Epistasis occurs when the effect of a genetic variant on a trait is dependent on genotypes of other variants elsewhere in the genome. Hemani et al. recently reported the detection and replication of many instances of epistasis between pairs of variants influencing gene expression levels inhumans1. Using whole-genome sequencing data from 450 individuals we strongly replicated many of the reported interactions but, in each case, a singlethird variant captured by our sequencing data could explain all of the apparent epistasis. Our results provide an alternative explanation for the apparent epistasis observed for gene expression in humans. There is a Reply to this Brief Communication Arising by Hemani, G. et al. Nature 514, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature13692 (2014).

Hemani et al.1 identified 30 pairs of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; Table 1 in Hemani et al.1) that interacted to influence the expression of 19 different gene transcripts. These interactions were robust to adjustment for multiple testing and were replicated across two independent studies. Most of the replicated apparently interacting SNP pairs were associated with gene expression in cis and were located close to each other on the same chromosome (all <520 kilobases). We have previously shown that low levels of correlation due to linkage disequilibrium (LD) between variants can cause apparent allelic heterogeneity at an associated locus2. We therefore hypothesized that low levels of LD could explain the epistasis observed by Hemani et al.1.

Table 1 |.

Results from running pairwise SNP interaction analyses on SNP pairs identified and replicated by Hemani et al.1 and the results observed after conditioning on the most strongly associated additive cis variant identified in the InCHIANTI sequencing study (IncSeq)

| SNP pairs from Hemani et al. Table 1 | Two SNPs from Hemani et al. | Adjusted for IncSeq variant | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cis/trans | Gene (chr) | SNP1 (chr) | SNP2 (chr) | IncSeq variant* | 8 d.f. full model P | Interaction P | 8 d.f. full model P | Interaction P |

| Cis | ADK (10) | rs2395095 (10) | rs10824092 (10) | 10:75928933 | 3.2 × 10−19 | 9.1 × 10−04 | 0.99 | 0.86 |

| Cis | ATP13A1 (19) | rs4284750 (19) | rs873870 (19) | 19:19756073 | 2.1 × 10−05 | 7.9 × 10−03 | 0.87 | 0.64 |

| Cis | C210RF57 (21) | rs9978658 (21) | rs11701361 (21) | 21:47703649 | 3.8 × 10−05 | 7.2 × 10−03 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| Cis | CSTB (21) | rs9979356 (21) | rs3761385 (21) | 21:45201832 | 6.2 × 10−07 | 8.3 × 10−07 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Cis | CTSC (11) | rs7930237 (11) | rs556895 (11) | 11:88015717 | 3.5 × 10−15 | 5.0 × 10−06 | 7.0 × 10−08 | 0.04 |

| Cis | FN3KRP (17) | rs898095 (17) | rs9892064 (17) | 17:80678628 | 2.8 × 10−11 | 2.9 × 10−12 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| Cis | GAA (17) | rs11150847 (17) | rs12602462 (17) | 17:78096086 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| Cis | HNRPH1 (5) | rs6894268 (5) | rs4700810 (5) | 5:178978883 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| Cis | LAX1 (1) | rs1891432 (1) | rs10900520 (1) | 1:203747772 | 8.3 × 10−08 | 1.6 × 10−04 | 0.27 | 0.52 |

| Cis | MBNL1 (3) | rs16864367 (3) | rs13079208 (3) | 3:152182577 | 1.1 × 10−07 | 2.7 × 10−06 | 0.41 | 0.16 |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs7710738 (5) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | 3.1 × 10−05 | 2.3 × 10−02 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs2030926 (6) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | 2.2 × 10−05 | 3.2 × 10−02 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs2614467 (14) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | 3.7 × 10−04 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.55 |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs218671 (17) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | 1.4 × 10−03 | 0.90 | 0.38 | 0.79 |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs11981513 (7) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | 1.6 × 10−05 | 1.6 × 10−02 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Cis | MBP (18) | rs8092433 (18) | rs4890876 (18) | 18:74723459 | 1.2 × 10−02 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.28 |

| Cis | NAPRT1 (8) | rs2123758 (8) | rs3889129 (8) | 8:144684215 | 6.8 × 10−34 | 6.2 × 10−06 | 0.40 | 0.84 |

| Cis | NCL (2) | rs7563453 (2) | rs4973397 (2) | 2:232320581 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.85 | 0.71 |

| Cis | PRMT2 (21) | rs2839372 (21) | rs11701058 (21) | 21:47887791 | 2.6 × 10−15 | 2.6 × 10−04 | 0.52 | 0.30 |

| Cis | SN0RD14A (11) | rs2634462 (11) | rs6486334 (11) | 11:17230389 | 1.7 × 10−05 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.17 |

| Cis | TMEM149 (19) | rs807491 (19) | rs7254601 (19) | 19:36234489 | 3.0 × 10−31 | 2.9 × 10−06 | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs6926382 (6) | 19:36234489 | 3.2 × 10−43 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.53 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs914940 (1) | 19:36234489 | 3.7 × 10−42 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.71 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs2351458 (4) | 19:36234489 | 3.5 × 10−42 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.46 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs6718480 (2) | 19:36234489 | 6.1 × 10−42 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.69 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rsl843357 (8) | 19:36234489 | 4.0 × 10−41 | 0.44 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs9509428 (13) | 19:36234489 | 3.3 × 10−42 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.39 |

| Cis | VASP (19) | rs1264226 (19) | rs2276470 (19) | 19:46033382 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.56 |

Data was available for 28 of the 30 interactions reported by Hemani et al.1. Both the full model and interaction associations for the Hemani et al. SNPs are completely removed on adjustment for the additive effect of our single most associated variant.

IncSeq variant is the most strongly associated additive variant with probe levels in cis (± 1Mb probe start site).

To address this hypothesis, we used a combination of whole-genome sequence data and whole-blood gene expression traits in 450 individuals from the InCHIANTI study2. Gene expression levels were measured using a similar Illumina array (Human HT-12 v3.0) as Hemani et al.1 used for all of their discovery and replication analyses and we used the same analysis software (epiGPU3).

We first replicated the apparent interactions detected and replicated by Hemani et al. (11 of 17 cis–cis pairs and 3 of 11 cis–trans pairs with P<0.05; Table 1). Our lower success rate of replicating the cis–trans effects is consistent with their reported smaller effect sizes. Wecould not analyse two of the gene expression traits because either the probe or one of the SNPs failed quality control in our study. We next identified the single most strongly associated variant for each of the 17 gene expression traits from our whole-genome sequencing analysis. For 27 out of 28 SNP pairs the individual variant most strongly associated with gene expression in our data was more strongly associated than the 8 degrees of freedom (8 d.f.) fullmodel formed from the pair of SNPsreported in Hemani et al. (Table 1). For all 17 putatively interacting pairs where both SNPs occurred onthe samechromosome our more strongly associated variant was moderately correlated with both of the interacting SNPs (Table 2). These correlations occurred despite very low levels of LD between the two SNPs described by Hemani et al.

Table 2 |.

Linkage disequilibrium measures between SNP pairs identified by Hemani et al.1 and the most strongly associated cis variant identified in the InCHIANTI sequencing study

| SNP pairs from Hemani et al. Table 1 | Linkage disequilibrium between variants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cis/trans | Gene (chr) | SNP1 (chr) | SNP2 (chr) | IncSeq variant* | SNPl-SNP2 r2/D′ | SNP1 - IncSeq r2/D′ | SNP2 - IncSeq r2/D′ | |

| Cis | ADK (10) | rs2395095 (10) | rs10824092 (10) | 10:75928933 | 0/0.01 | 0.39/0.81 | 0.1/1 | |

| Cis | ATP13A1 (19) | rs4284750 (19) | rs873870 (19) | 19:19756073 | 0.01/0.11 | 0.07/0.9 | 0.04/0.82 | |

| Cis | C210RF57 (21) | rs9978658 (21) | rs11701361 (21) | 21:47703649 | 0.02/0.19 | 0.02/0.2 | 0.02/0.21 | |

| Cis | CSTB (21) | rs9979356 (21) | rs3761385 (21) | 21:45201832 | 0.04/0.23 | 0.05/0.25 | 0.14/0.38 | |

| Cis | CTSC (11) | rs7930237 (11) | rs556895 (11) | 11:88015717 | 0/0.07 | 0.22/0.9 | 0.11/0.94 | |

| Cis | FN3KRP (17) | rs898095 (17) | rs9892064 (17) | 17:80678628 | 0/0.04 | 0.01/0.12 | 0.05/0.27 | |

| Cis | GAA (17) | rs11150847 (17) | rs12602462 (17) | 17:78096086 | 0.01/0 | 0.3/1 | 0.11/0.94 | |

| Cis | HNRPH1 (5) | rs6894268 (5) | rs4700810 (5) | 5:178978883 | 0.02/0.23 | 0.05/0.42 | 0.3/0.63 | |

| Cis | LAX1 (1) | rs1891432 (1) | rs10900520 (1) | 1:203747772 | 0.03/0.23 | 0.21/0.51 | 0.05/0.29 | |

| Cis | MBNL1 (3) | rs16864367 (3) | rs13079208 (3) | 3:152182577 | 0.08/0.42 | 0.13/0.62 | 0.06/1 | |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs7710738 (5) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | NA | NA | 0.44/1 | |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs2030926 (6) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | NA | NA | 0.44/1 | |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs2614467 (14) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | NA | NA | 0.44/1 | |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs218671 (17) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | NA | NA | 0.44/1 | |

| Trans | MBNL1 (3) | rs11981513 (7) | rs13069559 (3) | 3:152182577 | NA | NA | 0.44/1 | |

| Cis | MBP (18) | rs8092433 (18) | rs4890876 (18) | 18:74723459 | 0.04/0.22 | 0.11/0.43 | 0.21/0.62 | |

| Cis | NAPRT1 (8) | rs2123758 (8) | rs3889129 (8) | 8:144684215 | 0.03/0.17 | 0.4/0.96 | 0.06/0.68 | |

| Cis | NCL (2) | rs7563453 (2) | rs4973397 (2) | 2:232320581 | 0.04/0.25 | 0.29/0.83 | 0.16/0.76 | |

| Cis | PRMT2 (21) | rs2839372 (21) | rs11701058 (21) | 21:47887791 | 0.07/0.28 | 0.01/0.11 | 0.33/0.95 | |

| Cis | SNORD14A (11) | rs2634462 (11) | rs6486334 (11) | 11:17230389 | 0/0 | 0.07/0.62 | 0.04/0.59 | |

| Cis | TMEM149 (19) | rs807491 (19) | rs7254601 (19) | 19:36234489 | 0/0.11 | 0.11/0.93 | 0.51/0.9 | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs6926382 (6) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs914940 (1) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs2351458 (4) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs6718480 (2) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs1843357 (8) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Trans | TMEM149 (19) | rs8106959 (19) | rs9509428 (13) | 19:36234489 | NA | 0.84/0.99 | NA | |

| Cis | VASP (19) | rs1264226 (19) | rs2276470 (19) | 19:46033382 | 0.01/0.12 | 0.05/0.47 | 0.1/0.57 | |

NA, not applicable because the SNPs are on different chromosomes.

IncSeq variant is the most strongly associated additive variant with probe levels in cis (± 1Mb probe start site).

We next re-evaluated the evidence for interaction but this time corrected for the presence of our most strongly associated variant. The inclusion of our third variant removed any evidence for interaction (Table 1). This included the removal of apparently strong interactions involving cis variants for MBNL1 and TMEM149 (also known as IGFLR1), the two transcripts that account for all of the cis–trans interactions. Additionally, the most strongly associated variant for MBNL1 occurs in the probe sequence used to detect expression of the gene, raising the possibility of a technical explanation for the cis–trans interactions. Our results mean that the apparent epistasis reported by Hemani et al. is more likely to be due to moderate levels of LD between each of the two SNPs and a single causal allele rather than genuine epistasis.

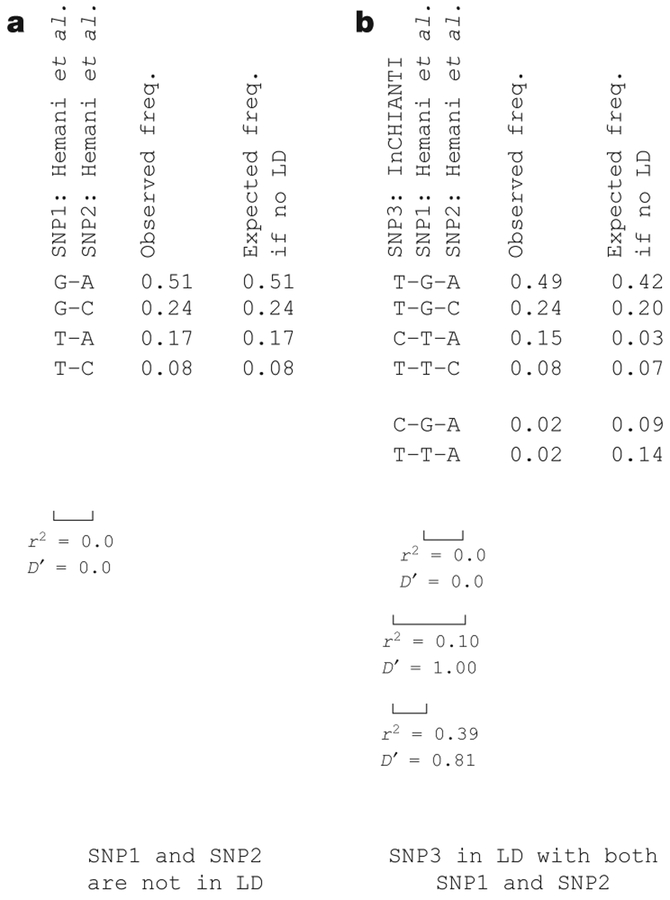

Hemani et al. attempted to remove interaction effects driven by low levels of correlation with additive variants by removing pairs of SNPs with pairwise r2 <0.1 and D’2 <0.1 (Table 2). However, it is possible to have substantial multi-locus LD but no pairwise LD4. Fig. 1 provides an example of the haplotype structure for the ADK locus, where there is no LD between the twointeracting SNPs, but the most associated variant from our study has moderate LD with both of the SNPs.

Figure 1 |. Haplotype and linkage disequilibrium structure.

a, b, Haplotype and LD structure are shown at the ADK locus of two proposed epistatic SNPs from Hemani et al.1 (a) and when adding a third SNP captured by sequencing in 450 Italian individuals (b). The two “epistatic” SNPs form all four of the possible haplotypes. When adding the third SNP no new haplotypes are formed at >.2.4% frequency. Haplotypes were estimated using Haploview8.

In summary, using whole-genome sequencing and independent data, we have provided an alternative explanation for the findings of Hemani et al.1 and conclude that there remain few robust examples of epistasis in humans.

Methods

Gene expressionprofileswere captured usinganIllumina HumanHT-12 v3.0Bead-Chip array2. Whole-genome sequencing was performed at the Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China) using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (median read depth 7×). Reads were processed using GATK5 before genotype recovery and refinement through within-sample imputation using BEAGLE6. Analysis of the 8 d.f. model and interaction term was performed using epiGPU3. To determine whether the observed interactions were driven by unaccounted for additive variants, we obtained the most strongly associated variant in cis (1 megabase ± probe start site) using MACH2QTL7, generated a phenotype of residuals for each expression trait by regressing out the variant, and then repeated the epiGPU analysis using the adjusted trait.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests Declared none.

References

- 1.Hemani G et al. Detection and replication of epistasis influencing transcription humans. Nature 508, 249–253 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Wood AR et al. Allelic heterogeneity and more detailed analyses of known loci explain additional phenotypic variation and reveal complex patterns of association. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 4082–4092 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemani G, Theocharidis A, Wei W & Haley C EpiGPU: exhaustive pairwise epistasis scans parallelized on consumer level graphics cards. Bioinformatics 27, 1462–1465 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen DM, Ehm MG, Zaykin DV & Weir BS Effect of two- and three-locus linkage disequilibrium on the power to detect marker/phenotype associations. Genetics 168, 1029–1040 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DePristo MA et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browning BL & Yu Z Simultaneous genotype calling and haplotype phasing improves genotype accuracy and reduces false-positive associations for genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet 85, 847–861 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P & Abecasis GR MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet. Epidemiol 34, 816–834 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J & Daly MJ Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21, 263–265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]