.7) when the decision aid administered prior to or during the consultation |

CI: confidence interval; DA: decision aid; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation.

There is moderate‐quality evidence that patient decision aids were more effective than usual care for transmitting accurate risk perceptions (risk ratio (RR) 2.10, 95% CI 1.66 to 2.66, 17 studies; Analysis 2.1). This means that for every 1000 people receiving usual care, 269 were likely to accurately interpret risk, whereas far more people (565 people per 1000; from 447 to 716) accurately interpreted risk after using a decision aid.

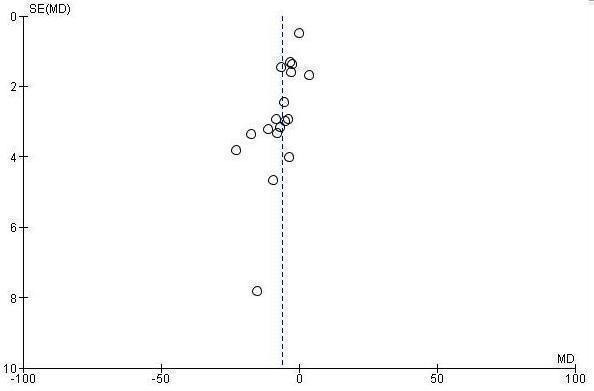

Eight studies reported results that were not amenable to pooling (see Table 4). Fraenkel 2012; Hanson 2011; Kuppermann 2014; Mathieu 2010; and Smith 2010 reported a statistically significant improvement in accurate perceptions of outcomes for the decision aid group compared to usual care, and Miller 2005 reported no effect on risk perception. In another study, Weymiller 2007 reported participants allocated to the decision aid had a significantly more accurate perception of their estimated cardiovascular risk without statin therapy compared to the usual care group; this effect was greater when the clinician used the decision aid during the consultation rather than when the researcher used the decision aid in preparation for the consultation (Pinteraction= 0.03). For the final study by Mann E 2010, three of eight knowledge test items measured accurate risk perceptions, but results were presented for total knowledge and not individual items.The funnel plot for accurate risk perception as an outcome in studies comparing decision aid to usual care shows low risk for publication bias.

Congruence between chosen option and values

Of 105 studies, 16 (15.3%) measured congruence between the chosen options and the patients' values. Six measured values‐choice congruence without considering knowledge (Arterburn 2011; Berry 2013; Frosch 2008a; Legare 2008a; Lerman 1997; Vandemheen 2009). Of 10 studies that measured informed values‐choice congruence, eight used the Multi‐Dimensional Measure of Informed Choice (Bjorklund 2012; Fagerlin 2011; Mathieu 2007; Mathieu 2010; Nagle 2008; Smith 2010; Steckelberg 2011; Trevena 2008), which assesses the extent to which the choice is based on relevant knowledge, is consistent with a person's values/attitudes, and is behaviourally implemented (Michie 2002). These studies operationalized the measure in terms of knowledge scores higher than the mid‐point of the scale, attitude scale scores higher than the mid‐point, and choice being congruent with attitude.Two other studies measured informed values‐based choice: Schwalm 2012 assessed the extent to which the choice was based on knowledge score ≥ 60% and a score for three values‐importance ratings that matched the choice; and Stacey 2014a assessed the extent to which the choice was based on knowledge score ≥ 66% and measured values‐choice congruence using a logistic regression model. For the 10 studies that measured informed values‐choice congruence, two used preferred choice (Mathieu 2010; Trevena 2008), and the other eight used actual choice.

There is low quality evidence that patient decision aids were more effective than usual care for selecting an option that was congruent with their informed values (RR 2.06, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.91, 10 studies; Analysis 3.1). Of the 10 studies, 8 individually showed statistically higher congruence scores for the patient decision aid compared to usual care, and 2 showed no difference (Bjorklund 2012; Mathieu 2010). Repeating this analysis using the studies that measured actual choice and not preferred choice revealed a pooled RR of 2.13 (95% CI 1.44 to 3.14; 8 studies). A sub‐analysis of studies using the Multi‐Dimensional Measure of Informed Choice revealed a pooled RR of 2.08 (95% CI 1.40 to 3.08, 8 studies; Analysis 3.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Informed values‐choice congruence, Outcome 1 Informed values‐choice congruence ‐ all studies.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Informed values‐choice congruence, Outcome 3 Informed values‐chose congruence ‐using MMIC.

There was no difference between patient decision aid and usual care for the six studies that measured values‐choice congruence without considering knowledge scores (Arterburn 2011; Berry 2013; Frosch 2008a; Legare 2008a; Lerman 1997; Vandemheen 2009; see Table 5). We did not pool these studies because of how they reported results. Arterburn 2011 reported that, compared to the control group, those exposed to the decision aid experienced a more rapid early improvement of value‐choice concordance immediately after exposure. Legare 2008a reported that women's valuing of the non‐chemical aspect of natural health products was positively associated with their choice of natural health products in managing menopausal symptoms (P = 0.006). The other four studies reported no differences between groups. However, Frosch 2008a observed that men exposed to the decision aid who chose not to have a prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) test rated their concern about prostate cancer lower than men who requested a PSA test, while men assigned to the usual care group provided similar ratings of concern regardless of their PSA choice.

4. Values congruent with chosen option.

| Study | Scale used | Timing | N decision aid | Decision aid ‐ mean | N comparison | Comparison ‐ mean | Notes |

| Arterburn 2011 | Percent match procedures described by Sepucha et al (2007; 2008). For values items were most predictive and used to specify logistic models to estimate predicted probability of selecting surgery > 0.5. | Postintervention | 75 | — | 77 | — | The intervention group experienced a more rapid early improvement in value concordance immediately after the intervention compared to control |

| Berry 2013 | Concordant when men reported:a) sexual function influenced decision and they had radiation therapy; b) bowel function influenced decision and they had surgery; c) all effects influenced decision and they had surveillance | 6 months postintervention | 239 | — | 209 | — | No difference OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.56 to 1.2 |

| Frosch 2008a | Concordance between participant's preferences and values for potential outcomes related to the decision and the choice made | within weeks | 155 | — | 151 | — | Men assigned to the decision aid who chose not to have a PSA test rated their concern about prostate cancer lower than did men who requested a PSA test. Men assigned to usual care provided similar ratings of concern about prostate cancer regardless of their PSA decision. There was no statistically significant difference between groups. |

| Legare 2008a | — | — | — | — | — | — | Women valuing of non‐chemical aspect of natural health products was positively associated with their choice of nature health products, P = 0.006. No difference between groups |

| Lerman 1997 | Association between values and choice | — | — | — | — | — | No difference; between‐group differences were not reported |

| Vandemheen 2009 | Congruence between personal values and decision | 3 weeks | 70 | — | 70 | — | Patient choices were consistent with their values across both randomized groups |

DA: decision aid; SD: standard deviation.

Attributes of the decision process: does the decision aid help patients to recognize that a decision needs to be made, know the options and their features, understand that values affect the decision, be clear about the features that matter most to them, discuss values with their clinician, and become involved in their preferred ways?

In relation to the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) decision process criteria, no studies evaluated the extent to which patient decision aids helped participants to recognize that a decision needed to be made or understand that values affect the decision. Some studies measured participants' self‐reports about feeling informed and clear about personal values. The measures used to evaluate these criteria were two subscales of the previously validated Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) (O'Connor 1995).

Decisional conflict

Of 105 studies, 63 (60.0%) evaluated decisional conflict using the DCS (O'Connor 1995). The DCS is reliable, discriminates between those who make or delay decisions, is sensitive to change, and discriminates between different decision support interventions (Morgan 2000; O'Connor 1995; O'Connor 1998b). The scale measures the constructs of overall decisional conflict and the particular factors contributing to uncertainty (e.g. feeling uncertain, uninformed, unclear about values, and unsupported in decision making). A final subscale measures perceived effective decision making. The scores were standardized to range from 0 (no decisional conflict) to 100 points (extreme decisional conflict). Scores of 25 or lower are associated with follow‐through with decisions, whereas scores that exceed 38 are associated with delay in decision making (O'Connor 1998b). When decision aids are compared to usual care, a negative score indicates a reduction in decisional conflict, favouring the decision aid.

Analysis 4.1.1 summarizes the decisional conflict results for the 42 studies that compared decision aids to usual care. We report on 21 studies that were not amenable to pooling in Table 6 (original DCS), Table 7 (low literacy version), and Table 8 (SURE test version).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Decisional conflict, Outcome 1 Decisional conflict ‐ all studies.

5. Decisional Conflict Score.

| Study | Scale used | Timing | N decision aid | Decision aid ‐ mean | N comparison | Comparison ‐ mean | Notes |

| Arterburn 2011 | Total decisional conflict‐ change from baseline (standardised values) | Immediately post | 75 | Mean −20 SD 19.44 | 77 | Mean −11.8 SD 22.83 | P = 0.03 |

| Berry 2013 | Decisional conflict scale | Uncertainty | — | −3.61 units | — | — | P = 0.04 |

| Uninformed | — | — | — | — | No significant difference | ||

| Unclear values | — | −3.57 units | — | — | P = 0.002 | ||

| Unsupported | — | — | — | — | No significant difference | ||

| Ineffective decision | — | — | — | — | No significant difference | ||

| Total | — | −1.75 units | — | — | P = 0.07 | ||

| Fagerlin 2011 | Decisional conflict scale | Immediately post | — | — | — | — | DCS was higher in the intervention group compared to control, P < 0.001. |

| Frosch 2008a | Decisional conflict ‐ subscales only | Feeling uninformed | 155 | 23.37 | 151 | 29.68 | P < 0.05 |

| Feeling unclear values | 155 | 32.25 | 151 | 37.93 | P < 0.05 | ||

| Feeling supported | 155 | 30.51 | 151 | 35.21 | P < 0.05 | ||

| Feeling uncertain | 155 | — | 151 | — | No difference | ||

| Effective decisions | 155 | — | 151 | — | No difference | ||

| Knops 2014 | Decisional conflict (total score) | 4 months | 73 | 19 SD 14 | 81 | 22 SD 17 | No difference |

| 10 months | 73 | 21 SD 17 | 81 | 18 SD 17 | No difference | ||

| Krist 2007 | Decisional conflict | Immediately after office visit | 196 | 1.54 | 75 | 1.58 | No difference |

| LeBlanc 2015 (in consult) | Decision conflict (overall) median, IQR | Immediately post | 28 | 10.9 (95% CI 1.6 to 26.6) | 36 | 22.7 (95% CI 7.8 to 28.5) | P = 0.18 |

| Informed subscale | Immediately post | 28 | 4.2 (95% CI 0 to 25) | 36 | 20.8 (95% CI 0 to 33.3) | P = 0.14 | |