Abstract

Background

Topiramate is a newer broad‐spectrum antiepileptic drug (AED). Some studies have shown the benefits of topiramate monotherapy in the treatment of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). However, there are no current systematic reviews to determine the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate monotherapy in people with JME. This is an updated version of the original Cochrane Review published in Issue 12, 2015.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate monotherapy in the treatment of JME.

Search methods

For the latest update, on 21 February 2017 we searched Cochrane Epilepsy's Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also searched ongoing trials registers, reference lists and relevant conference proceedings, and contacted study authors and pharmaceutical companies.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating topiramate monotherapy versus placebo or other AED treatment for people with JME, with the outcomes of proportion of responders or experiencing adverse events (AEs).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records, selected studies for inclusion, extracted data, cross‐checked the data for accuracy and assessed the methodological quality. We performed no meta‐analyses due to the limited available data.

Main results

We included three studies with 83 participants. For efficacy, a greater proportion of participants in the topiramate group had a 50% or more reduction in primarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (PGTCS) compared with participants in the placebo group. There were no significant differences between topiramate versus valproate in participants responding with a 50% or more reduction in myoclonic seizures or in PGTCS or seizure‐free. Concerning tolerability, we ranked AEDs associated with topiramate as moderate‐to‐severe, while we ranked 59% of AEDs linked to valproate as severe complaints. Moreover, systemic toxicity scores were higher in the valproate group than the topiramate group. We judged the quality of the evidence from the studies to be very low.

Authors' conclusions

Since the last version of this review we found no new studies. This review does not provide sufficient evidence to support topiramate for the treatment of people with JME. Based on the current limited available data, topiramate seems to be better tolerated than valproate, but there were no more benefits of efficacy in topiramate compared with valproate. In the future, well‐designed, double‐blind RCTs with large samples are required to test the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate in people with JME.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Humans; Young Adult; Anticonvulsants; Anticonvulsants/adverse effects; Anticonvulsants/therapeutic use; Fructose; Fructose/adverse effects; Fructose/analogs & derivatives; Fructose/therapeutic use; Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile; Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Seizures; Seizures/drug therapy; Treatment Outcome; Valproic Acid; Valproic Acid/adverse effects; Valproic Acid/therapeutic use

Topiramate monotherapy for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Background

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) is characterized by involuntary (uncontrolled) twitching of muscles in shoulders and arms after awakening, often starting in childhood.

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases for clinical trials comparing the antiepileptic drug, topiramate, with placebo (a pretend treatment) or another antiepileptic drug in people with JME. We wanted to evaluate how well topiramate worked and if it had any side effects. The evidence is current to February 2017.

Key results

We included and analyzed three randomized controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) with 83 participants. It seems that topiramate is better tolerated than valproate, but is no more effective than valproate. Topiramate seemed to work better than placebo based on a small number of included people.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence from the studies was very low and results should be interpreted with caution. In the future, well‐designed, double‐blind (where neither the participant nor the researcher know which treatment has been given until after the results have been collected) RCTs with large numbers of participants are required to test how effective and well tolerated topiramate is in people with JME.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Topiramate compared with placebo for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

| Topiramate compared with placebo for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy Settings: 18 centers in the USA; 10 centers in Europe; 1 center in Costa Rica Intervention: topiramate Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topiramate | |||||

| Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS) | 182 per 1000 |

727 per 1000 (197 to 1000) |

RR 4.00 (1.08 to 14.75) | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | More participants taking topiramate responded with a 50% or more reduction in PGTCS compared with placebo (P = 0.04) |

| Proportion of participants who experienced at least one AE and individual AEs | See comment | See comment | NA | 22 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Number of participants experiencing at least one AE was not reported. Individual AEs: no significant differences were found in nausea, URTI, abnormal vision, or diarrhea between topiramate versus placebo |

| Number of participants who were seizure‐free | Not reported | Not reported | NA | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the event rate in the control group. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AE: Adverse event;CI: Confidence interval; PGTCS: primarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures; RR: Risk Ratio; URTI: Upper respiratory tract infection | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1The included trials were reported as randomized, double‐blind trials with insufficient methodological information 2A relatively small number of participants

Summary of findings 2.

Topiramate compared with valproate for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

| Topiramate compared with valproate for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy Settings: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, USA; Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea Intervention: topiramate Comparison: valproate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Valproate | Topiramate | |||||

| Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in myoclonic seizures) | 1000 per 1000 |

857 per 1000 (670 to 1000) |

RR 0.88 (0.67 to 1.15) | 23 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | No significant difference was found |

| Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS) | 750 per 1000 |

917 per 1000 (510 to 1000) |

RR 1.22 (0.68 to 2.21) | 16 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | No significant difference was found |

| Proportion of participants who experienced at least one AE and individual AEs | See comment | See comment | NA | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Number of participants experiencing at least one AE was not reported. In Levisohn 2007 and Park 2013, we found significant differences in the AEs of paresthesia, weight gain and tremor. Moreover, no significant difference was found in headache, concentration difficulty, fatigue, alopecia, dizziness, weight loss, psychomotor slowing, somnolence, nausea, appetite increase, insomnia, abnormal vision, rash, anorexia, hallucination or diarrhea |

| Number of participants who were seizure‐free | 563 per 1000 |

636 per 1000 (343 to 1188) |

RR 1.13 (0.61 to 2.11) | 27 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | No significant difference was found |

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the event rate in the control group. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AE: Adverse event; CI: Confidence interval; PGTCS: primarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 The included trials were reported as randomized, double‐blind trials with insufficient methodological information 2 A relatively small number of participants

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Liu 2015) on 'Topiramate monotherapy for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy'.

Description of the condition

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) was first described by Janz in 1985. It is a primary generalized epilepsy, which is characterized by irregular myoclonic jerks of shoulders and arms after awakening and bilateral synchronous four to six per second spike‐wave complexes (Janz 1985). JME accounts for 5% to 11% of all epilepsy cases and its prevalence varies between 10 and 20 per 100,000 population (Jallon 2005; Panayiotopoulos 1991). Age of onset ranges from six to 22 years old, but 50% of cases present between 13 and 16 years of age. Valproate is widely regarded as the first‐line therapy in JME owing to its broad spectrum of activity. However, there remains 20% of people with JME who do not achieve satisfactory control with valproate (Calleja 2001). In addition, it is generally acknowledged that JME requires lifelong therapy and the adverse effects (AE) in chronic valproate therapy are extensive (Sharpe 2008). Thus, alternative effective broad‐spectrum agents are required.

Description of the intervention

Topiramate is a newer broad‐spectrum agent that is effective in many seizure types, including focal onset and primarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (PGTCS) and Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome (Biton 1999; Guberman 2002; Sachdeo 1999). Topiramate monotherapy during the first year after onset controls GTCS in 62.5% of people and myoclonic jerks in 68.8% of people, although 13.6% of people have an increase in frequency of absence seizures (Alfradique 2007). Moreover, topiramate has less risk of teratogenicity than valproate, and can be used as an alternative first‐line agent in women of childbearing age (Montouris 2009).

How the intervention might work

As a sulphamate‐substituted monosaccharide, the main mode of action of topiramate is through the inhibition of carbonic anhydrase. Meanwhile, it also has antiepileptic activity, which is probably attributed to other mechanisms, including modulation of voltage‐dependent sodium channels, potentiation of GABAergic inhibition at a novel site on the gamma‐aminobutyric acid‐A (GABA‐A) receptor and possible action at N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Hanaya 1998; White 2000; Zona 1997).

Why it is important to do this review

Some studies found topiramate effective in people with JME. However, no systematic review currently exists in the peer‐reviewed literature that focuses on this subject. This review aims to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate monotherapy for people with JME.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate monotherapy in the treatment of JME.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of topiramate monotherapy versus placebo or other antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment for people with JME. We included randomized cross‐over studies in meta‐analyses using the results from paired analyses (Elbourne 2002).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

People with a confirmed diagnosis of JME. Diagnostic criteria included myoclonic jerks and seizure onset in adolescence. We applied no limitation of age for enrolment.

People with co‐existent PGTCS with electroencephalogram (EEG)‐confirmed JME were also eligible.

Exclusion criteria

Previous discontinuation of topiramate owing to an AE

Co‐therapy with any other AED

Use of an experimental medication or device within 30 days of study entry

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention: topiramate monotherapy

Control intervention: placebo or other AED treatment

Different control groups were separately analyzed

Types of outcome measures

We collected and analyzed the outcomes of all the participants initially randomized by intention‐to‐treat (ITT).

Primary outcomes

Efficacy

Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction from baseline to end of treatment)

Secondary outcomes

Efficacy

Number of participants who were seizure‐free

Tolerability

Proportion of participants who experienced at least one AE

Proportion of participants who experienced each individual AE, such as ataxia, dizziness, fatigue or nausea

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Searches were run for the original review in July 2012 and subsequent searches were run on 2 November 2015 and 21 February 2017. For the latest update we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Epilepsy's Specialized Register (21 February 2017) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 1;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRSO, 21 February 2017) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE (Ovid; 1946 to 21 February 2017) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 3;

ClinicalTrials.gov (21 February 2017) using the search terms: (topiramate OR topamax OR "McN 4853" OR epitomax) AND (myoclonic OR Janz OR "petit mal").

Previously we also searched Embase (1 July 2015) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 4. It is no longer necessary to search Embase, because randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials in Embase are now included in CENTRAL.

Searching other resources

We also:

searched reference lists of articles obtained from any source;

searched conference proceedings likely to contain trials relevant to the review;

contacted researchers, pharmaceutical companies and relevant trial authors to seek information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

We did not impose any language restrictions on our searches, and we attempted to obtain translations of articles where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LJ, WL) independently evaluated titles and abstracts of identified trials to determine if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We obtained all potentially relevant studies for further consideration. We listed the excluded studies and reported the reasons for exclusion. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by an independent party if necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LJ, WL) independently extracted eligible data from the published reports onto standardized forms, and cross‐checked them for accuracy. We resolved disagreements regarding data extraction by consensus between the review authors.

We used checklists to record independently details of the following:

study design;

total study duration;

methods of generating randomization schedule;

method of concealment of allocation;

blinding;

use of an ITT analysis (all participants initially randomized were included in the analyses as allocated to groups);

AEs and drop‐outs for all reasons;

participants (country, number of participants, age, gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria);

comparison (details of the intervention in treatment and control groups, details of co‐intervention(s) in both groups, duration of treatment);

outcomes and time points of measures (number of participants in each group and outcome, regardless of compliance);

factors for heterogeneity (sample size, missing participants, confidence interval (CI) and P value in measurement, subgroup analyses).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LJ, WL) independently assessed methodological quality according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed six specific domains including: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other bias. We judged the result in each domain as 'low risk' of bias, 'high risk' of bias or 'unclear risk' of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We tried to evaluate the data from all the participants initially randomized as far as practically possible. We expressed continuous outcomes as mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. Outcomes such as the proportion of responders were commonly reported as dichotomous outcomes; we used risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI to express the effect size. If a trial (or group within a trial) reported no AEs or drop‐outs, we calculated risk differences (RD) instead of RRs with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

For any unit of analysis issues, we dealt with them according to The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the principal investigator for further details if any data were missing. According to ITT analysis, all randomized participants were included. We planned to assign zero improvement of dichotomous outcomes for the withdrawals. We planned to consider different scenarios (best‐case and worst‐case) to account for missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use the standard Chi2 statistic and I2 statistic (Higgins 2003) to measure heterogeneity (Deeks 2011), and make a judgement according to the visual inspection of forest plots. For the Chi2 test, we would have rejected the hypothesis of tolerability if the P value was less than 0.10 and an I2 greater than 50% would represent significant heterogeneity. In this case, we would have tried to explore factors for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess the publication bias by funnel plot if we had found more than 10 studies. However, the review included only three studies.

Data synthesis

If we found neither clinical nor statistical heterogeneity, we planned to pool results using a fixed‐effect model. We would have analyzed different controls separately. For statistical heterogeneity, we planned to incorporate the results into a random‐effects model. For heterogeneity that could not be readily explained, we would not have pooled the data but only given a description of the results.

Summary of findings and quality of the evidence (GRADE)

In a post‐hoc change, we have presented two 'Summary of findings' tables; one for each comparison (Table 1; Table 2). We reported all outcomes in the tables but made a general statement about the summary of findings for individual adverse events and graded the evidence based on consideration of the evidence of all of the adverse events (Schünemann 2011).

We determined the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach and downgraded evidence due to the presence of high risk of bias in at least one study, indirectness of the evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of results, high probability of publication bias. We downgraded evidence by one level if we considered the limitation to be serious and by two levels if very serious (GRADE 2013).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to analyze subgroups of studies categorized according to different doses and durations of topiramate.

As a formal method of comparing subgroups, we used the Chi2 test (to test for significant differences between subgroups of participants). For all statistical analyses, we used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014).

However, we did not perform subgroup analyses due to the limited available data.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses for unexplained heterogeneity, such as the exclusion of cross‐over trials from the analysis, the robustness of results to fixed‐effect versus random‐effects assumptions and the inclusion or exclusion of studies at high risk of bias, with inadequate allocation concealment or lack of blinded outcome assessor. We planned to use best‐case and worst‐case scenarios for taking into account missing data.

However, we performed no sensitivity analyses due to the limited available data.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

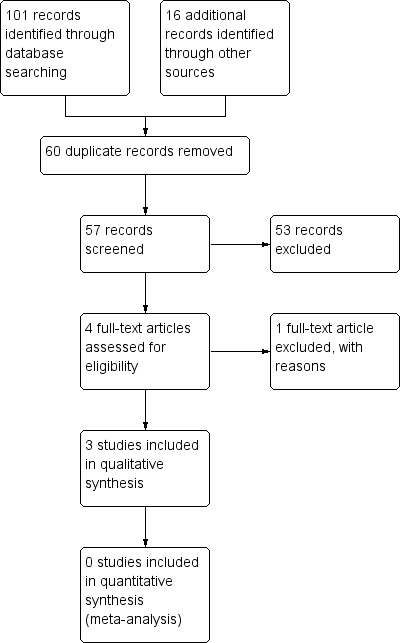

We updated the searches on 21 February 2017. We identified no papers in Cochrane Epilepsy’s Specialized Register and one paper each in CENTRAL, MEDLINE and ClinicalTrials.gov. Together with the last version, we identified 57 papers after de duplicating the results (Figure 1). After screening the titles and abstracts, we obtained the full papers of four studies and assessed them for eligibility. We excluded one study, because it was non‐randomized. There were no ongoing RCTs.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Three randomized studies with 83 participants met the inclusion criteria.

One study enrolled 22 people with JME and evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate versus placebo (Biton 2005). The starting dose of topiramate 50 mg/day or equivalent placebo tablets was maintained for four weeks, then increased at two‐week intervals to target dosages of 400 mg/day in adults or 6 mg/kg/day in children. Treatment was continued for an additional 12 weeks.

Two studies focused on the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate versus valproate in people with JME (Levisohn 2007; Park 2013).

In Levisohn 2007, 28 participants were assigned at a 2:1 ratio to topiramate (19 participants) or valproate (nine participants) for 26 weeks. The topiramate target dosage was 3 mg/kg/day to 4 mg/kg/day (maximum 9 mg/kg/day) for participants aged 12 to 16 years and 200 mg/day (maximum 600 mg/day) for participants aged over 16 years. Valproate target dosages were 10 mg/kg/day in participants aged 12 to 16 years (overall maximum 60 mg/kg/day) and 750 mg/day in participants aged over 16 years. Medications were titrated at one‐ to two‐week intervals according to clinical response and were administered in divided doses.

In Park 2013, 33 participants were assigned at a 1:1 ratio to topiramate (16 participants) or valproate (17 participants) for 32 weeks. The assigned AED was titrated up to 1200 mg/day for valproate or 100 mg/day for topiramate. The dose of valproate was titrated up 300 mg/day for two weeks, whereas topiramate was increased 25 mg/day for two weeks. In participants with a poor response to medication during the 24‐week maintenance phase, the dose of valproate was increased 300 mg/day for one month to a maximum dose of 2400 mg/day, and the dose of topiramate was increased 50 mg/day for one month to a maximum 300 mg/day. Further details of the included studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

We excluded one study after full‐text evaluation (Sousa Pda 2005). The reason for exclusion was due to the non‐randomized design (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

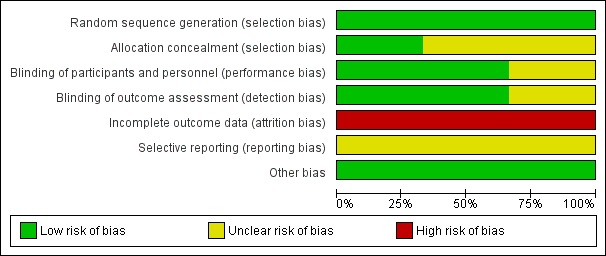

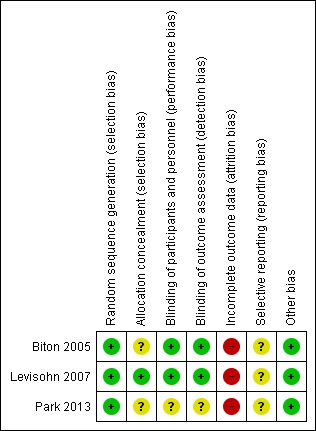

Risk of bias in included studies

All three included studies were subject to an assessment of bias on six domains. The information regarding risk of bias is provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

All three included studies reported the method of random sequence generation and we assessed them as at low risk of bias. However, only one study described the details of allocation concealment (Levisohn 2007). For the studies without information of allocation concealment, we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Two studies were double‐blind RCTs with low risk of bias (Biton 2005; Levisohn 2007). One study was open‐label, without information of blinding, therefore, we evaluated this at high risk of bias (Park 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

All three studies had incomplete outcome data. The proportion of participants who discontinued was more than 10% in all the studies. Therefore, we assessed all three studies at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We intended to use the table of 'Outcome Reporting Bias In Trials (ORBIT)' to evaluate selective outcome reporting (Kirkham 2010). However, the reporting bias could not be assessed as none of pre‐published protocols were available.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no other potential sources of bias. Insufficient numbers of trials were available for a funnel plot analysis.

Effects of interventions

Efficacy

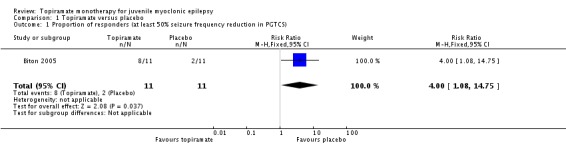

Topiramate versus placebo

In Biton 2005, significantly more participants taking topiramate responded with a 50% or more reduction in PGTCS compared with placebo (73% with topiramate versus 18% with placebo; (RR 4.00, 95% CI 1.08 to 14.75, P = 0.04) (Analysis 1.1). The median PGTCS reduction after 20 weeks was 64% in the topiramate group and 38% in the placebo group, which was not significantly different. Topiramate improved control of myoclonic seizures, including an increase in the number of weeks without myoclonic seizures (171% increase with topiramate versus 130% increase with placebo), which was not significantly different. The number of absence‐free weeks was increased by 15% in topiramate group, but decreased by 7% in placebo group (P = 0.07). Three participants taking topiramate had no PGTCS and one had no myoclonic seizures, and two participants taking placebo had no PGTCS. In five participants taking placebo, seizure frequency increased more than 50% from baseline (PGTCS, one participant; absence, three participants; myoclonic, one participant), while seizure frequency increased more than 50% in two participants taking topiramate (absence, one participant; myoclonic, one participant).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Topiramate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS).

Topiramate versus valproate

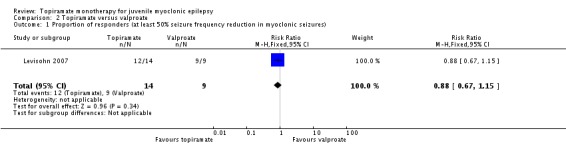

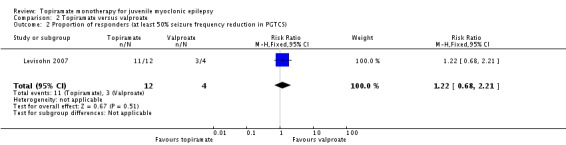

In Levisohn 2007 using ITT, fewer participants taking topiramate responded with a 50% or more reduction in myoclonic seizures compared with valproate, which was not significantly different (85% with topiramate versus 100% with valproate, (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.15)) (Analysis 2.1). However, more participants taking topiramate responded with a 50% or more reduction in PGTCS compared with valproate, which was not significantly different (91% with topiramate versus 75% with valproate, (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.21) ) (Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 1 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in myoclonic seizures).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 2 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS).

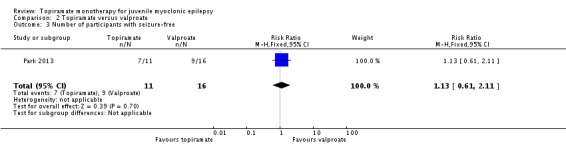

For Park 2013, 11/16 (68.9%) participants in the topiramate group completed 24‐week maintenance therapy, in which 7/11 (64%) were seizure‐free. While 16/17 (94.1%) participants in the valproate group completed 24‐week follow‐up, in which 9/16 (56%) were seizure‐free. This was not significantly different ((RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.11) (Analysis 2.3).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 3 Number of participants with seizure‐free.

In Levisohn 2007, 8/12 (67%) participants in the topiramate group and 4/7 (57%) participants in the valproate group had no seizures during the 12‐week maintenance period. Physicians reported that 73% of participants experienced marked/moderate global improvement with topiramate or valproate treatment, whereas 56% of participants felt that they had experienced marked/moderate improvement. According to physicians and participants, 43% of topiramate‐treated participants and 14% of valproate‐treated participants experienced marked/moderate improvement in alertness. Alertness worsened in one valproate‐treated participant.

Tolerability

None of the studies reported the number of participants who experienced at least one AE.

Topiramate versus placebo

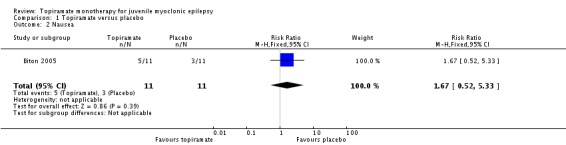

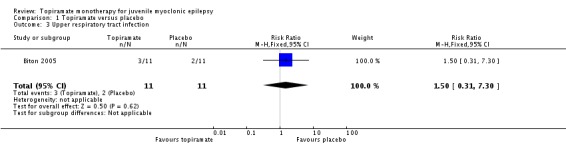

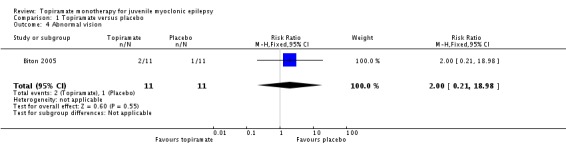

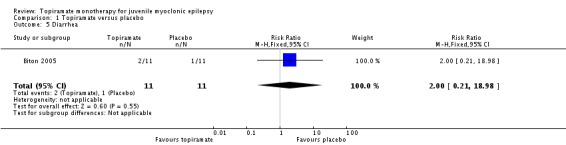

In Biton 2005, we found no significant difference in the AEs of nausea (Analysis 1.2), upper respiratory tract infection (Analysis 1.3), abnormal vision (Analysis 1.4), or diarrhoea (Analysis 1.5) between topiramate versus placebo.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Topiramate versus placebo, Outcome 2 Nausea.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Topiramate versus placebo, Outcome 3 Upper respiratory tract infection.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Topiramate versus placebo, Outcome 4 Abnormal vision.

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Topiramate versus placebo, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

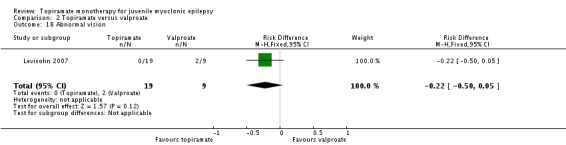

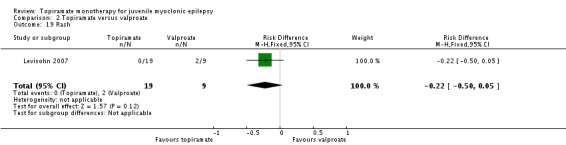

Topiramate versus valproate

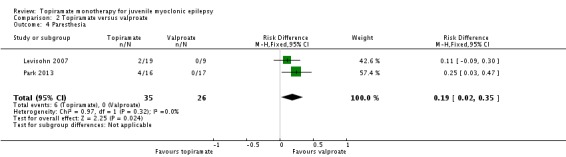

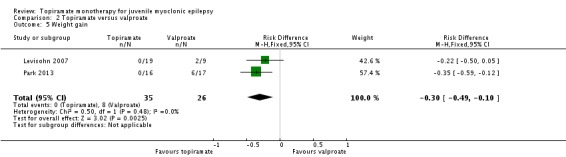

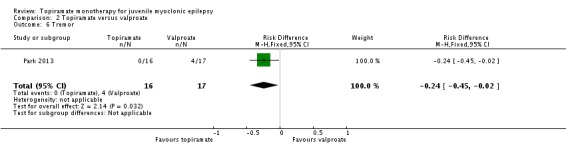

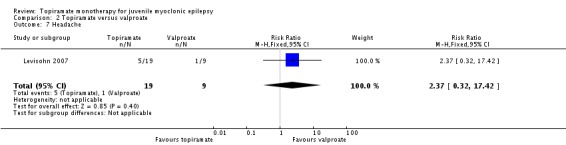

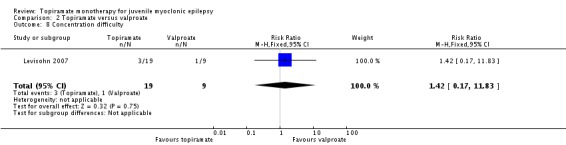

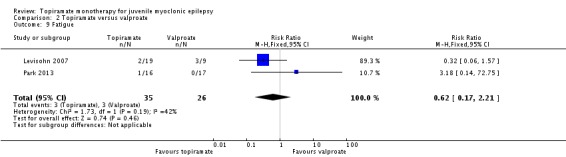

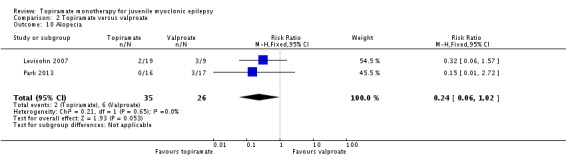

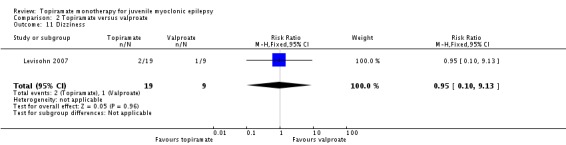

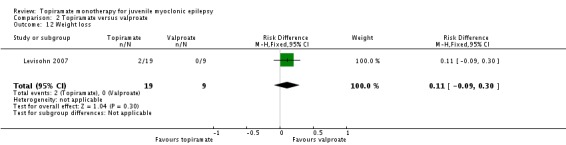

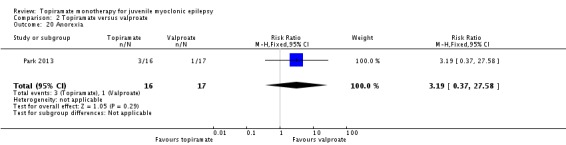

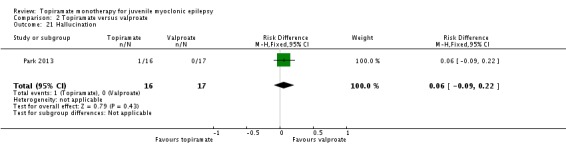

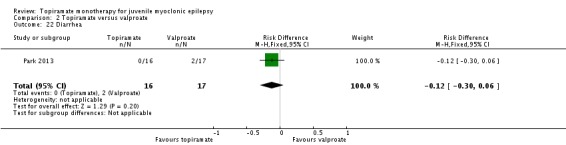

In Levisohn 2007 and Park 2013, we found significant differences in the AEs of paresthesia (Analysis 2.4), weight gain (Analysis 2.5), and tremor (Analysis 2.6). There was no significant difference in headache (Analysis 2.7), concentration difficulty (Analysis 2.8), fatigue (Analysis 2.9), alopecia (Analysis 2.10), dizziness (Analysis 2.11), weight loss (Analysis 2.12), psychomotor slowing (Analysis 2.13), somnolence (Analysis 2.14), nausea (Analysis 2.15), appetite increase (Analysis 2.16), insomnia (Analysis 2.17), abnormal vision (Analysis 2.18), rash (Analysis 2.19), anorexia (Analysis 2.20), hallucination (Analysis 2.21) or diarrhea (Analysis 2.22).

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 4 Paresthesia.

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 5 Weight gain.

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 6 Tremor.

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 7 Headache.

Analysis 2.8.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 8 Concentration difficulty.

Analysis 2.9.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 9 Fatigue.

Analysis 2.10.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 10 Alopecia.

Analysis 2.11.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 11 Dizziness.

Analysis 2.12.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 12 Weight loss.

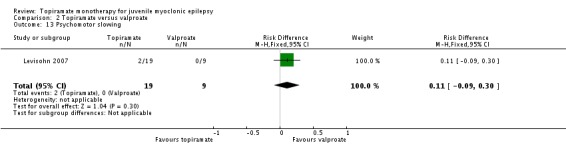

Analysis 2.13.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 13 Psychomotor slowing.

Analysis 2.14.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 14 Somnolence.

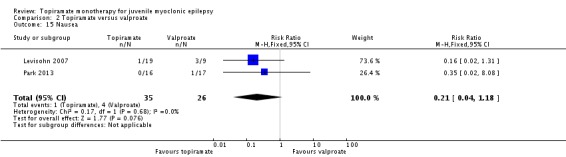

Analysis 2.15.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 15 Nausea.

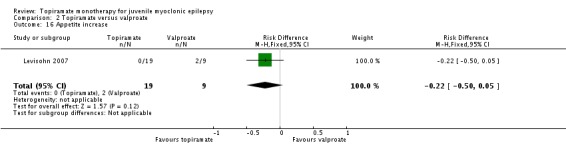

Analysis 2.16.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 16 Appetite increase.

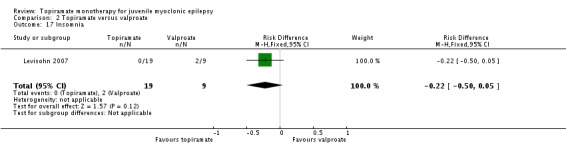

Analysis 2.17.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 17 Insomnia.

Analysis 2.18.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 18 Abnormal vision.

Analysis 2.19.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 19 Rash.

Analysis 2.20.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 20 Anorexia.

Analysis 2.21.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 21 Hallucination.

Analysis 2.22.

Comparison 2 Topiramate versus valproate, Outcome 22 Diarrhea.

In Levisohn 2007, systemic toxicity scores were higher in participants taking valproate at each evaluation (at four, eight, 14 and 26 weeks). Neurotoxicity scores did not substantially differ between treatment groups.

Discussion

Summary of main results

For efficacy, there were significantly more participants in the topiramate group with a 50% or more reduction in PGTCS than participants in placebo group (Biton 2005). There were no significant differences between topiramate versus valproate in participants who responded with a 50% or more reduction in myoclonic seizures or in PGTCS (Levisohn 2007), or who were seizure‐free (Park 2013). Concerning tolerability, 23 AEs occurred in 11 participants taking topiramate and seven AEs in 11 participants taking placebo (Biton 2005). AEs associated with topiramate were ranked as moderate‐to‐severe, while 59% of AEs linked to valproate were ranked as severe complaints (Park 2013). Moreover, systemic toxicity scores were higher in valproate group than topiramate group (Levisohn 2007).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence for topiramate in the treatment of JME was insufficient. Because of the limited number of included studies and substantial heterogeneity in comparison (different controls) and outcomes design, meta‐analysis was not applicable. We found high risk of bias in incomplete outcome data in all the three RCTs. Furthermore, the sample size of randomized participants was too small to reach a robust conclusion. For topiramate versus placebo, 22 participants were randomized, while there were 61 participants randomized in topiramate versus valproate. Therefore, studies with high‐quality and large samples are required to strengthen the applicability of evidence.

Quality of the evidence

The limitations of methodology were found in all the included studies. Two RCTs did not provide any information of allocation concealment, therefore, we assessed them as unclear risk of bias (Biton 2005; Park 2013). One RCT was not of double‐blind design with high risk of bias in blinding (Park 2013). In all three RCTs, attrition bias was high risk (Biton 2005; Levisohn 2007; Park 2013). We could not assess reporting bias as none of the pre‐published protocols were available. Therefore, we regard the quality of evidence to be very low and the conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

Potential biases in the review process

The search for trials was rigorously performed based on the strategies in different electronic databases. To identify unpublished or incomplete trials, we also searched for protocols, but found no eligible studies. In addition, due to the inclusion of only three RCTs, we could not assess publication bias using funnel plots. Therefore, we could not exclude the possibility that we did not identify unpublished trials.

Authors' conclusions

Since the last version of this review we have found no new studies. This review does not provide sufficient evidence to support topiramate for the treatment of people with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). Based on the current limited data, topiramate seems to be better tolerated than valproate, but was no more efficacious than valproate. The evidence base for the choice of the most appropriate antiepileptic drug (AED) for JME is very weak.

Well‐designed, double‐blind randomised controlled trials with large samples are required to test the efficacy and tolerability of topiramate in people with JME. Short‐term studies on seizure outcomes when taking AEDS compared with not taking AEDs are helpful to provide a more complete view of the efficacy of current AEDs for JME.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help provided by Cochrane Epilepsy.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Epilepsy Specialized Register search strategy

#1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile Explode All

#2 "myoclonic epilepsy" OR "impulsive petit mal" OR "Janz syndrome"

#3 #1 OR #2

#4 topiramate OR topamax OR epitomax OR "McN 4853" OR "McN‐4853" OR "2,3:4,5‐bis‐O‐(1‐methylethylidene)‐beta‐D‐fructopyranose sulfamate"

#5 #3 AND #4

#6 #5 AND >02/11/2015:CRSCREATED

Appendix 2. CENTRAL via Cochrane Register of Studies Online search strategy

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile EXPLODE ALL TREES

#2 "myoclonic epilepsy"

#3 "impulsive petit mal"

#4 "Janz syndrome"

#5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4

#6 topiramate OR topamax OR epitomax OR "McN 4853" OR "McN‐4853" OR "2,3:4,5‐bis‐O‐(1‐methylethylidene)‐beta‐D‐fructopyranose sulfamate"

#7 #5 AND #6

#8 02/11/2015 TO 21/02/2017:CD

#9 #7 AND #8

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

This strategy is based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials published in Lefebvre 2011.

1. (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trialor pragmatic clinical trial).pt. or (randomi?ed or placebo or randomly).ab.

2. clinical trials as topic.sh.

3. trial.ti.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

6. 4 not 5

7. exp Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile/

8. (myoclonic epilepsy or impulsive petit mal or Janz syndrome).tw.

9. 7 or 8

10. (topiramate or topamax or epitomax or "McN 4853" or "McN‐4853" or "2,3:4,5‐bis‐O‐(1‐methylethylidene)‐beta‐D‐fructopyranose sulfamate").tw.

11. 6 and 9 and 10

12. remove duplicates from 11

13. limit 12 to ed=20151102‐20170221

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

1. 'randomized controlled trial'/exp

2. 'controlled clinical trial'/exp

3. random*:ab.

4. placebo.ab.

5. 'clinical trial':ab.

6. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5

7. 'Myoclonic Epilepsy, Juvenile'/exp

8. myoclonic epilepsy:ab.

9. impulsive petit mal:ab.

10. Janz syndrome:ab.

11. 7 or 8 or 9 or 10

12. 'topiramate'/exp

13. topamax:ab.

14. epitomax:ab.

15. McN 4853:ab.

16. "2,3:4,5‐bis‐O‐(1‐methylethylidene)‐beta‐D‐fructopyranose sulfamate":ab.

17. 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

22. 6 and 11 and 17

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Topiramate versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS) | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [1.08, 14.75] |

| 2 Nausea | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.52, 5.33] |

| 3 Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.31, 7.30] |

| 4 Abnormal vision | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.21, 18.98] |

| 5 Diarrhea | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.21, 18.98] |

Comparison 2.

Topiramate versus valproate

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in myoclonic seizures) | 1 | 23 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.15] |

| 2 Proportion of responders (at least 50% seizure frequency reduction in PGTCS) | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.68, 2.21] |

| 3 Number of participants with seizure‐free | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.61, 2.11] |

| 4 Paresthesia | 2 | 61 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.02, 0.35] |

| 5 Weight gain | 2 | 61 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐0.49, ‐0.10] |

| 6 Tremor | 1 | 33 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.45, ‐0.02] |

| 7 Headache | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.37 [0.32, 17.42] |

| 8 Concentration difficulty | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.17, 11.83] |

| 9 Fatigue | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.17, 2.21] |

| 10 Alopecia | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.06, 1.02] |

| 11 Dizziness | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.10, 9.13] |

| 12 Weight loss | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.09, 0.30] |

| 13 Psychomotor slowing | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.09, 0.30] |

| 14 Somnolence | 2 | 61 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.05, 0.21] |

| 15 Nausea | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.04, 1.18] |

| 16 Appetite increase | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.50, 0.05] |

| 17 Insomnia | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.50, 0.05] |

| 18 Abnormal vision | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.50, 0.05] |

| 19 Rash | 1 | 28 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.50, 0.05] |

| 20 Anorexia | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.19 [0.37, 27.58] |

| 21 Hallucination | 1 | 33 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.09, 0.22] |

| 22 Diarrhea | 1 | 33 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.30, 0.06] |

What's new

Last assessed as up‐to‐date: 21 February 2017.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 February 2017 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 21 February 2017; no new trials identified |

| 21 February 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions are unchanged |

Differences between protocol and review

We added 'number of participants who were seizure‐free' as the secondary outcome.

We added 'Summary of findings' tables for all outcomes.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study | |

| Participants | 22 participants with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | |

| Interventions | Starting dose of topiramate 50 mg/day or equivalent placebo tablets was maintained for 4 weeks, then increased at 2‐week intervals to target dosages of 400 mg/day in adults or 6 mg/kg/day in children. Treatment was continued for an additional 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Reduction in PGTCS, myoclonic, absence and total generalized seizures, adverse events | |

| Notes | The baseline period was 8 weeks. The protocol can be identified from Biton 1999 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A computer‐generated randomization schedule was prepared by the Robert Wood Johnson Pharmaceutical Research Institute before the beginning of the trial |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment was not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | During the double‐blind phase, investigators, participants, study monitors and observers remained masked to codes until after the clinical database was finalized |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | During the double‐blind phase, investigators, participants, study monitors and observers remained masked to codes until after the clinical database was finalized |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 2 participants taking topiramate (18%) and 1 (9%) participant taking placebo discontinued treatment owing to adverse events |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No prepublished protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias was found |

| Methods | Pilot, randomized controlled trial | |

| Participants | 28 participants with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | |

| Interventions | Participants were assigned as 2:1 ratio to topiramate (19 participants) or valproate (9 participants) for 26 weeks. The topiramate target dosage was 3‐4 mg/kg/day (maximum 9 mg/kg/day) for participants aged 12‐16 years and 200 mg/day (maximum 600 mg/day) for participants aged > 16 years. Valproate target dosages were 10 mg/kg/day in participants aged 12‐16 years and 750 mg/day in participants aged >16 years (overall maximum 60 mg/kg/day). Medications were titrated at 1‐ to 2‐week intervals according to clinical response and were administered in divided doses | |

| Outcomes | Seizure reduction, evaluation of improvement, systemic toxicity and neurotoxicity scores, adverse events | |

| Notes | The baseline period was 3 months before study entry. A 14‐week titration phase was followed by a 12‐week maintenance phase | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Blinded randomization was achieved by providing study sites with individual envelopes containing medication assignments generated by computer |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Blinded randomization was achieved by providing study sites with individual envelopes containing medication assignments generated by computer |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The participant, investigator and pharmacist remained blinded to medication assignment until screening was completed and the envelope was opened |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The participant, investigator and pharmacist remained blinded to medication assignment until screening was completed and the envelope was opened |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 7 (37%) participants treated with topiramate and 2 (22%) participants treated with valproate discontinued before the endpoint |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No pre published protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias was found |

| Methods | Randomized open‐label observational study | |

| Participants | 33 participants with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | |

| Interventions | Participants were assigned as 1:1 ratio to topiramate (16 participants) or valproate (17 participants) for 32 weeks. The assigned antiepileptic drug was titrated up to 1200 mg/day for valproate or 100 mg/day for topiramate. The dose of valproate was titrated up 300 mg/day for 2 weeks, whereas topiramate was increased 25 mg/day for 2 weeks. In participants with a poor response to medication during the 24‐week maintenance phase, the dose of valproate was increased 300 mg/day for 1 month to a maximum dose of 2400 mg/day, and the dose of topiramate was increased 50 mg/day for 1 month to a maximum 300 mg/day | |

| Outcomes | Number of days without myoclonic seizures during the 24‐week maintenance period, adverse events | |

| Notes | Baseline period was not clear. An 8‐week titration phase was followed by a 24‐week maintenance phase | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants underwent computerized randomization in a 1 : 1 ratio to primary treatment with topiramate or valproate |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 1 (6%) participant who was randomized to topiramate was removed from the study due to severe anorexia. 4 (25%) participants from the topiramate group and 1 (6%) participant from the valproate group were lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No pre published protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias was found |

PGTCS: primarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Sousa Pda 2005 | Not a randomized controlled trial |

Contributions of authors

Liu J and Wang LN formulated the idea and developed the basis for the review.

The manuscript was completed by Liu J and Wang LN, and revised by Wang YP.

Liu J was responsible for updating the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

This review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Epilepsy. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Declarations of interest

Jia Liu; none known Lu‐Ning Wang: none known Yu‐Ping Wang: none known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

- Biton V, Bourgeois BF, YTC/YTCE Study Investigators. Topiramate in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Archives of Neurology 2005;62:1705‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levisohn PM, Holland KD. Topiramate or valproate in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a randomized open‐label comparison. Epilepsy & Behavior 2007;10:547‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KM, Kim SH, Nho SK, Shin KJ, Park J, Ha SY, et al. A randomized open‐label observational study to compare the efficacy and tolerability between topiramate and valproate in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2013;20:1079‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Sousa Pda S, Araújo Filho GM, Garzon E, Sakamoto AC, Yacubian EM. Topiramate for the treatment of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Arquivos de Neuro‐psiquiatria 2005;63:733‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Alfradique I, Vasconcelos MM. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Arquivos de Neuro‐psiquiatria 2007;65:1266‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biton V, Montouris GD, Ritter F, Riviello JJ, Reife R, Lim P, et al. A randomized, placebo‐controlled study of topiramate in primary generalized tonic‐clonic seizures. Neurology 1999;52:1330‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja S, Salas‐Puig J, Ribacoba R, Lahoz CH. Evolution of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy treated from the outset with sodium valproate. Seizure 2001;10:424‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors). Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

- Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Higgins JP, Curtin F, Worthington HV, Vail A. Meta‐analyses involving cross‐over trials: methodological issues. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):140‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A (editors). Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Updated October 2013. gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html.

- Guberman A, Neto W, Gassmann‐Mayer C, EPAJ‐119 Study Group. Low‐dose topiramate in adults with treatment‐resistant partial‐onset seizures. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2002;106:183‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaya R, Sasa M, Ujihara H, Ishihara K, Serikawa T, Iida K, et al. Suppression by topiramate of epileptiform burst discharges in hippocampal CA3 neurons of spontaneously epileptic rat in vitro. Brain Research 1998;789:274‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

- Jallon P, Latour P. Epidemiology of idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Epilepsia 2005;46 (Suppl 9):S10‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz D. Epilepsy with impulsive petit mal (juvenile myoclonic epilepsy). Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 1985;72:449‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, Gamble C, Dodd S, Smyth R, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010;340:c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

- Montouris G, Abou‐Khalil B. The first line of therapy in a girl with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: should it be valproate or a new agent?. Epilepsia 2009;50(Suppl 8):16‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayiotopoulos CP, Tahan R, Obeid T. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: factors of error involved in the diagnosis and treatment. Epilepsia 1991;32:672‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

- Sachdeo RC, Glauser TA, Ritter F, Reife R, Lim P, Pledger G. Topiramate YL Study Group. A double‐blind, randomized trial of topiramate in Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. Neurology 1999;52:1882‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Guyatt GH. Chapter 11: Presenting results and ‘Summary of findings' tables. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

- Sharpe DV, Patel AD, Abou‐Khalil B, Fenichel GM. Levetiracetam monotherapy in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure 2008;17:64‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, Skeen GA, Wolf HH. Topiramate modulates GABA‐evoked currents in murine cortical neurons by a nonbenzodiazepine mechanism. Epilepsia 2000;41 Suppl 1:S17‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zona C, Ciotti MT, Avoli M. Topiramate attenuates voltage‐gated sodium currents in rat cerebellar granule cells. Neuroscience Letters 1997;231:123‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Liu J, Wang LN. Topiramate monotherapy for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010008] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang LN, Wang YP. Topiramate monotherapy for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010008.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]