Abstract

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common inherited diseases worldwide. It is associated with lifelong morbidity and a reduced life expectancy. Hydroxyurea (hydroxycarbamide), an oral chemotherapeutic drug, ameliorates some of the clinical problems of SCD, in particular that of pain, by raising fetal haemoglobin. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of hydroxyurea therapy in people with SCD (all genotypes), of any age, regardless of setting.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group Haemoglobinopathies Register, comprising of references identified from comprehensive electronic database searches and handsearches of relevant journals and abstract books of conference proceedings. We also searched online trial registries.

Date of the most recent search: 16 January 2017.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials, of one month or longer, comparing hydroxyurea with placebo, standard therapy or other interventions for people with SCD.

Data collection and analysis

Authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, carried out data extraction and assessed the risk of bias.

Main results

Seventeen studies were identified in the searches; eight randomised controlled trials were included, recruiting 899 adults and children with SCD (haemoglobin SS (HbSS), haemoglobin SC (HbSC) or haemoglobin Sβºthalassaemia (HbSβºthal) genotypes). Studies lasted from six to 30 months.

Four studies (577 adults and children with HbSS or HbSβºthal) compared hydroxyurea to placebo; three recruited individuals with only severe disease and one recruited individuals with all disease severities. There were statistically significant improvements in terms of pain alteration (using measures such as pain crisis frequency, duration, intensity, hospital admissions and opoid use), measures of fetal haemoglobin and neutrophil counts and fewer occurrences of acute chest syndrome and blood transfusions in the hydroxyurea groups. There were no consistent statistically significant differences in terms of quality of life and adverse events (including serious or life‐threatening events). Seven deaths occurred during the studies, but the rates by treatment group were not statistically significantly different.

Two studies (254 children with HbSS or HbSβºthal also with risk of primary or secondary stroke) compared hydroxyurea and phlebotomy to transfusion and chelation; there were statistically significant improvements in terms of measures of fetal haemoglobin and neutrophil counts, but more occurrences of acute chest syndrome and infections in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group. There were no consistent statistically significant differences in terms of pain alteration and adverse events (including serious or life‐threatening events). Two deaths occurred during the studies (one in a the hydroxyurea treatment arm and one in the control arm), but the rates by treatment group were not statistically significantly different. In the primary prevention study, no strokes occurred in either treatment group but in the secondary prevention study, seven strokes occurred in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group (none in the transfusion and chelation group) and the study was terminated early.

The quality of the evidence for the above two comparisons was judged as moderate to low as the studies contributing to these comparisons were mostly large and well designed (and at low risk of bias); however evidence was limited and imprecise for some outcomes such as quality of life, deaths during the studies and adverse events and results are applicable only to individuals with HbSS and HbSβºthal genotypes.

Of the remaining two studies, one (22 children with HbSS or HbSβºthal also at risk of stoke) compared hydroxyurea to observation; there were statistically significant improvements in terms of measures of fetal haemoglobin and neutrophil counts but no statistically significant differences in terms of adverse events (including serious or life‐threatening events).

The final study (44 adults and children with HbSC) compared treatment regimens with and without hydroxyurea – there was statistically significant improvement in terms of measures of fetal haemoglobin, but no statistically significant differences in terms of adverse events (including serious or life‐threatening events). No participants died in either of these studies and other outcomes relevant to the review were not reported.

The quality of the evidence for the above two comparisons was judged to be very low due to the limited number of participants, the lack of statistical power (as both studies were terminated early with approximately only 20% of their target sample size recruited) and the lack of applicability to all age groups and genotypes.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence to suggest that hydroxyurea is effective in decreasing the frequency of pain episodes and other acute complications in adults and children with sickle cell anaemia of HbSS or HbSβºthal genotypes and in preventing life‐threatening neurological events in those with sickle cell anaemia at risk of primary stroke by maintaining transcranial doppler velocities. However, there is still insufficient evidence on the long‐term benefits of hydroxyurea, particularly in preventing chronic complications of SCD, recommending a standard dose or dose escalation to maximum tolerated dose. There is also insufficient evidence about the long‐term risks of hydroxyurea, including its effects on fertility and reproduction. Evidence is also limited on the effects of hydroxyurea on individuals with HbSC genotype. Future studies should be designed to address such uncertainties.

Plain language summary

Hydroxyurea (also known as hydroxycarbamide) for people with sickle cell disease

Review question

What is the effect of hydroxyurea on clinical outcomes (changes in pain crises, life‐threatening illnesses, survival, haemoglobin levels, quality of life and side effects) in people with sickle cell disease (SCD) of any genotype?

Background

SCD is an inherited genetic disorder that creates problems with haemoglobin (the substance in red blood cells that carries oxygen around the body). The disease can be inherited in different ways; people can inherit two sickle genes (HbSS genotype) or they can inherit the sickle gene from one parent and a different haemoglobin gene (such as haemoglobin C (HbSC genotype) or a beta thalassaemia gene (HbSβ+ or HbSβºthal genotype)) from the second parent.

In people with SCD the abnormal sickle haemoglobin forms long polymers (chains) within the red blood cells when they become de‐oxygenated. This damages the red blood cells and makes them stickier, leading to blockages and reduced blood flow, causing pain and organ damage. Fetal haemoglobin stops these polymers forming in the sickle haemoglobin within the red blood cell. The drug hydroxyurea is used to raise fetal haemoglobin and can reduce the effects of the disease. This is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review.

Search date

The evidence is current to 16 January 2017.

Study characteristics

We included eight studies (899 adults and children with SCD (HbSS, HbSC or HbSβºthal genotypes)). Studies lasted from six to 30 months.

Key results and quality of the evidence

In four studies, 577 adults and children with SCD were randomly selected to receive hydroxyurea or placebo. In two studies, 254 children with SCD, who were also at an increased risk of having a first or second stroke, were randomly selected to receive hydroxyurea and phlebotomy (collection of blood) or blood transfusion and chelation (administration of agents to remove excess iron from the body). These six studies only recruited people with HbSS or HbSβºthal genotypes so results do not apply to people with the HbSC genotype.

There was moderate quality evidence from these six studies that those receiving hydroxyurea experienced significant reductions in the frequency of pain crises, increases in fetal haemoglobin and decreases in neutrophil (white blood cell) counts compared to the comparator treatment. There was no difference between people receiving hydroxyurea or other treatments in terms of quality of life, deaths during the studies and side effects (including serious and life‐threatening side effects); however, there is less information about these outcomes in the studies, so the quality of this evidence is low.

Two further studies were included in the review. In one study, 22 children with SCD, who were also at an increased risk of having a stroke, were randomly selected to receive hydroxyurea or no treatment (observation only) and in one study 44 adults and children were randomly selected to receive treatments with or without adding hydroxyurea. Both studies showed an increase in fetal haemoglobin for people receiving hydroxyurea compared to the comparator treatment and there were no deaths during the studies. There was no difference between people receiving hydroxyurea or other treatments in terms of pain crises and side effects (including serious or life‐threatening side effects) and these studies did not measure quality of life. The quality of the evidence from these studies is very low, given the studies were very small and only recruited around 20% of the intended number of people and results do not apply to all people with SCD (different genotypes).

Conclusions

The evidence shows that hydroxyurea is likely to be effective in the short term at decreasing the frequency of painful episodes and raising fetal haemoglobin levels in the blood in people with SCD. Hydroxyurea is also likely to be effective in preventing first strokes for those at an increased risk of stroke and does not seem to be associated with an increase in any side effects (including serious and life‐threatening side effects).

There is currently not much evidence on whether hydroxyurea is beneficial over a long period of time, what the best dose to take is, or whether treatment causes any long‐term or serious side effects. More studies are needed to answer these questions.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Haemoglobinopathies, including sickle cell disease (SCD), are among the most common inherited disorders in the world. SCD affects people originating from sub‐Saharan Africa, Arab countries, the Mediterranean, the Indian subcontinent, the Caribbean and South America, as well as African‐Americans and descendants from immigrants from the above countries in other parts of the world. The genetic mutation gives carriers some advantage against malaria and for this reason has persisted. There is an estimated global birth rate of around 300,000 affected individuals per year, the majority of which are in Africa (Piel 2013). There are an estimated 90,000 to 100,000 individuals with SCD in the USA and approximately 12,000 to 15,000 in the UK (Brousseau 2010; Hassell 2010; NICE 2012).

Haemoglobin is responsible for transporting oxygen around the body packaged in red blood cells. SCD is caused by the recessive inheritance of abnormal haemoglobins. People who inherit only one sickle gene and the normal gene for adult haemoglobin (HbA) are sickle cell carriers (sickle cell trait or AS) and are healthy. When people are homozygous, because they have inherited two sickle genes (SS), they have sickle cell anaemia, which is a variable clinical condition, with the vast majority of individuals suffering some pain attacks and a reduced life expectancy. Clinically significant SCD also arises when people inherit the sickle gene from one parent and another variant haemoglobin gene from the second parent such as haemoglobin C (SC) or a beta thalassaemia gene (Sβ+ or Sβ0). Sickle haemoglobin, when not carrying oxygen, polymerises distorting the red blood cell into the classic 'sickle' shape. The clinical problems arise predominantly as a result of chronic anaemia and the blockage of small blood vessels, which stops oxygen delivery to the tissues causing pain or organ damage or both.

The most frequent clinical problem is pain which causes over 90% of acute hospital admissions (Brozovic 1987) and significant morbidity in the community (Fuggle 1996). Other acute complications include acute chest syndrome, stroke, splenic sequestration, priapism and an increased risk of infection. SCD is a multi‐organ disease with a high chronic disease burden which increases with increasing age. The majority of individuals are anaemic with haemoglobin levels of 60 to 90g/L in HbSS. Common chronic complications include chronic sickle lung damage, pulmonary hypertension, renal dysfunction, chronic bony damage (avascular necrosis), retinopathy and leg ulceration (Howard 2015).

Whilst the majority of those affected used to die in childhood, and still do within parts of the developing world (Chakravorty 2015; Grosse 2011), death rates in children in higher‐income countries have fallen over the past decades and the majority of children (over 95%) now survive to adulthood (Quinn 2010; Telfer 2007; van der Plas 2011). Data from the USA reviewing national mortality data from 1979 to 2005 has confirmed this decrease in mortality in children, but showed an increased mortality rate in adults with a median age of death of 42 years for women and 38 years for men (Lanzkron 2013). Earlier data from the USA showed a median survival for adults with HbSS in the USA of 42 years in men and 46 years in women and in HbSC of 60 years and 68 years, respectively (Platt 1994). This contrasts with Jamaican figures which show median survival for HbSS of 53 years for men and 58.5 years for women (Wierenga 2001) and recent single‐centre data from the UK has shown median survival of 67 years in people with HbSS and higher in those with HbSC (Gardner 2016). Data from the USA has also shown an increase in deaths following transition from paediatric to adult services (Quinn 2010). Death is generally SCD‐related and is caused either by chronic organ failure consequent to the sickling process (e.g. renal failure, pulmonary hypertension, hepatic failure) (Manci 2003) or as a result of an acute catastrophic event, such as stroke (Powars 1983), acute sickle chest syndrome, splenic sequestration (Rogers 1978), sepsis (Manci 2003; van der Plas 2011) or other complications (Gray 1991; Lanzkron 2013; Perronne 2002). The UK National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) report reviewed UK mortality data over 48 months and found six paediatric and 40 adult deaths. One paediatric death was due to pneumococcal sepsis and two were due to sub‐arachnoid haemorrhage. In adults the main causes of death were stroke, multi‐organ failure, acute chest syndrome, renal failure and non‐sickle causes (NCEPOD 2008).

Improvements in paediatric outcomes are related to the introduction of neonatal screening, early enrolment in comprehensive paediatric care, penicillin prophylaxis, vaccination to decrease life‐threatening infection and primary stroke prevention with transcranial Doppler screening. In adults, treatment has relied on the avoidance of factors that precipitate crisis (including dehydration, infection and cold), and symptomatic treatment of the acute painful episodes (Davies 1997a; Davies 1997b; Steinberg 1999; STOP 2006). Hydroxyurea is currently the only licensed treatment for SCD. Blood transfusion is often required and may be used to treat acute complications or in the long term to treat or prevent disease complications. Haemopoeitic stem cell transplantation is the only currently available curative treatment option and is offered to children with severe disease phenotype and an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐matched sibling donor. Other donor transplant options and adult transplant are currently only available in the context of clinical trials. Gene therapy offers another potential curative treatment and is currently being investigated in clinical trials.

Description of the intervention

Hydroxyurea (also known as hydroxycarbamide) is an anti‐neoplastic oral drug and an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (BABY HUG 2011). The drug has been shown to have many beneficial effects for treating SCD; including increasing fetal haemoglobin (HbF) concentration in red blood cells, improving nitric oxide metabolism, reducing red cell‐endothelial interaction and erythrocyte density (Ware 2010). Such disease‐modifying effects have been shown to decrease episodes of pain, acute chest syndrome, hospital admissions and the need for transfusions among people with SCD (MSH 1995; Strouse 2008); however, frequent monitoring of the person's blood count is required, in addition to monitoring of toxicity. There are recognised, but mostly reversible, side effects of hydroxyurea, such as low neutrophil count, low platelet count, anaemia, rash, headache and occasionally nausea. Furthermore, it may have teratogenic effects and may have an effect on male fertility (Strouse 2008;Zimmerman 2004). Long‐term or serious adverse effects (or both) of hydroxyurea are rare (Steinberg 2010; Strouse 2008) and observational data suggest a survival advantage for those treated with hydroxyurea (Steinberg 2010; Voskaridou 2010).

How the intervention might work

It has long been recognised that raised HbF levels can ameliorate the clinical effects of SCD (Perrine 1978; Platt 1994). HbF levels are high at birth and decrease over the first year of life and and hence clinical manifestations are often delayed until the HbF levels decrease. In addition, individuals who inherit high levels of HbF display a milder disease phenotype. This is because the HbF interferes with the polymer formation of the sickle haemoglobin within the red blood cell. This polymerisation is the underlying pathology in SCD. The more HbF there is, the greater the inhibition. Hydroxyurea was first shown to raise HbF levels in SCD in the 1980s (Platt 1984; Veith 1985). Its intermittent toxicity on the bone marrow leads to a stress response and enhanced erythropoiesis and levels of HbF. In addition to its effects on SCD via HbF enhancement, hydroxyurea also improves blood flow and reduces vaso‐occlusion via other mechanisms including decrease of adhesion molecules and stimulation of nitric oxide production (Green 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to examine as a whole, the body of work relating to the use of hydroxyurea in SCD, to evaluate the drug's effectiveness and tolerability in adults and children, and in the different types of SCD, the dosage regimens and whether the setting appears to influence the outcome, i.e. high‐income versus low‐ and middle‐income countries. We aim to review any evidence relating to the impact of hydroxyurea on the natural history of SCD and life expectancy.

Objectives

The aims of this review are to determine whether the use of hydroxyurea in people with SCD:

alters the pattern of acute events, including pain;

prevents, delays or reverses organ dysfunction;

alters mortality and quality of life;

is associated with adverse effects.

In addition we hoped to assess whether the response to hydroxyurea in SCD varies with type of SCD, age of the individual, duration and dose of treatment and healthcare setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised studies, irrespective of language. Studies with quasi‐randomised methods, such as alternation, were included if there was sufficient evidence that the treatment and control groups were similar at baseline.

Types of participants

This review is limited to studies of hydroxyurea in SCD only. In order to fully quantify the potential harm and toxicity of this drug, a further review may need to be undertaken in all patient groups treated with hydroxyurea.

People of any age with SCD (SS, Sβ₀, SC, Sβ+) proven by electrophoresis and sickle solubility test, with family studies or DNA tests as appropriate.

Types of interventions

Hydroxyurea in any formulation at all doses, compared to either placebo or standard treatment (no placebo) for periods of one month or longer.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Pain alteration

frequency, duration, severity measured on self‐reported patient scales

health service utilisation (e.g. inpatient days, outpatient or accident and emergency department visits)

opioid use

Life‐threatening illness (e.g. acute chest syndrome, stroke and acute splenic sequestration)*

Death during the study

* In the 2017 update of the review, serious adverse events reported in included studies (whether treatment‐related or not) were included under the definition of 'Life‐threatening illness'.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of fetal haemoglobin (HbF or F cells) and neutrophil counts

Other surrogate markers of response (e.g. haemoglobin, mean cell volume, platelet count and growth)

Quality of life, time loss to school or employment, integration into society, scales recording feeling of well‐being and global function (e.g. Karnofsky)

Measures of organ damage (e.g. spleen (pitted red cells), chronic sickle lung disease (transfer factor), liver, chronic renal failure (creatinine), priapism, leg ulcer, neurological damage (e.g. intelligence quotient (IQ)))

Any reported adverse effects or toxicity

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all relevant published and unpublished trials without restrictions on language, year or publication status.

Electronic searches

Relevant studies were identified from the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register using the terms: sickle cell AND hydroxyurea.

The Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Clinical Trials) (updated each new issue of the Cochrane Library) and weekly searches of MEDLINE. Unpublished work is identified by searching the abstract books of five major conferences: the European Haematology Association conference; the American Society of Hematology conference; the British Society for Haematology Annual Scientific Meeting; the Caribbean Public Health Agency Annual Scientific Meeting (formerly the Caribbean Health Research Council Meeting); and the National Sickle Cell Disease Program Annual Meeting. For full details of all searching activities for the register, please see the relevant section of the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group's website.

Date of the most recent search of the Group's Haemoglobinopathies Trials Register: 16 January 2017.

We also searched the following trials registries on 20 March 2017.

ClinicalTrials.gov using the following search terms: hydroxyurea AND sickle.

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) using the following search terms: hydroxyurea AND sickle.

Searching other resources

The bibliographic references of all retrieved studies and reviews were assessed for additional reports of studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the initial review, two authors (SCD and AO) independently applied inclusion criteria. For the updates to this review, two authors (AJ and SJN) performed this task. There were no discrepancies between the authors' assessments.

Data extraction and management

For the initial review, two authors (SCD and AO) independently extracted the data. For the updates of the review, two authors (AJ and SJN) performed this task. There were no discrepancies between the authors' assessments.

We intended to group outcome data into those measured at three, six, twelve months and annually thereafter. When outcome data were recorded at other time periods, then consideration was given to examining these as well.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the initial review, two authors (SCD and AO) independently assessed the methodological quality of each trial using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins 2011). For the updates of the review, two authors (AJ and SJN) performed these tasks. The authors assessed methodological quality on the methods of concealment and generation of randomisation sequence, blinding, whether data were available to analyse on intention‐to‐treat basis and whether all randomised participants were included in the analysis. There were no discrepancies between the authors' assessments.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes, we aimed to calculate a pooled estimate of the treatment effect for each outcome across studies, (the risk of an outcome among treatment allocated participants to the corresponding risk among controls). For each study, we calculated risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all important, dichotomous outcomes. We present RR in preference to odds ratios (OR), as OR give an inflated impression of the size of effect where event rates are high, as is the case of these studies. For the continuous outcomes, we aimed to calculate a pooled estimate of treatment effect, using the mean difference (MD).

Unit of analysis issues

One study was cross‐over in design (Belgian Study 1996). We planned to analyse data from this study using the approach recommended by Elbourne (Elbourne 2002); extracting and analysing data from paired analyses if possible.

Outcomes were measured at different time points throughout the course of the MSH study. Methods to analyse aggregate longitudinal data if individual patient data are not available are discussed by Jones (Jones 2009); however, data presented did not allow the use of these methods therefore we have carried out analysis at each individual time point reported.

Dealing with missing data

In order to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis, we collected data by allocated treatment groups, irrespective of compliance, later exclusion (regardless of cause) or loss to follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by reviewing the differences across trials in the characteristics of recruited participants and treatment protocols. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using a Chi² test for heterogeneity. We assessed heterogeneity using the Q test (P < 0.10 for significance) and the I² statistic (greater than 50% indicating considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2003)) and visually by inspecting forest plots.

Data synthesis

We analysed data using the fixed‐effect model, if we had found considerable heterogeneity (I² statistic > 50%) then we would have examined it using a random‐effects model and subgroup analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform subgroup analyses according to age (infant, child, adult etc), type of SCD (SS, Sβ₀, SC, Sβ+), dosage regimen (study specific) and setting (community, hospital, outpatient, etc), however, available data did not allow for these analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned a sensitivity analysis based on the methodological quality of the studies, including and excluding quasi‐randomised studies. However, no quasi‐randomised studies were included in the review, therefore, no sensitivity analyses were performed.

Summary of findings and quality of the evidence (GRADE)

In a post hoc change from the protocol, we have presented four summary of findings tables, one for each comparison of the review (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4).

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings ‐ Hydroxyurea compared with placebo for sickle cell disease.

| Hydroxyurea compared with placebo for sickle cell disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with sickle cell disease Settings: outpatients Intervention: hydroxyurea Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Hydroxyurea | |||||

|

Pain alteration1 Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 577 (4 studies)2 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | All studies showed a significant advantage to hydroxyurea compared to placebo (different measures of pain alteration presented)1. |

|

Life‐threatening illness Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 552 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | Significantly fewer occurrences of ACS (2 studies) and transfusions (3 studies) on hydroxyurea compared to placebo. No significant differences in terms of stroke, hepatic or splenic sequestration (two studies). |

|

Death during the study (all deaths) Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

26 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (0 to 51 per 1000) |

RR 0.39 (0.08 to 1.96) | 577 (4 studies)2 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | There was also no significant difference between groups in terms of deaths related to SCD. |

|

Measures of HbF (%) Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 577 (4 studies)2 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | There was a significant increase in HbF(%) in the hydroxyurea group compared to the placebo group in all studies (different measures presented)3. |

|

Measures of ANC Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 517 (3 studies)2 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | There was a significant decrease in ANC in the hydroxyurea group compared to the placebo group in all studies (different measures presented)3. |

|

Quality of life: 'Health Status Survey' the 'Profile of Mood States' and the 'Ladder of Life' Follow‐up: 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | up to 277 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6 |

No significant difference in terms of any domain of any scale except for pain recall at 18 months (MD 0.70, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.29, P = 0.02)4. |

|

Adverse events or toxicity: differences in rates of specific adverse events Follow‐up: 6 ‐ 24 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 577 (4 studies)2 |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,7 |

Significantly fewer events of dactylitis and gastroenteritis on hydroxyurea compared to placebo. No significant differences between groups in terms of all other events. |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the event rate in the control group unless otherwise stated in the comments and footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACS: acute chest syndrome; ANC: absolute neutrophil counts; CI: confidence interval; HbF: fetal haemoglobin; MD: mean difference;NA: not applicable; RR: risk ratio; SCD: sickle cell disease. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

- Pain alteration measured by mean annual pain crisis rate, time to initiation of treatment to first, second or third crisis, number of vaso‐occlusive crises, proportion of participants experiencing pain, proportion of hospitalisation for painful episodes.

- One study of 25 participants is of a cross‐over design (Belgian Study 1996). Participants are counted only once in this total.

- Different measures presented ‐ change from baseline or post intervention measures ‐ therefore, data from all studies could not be pooled.

- Within the study (MSH 1995, reported in Ballas 2006), to allow for multiple statistical testing of the quality of life domains, a P value < 0.01 was considered significant. Therefore this result not interpreted as significant in the study publication.

- Downgraded once due to applicability: only individuals with HbSS or HbSβº‐thalassemia genotypes were included therefore results are not applicable to individuals with HbSC genotype.

- Downgraded once due to imprecision/uncertainty: caution is encouraged regarding the interpretation of these results as not all participants contributed data to all quality of life domains and the study publication defines statistical significance differently to this review.

- Downgraded once due to imprecision/uncertainty: caution is encouraged regarding the interpretation of these results due to the number of separate outcomes considered in analysis and the increased probability of a statistical type I error.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings ‐ Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for people with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke.

| Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for people with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke Settings: outpatients Intervention: hydroxyurea and phlebotomy Comparison: transfusion and chelation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Transfusion and chelation | Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy | |||||

|

Pain alteration: proportion experiencing serious VOC or sickle‐related pain events Follow‐up: 24 to 30 months |

213 per 1000 | 718 per 1000 (339 to 1000 per 1000) |

RR 3.37 (95% CI 1.59 to 7.11) | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 |

No significant difference between treatment groups in terms of all pain events (serious and non‐serious) in 1 study (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.30). |

|

Life‐threatening illness Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 30 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | No significant difference between groups in life‐threatening neurological events, hepatobiliary disease and splenic sequestration; significantly more ACS and infections and infestations in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to the transfusion and chelation group. |

|

Death during the study (all deaths) Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 30 months |

1 death occurred in the transfusion and chelation group of 1 study1. | 1 death occurred in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group of 1 study1. | RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.06 to 15.42) | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 |

|

|

Measures of HbF (%) Follow‐up: 24 to 30 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | There was a significant increase in HbF(%) in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group compared to the transfusion and chelation group for both studies (different measures presented)2. |

|

Measures of ANC Follow‐up: 24 to 30 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | There was a significant decrease in ANC in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group compared to the transfusion and chelation group for both studies (different measures presented)2. |

| Quality of life | Outcome not reported3 | NA | ||||

| Adverse events or toxicity: differences in rates of specific adverse events | See comment | See comment | NA | 254 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,6 |

There was a statistically significant difference in terms of immune disorders (more in transfusion and chelation group), reticulocytopenia, neutropenia and anaemia (more in hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group) in 1 study and the rate of adverse events was balanced across groups in the other study. |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the event rate in the control group unless otherwise stated in the comments and footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACS: acute chest syndrome; ANC: absolute neutrophil counts; CI: confidence interval; HbF: fetal haemoglobin; NA: not applicable; RR: risk ratio; VOC: vaso‐occlusive crisis. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1. Absolute data presented for number of deaths as the confidence interval of the relative effect very large due to the small number of events. 2. Different measures presented ‐ mean or median change from baseline ‐ therefore data from all studies could not be pooled. 3. Quality of life data was collected in TWiTCH 2016; to date, primary results of this study have been published but not quality of life data. When available, quality of life data will be included in an update of this review. 4. Downgraded once due to applicability: only children with HbSS or HbSβº‐thalassemia were included therefore results are not applicable to adults or individuals with HbSC genotype. 5. Downgraded once due to imprecision: small number of events and large CI around the relative effect. 6. Downgraded once due to imprecision/uncertainty: caution is encouraged regarding the interpretation of these results due to the number of separate outcomes considered in analysis and the increased probability of a statistical type I error.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings ‐ Hydroxyurea compared with observation for people with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke.

| Hydroxyurea compared with observation for people with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with sickle cell disease and an increased risk of stroke Settings: outpatients Intervention: hydroxyurea Comparison: observation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Observation | Hydroxyurea | |||||

|

Pain alteration Follow‐up: NA |

Outcome not reported | NA | ||||

|

Life‐threatening illness Follow‐up: 15 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | No significant differences between groups in terms of ACS, blood transfusions required or acute splenic sequestration. |

|

Death during the study Follow‐up: 15 months |

No deaths occurred | No deaths occurred | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | |

|

Measures of HbF Follow‐up: 15 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | There was a significant increase in HbF in the hydroxyurea group compared to the observation group1. |

|

Measures of ANC Follow‐up: 15 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | There was a significant decrease in ANC in the hydroxyurea group compared to the observation group1. |

|

Quality of Life Follow‐up: NA |

Outcome not reported2 | NA | ||||

|

Adverse events or toxicity: differences in rates of specific adverse events Follow‐up: 15 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | No significant differences between groups in terms of transient neutropenia, reticulocytopenia, parasite infestation, headache and dizziness. |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the event rate in the control group unless otherwise stated in the comments and footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACS: acute chest syndrome; ANC: absolute neutrophil counts; CI: confidence interval; HbF: fetal haemoglobin; NA: not applicable; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1. Median values reported so data cannot be entered into analysis. 2. Outcome was not collected or presented due to early termination of study. 3. Downgraded twice due to serious imprecision: study terminated early with only 22 of target 100 participants recruited. Small number of participants included in final analyses which are likely to be underpowered. 4. Downgraded once due to applicability: only children with HbSS or HbSβº‐thalassemia were included therefore results are not applicable to adults or individuals with HbSC genotype.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings ‐ Hydroxyurea compared with no hydroxyurea for people with sickle cell disease.

| Hydroxyurea compared with no hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults and children with sickle cell disease Settings: outpatients Intervention: hydroxyurea Comparison: no hydroxyurea | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No hydroxyurea | Hydroxyurea | |||||

|

Pain alteration Follow‐up: NA |

Outcome not reported | NA | ||||

|

Life‐threatening illness Follow‐up: NA |

Outcome not reported | NA | ||||

|

Death during the study Follow‐up: 11 months |

No deaths occurred | No deaths occurred | NA | up to 44 (1 study)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

|

Measures of HbF Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

See comment | See comment | NA | up to 44 (1 study)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | There was a significant increase in HbF in the hydroxyurea group compared to the no hydroxyurea group1. |

|

Measures of ANC Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

See comment | See comment | NA | up to 44 (1 study)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | There was no significant difference in ANC between treatment groups1. |

|

Quality of life Follow‐up: NA |

Outcome not reported | NA | ||||

|

Adverse events or toxicity Follow‐up: 11 months |

See comment | See comment | NA | up to 44 (1 study)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | Vaso‐occlusive pain crises, headache / migraine, upper respiratory infection, skin rash diarrhoea and abdominal pain were the most common adverse events during the trial and these events were evenly distributed across treatment groups (not separated by group). |

| The basis for the assumed risk is the event rate in the control group unless otherwise stated in the comments and footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ANC: absolute neutrophil counts; CI: confidence interval; HbF: fetal haemoglobin; NA: not applicable; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1. Due to the factorial design of the study (22 participants randomised to a treatment arm including hydroxyurea and 22 randomised to a treatment arm without hydroxyurea), results are not entered into analysis. All results of this trial are considered exploratory (CHAMPS 2011). 2. Downgraded once due to indirectness: factorial design of the study makes comparison of hydroxyurea to no hydroxyurea indirect. 3. Downgraded once due to imprecision and risk of bias: study was terminated early with only 44 out of 188 participants recruited and outcome data is presented for only those who completed each follow‐up time. 4. Downgraded once due to applicability: participants with HbSC were included therefore results are not applicable to individuals with HbSS or HbSβº‐thalassemia genotypes.

Hydroxyurea compared to placebo for participants with SCD

Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

Hydroxyurea compared to observation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

Hydroxyurea compared to no hydroxyurea for participants with SCD

The following outcomes were reported in all tables (chosen based on relevance to clinicians and consumers): pain alteration; life‐threatening illnesses; deaths during the study; measures of fetal haemoglobin (HbF or F cells) and neutrophil counts, quality of life and adverse events or toxicity.

We determined the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach; and downgraded evidence in the presence of a high risk of bias in at least one study, indirectness of the evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of results, high probability of publication bias. We downgraded evidence by one level if we considered the limitation to be serious and by two levels if very serious.

For clarity in the tables, where outcomes were presented using different measures (e.g. pain alteration) or different domains (e.g. quality of life or adverse events), a general statement is made in the table regarding the summary of findings for these outcomes and the evidence is graded based on all of the measures or sub domains combined.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

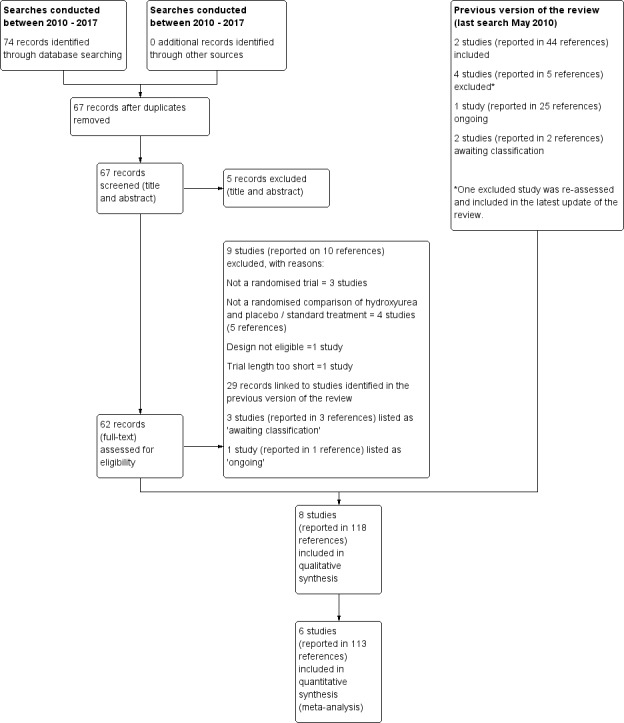

See Figure 1 for PRISMA study flow diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

The previous versions of the review (Jones 2001, latest search conducted May 2010) included two studies reported in 44 references (Belgian Study 1996; MSH 1995); additionally, one ongoing study (23 references) was identified (now completed) (BABY HUG 2011). Furthermore, two studies (two references) were listed as awaiting classification (CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012).

Searches conducted between June 2010 and January 2017 identified 74 records, seven of which were duplicates. Following removal of these, 67 records were screened and five clearly irrelevant records were excluded based on title and abstract. The remaining 62 records were further screened, full texts were accessed where possible. A total of 29 records were linked to studies previously identified (BABY HUG 2011; Belgian Study 1996; CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012; MSH 1995), nine studies (reported in 10 references) were excluded (see Excluded studies for further details), three studies (reported in three references) were listed as 'awaiting classification' due to uncertainties around the study design and population (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for further details) and one study (reported in one reference) was listed as 'ongoing' (see Characteristics of ongoing studies for further details).

The remaining 19 references corresponded to three new studies which were eligible for inclusion (SCATE 2015; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016) and one reference previously excluded from the previous version of the review (Ware 2006) was re‐assessed and included under the SWiTCH study (SWiTCH 2012). The three studies previously identified as ongoing or awaiting classification are now also eligible for inclusion in the review (BABY HUG 2011; CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012)

In total, eight studies (reported in 118 references) are included in the review (BABY HUG 2011; Belgian Study 1996; CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012; MSH 1995; SCATE 2015; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016).

Included studies

Eight studies are included, with a total of 899 children and adults (BABY HUG 2011; Belgian Study 1996; CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012; MSH 1995; SCATE 2015; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016)

The BABY HUG study was a multicentre, randomised, controlled study conducted in 13 centres in the USA (BABY HUG 2011). It was conducted in children aged nine months to 18 months who had haemoglobin SS (HbSS) or haemoglobin Sβºthalassaemia (HbSβºthal). Participants received liquid hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg per day) or matching placebo for two years administered as an oral syrup. A total of 193 children were randomised, 96 were randomised to the hydroxyurea group and 97 were randomised to the placebo group. Participants, caregivers and medical coordinating centre staff were masked to treatment allocation and an unmasked "primary end‐point person" monitored laboratory values and assisted in clinical management.

The Belgian Study was conduced in a single centre in Belgium (Belgian Study 1996). This involved 25 children and young adults with HbSS genotype with the aim of reviewing the impact on pain events, hospitalisation and also on fetal haemoglobin reactivation. This study was also placebo‐controlled, randomised and blinded to the participant but not to the caring physician. In addition, this was a cross‐over study which started at 20 mg/kg per day and, unless cytopenia developed this was raised to a maximum of 25 mg/kg per day. In this study the participants were randomised to either hydroxyurea or placebo for the initial six months and then crossed over to the other arm. There was no statistically significant period or carry‐over effect present for the outcomes of the number of hospitalisations and the number of days in hospital (period and carry‐over effects assessed by the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test).

The CHAMPS study was a randomised multicentre, phase II, double blind placebo‐controlled study with a 2x2 factorial design (CHAMPS 2011). Eligible participants were over the age of five years with HbSC and at least one vaso‐occlusive event in the previous 12 months (but none in the four weeks prior to study entry). A total of 44 participants were randomised equally across four treatment groups for 44 weeks: hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg per day) and magnesium (0.6 mmol/kg per day in two doses), hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg per day) and placebo, placebo and magnesium (0.6 mmol/kg per day in two doses), placebo and placebo. The study was not designed to measure efficacy and measured only laboratory measures.The study was terminated early due to low enrolment after 44 participants had been randomised (target 188).

The Jain study was a double blind (participants, personnel and outcome assessors) randomised controlled study conducted in a tertiary hospital in Nagpur City, India (Jain 2012). The study was conducted in children with sickle cell anaemia (proportion with each genotype not stated) between the ages of five and 18 years with three or more blood transfusions or vaso‐occlusive crises requiring hospitalisation per year despite high HbF. A total of 60 participants were randomised; 30 to hydroxyurea (fixed dose 10 mg/mg per day) and 30 to a matched placebo for 18 months.

The MSH study was a multicentre North American randomised and double‐blind study, which compared hydroxyurea with placebo over two years in adults with sickle cell anemia (SS genotype only) with the objective of reducing the frequency pain crises (MSH 1995). A total of 299 participants were randomised; 152 to hydroxyurea and 147 to matching placebo. Hydroxyurea was started at low dose (15 mg/kg per day) and increased at 12‐weekly intervals by 5 mg/kg per day until mild bone marrow depression, as judged by either neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, at that point the treatment was stopped (as reported for the MSH study) (Handy 1996). Once the blood count had recovered, treatment was restarted at 2.5 mg/kg per day less than the toxic dose. The study was therefore aiming for the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for each individual within the study. The study was blinded and the study centre recorded and held the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and HbF levels, which were not looked at by the caring physicians as the MCV and HbF levels rise in most people with SS taking hydroxyurea. As a result of the beneficial effects observed in terms of the primary pain outcome, as reported for the MSH study (Barton 1996), the study was stopped by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the USA at a mean follow‐up of 21 months, before the planned 24 months of treatment had been completed for all participants (MSH 1995). Long‐term follow‐up continued for the study sample, with all participants offered treatment with hydroxyurea.

The SCATE (Sparing Conversion to Abnormal transcranial doppler (TCD) Elevation) study was a Phase III multicentre, randomised, controlled study conducted in three centres in the USA, Jamaica and Brazil (SCATE 2015). The study was conducted in children with sickle cell anemia (SS, Sβº, HbSOArab, HbSD), haemoglobin SS (HbSS) or haemoglobin Sβº thalassaemia and conditional TCD ultrasound velocities (170 cm to 199 cm per second). A total of 22 participants were randomised; 11 to hydroxyurea at 20 mg/kg with escalation to maximum dose of 35 mg/kg and 11 to standard treatment (observation). The primary aim of the study was to establish whether treatment with hydroxyurea could prevent conversion from conditional to abnormal time averaged mean velocity (TAMV) and subsequent stroke in these children. The planned length of follow‐up was 30 months but the study was terminated after 15 months of follow‐up due to slow participant accrual and the unlikelihood of meeting the trial recruitment target (100) and the primary endpoint.

The SWiTCH study was a non‐inferiority study, comparing hydroxyurea and phlebotomy to standard treatment (transfusion and chelation) using a composite endpoint including secondary stroke prevention and improved management of iron overload. It included children with SCA (HbSS and HbSβºthal, HbSOArab) and previous stroke, who had been receiving chronic transfusions for at least 18 months (SWiTCH 2012). It was conducted in 26 sickle cell centres across the USA and a total of 134 children were randomised (67 to the standard treatment and 67 to the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group). Participants randomised to hydroxyurea and phlebotomy commenced hydroxyurea at 20 mg/kg with escalation to MTD (defined by dose causing mild myelosuppression). Transfusion continued for four to nine months during hydroxyurea dose escalation. Once MTD was reached and transfusion stopped, phlebotomy of 10 mL/kg monthly was performed, if haemoglobin was sufficient.

The TWiTCH study was a multicentre phase III randomised open label (partially masked) non‐inferiority study conducted at 26 paediatric hospitals and health centres in the USA and Canada (TWiTCH 2016). Eligible participants were children aged four to 16 years with SCA (HbSS, HbSβºthal, HbSOArab) and abnormal TCD ultrasound velocities (≥ 200 cm per second) if they had received 12 months of chronic transfusions. A total of 121 participants were randomised; 60 to hydroxyurea starting at 20 mg/kg per day escalated to the MTD compared to standard treatment (transfusions) for 24 months. Children randomised to the standard treatment group received their usual chelation therapy or deferasirox to manage iron overload. Children randomised to the hydroxyurea group continued to receive transfusions until hydroxyurea was escalated to the MTD and following the discontinuation of transfusions, children received serial phlebotomy to manage iron overload. The primary aim of the study was to establish whether treatment with hydroxyurea could prevent primary stroke in these children. The study was terminated at the first interim analysis when non‐inferiority was demonstrated; the target sample size had been recruited by this point.

Excluded studies

Following the 2010 search for the previous version of the review (Jones 2001), four studies (reported in five references) were excluded from the review (De Montalembert 2006; Silva‐Pinto 2007; Voskaridou 2005; Ware 2006). However, as described above (Results of the search), for the present version of the review, the Ware reference was reassessed and included under the SWiTCH study (SWiTCH 2012).

In total, 12 studies (14 references) were excluded from the current review; five were not randomised (Al‐Nood 2011; Pushi 2000; Silva‐Pinto 2007; Silva‐Pinto 2014; Voskaridou 2005), four did not make a randomised comparison of hydroxyurea and placebo or standard treatment (George 2013; NCT00004492; NCT01960413; Vichinsky 2013), two were of one week of less duration (De Montalembert 2006; NCT01848925) and one was an inappropriate design for measuring the effectiveness of hydroxyurea (NCT02149537).

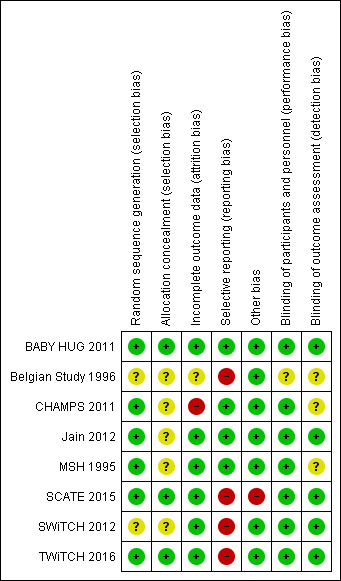

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Characteristics of included studies for more information.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

One study used an automated telephone response system to randomise participants using lists that had been produced by the medical co‐ordinating centre (BABY HUG 2011). The SCATE and TWiTCH studies used blocked randomisation and central pharmacy allocation (SCATE 2015;TWiTCH 2016 ). All three studies have been assessed as having a low risk of bias.

The MSH study used computerised block randomisation, the Jain trial used random number tables and the CHAMPS study used a sequential allocation algorithm for randomisation (low risk of bias) but none of these studies clearly stated any method of allocation concealment (unclear risk of bias) (CHAMPS 2011; Jain 2012; MSH 1995).

The Belgian study described the randomisation of participants as "drawing sealed envelopes, patients were randomly allocated to one of the following treatment sequences", therefore, the generation and the allocation of the treatment sequence are not clear from this statement (Belgian Study 1996). The hospital pharmacy provided the treatment and placebo for each participant and both were described as "indistinguishable." The SWiTCH trial did not discuss the method for randomisation or allocation concealment and therefore this has been graded as unclear (SWiTCH 2012).

Blinding

The BABY HUG study was described as 'double blind', the study paper stated that "participants, caregivers and medical coordinating centre staff were masked to treatment allocation" (BABY HUG 2011). The hydroxyurea and placebo powders were identical in terms of appearance and packaging and the liquid formulations had the same appearance and taste. In the Jain study, participants, clinicians and outcome assessors including laboratory technicians were blinded to treatment allocation with placebo capsules of identical appearance (Jain 2012). These studies were assessed as low risk of performance and detection bias.

In three studies, the blinding of participants and personnel was also not possible due to the differences between the treatments (hydroxyurea and standard treatment) (SCATE 2015; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016). Outcome assessors were partially masked in these studies for assessments around the primary outcomes related to neurological events such as stroke. Given the objective nature of the primary outcomes of the studies judged by the blinded outcome assessors, these studies were assessed as low risk of detection bias.

The MSH study was described as double blind (physician and participant) (MSH 1995) and in the CHAMPS study, treatment was assigned in combinations of identically appearing capsules and blinding was achieved by 'over‐capsulating' tablets (CHAMPS 2011). These two studies were assessed as low risk of performance bias. The Belgian study was single‐blinded (the participant was unaware of the treatment schedule but the physician was aware of the treatment schedule) because of the difficulty of blinding the attending physician to the treatment received (Belgian Study 1996). It was not stated whether outcome assessors were blinded in any of these three studies.

Incomplete outcome data

In four studies, the risk of bias was assessed as low since withdrawals from treatment were documented, an intention‐to‐treat analysis approach in primary analyses was used and all randomised participants were included in the analysis (Jain 2012; MSH 1995; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016).

In the BABY HUG study, an intention‐to‐treat analysis was undertaken for primary outcomes (via multiple imputation methods to account for missing data) and for safety outcomes (BABY HUG 2011). Some of the secondary outcomes were reported for only the individuals who completed the study or had data recorded for specific measurements, but given that primary and important safety outcomes were reported using an intention‐to‐treat analysis, this study was judged to be at a low risk of bias.

In the SCATE study, due to the early termination of the study, two randomised participants did not receive their allocated treatment (SCATE 2015). The primary analysis of this study used an intention‐to‐treat approach and a sensitivity analysis considered the actual treatment received so this study was also assessed as having a low risk of bias.

In the Belgian study, three participants were excluded from the analysis due to their failure to attend their monthly evaluation at four to five months (Belgian Study 1996). There was no discussion of whether or not an intention‐to‐treat analysis was used, therefore, the risk of bias was judged to be unclear.

In the CHAMPS study, only participants who completed eight weeks (primary outcome) or 44 weeks (secondary outcomes) of follow‐up were included in the results (CHAMPS 2011). This is not an intention‐to‐treat approach so this trial was judged to be at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Three studies defined outcomes in their methods sections, which were reported in the results, and were thus assessed as having a low risk of bias (BABY HUG 2011; Jain 2012; MSH 1995). The CHAMPS study was not designed to measure efficacy and reported only laboratory‐based outcomes; all of these outcomes were well‐defined in the methods and reported in the results, so this study was assessed to be at a low risk of bias (CHAMPS 2011).

In the primary publication of the TWiTCH study, it was stated the the secondary outcomes of neuropsychological status, quality of life and growth would be published at a later date (TWiTCH 2016). For the SWiTCH study, some outcomes (such as growth and development, functional evaluations, neurocognitive evaluations) do not yet seem to have been reported (SWiTCH 2012). As we are not able to include the results at this time, we have judged these studies to be at a high risk of selective reporting bias. If these results can be included at a later date then this judgement will be reconsidered (SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016). The final two studies planned to measure outcomes which were not reported due to difficulty in collecting the information to inform these outcomes; these studies are also judged to be at a high risk of bias (Belgian Study 1996; SCATE 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

One study was likely to be underpowered due to the early termination of the study with only 22% of the target sample size recruited (SCATE 2015). Another study recruited only 23% of the target sample size (CHAMPS 2011); however; this study was not designed to measure efficacy and analyses were intended to be exploratory, so we did not consider this study to be at high risk of bias. Another study was also terminated early at the first interim analysis, but the target sample size had been recruited at this point so we did not consider this study to be at a high risk of bias (TWiTCH 2016).

No other bias was identified for the remaining studies (BABY HUG 2011; Belgian Study 1996; Jain 2012; MSH 1995; SWiTCH 2012).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

For the 2017 update of the review six new studies were included (BABY HUG 2011; Jain 2012; CHAMPS 2011; SCATE 2015; SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016). Due to differences in the eligible populations and treatments in these new studies, we have made the following comparisons.

1. Hydroxyurea compared to placebo for participants with SCD

This comparison includes four studies (BABY HUG 2011; Belgian Study 1996; Jain 2012; MSH 1995).

2. Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

This comparison includes two studies (SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016).

3. Hydroxyurea compared to observation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

This comparison includes a single study (SCATE 2015).

4. Hydroxyurea compared to no hydroxyurea for participants with SCD

This comparison includes a single study (CHAMPS 2011). We note that this study recruits only individuals with HbSC; however, this comparison (and other comparisons) are worded to allow for future studies to be included in updates of this review which recruit individuals of all genotypes to contribute to this comparison.

We have conducted meta‐analyses for comparisons 1 and 2 (above) where appropriate and presented results narratively or in additional tables (Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8). Data are not entered into analysis for the Belgian and CHAMPS studies due to the presentation of results from cross‐over and factorial designs respectively; results are reported narratively (Belgian Study 1996; CHAMPS 2011). Long‐term follow‐up of the participants in MSH study continued for up to 17 years and many publications presented results of long‐term follow‐up (see linked reference list of the MSH study) (MSH 1995). After two years of double‐blind, placebo‐controlled therapy, all participants were offered hydroxyurea therapy, so any results reported after the MSH study period are uncontrolled. The long‐term results are not therefore analysed in this review.

1. Clinical events and markers of response in Jain 2012.

| Hydroxyurea | Placebo | P value | |||

| Baseline | 18 months | Baseline | 18 months | ||

| Clinical events (number of events per participant per year) | |||||

| VOC | 12.13 (8.56) | 0.60 (1.37) | 11.46 (3.01) | 10.2 (3.24) | < 0.001 |

| Blood transfusions | 2.43 (0.69) | 0.13 (0.43) | 2.13 (0.98) | 1.98 (0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalisations | 10.13 (6.56) | 0.70 (1.28) | 9.56 (2.91) | 9.59 (2.94) | < 0.001 |

| Haematological parameters | |||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.1 (0.68) | 9.29 (0.55) | 8.21 (0.68) | 7.90 (0.58) | < 0.001 |

| HbF(%) | 19.8 (0.9) | 24 (5.9) | 19.21 (6.37) | 18.92 (5.77) | < 0.001 |

| Reticulocytes (x10⁵ /mm³) | 1.83 (0.96) | 1.15 (0.1) | 1.73 (0.49) | 1.81 (0.67) | < 0.001 |

| Leucocytes (x10³ /mm³) | 7.36 (6.03) | 6.54 (5.54) | 7.26 (4.91) | 7.38 (2.85) | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (x10³ /mm³) | 1.78 (0.26) | 2.01 (0.18) | 1.91 (0.21) | 2.06 (0.26) | 0.28 |

| RBC (x10⁶ /mm³) | 2.89 (0.57) | 1.98 (0.22) | 1.84 (0.47) | 3.11 (0.20) | 0.05 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.32 (1.42) | 1.10 (0.42) | 2.27 (1.28) | 2.71 (0.93) | < 0.001 |

Values are mean (standard deviation) P values are calculated using independent t‐test.

Hb: haemoglobin HbF: fetal haemoglobin RBC: red blood count VOC: vaso‐occlusive crises WBC: white blood count

2. Laboratory measurements from MSH 1995.

| Baseline | Hyrdoxyurea | Placebo | P value | ||

| 2 years | Baseline | 2 years | 2 years | ||

| WBC (10⁹/L) | 12.6 (3.4) | 9.9 (3.1) | 12.3 (3.2) | 12.2 (2.8) | 0.0001 |

| Neutrophils (10⁹/L) | 6.9 (2.4) | 4.9 (2.0) | 6.7 (2.3) | 6.4 (2.0) | 0.0001 |

| Platelets (10⁹/L) | 468 (147) | 399 (124) | 457 (130) | 423 (122) | 0.12 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.5 (1.4) | 9.1 (1.5) | 8.5 (1.2) | 8.5 (1.3) | 0.0009 |

| PCV (%) | 24.9 (4.4) | 27 (5) | 25.2 (4.0) | 25.1 (4.2) | 0.0007 |

| MCV (fl) | 94 (9) | 103 (14) | 93 (9) | 93 (9) | 0.0001 |

| Reticulocytes (10⁹/L) | 327 (98) | 231 (100) | 325 (94) | 300 (99) | 0.0001 |

| HbF (%) | 5 (3.5) | 8.6 (6.8) | 5.2 (3.4) | 4.7 (3.3) | 0.0001 |

| F cells (%) | 33 (17) | 48 (23) | 33 (17) | 35 (18) | 0.0001 |

| F reticulocytes | 15 (8) | 17 (9) | 15 (8) | 15 (7) | 0.0036 |

| Dense cells (%) | 14 (6) | 11 (6) | 14 (7) | 13 (7) | 0.004 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.64 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.7 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.5) | 4.2 (4.6) | 0.004 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.7 (2.2) | 0.08 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 44 (23) | 39 (20) | 41 (21) | 43 (27) | 0.16 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 120 (59) | 117 (48) | 119 (67) | 119 (71) | 0.71 |

Values are mean (standard deviation) P values are calculated using independent t‐test.

Hb: haemoglobin HbF: fetal haemoglobin MCV: mean corpuscular volume PCV: packed cell volume WBC: white blood count

3. Laboratory evaluations from the SWiTCH trial.

| Outcome |

Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group (n = 67) |

Transfusions and chelation group (n = 66) |

P value |

| HbF (%) | 17.9 (92 to 22.9) | ‐0.2 (‐0.8 to 0.4) | < 0.001 |

| ANC (x10⁹/L) | ‐3.3 (‐5.1 to ‐1.4) | 0.8 (‐1.3 to 2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hb (g /dL) | 0.0 (‐0.7 to 0.7) | 0.0 (‐0.5 to 0.6) | 0.898 |

| HbA (%) | ‐50.9 (‐66.8 to ‐33.7) | 0.0 (‐12.7 to 6.7) | < 0.001 |

| HbS (%) | 35.0 (21.7 to 46.2) | 0.3 (‐7.5 to 12.3) | < 0.001 |

| MCV (fL) | 19.5 (7.5 to 28.5) | 0.1 (‐2.0 to 2.5) | < 0.001 |

| WBC (x10⁹/L) | ‐5.4 (‐8.1 to ‐2.2) | 0.2 (‐2.0 to 2.3) | < 0.001 |

| ARC (x10⁹/L) | ‐149.1 (‐231.0 to ‐19.0) | ‐11.8 (‐88.2 to 93.2) | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (x10⁹/L) | ‐83.0 (‐171.0 to ‐8.0) | ‐28.0 (‐70.0 to 18.0) | 0.0022 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ‐1.1 (‐1.9 to ‐0.6) | 0.4 (‐0.3 to 1.2) | < 0.001 |

| LIC (mg Fe/g) | ‐1.2 (‐2.8 to 7.2) | ‐2.2 (‐5.5 to 4.9) | 0.48888 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL) | ‐966.0 (‐1629.0 to 49.0) | 1159.5 (‐662.0 to 2724.0) | < 0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | ‐67.0 (‐143.0 to 7.0) | ‐8.5 (‐74.0 to 74.0) | 0.0015 |

ANC: absolute neutrophil count ARC: absolute reticulocyte count Hb: haemoglobin HbA: adult haemoglobin HbF: fetal haemoglobin HbS: sickle haemoglobin LDH: lactate dehydrogenase LIC: liver iron concentration MCV: mean corpuscular volume WBC: white blood count

Values are median change from baseline and interquartile range. P values are calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum test.

4. Laboratory evaluations from the SCATE trial.

| Outcome | Hydroxyurea (n = 11) | Observation (n = 11) | P value |

| Hb (g/dL) | 1.6 | ‐0.5 | < 0.0001 |

| MCV (fL) | 8.7 | 1 | 0.0001 |

| ARC ( x10⁹/L) | 22.7 | ‐33.2 | 0.76 |

| WBC ( x10⁹/L) | ‐4.6 | 1.3 | 0.07 |

| ANC ( x10⁹/L) | ‐2.2 | 1.4 | 0.05 |

| Platelets ( x10⁹/L) | ‐76 | ‐35 | 0.56 |

| HbF (%) | 8.9 | 0.3 | 0.002 |

| Weight (kg) | 2.5 | 1.8 | 0.51 |

| Height (cm) | 6.8 | 3.8 | 0.22 |

ANC: absolute neutrophil count ARC: absolute reticulocyte count Hb: haemoglobin HbF: fetal haemoglobin MCV: mean corpuscular volume WBC: white blood count.

Values are median change from baseline and P values are calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Primary outcomes

1. Pain alteration

Hydroxyurea compared to placebo for participants with SCD

The MSH study defined pain crisis as a visit to a medical facility, lasting four or more hours, requiring opiate analgesia (MSH 1995). There was a statistically significant difference between the hydroxyurea group and placebo group in the mean annual crisis rate (all crises), MD ‐2.80 (95% CI ‐4.74 to ‐0.86) (P = 0.005) and for crises requiring hospitalisation, MD ‐1.50 (95% CI ‐2.58 to ‐0.42) (P = 0.007) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hydroxyurea versus placebo for participants with sickle cell disease, Outcome 1 Pain crises.

The MSH study also showed a reduction in median time (Kaplan‐Meier life table estimate) from the initiation of treatment to first painful crisis (2.76 months in the hydroxyurea arm compared with 1.35 months on placebo (Cox regression P value = 0.014), second painful crisis (6.58 months in the hydroxyurea group compared with 4.13 months on placebo (Cox regression P value < 0.0024), and third painful crisis (11.9 months in the hydroxyurea group compared with 7.04 months on placebo (Cox regression P value = 0.0002) (reported in Charache 1995). We note that the analysis of time‐to‐first, second and third painful crisis seems to treat crisis events independently which is unlikely to be a realistic assumption. Furthermore, information relating to the analgesia used by participants in this study has been reported, but has not been presented according to the groups to which the participants were randomised (reported in Ballas 1996).

The Jain study presented the number of clinical events (vaso‐occlusive crises) before and after intervention (Jain 2012). We could not calculate change from baseline in the number of clinical events so we have analysed between group data at 18 months and presented the before and after data in an additional table (Table 5). After 18 months of treatment, there was a statistically significant difference between the hydroxyurea group and placebo group, MD ‐9.60 (95% CI ‐10.86 to ‐8.34) (P < 0.00001) (Analysis 1.1).

The BABY HUG study showed a statistically significantly lower proportion of participants experiencing pain in the hydroxyurea group compared to the placebo group, RR 0.68 (95% CI 0.5 to 0.92) (BABY HUG 2011) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hydroxyurea versus placebo for participants with sickle cell disease, Outcome 2 Proportion experiencing pain.

The Belgian study stated that "16 patients out of 22 (73%) did not require any hospitalisation for painful episodes when treated with hydroxyurea as compared with only 3 of 22 (14%) when treated with placebo" (Belgian Study 1996). In addition, it showed as reduction in mean hospital stay, with a stay of 5.3 days in the hydroxyurea group and 15.2 days in the placebo group. A planned outcome of 'number of days in pain' was not reported in the trial publication due to difficulties in collecting this information from participants.

Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

Both studies reported the number of participants experiencing 'serious' vaso‐occlusive or sickle cell (SCA)‐related pain events (SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016) and one study also reported the number of participants experiencing any vaso‐occlusive or sickle cell (SCA)‐related pain event (SWiTCH 2012)

There was a statistically significantly higher proportion of participants experiencing serious vaso‐occlusive or sickle cell (SCA)‐related pain in the hydroxyurea and phlebotomy group compared to the transfusion and chelation groups in the SWiTCH and TWiTCH studies, pooled RR 3.37 (95% CI 1.59 to 7.11) (P = 0.001) (SWiTCH 2012; TWiTCH 2016), but there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of all SCA pain events in the SWiTCH study, RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.30) (P = 0.81) (SWiTCH 2012) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hydroxyurea and phlebotomy compared to transfusion and chelation for participants with SCD and risk of stroke, Outcome 1 Proportion experiencing pain.

Hydroxyurea compared to observation for participants with SCD and an increased risk of stroke

No information was reported for this outcome in the SCATE study (SCATE 2015).

Hydroxyurea compared to no hydroxyurea for participants with SCD

No information was reported for this outcome in the CHAMPS study (CHAMPS 2011).

2. Life‐threatening illness

Hydroxyurea compared to placebo for participants with SCD

The BABY HUG and the MSH studies provided data on the occurrence of acute chest syndrome, stroke and participants transfused (BABY HUG 2011; MSH 1995). Statistically significant advantages in the hydroxyurea group was the reduction in the occurrence of the acute sickle chest syndrome, pooled RR 0.43 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.63) (P < 0.0001), and also that fewer participants on hydroxyurea underwent transfusions, pooled RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.82) (P = 0.0003). There was no statistically significant difference in terms of stroke, pooled RR 0.54 (95% CI 0.12 to 2.53) (P = 0.44) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hydroxyurea versus placebo for participants with sickle cell disease, Outcome 3 Proportion experiencing life threatening events during study.

The MSH study reported data on hepatic sequestration and the BABY HUG study reported data on splenic sequestration, the differences between the groups were not statistically significant, RR 0.32 (95% CI 0.03 to 3.06) (P = 0.32) and RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.36 to 2.23) (P = 0.82), respectively (MSH 1995; BABY HUG 2011) (Analysis 1.3).

The Jain study presented the number of clinical events (blood transfusions and hospitalisations) before and after intervention (Jain 2012). We could not calculate change from baseline the number of clinical events so we have analysed between group data at 18 months and presented the before and after data in an additional table (Table 5). After 18 months of treatment, there was a statistically significant difference between the hydroxyurea group and placebo group in the number of blood transfusions, MD ‐1.85 (95% CI ‐2.18 to ‐1.52) (P < 0.00001) and in the number of hospitalisations, MD ‐8.89 (95% CI ‐10.04 to ‐7.74) (P < 0.00001). The duration of hospitalisation was also significantly less in the hydroxyurea group than the placebo group, MD ‐4.00 days (95% CI ‐4.87 to ‐3.13) (P < 0.00001) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hydroxyurea versus placebo for participants with sickle cell disease, Outcome 4 Number of life‐threatening events during study.