Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the Cochrane review published in The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 1.

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder, affecting almost 0.5% to 1% of the population. For nearly 30% of these people, their epilepsy is refractory to currently available drugs. Pharmacological treatment remains the first choice to control epilepsy. Lamotrigine is one of the newer antiepileptic drugs and is the topic of this review. Lamotrigine in combination with other antiepileptic drugs (add‐on) can reduce seizures, but with some adverse effects. The aim of this systematic review was to overview the current evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of lamotrigine when used as an adjunctive treatment for people with refractory partial epilepsy.

Objectives

To determine the effects of lamotrigine on (1) seizures, (2) adverse effect profile, and (3) cognition and quality of life, compared to placebo controls, when used as an add‐on treatment for people with refractory partial epilepsy.

Search methods

For the previous version of the review, the authors searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (January 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 1), MEDLINE (1950 to January 2010), and reference lists of articles.

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (28 May 2015), CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 4), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to May 2015), and reference lists of articles. We also contacted the manufacturers of lamotrigine (GlaxoSmithKline). No language restrictions were imposed.

Selection criteria

Randomised placebo‐controlled trials of people with drug‐resistant partial epilepsy of any age, in which an adequate method of concealment of randomisation was used. The studies were double‐, single‐ or unblinded. For cross‐over studies, the first treatment period was treated as a parallel trial. Eligible participants were adults or children with drug‐resistant partial epilepsy.

Data collection and analysis

For this update, two review authors independently assessed the trials for inclusion, and extracted data. Outcomes included 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency, treatment withdrawal (any reason), adverse effects, effects on cognition and quality of life. Primary analyses were by intention‐to‐treat. Sensitivity best and worse case analyses were undertaken to account for missing outcome data. Pooled Risk Ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% Cl) were estimated for the primary outcomes of seizure frequency and treatment withdrawal. For adverse effects, pooled RRs and 99% Cls were calculated.

Main results

We did not identify any new studies for this update, therefore, the results are unchanged.

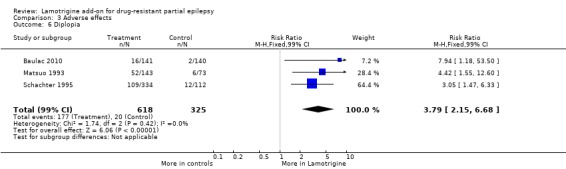

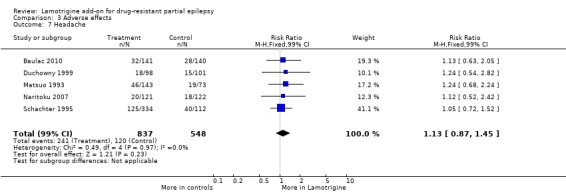

For the previous version of the review, the authors found five parallel add‐on studies and eight cross‐over studies in adults or children with refractory focal epilepsy, and one parallel add‐on study with a responder‐enriched design in infants. In total, these 14 studies included 1958 participants (38 infants, 199 children, and 1721 adults). Baseline phases ranged from 4 to 12 weeks; treatment phases from 8 to 36 weeks. Overall, eleven studies (n = 1243 participants) were rated as having a low risk of bias, and three (n = 715 participants) had un unclear risk of bias due to lack of reported information around study design. Effective blinding of studies was reported in three studies (n = 504 participants). The overall risk ratio (RR) for 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency was 1.80 (95% CI 1.45 to 2.23; 12 RCTs) for twelve studies (n = 1322 participants, adults and children) indicating that lamotrigine was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing seizure frequency. The overall RR for treatment withdrawal (for any reason) was 1.11 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.36; 14 RCTs) for fourteen studies (n = 1958 participants). The adverse events significantly associated with lamotrigine were: ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, and nausea. The RR of these adverse effects were as follows: ataxia 3.34 (99% Cl 2.01 to 5.55; 12 RCTs; n = 1524); dizziness 2.00 (99% Cl 1.51 to 2.64;13 RCTs; n = 1767); diplopia 3.79 (99% Cl 2.15 to 6.68; 3 RCTs; n = 943); nausea 1.81 (99% Cl 1.22 to 2.68; 12 RCTs; n = 1486). The limited data available precluded any conclusions about effects on cognition and quality of life. No important heterogeneity between studies was found for any of the outcomes. Overall, we assessed the evidence as high to moderate quality, due to incomplete data for some outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Lamotrigine as an add‐on treatment for partial seizures appears to be effective in reducing seizure frequency, and seems to be fairly well tolerated. However, the trials were of relatively short duration and provided no evidence for the long‐term. Further trials are needed to assess the long‐term effects of lamotrigine, and to compare it with other add‐on drugs.

Since we did not find any new studies, our conclusions remain unchanged.

Plain language summary

Adding lamotrigine for drug‐resistant partial epilepsy

Background

Epilepsy is a disorder in which unexpected electrical discharges from the brain cause seizures. Approximately one‐third of patients with epilepsy continue to have seizures, despite treatment with presently used (older) antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). In addition, the older AEDs have a lot of adverse effects.

Therefore, the development of effective new therapies for the treatment of refractory seizures is of considerable importance. As a result, a range of new AEDs has been developed as 'add‐on' treatments. Lamotrigine is one of these.

Aims of the review

This review aimed to determine the effects of lamotrigine on seizures, adverse effects, cognition (ability to learn and understand) and quality of life compared to placebo controls, when used as an add‐on treatment for people with partial epilepsy that would not respond to existing AEDs.

For this update, we did not identify any new studies to add, and thus, the conclusions remain unchanged. The review included 14 randomised controlled trials with a total number of 1958 participants.

Results

Lamotrigine, used in combination with other AEDs in patients who have drug‐resistant partial epilepsy can decrease the frequency of seizures further. However, adding lamotrigine to the usual treatment is more often associated with an increase in adverse effects such as unsteadiness (ataxia), dizziness, double vision (diplopia), and nausea.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the trials with regards to risk of bias. Overall, we rated the quality of the evidence as high.

Conclusions

Further high‐quality research is needed to fully evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of lamotrigine and compare it with other newer AEDs.

The evidence is current to 28 May 2015.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Lamotrigine versus placebo for drug‐resistant partial epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with drug‐resistant partial epilepsy Settings: outpatient setting Intervention: Lamotrigine versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Lamotrigine | |||||

| 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency ‐ ITT analysis | 157 per 1000 | 283 per 1000 (223 to 350) |

RR 1.80 (95% CI 1.45 to 2.23) |

1322 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| Treatment withdrawal | 159 per 1000 | 176 per 1000 (143 to 216) |

RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.36) |

1805 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| Ataxia | 45 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (90 to 250) |

RR 3.34 (99% CI 2.01 to 5.55) |

1524 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| Dizziness | 128 per 1000 | 256 per 1000 (193 to 338) |

RR 2.00 (99% CI 1.51 to 2.64) |

1767 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| Fatigue | 113 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (62 to 138) |

RR 0.82 (99% CI 0.55 to 1.22) |

1551 (12 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| Nausea | 83 per 1000 | 150 per 1000 (101 to 222) |

RR 1.81 (99% CI 1.22 to 2.68) |

1486 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | RR >1 indicates outcome is more likely in Lamotrigine group |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes4. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 One or two studies do not contribute to the analysis, but no other bias.

2 All studies contributed to the analysis.

3 Wide confidence intervals.

4Assumed risk is calculated as the event rate in the control group per 1000 people (number of events divided by the number of participants receiving control treatment).

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 1.

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is characterised by recurrent and unprovoked seizures, constituting a transient sign and symptom of abnormal, excessive electrical activity in the cerebral cortex (Fisher 2005). Epilepsy is one the most common serious neurological conditions worldwide, with significant psychosocial and physical morbidity. Its management requires expertise and good pharmacological knowledge of the available options (Lyer 2014). The condition affects approximately 50 million people worldwide. The total annual cost in Europe is approximately 15.5 billion Euros (Mula 2013). Between 2% and 3% of the population will be given a diagnosis of epilepsy at some time in their lives (Hauser 1993), the majority of whom will become seizure free. However, up to 30% will continue to have seizures, refractory to treatment with adequate doses of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), which are often given in combination (Cockerell 1995). There is no internationally accepted definition of "drug‐resistant". For the purposes of this review, people will be considered to be drug‐resistant if they have failed to respond to a minimum of two AEDs, given as monotherapy. The majority of drug‐resistant people have partial onset (also called focal or localization related) seizures. In other words, seizures start in one part of the brain and during the course of the seizure, the abnormal electrical activity remains localised or spreads to other parts of the brain. Partial seizures can be divided into three types: simple partial; complex partial, and secondarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures (Commission 1989).

Description of the intervention

Although more than a dozen new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have entered the market since 1993, up to 30% of patients remain refractory to current treatments. Thus, a concerted effort continues to identify and develop new therapies that will help these patients (Barker‐Haliski 2014). Pharmacological treatment remains the first choice for controlling epilepsy (Loscher 2002), although recent decades have seen advances in vagal stimulation (Panebianco 2015), and surgery (West 2015). Given that our standard drugs (e.g. carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproate) do not leave all people seizure free and are not without adverse effects, over the past 15 to 20 years, there has been renewed interest in the development of newer AEDs. One such drug is lamotrigine (LTG).

Lamotrigine is a novel AED, widely used in the treatment of epilepsy as adjunctive treatment for partial, secondarily generalised, and tonic‐clonic seizures in patients with refractory epilepsy, and bipolar disorder (Yamamoto 2012).

How the intervention might work

Lamotrigine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the USA in 1994 for use in partial‐onset seizures. It was ultimately approved for monotherapy in 1998. Lamotrigine is effective against a broad spectrum of seizure types and has a favourable metabolic profile. It has gained widespread use in the USA as both an immediate and an extended‐release agent (Moore 2012). Lamictal (GlaxoSmithKline) is considered the reference drug (Girolineto 2012). In vitro pharmacological studies suggest that the main mechanism of action of lamotrigine is to inhibit voltage‐sensitive sodium channels, thereby stabilizing neuronal membranes and consequently modulating presynaptic transmitter release of excitatory aminoacids, e.g. glutamate and aspartate (Leach 1995). Lamotrigine has been demonstrated to be effective as both an antiepileptic drug and a mood stabiliser (Vajda 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

In this review, we summarise evidence from randomised controlled trials where the efficacy and tolerability of lamotrigine for people with drug‐resistant partial epilepsy have been investigated, in order to aid clinical decision‐making when considering LTG as add‐on treatment within this population.

Antiepileptic drugs may impair people's cognitive abilities, and in this review, we include outcomes that assess cognitive effects. In addition, we have chosen to include quality‐of life outcomes, to assess the global impact of this drug on people's well‐being.

Objectives

To determine the effects of lamotrigine on (1) seizures, (2) adverse effect profile, and (3) cognition and quality of life, compared to controls, when used as an add‐on treatment for people with refractory partial epilepsy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included trials that met all the following criteria:

Randomised controlled trials, in which an adequate method of concealment of randomisation was used (e.g. allocation of sequentially sealed packages of medication, sealed opaque envelopes, telephone randomisation);

Double‐, single‐blind trials and unblinded trials;

Placebo‐controlled trials;

Parallel group and cross‐over studies. For cross‐over studies, the first treatment period was treated as a parallel trial, for the purposes of analysis of efficacy and safety data (i.e. only data from the first treatment period was used).

Types of participants

Individuals of any age with partial epilepsy (i.e. experiencing simple partial, complex partial, or secondarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures) who had failed to respond to at least one AED (drug‐resistant epilepsy).

Types of interventions

The treatment group received lamotrigine in addition to conventional antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment.

The control group received conventional AED treatment plus a matched placebo, or 'no treatment' control.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

Greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency during the treatment period, compared to the pre‐randomisation baseline frequency. We chose this outcome as it is commonly reported in this type of study and can be calculated for studies that do not report this outcome, provided that baseline seizure data were recorded.

Secondary outcomes

Treatment withdrawal

The proportion of participants who had treatment withdrawn during the course of the treatment period was chosen as a measure of global effectiveness. Treatment may be withdrawn due to adverse effects, lack of efficacy, or a combination, and this is an outcome to which the individual makes a direct contribution. However, in studies of relatively short duration, such as studies that would be included in this review, adverse effects were likely to be the main reason for treatment withdrawal.

Adverse effects

(a) The proportion of participants experiencing any of the following adverse effects, which we considered to be the most common and important adverse effects of AEDs:

ataxia;

dizziness;

fatigue;

nausea;

somnolence;

diplopia;

headache.

(b) The proportion of participants who experienced the five most common adverse effects in a study, if different from those stated above.

Cognitive effects

The difference between intervention and control group(s) means for cognitive assessments used in the individual studies.

Quality of life

The difference between intervention and control group(s) means for quality of life (QOL) assessments used in the individual studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the previous version of the review, the authors searched the following databases for relevant studies (Ramaratnam 2001):

The Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (January 2010).

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2010).

MEDLINE (1950 to January 2010).

For this update, we searched the following databases for relevant studies:

The Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (28 May 2015), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 1.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 4), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 2.

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 28 May 2015), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 3.

We imposed no language restrictions. We tailored searches to individual databases, and adapted from those used in the previous review.

Searching other resources

For the original review and this update, we checked reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies, and performed citation searches on key articles. We contacted experts in the field for unpublished and ongoing trials, and authors and manufacturers of lamotrigine (GlaxoSmithKline) for additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (SR and MP) independently assessed trials for inclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (AM). Two review authors (SR and MP) independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias for included trials; again, disagreements were resolved by mutual discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following data for each trial, using a data extraction form:

(1) Methods and trial design:

(a) Method of randomisation. (b) Method of allocation concealment. (c) Method of blinding. (d) Whether any participants had been excluded from reported analyses. (e) Duration of baseline period. (f) Duration of treatment period. (g) Dose(s) of LTG tested. (h) Information on Sponsorship and Funding.

(2) Participant and demographic information:

(a) Total number of participants allocated to each treatment group. (b) Age and sex. (c) Number with partial and generalized epilepsy. (d) Seizure types. (e) Seizure frequency during the baseline period. (f) Number of background drugs.

Outcomes

We recorded the number of participants who experienced each outcome (seeTypes of outcome measures) per randomised group, and contacted authors of trials for any missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SR and MP) independently assessed the risk of bias for each trial, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We discussed and resolved disagreements. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study in RevMan (RevMan 2014). We rated all included studies as having a low, high or unclear risk of bias on six domains applicable to randomised controlled trials: randomisation method, allocation concealment, blinding methods, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. We created 'Summary of findings' tables, using GRADEpro and the GRADE approach for assessing the quality of evidence (GRADEpro 2014)

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the primary outcome of seizure reduction as a binary outcome and presented it as a risk ratio. We also analysed secondary outcomes, including treatment withdrawal and adverse effects as binary outcomes and presented risk ratio. We had also planned to present cognitive effects and quality of life as continuous outcomes via mean differences if the same measurement scales were used or via standardised mean differences if different measurement scales were used to measure the same outcome. However, due to the limited amount of data available for these outcomes, we have presented these outcomes in a narrative discussion

Unit of analysis issues

We included eight cross‐over studies in the review. We analysed data from these studies from the first treatment period only; we analysed parallel and cross‐over design studies in separate subgroups.

Dealing with missing data

We sought missing data by contacting the study authors. We carried out intention‐to‐treat (ITT), best case and worst case analysis on the primary outcome to account for any missing data (see Data synthesis). We presented all analyses in the main report.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing the distribution of important participant factors between trials (e.g. age, seizure type, duration of epilepsy, number of antiepileptic drugs taken at time of randomisation), and trial factors (e.g. randomisation concealment, blinding, losses to follow up). We examined statistical heterogeneity using a Chi² test and I² statistic. When we found no significant heterogeneity (P < 0.10), we used a fixed‐effect model. Had we found heterogeneity (> 50%), we had planned to use a random‐effects model for the analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We requested protocols for all included studies to enable a comparison of outcomes of interest. If outcome reporting bias was suspected for any included study, we had planned to further investigate using the ORBIT matrix system (Kirkham 2010). We had planned an examination of asymmetry funnel plots to establish publication bias, but such an assessment was not possible due to the small number of studies included in the review.

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis to synthesise the data. We measured the effect of each comparison on our preset primary and secondary outcomes, if data were available. Comparisons we expected to carry out included:

usual treatment plus lamotrigine versus usual treatment plus placebo

usual treatment plus lamotrigine versus no treatment

usual treatment plus lamotrigine versus usual treatment

Our preferred estimator for all binary outcomes was the Mantel‐Haenzsel Risk Ratio (RR). For the outcomes 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency and treatment withdrawal, we used 95% confidence intervals (Cls). For individual adverse effects we used 99% Cls to make an allowance for multiple testing. Our analyses included all participants in the treatment groups to which they had been allocated following randomisation.

For the efficacy outcome (50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency) we undertook three analyses:

(a) Primary (intention‐to‐treat) analysis Participants not completing follow‐up or with inadequate seizure data were assumed to be non‐responders. To test the effect of this assumption, we undertook the following sensitivity analyses. Analysis by ITT was done where this was reported by the included studies.

(b) Worst case analysis Participants not completing follow‐up or with inadequate seizure data were assumed to be non‐responders in the lamotrigine group, and responders in the placebo group.

(c) Best case analysis Participants not completing follow‐up or with inadequate seizure data were assumed to be responders in the lamotrigine group, and non‐responders in the placebo group.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered adults and children and doses in our subgroup analyses. We performed a subgroup analysis for adverse events.

Sensitivity analysis

We had intended to carry out sensitivity analyses if peculiarities were found between study quality, characteristics of participants, interventions and outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

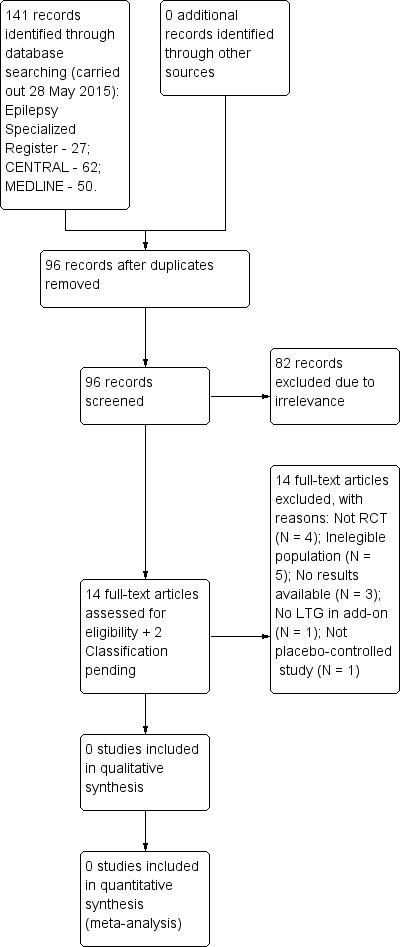

The latest search (carried out 28 May 2015) identified 141 records from the databases outlined above. We screened 96 records after duplicates were removed for inclusion in the review. We excluded 82 at this point, and requested 14 full‐text articles to assess for eligibility. We contacted authors of these trials for more information, providing their contact details were available. Following this, we excluded all 14 studies (please see Figure 1 and Characteristics of excluded studies for reason of exclusion). Thus, no new studies were included in this review.

1.

Study flow diagram for update.

Included studies

We did not find any new studies for this update.

In the previous version of this review, the authors included 14 randomised controlled trials that investigated the use of add‐on lamotrigine compared to placebo, in 1958 participants with uncontrolled partial seizures (38 infants, 199 children, and 1721 adults). Trial characteristics are summarised below. For further information on each trial, please see Characteristics of included studies.

The 14 studies included five parallel group studies (Baulac 2010; Duchowny 1999; Matsuo 1993; Naritoku 2007; Schachter 1995); one parallel group study in infants with a responder‐enriched design, in which all patients received adjunctive lamotrigine during an open‐label phase and those who had a 40% or greater reduction in the frequency of partial seizures during the last four weeks were randomly assigned to double‐blind treatment for up to eight weeks with continued lamotrigine or placebo (Piña‐Garza 2008); and eight cross‐over studies (Binnie 1989; Boas 1996; Jawad 1989; Loiseau 1990; Messenheimer 1994; Schapel 1993; Schmidt 1993; Smith 1993). All the studies but two recruited adults; Duchowny 1999 recruited only children, and Piña‐Garza 2008 enrolled only infants aged one to 24 months of age. One trial used extended‐release formulation of lamotrigine (Naritoku 2007), while the others used immediate‐release formulations. In general, the individuals included in these studies had at least three to four partial seizures a month, despite therapy with a stable AED regime consisting of two or three AEDs, which were appropriate for the type of epilepsy, and were given in adequate doses.

Almost all studies excluded people with: intellectual disabilities, progressive neurological disease, major psychiatric problems, associated pseudo seizures, newly‐diagnosed epilepsy, status epilepticus in the 24 weeks preceding the trial, associated systemic diseases, abnormal laboratory investigations not explained by enzyme induction by AEDs, a history of non‐compliance, failure to keep reliable records of seizures or adverse effects, irregular clinic visits, recent use of any other investigational AED, abuse of alcohol or other prescription or non‐prescription drugs; people receiving chronic medication, especially antipsychotic drugs, women who were pregnant or at risk of pregnancy, lactating women. For the cross‐over studies, participants were not randomised to a single dose, but took a range of doses, depending on their clinical response and the concurrent administration of other AEDs. Use of valproate was not permitted in three studies (Matsuo 1993; Messenheimer 1994; Schachter 1995), two excluded people on valproate monotherapy (Schapel 1993; Smith 1993), while others used lower dosages of lamotrigine for people on valproate. One parallel study tested doses of 300 mg and 500 mg of lamotrigine per day (Matsuo 1993), whereas the others tested a range of doses between 75 mg and 600 mg per day (median between 200 mg and 400 mg/day). The length of the treatment period varied from eight to 24 weeks.

All studies were published as full articles, except Schmidt 1993, which was only published as an abstract. All studies, except Baulac 2010 (which was sponsored by Pfizer Inc), were sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, manufacturers of lamotrigine, as part of their pre‐licensing programme.

Excluded studies

In this update, we excluded 14 studies for the following reasons: four studies were not randomised trials; five studies did not study an eligible population; study results were not available for three studies; one study did not include LTG as part of the add‐on therapy; and one study was not a placebo‐controlled trial. The details of these studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

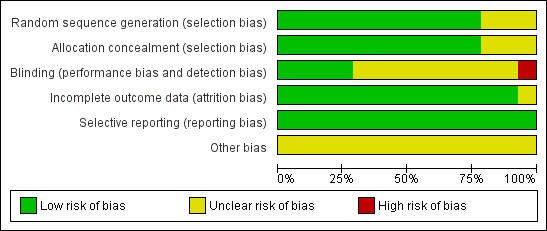

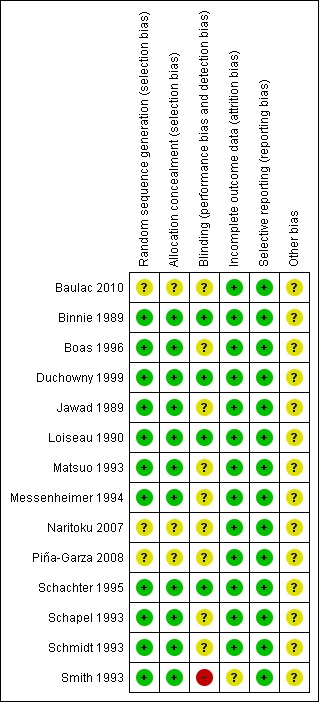

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of the risk of bias in each included study. Each study was allocated an overall rating for risk of bias: low, high, or unclear. See below for specific domain ratings.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We rated the method by which allocation was randomised as having a low risk of bias in eleven trials (n = 1243 participants), because they used a computer‐generated randomisation schedule or random number tables (Binnie 1989; Boas 1996; Duchowny 1999; Jawad 1989; Loiseau 1990; Matsuo 1993; Messenheimer 1994; Schachter 1995; Schapel 1993; Schmidt 1993; Smith 1993). The investigators did not provide clear methods In three trials (n = 715 participants), which were rated as unclear (Baulac 2010; Naritoku 2007; Piña‐Garza 2008). For sequence generation, we rated the same 11 studies as having a low risk of bias because they dispensed sequentially numbered packages to each participant, and random permuted blocks were used to generate the allocation sequence. We rated three studies (n = 715 participants) as unclear due to a lack of details on the methods used (Baulac 2010; Naritoku 2007; Piña‐Garza 2008).

Blinding

We rated three studies (n = 504 participants) as having a low risk of bias for this particular domain because participants, parents and investigators were blinded (Binnie 1989; Jawad 1989; Schachter 1995). We judged blinding of participants as unclear in ten papers (n = 1373 participants) because no details of the method of blinding were provided (Baulac 2010; Boas 1996; Duchowny 1999; Loiseau 1990; Matsuo 1993; Messenheimer 1994; Naritoku 2007; Piña‐Garza 2008; Schapel 1993; Schmidt 1993). One study (n = 81 participants) was rated as high risk of bias because patients and investigators were able to identify the lamotrigine treatment (Smith 1993).

Incomplete outcome data

We rated all the included studies, except one (Smith 1993) (n = 1877 participants), as having a low risk of bias for this domain as minimal missing data were reported; either intention‐to‐treat analysis was employed, or there were no concerns of missing data having an effect on the overall outcome estimate. Smith 1993 was rated as unclear risk of bias because participants who discontinued prematurely did not complete the HRQOL measure at the time of discontinuation.

Selective reporting

We requested the protocols for all included studies to compare a priori methods and outcomes to the published report, but none of the protocols for the included studies were available. We rated all included studies as low risk of bias for this domain as there was no suspicion of selective outcome reporting bias. All expected outcomes were reported in each of the publications.

Other potential sources of bias

All these studies, except one (Baulac 2010, which was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.), were sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufacturers of the LTG, and therefore, we rated all but one study as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

For the cross‐over trials, we analysed data from the first treatment phase for the efficacy, treatment, withdrawal, and adverse effects. These data were unpublished and obtained from Glaxo Wellcome, the sponsors of all but one study (Baulac 2010).

Primary Outcome

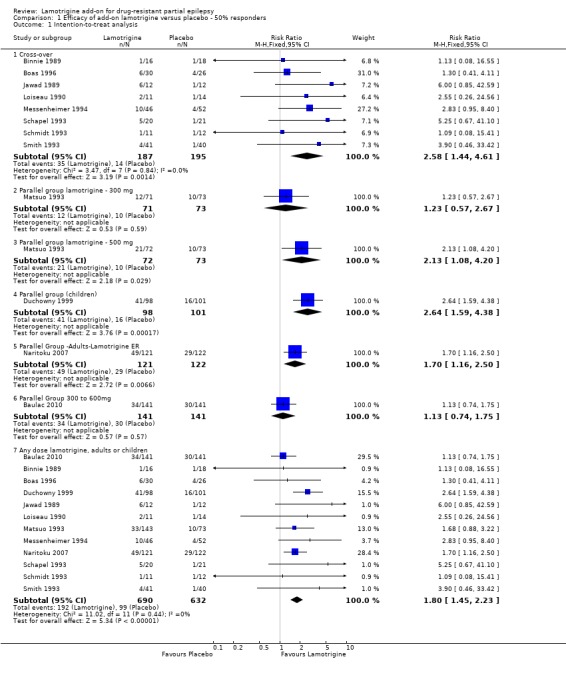

Greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency

A Chi² test for responses to lamotrigine indicated no significant heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 11.02; df = 11; P = 0.44; I² = 0%), so a fixed‐effect model was used to measure efficacy.

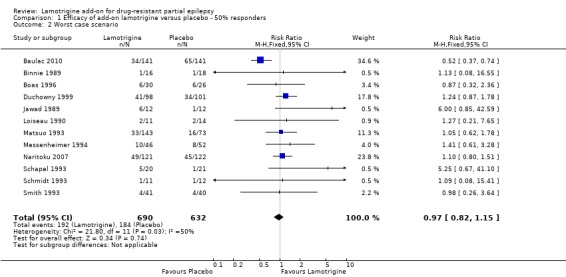

For twelve studies (n = 1322 participants, adults and children), the RR was 1.80; 95% CI 1.45 to 2.23 for any dose of lamotrigine added to regular anti‐epileptic drug therapy versus placebo. The RR from eight cross‐over studies (N = 382 participants) was 2.58; 95% CI 1.44 to 4.61 (Analysis 1.1).The RR for the best case and worst case scenarios were RR 2.88 (95% CI 2.36 to 3.50) and RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.15) respectively (Analysis 1.2, Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Efficacy of add‐on lamotrigine versus placebo ‐ 50% responders, Outcome 1 Intention‐to‐treat analysis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Efficacy of add‐on lamotrigine versus placebo ‐ 50% responders, Outcome 2 Worst case scenario.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Efficacy of add‐on lamotrigine versus placebo ‐ 50% responders, Outcome 3 Best case scenario.

The RR for a daily dose of 300 mg of lamotrigine was 1.23; 95% CI 0.57 to 2.67; the RR was 2.13; 95% CI 1.08 to 4.20 for lamotrigine 500 mg per day, compared to placebo (Matsuo 1993). For children, the RR was 2.64; 95% CI 1.59 to 4.38 (Duchowny 1999).

We could not calculate responder rates for Schachter 1995 because baseline seizure counts were not obtained, or for the infants in Piña‐Garza 2008, where the primary end point was exit due to treatment failure,

Secondary Outcomes

Treatment withdrawal

Fourteen studies (n = 1958 participants) were included in this analysis. The overall RR for treatment withdrawal for any reason was (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.36); thus there was insufficient evidence to conclude that participants were more likely to discontinue lamotrigine than placebo (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Treatment withdrawal (global outcome), Outcome 1 Withdrawal from treatment.

We obtained the following data: 186 participants withdrew from treatment and 77 participants withdrew from control groups in parallel studies in adults (Baulac 2010, Matsuo 1993, Naritoku 2007, Schachter 1995); 14 participants withdrew from treatment and 18 from control groups in a parallel study in children (Duchowny 1999); 19 participants withdrew from treatment and 10 participants withdrew from control groups in cross‐over studies in adults (Binnie 1989, Boas 1996, Jawad 1989, Loiseau 1990, Messenheimer 1994, Schapel 1993, Schmidt 1993, Smith 1993); 11 participants withdrew from treatment and 16 withdrew from control groups in a parallel study in infants (Piña‐Garza 2008).

Insufficient data were available to undertake the planned dose‐response subgroup analyses.

Adverse effects

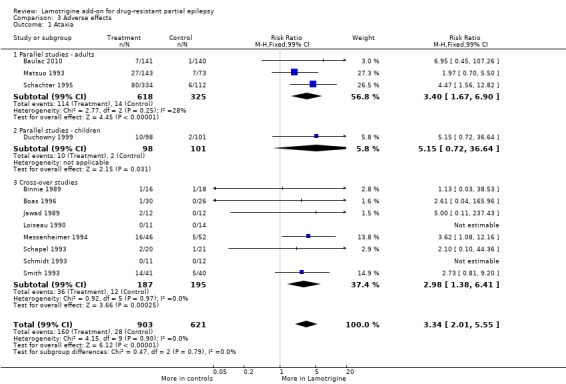

In addition to reports of ataxia, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea, some studies reported somnolence, diplopia and headache among the five most common adverse effects and are included in the analysis. Ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, and nausea were significantly more likely with lamotrigine. The RR for individual adverse effects were:

ataxia ‐ RR 3.34; (99% CI 2.01 to 5.55) (12 studies, 1524 participants, Analysis 3.1);

dizziness ‐ RR 2.00 (99% CI 1.51 to 2.64) (13 studies, 1767 participants, Analysis 3.2);

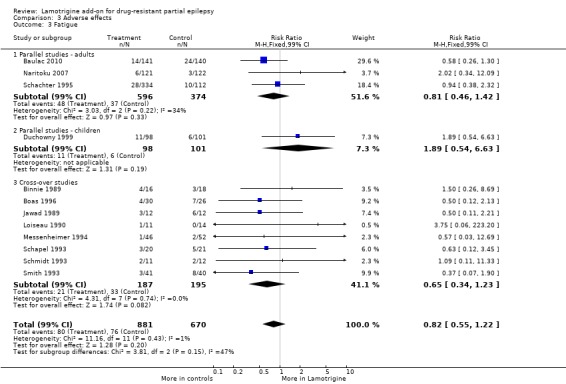

fatigue ‐ RR 0.82 (99% CI 0.55 to 1.22) (12 studies, 1551 participants, Analysis 3.3);

nausea ‐ RR 1.81(99% CI 1.22 to 2.68) (12 studies, 1486 participants, Analysis 3.4);

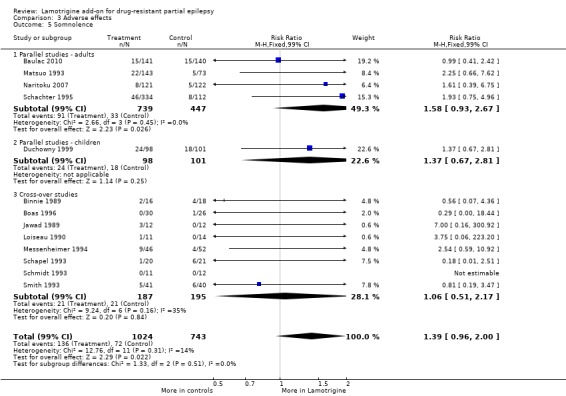

somnolence ‐ RR 1.39 (99% CI 0.96 to 2.00) (13 studies, 1767 participants, Analysis 3.5);

diplopia ‐ RR 3.79 (99% CI 2.15 to 6.68) (3 studies, 943 participants, Analysis 3.6); and

headache ‐ RR 1.13 (99% CI 0.87 to 1.45) (5 studies, 1385 participants, Analysis 3.7).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 1 Ataxia.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 2 Dizziness.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 3 Fatigue.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 4 Nausea.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 5 Somnolence.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 6 Diplopia.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adverse effects, Outcome 7 Headache.

Cognitive effects and Quality of life

Two studies incorporated measures of cognitive functions (Banks 1991; Smith 1993; n = 54 participants). No significant differences were found on any of the tests used. However, participants receiving lamotrigine showed a marginal (not significant) reduction in general cerebral efficiency as assessed by the third segment of the Stroop colour word test‐a test of concentration and distractibility (Table 5).

1. Cognitive outcomes.

| Outcome | Study | Number tested | Lamotrigine mean | Placebo mean |

| Stroop time | Smith 1993 | 41 | 93.98 | 98.39 |

| Stroop error | Smith 1993 | 44 | 2.18 | 2.41 |

| Stroop colour word (Total score) | Banks 1991 | 10 | 32.4+/‐10.9 | 35.6+/‐9.42 |

| Number cancellation: AC | Smith 1993 | 44 | 51.36 | 49.7 |

| Number cancellation: AE | Smith 1993 | 43 | 3.6 | 3.04 |

| Number cancellation: BC | Smith 1993 | 42 | 48.21 | 48.54 |

| Number cancellation: C | Smith 1993 | 42 | 38.19 | 39.29 |

| Critical flicker fusion | Smith 1993 | 40 | 30.44 | 30.37 |

| Choice reaction time | Smith 1993 | 40 | 0.675 | 0.669 |

| Digit symbol (Scaled score) | Banks 1991 | 10 | 5 +/‐2.45 | 6.6 +/‐ 2.71 |

| Rey complex figure recall percentile | Banks 1991 | 10 | 22+/‐17.51 | 30.5+/‐27.33 |

| Trail making part B percentile | Banks 1991 | 10 | 26+/‐30.35 | 30.5+/‐32.09 |

We provided a narrative discussion for this outcome and more information in Table 5. Meta‐analysis of the two studies was not possible due to the differences in cognitive function measured in the two studies.

The results of the health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) assessments are given in Table 6. Smith 1993 (n = 54 participants), incorporated an HRQOL measure containing previously validated measures of physical, social and psychological functioning and a novel measure of seizure severity. There were no significant differences for the physical and social components of the HRQOL measure. Participants also reported significant improvements on the seizure severity scale when comparing lamotrigine versus placebo.

2. Health related quality of life outcomes (Smith 1993).

| Outcome | Number tested | Lamotrigine ‐ Mean | Placebo ‐ Mean | Clinical relevance |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL: | ||||

| Depression | 54 | 4.24 | 4.26 | No significant difference |

| Happiness | 51 | 3.8 | 1.96 | Higher scores in LTG group; P = 0.003 |

| Mood | 50 | 24.36 | 26.8 | No significant difference |

| Self‐esteem | 50 | 30.06 | 29.16 | No significant difference |

| Mastery | 50 | 20.02 | 18.78 | Higher scores in LTG group; P = 0.003 |

| Anxiety | 54 | 6.87 | 6.83 | No significant difference |

| PHYSICAL (Nottingham Health Profile): | ||||

| Energy | 53 | 0.68 | 0.68 | No significant difference |

| Pain | 53 | 0.6 | 0.69 | No significant difference |

| Emotional reaction | 53 | 1.96 | 1.96 | No significant difference |

| Sleep | 53 | 0.89 | 0.76 | No significant difference |

| Social isolation | 53 | 0.92 | 0.94 | No significant difference |

| Physical mobility | 53 | 0.96 | 0.91 | No significant difference |

| SEIZURE SEVERITY SCALE: | ||||

| Percept | 53 | 25.19 | 25.47 | No significant difference |

| Ictal | 53 | 19.47 | 20.53 | Less severe seizures in LTG group; P = 0.017 |

| Caregivers | 53 | 20.35 | 21.80 | Less severe seizures in LTG group; P = 0.035 |

We provided a narrative discussion for this outcome and more information in Table 6. Meta‐analysis was not possible as only a single study reported on this outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Since publication of the previous version of this review, we found no new studies that met the selection criteria for this review.

The baseline phase in all but one trial ranged from 4 to 12 weeks, the treatment phase from 8 to 36 weeks (Schmidt 1993). Eleven of the fourteen included trials described adequate methods of concealment of randomisation, only four described adequate blinding. All but one trial was sponsored by the manufacturer of lamotrigine.

This meta‐analysis suggested that lamotrigine was more effective than placebo in reducing seizure frequency, when added to conventionally used antiepileptic drugs in people suffering from refractory partial epilepsy. We were unable to examine dose effects in planned subgroup analyses, but the results from Matsuo 1993 suggested increased efficacy with an increased dose. Only one study recruited children (Duchowny 1999), and one study recruited infants (Piña‐Garza 2008); we have no evidence from this review to indicate whether lamotrigine is more or less effective in infants and children than in adults. The use of 50% or more reduction in seizure frequency as a measure of efficacy could be criticized, given that seizure freedom would be a more relevant clinical measure. However, seizure freedom was rarely achieved in the studies involving people with refractory epilepsy.

For a drug to be an attractive option, it would need to have a favourable adverse effect profile, have little effect on cognition, and have positive effects on quality of life, in addition to reducing seizures. In our review, certain adverse effects (ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, and nausea) were significantly more likely to occur with lamotrigine. It was emphasized that researchers should routinely and regularly enquire about adverse effects, using a standardised check‐list thesaurus, and should not record only those volunteered by the patient. More participants had lamotrigine withdrawn than placebo, but this was not statistically significant.

The results of this review apply only to add‐on use of lamotrigine. Our results do not inform us how add‐on lamotrigine compares with other drugs when used as add‐ons, which is an extremely important issue for clinicians who are faced with an ever increasing number of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) from which to choose, and who need to make an evidence‐based choice between the AEDs. Indirect comparisons can be made using results of other reviews, but such indirect comparisons require cautious interpretation.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only two studies evaluated the effects of add‐on lamotrigine therapy on cognition and quality of life. The results of these studies suggested that lamotrigine was probably not associated with any significant cognitive decline. Anyway, the limited data available and heterogenous measurement scales for quality of life outcome precluded us from drawing any conclusions about the effects on cognition and quality of life.

Caution is required when translating the results of clinical trials into everyday practice, since the individuals in trials are a highly selected population who may be better motivated, and are closely followed and monitored; participants who are uncooperative and non‐compliant, who are likely to have adverse effects and fewer benefits, are excluded. The results of this review cannot be extrapolated to people with generalized epilepsies, about whom there is a great paucity of data. The safety of lamotrigine during pregnancy and lactation cannot be ascertained from this review. The duration of the studies included in this review was insufficient to detect changes in cognition, social problems, or long‐term adverse effects. Trials that include a larger number of individuals, preferably who are using lamotrigine as monotherapy, and which are using reliable, validated measures and longer follow‐up are warranted. This review did not have the sensitivity to detect rare but serious adverse effects, such as psychosis, Steven Johnson's syndrome, or aplastic anaemia which may be seen with AEDs. Rare phenomena such as habituation and tolerance may not be evident in short‐term trials. The economic aspects of lamotrigine therapy also need to be examined.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, eleven studies were rated as having low risk of bias and three had an unclear risk of bias, due to lack of reported information around study design. Effective blinding of studies of lamotrigine was only reported in three studies. We rated all the included studies as low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data due to the intention‐to‐treat analyses undertaken by the study authors. The GRADE approach was used to rate the quality of evidence for each outcome and is presented in a 'Summary of findings' table (see Table 1). For the main outcome of greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, the quality of evidence was rated as high (all studies contributed to the analysis). Tolerability outcomes (withdrawal and adverse effects) were judged as high to moderate quality due to the incomplete outcome data from some studies contributing to the analysis and a wide confidence intervals.

Potential biases in the review process

Although all protocols were requested, the time frame in which the majority of the studies were conducted made retrieval of all of these difficult. This could lead to potential bias through omitted information to which we did not have access. All studies but one were sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufacturers of lamotrigine and this could be a potential source of bias.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In people with drug‐resistant partial epilepsy, lamotrigine when used as an add‐on treatment was effective in reducing the seizure frequency. The lowest daily dose tested in the trials included in this review was 75 mg for people on sodium valproate monotherapy, 100 mg in the balanced group receiving enzyme inducing AEDs and valproate, and 200 mg in people receiving enzyme inducing AEDs. However, the trials reviewed were of relatively short duration.

Implications for research.

Further evaluation of lamotrigine is required to assess the following effects in the long term:

effects on seizures;

adverse effects;

effects on cognition;

effects on quality of life;

health economic effects.

In the following scenarios:

lamotrigine compared to other add‐on treatments in drug‐resistant partial epilepsy;

lamotrigine for childhood and generalized epilepsies;

-

lamotrigine compared with standard AEDs such as:

lamotrigine as monotherapy in partial epilepsy;

lamotrigine as monotherapy in generalized epilepsy.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 April 2017 | Amended | Declarations of interest section updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 May 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 28 May 2015. No new relevant studies were identified. |

| 28 May 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 6 January 2010 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 6th January 2010. Two new studies have been included (Naritoku 2007 and Piña‐Garza 2008); the conclusions are unchanged. |

| 10 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 April 2007 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 25th April 2007. One new conference abstract (Carignani 2006) has been added to the 'Studies Awaiting Classification' section. This will be assessed for inclusion at a later date. |

| 16 November 2005 | Amended | We re‐ran our search on 31 March 2005. One new study (Carignani 2004) has been added to the 'studies awaiting assessment' section. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Professor Gus Baker for his contribution to the original publication of this review.

GlaxoSmithKline provided unpublished data for the first treatment phase of cross‐over trials.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register search strategy

#1 (lamotrigine OR lamictal) AND >2011:YR

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 lamotrigine or lamictal

#2 (epilep* or seizure* or convulsion*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#3 MeSH descriptor: [Epilepsy] explode all trees

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Seizures] explode all trees

#5 (#2 or #3 or #4) in Trials

#6 #1 and #5 from 2012

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

This strategy is based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials (Lefebvre 2011).

1. (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or (randomi?ed or placebo or randomly).ab.

2. clinical trials as topic.sh.

3. trial.ti.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

6. 4 not 5

7. exp Epilepsy/

8. exp Seizures/

9. (epilep$ or seizure$ or convuls$).tw.

10. 7 or 8 or 9

11. (lamotrigine or lamictal).ti,ab.

12. 6 and 10 and 11

13. limit 12 to ed=20120701‐20150528

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Efficacy of add‐on lamotrigine versus placebo ‐ 50% responders.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intention‐to‐treat analysis | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Cross‐over | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.58 [1.44, 4.61] |

| 1.2 Parallel group lamotrigine ‐ 300 mg | 1 | 144 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.57, 2.67] |

| 1.3 Parallel group lamotrigine ‐ 500 mg | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [1.08, 4.20] |

| 1.4 Parallel group (children) | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.64 [1.59, 4.38] |

| 1.5 Parallel Group ‐Adults‐Lamotrigine ER | 1 | 243 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [1.16, 2.50] |

| 1.6 Parallel Group 300 to 600mg | 1 | 282 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.74, 1.75] |

| 1.7 Any dose lamotrigine, adults or children | 12 | 1322 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.80 [1.45, 2.23] |

| 2 Worst case scenario | 12 | 1322 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.82, 1.15] |

| 3 Best case scenario | 12 | 1322 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [2.36, 3.50] |

Comparison 2. Treatment withdrawal (global outcome).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Withdrawal from treatment | 14 | 1805 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.90, 1.36] |

| 1.1 Parallel studies ‐ adults | 4 | 1186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.90, 1.50] |

| 1.2 Parallel studies in children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.42, 1.52] |

| 1.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.89, 3.72] |

| 1.4 Parallel Studies in Infants | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.45, 1.06] |

Comparison 3. Adverse effects.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ataxia | 12 | 1524 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 3.34 [2.01, 5.55] |

| 1.1 Parallel studies ‐ adults | 3 | 943 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 3.40 [1.67, 6.90] |

| 1.2 Parallel studies ‐ children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 5.15 [0.72, 36.64] |

| 1.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 2.98 [1.38, 6.41] |

| 2 Dizziness | 13 | 1767 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 2.00 [1.51, 2.64] |

| 2.1 Parallel studies ‐ adults | 4 | 1186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 2.09 [1.49, 2.94] |

| 2.2 Parallel studies ‐ children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 4.33 [1.27, 14.79] |

| 2.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.41 [0.83, 2.38] |

| 3 Fatigue | 12 | 1551 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 0.82 [0.55, 1.22] |

| 3.1 Parallel studies ‐ adults | 3 | 970 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 0.81 [0.46, 1.42] |

| 3.2 Parallel studies ‐ children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.89 [0.54, 6.63] |

| 3.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 0.65 [0.34, 1.23] |

| 4 Nausea | 12 | 1486 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.81 [1.22, 2.68] |

| 4.1 Parallel Studies ‐ adults | 3 | 905 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.68 [1.02, 2.78] |

| 4.2 Parallel studies ‐ children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 5.67 [0.81, 39.69] |

| 4.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.67 [0.85, 3.29] |

| 5 Somnolence | 13 | 1767 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.39 [0.96, 2.00] |

| 5.1 Parallel studies ‐ adults | 4 | 1186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.58 [0.93, 2.67] |

| 5.2 Parallel studies ‐ children | 1 | 199 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.37 [0.67, 2.81] |

| 5.3 Cross‐over studies | 8 | 382 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.06 [0.51, 2.17] |

| 6 Diplopia | 3 | 943 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 3.79 [2.15, 6.68] |

| 7 Headache | 5 | 1385 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 99% CI) | 1.13 [0.87, 1.45] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baulac 2010.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomised, parallel‐group study. Three arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine, and 1 pregabalin. Baseline period = 6 weeks; double‐blind treatment period = 17 weeks, which included initial 5 weeks dosage titration for lamotrigine and 6 weeks maintenance at 300 mg/day and additional treatment period of 6 weeks with dose escalation to 400 mg/day for those with continuing seizures. Double‐blind treatment period was followed by an open‐label study or a 2‐week taper phase. |

|

| Participants |

Exclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Group I (n = 141): received placebo. Group II (n = 141): received lamotrigine 300 mg/day after dose titration over 5 weeks, and if seizures occurred during 6‐week maintenance, further dose escalation to 400 mg/day from week 12 to 17. Group III (n = 152): received pregabalin. |

|

| Outcomes | (1) Seizure frequency. (2) Adverse events, including changes in physical and neurologic examinations, 12‐lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), and clinical laboratory tests (hematology, blood chemistry, pregnancy, and urinalysis). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The details were not mentioned in the publication. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details provided regarding blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors. Regarding the medications, blinding was maintained by administering the same numbers of capsules per day per group. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 35 withdrew from placebo group and 40 from lamotrigine group. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol unavailable to check a priori outcomes, but appears all expected and pre‐specified outcomes are reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Responder rates were mentioned as percentages and actual numbers were not given. Author has been contacted regarding actual number of responders in each group. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. |

Binnie 1989.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, and 1 lamotrigine. Baseline period = 8 weeks.Treatment I and II = 12 weeks each. Washout = 6 weeks, including taper period. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine, or placebo. Median daily dose of lamotrigine was 200 mg. Participants on valproate received lower doses. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were allocated sequentially‐numbered sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and parents were blinded. An unblinded investigator with knowledge of the medication and plasma concentrations instructed the blinded investigators about dispensing the trial medications. Identical tablets and packaging used. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. No participant withdrew from the study during the first treatment phase. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check to priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Boas 1996.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Five phases: baseline period = 12 weeks; treatment I = 12 weeks; washout I = 4 weeks; treatment II = 12 weeks; washout II = 4 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Lamotrigine or placebo was added to the patients' existing AEDs. The dose of lamotrigine varied from 75 to 400 mg. Participants on valproate received lower doses. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Partcipants were allocated sequentially‐numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details provided regarding blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors. All treatments (tablets) and packaging were identical. Prepacked coded medication was dispensed by pharmacy. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 10 participants withdrew from the study; 8 randomised to lamotrigine and 2 to placebo. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Duchowny 1999.

| Methods | Randomized, double blind, parallel group, multi‐centre study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Pre‐randomization baseline period = 8 weeks. Treatment phase = 18 weeks (including 6‐week titration). Taper and follow‐up = 1 to 6 weeks, including 1‐week taper. | |

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. Median dose ranged from 2.7 to 12.9 mg/kg/day depending upon concurrent use of other AEDs. Participants on valproate received lower doses. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients were randomised with a blocked randomisation scheme to treatment with add‐on lamotrigine or matched placebo in bottles labelled with pre‐generated participant numbers. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment assignments were unknown to all study‐site personnel, patients and sponsors. Lamotrigine and matching placebo were provided as berry‐flavoured, chewable, dispersible caplets or tablets in strengths of 5, 25, and 100 mg. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 2 enrolled participants withdrew before randomisation. 14 participants allocated to lamotrigine and 18 participants allocated to placebo withdrew during treatment phase. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Jawad 1989.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Five phases: baseline period = 8 weeks; Treatment I = 12 weeks; Washout I = 6 weeks; treatment II = 12 weeks; Washout II = 6 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. The median daily dose of lamotrigine was 250 mg. Participants on valproate received lower doses. Unblinded investigator wrote prescriptions based on plasma concentration. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Partcipants were allocated by sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details provided regarding blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors. Identical tablets and packaging used. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. One participant who was allocated to lamotrigine withdrew from the study (the reason for exclusion was reported) and none withdrew from the placebo group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Loiseau 1990.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Five phases: Pre‐randomisation baseline = 4 weeks. Treatment I = 8 weeks. Washout I = 4 weeks. Treatment II = 8 weeks. Washout II = 4 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. The median daily lamotrigine dose was 300 mg. Participants on valproate received lower doses. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were allocated by sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Neurologists, participants and parents were blinded. Investigators were blinded. All treatments (tablets) and packaging were identical. Pre‐packed coded medication dispensed by pharmacy. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 2 participants withdrew from the study; 1 receiving lamotrigine and 1 receiving placebo. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Matsuo 1993.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, parallel group, multi‐centre study.

Three treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine 300 mg and 1 lamotrigine 500 mg. Pre‐randomisation baseline = 12 weeks. Treatment phase = 24 weeks. Taper and follow‐up = 3 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine 300 mg or lamotrigine 500 mg or placebo. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation concealment: allocated sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details provided regarding blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors. Identical tablets and packaging used. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 25 participants withdrew from the study; 7 receiving lamotrigine 300 mg, 12 receiving lamotrigine 500 mg and 6 receiving placebo. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol unavailable to check a priori outcomes, but appears all expected and pre‐specified outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Messenheimer 1994.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Total study duration was 43 weeks. Pre‐randomisation baseline = 8 weeks. Treatment A = 14 weeks (including 2 weeks blinded tapering). Follow‐up period = 3 weeks. Treatment B = 14 weeks (including 2 weeks blinded tapering). Washout = 4 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. Median lamotrigine dose 400 mg/day. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were allocated by sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Investigators were blinded. No more information provided regarding blinding of neurologists, participants, and parents. All treatments (tablets) and packaging were identical. Pre‐packed coded medication dispensed by pharmacy. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 6 participants withdrew from the study; 2 receiving lamotrigine and 4 receiving placebo. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Naritoku 2007.

| Methods | Double‐blind, randomised, parallel‐group, placebo‐controlled multi‐centre global study. Screening phase of up to 2 weeks during which eligibility was determined; an 8‐week baseline phase serving to exclude from randomisation patients who did not meet the minimum seizure frequency criterion; a 7‐week, double‐blind escalation phase during which lamotrigine XR (Extended Release) was introduced and titrated to its target dose; and a 12‐week, double‐blind maintenance phase during which dosage of study medication and concomitant AED were maintained. |

|

| Participants |

Exclusion criteria included: presence of primary generalized seizures, status epilepticus during or within 24 weeks before the start of the baseline phase, chronic treatment with three or more AEDs, current or previous use of lamotrigine, current use of felbamate or adherence to a ketogenic diet, and pregnancy or planned pregnancy during the study or within 3 weeks after the last dose of study medication. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment group received lamotrigine XR (Extended Release); other group received identical placebo. Dosage of lamotrigine XR was escalated gradually up to 200 mg/day in those receiving valproate, 300 mg/day in those receiving valproate and an enzyme inducing AED, and up to 500 mg/day in those receiving enzyme inducing AEDs without valproate. |

|

| Outcomes | (1) Seizure frequency. (2) Adverse events (3) Withdrawals from study. US subjects had following additional assessments: Profile of Mood States (POMS), Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression Scale (CES‐D), research version of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory‐Epilepsy (NDDI‐E), Quality of Life in Epilepsy‐31‐P (QOLIE‐31‐P), Liverpool Adverse Experience Profile (AEP), Seizure Severity Questionnaire (SSQ), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported in the publication. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 24 subjects withdrew from treatment group and 16 from placebo group. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes,but appears all expected and pre‐specified outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Piña‐Garza 2008.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, multi‐centre placebo‐controlled trial. Responder‐enriched design in which all patients received adjunctive lamotrigine during an open‐label phase (wherein dose was escalated to achieve optimal response); those who had a 40% or greater reduction in the frequency of partial seizures during the last 4 weeks of the optimisation period were randomly assigned to double‐blind treatment for up to 8 weeks with continued lamotrigine or placebo. |

|

| Participants |

Exclusion Criteria: subjects with progressive myoclonic epilepsy; progressive neurologic disease, seizures unrelated to epilepsy or resulting from drug withdrawal; use of felbamate, adrenocorticotropic hormone, previous use of lamotrigine, two AEDs as maintenance treatment, presence of hepatic dysfunction, having a functioning vagus nerve stimulator; or being on a ketogenic diet. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group was continued on lamotrigine. Control group subjects had their lamotrigine dose tapered and changed to placebo. The maximum maintenance dose was 5.1 mg/kg/day for those on non–enzyme‐inducing AEDs or valproate and 15.6 mg/kg/day for those on enzyme‐inducing AEDs. | |

| Outcomes | (1) Percentage of patients who had treatment failures during the double‐blind phase. (2) Cumulative percentage of patients who met escape criteria as a function of days on double‐blind study medication. Subjects were withdrawn from study if they met one of the following criteria:

|

|

| Notes | The protocol was amended midway through the study to randomly assign all patients with at least 40% reduction in seizure frequency, instead of planned inclusion of subjects with 40% to 80% reduction in seizure frequency. 43 subjects who had more than 80% reduction in seizure frequency before the protocol amendment were not included in the double‐blind study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported in the publication. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 11 patients (8 in the lamotrigine group and 3 in placebo group) completed the double‐blind phase, 25 (9 in the lamotrigine group and 16 in placebo group) met escape criteria, and 2 (both in the lamotrigine group) prematurely withdrew because of protocol violations. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected and pre‐specified outcomes were reported. Protocol was not available. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Schachter 1995.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group study.

Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine.

Patients were randomised to lamotrigine or placebo in a ratio of 3:1. Pre‐randomisation baseline = 4 weeks. Treatment phase = 24 weeks. Taper and follow‐up = 3 weeks. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. Lamotrigine dose up to 500 mg/day. | |

| Outcomes | (1) Withdrawals from treatment. (2) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were allocated by sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Neurologists, participants and parents were blinded. Investigators were blinded. Identical tablets and packaging used. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. 73 participants withdrew from the study; 53 receiving lamotrigine and 20 receiving placebo. The reasons for exclusion were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in methods section of paper were reported in the results. There was no protocol available to check a priori outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the manufactures of LTG. |

Schapel 1993.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Two treatment arms: 1 placebo, 1 lamotrigine. Pre‐randomization baseline = 12 weeks. Treatment I and II = 12 weeks each. Washout I and II = 4 weeks each, including 1 week taper. |

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Add‐on lamotrigine or placebo. Median daily dose of lamotrigine was 300 mg. Participants receiving valproate received lower doses. | |

| Outcomes | (1) 50% responder rates. (2) Withdrawal from study for any reason. (3) Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Banks 1991 is linked to this study and investigated cognitive functions (concentration and attention; general cerebral efficiency; mnestic function). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were allocated by sequentially numbered, sealed packages containing either lamotrigine or placebo. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details provided regarding blinding of participants, study personnel, and outcome assessors. All treatments and packaging were identical. Pre‐packed coded medication dispensed by pharmacy. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participants were excluded from analysis. None withdrew from the study. |