Abstract

Background

The treatment of multiple sclerosis has changed over the last 20 years. The advent of disease‐modifying drugs in the mid‐1990s heralded a period of rapid progress in the understanding and management of multiple sclerosis. With the support of magnetic resonance imaging early diagnosis is possible, enabling treatment initiation at the time of the first clinical attack. As most of the disease‐modifying drugs are associated with adverse events, patients and clinicians need to weigh the benefit and safety of the various early treatment options before taking informed decisions.

Objectives

1. to estimate the benefit and safety of disease‐modifying drugs that have been evaluated in all studies (randomised or non‐randomised) for the treatment of a first clinical attack suggestive of MS compared either with placebo or no treatment;

2. to assess the relative efficacy and safety of disease‐modifying drugs according to their benefit and safety;

3. to estimate the benefit and safety of disease‐modifying drugs that have been evaluated in all studies (randomised or non‐randomised) for treatment started after a first attack ('early treatment') compared with treatment started after a second attack or at another later time point ('delayed treatment').

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the CNS Group Trials Register, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, clinicaltrials.gov, the WHO trials registry, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reports, and searched for unpublished studies (until December 2016).

Selection criteria

We included randomised and observational studies that evaluated one or more drugs as monotherapy in adult participants with a first clinical attack suggestive of MS. We considered evidence on alemtuzumab, azathioprine, cladribine, daclizumab, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, glatiramer acetate, immunoglobulins, interferon beta‐1b, interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®, Avonex®), laquinimod, mitoxantrone, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, pegylated interferon beta‐1a, rituximab and teriflunomide.

Data collection and analysis

Two teams of three authors each independently selected studies and extracted data. The primary outcomes were disability‐worsening, relapses, occurrence of at least one serious adverse event (AE) and withdrawing from the study or discontinuing the drug because of AEs. Time to conversion to clinically definite MS (CDMS) defined by Poser diagnostic criteria, and probability to discontinue the treatment or dropout for any reason were recorded as secondary outcomes. We synthesized study data using random‐effects meta‐analyses and performed indirect comparisons between drugs. We calculated odds ratios (OR) and hazard ratios (HR) along with relative 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all outcomes. We estimated the absolute effects only for primary outcomes. We evaluated the credibility of the evidence using the GRADE system.

Main results

We included 10 randomised trials, eight open‐label extension studies (OLEs) and four cohort studies published between 2010 and 2016. The overall risk of bias was high and the reporting of AEs was scarce. The quality of the evidence associated with the results ranges from low to very low.

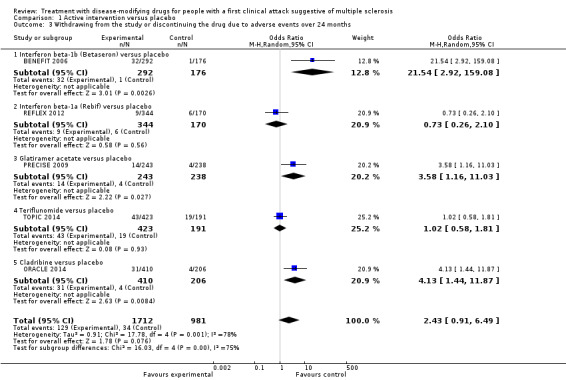

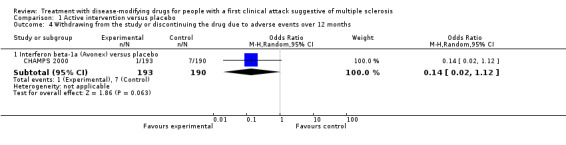

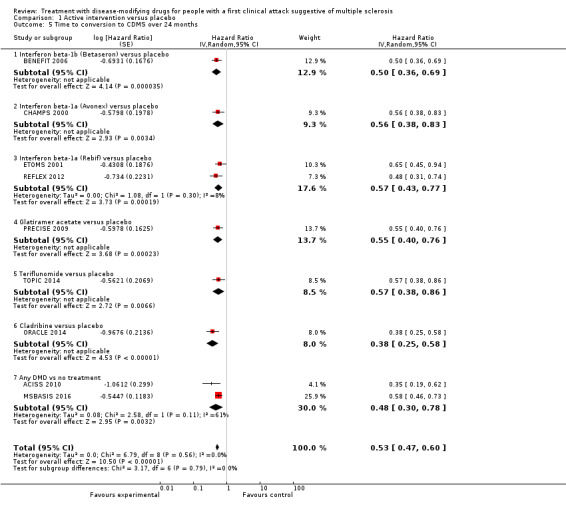

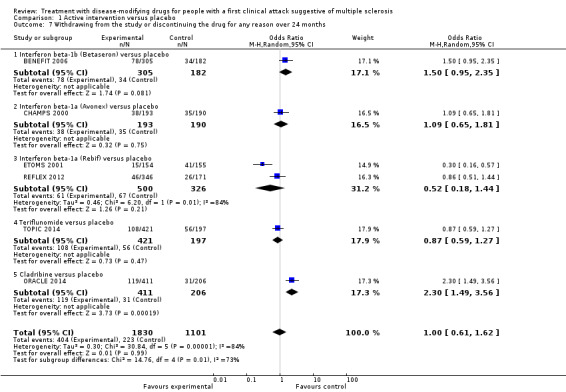

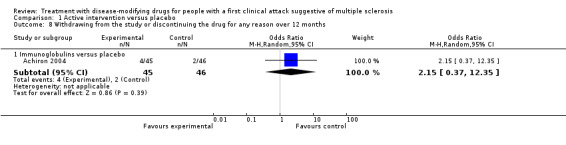

Early treatment versus placebo during the first 24 months' follow‐up

There was a small, non‐significant advantage of early treatment compared with placebo in disability‐worsening (6.4% fewer (13.9 fewer to 3 more) participants with disability‐worsening with interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®) or teriflunomide) and in relapses (10% fewer (20.3 fewer to 2.8 more) participants with relapses with teriflunomide). Early treatment was associated with 1.6% fewer participants with at least one serious AE (3 fewer to 0.2 more). Participants on early treatment were on average 4.6% times (0.3 fewer to 15.4 more) more likely to withdraw from the study due to AEs. This result was mostly driven by studies on interferon beta 1‐b, glatiramer acetate and cladribine that were associated with significantly more withdrawals for AEs. Early treatment decreased the hazard of conversion to CDMS (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.60).

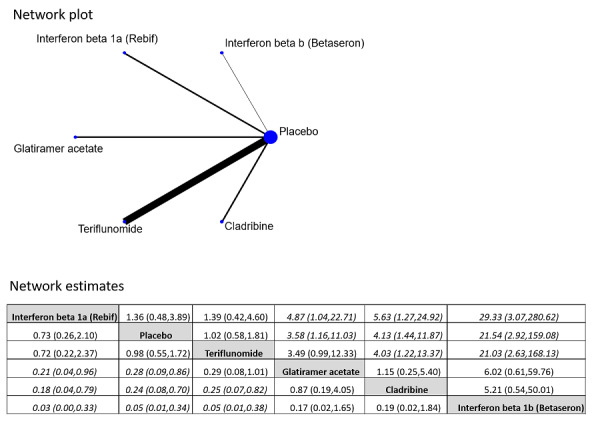

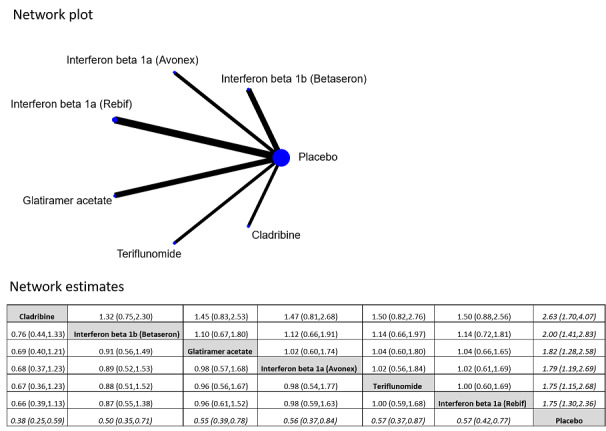

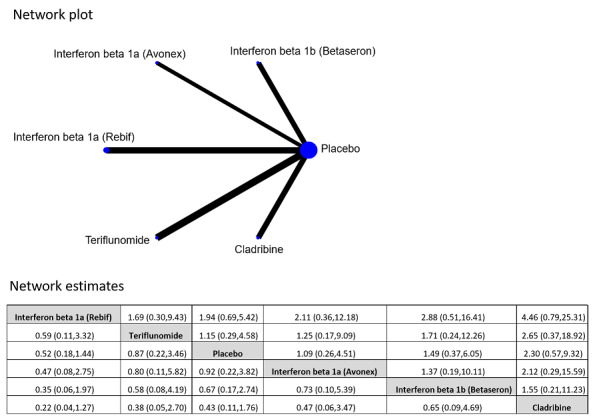

Comparing active interventions during the first 24 months' follow‐up

Indirect comparison of interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®) with teriflunomide did not show any difference on reducing disability‐worsening (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.66). We found no differences between the included drugs with respect to the hazard of conversion to CDMS. Interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®) and teriflunomide were associated with fewer dropouts because of AEs compared with interferon beta‐1b, cladribine and glatiramer acetate (ORs range between 0.03 and 0.29, with substantial uncertainty).

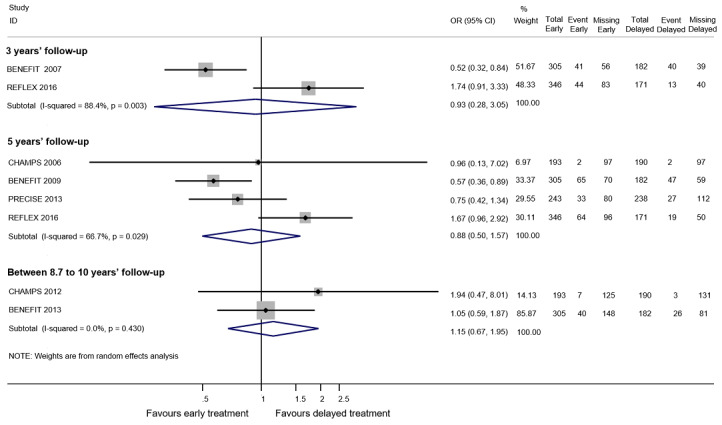

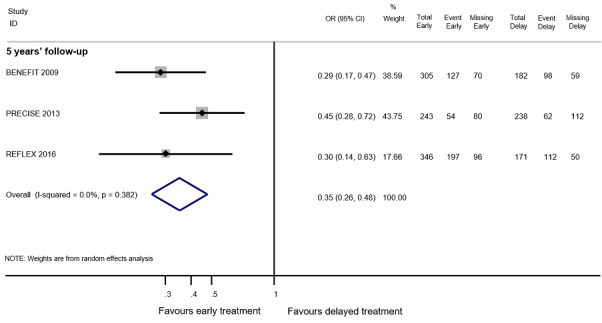

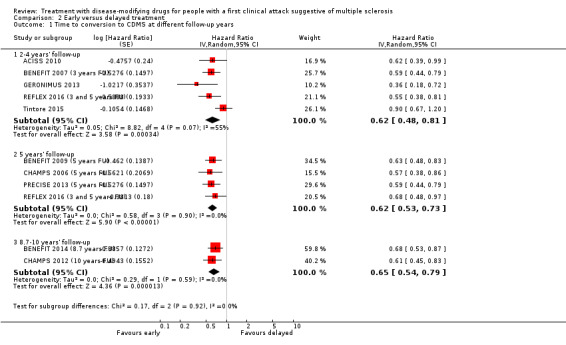

Early versus delayed treatment

We did not find evidence of differences between early and delayed treatments for disability‐worsening at a maximum of five years' follow‐up (3% fewer participants with early treatment (15 fewer to 11.1 more)). There was important variability across interventions; early treatment with interferon beta‐1b considerably reduced the odds of participants with disability‐worsening during three and five years' follow‐up (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.84 and OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.89). The early treatment group had 19.6% fewer participants with relapses (26.7 fewer to 12.7 fewer) compared to late treatment at a maximum of five years' follow‐up and early treatment decreased the hazard of conversion to CDMS at any follow‐up up to 10 years (i.e. over five years' follow‐up HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.73). We did not draw any conclusions on long‐term serious AEs or discontinuation due to AEs because of inadequacies in the available data both in the included OLEs and cohort studies.

Authors' conclusions

Very low‐quality evidence suggests a small and uncertain benefit with early treatment compared with placebo in reducing disability‐worsening and relapses. The advantage of early treatment compared with delayed on disability‐worsening was heterogeneous depending on the actual drug used and based on very low‐quality evidence. Low‐quality evidence suggests that the chances of relapse are less with early treatment compared with delayed. Early treatment reduced the hazard of conversion to CDMS compared either with placebo, no treatment or delayed treatment, both in short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. Low‐quality evidence suggests that early treatment is associated with fewer participants with at least one serious AE compared with placebo. Very low‐quality evidence suggests that, compared with placebo, early treatment leads to more withdrawals or treatment discontinuation due to AEs. Difference between drugs on short‐term benefit and safety was uncertain because few studies and only indirect comparisons were available. Long‐term safety of early treatment is uncertain because of inadequately reported or unavailable data.

Plain language summary

Disease‐modifying drugs for people with a first clinical attack suggestive of multiple sclerosis

This summary presents data about the benefit and side effects of some disease‐modifying drugs used at the time when multiple sclerosis is diagnosed after a first clinical attack. We reviewed the available evidence to answer three questions: 1) is early treatment beneficial and safe? 2) which drug is best for early treatment? 3) is early treatment better than later treatment?

Sufficient data were available from 22 studies on the following drugs: cladribine (Movectro), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), interferon beta‐1b (Betaferon), interferon beta‐1a (Rebif; Avonex), and teriflunomide (Aubagio).

First question: is early treatment beneficial and safe?

Disability‐worsening Among people who took Aubagio or Rebif, 28 people out of 100 experienced disability‐worsening over two years’ treatment compared to 34 people out of 100 who took placebo (6% absolute benefit). The overall quality of the included studies is very low, so our confidence in this result is low.

Relapse Early treatment was associated with lower proportions of people who had a second attack ‐ ie who received a diagnosis of MS ‐ during the first two years' treatment, compared to people who took placebo. Among people who took Aubagio, 32 people out of 100 experienced recurrent relapses over two years’ treatment compared to 42 people out of 100 who took placebo (10% absolute benefit). Again, the overall quality of evidence is very low.

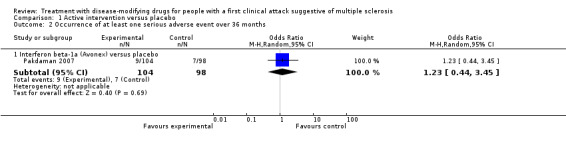

Serious side effects Among people who took Aubagio, Avonex, Betaferon, Copaxone, Movectro, or Rebif, there is probably little or no difference in serious side effects over two years’ treatment compared with people who took placebo.

Side effects Among people who took Betaferon, 11 people out of 100 experienced side effects compared to one person out of 100 people who took placebo (10% absolute harm). Among people who took Movectro, seven people out of 100 experienced side effects compared to two out of 100 people who took placebo (5% absolute harm). Among people who took Copaxone, six people out of 100 experienced a side effect compared to two out of 100 people who took placebo (4% absolute harm).

Second question: which drug is best for early treatment?

Disability‐worsening Indirect comparison of Rebif with Aubagio did not show any difference on reducing disability‐worsening over two years’ treatment. However, there were few studies and the overall quality of evidence is very low.

Relapse

Only one study on Aubagio was available, so we cannot compare the effects of each drug compared with one other.

Side effects Rebif and Aubagio were associated with fewer dropouts because of side effects compared with Betaferon, Copaxone, or Movectro.

Third question: is early treatment better than later treatment?

Disability‐worsening Among people who received early treatment with Avonex, Betaferon, Copaxone, or Rebif, 37 people out of 100 experienced disability‐worsening at a maximum of five years’ follow‐up compared with 40 people out of 100 who received later treatment (3% absolute benefit). However, the great variability between the studies and the low quality of the evidence make our confidence in this result low.

Relapse Early treatment was associated with lower proportions of people who had a second attack at any follow‐up up to 10 years, compared to people who received later treatment. Among people who received early treatment with Betaferon, Copaxone, or Rebif, 64 people out of 100 experienced recurrent relapses at a maximum of five years’ follow‐up compared to 83 people out of 100 who received these drugs later (19% absolute benefit).

Side Effects We did not draw any conclusions on long‐term serious side effects or treatment discontinuation due to side effects because of inadequacies in the available data in the included studies.

Conclusion

The low‐quality evidence of the included studies suggests a small and uncertain benefit with early treatment compared with placebo or later treatment in reducing disability‐worsening and relapses.

We cannot draw conclusions on the long‐term safety of these drugs when administered as early treatment because of inadequately reported or unavailable data.

Until convincing evidence of any difference on benefit between disease‐modifying drugs becomes available, the drugs that have been in use in clinical practice for many years and whose safety profile is better understood are probably the most sensible choice for early treatment.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Are disease‐modifying drugs for a first attack suggestive of multiple sclerosis (MS) effective and safe compared to placebo?

| Patient: adults with first attack suggestive of MS Setting: MS centres Intervention: early disease‐modifying drug treatment Comparison: placebo | |||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | |||

| With placebo | With early disease‐modifying drugs treatment | Difference | |||||

|

Disability‐worsening Proportion of participants with disability‐worsening, assessed by EDSS** during 24 months of treatment Participants: N = 927 (2 RCTs) |

OR 0.74 (0.49 to 1.14) | 34.1% | 27.7% (20.2 to 37.1) |

6.4% fewer (13.9 fewer to 3 more) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | The risk of disability‐worsening is less with disease‐modifying drugs than with placebo, but there is a lot of uncertainty in the effect | |

|

Relapse Proportion of participants with relapse during 24 months of treatment Participants: N = 618 (1 RCT) |

OR 0.65 (0.38 to 1.12) | 41.6% | 31.7% (21.3 to 44.4) |

10.0% fewer (20.3 fewer to 2.8 more) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | The risk of relapse is less with disease‐modifying drugs than with placebo, but there is a lot of uncertainty in the effects | |

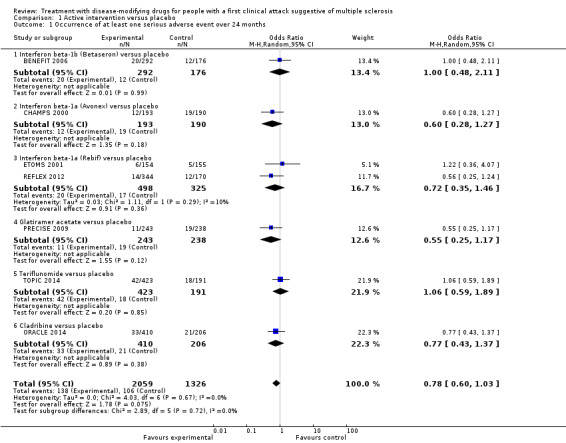

| Occurrence of at least one serious adverse event Proportion of participants with at least one serious adverse event during 24 months of treatment Participants: N = 3385 (7 RCTs) | OR 0.78 (0.60 to 1.03) | 8.0% | 6.3% (5.0 to 8.2) | 1.6% fewer (3 fewer to 0.2 more) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,e | Compared to placebo, disease‐modifying drugs were associated with less risk of serious adverse events | |

|

Withdrawls or drug discontinuation due to adverse events during 24 months of treatment Participants: N = 2693 (5 RCTs) |

OR 2.43 (0.91 to 6.49) | 3.5% | 8.0% (3.2 to 18.9) | 4.6% more (0.3 fewer to 15.4 more) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,f,g | Compared to placebo interferon beta 1‐b, glatiramer acetate, and cladribine were associated with higher risk of withdrawals due to adverse events | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **EDSS: expanded disability status scale CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio |

|||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aHigh risk of bias for blinding of participants and outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data. bSurrogate outcome in both studies contributing to this estimate. cThe confidence interval does not rule out a null effect or benefit. dOnly one study contributed to this estimate. eDefinition and methods of monitoring and detecting serious adverse events not reported in most trials. fHigh heterogeneity (I² = 78%, P = 0.001) not explained; high subgroup differences (I² = 75%, P = 0.003). gDefinition and methods of monitoring and detecting adverse events not reported in most trials.

Summary of findings 2. Is early treatment with disease‐modifying drugs more efficacious and safer than delayed treatment?

| Patient: adults with first attack suggestive of MS Setting: MS centres Intervention: early disease‐modifying drug treatment Comparison: delayed disease‐modifying drug treatment; after the second attack or diagnosis with clinically definitive MS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without early disease‐modifying drug treatment | With early disease‐modifying drug treatment | Difference | ||||

|

Disability‐worsening Proportion of participants with disability‐worsening at a maximum of five years' follow‐up (assessed by EDSS**) Participants: N = 1868 (4 open‐label extension studies) |

OR 0.88 (0.50 to 1.57) | 40.2% | 37.2% (25.2 to 51.4) | 3.0% fewer (15 fewer to 11.1 more) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c, d | No significant effect of early treatment compared to delayed treatment during five years' follow‐up; however there is a significant heterogeneity between the studies |

|

Relapse Proportion of participants with relapse at a maximum of five years' follow‐up Participants: N = 1485 (3 open‐label extension studies) |

OR 0.35 (0.26 to 0.48) | 83.4% | 63.8% (56.7 to 70.7) | 19.6% fewer (26.7 fewer to 12.7 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Early treatment reduced the risk of relapses compared to delayed treatment during five years' follow‐up |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **EDSS: expanded disability status scale CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aHigh risk of bias for allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data. bSurrogate outcome in two out of four studies contributing to this estimate. cHigh heterogeneity (I² = 67%, P = 0.03). dThe confidence interval fails to exclude important benefit or important harms.

Background

Description of the condition

Since the revision of the McDonald criteria in 2010 (Polman 2011), multiple sclerosis (MS) can be diagnosed at the time of a first clinical attack when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows the presence of focal lesions in the white matter of the central nervous system, which are considered typical for MS in terms of distribution, morphology, evolution and signal abnormalities on conventional MRI sequences (Filippi 2016). Opinion leaders have recommended early action as "treating at first clinical attack may be the most effective strategy to manage disease progression" (Freedman 2014). Revised guidelines of the Association of British Neurologists (Scolding 2015) and NHS England (NHS England 2014) suggest that treatment should be advised for patients within 12 months of a first attack, if MRI establishes a diagnosis of MS according to the 2010 McDonald criteria or predicts a high likelihood of recurrent attacks. The benefit of starting early treatment with disease‐modifying drugs has been demonstrated by some short‐term trials that showed delay of a second attack in participants given interferons beta (ETOMS 2001) or glatiramer acetate (PRECISE 2009) compared with those on placebo. On the basis of these results, interferons beta and glatiramer acetate were approved by national regulatory agencies for treating MS at clinical onset (EMA 2015a). However, the available evidence does not indicate that the prevention of recurrent attacks has an effect on disability (CHAMPS 2012 (10 years FU); Frischer 2009), and large variability of long‐term disability‐worsening has been reported, even among people with frequent early relapses (Scalfari 2013). Once the decision for early treatment is made, patients and their healthcare providers need to select one of several disease‐modifying drugs. Most of the evidence about the relative efficacy and safety of interventions is non‐specific to early treatment. In a previously published review, moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence suggested that alemtuzumab, natalizumab and fingolimod were associated with greater benefit for preventing recurrent attacks compared with placebo, and evidence of moderate quality indicated that natalizumab was associated with greater benefit for preventing disability‐worsening among all treatments evaluated (Tramacere 2015). Despite alemtuzumab and natalizumab having been proven to exert higher relapse suppression, because of safety concerns, the guidelines of the Association of British Neurologists recommended their use as second‐line treatment, or as treatment for people with rapidly evolving relapsing‐remitting MS. Beta interferons, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate and fingolimod are recommended as first‐line agents (Scolding 2015). Australian and New Zealand guidelines allow neurologists the discretionary use of all disease‐modifying drugs as first‐line treatments (Broadley 2014).

Description of the intervention

We considered all disease‐modifying drugs that are used, approved or off‐label, or are currently under marketing authorisation or investigation for people with a first clinical attack. We considered that all agents used or under investigation for relapsing‐remitting MS could be given to people with a first attack complying with the 2010 McDonald criteria. More specifically, we are interested in drugs that have been approved for a first attack complying with 2010 McDonald criteria.

Beta interferons (Betaferon/Betaseron®; Extavia®; Rebif®; Avonex®) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) (EMA 2015a; FDA 2012a; FDA 2012b; FDA 2013). These medications are administered subcutaneously, except for beta interferon 1a (Avonex®), which is administered via intramuscular injections. Approved for relapsing‐remitting MS

Natalizumab (Tysabri®) (EMA 2006; FDA 2006) administered by intravenous infusion at a dose of 300 mg every four weeks

Fingolimod (Gilenya®) (EMA 2011; FDA 2010) given at an oral dose of 0.5 mg once daily

Teriflunomide (Aubagio®) (EMA 2013a; FDA 2012) given at an oral dose of 7 mg or 14 mg once daily

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®) (EMA 2014a; FDA 2013) given at an oral dose of 240 mg twice daily

Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®) (EMA 2013b; FDA 2014a) administered intravenously in two annual treatment courses ‐ the first at a dose of 12 mg daily on five consecutive days (60 mg total dose), and the second, 12 months later, on three consecutive days (36 mg total dose)

Daclizumab (Zinbryta®) administered by subcutaneous or intravenous injections and approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (EMA 2016) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (FDA 2016)

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus®) (FDA 2017) administered intravenously at an initial single dose of 300 mg followed two weeks later by a second 300 mg intravenous infusion. Subsequent doses of 600 mg intravenously every six months. Approved for relapsing forms of MS and primary progressive MS

Pegylated interferon beta‐1a (Plegridy®) (EMA 2014b; FDA 2014b) given by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 125 µg every 14 days

Cladribine (Movectro®) approved in Russia and Australia in 2010 (Murphy 2010). EMA (EMA 2015b) and FDA in 2011 did not approve it because of a suspected increase in cancer risk. A meta‐analysis failed to confirm these concerns (Pakpoor 2015)

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone®) approved in 2000 in the USA (FDA 2000), Europe and other countries for relapsing‐remitting and progressive MS. It is administered as a short intravenous infusion every three months. Safety concerns include cardiotoxicity and acute leukaemia

Azathioprine (Imuran®) used in many countries on the basis of placebo‐controlled randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published more than two decades ago. However, since interferons beta were approved, azathioprine is no longer recommended as first‐line therapy (Goodin 2002). It is taken orally, 2 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg per day. Intravenous immunoglobulins are used for people with severe and frequent relapses, for whom other treatments were contraindicated (Scolding 2015)

Rituximab (Rituxan® or Mabthera®) administered intravenously. Currently under marketing authorisation or investigation

Laquinimod (Nerventra®) given at an oral dose of 0.6 mg daily. The drug received a negative opinion from EMA (EMA 2014c). Studies of laquinimod in relapsing‐remitting MS are ongoing (Active Biotech 2014).

How the intervention might work

Immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory effects are common to all treatments included in the review.

Approved interventions

Beta interferons are naturally occurring cytokines that possess antiviral activity and a wide range of anti‐inflammatory properties. Recombinant beta interferons are believed to directly increase expression and concentration of anti‐inflammatory agents, while downregulating expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Kieseier 2011).

Glatiramer acetate exerts an immunomodulatory action by inducing tolerance or anergy of myelin‐reactive lymphocytes (Schmied 2003). Glatiramer acetate may promote neuroprotective repair processes (Aharoni 2014).

Natalizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody directed against the alfa4 integrin. This integrin is essential in the process by which lymphocytes gain access to the brain by allowing cells to penetrate the blood‐brain barrier. Natalizumab binds alfa4β1 and alfa4β7 integrin on the surface of circulating T lymphocytes, preventing interaction with cellular adhesion molecules that facilitate extravasation and migration from the circulation to the central nervous system (CNS) (Millard 2011).

Fingolimod is a sphingosine‐1‐phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator that prevents lymphocyte egress from lymphoid tissues, thereby reducing autoaggressive lymphocyte infiltration into the CNS. S1P receptors are also expressed by many CNS cell types and have been shown to influence cell proliferation, morphology and migration. Fingolimod crosses the blood–brain barrier and therefore may have direct CNS effects (Chun 2010).

Teriflunomide acts as an inhibitor of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), a mitochondrial enzyme involved in pyrimidine synthesis for DNA replication in rapidly proliferating cells. The drug reduces T lymphocyte and B lymphocyte activation and proliferation, and may attenuate the inflammatory response to autoantigens in MS. However, the exact mechanism of action for teriflunomide is not fully understood. Some observations suggest that the drug may have immunological effects outside of its ability to inhibit pyrimidine synthesis in rapidly proliferating cells (Claussen 2012; Oh 2013).

Dimethyl fumarate derives from fumaric acid, promotes anti‐inflammatory activity and can inhibit expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules. Actions of neuroprotective and myelin‐protective mechanisms have been proposed (Linker 2011; Wilms 2010).

Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody to CD52 on the cell surface of lymphocytes and monocytes. Its effects are thought to be mediated by extended B and T lymphocyte depletion followed by a distinctive pattern of T and B cell repopulation that begins within weeks of treatment and leads to a rebalanced immune system, including an increased percentage of regulatory and memory T cells. Effects of alemtuzumab persisted after it was cleared from the circulation (Lycke 2015).

Daclizumab is a monoclonal antibody to the interleukin‐2 receptor CD25 that is expressed on immune cells. The exact mechanism is not well understood. Daclizumab interrupts interleukin‐2‐mediated cell activation, thereby preventing expansion of autoreactive T lymphocytes and inhibiting survival of activated T cells (Wuest 2011).

Ocrelizumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody designed to selectively target CD20‐positive B lymphocytes, a specific type of immune cell thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal nerve cell damage. The drug depletes CD20 B cells, it increases antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity effects and reduces complement‐dependent cytotoxicity effects (Kappos 2011).

Pegylated interferon beta‐1a (PEG‐IFN) is the drug obtained by PEGylation of IFN beta‐1a (Avonex®) (i.e. joining of a polyethylene glycol group (PEG) molecule to the IFN beta‐1a molecule). PEGylation has been applied to increase IFN stability, solubility and half‐life, and to reduce dosing frequency (Hu 2012).

Cladribine is a chemotherapeutic drug approved for treatment of people with hairy‐cell leukaemia, a subtype of chronic lymphoid leukaemia. Short courses of cladribine induce prolonged lymphopenia by selectively interfering with DNA synthesis and repair in T and B lymphocytes lasting months to years (Leist 2011).

Mitoxantrone is a cytotoxic drug that intercalates with DNA and inhibits both DNA and RNA synthesis, thus reducing the number of lymphocytes (Fox 2004).

Interventions used off‐label

Azathioprine is a cytotoxic immunosuppressive drug that acts as a prodrug for mercaptopurine, inhibiting an enzyme required for DNA synthesis. Thus it most strongly affects proliferating cells, such as T cells and B cells of the immune system (Tiede 2003).

Intravenous immunoglobulins may improve remyelination of demyelinated axons through mediation of cytokines. However, their mechanism of action in MS remains unclear (Stangel 1999).

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody to CD20 expressed on pre‐B and mature B cells; it acts by depleting these cells in the circulation and the CNS. Although MS was traditionally considered a T cell‐mediated disease, accumulating evidence suggests that B cells may play a role (Lycke 2015; Naismith 2010).

Interventions currently under marketing authorisation or investigation

Laquinimod may have an immunomodulatory effect on the peripheral and central nervous systems. This drug modulates the function of various myeloid antigen‐presenting cell populations, which then downregulate pro‐inflammatory T cell responses. Furthermore, data indicate that laquinimod acts directly on resident cells within the CNS to reduce demyelination and axonal damage. However, exactly how the drug works remains unknown (Varrin‐Doyer 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Uncertainty

Many treatment options are available, and patients and their clinicians may choose to start with a drug of moderate efficacy and general safety or with a drug of high efficacy and a complex safety profile. Consequently, a comprehensive appreciation of the benefits and risks of all treatment approaches is urgently needed (Scolding 2015; Wingerchuk 2014).

Early treatment

Interferons and glatiramer acetate are indicated by the FDA and the EMA for treatment of people who have experienced a first attack and are at high risk of recurrent attacks. Other immunotherapies have been reported to delay recurrent attacks, although their effect on disability prevention remains unclear. In addition, various national guidelines provide conflicting information about effects of these treatments and their use as first‐line or second‐line therapy (see Description of the condition). This uncertainty results from several factors, including intermediate outcomes and short follow‐up periods in the clinical trials included in published reviews. Immunotherapies administered early in the disease can delay intermediate outcomes (i.e. short‐term relapses), but suppression of early relapses may not necessarily correlate with long‐term disability prevention (Frischer 2009; Scalfari 2013). Therefore an effect on disability cannot be claimed solely on the basis of relapse prevention (EMA 2015a). Given that most evidence has been derived from short‐term trials with low power to investigate rare adverse events, safety outcomes have not been extensively investigated. Consequently, a demonstration and quantification of the benefit and safety of the early treatment versus delayed treatment is still required.

Choice of interventions for early treatment

Patients and their doctors must be given information about the relative benefit and safety of the various treatment options if they are to make informed decisions. Various disease‐modifying drugs have been shown to have different benefit/acceptability profiles. Differences in benefit are as important to consider as differences in safety. For example, local injection site reactions and flu‐like symptoms have emerged as the main adverse effects of interferons beta, and cardiotoxicity and acute leukaemia as major safety issues for mitoxantrone. Investigators have described fatal cases of progressive multi‐focal leucoencephalopathy in people treated with natalizumab (EMA 2006), fingolimod (EMA 2011) and dimethyl fumarate (EMA 2014a). To support informed decision‐making, there is a need to identify, systematically collect and synthesise information about relative safety and efficacy between interventions administered to people with the first attack suggestive of MS.

Relevance

In July 2014, Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis launched a ‘Priority Setting Survey’ and invited consumers and MS societies to answer a questionnaire identifying priority research questions considered to have the most relevant impact for all stakeholders. The question ‐ "Early onset of treatment may avoid disease progression?" ‐ was one of the most frequently reported by people with MS and family members. The question ‐ "Does early treatment with aggressive disease‐modifying drugs improve the prognosis for people with MS?" ‐ addresses one of the top 10 MS priorities reported by the James Lind Alliance in collaboration with the UK MS Society 2012. This review aims to answer these two questions by comparing all disease‐modifying drugs with placebo; it also plans to provide an assessment of the relative effects of each drug compared with one other and a ranking of treatments according to benefit and safety. The significance of this project is underlined by the fact that evaluation of disease‐modifying drugs for people with a first clinical attack has been identified as a priority and is featured in the Cochrane Priority Review List 2015/16.

Most published reviews have compared a single treatment versus placebo and have made inferences about benefits and safety. This information is unlikely to be useful in practice, as people with MS have several treatment options. Network meta‐analysis (NMA), which is an extension of the traditional pairwise meta‐analysis, collates information from studies comparing different treatments in order to form a ‘network of interventions’. This provides information about the relative effects of all interventions included in the network, even those not directly compared in any trial and a hierarchy of treatments ordered by efficacy and safety. None of the existing comparative effectiveness reviews have specifically addressed disease‐modifying drugs in early treatment. As the number of people who choose to start treatment soon after diagnosis increases, it is important for healthcare providers to know the relative benefit and safety of the various treatment options in this particular setting.

Another important limitation of existing reviews is that all include randomised controlled trials. Although this study design is theoretically associated with low risk of bias, it has several shortcomings. First, randomised trials do not provide patient follow‐up for a long period; consequently, this design is not appropriate when rare safety outcomes are of interest. Second, randomised trials are typically undertaken in highly selected conditions and do not represent real‐world settings. Consequently, the generalisability of findings is doubtful. For these reasons, interest in including non‐randomised studies in the decision‐making process is growing (Faria 2015), and innovative methods have been developed for combining data obtained through different study designs (Schmitz 2013; Verde 2015).

Overall, we believe that despite the wealth of information and the plethora of studies and reviews on treatments for MS, uncertainty surrounds the relative ranking of disease‐modifying drugs when treatment starts early. In particular, the issue of safety is less well studied, as evidence from non‐randomised studies that provide useful information on adverse events has not been systematically considered. We believe that having access to high‐quality health information is an essential component of good decision‐making processes and helps people take control of their health. Our certainty comes from the results of studies previously undertaken by Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis, wherein people with MS and their family members told us that they want access to high‐quality information about MS provided by sources they can trust (Colombo 2014; Colombo 2016; Hill 2012; Synnot 2014).

Potential to change or influence clinical practice or health policy

The review aimed to provide critical information necessary in making informed healthcare decisions on treatments for people with MS, their neurologists and family members. Notably, marked variability in treatment decisions has been reported, likely as the result of physician preference and opinion (Palace 2013). Disease‐modifying drugs are expensive and their use has significant economic implications for the healthcare system. These treatments are associated with high risk of adverse events, which indirectly further increases treatment costs. Identifying treatment that offers a better benefit and safety profile, with particular attention to safety, may help to reduce costs.

Objectives

The review aimed to answer three research questions:

is early treatment efficacious and safe compared to placebo or no treatment?

are there differences in efficacy and safety between the various drugs administered for early treatment?

is early treatment better than delayed treatment?

Consequently, the objectives were:

to estimate the benefit and safety of disease‐modifying drugs that have been evaluated in all studies (randomised or non‐randomised) for the treatment of a first clinical attack suggestive of MS compared either with placebo or no treatment;

to assess the relative efficacy and safety of disease‐modifying drugs according to their benefit and safety;

to estimate the benefit and safety of disease‐modifying drugs that have been evaluated in all studies (randomised or non‐randomised) for treatment started after a first attack ('early treatment') compared with treatment started after a second attack or at another later time point ('delayed treatment').

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs, open‐label extension (OLE) studies, controlled clinical trials, cohort studies and registries. Inclusion of non‐randomised controlled studies was supported by the aim to provide additional evidence about long‐term outcomes (in particular safety outcomes) and populations that are typical of real world practice.

An OLE study follows on from a RCT. At the end of the RCT or after the occurrence of a primary outcome event (e.g. conversion to MS), participants receiving placebo were offered the option to switch to the active treatment during an ‘open‐label’ follow‐up. In these studies efficacy and safety were evaluated comparing the early‐treatment group with the delayed‐treatment group.

We included studies with follow‐up of at least one year. We excluded non‐comparative studies.

Types of participants

Adults (aged 18 years or older) with a first clinical attack suggestive of MS as defined in the original articles. We included participants with optic neuritis, isolated brainstem or cerebellar syndrome or spinal cord or other clinical syndrome as a first attack and monofocal or multi‐focal first attacks.

Types of interventions

The following interventions administered as monotherapy were eligible for inclusion: alemtuzumab, azathioprine, cladribine, daclizumab, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, glatiramer acetate, immunoglobulins, interferon beta‐1b (Betaseron®), subcutaneous interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®), intramuscular interferon beta‐1a (Avonex®), laquinimod, mitoxantrone, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, pegylated interferon beta‐1a, rituximab and teriflunomide. We included regimens irrespective of their dose and assumed that treatments are 'jointly randomisable' across trial participants (Salanti 2012). To address the first two review questions we included studies comparing disease‐modifying drugs with placebo, no treatment or another active treatment. To address the third question we included studies comparing early treatment versus delayed treatment with disease‐modifying drugs. We excluded combination treatments, non‐pharmacological treatments, and interventions consisting of over‐the‐counter drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary efficacy outcomes

Disability‐worsening

We measured this as the proportion of participants who experienced disability‐worsening (as defined by the study authors) at 24 months, 36 months or at the end of the study. Most investigators used the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) (Kurtzke 1983). EDSS is based on the results of a neurological examination and the patient’s ability to walk. Scores range from 0 (no neurological abnormality) to 10 (death from multiple sclerosis). Disability‐worsening is often defined as a sustained (3 months or 6 months) increase of at least one point in EDSS recorded over a relapse‐free period.

Relapses

We measured this as the proportion of participants who experienced new relapses over 12 months, 24 months and 36 months or at the end of the study. A relapse is defined as a newly developed or recently worsened symptom of neurological dysfunction that lasted more than 24 hours with or without objective confirmation and that stabilised or resolved either partly or completely.

Primary safety outcomes

Occurrence of at least one serious adverse event

We measured this as the proportion of participants with at least one serious adverse event during the study.

Withdrawing from the study or discontinuing the drug due to adverse events

We measured this as the proportion of participants who withdrew from the study or discontinued the drug due to adverse events during the study.

Secondary outcomes

Time to conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS)

As defined by Poser diagnostic criteria (Poser 1983).

Withdrawing from the study or discontinuing the drug for any reason

We measured this as the proportion of participants who discontinued treatment and were followed‐up to the end of the study or who were lost to follow‐up for any reason.

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not apply any language restrictions to the search.

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the CNS Trials Register , which, among other sources, contains trials from:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, issue 12);

MEDLINE (PubMed) (1966 to 31 December 2016);

Embase (Embase.com) (1974 to 31 December 2016);

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost) (1981 to 31 December 2016);

Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database (LILACS) (Bireme) (1982 to 31 December 2016);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); and

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

Information on the Trials Register or the Review Group and details of the search strategies used to identify trials can be found in the 'Specialised Register' section within the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the CNS module. We described in Appendix 1 the keywords that we used to search for trials. We performed an expanded search to identify articles of non‐randomised studies in MEDLINE (Appendix 2) and Embase (Appendix 3).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of all retrieved articles, texts and other reviews on the topic.

We contacted study authors and researchers active in this field to ask for additional data, if necessary.

We searched for FDA and EMA reports.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two teams of three authors each (MC, MM and AS; OB, FP and GF) independently assessed titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies for inclusion. We obtained the full text of the study when necessary to confirm inclusion. All completed RCTs, OLEs, CCTs, and cohort studies were included if the studies contained clinically relevant benefit and safety outcomes for any of the drugs included in the review and met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the articles were screened to identify any studies missed by the electronic database search. Discrepancies in judgement were resolved by discussion between review authors.

Data extraction and management

The six review authors extracted data independently and in duplicate using an Excel sheet piloted on three articles. We resolved disagreements on extractions by discussion.

Outcome data

For all dichotomous outcomes, we extracted arm‐level data (number of participants with events and number of participants). For time to conversion to CDMS we extracted hazard ratios (HR) and relative standard errors. When timing of outcome measure was not reported at selected time points, we extracted data as close as possible to that time point. When outcome data were not reported or were unclear in the original article we checked reports from the FDA or EMA. If necessary, we sought additional information from the trial investigators. For non‐randomised and OLE studies, we preferred adjusted relative treatment effects to unadjusted.

Other extracted data

Study design: year of publication, monocentric or multicentric, recruitment period, time between onset of first attack and randomisation method;

Participants: age, gender, monofocal or multi‐focal onset presentation, type of first attack, baseline EDSS, baseline MRI lesions, proportion of participants treated with steroids at the first attack;

Definitions of relapse and disability‐worsening;

Interventions: route, dose, frequency or duration of treatment/follow‐up.

In OLE studies we also extracted the number of participating centres, and the number of participants who entered and completed the study during different follow‐up times. For each non‐randomised study, we recorded the analysis method used to reduce confounding.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

RCTs and OLEs

We assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the Cochrane recommendations for assessment (Higgins 2011). These included: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel and participants, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and evidence of major baseline imbalance. We explicitly judged the risk of bias on each criterion as 'low', 'high' or 'unclear'. We judged attrition as having low risk of bias when numbers and causes of dropouts were balanced between arms. To summarise the quality of evidence we considered allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors and incomplete outcome data to classify each study as having low risk of bias (when all three criteria were judged at low risk of bias), high risk of bias (when at least one criterion was at high risk of bias), unclear risk of bias when all three criteria were judged as having unclear risk of bias, and moderate risk of bias in the remaining cases.

Participants in OLE studies were informed at the time they were recruited into the RCT that they could be enrolled into an OLE study. Then the participants taking placebo had the possibility to switch to the active treatment when they were diagnosed with CDMS or after they completed the RCT. The participant allocated to the active treatment could decide to enter the OLE study at the end of the RCT and continue taking the treatment. The consequences of the OLE design were that original allocation concealment was lost, participants entering the extension were clearly selected, for example, those who had treatment benefit and did not discontinue treatment due to adverse events. Moreover, participants and outcome assessors were not blinded in the OLE phases. For these reasons, we considered OLE studies at high risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants and outcome assessors. We reported the 'Risk of bias' assessments for RTC and OLE studies separately.

Cohort studies

We assessed the risk of bias in the cohort studies using the ROBINS‐I tool for NRS (Sterne 2016) that includes the following bias domains: confounding, selection of participants into the study, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes and selection of reported result. We judged each domain as pertaining to low, moderate, serious, critical risk of bias or no information about risk of bias and performed an overall 'Risk of bias' assessment for each study according to the criteria reported in the ROBINS‐I tool for NRS (Sterne 2016).

Adverse events

We evaluated the methods of monitoring and detecting adverse events in each included study answering to the following two questions: firstly, did researchers actively monitor for adverse events, or did they simply provide spontaneous reporting of adverse events that arose; and secondly, did study authors define serious adverse events according to an accepted international classification and report the number of serious adverse events? (Singh 2011). We have reported answers to these questions in a table 'Assessment of adverse events monitoring, definition and reporting of serious adverse events'. We used the resulting answers to decide indirectness in GRADE.

MC, MM and AS independently assessed the risk of bias of each RCT and OLE study and resolved disagreements by discussion. OB, FP and GF independently assessed risk of bias of the cohort studies and resolved disagreements by discussion. The final judgments were established by GF and CDG.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated, through pairwise meta‐analysis, treatment effects of competing interventions by using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each binary outcome at each time point and HR with 95% CIs for conversion to CDMS. We estimated the absolute effects for primary outcomes included in the 'Summary of fIndings' table. We presented the results from NMA of RCTs as summary relative effect sizes according to the type of outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

For multi‐arm trials, intervention groups are all those that can be included in a pairwise comparison of intervention groups, which, if investigated alone, would meet the inclusion criteria. For example, if a study compares 'interferon beta versus natalizumab versus interferon beta plus natalizumab' only one comparison ('interferon beta vs natalizumab') addresses the review objectives. We merged data from study arms involving the same drug at different doses. For outcomes for which data were available as treatment effects (i.e. HR), we used the data from the arm trial at highest dose.

Dealing with missing data

We considered missing outcome data in the 'Risk of bias' assessment. In some of the studies included in the review, missing outcome rates were considerable and we accounted for the their impact on the outcomes assuming that they were not missing at random. We assumed a relationship between the unknown outcome among missing participants and the known outcome among observed participants by using the 'informative missingness odds ratios' (IMORs) approach, allowing for uncertainty in the missing data imputations (Higgins 2008; White 2008). We assumed in both groups that the odds of relapses or disability‐worsening in missing participants were roughly 6 times times the odds in the observed participants with 95% CI from 3 to 7 (IMOR = 5.95, 95% CI 3 to 7). We set these values after discussion with clinicians, who suggested that missing outcomes are most probably unfavourable outcomes. To implement the approach we used the 'metamiss' command in Stata v14 (available from https://www.mrc‐bsu.cam.ac.uk/software/stata‐software/).

Assessment of heterogeneity

In standard pairwise meta‐analyses, we estimated different heterogeneity variances for each pairwise comparison. In NMA, we assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance for all comparisons. We assessed the presence of statistical heterogeneity within each pairwise comparison by visual inspection of the forest plots and by calculating the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). The type of drug used in the various studies was a suspected source of heterogeneity and we performed all pairwise meta‐analyses in subgroups, considering the P value from the subgroup analyses as an indication of differences between interventions.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were not able to assess the possibility of reporting bias as the number of studies were fewer than 10 in all the analyses.

Data synthesis

We performed pairwise meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model (using the Mantel‐Haenszel estimator for Q) for any treatment versus placebo and for early versus delayed treatment. We performed NMA using a random‐effects model for outcomes evaluated in RCTs over 24 months of follow‐up. The validity of network estimates in NMA is based on the assumption of transitivity (Salanti 2012). We had planned to assess whether the distribution of potential effect modifiers (among those reported extracted data in Data extraction and management) were balanced across comparisons (Jansen 2013), however, none of the networks that we identified presented enough data to evaluate the assumptions. We conducted pairwise meta‐analyses in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software (RevMan 2017) and NMA in Stata v14 using the network and network_graphs packages in Stata v14 (available from https://www.mrc‐bsu.cam.ac.uk/software/stata‐software/).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used the test for subgroup differences to assess the statistical heterogeneity across comparisons with different active agents within standard pairwise meta‐analyses. In the context of NMA, we did not have enough information to assess incoherence, defined as the statistical disagreements between direct and indirect effect sizes, as only indirect evidence was available.

Sensitivity analysis

We re‐ran the analyses of excluding observational studies when relevant.

'Summary of findings' table

We have presented the main results of the review in two 'Summary of findings' tables, according to recommendations provided in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0) (Schunemann 2011). We judged the credibility of the evidence from pairwise meta‐analysis in accordance with the methods of the GRADE Working Group (GRADE Working Group 2004). For each outcome the assumed risk in the control group was based on the proportion of events in the included studies.

In the first 'Summary of findings' table we included an overall grading of the evidence for four patient‐important outcomes with regards to the review question 'Are disease‐modifying drugs for a first attack suggestive of MS effective and safe compared to placebo?'

Disability‐worsening during 24 months of treatment

Relapse during 24 months of treatment

Occurrence of at least one serious adverse event during 24 months of treatment

Withdrawing from the study or discontinuing the drug due to adverse events during 24 months of treatment

In the second 'Summary of findings' table we included an overall grading of the evidence for two patient‐important outcomes with regards to the review question 'Is early treatment with disease‐modifying drugs more efficacious and safe than delayed treatment?'

Disability‐worsening at a maximum of five years' follow‐up from randomisation

Relapse at a maximum of five years' follow‐up from randomisation

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

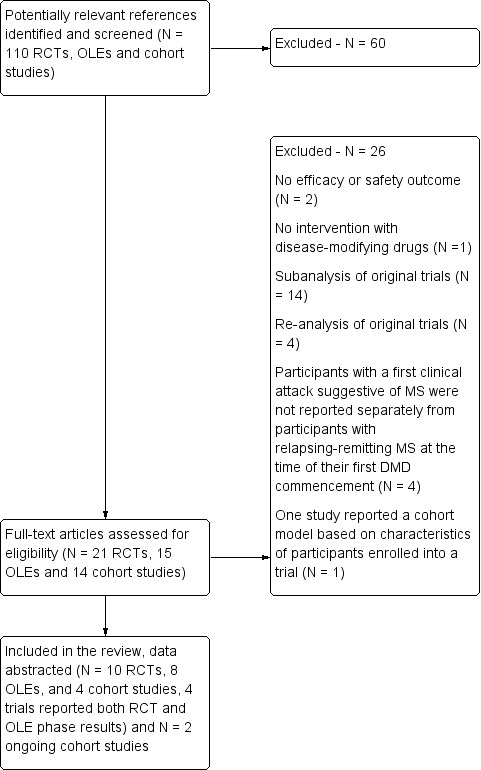

A flow diagram describes the results of the electronic search (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram. DMD: disease‐modifying drugs; OLEs: open label extension studies; RCTs: randomised controlled trials

Included studies

Characteristics of included studies and Table 3 provide details on the characteristics of the included studies. We included 10 RCTs involving 3745 participants and published between 2000 and 2014 (Achiron 2004; BENEFIT 2006; CHAMPS 2000; ETOMS 2001; Motamed 2007; ORACLE 2014; Pakdaman 2007; PRECISE 2009; REFLEX 2012; TOPIC 2014); eight OLEs involving 1868 participants and published between 2006 and 2016 (BENEFIT 2007 (3 years FU); BENEFIT 2009 (5 years FU); BENEFIT 2014 (8.7 years FU); BENEFIT 2016 (11 years FU); CHAMPS 2006 (5 years FU); CHAMPS 2012 (10 years FU); PRECISE 2013 (5 years FU); REFLEX 2016 (3 and 5 years FU)); and four cohort studies involving 4775 participants and published between 2010 and 2016 (ACISS 2010; GERONIMUS 2013; MSBASIS 2016; Tintore 2015).

1. Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Type of intervention | Route |

RCTs N = 10 |

OLEs N = 8 |

Cohort studies N = 4 |

| Interferon beta‐1b sc (Betaseron®) | sc | 1 | 4 OLEs at a maximum follow‐up of 3, 5, 8.7, and 11 years | 0 |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Avonex®) | im | 2 | 2 OLEs at a maximum follow‐up of 5 and 10 years | 0 |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®) | sc | 3 | 1 OLE at a maximum follow‐up of 3 and 5 years | 0 |

| Glatiramer acetate sc | sc | 1 | 1 OLE at a maximum follow‐up of 5 years | 0 |

| Cladribine os | os | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Teriflunomide os | os | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Immunoglobulins iv | iv | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| disease‐modifying drugs | ‐ | 0 | 0 | follow‐up from 2 to 6 years |

im: intramuscular; iv: intravenously; OLEs: open‐label extension studies; os: oral; RCTs: randomised controlled studies; sc: subcutaneous

All RCTs were placebo‐controlled studies with a median of two years follow‐up. Six (60%) of the 10 included RCTs assessed interferons in people with a first attack suggestive of MS. BENEFIT 2006 provided data of four OLEs at maximum follow‐up of three, five, eight and 11 years from randomisation (BENEFIT 2007 (3 years FU); BENEFIT 2009 (5 years FU); BENEFIT 2014 (8.7 years FU); BENEFIT 2016 (11 years FU)); CHAMPS 2000 provided data of two OLEs with a maximum follow‐up of five and 10 years (CHAMPS 2006 (5 years FU); CHAMPS 2012 (10 years FU)); PRECISE 2009 provided data of one OLE with a maximum follow‐up of five years (PRECISE 2013 (5 years FU)); and REFLEX 2012 provided data of two OLEs with at maximum follow‐up of three and five years (REFLEX 2016 (3 and 5 years FU)). Follow‐up of the cohort studies ranged from two to six years.

We identified two ongoing cohort studies (NCT01371071; NCT01013350). We will include these studies in a future update of this review. Characteristics of ongoing studies provides details on the characteristics of the two studies.

Excluded studies

After full‐text review we excluded 26 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies): 14 studies reported sub‐analysis of original trials (BENEFIT 2007; BENEFIT 2008; BENEFIT 2011; BENEFIT 2012; BENEFIT 2014a; CHAMPS 2001; CHAMPS 2002a; CHAMPS 2002b; CHAMPS 2002c; CHAMPS 2003; ETOMS 2003; Filippi 2004; REFLEX 2014a; REFLEX 2014b) and four studies reported re‐analysis of original trials (BENEFIT 2014b; CHAMPIONS 2015; CHAMPS 2009; Moraal 2009); in four studies participants with a first clinical attack suggestive of MS were not reported separately from participants with relapsing‐remitting MS at the time of their first disease‐modifying drugs commencement (Meyniel 2012; Mowry 2009; MSBASIS 2015; SWISS COHORT STUDY 2013); two studies did not include efficacy or safety outcome (Curkendall 2011; SWISS COHORT STUDY 2016); one cohort study did not evaluate disease‐modifying drugs (Kuhle 2015); and one study reported a cohort model based on characteristics of participants enrolled into the BENEFIT trial (Lazzaro 2009).

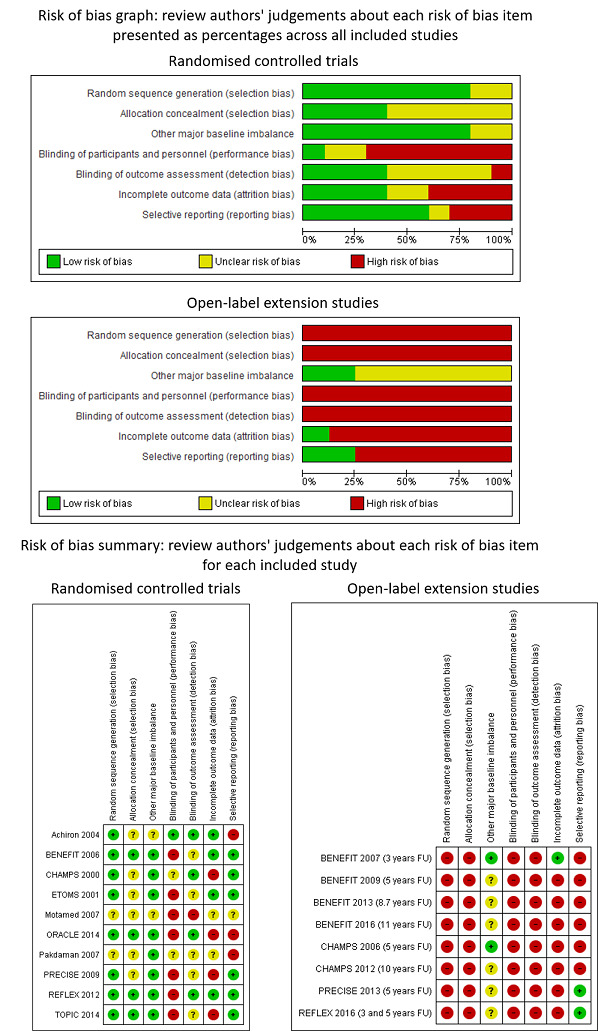

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessments are summarised separately for RCTs and OLEs in Figure 2. Details on the judgement for each RCT and OLE study and the reason for that judgement are reported in Characteristics of included studies. Risk of bias in the included cohort studies was assessed by ROBINS‐I and it is reported in Table 4.

2.

Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies and review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

2. Risk of bias in included cohort studies (ROBINS‐I).

| ACISS 2010 | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgement |

| Confounding | Serious | All known important domains were not appropriately controlled for |

| Selection of participants into the study | Low | All participants who would have been eligible for the target trial were likely included in the study and for each participant start of follow up and start of intervention likely coincided |

| Classification of interventions | Low | Intervention status was well defined and intervention definition was based on information collected at the time of intervention |

| Deviations from intended interventions | NI | No information was reported on whether there was deviation from the intended intervention |

| Missing data | Critical | There were critical differences between early, delayed or no treatment in participants with missing data and an appropriate analysis to address missing data was not done |

| Measurement of outcomes | Serious | The outcome measures were subjective and assessed by assessors aware of the intervention received by study participants. This judgment is applicable to all the three outcomes reported in the article |

| Selection of the reported result | Low | There was evidence that reported results corresponded to all intended outcomes and analyses |

| Overall bias | Critical | Study judged to be at critical risk of bias in one domain |

| GERONIMUS 2013 | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgement |

| Confounding | Moderate | Confounding expected, all known important confounding domains appropriately measured and controlled for, and reliability and validity of measurement of important domains were sufficient, such that we do not expect serious residual confounding |

| Selection of participants into the study | Low | All participants who would have been eligible for the target trial were likely included in the study and for each participant start of follow up and start of intervention likely coincided |

| Classification of interventions | Serious | Intervention status was not well defined |

| Deviations from intended interventions | NI | No information was reported on whether there was deviation from the intended intervention |

| Missing data | Low | Data were reasonably complete |

| Measurement of outcomes | Serious | CDMS was assessed by assessors aware of the intervention received by study participants |

| Selection of the reported result | Low | There was evidence that reported results corresponded to all intended outcomes and analyses |

| Overall bias | Serious | Study judged to be at serious risk of bias in two domains, but not at critical risk of bias in any domain |

| MSBASIS 2016 | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgement |

| Confounding | Serious | Important domains were not appropriately controlled for |

| Selection of participants into the study | Critical | Selection into the study was very strongly related to intervention and outcome and this could not be adjusted for in analyses |

| Classification of interventions | Serious | Intervention status was not well defined |

| Deviations from intended interventions | NI | No information was reported on whether there was deviation from the intended intervention |

| Missing data | NI | No information was reported on missing data |

| Measurement of outcomes | Serious | The outcome measures were subjective and they were assessed by assessors aware of the intervention received by study participants. Follow‐up duration not reported |

| Selection of the reported result | Low | There was evidence that reported results corresponded to all intended outcomes and analyses |

| Overall bias | Critical | Study judged to be at critical risk of bias in one domain |

| Tintore 2015 | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgment | Support for judgement |

| Confounding | Serious | Important domains were not appropriately controlled for |

| Selection of participants into the study | Low | All participants who would have been eligible for the target trial were likely included in the study and for each participant start of follow up and start of intervention likely coincided |

| Classification of interventions | Serious | Intervention status was not well defined |

| Deviations from intended interventions | NI | No information was reported on whether there was deviation from the intended intervention |

| Missing data | Serious | Reasons for missing data differed substantially across interventions, and the analysis is unlikely to have removed the risk of bias arising from the missing data |

| Measurement of outcomes | Serious | The outcome measures were subjective and assessed by assessors aware of the intervention received by study participants. This judgment is applicable to all outcomes reported in the article |

| Selection of the reported result | Low | There was evidence that reported results corresponded to all intended outcomes and analyses |

| Overall bias | Serious | Study judged to be at serious risk of bias in four domains, but not at critical risk of bias in any domain |

ROBINS‐I is a tool to evaluate Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomised Studies ‐ of Interventions (Sterne 2016)

RCTs

Random sequence generation

Eight out of 10 RCTs (80%) reported adequate methods for allocation sequence and we judged them to be at low risk of bias. Two RCTs (20%) did not provide enough information to assess allocation sequence and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies.

Allocation concealment

Four out of 10 RCTs (40%) reported adequate methods for allocation concealment and we judged them to be at low risk of bias. Six RCTs (60%), did not provide enough information to assess allocation concealment and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies.

Other major baseline imbalance

Eight out of 10 RCTs (80%) were adequate in terms of baseline balance and we judged them to be at low risk of bias. Two RCTs (20%) did not provide enough information to assess the presence of other baseline imbalance and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Only one RCT (10%) reported adequate methods for blinding participants and personnel to treatment allocation. Two RCTs (20%) did not provide enough information and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies. We judged seven RCTs (70%) to be at high risk of bias (BENEFIT 2006; ETOMS 2001; Motamed 2007; ORACLE 2014; PRECISE 2009; REFLEX 2012; TOPIC 2014).

Blinding of outcome assessors

Four out of 10 RCTs (40%) reported adequate methods for blinding outcome assessors to treatment allocation. Five RCTs (50%) did not provide enough information and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies. We judged one open‐label study to be at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors (Motamed 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged four out of 10 RCTs (40%) to be at low risk of bias because missing outcome data were balanced in numbers across intervention groups with similar reasons for missing data across groups. Two (20%) studies (Motamed 2007; Pakdaman 2007) reported insufficient information so that it was uncertain whether or not the handling of incomplete data was appropriate. We judged risk of bias for these two trials to be unclear. We judged four trials (40%) to be at a high risk of bias, of which three (CHAMPS 2000; ORACLE 2014; PRECISE 2009) were stopped before the scheduled period of follow‐up because the studies had ended prematurely and a low percentage of participants completed the studies. The fourth study (TOPIC 2014) showed more than 40% of participants lost to follow‐up.

Selective outcome reporting

We judged the majority of included studies (six of 10; 60%) to be at low risk of bias. The study protocols were available or the published reports included those outcomes that had been pre‐specified in the methods section of primary articles. One study did not provide enough information to assess this item and the risk of bias was judged to be unclear. In three trials (30%), we judged risk of bias to be high (Achiron 2004; ORACLE 2014; Pakdaman 2007).

Method of adverse event monitoring

Five included trials (5 out of 10; 50%) reported that adverse events were actively monitored. Four trials (40%) reported insufficient information about the method of adverse events monitoring so that it was uncertain whether or not adverse events were monitored appropriately. CHAMPS 2000 reported adverse events only during the first six months of treatment (Table 5).

3. Assessment of adverse events monitoring, definition and reporting of serious adverse events.

| Study | Did the researchers actively monitor for adverse events or did they simply provide spontaneous reporting of adverse events that arose? | Did the authors define serious adverse events according to an accepted international classification and report the number of serious adverse events? |

| Achiron 2004 | No information | No information |

| ACISS 2010 | No information | No information |

| BENEFIT 2006 | Yes, active monitoring.“Regular visits were scheduled for safety assessments at months 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24”. (page 1243) | No information |

| BENEFIT 2007 (3 years FU) | No information | No information |

| BENEFIT 2009 (5 years FU) | No information | No information |

| BENEFIT 2014 (8.7 years FU) | No information | No information |

| BENEFIT 2016 (11 years FU) | No information | No information |

| CHAMPS 2000 | No active monitoring. "Each center was instructed to report all adverse events during the first six months of treatment, but thereafter to report only serious adverse events". (page 899) | No information |

| CHAMPS 2006 (5 years FU) | No information | No information |

| CHAMPS 2012 (10 years FU) | No information | No information |

| ETOMS 2001 | Yes, active monitoring. "Safety was assessed at 1, 6, 12, 18, 24 months". (page 1577) | Yes to both questions. "Serious adverse events were defined according to the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation". (page 1580) |

| GERONIMUS 2013 | No information | No information |

| Motamed 2007 | Yes, active monitoring."Safety assessments were performed at the end of months 1, 2, 3, 9, 15, and 21 by a neurologist". (page 345) | No information |

| MSBASIS 2016 | No information | No information |

| ORACLE 2014 | Yes, active monitoring. "Adverse events and laboratory findings were recorded at study visits and at regularly scheduled interim visits" (page 259). "International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use". (page 258) | Yes to both questions. "International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use". (page 258) |

| Pakdaman 2007 | No information | No information |

| PRECISE 2009 | Unclear whether the researchers actively monitored for adverse events or they simply provided spontaneous reporting of adverse events | No information |

| PRECISE 2013 (5 years FU) | Unclear whether the researchers actively monitored for adverse events or they simply provided spontaneous reporting of adverse events | No information |

| REFLEX 2012 | Yes, active monitoring. "Active monitoring by personnel was ensured via various testing". (page 34). "Adverse events were coded with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) and analysed according to the preferred terms". (page 35) | Yes to both questions."Adverse events were coded with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) and analysed according to the preferred terms". (page 35) |

| REFLEX 2016 (3 and 5 years FU) | Unclear. "Adverse events (adverse events) were monitored at months 25 and 27 and then every 3 months to the study end". (page 2) | No information |

| Tintore 2015 | No information | No information |

| TOPIC 2014 | Unclear. "Adverse events were reported by study participants or investigators throughout the study; investigators recorded all such events on case report forms". (page 979) | No information |

Serious adverse event definitions

The majority of included studies (7 out of 10; 70%) gave insufficient information on serious adverse events definition, the remaining three trials (30%) provided this definition (Table 5).

OLEs

Random sequence generation

We judged all eight OLEs to be at high risk of bias for sequence generation because there was no random assignment to the open‐label treatment groups.

Allocation concealment

We judged all eight OLEs to be at high risk of bias because there was no allocation concealment with respect to assignment to the open‐label treatment groups.

Other major baseline imbalance

Two out of eight OLEs (25%) were adequate in terms of baseline balance and we judged them to be at low risk of bias. Six OLEs (75%) did not provide enough information to assess the presence of other baseline imbalance and we judged the risk of bias to be unclear for these studies.

Blinding of participants and personnel

None of the eight OLEs blinded participants or personnel to treatment allocation. We judged these studies to be at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessors

None of the eight OLEs blinded outcome assessors to treatment allocation. We judged these studies to be at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

Seven (87%) of the eight OLEs were likely to be at high risk of attrition bias as participants who dropped out ranged from 23% to 70% and proportions and reasons of missing participants differed substantially across intervention groups. Most of the participants who were lost to follow‐up may have not responded in the original RCT or have had adverse events that were not included in the analyses, which could overestimate the treatment benefit or underestimate the adverse effect estimates. In one OLE (BENEFIT 2007 (3 years FU)) the majority of participants (about 80%) contributed outcome data and thus we judged this study to be at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective outcome reporting

We judged most of the included studies (six of eight; 75%) to be at high risk of selective reporting bias. We did not find study protocols in the ClinicalTrials.gov database or in the FDA or EMA databases, and judged published reports to be at high risk of this type of reporting bias if they did not report all expected outcomes, including treatment discontinuation due to adverse events or serious adverse events, that were primary outcomes pre‐specified in the methods section. The six OLEs were likely to be at high risk of selective reporting bias because these studies did not specify in the methods that they intended to report adverse events and treatment discontinuation due to adverse events or serious adverse events were not reported.

Method of adverse event monitoring

All the included OLEs reported insufficient information to judge if adverse events were monitored appropriately or not (Table 5).

Serious adverse event definitions

All the included OLEs did not clearly define ‘serious adverse events’ (Table 5).

Cohort studies

We assessed risk of bias according to ROBINS‐I tool for non‐randomised studies of interventions (Sterne 2016). We judged two (ACISS 2010; MSBASIS 2016) of the four included cohort studies at critical risk of bias, and the other two studies (GERONIMUS 2013; Tintore 2015) at serious risk of bias (Table 4). None of the cohort studies reported the method they used to monitor and detect adverse events or to define serious adverse events (Table 5).

Effects of interventions

Research question 1: is early treatment efficacious and safe compared to placebo or no treatment?

Ten RCTs and two cohort studies compared early intervention versus placebo or no treatment.

Their results are synthesised and presented in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

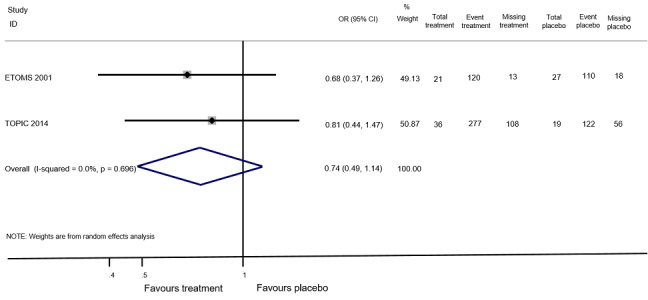

Disability‐worsening

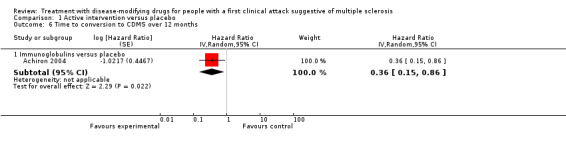

The number of participants who had disability‐worsening during 24 months was available from two RCTs (ETOMS 2001, TOPIC 2014) and 927 participants (25% of those included in the 10 RCTs). The summary OR, which takes into account the missing outcome data, suggested a non‐significant reduction of the odds of disability‐worsening in early treatment with interferon beta‐1a (Rebif®) (ETOMS 2001) or teriflunomide (TOPIC 2014) compared with placebo (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.14, P = 0.696) with very little heterogeneity (I² = 0%) (Figure 3). In one cohort study (ACISS 2010) participants treated with disease‐modifying drugs at their first attack had greater mean score of EDSS measured at 24 months than participants who were never treated (Table 6).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: treatment with disease‐modifying drugs compared with placebo. Random‐effects meta‐analysis results of proportion of participants with disability‐worsening over 24 months in RCT studies. We assumed in both groups that the odds of disability‐worsening in missing participants were 5.95 times the odds in the observed participants with 95% CI from 3 to 7

4. Outcome data from cohort studies.

| ACISS 2010 | Early DMDs treatment (N = 49) | Delayed DMDs treatment (N = 57) |

No treatment (N = 52) |

|

EDSS score over 24 months' follow‐up Mean (SD) Median (range) Kruskal–Wallis H‐Test P value <0.001 |

1.2 (0.9) 1.5 (0‐3) |

1.6 (1.2) 1.5 (0‐6) |

0.8 (0.8) 1.0 (0‐3) |

| P value versus no treatment | 0.016 | < 0.001 | NA |

| P value early versus delayed treatment (Wilcoxon matched pair test) | 0.055 | NA | NA |

|